Published online Aug 26, 2011. doi: 10.4330/wjc.v3.i8.278

Revised: July 18, 2011

Accepted: July 25, 2011

Published online: August 26, 2011

We report a case of essential thrombocythemia (ET) in a 30-year-old female who exhibited inferior wall ST-elevation acute myocardial infarction (AMI) without significant obstructive coronary artery disease. Right coronary vasospasm was observed after intra-coronary methylergonovine administration and she received verapamil 120 mg/d

thereafter and hydroxyurea 1500 mg/d for thrombocythemia. After discontinuation of the hydroxyurea for 9 mo based on the impression of coronary spasm-related instead of coronary thrombosis-related AMI, her platelet count rose but no chest pain was observed. It is suggested that coronary spasm potentially plays a role in patients with ET, AMI and no significant coronary artery stenosis.

- Citation: Cheng CW, Hung MJ. Coronary spasm-related acute myocardial infarction in a patient with essential thrombocythemia. World J Cardiol 2011; 3(8): 278-280

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8462/full/v3/i8/278.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4330/wjc.v3.i8.278

It has been reported that essential thrombocythemia (ET) causes coronary thrombosis and acute myocardial infarction (AMI), however, coronary spasm-related AMI in the setting of ET has rarely been reported[1,2]. With regard to ET and AMI, four cases have been reported where no significant obstructive coronary artery disease was demonstrated on coronary angiography[2-5]. By contrast, however, coronary vasospasm has never been demonstrated. Herein, we report the case of a female patient without significant obstructive coronary artery disease where right coronary vasospasm was provoked on coronary angiography after acute inferior wall ST-elevation myocardial infarction.

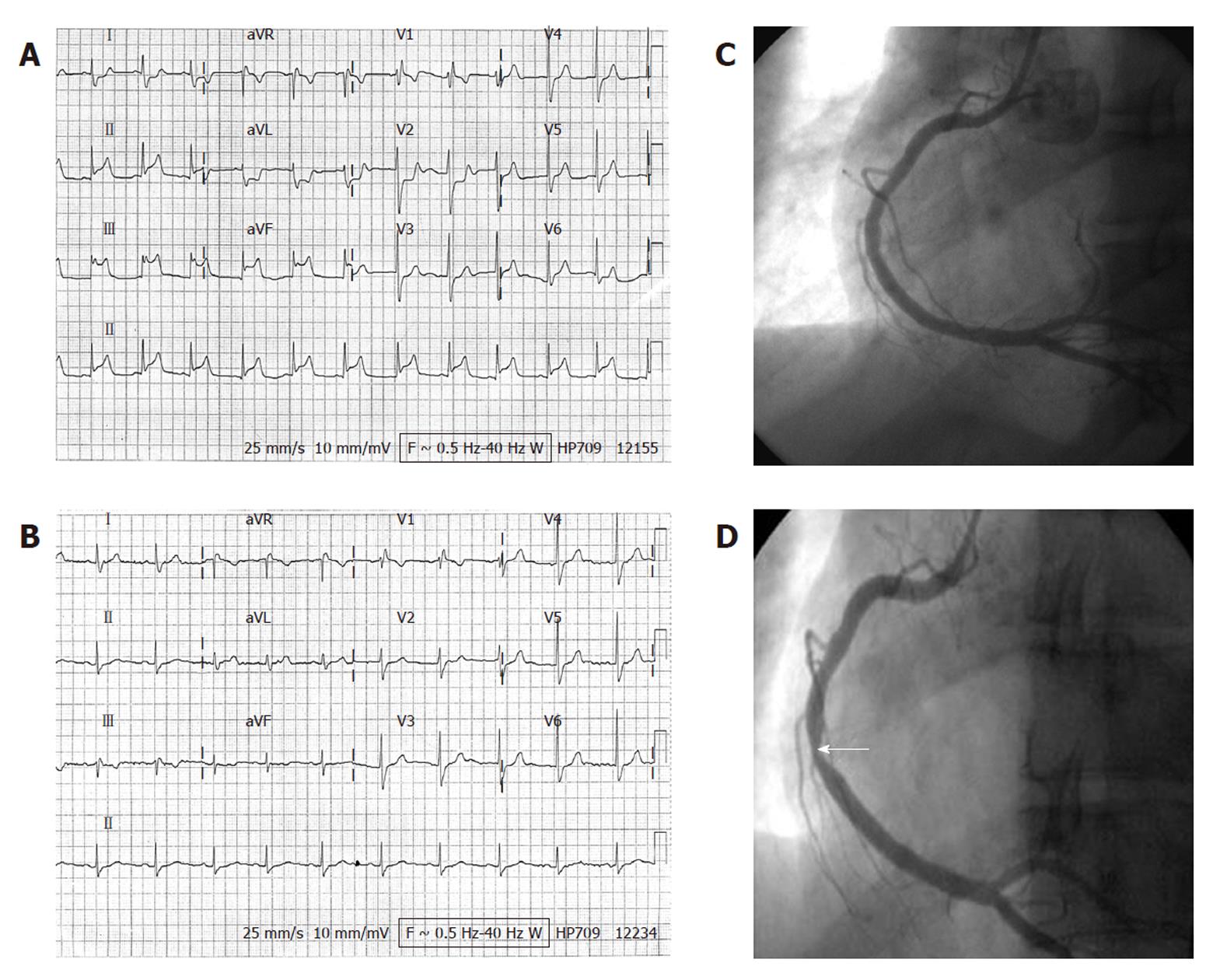

A 30-year-old woman with no history of heart disease was admitted to our hospital having suffered sudden-onset chest pain for the preceding 4 h. Associated diaphoresis had occurred. She denied a history of cigarette smoking, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, or hypercholesterolemia. There was no family history of premature coronary artery disease. Clinical examination of the patient revealed a heart rate of 70 beats per minute, respiratory rate of 17 breaths per minute, blood pressure of 114/62 mmHg, and no fever. Other findings of the physical examination were unremarkable. The 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) revealed ST-elevations at the inferior leads and incomplete right bundle branch block (Figure 1A). Heart and lungs were normal on chest X-ray. Complete blood count was 16 700/mm3 with normal differential count, hematocrit 38.6%, and platelet count of 1 277 000/mm3. Maximal serum cardiac troponin-I was 6.80 ng/mL and peak creatine kinase was 706 IU/L, with MB isoenzyme of 11.6%. High-sensitivity C-reactive protein was 4.29 mg/L. Total cholesterol was 148 mg/dL. Echocardiography revealed no abnormal wall motion and a left ventricular ejection fraction of 73%. The patient was immediately started on sublingual nitroglycerin, aspirin and clopidogrel with bolus doses of 325 and 300 mg then 100 mg and 75 mg, respectively, once daily, and subcutaneous enoxaparin 50 mg every 12 h for 48 h. She did not undergo primary coronary intervention or thrombolytic therapy because she felt no more chest pain after the initial treatments. The follow-up 12-lead ECG (Figure 1B) on day 2 showed no evolutional ST-T changes, which suggested a rapid resolution of coronary artery occlusion in this patient.

Coronary angiography on day 3 revealed no evidence of significant obstructive coronary artery disease (Figure 1C). Based on the possibility of dynamic coronary artery obstruction and coronary vasospasm-related electrocardiographic changes, intra-coronary methylergonovine was administered incrementally (1, 5, 10 and 30 μg) at 3 min intervals. After administration of 10 μg methylergonovine into the right coronary artery, a reduction in diameter of 90% was noted in its distal portion (Figure 1D) with concurrent chest pain. Intra-coronary nitroglycerin 100 μg was then administered, reversing the right coronary vasospasm. After coronary angiography, the patient was started on verapamil 120 mg once daily. A bone marrow study on day 10 revealed megakaryocytic hyperplasia consistent with ET. On the same day, the patient’s platelet count was 1 292 000/mm3. The hematologist suggested that thrombocythemia may have played a role in the development of AMI, and hydroxyurea was prescribed. The patient was discharged on day 12 with verapamil 120 mg once daily and hydroxyurea 500 mg three times daily.

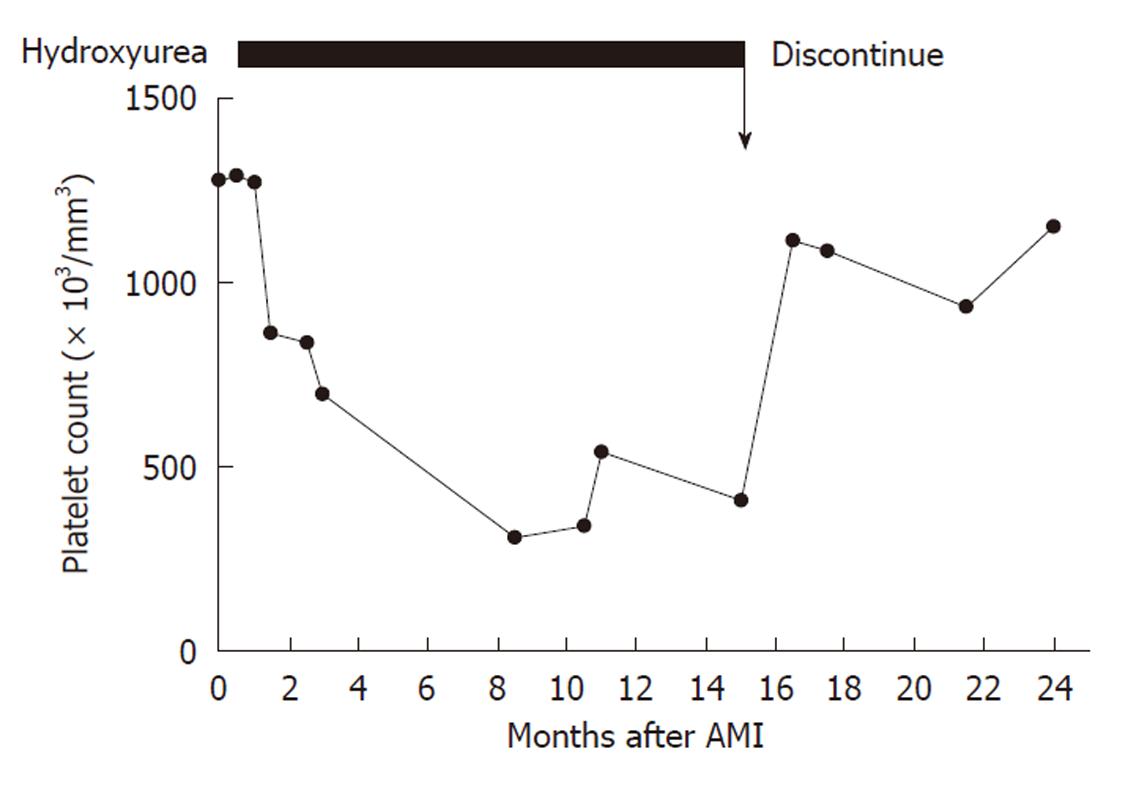

During outpatient clinic follow-up at the cardiology department, she still occasionally experienced chest tightness so the verapamil dosage was increased to 120 mg twice daily 2 wk after discharge. The chest tightness almost disappeared thereafter but recurred twice after she discontinued verapamil of her own accord. The hematologist had prescribed hydroxyurea for 15 mo and the platelet count was decreased to 408 000/mm3 8 mo after discharge (Figure 2). Since the patient had no risk factors for coronary artery disease and ET-related thrombus and coronary artery-related complications due to the prior AMI were less likely, the necessity of ET treatment was questioned by the hematologist. After discussion with the cardiologist, the hydroxyurea was discontinued and the platelet count rose to 1 154 000/mm3 9 mo later. The chest pain did not recur despite the presence of thrombocythemia during the 9 mo follow-up after discontinuation of hydroxyurea.

ET is a clonal myeloproliferative disorder of unknown origin characterized by abnormal megakaryocyte proliferation that frequently causes thrombus formation in the systemic arteries. It is manifested clinically by overproduction of platelets in the absence of a definable cause. The incidence of ET-related thrombotic events was 13%-17.6% and 8.7%-10% at diagnosis and during follow-up, respectively, in Oriental studies[6,7], compared with 15%-26.4% and 11%-31.8% in analogous Western research[8,9]. Although ET may cause systemic vascular thrombosis with subsequent tissue ischemia, involvement of the coronary arteries without stenotic lesions, as determined by coronary angiography, is extremely rare. In reported cases involving ET, AMI and no coronary artery stenosis, most authors[2-5], except Koh et al[10], who have suggested that coronary vasospasm plays a role, have proposed that the AMI is related to an increase in platelet count and aggregability. However, the proposed role for coronary vasospasm was speculative without angiographic confirmation. To our knowledge, coronary vasospasm-related AMI in patients without significant coronary artery stenosis and ET has never been documented before the presented case.

We presumed that the patient’s AMI was due to coronary vasospasm based on the following evidence: (1) the patient had not received thrombolytic therapy; (2) there was no indication of evolutional ST-T changes on the ECG; (3) there was no significant coronary stenosis from coronary angiography on day 3 after admission; and (4) there was no recurrent acute coronary syndrome resulting from thrombocythemia after withdrawal of hydroxyurea. In previous case reports involving ET, AMI and normal coronary arteries, patients underwent coronary angiography 10 d to 3 mo after AMI[3-5]. Even after thrombolytic therapy, it is uncommon not to have significant coronary artery stenosis with a nearly normal coronary artery as determined by coronary angiography 3 d after AMI. Furthermore, the patient initially received antiplatelet and anticoagulation therapy without thrombolysis. Although the infarct-related artery vasospasm was provoked by intra-coronary methylergonovine administration, the possibility of ET-related AMI with a thrombus or thromboembolic material in infarct-related coronary artery could not be excluded. In contrast, thromboxane A2 platelet release increased the tendency for coronary vasospasm. The cytoreductive agent, hydroxyurea, was therefore prescribed by the hematologist during follow-up. Based on the possibility that the AMI would be related to coronary vasospasm instead of ET in a young female without cardiac risk factors and significant coronary artery stenosis, the hydroxyurea was discontinued 15 mo post AMI. In their report of a 49-year-old patient with ET and AMI, Douste-Blazy et al[4], described AMI recurring 2 mo after withdrawal of hydroxyurea. Our presented patient did not experience any recurrent chest discomfort after discontinuation of hydroxyurea for 9 mo, even though her platelet count range was 937 000-1 154 000/mm3. In addition, there were two episodes of chest pain when she discontinued verapamil of her own accord without concomitant discontinuation of the hydroxyurea. From the clinical response point of view, it appears that the coronary vasospasm-related chest pain was controlled by the verapamil not by the decreased platelet count.

The present case report has some limitations. First, the patient did not undergo coronary angiography immediately because we did not have a primary percutaneous coronary intervention team at the time. Second, we did not obtain the 12-lead ECG immediately after sublingual nitroglycerin administered. The ECG on day 2 is less important in the diagnosis of coronary vasospasm.

In summary, the presented case demonstrates that coronary vasospasm is a possible cause of vascular occlusion in patients with ET and no significant coronary artery stenosis.

Peer reviewers: Manel Sabaté, MD, PhD, Chief, Cardiology Department, ClinicUniversityHospital, c/Villarroel 170, 08036 Barcelona, Spain; Matej Podbregar, Professor, Center for intensive care, University Clinical centre Ljubljana, Slovenia, Zaloska c 7, Ljublajna 1000, Slovenia

S- Editor Cheng JX L- Editor Cant MR E- Editor Zheng XM

| 1. | Saffitz JE, Phillips ER, Temesy-Armos PN, Roberts WC. Thrombocytosis and fatal coronary heart disease. Am J Cardiol. 1983;52:651-652. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 2. | Scheffer MG, Michiels JJ, Simoons ML, Roelandt JR. Thrombocythemia and coronary artery disease. Am Heart J. 1991;122:573-576. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 3. | Okayasu N, Murata M, Ueda A, Su KM, Sada T, Ito T, Hasegawa Y, Matsumoto S, Ito Y. Primary thrombocythemia and myocardial infarction in a 26-year-old woman with normal coronary arteriogram. Jpn Heart J. 1981;22:439-445. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 4. | Douste-Blazy P, Taudou MJ, Delay M, Pris J, Sie P, Ribaut L, Galinier F, Bernadet P. Essential thrombocythaemia and recurrent myocardial infarction. Lancet. 1984;2:992. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 5. | Kaya H, Gündogdu M, Tekin SB, Akarsu E, Bozkurt E. Essential thrombocythemia and recurrent myocardial infarction. Clin Lab Haematol. 2000;22:161-162. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 6. | Dan K, Yamada T, Kimura Y, Usui N, Okamoto S, Sugihara T, Takai K, Masuda M, Mori M. Clinical features of polycythemia vera and essential thrombocythemia in Japan: retrospective analysis of a nationwide survey by the Japanese Elderly Leukemia and Lymphoma Study Group. Int J Hematol. 2006;83:443-449. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 38] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Chim CS, Kwong YL, Lie AK, Ma SK, Chan CC, Wong LG, Kho BC, Lee HK, Sim JP, Chan CH. Long-term outcome of 231 patients with essential thrombocythemia: prognostic factors for thrombosis, bleeding, myelofibrosis, and leukemia. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:2651-2658. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 92] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Elliott MA, Tefferi A. Thrombosis and haemorrhage in polycythaemia vera and essential thrombocythaemia. Br J Haematol. 2005;128:275-290. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 329] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 311] [Article Influence: 16.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Wolanskyj AP, Schwager SM, McClure RF, Larson DR, Tefferi A. Essential thrombocythemia beyond the first decade: life expectancy, long-term complication rates, and prognostic factors. Mayo Clin Proc. 2006;81:159-166. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 10. | Koh KK, Cho SK, Kim SS, Oh BH, Lee YW. Coronary vasospasm, multiple coronary thrombosis, unstable angina and essential thrombocytosis. Int J Cardiol. 1993;41:168-170. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |