Abstract

Context:

Motor impairments in individuals with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) have been frequently reported. In this review, we narrow our focus on postural control impairments to summarize current literature for patterns, underlying mechanisms, and determinants of posture in this population.Evidence Acquisition:

A literature search was conducted through Medline, ISI web of Knowledge, Scopus and Google Scholar to include studies between 1992 and February 2013.Results:

Individuals with ASD have problems in maintaining postural control in infancy that well persists into later years. However, the patterns and underlying mechanisms are still unclear.Conclusions:

Examining postural control as an endophenotype or early diagnostic marker of autism is a conceptual premise which should be considered in future investigations. At the end of the review, methodological recommendations on the assessment of postural control have also been provided.Keywords

1. Context

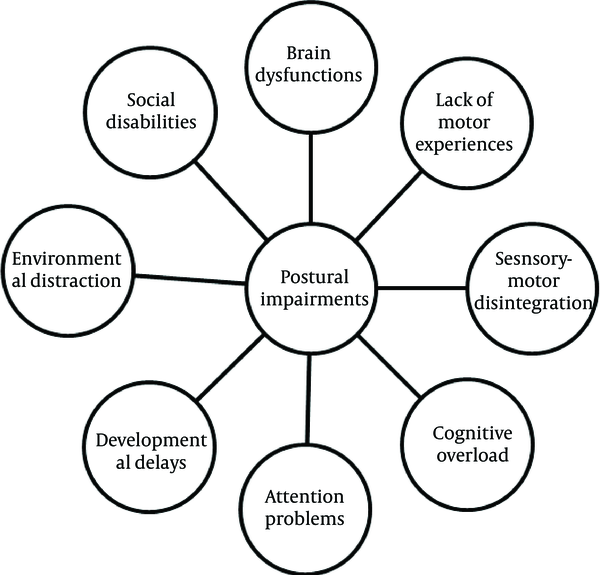

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a child-onset chronic neurodevelopmental condition which affects approximately 1 in 88 children, while its prevalence continues to rise (1, 2). This childhood disorder is characterized by core impairments in social/communication and repetitive behaviors (3). However, there are other clinical presentations which should be considered. Children with ASD have impairments in fine and gross motor skills, motor planning, motor coordination, and praxis (4-6). These patterns that may be observed in each motor development milestone may be considered as early warnings for ASD (6-8). Data indicates that impaired motor functions may be present before social problems or at least suggests that there is a strong association of social and motor functioning (5, 9). Although posture is a fundamental skill for children’s development, it can further affect learning opportunities of other perceptual-motor skills in children. Thus abnormal postural control can exacerbate ASD core symptoms by limiting the social interactions (9). Studies over recent decades about motor impairments in children with ASD have been summarized in three review articles (5, 10, 11). Although these papers included wide array of impairments in general motor domains among children with ASD; surprisingly, none of them reviewed posture exclusively. Previous studies on posture in children with ASD have applied different sample size, sex, age, inclusion criteria (high or low IQ participants), methodological assessments (subjective or objective), and subgroups of ASD (Aperger’s or autism) which resulted in some inconsistencies. For example, Figure 1 provides a conceptual diagram illustrating possible factors contributing to postural control impairments in ASD, though the interactions and the extent, to which they are involved, are still not clear.

Contributing Factors in Postural Control Impairments

This brief provides a critical overview of what we know and what we don't know in the domain of postural control in ASD, discusses strengths and weaknesses of the current research, and finally gives further suggestions for research in postural control in individuals with ASD.

2. Evidence Acquisition

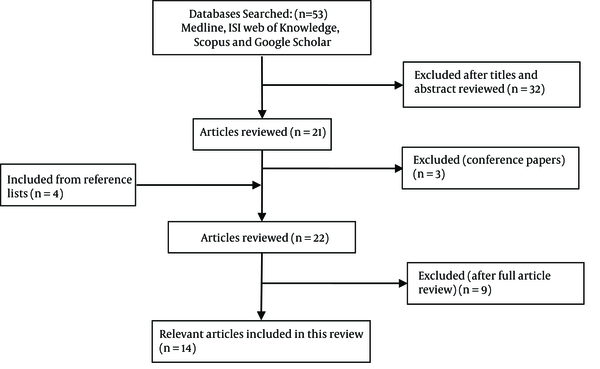

A literature search was carried out using Medline, ISI web of Knowledge, Scopus and Google Scholar to include studies between 1992 and February 2013. Keywords used in the search strategy included “Pervasive developmental disorder”, “ASD”, “Aperger’s”, “autism”, “postural stability”, “postural control”, “postural sway”, “stability”, “posture”, “balance”, and “motor skills”. Exclusion criteria included abstracts which were presented in the conferences, papers in which presenting the search terms in only abstract without describing in the main part and articles that were not written in English. Also, we excluded papers concerning general motor behaviors instead of postural control in individuals with ASD. The initial search of the databases, containing all the keywords, yielded 53 results. Applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 14 studies were selected to critically review of postural control in individuals with ASD. Figure 2 illustrates the structure of the literature review.

Flowchart of Literature Review Process

3. Results

3.1. Early Impairments

Infants later diagnosed with ASD show peculiar movements and delayed motor milestones. Asymmetrical posture in lying on the stomach at the age of 4 months will remain throughout the first year of life (6, 8). In the rolling stage, while some autistic infants cannot perform it at all, others are only unable to follow motor sequence and consequently show deviated patterns compared with typically developing (TD) peers. Also, some autistic children achieve the ability of sitting later than 6 months of age which is expected for normal babies. However, asymmetrical weight distribution on both sides in sitting posture increases the falling forward or backward (6, 12). In the crawling phase, children with ASD are likely to show asymmetry and asynchronization of weight shifting so that they are unable to perform diagonal patterns of legs and arms required in crawling (6, 13). There is far too little information about standing patterns in autistic infants at the age of 8-10 months. The sign of akinesia for a period of 15 minutes was shown in an autistic girl who stood in a place when leaning at heavy furniture, while a TD child in this age only stands a few minutes and falls to the ground (6). However, the study by Esposito et al. could not demonstrate a significant difference in standing of infants with ASD compared with TD counterparts (12). The most investigated phase is the stage of walking in which children with ASD demonstrated obvious delayed walking, parkinsonian-type pattern, short steps, and asymmetrical gait compared with their TD peers (6, 12, 14). Asymmetrical postures and delayed or deviated motor patterns in infants with ASD might be explained by dysregulation of infantile reflexes, which either are not inhibited at the appropriate age or not triggered when they should. Furthermore, regarding the role of the vestibular system in controlling the mutual interaction of sensory input and motor outputs, and also in the pathogenesis of autism, its dysfunction will be another possible contributing factor in postural control impairments in ASD (6, 7, 13, 14).

3.2. Late Impairments

Postural control impairments track from infancy to childhood and even later years. Children with ASD showed a decreased static and dynamic postural stability, functional balance, and motor performance. Kohen-Raz et al. compared postural stability in 91 autistic children aged 6-20 years old with 166 TD children by tetra-ataxiametric method (15). They reported a higher postural instability and increased weight distribution in children with ASD (16-18). Although there is a regular improvement in postural control of TD children from age five; ASD investigations demonstrate a different pattern. Postural control does not begin to improve untill the age of 12 years and never achieves the adult level in children with ASD (19). Another sign of postural immaturity in children with ASD is an abnormal asymmetry in the direction of instability. Children with ASD show higher postural instability in medio-lateral compared to anteroposterior direction; whereas, TD peers show a reverse pattern (15, 16). While this pattern in ASD looks like the primitive pattern of postural control in toddlers, authors explain that an asynchrony in postural stabilizing muscles may be responsible for this unusual development of postural control in ASD (16).

3.3. Contributing Factors

Successful postural control requires comprehensive integration of somatosensory, vestibular, and visual inputs. Children with ASD can be distinguished from their TD counterparts when sensory information is disrupted. Posturography of 79 autistic individuals under different conditions with sensory challenges showed that autistic children exhibit more postural instability when somatosensory or proprioceptive inputs are restricted (19). Another study demonstrated that visual occlusion and sensory perturbations exacerbate postural control of boys with ASD (17). Authors mentioned that children with ASD tend to rely more on sensory information such as visual inputs in order to maintain postural control. In contrast, Kohen-Raz et al. found that individuals with ASD show better stability when somatosensory input was restricted (15). They explained that this paradoxical postural response may be derived from an overlap of activations in cerebellar regions which are involved in filtering and regulating sensory inputs. This overlap may compensate weak postural control in children with ASD. Also, lower mesocortical motor regions of the brain may be activated under challenging sensory conditions in order to keep posture (15). However, it seems that, at least in part, uncontrolled visual and auditory sensory inputs in their experimental setting, induced low functioning autistic individuals to show such paradoxical postural responses (15, 17, 19). Vision plays a crucial role in regulating individuals’ orientation and postural control. In everyday activities, postural control is mostly accompanied by a visual task. This concurrent visual task (such as environmental motions) may alter the patterns of postural sway and interfere with the ability of postural control. Postural sway induced by visual motion in individuals with ASD was first investigated in a study of 5 autistic children aged 4-7 years (20). Surprisingly, children with ASD showed no effects of moving visual scene on postural control probably due to inattentiveness to visual stimuli (20). A few years later, Gepner et al. replicated the study to compare postural reactivity in autism, Asperger’s and TD groups (21). In contrast to their early observations, they found that children with autism show postural hyporeactivity to fast visual motion stimuli (20), though both Asperger and TD groups exhibit a tuned postural response to visual motion flow (21). They mentioned that children with low functioning autism have weak visuopostural tuning in contrast to children with high functioning autism. Recently, another study has examined postural responses to ongoing visual stimuli using a visual tunnel system in a larger sample size of ASD (22). This paradigm minimizes visual inattentiveness discussed previously (20, 21). Findings confirm the postural hyporeactivity in autistic children besides, when seeing fast visual flow, younger autistic children show better postural control than TD counterparts (22). These findings suggest that postural reactivity in ASD induced by visual information is dependent upon both developmental factors and visual stimuli properties (i.e. speed). Impairments in dorsal stream as well as visuocerebellar pathways may result in higher threshold for motion perception, multisensory integration, and sensorimotor tuning (20-22). Indeed abnormal postural rigidity and freezing like strategies may hamper postural responses to visual flow in some autistic children though over tuning and postural flexibility to visual flow can lead to degrees of motor clumsiness in the others (i.e. Asperger) (21, 23). Additionally, perceptual and cognitive demands of concurrent visual tasks can alter postural control in ASD. Memari et al. showed that in addition to primary differences in patterns of postural control between ASD and TD groups, visual and auditory tasks may differently influence the postural control in children with ASD but not TD children (16). However in another recent study Chang et al. examining the effects of inspection versus searching visual tasks on standing posture of children with ASD (24), revealed that possibly ASD does not change the ability of postural control during a dual task though ASD may havewindo particular effects only for specific types of secondary tasks which have not been elucidated yet (24).

3.4. Underlying Brain Mechanisms

Neuroanatomical and behavioral studies demonstrated that several brain regions are involved in motor control abnormalities in individuals with ASD. Structural and functional impairments in the cerebellum and the basal ganglia seem to be responsible for postural control impairments (25). Findings indicated that the cerebellum as the main region contributing to sensory integration shows developmental hypoplasia in children with ASD. This may directly hamper motor functions or indirectly affect it through its connections with brain stem, thalamus, and hypothalamus (26). Besides, dysfunctions of the basal ganglia circuits have been implicated to associate with Parkinsonian like posture in individuals with ASD. Although both cerebellum and basal ganglia are involved to some extent in each subcategory of ASD, the different patterns of motor impairments in autism and Asperger’s is more likely to be consistent with cerebellar dysfunctions rather than basal ganglia (27). Furthermore, Galati et al. indicated that posterior parietal area around the intraparietal sulcus and frontal regions around the precentral and superior frontal sulci which provide multimodal integrated coding of visual and somatic sensory inputs may have deficits in children with ASD (28). Examining other contributing factors revealed a decreased activation in supplementary motor area and greater activation in prefrontal cortex in ASD (29). Also, abnormal volume of cerebral grey matter (30), reduced volume of the anterior cingulate (31), increased volume of the caudate (32) along with abnormal transmission in the dopaminergic (33), serotonergic (34), and GABAergic system (5) are likely to affect functional motor performance in children with ASD. Finally there is little discussion about possible neurobiological abnormalities underpinning clinical motor impairments and postural control immaturity in children with ASD.

3.5. Differential Diagnosis

There is a question of whether postural impairments are manifested in developmental disorders rather than ASD. Recently, it was found that in developmental disorders such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, Tourette syndrome, developmental coordination disorder, cerebral palsy, and hearing loss, children show some degrees of decrement in postural control (35-39). Thus, there is a hypothetical notion that emerging postural control impairments in individuals with ASD are due to developmental delays rather than the direct effects of ASD per sec (12). There are a few variations in patterns of postural control that may help to differentiate ASD from other similar disorders. A recent study found that autistic individuals rather than intellectually disabled individuals show paradoxically better postural control in challenging sensory conditions. Also, the weight displacement between heel and toe in autism is located on one foot or single heel or toe. This pattern is in agreement with what is assumed as atypical monopedal or/and tripodal stances in children with ASD (15). Minshew et al. revealed that reduced postural stability in autistic children is directly associated with ASD but not intellectual disability as a common comorbid condition (19). Accordingly, other studies demonstrated that severity of ASD has detrimental effects on postural stability (9, 15, 16), though Molloy et al. could not reveal any association (17). They explained that severe ASD symptoms may negatively affect cognitive and motor abilities which result in a poor postural control (16, 40).

3.6. Assessment methodologies

Reviewing literature shows that different posturography methods other than different postural control parameters have been used. It is worth mentioning that each measurement tool is able to examine a specific aspect of postural control due to the assessment procedure. Furthermore each sway parameter accounts for a specific marker of postural control; thus interpretation of findings should be based on careful definition of each variable and the instrument (for more details see Table 1 and 2).

| Variables | Definition |

|---|---|

| Center of gravity | The point in the body where it acts as if all mass were concentrated |

| Center of mass | The point where body mass is concentrated |

| Base of support | The area of interface between ground and feet |

| Center of pressure | Position of the ground reaction forces exerted to confront body weight |

| Root mean square | The estimated amplitude of center of pressure fluctuations |

| Mean velocity | The average speed of center of pressure movements |

| Sway area | The surface which is covered by center of pressure path in a period of time |

| Mean frequency | The frequency of the COP movement if it had traveled in a circle shape with the radius of mean distance |

| Center of pressure – center of mass | Interaction of center of pressure and center of mass which shows segment movements |

| postural perturbations | Root mean square of total body velocity in angle per second |

| Adaptation ratio; toes-up/toes-down | The ability of subject to adapt to repeated platform rotation |

| Stability index | The total amount of sway divided by the weight of the individual |

| Spectral quotient | The lower frequency range vs. three subsequent higher frequency waves |

| Weight distribution | The standard deviation of four weight distribution scores |

| Synchronization score | A correlation like index which indicates two paired waves if they are coordinated |

Postural Control Assessment Tools and Methods

| Tools and Methods | Explanation |

|---|---|

| Motion tracker system | This method records joint movements of body by sensors placed on it |

| Equi test | This method records the position of vertical forces exerted by individuals’ feet under 6 sensory conditions by a dual forceplate |

| Tetra-ataxiametry | The method which measures vertical forces by four foot plates, one for each heel and toe, assesses both the weight distribution and sway fluctuations |

| Force platform | A commonly used instrument which records the ground reaction forces and center of pressure generated by a standing subject |

| Video analysis | A rater watches a video from a participant and gives scores based on the codes of different variables such as angles of the joints and then analyses the data |

4. Conclusions

Data show that findings on postural control patterns and contributing factors in individuals with ASD are still in infancy. From the few existing data, it is already clear that individuals with ASD demonstrate different patterns of postural control. However one critical aspect of current literature is that studies dominantly compared postural sway of ASD only with healthy groups. The lack of another control group with any developmental delay makes interpretations hard on the role of autism against the developmental delay. It is already known that sensorimotor, visual and auditory system interactions may be important contributing factors in postural control of ASD. However it is suggested that these systems differently affect postural control as some recent findings highlight the role of visual inputs in ASD (17). Examining other contributing factors, studies use dual task paradigms to investigate attentional resources required for postural control. It is already known that the kind of cognitive task and its complexity may affect the postural control. However the effect of interventions such as motor training or cognitive enhancement on the outcome of dual task postural control should be addressed in different samples with ASD by future studies (41). A critical point about contributing factors refers to heterogeneity of studied samples with ASD that refrains from drawing definite conclusions. It is unknown how severity of disorder and level of IQ can affect postural control in ASD though findings suggest that level of IQ and autism symptoms severity may reflect sensory impairments (19, 42, 43). Furthermore, given the co-occurrence of ASD with other psychiatric or neurological disorders (44), postural abnormalities may be on account of these syndromes. Finally sociodemographic variables may be useful to explore carefully. For example while gender is not considered to affect postural control in normal population, Minshew et al. found significant effects of gender on postural control in ASD which may be due to the different nature of disorder across genders (19). We already know that postural control impairments start appearing from early years in ASD. This may present as an endophenotype in ASD and findings are suggestive for including postural control assessment as an early marker of ASD. However, there is little data to indicate whether postural control impairments in ASD are resolved in adulthood. Although Travers et al. revealed that adults with ASD aged 16-30 do not differ in bipedal stance from that of TD counterparts (9), Minshew et al. found that individuals with ASD aged 5-52 show postural instability compared with control group (19). It is worth mentioning that general motor impairments in addition to low participation in physical activities, games, and sports hampers motor experiences and decreases learning opportunities which may limit postural control improvements in individuals with ASD. Overall, the underlying mechanisms of postural control impairments in population with ASD still remain unclear. The co-occurrence of a broad range of brain deficits in the population with ASD and presence of a wide of range problems in attention, perception, learning, and motor behaviors overshadow the brain regions potentially linked to postural control impairments (5, 19, 45). Hence, functional brain imaging and electrophysiological assessments can add valuable data about brain regions and activation patterns which contribute to postural control impairments in ASD.

4.1. Recommendations

Although several different methods of posturography have been used to evaluate postural control in ASD, the following recommendations are intended to help move postural assessment studies forward and to provide researchers with guidelines to establish standards of practice for these studies (Table 3). Use of these guidelines will improve our ability to compare study results and interpret postural control Patterns in ASD. This will also improve our understanding of the mechanisms by which postural control contributes in health of individuals with ASD.

Recommendations for Future Studies of Postural Control in Individuals With Autism Spectrum Disordera

| Recommendations | |

|---|---|

| 1 | In children studies, participation should be at least 10 subjects per age group (i.e. 8–10, 10–12 y). As maturity and body mass is known to be a major contributing factor in the pattern of postural control, findings should be age specific. |

| 2 | Recruiting population with ASD with different levels of IQ (high and low functioning) can be helpful to explore if IQ is associated with postural control. |

| 3 | Studies should consider recruiting both genders since there is too little data on postural control in females with ASD. |

| 4 | In addition to infancy and childhood, postural control should be investigated in ASD adulthood carefully. |

| 5 | It is suggested to complete familiarization process with the testing protocol by a storyboard or practicing it several times prior the main test. The anxiety is a commonly observed problem in individuals with ASD that should be considered by examiners. |

| 6 | Investigating postural control in individuals with broader autism phenotype (BAP) may help to find if this motor behavior has a genetic basis. |

| 7 | Future studies are suggested to include control groups from other developmental disorders rather than healthy groups such as children with motor delays. |

| 8 | To have a homogenous and comparable methodology, different studies are supposed to consider at least 30 s for duration of each trial. Also, the position of head, feet, and hands should be taken into account when data of postural control are recorded. |

| 9 | Examining dual task paradigms, examiners should include different kinds of cognitive tasks (i.e. visual, auditory, etc.) with different levels of complexity. |

| 10 | Using multiple methods of assessments such as video analyses besides posturography (e.g. force platform) in different contexts reduces biases and provides more comprehensive data on postural control in ASD. |

| 11 | Applying functional and anatomical brain imaging along with behavioral approaches can be helpful to examine possible underlying mechanisms of postural control in ASD. |

| 12 | It is highly important to control the possible confounding variables such as severity of disorder, medication list and co-morbid conditions when assessing postural control in individuals with ASD. |

| 13 | Since each postural sway parameter accounts for a specific marker, they could not be used interchangeably and with the same meaning. |

Acknowledgements

References

-

1.

Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network Surveillance Year Principal I, Centers for Disease C. Prevalence of autism spectrum disorders--Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 14 sites, United States, 2008. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2012;61(3):1-19. [PubMed ID: 22456193].

-

2.

Matson JL, Kozlowski AM. The increasing prevalence of autism spectrum disorders. Res Autism Spectr Disord. 2011;5(1):418-25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2010.06.004.

-

3.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental. 4th ed. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

-

4.

Ming X, Brimacombe M, Wagner GC. Prevalence of motor impairment in autism spectrum disorders. Brain Dev. 2007;29(9):565-70. [PubMed ID: 17467940]. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.braindev.2007.03.002.

-

5.

Fournier KA, Hass CJ, Naik SK, Lodha N, Cauraugh JH. Motor coordination in autism spectrum disorders: a synthesis and meta-analysis. J Autism Dev Disord. 2010;40(10):1227-40. [PubMed ID: 20195737]. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-010-0981-3.

-

6.

Teitelbaum P, Teitelbaum O, Nye J, Fryman J, Maurer RG. Movement analysis in infancy may be useful for early diagnosis of autism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95(23):13982-7. [PubMed ID: 9811912].

-

7.

Flanagan JE, Landa R, Bhat A, Bauman M. Head lag in infants at risk for autism: a preliminary study. Am J Occup Ther. 2012;66(5):577-85. [PubMed ID: 22917124]. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2012.004192.

-

8.

Esposito G, Venuti P, Maestro S, Muratori F. An exploration of symmetry in early autism spectrum disorders: analysis of lying. Brain Dev. 2009;31(2):131-8. [PubMed ID: 18534798]. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.braindev.2008.04.005.

-

9.

Travers BG, Powell PS, Klinger LG, Klinger MR. Motor difficulties in autism spectrum disorder: linking symptom severity and postural stability. J Autism Dev Disord. 2013;43(7):1568-83. [PubMed ID: 23132272]. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-012-1702-x.

-

10.

Downey R, Rapport MJ. Motor activity in children with autism: a review of current literature. Pediatr Phys Ther. 2012;24(1):2-20. [PubMed ID: 22207460]. https://doi.org/10.1097/PEP.0b013e31823db95f.

-

11.

Emck C, Bosscher R, Beek P, Doreleijers T. Gross motor performance and self-perceived motor competence in children with emotional, behavioural, and pervasive developmental disorders: a review. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2009;51(7):501-17. [PubMed ID: 19538424]. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8749.2009.03337.x.

-

12.

Esposito G, Venuti P. Symmetry in infancy: analysis of motor development in autism spectrum disorders. Symmetry. 2009;1(2):215-25. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym1020215.

-

13.

Teitelbaum O, Benton T, Shah PK, Prince A, Kelly JL, Teitelbaum P. Eshkol-Wachman movement notation in diagnosis: the early detection of Asperger's syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(32):11909-14. [PubMed ID: 15282371]. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0403919101.

-

14.

Bhat AN, Galloway JC, Landa RJ. Relation between early motor delay and later communication delay in infants at risk for autism. Infant Behav Dev. 2012;35(4):838-46. [PubMed ID: 22982285]. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infbeh.2012.07.019.

-

15.

Kohen-Raz R, Volkmar FR, Cohen DJ. Postural control in children with autism. J Autism Dev Disord. 1992;22(3):419-32. [PubMed ID: 1383190].

-

16.

Memari AH, Ghanouni P, Shayestehfar M, Ziaee V, Moshayedi P. Effects of visual search vs. auditory tasks on postural control in children with autism spectrum disorder. Gait Posture. 2014;39(1):229-34. [PubMed ID: 23931847]. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gaitpost.2013.07.012.

-

17.

Molloy CA, Dietrich KN, Bhattacharya A. Postural stability in children with autism spectrum disorder. J Autism Dev Disord. 2003;33(6):643-52. [PubMed ID: 14714933].

-

18.

Fournier KA, Kimberg CI, Radonovich KJ, Tillman MD, Chow JW, Lewis MH, et al. Decreased static and dynamic postural control in children with autism spectrum disorders. Gait Posture. 2010;32(1):6-9. [PubMed ID: 20400311]. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gaitpost.2010.02.007.

-

19.

Minshew NJ, Sung K, Jones BL, Furman JM. Underdevelopment of the postural control system in autism. Neurology. 2004;63(11):2056-61. [PubMed ID: 15596750].

-

20.

Gepner B, Mestre D, Masson G, de Schonen S. Postural effects of motion vision in young autistic children. Neuroreport. 1995;6(8):1211-4. [PubMed ID: 7662910].

-

21.

Gepner B, Mestre DR. Brief report: postural reactivity to fast visual motion differentiates autistic from children with Asperger syndrome. J Autism Dev Disord. 2002;32(3):231-8. [PubMed ID: 12108625].

-

22.

Greffou S, Bertone A, Hahler EM, Hanssens JM, Mottron L, Faubert J. Postural hypo-reactivity in autism is contingent on development and visual environment: a fully immersive virtual reality study. J Autism Dev Disord. 2012;42(6):961-70. [PubMed ID: 21751061]. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-011-1326-6.

-

23.

Weimer AK, Schatz AM, Lincoln A, Ballantyne AO, Trauner DA. "Motor" impairment in Asperger syndrome: evidence for a deficit in proprioception. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2001;22(2):92-101. [PubMed ID: 11332785].

-

24.

Chang CH, Wade MG, Stoffregen TA, Hsu CY, Pan CY. Visual tasks and postural sway in children with and without autism spectrum disorders. Res Dev Disabil. 2010;31(6):1536-42. [PubMed ID: 20598853]. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2010.06.003.

-

25.

Nayate A, Bradshaw JL, Rinehart NJ. Autism and Asperger's disorder: are they movement disorders involving the cerebellum and/or basal ganglia? Brain Res Bull. 2005;67(4):327-34. [PubMed ID: 16182941]. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brainresbull.2005.07.011.

-

26.

Courchesne E, Yeung-Courchesne R, Press GA, Hesselink JR, Jernigan TL. Hypoplasia of cerebellar vermal lobules VI and VII in autism. N Engl J Med. 1988;318(21):1349-54. [PubMed ID: 3367935]. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM198805263182102.

-

27.

Rinehart NJ, Tonge BJ, Bradshaw JL, Iansek R, Enticott PG, McGinley J. Gait function in high-functioning autism and Asperger's disorder : evidence for basal-ganglia and cerebellar involvement? Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;15(5):256-64. [PubMed ID: 16554961]. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-006-0530-y.

-

28.

Galati G, Committeri G, Sanes JN, Pizzamiglio L. Spatial coding of visual and somatic sensory information in body-centred coordinates. Eur J Neurosci. 2001;14(4):737-46. [PubMed ID: 11556898].

-

29.

Muller RA, Pierce K, Ambrose JB, Allen G, Courchesne E. Atypical patterns of cerebral motor activation in autism: a functional magnetic resonance study. Biol Psychiatry. 2001;49(8):665-76. [PubMed ID: 11313034].

-

30.

Lotspeich LJ, Kwon H, Schumann CM, Fryer SL, Goodlin-Jones BL, Buonocore MH, et al. Investigation of neuroanatomical differences between autism and Asperger syndrome. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61(3):291-8. [PubMed ID: 14993117]. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.61.3.291.

-

31.

Haznedar MM, Buchsbaum MS, Wei TC, Hof PR, Cartwright C, Bienstock CA, et al. Limbic circuitry in patients with autism spectrum disorders studied with positron emission tomography and magnetic resonance imaging. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(12):1994-2001. [PubMed ID: 11097966].

-

32.

Piven J, Arndt S, Bailey J, Andreasen N. Regional brain enlargement in autism: a magnetic resonance imaging study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1996;35(4):530-6. [PubMed ID: 8919716]. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-199604000-00020.

-

33.

Barthelemy C, Bruneau N, Cottet-Eymard JM, Domenech-Jouve J, Garreau B, Lelord G, et al. Urinary free and conjugated catecholamines and metabolites in autistic children. J Autism Dev Disord. 1988;18(4):583-91. [PubMed ID: 3215884].

-

34.

Cook EH, Jr, Courchesne R, Lord C, Cox NJ, Yan S, Lincoln A, et al. Evidence of linkage between the serotonin transporter and autistic disorder. Mol Psychiatry. 1997;2(3):247-50. [PubMed ID: 9152989].

-

35.

Reilly DS, Woollacott MH, van Donkelaar P, Saavedra S. The interaction between executive attention and postural control in dual-task conditions: children with cerebral palsy. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2008;89(5):834-42. [PubMed ID: 18452729]. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2007.10.023.

-

36.

Laufer Y, Ashkenazi T, Josman N. The effects of a concurrent cognitive task on the postural control of young children with and without developmental coordination disorder. Gait Posture. 2008;27(2):347-51. [PubMed ID: 17532635]. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gaitpost.2007.04.013.

-

37.

Lemay M, Le TT, Richer F, Montreal Tourette Study G. Effects of a secondary task on postural control in children with Tourette syndrome. Gait Posture. 2010;31(3):326-30. [PubMed ID: 20022754]. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gaitpost.2009.11.017.

-

38.

Buderath P, Gartner K, Frings M, Christiansen H, Schoch B, Konczak J, et al. Postural and gait performance in children with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Gait Posture. 2009;29(2):249-54. [PubMed ID: 18963991]. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gaitpost.2008.08.016.

-

39.

Rine RM, Cornwall G, Gan K, LoCascio C, O'Hare T, Robinson E, et al. Evidence of progressive delay of motor development in children with sensorineural hearing loss and concurrent vestibular dysfunction. Percept Mot Skills. 2000;90(3 Pt 2):1101-12. [PubMed ID: 10939054]. https://doi.org/10.2466/pms.2000.90.3c.1101.

-

40.

Freitag CM, Kleser C, Schneider M, von Gontard A. Quantitative assessment of neuromotor function in adolescents with high functioning autism and Asperger Syndrome. J Autism Dev Disord. 2007;37(5):948-59. [PubMed ID: 17171541]. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-006-0235-6.

-

41.

Woollacott M, Shumway-Cook A. Attention and the control of posture and gait: a review of an emerging area of research. Gait Posture. 2002;16(1):1-14. [PubMed ID: 12127181].

-

42.

Liss M, Harel B, Fein D, Allen D, Dunn M, Feinstein C, et al. Predictors and correlates of adaptive functioning in children with developmental disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 2001;31(2):219-30. [PubMed ID: 11450820].

-

43.

Memari A, Ziaee V, Mirfazeli F, Kordi R. Investigation of autism comorbidities and associations in a school-based community sample. J Child Adolesc Psychiatr Nurs. 2012;25(2):84-90. [PubMed ID: 22512525]. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6171.2012.00325.x.

-

44.

Matson JL, Shoemaker M. Intellectual disability and its relationship to autism spectrum disorders. Res Dev Disabil. 2009;30(6):1107-14. [PubMed ID: 19604668]. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2009.06.003.

-

45.

Noterdaeme M, Mildenberger K, Minow F, Amorosa H. Evaluation of neuromotor deficits in children with autism and children with a specific speech and language disorder. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2002;11(5):219-25. [PubMed ID: 12469239]. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-002-0285-z.