Abstract

Researchers have examined perceived discrimination as a risk factor for depression among sexual minorities; however, the role of religion as a protective factor is under-investigated, especially among sexual minority youth. Drawing on a cross-sectional study investigating campus climate at a large public university in the U.S. midwest, we examined the role of affiliation with a gay-affirming denomination (i.e., endorsing same-sex marriage) as a moderating factor in the discrimination–depression relationship among self-identified sexual minority (n = 393) and heterosexual youth (n = 1,727). Using multivariate linear regression analysis, religious affiliation was found to moderate the discrimination–depression relationship among sexual minorities. Specifically, the results indicated that the harmful effects of discrimination among sexual minority youth affiliated with denominations that endorsed same-sex marriage were significantly less than those among peers who affiliated with denominations opposing same-sex marriage or who identified as secular. In contrast, religious affiliation with gay-affirming denominations did not moderate the discrimination–depression relationship among heterosexual participants. The findings suggest that, although religion and same-sex sexuality are often seen as incompatible topics, it is important when working with sexual minority clients for clinicians to assess religious affiliation, as it could be either a risk or a protective factor, depending on the religious group’s stance toward same-sex sexuality. To promote the well-being of sexual minority youth affiliated with denominations opposed to same-sex marriage, the results suggest these faith communities may be encouraged to reconsider their position and/or identify ways to foster youth’s resilience to interpersonal discrimination.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Studies demonstrate significantly higher rates of depression among sexual minorities compared with their heterosexual counterparts (Bolton & Sareen, 2011; Espelage et al., 2008; Loosier & Dittus, 2010; Marshal et al., 2011; Rivers & Noret, 2008; Williams & Chapman, 2011; Williams et al., 2005). Given the relationship of depression with other negative health outcomes, including substance use (Swendsen and Merikangas, 2000), non-suicidal self-injury (Hilt et al., 2008; Walls et al., 2010), and suicide (Eisenberg et al., 2007), it is critical to understand the covariates of depression, especially among high-risk groups.

Minority stress theory posits that, among sexual minorities, mental health problems develop, in part, due to stigma and a hostile social environment (Meyer, 2003). In regard to the social environment, studies have found that interpersonal discrimination is a risk factor for depression among sexual minorities (Mays & Cochran, 2001; Meyer, 1995, 2003), including sexual minority youth (D’Augelli et al., 2005; D’Augelli et al. 2002; Espelage et al., 2008; Woodford, Han, Craig, Lim, & Matney, 2014; Woodford, Krentzman, & Gattis, 2012a). Although any person can experience discrimination, discrimination is often higher among sexual minorities compared with heterosexuals (Kralovec et al., 2012; Silverschanz et al., 2008; Woodford et al., 2012a, 2014). A recent national study conducted with college students documented greater rates of interpersonal discrimination, ranging from being the target of derogatory remarks to being a victim of physical violence, among sexual minority participants compared with their heterosexual counterparts (Rankin, Weber, Blumenfeld, & Frazer, 2010).

To develop effective mental health interventions for sexual minority youth, we must understand protective factors that might moderate risk factors in addition to examining risk factors (Anderson, 1998; Fenaughty & Harre, 2003; Fraser, Galinsky, & Richman, 1999; Grossman & Kerner, 1998; Russell, 2005; Saewyc et al., 2009; Wright & Perry, 2006). Various facets of religion, including affiliation, can be protective factors for mental health and psychological well-being among the general population and specific sub-groups (Ellison, Finch, Ryan, & Salinas, 2009; Gartner, Larson, & Allen, 1991; George, Ellison, & Larson, 2002; McCullough & Larson, 1999; Smith, McCullough, & Poll, 2003), including college students (Abdel-Khalek & Naceur, 2007). However, the role of religion as a protective factor among sexual minority individuals is less clear (Rostosky, Danner, & Riggle, 2007; Wright & Perry, 2006), particularly when there is conflict between one’s religious faith and sexual identity (Hamblin & Gross, 2014).

Religion can play a mixed role in the lives of sexual minorities, especially when anti-gay religious messages are promoted (Ganzevoort, van der Laan, & Olsman, 2011; Harris, Cook, & Kashubeck-West, 2008; Levy, 2012; Schuck & Liddle, 2001) and reparative therapy (a pseudo-scientific treatment that attempts to change sexual orientation from homosexual to heterosexual) is endorsed (Grace, 2008). Recent studies found that religious affiliation was associated with better mental health among sexual minority adults, but also with more internalized homophobia, which is known to be associated with mental health problems (Kralovec et al., 2012; Newcomb & Mustanski, 2010; Walker & Longmire-Avital, 2013).

Illustrating the complexity of religion for sexual minorities, Kralovec et al. (2012) found that, among a sample of gay, lesbian, and bisexual adults, being in a religious denomination was associated with more general social support, but with less sexual orientation-specific social support. Also among sexual minority adults, having religious experiences that affirm their sexual identity (e.g., religious doctrine that supports sexual minorities, faith communities that specifically serve sexual minorities) has been found to promote psychological health (Lease, Horne, & Noffsinger-Frazier, 2005). Research is needed on the role of religious affiliation as it relates specifically to the link between perceived interpersonal discrimination and depression among sexual minorities.

Most studies that have examined the intersection of psychological distress and religion have been conducted with sexual minority adults, yet youth and adults are often at different stages of sexual development (Boxer & Cohler, 1989) and religious identity (Fowler, 1981). Concerning the latter, youth generally are at a stage of critical reflection and exploration, whereas adults tend to be much further along (Fowler, 1981; Woodford, Levy, & Walls, 2013). These differences highlight the importance of studying the potential protective role of religious affiliation among youth. Further, given the evolving nature of (some) religious denominations’ doctrine on same-sex sexuality (see Pew Research Center, 2012; Woodford, Walls, & Levy, 2012b), it is timely to investigate the role of denominational stance on recognition of same-sex relationships.

Using a risk and protective factor framework in understanding depressive symptoms among sexual minority youth, we examined the role of religious affiliation as a protective factor on the relationship between perceived interpersonal discrimination and depression. Because religious doctrine concerning same-sex sexuality is likely an important factor, we explored the role of belonging to a denomination that endorsed same-sex marriage, opposed same-sex marriage, or had an undefined position. We used denominational stance on same-sex marriage as an indicator of affirmation of sexual minorities and categorized denominational affiliation into these three groups because of the ongoing public controversy about the legal recognition of same-sex relationships and the often public role that denominations play in contemporary policy debates (e.g., California Catholic Conference, 2008; Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints, 2008; Jones, 2012; Woodford et al., 2012b). Further, studies show that many young people abandon organized religion as part of their faith development (Arnett, 2000; Smith & Snell, 2009). Because identifying as secular (i.e., not affiliating with a religion or not having religious beliefs) has been shown to be a protective factor against internalized homophobia, which research suggests is positively associated with depression among sexual minorities (Rowen & Malcolm, 2002), we also included secular individuals in our sample. Unlike other studies investigating the intersection of religion, depression, and sexuality, we included a heterosexual comparison group.

To advance understanding of the potential unique contribution of religious affiliation as a potential protective factor for the discrimination-depression relationship, we asked: Does religious affiliation moderate the effects of interpersonal discrimination on depressive symptoms among sexual minority youth and heterosexual youth? Among sexual minority youth, we hypothesized that affiliation with a religious denomination would be a protective factor in the discrimination–depression relationship, but only if the denomination was affirming of sexual minority relationships (e.g., endorsing same-sex marriage). In particular, we expected to observe a smaller discrimination–depression relationship among sexual minority youth affiliated with denominations that endorsed same-sex marriage, relative to youth affiliated with religious denominations that opposed same-sex marriage (Hypothesis 1). We anticipated finding a similar pattern when comparing sexual minority youth who belonged to denominations that supported same-sex marriage with those affiliated with denominations that had an undefined position on the topic (Hypothesis 2) or who identified as secular (Hypothesis 3). Among heterosexual youth, we hypothesized that membership in a gay-affirming denomination would have no effect on a link between discrimination and depression (Hypothesis 4).

Method

Participants

The sample (n = 2,120) consisted of 393 sexual minority and 1,727 heterosexual participants. Table 1 provides a demographic profile of the sexual minority and heterosexual samples. Most participants in both samples were female and, on average, 23 years of age. The sexual minority sample consisted of 12 % completely gay/lesbian, 8 % mostly gay/lesbian, 17 % bisexual, and 63 % mostly heterosexual.

Procedure

Data were drawn from a cross-sectional study investigating campus climate at a large, public, research university located in the U.S. Midwest. Campus climate was defined on the informed consent form as “the actions and attitudes within a university that influence whether people feel welcomed and valued as members of the community.” An advisory committee consisting of students, alumni, staff, and faculty assisted with the study. The study received institutional review board approval. Data were collected using an anonymous online survey. Both full- and part-time students who were at least 18 years of age were eligible to participate in the study. Recruitment consisted of a census of sophomore and junior undergraduate students, a random sample of graduate students, and a convenience sample of sexual minority students involved in lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) student organizations. Participants had the opportunity to enter their name for a drawing for one of fifty $50 cash cards. Sexuality or LGBT issues were not mentioned in the recruitment materials.

Individuals in the census (N = 11,342) and random samples (N = 8,000) were contacted and invited to participate in the study by using official university email addresses. Reminder messages were sent 7 and 14 days later. The invitation and reminder messages included the survey link. The web-based survey system indicated that 5,006 students opened the survey link, and 3,762 students agreed to participate in the study. However, 1,194 students were omitted due to no data or partial data, thus resulting in a dataset of 2,568 for the original census and random sample. The response rate based on number of students invited was 13 %; the response rate based on number of students known to have received the invitation was 51 %.

To actively recruit sexual minority students involved in LGBT organizations, an invitation to join the study was posted on the list serve for leaders of LGBT student organizations and the leaders were asked to forward the message to their organizations’ members. Reminder messages were posted 7 and 14 days later for distribution to organizational members. The survey link was included in the invitation and reminder messages. Students were asked to complete the survey if they had not previously been invited to do so. Of the 73 students who agreed to join the study, only 37 surveys contained sufficient data to be included in the original convenience sample.

Combining the 2,568 participants in the census/random sample and the 37 participants in the convenience sample, the original study sample included 2,605 students. As discussed below, students were excluded from the study who selected “other Christian,” “other non-Christian,” or “not listed (please specify)” for current religion, “not listed (please specify)” for sex, or “not listed (please specify)” for sexual orientation, as were participants with missing data on study variables, resulting in an analytic sample of 2,120 students (373 sexual minorities and 1,727 heterosexuals from the census/random sample; 20 sexual minorities from the convenience sample).

Measures

We measured sexual orientation using an updated version of Kinsey, Pomeroy, and Martin’s (1948) homosexual-heterosexual rating scale (category labels were updated to reflect language commonly used by college students): “What is your sexual orientation?” (“completely lesbian or gay,” “mostly lesbian or gay,” “bisexual,” “mostly heterosexual,” and “completely heterosexual”). We also included the category “not listed (please specify),” but as noted, this group was excluded from analysis because of very small group size. Consistent with previous studies (Chakraborty, McManus, Brugha, Bebbington, & King, 2011; Silverschanz, Cortina, Konik, & Magley, 2008; Ueno, 2010), we considered the “mostly heterosexual” group to be a sexual minority because these participants were self-identifying as a minority regarding sexual attraction, identity, and/or behavior, and not part of the “completely heterosexual” majority group.

Dependent Variable

Depressive symptoms were measured using the Depression sub-scale from the Brief Symptom Inventory (Derogatis, 1975). Participants’ scores were calculated based on a composite of six items (e.g., loss of interest, loneliness, suicidal ideation) that used a 5-point Likert scale (0 = not at all, 4 = extremely) to assess one’s level of depressive symptoms during the past 7 days. Similar to its use in other studies (Heck et al. 2011; Mustanski et al. 2011), the scale had strong internal reliability with our sample (sexual minorities α = .87; heterosexuals α = .86).

Independent Variables

To identify the role of affiliation with a denomination affirming same-sex sexuality in the perceived discrimination–depressive symptoms relationship, we examined two primary independent variables. The first variable, affiliation with a denomination affirming same-sex sexuality, was operationalized as a denomination’s official position on same-sex marriage. In our survey, we asked students to select their current religious affiliation from a list of 22 options. This list was taken from the Cooperative Institutional Research Program’s Freshman Survey, which is administered throughout the U.S. (Higher Education Research Institute, 2008). We grouped denominations by official position on same-sex marriage in accordance with the categorization developed by the Pew Research Center (2012). We grouped denominations as endorsing same-sex marriage if they were described as supporting same-sex marriage (e.g., “bless,” “legally recognize and advocate,” “approve”) or as opposing same-sex marriage if they were described as objecting to these relationships (e.g., “oppose,” “law forbid,” “not sanction”). We classified as “undefined” denominations not described as having a position or a mixed position on same-sex marriage. Participants who selected “agnostic,” “atheist,” or “none” were categorized as secular. Those who selected “other Christian,” “other non-Christian,” or “not listed” were excluded from the analysis due to an inability to categorize their stance on same-sex marriage. For analysis, we developed a four-category variable (endorsed same-sex marriage, opposed same-sex marriage, undefined position on same-sex marriage, and secular) for religious affiliation. The denominations constituting each category are listed in the footnotes for Table 1.

Perceived interpersonal discrimination was the second independent variable. We measured this variable based on 13 items that represent experiences of hostility (e.g., physical threats), incivility (e.g., staring, sneering, or dirty looks), and heterosexist harassment (e.g., homophobic name-calling) in the past 12 months on campus. Each of the items was originally scored using a 4-point scale (0 = never, 4 = 10-plus times); sexual minorities α = .81; heterosexuals α = .71. This scale was developed with input from the study advisory committee and student affairs staff. A large proportion of students in each group reported never experiencing any discrimination (sexual minority, 44 %; heterosexual, 62 %); therefore, we dichotomized this variable into “no reported incident” versus “at least one reported incident” (0/1) as done in previous research (Silverschanz et al., 2008).

Control Variables

Control variables consisted of demographic characteristics that have been found in previous studies to relate to one’s psychological adjustment, namely age, sex, and race (Kessler et al., 2005). We assessed sex through the question, “What is your sex?”: original response categories were “male,” “female,” and “not listed.” Those who selected “not listed” were excluded due to inadequate group size. Students selected from a list of eight options (including “not listed”) for race. We dichotomized race into people of color/White because of the low number of racial minorities, especially in the sexual minority sample. We also controlled for religiosity, specifically, the importance of religion in one’s life, because despite mixed findings on the role of religiosity concerning the well-being of sexual minority youth (Eliason, Burke, van Olphen, & Howell, 2011; Rostosky et al., 2007; Wright & Perry, 2006), the degree to which one considers religion an important part of one’s life is generally regarded as a protective factor (George et al., 2002). Participants who selected a religious affiliation were asked to specify how important religion was to them (1 = not at all important, 4 = very important); we coded secular individuals as 1. Finally, in the model conducted with sexual minorities, we controlled for sexual orientation, namely, mostly heterosexual versus lesbian/gay or bisexual.

Data Analysis

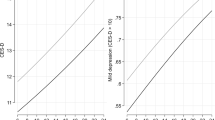

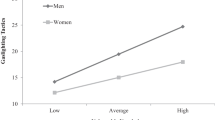

We conducted descriptive statistics for all study variables for sexual minority youth and heterosexual youth. To identify any significant differences between the two groups, we conducted t-tests for continuous variables and Chi square tests for dichotomous variables. To test the hypotheses, multivariate linear regression analysis was performed for each group. As a baseline assessment of the relationship between discrimination, religious affiliation, and depression, Model 1 included perceived interpersonal discrimination, religious affiliation, and the control variables. To examine the protective effects of religious affiliation, Model 2 assessed the main and moderating effects of religious affiliation. We created interaction terms for perceived interpersonal discrimination and religious affiliation. Given our interest in the role of affiliation with a same-sex affirming religion, we used endorsing same-sex marriage as the reference category. Finally, we provided a graphical representation for the results of the multivariate linear regression analysis based on the sexual minority youth and heterosexual youth samples. We plotted the results for the interaction between perceived interpersonal discrimination and religious affiliation based on coefficients estimated from Model 2. In detail, the two graphs—representing sexual minority youth (see Fig. 1) and heterosexual youth (see Fig. 2)—were based on predicted values of depressive symptoms scores for each group of interest (e.g., secular, endorsed same-sex marriage, opposed same-sex marriage, and undefined position on same-sex marriage), while keeping other covariates at their respective mean values.

Results

Descriptive Findings

A descriptive summary of the study variables by sexual orientation is reported in Table 1. The depression score was significantly greater among sexual minority youth compared with heterosexual youth. Also, a greater proportion of sexual minority youth reported experiencing perceived interpersonal discrimination in the past 12 months on campus than did heterosexual youth. Regarding religious affiliation, a greater proportion of heterosexual youth reported being affiliated with denominations that either endorsed same-sex marriage or opposed same-sex marriage whereas more sexual minorities identified as secular. With regard to controls, compared with sexual minority youth, religiosity was significantly higher among heterosexual youth, and a significantly lower percentage of heterosexual participants were female. No significant differences were found for the remaining variables.

Explanatory Findings

Table 2 shows the results of the multivariate linear regression analysis conducted with each group.

Sexual Minority Youth

In the baseline assessment (Model 1), perceived interpersonal discrimination was significantly and positively associated with depression scores; religious affiliation, namely, affiliation with a denomination opposing same-sex marriage versus affiliation with one endorsing same-sex marriage, was positively associated with depression scores at the trend level. Further, religiosity was significantly and negatively associated with depression scores. Model 1 explained 10.0 % of the variance in the dependent variable, F(9, 383) = 5.65, p < .001.

In Model 2, religious affiliation significantly moderated the discrimination–depression relationship among sexual minority youth (see Fig. 1). Specifically, those belonging to denominations opposed to same-sex marriage and those identifying as secular had a significantly greater increase in depressive symptoms scores compared with those affiliated with a denomination that endorsed same-sex marriage. Religiosity maintained statistical significance in this model. The addition of the interaction items accounted for 1.4 % of the explained variance, F(3, 380) = 2.72, p = .04.

Heterosexual Youth

In the baseline model (Model 1), perceived interpersonal discrimination was significantly and positively associated with the dependent variable, as was being female. Race and religiosity were significantly and negatively related to depression scores among these students. This model accounted for 5.1 % of the explained variance in the dependent variable, F(8, 1718) = 11.4, p < .001. In Model 2, none of the interaction terms achieved statistical significance (see Fig. 2). The variables found to be significant in the baseline model remained significant in Model 2. The addition of interaction items increased the explained variance by 0.1 %, F(3,1715), p = .77.

Discussion

This study advanced the understanding of the relationship between sexuality, interpersonal discrimination, depression, and religion among youth. The results suggested that, among sexual minority youth, those belonging to a denomination that was gay affirming may have served as a protective factor for the discrimination–depression relationship compared with those affiliated with a denomination opposed to same-sex sexuality and to secular youth. In contrast, religious affiliation had no significant effect for heterosexual youth.

Understanding the role of religion among youth in general is important given that emerging and young adulthood represent critical periods in religious identity development, including establishing one’s own religious beliefs (Fowler, 1981). It is especially so among sexual minority youth, who are developing their sexual identity in a predominantly heterosexual world (Dahl & Galliher, 2009; Garcia, Gray-Stanley, & Ramirez-Valles, 2008). Research has shown that religion can provide social support and may buffer the harmful effects of everyday stressors on individuals’ mental health and well-being (Lease et al., 2005). Given the complicated and sometimes-perceived incompatible nature of religion and a sexual minority identity (Dahl & Galliher, 2010; Finlay & Walther, 2003; Levy, 2012), some may be inclined to dismiss religion as a potential protective factor against the negative psychological distress effects of discrimination. Although evidence suggests that being religiously affiliated can promote psychological health among sexual-minority emerging adults and adults (Kralovec et al., 2012; Walker & Longmire-Avital, 2013), our study highlighted the importance of denominational stance on same-sex relationships, rather than religious affiliation alone, as a protective factor in the association between perceived interpersonal discrimination and depressive symptoms among sexual minority youth.

The main effects indicated that, compared with sexual minority youth affiliated with denominations opposing same-sex marriage, participants who were affiliated with denominations supporting same-sex marriage reported fewer depressive symptoms (significant at the level of a trend, p = .05). However, in terms of religious affiliation acting as a protective factor, the interaction effects indicated that religious affiliation moderated the association between perceived interpersonal discrimination and depressive symptoms. Specifically, consistent with our predictions, being part of a denomination that affirmed same-sex marriage may have protected sexual minority youth against the harmful effect of perceived interpersonal discrimination on depressive symptoms, compared with belonging to one that opposed same-sex marriage (Hypothesis 1) or identifying as secular (Hypothesis 3).

These results provided evidence that belonging to a denomination that affirms same-sex marriage–not just any religious group–may have a “buffering effect” (Wheaton, 1985) against the potential negative psychological consequences of discrimination. It is possible that membership in a gay-affirming denomination exposed sexual minority youth to positive messages about same-sex sexuality and/or provided them with social support and other resources that were helpful in overcoming interpersonal stressors, such as interpersonal discrimination, whereas such positive factors may not have been available to youth affiliated with anti-gay denominations or to secular youth. It is also possible that sexual minorities who were members of affirming denominations or who sought more affirming and supportive environments generally were more confident in their sexual identity compared with the other two groups, and religious affiliation may not have been the driving factor. Additional research is needed to examine these potential explanations.

The findings concerning secular sexual minority participants were intriguing given research suggesting that being secular is a protective factor for internalized homophobia (Rowen & Malcolm, 2002), which is positively related to mental health problems (Meyer, 1995). Many youth become skeptical of institutionalized religion and question religious beliefs developed during their earlier years, and some youth grow to identify as non-religious or agnostic (Arnett, 2000; Fowler, 1981; Smith & Snell, 2009). For sexual minority youth, some may leave their religion due to possible conflicts between their denomination’s teaching and their sexuality, which may contribute to accepting their minority sexual identity (Levy, 2012). The results suggested that compared with sexual minority youth affiliated with gay-affirming religious denominations, secular youth may have less protection against the potential negative effects of discrimination in terms of depressive symptoms. In addition to lack of the social support and other resources that membership in a gay-affirming denomination may offer, the negative dynamics of secular sexual minority youth’s past affiliations, if any, may contribute to the increased moderated risk for depression. Future research is needed, including examining religious upbringing and the rationale for leaving one’s denomination, if that is the case.

Compared with sexual minority youth who were members of religious denominations that endorsed same-sex relationships, there was no statistically significant difference for youth affiliated with the undefined group, in terms of main effects or interaction terms (contrary to Hypothesis 3). These results, however, should be interpreted with caution, given that the undefined category was operationalized to include denominations with a mixed position or no position, which makes it difficult to provide substantive meaning to this set of results in relation to sexual minority youth in the same-sex endorsing group. As posited, the results indicated that, for heterosexual youth, membership in a gay-affirming denomination did not significantly impact the relationship between discrimination and depression (Hypothesis 4).

Implications

Although this was a relatively healthy sample in terms of reported depressive symptoms, our results offer important clinical and policy implications. The results indicated that, when working with sexual minority youth, it is important for clinicians to assess religious affiliation, as it could be functioning either as a risk or a protective factor depending on affiliation and stance toward same-sex marriage. Clinicians who are not competent in exploring topics related to religion may wish to consult pastoral counselors and/or seek additional education. Many youth may be affiliated with a specific religion because of their family; thus, by inquiring about religious affiliation, family dynamics regarding the youth’s minority sexual status may also be identified and, in some cases, religious doctrine may be quite influential in such dynamics. For sexual minority youth who have no religious affiliation or those belonging to denominations opposing same-sex marriage, it may be important for clinicians to offer particular support, including developing healthy coping mechanisms. For secular sexual-minority youth, that support may be for existential issues that may be driving higher mental health risks (Longo, Walls, & Wisneski, 2012), while for those belonging to non-affirming denominations it may be more focused on integrating religious and sexual identities. Among the latter group, it may benefit youth to help them understand the alternative interpretations of anti-gay scripture (Goss & West, 2000) or to seek out support from gay-affirming members of their faith communities. It will also be important for clinicians to help sexual minority youth from both groups to identify other resources that may foster resilience to discrimination.

This study also offers policy implications. The results suggest that gay-equality organizations committed to addressing LGB health disparities may want to engage the leaders and members of denominations opposing same-sex marriage about their stance on the topic. Although policy change is often slow, especially in religious institutions, recent history shows that LGB-inclusive policy change is possible (see Woodford et al., 2013). Intergroup dialogue may be an effective way to engage these stakeholders. This methodology aims to foster intergroup awareness, understanding, and action concerning privilege/oppression (Dessel, Woodford, & Warren, 2011). Further, given the pivotal role of religious leaders within faith communities, strategies targeting these stakeholders are needed. Identifying pro-gay religious leaders and encouraging them to engage their colleagues and congregation members in reflection and dialogue about religious teachings against same-sex marriage and their implications for sexual minority youth, may create a momentum for policy change (see The National Gay and Lesbian Taskforce’s Institute for Welcoming Resources for helpful materials; http://www.welcomingresources.org/). Given that such change will not be immediate, it will be important for allies within these religious institutions to develop ways to support sexual minority youth as well.

Limitations and Future Research

This study had numerous methodological strengths (e.g., use of an anonymous online survey to collect sensitive information, inclusion of secular youth, inclusion of a heterosexual comparison group); however, limitations also existed. Alongside the limitations associated with cross-sectional studies, survey research, and self-reported data, we were unable to determine the sample’s representativeness because the host institution did not record information about students’ sexual orientation. The response rate for the original sample was low (though consistent with the response rate for campus-wide student learning and satisfaction surveys conducted at the host university), and the use of a convenience sample prohibited generalizing the findings to the host institution or to college student samples in general. Also, our measure of interpersonal discrimination included items addressing general mistreatment and mistreatment based on sexual orientation. Although research shows that general discrimination is greater among sexual minorities compared with heterosexuals (Rankin et al., 2010; Woodford et al., 2012a), it remains unclear what kind of discrimination was experienced and which forms of discrimination were impacted by religious affiliation. Furthermore, the role of religious affiliation and other variables may vary among sexual minority youth who are not attending college; thus, future research that engages non-students is needed.

Though we examined denominational stance toward for same-sex marriage—an objective measure of support for sexual minorities (Oswald, Cuthbertson, Lazarevic, & Goldberg, 2010)—and the importance of religion in one’s life, we did not examine attending religious services or religiously based activities (e.g., youth groups). It may be that affirming messages, supportive members, affirming-gay resources or other aspects of one’s faith community have a positive impact on sexual minority youth. Future research should investigate these and other indicators of religiosity, perceptions of general and sexual-orientation support, and the availability and use of resources, for example, LGBT and ally discussion groups. Moreover, though we examined denominational stance on same-sex marriage as a protective factor, it is possible that at the congregational level an opposite position may prevail, or such issues might not be discussed; therefore, examining religious teachings and messages at the local level is recommended. Further, research highlights the instrumental role of family and other members of one’s faith community in helping to shape heterosexual congregants’ understanding of homosexuality (Moon, 2004). Similarly, it is possible that sexual minority youth’s experiences with others in their faith communities may also moderate denominational stances, congregational messages, and mental health outcomes. All of these aspects of religion will be important to examine to better understand the intersection between sexuality, religion, discrimination, and mental health.

It will also be important to investigate “competing selves,” when one feels one’s sexual orientation is at odds with one’s religious doctrines (Sherry, Adelman, Whilde, & Quick, 2010) as well as one’s religious reasoning (Harris et al., 2008). Future research should also explore possible differences between sexual minority subgroups (Vrangalova & Savin-Williams, 2012), including by gender and race, and should also examine level of disclosure of sexual identity.

Conclusion

Minority stress theory (Meyer, 2003) highlights the pivotal role a negative social environment can have on sexual minority individuals’ health. This study extended minority stress research by demonstrating that having an element of a positive social environment (e.g., affirming religious affiliation) can mitigate negative experiences of interpersonal discrimination. Our study suggested it is important for mental health researchers to examine religious affiliation when engaging sexual minority youth; however, our results highlighted the need to examine the denomination’s stance toward same-sex sexuality. Although often considered at odds, minority sexuality and religion–under particular circumstances–may offer important benefits to the psychological well-being of sexual minority youth.

References

Abdel-Khalek, A. M., & Naceur, F. (2007). Religiosity and its association with positive and negative emotions among college students from Algeria. Mental Health, Religion, & Culture, 10, 159–170.

Anderson, A. L. (1998). Strengths of gay male youth: An untold story. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 15, 55–71.

Arnett, J. J. (2000). Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist, 55, 469–480.

Bolton, S. L., & Sareen, J. (2011). Sexual orientation research and its relation to mental disorders and suicide attempts: Findings from a nationally representative sample. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 56, 35–43.

Boxer, A. M., & Cohler, B. J. (1989). The life course of gay and lesbian youth: An immodest proposal for the study of lives. Journal of Homosexuality, 17, 315–355.

California Catholic Conference. (2008). Statements on same-sex marriage. Origins, 38, 117–119.

Chakraborty, A., McManus, S., Brugha, T. S., Bebbington, P., & King, M. (2011). Mental health of the non-heterosexual population of England. British Journal of Psychiatry, 198, 143–148.

Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints. (2008). Same-sex marriage and Proposition 8. Newsroom. Retrieved from http://www.mormonnewsroom.org/article/same-sex-marriage-and-proposition-8. Accessed 04 April 2012.

D’Augelli, A. R., Grossman, A. H., Salter, N. P., Vasey, J. J., Starks, M. T., & Sinclair, K. O. (2005). Predicting the suicide attempts of lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth. Suicide and Life Threatening Behavior, 35, 646–660.

D’Augelli, A. R., Pilkington, N. W., & Hershberger, S. L. (2002). Incidence and mental health impact of sexual orientation victimization of lesbian, gay and bisexual youths in high school. School Psychology Quarterly, 17, 148–167.

Dahl, A. L., & Galliher, R. V. (2009). LGBQQ young adult experiences of religious and sexual identity integration. Journal of LGBT Issues in Counseling, 3, 92–112.

Dahl, A. L., & Galliher, R. V. (2010). Sexual minority young adult religiosity, sexual orientation conflict, self-esteem, and depressive symptoms. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Mental Health, 14, 271–290.

Derogatis, L. R. (1975). Brief symptom inventory. Baltimore: Clinical Psychometric Research.

Dessel, A. B., Woodford, M. R., & Warren, N. (2011). Intergroup dialogue courses on sexual orientation: Lesbian, gay and bisexual student experiences and outcomes. Journal of Homosexuality, 58, 1132–1150.

Eisenberg, D., Gollusk, S. E., Golberstein, E., & Hefner, J. L. (2007). Prevalence and correlates of depression, anxiety, and suicidality among university students. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 77, 534–542.

Eliason, M. J., Burke, A., van Olphen, J., & Howell, R. (2011). Complex interactions of sexual identity, sex/gender, and religious/spiritual identity on substance use among college students. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 8, 117–125.

Ellison, C. G., Finch, B. K., Ryan, D. N., & Salinas, J. J. (2009). Religious involvement and depressive symptoms among Mexican-origin adults in California. Journal of Community Psychology, 37, 171–193.

Espelage, D. L., Aragon, S. R., Birkett, M., & Koenig, B. (2008). Homophobic teasing, psychological outcomes, and sexual orientation among high school students: What influences do parents and schools have? School Psychology Review, 37, 202–216.

Fenaughty, J., & Harre, N. (2003). Life on the seesaw: A qualitative study of resiliency factors for young gay men. Journal of Homosexuality, 45(1), 1–22.

Finlay, B., & Walther, C. S. (2003). The relation of religious affiliation, service attendance, and other factors to homophobic attitudes among university students. Review of Religious Research, 44, 370–393.

Fowler, J. W. (1981). Stages of faith: The psychology of human development and the quest for meaning. New York: Harper & Row.

Fraser, M. W., Galinsky, M. J., & Richman, J. M. (1999). Risk, protection and resilience: Toward a conceptual framework for social work practice. Social Work Research, 23, 131–143.

Ganzevoort, R. R., van der Laan, M., & Olsman, E. (2011). Growing up gay and religious: Conflict, dialogue, and religious identity strategies. Mental Health, Religion, & Culture, 14, 209–222.

Garcia, D., Gray-Stanley, J., & Ramirez-Valles, J. (2008). “The priest obviously doesn’t know that I’m gay”: The religious and spiritual journals of Latino gay men. Journal of Homosexuality, 55, 411–436.

Gartner, J., Larson, D. B., & Allen, G. D. (1991). Religious commitment and mental health: A review of the empirical literature. Journal of Psychology and Theology, 19, 6–25.

George, L. K., Ellison, C. G., & Larson, D. B. (2002). Explaining the relationships between religious involvement and health. Psychological Inquiry, 13, 190–200.

Goss, R. E., & West, M. (Eds.). (2000). Take back the word: A queer reading of the Bible. Cleveland: The Pilgrim Press.

Grace, A. P. (2008). The charisma and deception of reparative therapies: When medical science beds religion. Journal of Homosexuality, 55, 545–580.

Grossman, A. H., & Kerner, M. S. (1998). Self-esteem and supportiveness as predictors of emotional distress in gay male and lesbian youth. Journal of Homosexuality, 35, 25–39.

Hamblin, R. J., & Gross, A. M. (2014). Religious faith, homosexuality, and psychological well-being: A theoretical and empirical review. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Mental Health, 18, 67–82.

Harris, J. I., Cook, S. W., & Kashubeck-West, S. (2008). Religious attitudes, internalized homophobia, and identity in gay and lesbians adults. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Mental Health, 12, 205–225.

Heck, N. C., Flentje, A., & Cochran, B. N. (2011). Offsetting risks: High school gay-straight alliances and lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) youth. School Psychology Quarterly, 26, 161–174.

Higher Education Research Institute. (2008). 2008 cooperative institutional research program freshman survey questionnaire. Retrieved from http://www.heri.ucla.edu/researchers/instruments/CIRP/2008SIF.PDF. Accessed 04 April 2012.

Hilt, L. M., Cha, C. B., & Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (2008). Nonsuicidal self-injury in young adolescent girls: Moderators of the distress-function relationship. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 76, 63–71.

Jones, K. J. (2012). U.S. Catholic bishops reject ruling against Prop. 8. Catholic News Agency. Retrieved from http://www.catholicnewsagency.com/news/us-catholic-bishops-reject-ruling-against-prop.-8. Accessed 04 April 2012.

Kessler, R. C., Berglund, P., Demler, O., Jin, R., Merikangas, K. R., & Walters, E. E. (2005). Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62, 593–602.

Kinsey, A. C., Pomeroy, W. B., & Martin, C. E. (1948). Sexual behavior in the human male. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders Company.

Kralovec, K., Fartacek, C., Fartacek, R., & Plöderl, M. (2012). Religion and suicide risk in lesbian, gay, and bisexual Austrians. Journal of Religion and Health, 53, 413–423.

Lease, S. H., Horne, S. G., & Noffsinger-Frazier, N. (2005). Affirming faith experiences and psychological health for Caucasian lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 52, 378–388.

Levy, D. L. (2012). The importance of personal and contextual factors in resolving conflict between sexual identity and Christian upbringing. Journal of Social Service Research, 38, 56–73.

Longo, J., Walls, N. E., & Wisneski, H. (2012). Religion and religiosity: Protective or harmful factors for sexual minority youth? Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 16, 273–290.

Loosier, P. S., & Dittus, P. J. (2010). Group differences in risk across three domains using an expanded measure of sexual orientation. Journal of Primary Prevention, 31, 261–272.

Marshal, M. P., Dietz, L. J., Friedman, M. S., Stall, R., Smith, H. A., McGinley, J., … Brent, D. A. (2011). Suicidality and depression disparities between sexual minority and heterosexual youth: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Adolescent Health, 49, 115–123.

Mays, V. M., & Cochran, S. D. (2001). Mental health correlates of perceived discrimination among lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults in the United States. American Journal of Public Health, 91, 1869–1876.

McCullough, M. E., & Larson, D. B. (1999). Religion and depression: A review of the literature. Twin Research, 2, 126–136.

Meyer, I. H. (1995). Minority stress and mental health in gay men. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 36, 38–56.

Meyer, I. H. (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 129, 674–697.

Moon, D. (2004). God, sex, & politics: Homosexuality and everyday theologies. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Mustanski, B., Newcomb, M. E., & Garofalo, R. (2011). Mental health of lesbian, gay, and bisexual youths: A developmental resiliency perspective. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services, 23, 204–225.

Newcomb, M. E., & Mustanski, B. (2010). Internalized homophobia and internalizing mental health problems: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 30, 1019–1029.

Oswald, R. F., Cuthbertson, C., Lazarevic, V., & Goldberg, A. E. (2010). New developments in the field: Measuring community climate. Journal of GLBT Family Studies, 6, 214–228.

Pew Research Center. (2012). Religious groups’ official positions on same-sex marriage. Retrieved from http://www.pewforum.org/Gay-Marriage-and-Homosexuality/Religious-Groups-Official-Positions-on-Same-Sex-Marriage.aspx. Accessed 11 July 2013.

Rankin, S., Weber, G., Blumenfeld, W., & Frazer, S. (2010). 2010 state of higher education for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people. Charlotte: Campus Pride.

Rivers, I., & Noret, N. (2008). Well-being among same-sex- and opposite-sex-attracted youth at school. School Psychology Review, 37, 174–187.

Rostosky, S. S., Danner, F., & Riggle, E. D. B. (2007). Is religiosity a protective factor against substance use in young adulthood? Only if you’re straight! Journal of Adolescent Health, 40, 440–447.

Rowen, C. J., & Malcolm, J. P. (2002). Correlates of internalized homophobia and homosexual identity formation in a sample of gay men. Journal of Homosexuality, 43, 77–92.

Russell, S. T. (2005). Beyond risk: Resilience in the lives of sexual minority youth. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Issues in Education, 2, 5–18.

Saewyc, E. M., Homma, Y., Skay, C. L., Bearlinger, L. H., Resnick, M. D., & Reis, E. (2009). Protective factors in the lives of bisexual adolescents in North America. American Journal of Public Health, 99, 110–117.

Schuck, K. D., & Liddle, B. J. (2001). Religious conflicts experienced by lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Psychotherapy, 5, 63–82.

Sherry, A., Adelman, A., Whilde, M. R., & Quick, D. (2010). Competing selves: Negotiating the intersection of spiritual and sexual identities. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 41, 112–119.

Silverschanz, P., Cortina, L. M., Konik, J., & Magley, V. J. (2008). Slurs, snubs, and queer jokes: Incidence and impact of heterosexist harassment in academia. Sex Roles, 58, 179–191.

Smith, T. B., McCullough, M. E., & Poll, J. (2003). Religiousness and depression: Evidence for a main effect and the moderating influence of stressful life events. Psychological Bulletin, 129, 614–636.

Smith, C., & Snell, P. (2009). Souls in transition: The religious and spiritual lives of young adults. New York: Oxford University Press.

Swendsen, J. D., & Merikangas, K. R. (2000). The comorbidity of depression and substance use disorders. Clinical Psychology Review, 20, 173–189.

Ueno, K. (2010). Same-sex experience and mental health during the transition between adolescence and young adulthood. Sociological Quarterly, 51, 484–510.

Vrangalova, Z., & Savin-Williams, R. C. (2012). Mostly heterosexual and mostly gay/lesbian: Evidence for new sexual orientation identities. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 41, 85–101.

Walker, J. J., & Longmire-Avital, B. (2013). The impact of religious faith and internalized homonegativity on resiliency for black lesbian, gay, and bisexual emerging adults. Developmental Psychology, 49, 1723–1731.

Walls, N. E., Laser, J., Nickels, S. J., & Wisneski, H. (2010). Correlates of cutting behavior among sexual minority youths and young adults. Social Work Research, 34, 213–226.

Wheaton, B. (1985). Models for the stress-buffering functions of coping resources. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 26, 352–364.

Williams, K. A., & Chapman, M. V. (2011). Comparing health and mental health needs, service use, and barriers to services among sexual minority youths and their peers. Health and Social Work, 36, 197–206.

Williams, T., Connolly, J., Pepler, D., & Craig, W. (2005). Peer victimization, social support, and psychosocial adjustment of sexual minority adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 34, 471–482.

Woodford, M. R., Han, Y., Craig, S., Lim, C., & Matney, M. M. (2014). Discrimination and mental health among sexual minority college students: The type and form of discrimination does matter. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Mental Health, 18, 142–163.

Woodford, M. R., Krentzman, A. R., & Gattis, M. N. (2012a). Alcohol and drug use among sexual minority college students and their heterosexual counterparts: The effects of experiencing and witnessing incivility and hostility on campus. Substance Abuse and Rehabilitation, 3, 11–23.

Woodford, M. R., Levy, D., & Walls, N. E. (2013). Sexual prejudice among Christian college students, denominational teachings, and personal religious beliefs. Review of Religious Research, 55, 105–130.

Woodford, M. R., Walls, N. E., & Levy, D. L. (2012b). Religion and endorsement of same-sex marriage: The role of syncretism between denominational teachings about homosexuality and personal religious beliefs. Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion, 8, 1–29.

Wright, E. R., & Perry, B. R. (2006). Sexual identity distress, social support, and the health of gay, lesbian, and bisexual youth. Journal of Homosexuality, 51, 81–110.

Acknowledgments

Funding to support this study was received from the National Center on Institutional Diversity, University of Michigan and the Curtis Center, School of Social Work, University of Michigan. This article was supported by the Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) program, previously through the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR) grant 1UL1RR025011, and now by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) Grant 9U54TR000021. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. We thank Drs. Lonnie Berger, Jan Greenberg, Denise Levy, Stephanie Robert, and Eugene Walls, for reviewing earlier drafts.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gattis, M.N., Woodford, M.R. & Han, Y. Discrimination and Depressive Symptoms Among Sexual Minority Youth: Is Gay-Affirming Religious Affiliation a Protective Factor?. Arch Sex Behav 43, 1589–1599 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-014-0342-y

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-014-0342-y