Abstract

In the past decade, a new field has formed to investigate the concept of mind-wandering, or task-unrelated thought. The state of mind-wandering is typically contrasted with being on-task, or paying attention to the task at hand, and is related to decrements in performance on cognitive tasks. The most widely used method for collecting mind-wandering data—the probe-caught method—involves stopping participants during a task and asking them where their attention is directed. In this review, 145 studies from 105 articles published between 2005 and 2015 were classified according to the framing and wording of the thought probe and response options. Five distinct methodologies were identified: neutral (in which counterbalancing was used to equally emphasize on-task and off-task states), dichotomous (say “yes” or “no” to one thought state), dichotomous (choose between two thought states), categorical, and scale. The review identifies at least 69 different methodological variants, catalogues the verbatim probes and response options used in each study, and suggests important considerations for future empirical work.

Similar content being viewed by others

In the state of flow described by Csikszentmihalyi (1990), both happiness and productivity are maximized. In reality, however, we may not be paying attention to what we are doing some 50% of the time (Seli, Carriere, Levene, & Smilek, 2013). Recently, a field of research has emerged focusing on the concept of “mind-wandering.” The tendency to mind-wander appears to differ both between and within people. For instance, older adults tend to report less mind-wandering than do younger adults (Jackson & Balota, 2012), and we tend to mind-wander more during an easy than during a difficult task (Forster & Lavie, 2009). Since the field of mind-wandering exploded in 2006 (Callard, Smallwood, Golchert, & Margulies, 2013), researchers have looked at various factors, both internal and external, that impact people’s levels of mind-wandering. Because the field has exploded so quickly, though, the methods used to collect mind-wandering reports have not followed a set protocol. In this review, I systematically catalogue the specific methodologies of studies from the past decade that have used the “probe-caught” method for investigating mind-wandering.

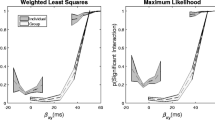

There are, broadly, two approaches to investigating mind-wandering: objective/indirect and subjective/direct (see Fig. 1). The objective/indirect measures are collected through task performance variables, such as reaction times (Cheyne, Carriere, & Smilek, 2006) and eye movements (Reichle, Reineberg, & Schooler, 2010). The subjective/direct measures are self-reports of participants’ own internal states. Although entirely introspective in nature, data from these self-report measures have been found to correlate moderately with performance-related objective measures such as reaction times (Cheyne et al., 2006), and also with physiological measures including eye movements (Reichle et al., 2010). With well over 100 articles since 2006 using this self-report methodology, it has become quite popular.

The method of collecting subjective, self-reported mind-wandering reports can be further divided into two approaches: self-caught and probe-caught. In the self-caught method—much less popular, and not of interest to this review—participants voluntarily indicate, at any moment in time during a task, when their attention has shifted away from that task (Giambra, 1989). This type of mind-wandering requires participants to be aware of their internal state without any prompting (“meta-aware”; Schooler, 2002). Because meta-awareness is often lacking, however, there is seldom a relationship between self-caught mind-wandering and performance in studies of self-caught mind-wandering (Schooler, Reichle, & Halpern, 2004)—a relationship that is commonly found with objective measures of mind-wandering (e.g., Smallwood, Brown, et al., 2011). The method for collecting mind-wandering that is addressed in this review is the probe-caught method. In this procedure, participants are stopped throughout a task and asked to indicate where their attention is focused. Self-reported mind-wandering collected through this method, although subjective, is often found to correlate negatively with performance on both comprehension (Smallwood, McSpadden, & Schooler, 2008) and memory (Risko, Anderson, Sarwal, Engelhardt, & Kingstone, 2012) tests of information encoded while mind-wandering was measured.

Perhaps the most neutral, unbiased method for collecting probe-caught mind-wandering data is the open-ended method, which involves having participants report exactly what they are thinking, verbatim, at each probe (Klinger, 1984). In this way, the researcher can classify the thought reports post-hoc into appropriate categories, such as on-task thoughts and mind-wandering. However, this method has rarely been employed in contemporary research, probably due to practical constraints (recording verbatim thoughts requires individual data collection, and coding the thoughts takes a lot of researcher time); but see Baird, Smallwood, and Schooler (2011) for a recent exception. Most probe-caught research has instead involved presenting participants with a question, probe, or prompt regarding their internal state. This question is usually accompanied by a set of response options, or sometimes a scale that participants use to indicate the extent to which they are on-task versus mind-wandering. This method allows the researchers to obtain a quantitative data point (binary or scale, depending on the response options) at each time point when the mind-wandering probe is presented. As this review demonstrates, however, researchers have not been entirely consistent with respect to how this probe and its accompanying response options are worded.

Background from survey research

Decades of survey research have indicated that heterogeneous question wording and response options can be problematic when trying to draw comparisons between studies; we cannot assume construct equivalence between studies using different methodologies. Unfortunately, although much research has been dedicated to establishing more preferable question and response option wordings, a clear consensus on these decisions has not emerged. However, on the basis of this literature we can identify a number of relevant dimensions on which self-report questions can vary, and we can reflect on how each dimension might affect participants’ responses. First, however, it will be useful to consider how respondents generally approach answering survey questions.

How people answer survey questions

According to Krosnick and Presser (2010), respondents go through a four-step process to answer a survey question. In particular, respondents attempt to (1) understand the question, (2) find relevant information in memory on which to base a response, (3) extract a single answer based on this information, and (4) map that answer onto one of the provided response options (assuming that it is not an open-ended question). Some of these steps are more relevant to mind-wandering probes than are others. Since the same question is repeated multiple times during a typical mind-wandering study, and since participants usually engage in a practice phase in which they encounter the question and response options, the first step of understanding the question does not need to reoccur at each subsequent probe. Next, since participants are being asked about the moments immediately preceding the probe, they will not usually need to—or ought not to—search long-term memory for a response, but instead should rely on their working memory to indicate where their thoughts were immediately prior to the probe. Steps 3 and 4, however, are quite relevant to answering a probe-caught mind-wandering question: Participants will need to label the thoughts they were having that immediately preceded the probe, and then they will have to map those thoughts onto one of the options provided. This step of identifying the appropriate response option will necessarily differ depending on which response options, and how many, are provided.

Heuristics and biases that affect responses

Optimizing versus satisficing

The effort with which respondents perform the four steps described above can be mapped onto a dimension ranging from optimizing (i.e., choosing the most accurate response option) to arbitrary responding. Along this scale, respondents will show some degree of satisficing (Krosnick, 1999), which involves choosing the first response option that seems “good enough” and can occur for a variety of reasons—including both factors related to the task itself (specifically, high task difficulty) and factors inherent to the participants (in particular, low motivation or low ability).

Social desirability responding

Participants—particularly those more likely to want to please the experimenter; for example, older adults—may feel that mind-wandering is undesirable. Thus, one form of satisficing may involve the withholding of off-task thought reports. For this reason, some researchers choose to suppress the term “mind-wandering” from the participant instructions (e.g., Jackson & Balota, 2012) or take care to emphasize that mind-wandering is natural and to be expected (e.g., Nagamatsu, Kam, Liu-Ambrose, Chan, & Handy, 2013). Although this issue is beyond the scope of this review, it would be interesting to examine how different researchers have operationalized mind-wandering in their participant instructions.

Acquiescence bias

One specific form of satisficing involves de facto agreeing with statements; this is known as “acquiescence,” and it is particularly likely when participants are asked yes/no questions such as “Are you mind-wandering?” or “Is your mind on task?” The size of the acquiescence bias observed in any given mind-wandering study is, of course, impossible to determine without a manipulation of the probe itself, but from previous research, we might expect a difference of about 10% (Krosnick & Presser, 2010). Thus, asking “Are you mind-wandering?” could bias participants toward higher rates of self-reported mind-wandering, which would presumably not reflect true differences in actual mind-wandering, relative to when the question is formulated as “Is your mind on task?” (see Weinstein, De Lima, & van der Zee, 2017).

Scales

One way to avoid the acquiescence bias that could occur with binary statements is to give participants a scale on which to report their answers (in the case of mind-wandering, this could involve a scale from “on-task” to “off-task”, or “vice versa”). However, scales are also potentially problematic in a number of ways.

Number of items on ratings scale

The research on the optimal number of response options on a Likert (or other) rating scale is incredibly rich and nuanced. Some studies (e.g., Lissitz & Green, 1975) have shown greater reliability and validity as the number of response options increases up to a certain point, whereas others (e.g., Bendig, 1954) have not shown this relationship. Confusingly, the difficulty of a question may either increase or decrease when the number of response options increases (Krosnick & Presser, 2010). A greater number of response options could lead to a more difficult choice of which option to pick. On the other hand, a smaller number of response options could lead to confusion if none of the provided response options accurately capture the answer the participant wants to volunteer. In mind-wandering research, confusion could be particularly salient in the case of binary response options if participants do not experience their thought state as a binary phenomenon.

Neutral alternatives

Scales also differ in terms of whether they include a middle (neutral) alternative—a scale with an odd number of response options will typically include a neutral alternative, whereas binary question formats and even-numbered scales do not. Including a neutral response option may increase satisficing; in the case of probe-caught mind-wandering, this would manifest itself as picking the neutral/middle option instead of expending effort to determine one’s though state. However, neutral response options have been shown to increase reliability and validity, presumably because they prevent participants from choosing response options at random when they truly do not have a preference for one option over the other (O’Muircheartaigh, Krosnick, & Helic, 2001).

Ordering of scale options

Regardless of the number of response options provided, researchers must pick an order in which the scale options will be displayed (e.g., from completely on task to not at all on task). In general, research has converged on the notion that participants tend to exhibit a primacy effect, skewing their responses to the left of a response scale (e.g., Payne, 1971). Ideally, therefore, counterbalancing would be used to overcome this biasing effect of scale direction (Krosnick & Presser, 2010).

Categorical response options

Instead of a scale from on-task to mind-wandering, researchers may choose to present participants with a set of categories that can be used to describe their thought state. In this situation, a choice has to be made as to the order of the thought categories presented for selection (in theory, this order could also be counterbalanced, but no mind-wandering researchers have chosen to do this). Satisficing will push respondents toward choosing options higher up on the list, because participants may stop evaluating options once they find an option that adequately describes their thought state.

Methodological issues in probe-caught mind-wandering

A handful of studies have begun to address methodological issues in probe-caught mind-wandering research. Evidence is starting to amass regarding the various biases that may apply to this line of inquiry. Vinski and Watter (2012) found that an honesty prime reduced reports of probe-caught mind-wandering, suggesting that demand characteristics may play a role in the high rates of mind-wandering reported in some studies. In addition, priming participants for honesty strengthened the relationship between mind-wandering and performance, suggesting that the effect was not simply one of criterion-setting. In addition, Seli, Jonker, Cheyne, Cortes, and Smilek (2015) found that participants’ confidence in their self-reported attention state (mind-wandering or on-task) was an important moderator of the relationship between mind-wandering and task performance, with low-confidence attentional-state reports correlating less strongly with performance. The finding by Seli, Jonker, et al. that 16% of the responses fell into the low-confidence category suggests that a subset of thought state reports may be made as guesses. These guesses would be most prone to demand characteristics. In addition, Seli, Carriere, Levene, and Smilek (2013) demonstrated that the rate at which probes are presented during a sustained-attention task can drastically affect the rates of reported mind-wandering, with longer interprobe intervals resulting in much greater reported rates of mind-wandering. The authors concluded that this pattern stemmed from response bias and not from a true fluctuation in mind-wandering rates caused by probe frequency, because objective measures they also employed did not fluctuate with probe frequency.

In this review, I have documented the different probe framings and specific wordings of probes and response options used in probe-caught mind-wandering studies published between 2005 and 2015. The goal of this exercise was to provide a comprehensive overview of the different methodological variants that currently exist in the literature for measuring probe-caught mind-wandering.

Method

Criteria

I used three criteria to select studies for inclusion in my review. The first criterion for inclusion was that the researchers must have collected probe-caught mind-wandering data. That is, studies that measured only self-caught mind-wandering, where the participant had to spontaneously indicate a mind-wandering episode (e.g., Grandchamp, Braboszcz, & Delorme, 2014), were not included. The second criterion for inclusion was that the probe must have targeted on-line mind-wandering. That is, participants must have been asked to reflect only on the moments just before the probe when reporting whether they were mind-wandering; studies in which participants were asked to reflect back on a longer period, such as a block of trials, were not included (e.g., Farley, Risko, & Kingstone, 2013; Stawarczyk, Cassol, & D’Argembeau, 2013). Finally, participants must have been forced to classify their mind-wandering (with a binary, category, Likert, or continuous-scale judgment) rather than freely reporting the contents of their thoughts (e.g., Baird et al., 2011). Experience-sampling studies outside the lab (e.g., McVay, Kane, & Kwapil, 2009) were included as long as they involved questions about participants’ current attentional state just prior to the occurence of an experience-sampling probe.

Sources

I gathered peer-reviewed journal articles (excluding published conference proceedings) from three sources. First, I systematically examined every article in the most recent review of mind-wandering, by Smallwood and Schooler (2015). From that review I identified 89 studies across 66 publications. Next, to catch other relevant articles that may have not been cited in the review, I searched Google Scholar for articles with the term “mind-wandering” (also “mind wandering” and “mindwandering”) in the title, published during the period from 2005 to August 2015, when I performed the last search. This search yielded an additional 55 studies across 38 publications. Finally, I looked at all of the articles in the Frontiers Research Topic “Towards a Psychological and Neuroscientific Account of the Wandering Mind,” from which I added one final study (the rest had all been picked up using Methods 1 and 2). The review below thus includes 145 studies reported across 105 journal articles. The “Found in” columns of Tables 1a, 1b, 2a, 2b, 3a, 4a, 4b, 5a, 5b and 6 provide information on the source(s) that included each publication.

Information gathering

After identifying the 145 studies of interest, I next examined the methods used in each study. Two of the studies (Franklin, Mrazek, et al., 2014 [experience sampling], and Stawarczyk, Majerus, Van der Linden, & D’Argembeau, 2012) were excluded because they did not report any new mind-wandering data. Tables 1a, 1b, 2a, 2b, 3a, 4a, 4b, 5a, 5b, and 6 present all of the examined studies, with information regarding the exact wording of the probe and response options. In many cases, details regarding the exacting wording were missing from the publication. To get these details, I contacted the first author of each relevant publication. Information was missing for 52 of the 145 studies; after contacting the authors, I was able to obtain information for all but five of the studies (see Table 10).

Results

I discovered five distinct response option methodologies in use across the studies: neutral (or counterbalanced), dichotomous (“yes/no”), dichotomous (“on-task/mind-wandering”), categorical, and scale. With the exception of the neutral methodology (Tables 1a and 1b) and the unclassifiable studies (Table 6), the remaining four methodologies could be further broken down into those that anchored the participants on-task and those that anchored the participants off-task. Thus, for Tables 2, 3, 4, and 5 versions a and b of each table include the studies that anchored on-task and off-task, respectively.

The breakdown in terms of the number of studies that fell into each type of methodology is presented in Fig. 2. Only one of these five methodologies involved full probe neutrality and/or counterbalancing of response options. A probe was considered neutral if it referenced neither an on-task nor an off-task thought state, such as in the probe “What were you thinking just now?” (Forster & Lavie, 2009, 2014). Furthermore, for the methodology to be truly neutral, counterbalancing of the response options must also have been employed. That is, the order of the response options or the direction of the scale must have been counterbalanced between participants, as in Christoff, Gordon, Smallwood, Smith, and Schooler (2009), in which “subjects answered using a 7-point Likert scale, ranging from ‘completely on task’ to ‘completely off task’…(with the scale direction counterbalanced across subjects)” (p. 8720). Eight studies across six different articles and four different labs met both of these criteria (Christoff et al., 2009; Thomson, Besner, & Smilek, 2013; Thomson, Seli, Besner, & Smilek, 2014; Thomson, Smilek, & Besner, 2014; Ward & Wegner, 2013; Ye, Song, Zhang, & Wang, 2014; see Table 1a). Five additional studies across four different articles and three different labs (Dixon & Bortolussi, 2013, Exp. 1; Dixon & Li, 2013; Killingsworth & Gilbert, 2010) did not counterbalance the order of the response options or the direction of the response scale, but instead the response options were presented in the opposite order from how they had been presented in the probe, making it unclear which of the two states (on-task or off-task) was emphasized (see Table 1b).

The remaining four methods of collecting mind-wandering data were biased to some extent toward one of the two attentional states (on-task or off-task). In some cases, the probe mentioned one of the two attentional states and asked participants to endorse or deny the state by answering either “yes” or “no,” respectively. For example, Deng, Li, and Tang (2014) asked participants, “Did you focus on the task just now?”; analogously, Krawietz, Tamplin, and Radvansky (2012) asked participants, “Are you mind wandering?” However, a comparison of Tables 2a and 2b reveals that the latter—asking participants whether they were off-task—was a much more common methodology than asking participants whether they were on-task; in only two studies were participants asked whether they were on-task (Table 2a), as compared to 29 studies in which participants were asked whether they were mind-wandering (i.e., off-task; Table 2b).

Another very common methodology was to ask participants to choose between two options: on-task or off-task (mind-wandering). Twenty-five studies, summarized in Table 3a, posed the question in this way. It is important to note that the order of the response options (on-task vs. mind-wandering) was consistent across these 25 studies; in not a single study were participants asked whether they were “mind-wandering or on-task” (reversing the order; hence there is no Table 3b). This is interesting when considered alongside the yes/no method described in the previous paragraph, which revealed a strong preference for asking participants whether they were mind-wandering (Table 2b) rather than whether they were on-task (Table 2a).

Another set of studies went beyond the dichotomy of yes/no or on-task/off-task response options, by allowing participants to choose between a set of categorical options to describe their attentional states. There was a great deal of variability in terms of the number and nature of these options. The number of options ranged from three to nine and sometimes referred to the specific nature of the thoughts—for example, temporal context (“past” vs. “future”; Smallwood, Nind, & O’Connor, 2009) or intentionality (INTENTIONALLY MIND WANDERING vs. UNINTENTIONALLY MIND WANDERING; Seli, Cheyne, Xu, Purdon, & Smilek, 2015). In this set of studies, there was once again a strong preference for listing the on-task option first and off-task last: 42 studies listed the on-task option first (Table 4a), whereas only two studies listed mind-wandering first (Table 4b).

The fourth general method involved letting participants respond about their attentional state on a scale from on-task to off-task, or vice versa. These scales usually involved a number of response options, ranging from four to nine, although Macdonald, Mathan, and Yeung (2011) used a continuous vertical scale. In this method, as in the dichotomous and multiple-category methods, the on-task option was once again most commonly used as the anchor: In 25 studies the on-task option was presented to the left of the Likert scale (Table 5a), whereas in only two studies was the opposite the case (Table 5b).

In some cases I was unable to classify the bias of a particular study, because precise information was not available in the article and the authors did not respond to requests for clarification (see Table 6). An example of this is Smallwood, McSpadden, and Schooler (2008), in which the probe read “Just prior to being asked, was your attention on- or off-task?” but the response options, as presented in the article, read “tuning out,” “zoning out,” and “on task”—but it was not clear whether this order or the order in the probe was actually presented to participants.

Another way to look at this data set is to identify the number of unique methodological variants employed by the field. A conservative analysis yielded 69 such variants; Fig. 3 summarizes the proliferation of different methodological variants by plotting their cumulative numbers, as well as the numbers of different articles and of studies within those articles, over time.

Cumulative experiments, articles, and methodological variants by publication year. Note that this is a conservative estimate; in cases in which the response options differed subtly but the methodology was functionally similar, the variants were not separated. An example of this is where participants were asked to choose between “on-task” and “off-task” or between “on-task” and “mind-wandering.” This figure includes only 132 of the 145 studies in this review because insufficient information was provided for 13 of the studies to determine whether a new or existing methodological variant was used

Discussion

What methodological observations can be extracted from this compilation of a decade’s worth of work on probe-caught mind-wandering? Perhaps due to the immense interest in the field of mind-wandering and the speed at which has expanded, with many labs jumping on the bandwagon, there has been no standardization of the probe-caught method for collecting mind-wandering. As a result, there have been almost as many different probes and response options as there have been studies. Within each of the distinct categories I described above, variation in the specific wordings of both probes and response options has been abundant; this is particularly striking in the categorical methodology, in which a wide range of semantic categories have been used for thought classification, depending on the authors’ specific research questions.

Although this methodological heterogeneity ought to be addressed so that the field can reach a consensus on how to measure probe-caught mind-wandering most accurately, it could also be seen as a strength of the field. If the same theoretical conclusions can be drawn from studies that measure mind-wandering in a variety of ways, the conclusions are more likely to be accurate. For example, one recurring phenomenon is the negative correlation between probe-caught mind-wandering and task performance on a sustained-attention task. This relationship has been observed with at least three different probe-caught mind-wandering methodologies—binary (e.g., Seli et al., 2014), categorical (e.g., Seli, Cheyne, et al., 2015), and scale (e.g., Seli et al., 2014). Similarly, mind-wandering during study has also been found to correlate negatively with later memory performance, and this relationship has also been observed when mind-wandering was measured with binary response options (e.g., Risko et al., 2012), categorical response options (e.g., Storm & Bui, 2015), and scales (e.g., Mrazek, Franklin, Phillips, Baird, & Schooler, 2013). The fact that these relationships can be found consistently with a variety of methodologies lends credence to the observed effects.

One striking pattern that can be observed from Fig. 2 is the strong contrast between the binary, yes/no studies (Tables 2a and 2b) and all other methodologies. That is, the vast majority (94%) of the yes/no studies asked participants whether they had been mind-wandering (rather than whether they had been on-task). On the other hand, in the remaining methodologies, in the majority of cases (96%) participants were asked whether they had been on-task, versus in another attentional state. Why might this framing matter? Indeed, as of right now no published data directly address how probe framing affects mind-wandering reports (Weinstein et al., 2017). However, we might look to data from other domains in which framing has been manipulated. Seminal work by Tversky and Kahneman (1981) demonstrated that whether decisions are framed positively (in terms of gains) or negatively (in terms of losses) impacts decision-making. More recently, Finn (2008) extended the framing paradigm to metacognitive judgments of memory, showing that people are less likely to be overconfident when they judge their learning in terms of future forgetting rather than future remembering. In addition, the honesty prime study by Vinsky and Watter (2012) suggests that demand characteristics affect not only the levels of reported mind-wandering, but also the relationship between mind-wandering and accuracy measures.

Recommendations

On the basis of this review, I have three broad recommendations: (1) Those intending to conduct probe-caught mind-wandering studies should familiarize themselves with the different methodological variants already employed in the past decade (see Tables 1a, 1b, 2a, 2b, 3a, 4a, 4d, 5a, 5b and 6) and make an informed choice for their own experiments; (2) when making these decisions, mind-wandering researchers should also acquaint themselves with relevant survey research literature (e.g., Krosnick & Presser, 2010) and follow the recommendations from that literature, as detailed below; and (3) further research should attempt to determine whether framing effects are a concern in the probe-caught mind-wandering paradigm (Weinstein et al., 2017).

In addition to these broad recommendations, more specific recommendations can be made on the basis of the survey research discussed earlier in this article. Mind-wandering researchers should be aware that the following potential sources of bias could arise from their choice of methodology:

-

1.

Binary yes/no probes may lead to acquiescence, such that participants will tend to default to a “yes” response (Krosnick & Presser, 2010). In fact, in a forthcoming article (Weinstein et al., 2017) we show that simply changing the mind-wandering probe from “At the time of the ding, my mind was on the text” to “At the time of the ding, my mind was on something other than the text” increased mind-wandering reports by 10%.

-

2.

If a scale is used, researchers should think carefully about the number of options provided: Having too few response options can encourage random responding, because participants will not find an option that accurately reflects their desired answer, whereas an overabundance of response options can make the task too difficult (Krosnick & Presser, 2010).

-

3.

The order of options on a given scale should ideally be counterbalanced between participants (e.g., as in Christoff et al., 2009) to prevent anchoring (Payne, 1971) to the leftmost option.

-

4.

If categorical response options are used, they should not be too numerous, and they also ought to be counterbalanced to avoid order effects.

-

5.

Researchers should be particularly careful when conducting probe-caught mind-wandering research with vulnerable populations, including older adult, children, and participants with lower ability, who may be more prone to satisficing (Krosnick, Narayan, & Smith, 1996), especially in combination with fatigue (Clancy & Wachsler, 1971).

-

6.

Be aware that social desirability may push participants to report on-task thoughts more or less often, depending on whether mind-wandering is presented as being positive or negative (Parry & Crossley, 1950).

Conclusion

In the present review I identified, by a conservative estimate (see Fig. 3), 69 different methodological variants of probe-caught mind-wandering among 145 studies. In other words, almost one in every two new studies has used probe or response option wordings that have never been reported in the literature. Moreover, this methodological review has focused only on the probe and response option wordings; further differences would have emerged if I had taken into account the ways that mind-wandering was defined for participants. The lack of methodological consensus in this field may have emerged in part due to a lack of open communication between researchers in terms of their methodological choices. Hopefully the present review will enable mind-wandering researchers to make more informed choices about how they measure probe-caught mind-wandering.

References

* indicates an article included in the methodological review

*Al-Balushi, S. M., & Al-Harthy, I. S. (2015). Students’ mind wandering in macroscopic and submicroscopic textual narrations and its relationship with their reading comprehension. Chemistry Education Research and Practice, 16, 680–688.

*Allen, M., Smallwood, J., Christensen, J., Gramm, D., Rasmussen, B., Jensen, C. G.,…Lutz, A. (2013). The balanced mind: The variability of task-unrelated thoughts predicts error monitoring. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 7, 743. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2013.00743

Baird, B., Smallwood, J., & Schooler, J. W. (2011). Back to the future: Autobiographical planning and the functionality of mind-wandering. Consciousness and Cognition, 20, 1604–1611. doi:10.1016/j.concog.2011.08.007

*Baird, B., Smallwood, J., Fishman, D. J., Mrazek, M. D., & Schooler, J. W. (2013). Unnoticed intrusions: Dissociations of meta-consciousness in thought suppression. Consciousness and Cognition, 22, 1003–1012. doi:10.1016/j.concog.2013.06.009

*Baird, B., Smallwood, J., Lutz, A., & Schooler, J. W. (2014). The decoupled mind: Mind-wandering disrupts cortical phase-locking to perceptual events. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 26, 2596–2607.

*Bastian, M., & Sackur, J. (2013). Mind wandering at the fingertips: Automatic parsing of subjective states based on response time variability. Frontiers in Psychology, 4, 573. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00573

Bendig, A. W. (1954). Reliability and the number of rating scale categories. Journal of Applied Psychology, 38, 38–40.

*Bernhardt, B. C., Smallwood, J., Tusche, A., Ruby, F. J., Engen, H. G., Steinbeis, N., & Singer, T. (2014). Medial prefrontal and anterior cingulate cortical thickness predicts shared individual differences in self-generated thought and temporal discounting. NeuroImage, 90, 290–297.

*Broadway, J. M., Franklin, M. S., & Schooler, J. W. (2015). Early event-related brain potentials and hemispheric asymmetries reveal mind-wandering while reading and predict comprehension. Biological Psychology, 107, 31–43.

Callard, F., Smallwood, J., Golchert, J., & Margulies, D. S. (2013). The era of the wandering mind? Twenty-first century research on self-generated mental activity. Frontiers in Psychology, 4, 891. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00891

*Casner, S. M., & Schooler, J. W. (2013). Thoughts in flight: Automation use and pilots’ task-related and task-unrelated thought. Human Factors, 56, 433–442.

Cheyne, J. A., Carriere, J. S., & Smilek, D. (2006). Absent-mindedness: Lapses of conscious awareness and everyday cognitive failures. Consciousness and Cognition, 15, 578–592. doi:10.1016/j.concog.2005.11.009

*Christoff, K., Gordon, A. M., Smallwood, J., Smith, R., & Schooler, J. W. (2009). Experience sampling during fMRI reveals default network and executive system contributions to mind wandering. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 106, 8719–8724. doi:10.1073/pnas.0900234106

Clancy, K. J., & Wachsler, R. A. (1971). Positional effects in shared-cost surveys. Public Opinion Quarterly, 35, 258–265.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1990). Flow: The psychology of optimal experience. New York, NY: Harper & Row.

*Deng, Y. Q., Li, S., & Tang, Y. Y. (2014). The relationship between wandering mind, depression and mindfulness. Mindfulness, 5, 124–128.

*Dixon, P., & Bortolussi, M. (2013). Construction, integration, and mind wandering in reading. Canadian Journal of Experimental Psychology, 67, 1–10. doi:10.1037/a0031234

*Dixon, P., & Li, H. (2013). Mind wandering in text comprehension under dual-task conditions. Frontiers in Psychology, 4, 682. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00682

Farley, J., Risko, E. F., & Kingstone, A. (2013). Everyday attention and lecture retention: The effects of time, fidgeting, and mind wandering. Frontiers in Psychology, 4, 619. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00619

*Feng, S., D’Mello, S., & Graesser, A. C. (2013). Mind wandering while reading easy and difficult texts. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 20, 586–592.

Finn, B. (2008). Framing effects on metacognitive monitoring and control. Memory & Cognition, 36, 813–821. doi:10.3758/MC.36.4.813

*Forster, S., & Lavie, N. (2009). Harnessing the wandering mind: The role of perceptual load. Cognition, 111, 345–355. doi:10.1016/j.cognition.2009.02.006

*Forster, S., & Lavie, N. (2014). Distracted by your mind? Individual differences in distractibility predict mind wandering. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 40, 251–260.

*Foulsham, T., Farley, J., & Kingstone, A. (2013). Mind wandering in sentence reading: Decoupling the link between mind and eye. Canadian Journal of Experimental Psychology, 67, 51–59.

*Frank, D. J., Nara, B., Zavagnin, M., Touron, D. R., & Kane, M. J. (2015). Validating older adults’ reports of less mind-wandering: An examination of eye movements and dispositional influences. Psychology and Aging, 30, 266–278.

*Franklin, M. S., Smallwood, J., & Schooler, J. W. (2011). Catching the mind in flight: Using behavioral indices to detect mindless reading in real time. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 18, 992–997. doi:10.3758/s13423-011-0109-6

*Franklin, M. S., Broadway, J. M., Mrazek, M. D., Smallwood, J., & Schooler, J. W. (2013). Window to the wandering mind: Pupillometry of spontaneous thought while reading. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 66, 2289–2294.

*Franklin, M. S., Mrazek, M. D., Anderson, C. L., Smallwood, J., Kingstone, A., & Schooler, J. W. (2013). The silver lining of a mind in the clouds: Interesting musings are associated with positive mood while mind-wandering. Frontiers in Psychology, 4.

*Franklin, M. S., Mooneyham, B. W., Baird, B., & Schooler, J. W. (2014). Thinking one thing, saying another: The behavioral correlates of mind-wandering while reading aloud. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 21, 205–210.

*Franklin, M. S., Mrazek, M. D., Anderson, C. L., Johnston, C., Smallwood, J., Kingstone, A., & Schooler, J. W. (2014). Tracking distraction: The relationship between mind-wandering, meta-awareness, and ADHD symptomatology. Journal of Attention Disorders, 21, 475–486. doi:10.1177/1087054714543494

*Franklin, M. S., Smallwood, J., Zedelius, C. M., Broadway, J. M., & Schooler, J. W. (2016). Unaware yet reliant on attention: Experience sampling reveals that mind-wandering impedes implicit learning. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 23, 223–229.

Giambra, L. M. (1989). Task-unrelated thought frequency as a function of age: A laboratory study. Psychology and Aging, 4, 136–143.

Grandchamp, R., Braboszcz, C., & Delorme, A. (2014). Oculometric variations during mind wandering. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, 31. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00031

*Hu, N. T., He, S., & Xu, B. H. (2012). Different efficiencies of attentional orienting in different wandering minds. Consciousness and Cognition, 21, 139–148. doi:10.1016/j.concog.2011.12.007

*Iijima, Y., & Tanno, Y. (2012). The effect of cognitive load on the temporal focus of mind wandering. Shinrigaku Kenkyu: The Japanese Journal of Psychology, 83, 232–236.

*Jackson, J. D., & Balota, D. A. (2012). Mind-wandering in younger and older adults: Converging evidence from the Sustained Attention to Response Task and reading for comprehension. Psychology and Aging, 27, 106–119.

*Jackson, J. D., Weinstein, Y., & Balota, D. A. (2013). Can mind-wandering be timeless? Atemporal focus and aging in mind-wandering paradigms. Frontiers in Psychology, 4, 742. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00742

*Kam, J. W., & Handy, T. C. (2014). Differential recruitment of executive resources during mind wandering. Consciousness and Cognition, 26, 51–63.

*Kam, J. W. Y., Dao, E., Farley, J., Fitzpatrick, K., Smallwood, J., Schooler, J. W., & Handy, T. C. (2011). Slow fluctuations in attentional control of sensory cortex. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 23, 460–470. doi:10.1162/jocn.2010.21443

*Kam, J. W., Dao, E., Blinn, P., Krigolson, O. E., Boyd, L. A., & Handy, T. C. (2012). Mind wandering and motor control: Off-task thinking disrupts the online adjustment of behavior. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 6, 329. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2012.00329

*Kam, J. W. Y., Nagamatsu, L. S., & Handy, T. C. (2014). Visual asymmetry revisited: Mind wandering preferentially disrupts processing in the left visual field. Brain and Cognition, 92, 32–38.

*Kam, J. W. Y., Xu, J., & Handy, T. C. (2014). I don’t feel your pain (as much): The desensitizing effect of mind wandering on the perception of others’ discomfort. Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience, 14, 286–296. doi:10.3758/s13415-013-0197-z

*Kam, J. W. Y., Mickleborough, M. J., Eades, C., & Handy, T. C. (2015). Migraine and attention to visual events during mind wandering. Experimental Brain Research, 233, 1503–1510.

*Kane, M. J., Brown, L. H., McVay, J. C., Silvia, P. J., Myin-Germeys, I., & Kwapil, T. R. (2007). For whom the mind wanders, and when: An experience-sampling study of working memory and executive control in daily life. Psychological Science, 18, 614–621.

*Killingsworth, M. A., & Gilbert, D. T. (2010). A wandering mind is an unhappy mind. Science, 330, 932.

Klinger, E. (1984). A consciousness-sampling analysis of test anxiety and performance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 47, 1376–1390.

*Krawietz, S. A., Tamplin, A. K., & Radvansky, G. A. (2012). Aging and mind wandering during text comprehension. Psychology and Aging, 27, 951–958.

Krosnick, J. A. (1999). Survey research. Annual Review of Psychology, 50, 537–567. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.50.1.537

Krosnick, J. A., & Presser, S. (2010). Questionnaire design. In J. D. Wright & P. V. Marsden (Eds.), Handbook of survey research (2nd ed.). West Yorkshire, England: Emerald Group.

Krosnick, J. A., Narayan, S., & Smith, W. R. (1996). Satisficing in surveys: Initial evidence. New Directions for Program Evaluation, 70, 29–44.

*Kucyi, A., Salomons, T. V., & Davis, K. D. (2013). Mind wandering away from pain dynamically engages antinociceptive and default mode brain networks. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 110, 18692–18697.

*Levinson, D. B., Smallwood, J., & Davidson, R. J. (2012). The persistence of thought evidence for a role of working memory in the maintenance of task-unrelated thinking. Psychological Science, 23, 375–380.

Lissitz, R. W., & Green, S. B. (1975). Effect of the number of scale points on reliability: A Monte Carlo approach. Journal of Applied Psychology, 60, 10–13.

*Macdonald, J. S. P., Mathan, S., & Yeung, N. (2011). Trial-by-trial variations in subjective attentional state are reflected in ongoing prestimulus EEG alpha oscillations. Frontiers in Perception Science, 2, 82. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2011.00082

*Mason, M. F., Norton, M. I., Van Horn, J. D., Wegner, D. M., Grafton, S. T., & Macrae, C. N. (2007). Wandering minds: The default network and stimulus-independent thought. Science, 315, 393–395.

*McKiernan, K. A., D’Angelo, B. R., Kaufman, J. N., & Binder, J. R. (2006). Interrupting the “stream of consciousness”: An fMRI investigation. NeuroImage, 29, 1185–1191.

*McVay, J. C., & Kane, M. J. (2009). Conducting the train of thought: Working memory capacity, goal neglect, and mind wandering in an executive-control task. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 35, 196–204. doi:10.1037/a0014104

*McVay, J. C., & Kane, M. J. (2012a). Drifting from slow to “d’oh!”: Working memory capacity and mind wandering predict extreme reaction times and executive control errors. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 38, 525–549.

*McVay, J. C., & Kane, M. J. (2012b). Why does working memory capacity predict variation in reading comprehension? On the influence of mind wandering and executive attention. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 141, 302–320.

*McVay, J. C., & Kane, M. J. (2013). Dispatching the wandering mind? Toward a laboratory method for cuing “spontaneous” off-task thought. Frontiers in Psychology, 4, 570. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00570

*McVay, J. C., Kane, M. J., & Kwapil, T. R. (2009). Tracking the train of thought from the laboratory into everyday life: An experience-sampling study of mind wandering across controlled and ecological contexts. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 16, 857–863.

*McVay, J. C., Meier, M. E., Touron, D. R., & Kane, M. J. (2013). Aging ebbs the flow of thought: Adult age differences in mind wandering, executive control, and self-evaluation. Acta Psychologica, 142, 136–147.

*Mittner, M., Boekel, W., Tucker, A. M., Turner, B. M., Heathcote, A., & Forstmann, B. U. (2014). When the brain takes a break: A model-based analysis of mind wandering. Journal of Neuroscience, 34, 16286–16295.

*Morrison, A. B., Goolsarran, M., Rogers, S. L., & Jha, A. P. (2014). Taming a wandering attention: Short-form mindfulness training in student cohorts. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 7, 897. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2013.00897

*Mrazek, M. D., Chin, J. M., Schmader, T., Hartson, K. A., Smallwood, J., & Schooler, J. W. (2011). Threatened to distraction: Mind-wandering as a consequence of stereotype threat. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 47, 1243–1248.

*Mrazek, M. D., Smallwood, J., & Schooler, J. W. (2012). Mindfulness and mind-wandering: Finding convergence through opposing constructs. Emotion, 12, 442–448. doi:10.1037/a0026678

*Mrazek, M. D., Smallwood, J., Franklin, M. S., Chin, J. M., Baird, B., & Schooler, J. W. (2012). The role of mind-wandering in measurements of general aptitude. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 141, 788–798. doi:10.1037/a0027968

*Mrazek, M. D., Franklin, M. S., Phillips, D. T., Baird, B., & Schooler, J. W. (2013). Mindfulness training improves working memory capacity and GRE performance while reducing mind wandering. Psychological Science, 24, 776–781.

*Mrazek, M. D., Phillips, D. T., Franklin, M. S., Broadway, J. M., & Schooler, J. W. (2013). Young and restless: Validation of the Mind-Wandering Questionnaire (MWQ) reveals disruptive impact of mind-wandering for youth. Frontiers in Psychology, 4, 560. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00560

*Nagamatsu, L. S., Kam, J. W., Liu-Ambrose, T., Chan, A., & Handy, T. C. (2013). Mind-wandering and falls risk in older adults. Psychology and Aging, 28, 685–691.

O’Muircheartaigh, C. A., Krosnick, J. A., & Helic, A. (2001). Middle alternatives, acquiescence, and the quality of questionnaire data. Irving B. Harris Graduate School of Public Policy Studies, University of Chicago.

*Ottaviani, C., & Couyoumdjian, A. (2013). Pros and cons of a wandering mind: A prospective study. Frontiers in Psychology, 4, 524. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00524

*Ottaviani, C., Shapiro, D., & Couyoumdjian, A. (2013). Flexibility as the key for somatic health: From mind wandering to perseverative cognition. Biological Psychology, 94, 38–43.

*Ottaviani, C., Shahabi, L., Tarvainen, M., Cook, I., Abrams, M., & Shapiro, D. (2015). Cognitive, behavioral, and autonomic correlates of mind wandering and perseverative cognition in major depression. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 8, 433. doi:10.3389/fnins.2014.00433

Parry, H. J., & Crossley, H. M. (1950). Validity of responses to survey questions. Public Opinion Quarterly, 14, 61–80.

Payne, J. D. (1971). The effects of reversing the order of verbal rating scales in a postal survey. Journal of the Marketing Research Society, 14, 30–44.

*Poerio, G. L., Totterdell, P., & Miles, E. (2013). Mind-wandering and negative mood: Does one thing really lead to another? Consciousness and Cognition, 22, 1412–1421. doi:10.1016/j.concog.2013.09.012

*Qin, J., Perdoni, C., & He, B. (2011). Dissociation of subjectively reported and behaviorally indexed mind wandering by EEG rhythmic activity. PLoS ONE, 6, e23124. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0023124

*Reichle, E. D., Reineberg, A. E., & Schooler, J. W. (2010). Eye movements during mindless reading. Psychological Science, 21, 1300–1310.

*Risko, E. F., Anderson, N., Sarwal, A., Engelhardt, M., & Kingstone, A. (2012). Everyday attention: Variation in mind wandering and memory in a lecture. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 26, 234–242.

*Risko, E. F., Buchanan, D., Medimorec, S., & Kingstone, A. (2013). Everyday attention: Mind wandering and computer use during lectures. Computers and Education, 68, 275–283.

*Ruby, F. J., Smallwood, J., Engen, H., & Singer, T. (2013). How self-generated thought shapes mood. PLoS ONE, 8, e77554. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0077554

*Ruby, F. J., Smallwood, J., Sackur, J., & Singer, T. (2013). Is self-generated thought a means of social problem solving? Frontiers in Psychology, 4, 962. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00962

*Rummel, J., & Boywitt, C. D. (2014). Controlling the stream of thought: Working memory capacity predicts adjustment of mind-wandering to situational demands. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 21, 1309–1315.

*Sayette, M. A., Reichle, E. D., & Schooler, J. W. (2009). Lost in the sauce: The effects of alcohol on mind wandering. Psychological Science, 20, 747–752. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02351.x

*Sayette, M. A., Schooler, J. W., & Reichle, E. D. (2010). Out for a Smoke: The impact of cigarette craving on zoning out during reading. Psychological Science, 21, 26–30.

Schooler, J. W. (2002). Re-representing consciousness: Dissociations between experience and meta-consciousness. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 6, 339–344. doi:10.1016/S1364-6613(02)01949-6

Schooler, J. W., Reichle, E. D., & Halpern, D. V. (2004). Zoning-out while reading: Evidence for dissociations between experience and meta-consciousness. In D. T. Levin (Ed.), Thinking and seeing: Visual metacognition in adults and children (pp. 203–226). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

*Seli, P., Carriere, J. S., Levene, M., & Smilek, D. (2013). How few and far between? Examining the effects of probe rate on self-reported mind wandering. Frontiers in Psychology, 4, 430. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00430

*Seli, P., Cheyne, J. A., & Smilek, D. (2013). Wandering minds and wavering rhythms: Linking mind wandering and behavioral variability. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 39, 1–5. doi:10.1037/a0030954

*Seli, P., Carriere, J. S., Thomson, D. R., Cheyne, J. A., Martens, K. A. E., & Smilek, D. (2014). Restless mind, restless body. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 40, 660–668. doi:10.1037/a0035260

*Seli, P., Cheyne, J. A., Xu, M., Purdon, C., & Smilek, D. (2015). Motivation, intentionality, and mind wandering: Implications for assessments of task-unrelated thought. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 41, 1417–1425. doi:10.1037/xlm0000116

*Seli, P., Jonker, T. R., Cheyne, J. A., Cortes, K., & Smilek, D. (2015). Can research participants comment authoritatively on the validity of their self-reports of mind wandering and task engagement? Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 41, 703–709.

*Smallwood, J., & O’Connor, R. C. (2011). Imprisoned by the past: Unhappy moods lead to a retrospective bias to mind wandering. Cognition and Emotion, 25, 1481–1490.

Smallwood, J., & Schooler, J. W. (2015). The science of mind wandering: Empirically navigating the stream of consciousness. Annual Review of Psychology, 66, 487–518.

*Smallwood, J., McSpadden, M., & Schooler, J. W. (2007). The lights are on but no one’s home: Meta-awareness and the decoupling of attention when the mind wanders. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 14, 527–533. doi:10.3758/BF03194102

*Smallwood, J., Beach, E., Schooler, J. W., & Handy, T. C. (2008). Going AWOL in the brain: Mind wandering reduces cortical analysis of external events. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 20, 458–469.

*Smallwood, J., McSpadden, M., Luus, B., & Schooler, J. (2008). Segmenting the stream of consciousness: The psychological correlates of temporal structures in the time series data of a continuous performance task. Brain and Cognition, 66, 50–56.

*Smallwood, J., McSpadden, M., & Schooler, J. W. (2008). When attention matters: The curious incident of the wandering mind. Memory & Cognition, 36, 1144–1150. doi:10.3758/MC.36.6.1144

*Smallwood, J., Nind, L., & O’Connor, R. C. (2009). When is your head at? An exploration of the factors associated with the temporal focus of the wandering mind. Consciousness and Cognition, 18, 118–125.

*Smallwood, J., Brown, K. S., Tipper, C., Giesbrecht, B., Franklin, M. S., Mrazek, M. D.,…Schooler, J. W. (2011). Pupillometric evidence for the decoupling of attention from perceptual input during offline thought. PLoS ONE, 6, e18298. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0018298

*Smallwood, J., Schooler, J. W., Turk, D. J., Cunningham, S. J., Burns, P., & Macrae, C. N. (2011). Self-reflection and the temporal focus of the wandering mind. Consciousness and Cognition, 20, 1120–1126.

*Smallwood, J., Gorgolewski, K. J., Golchert, J., Ruby, F. J., Engen, H., Baird, B.,…Margulies, D. S. (2013). The default modes of reading: Modulation of posterior cingulate and medial prefrontal cortex connectivity associated with comprehension and task focus while reading. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 7, 734. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2013.00734

*Smallwood, J., Ruby, F. J., & Singer, T. (2013). Letting go of the present: Mind-wandering is associated with reduced delay discounting. Consciousness and Cognition, 22, 1–7. doi:10.1016/j.concog.2012.10.007

*Smilek, D., Carriere, J. S., & Cheyne, J. A. (2010). Out of mind, out of sight: Eye blinking as indicator and embodiment of mind wandering. Psychological Science, 21, 786–789.

*Song, X., & Wang, X. (2012). Mind wandering in Chinese daily lives—An experience sampling study. PLoS ONE, 7, e44423. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0044423

*Sousa, T. L. V., Carriere, J. S., & Smilek, D. (2013). The way we encounter reading material influences how frequently we mind wander. Frontiers in Psychology, 4, 892. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00892

*Stawarczyk, D., Majerus, S., Maj, M., Van der Linden, M., & D’Argembeau, A. (2011). Mind-wandering: Phenomenology and function as assessed with a novel experience sampling method. Acta Psychologica, 136, 370–381.

*Stawarczyk, D., Majerus, S., Maquet, P., & D’Argembeau, A. (2011). Neural correlates of ongoing conscious experience: Both task-unrelatedness and stimulus-independence are related to default network activity. PLoS ONE, 6, e16997. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0016997

Stawarczyk, D., Majerus, S., Van der Linden, M., & D’Argembeau, A. (2012). Using the Daydreaming Frequency Scale to investigate the relationships between mind-wandering, psychological well-being, and present-moment awareness. Frontiers in Psychology, 3, 363. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2012.00363

*Stawarczyk, D., Majerus, S., & D’Argembeau, A. (2013). Concern-induced negative affect is associated with the occurrence and content of mind-wandering. Consciousness and Cognition, 22, 442–448.

Stawarczyk, D., Cassol, H., & D’Argembeau, A. (2013). Phenomenology of future-oriented mind-wandering episodes. Frontiers in Psychology, 4, 425. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00425

*Stawarczyk, D., Majerus, S., Catale, C., & D’Argembeau, A. (2014). Relationships between mind-wandering and attentional control abilities in young adults and adolescents. Acta Psychologica, 148, 25–36.

*Storm, B. C., & Bui, D. C. (2016). Individual differences in mind wandering while reading predict lower rates of analogical transfer. Learning and Individual Differences, 51, 427–432. doi:10.1016/j.lindif.2015.02.001

*Szpunar, K. K., Khan, N. Y., & Schacter, D. L. (2013). Interpolated memory tests reduce mind wandering and improve learning of online lectures. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 110, 6313–6317.

*Thomson, D. R., Besner, D., & Smilek, D. (2013). In pursuit of off-task thought: Mind wandering–performance trade-offs while reading aloud and color naming. Frontiers in Psychology, 4, 360. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00360

*Thomson, D. R., Seli, P., Besner, D., & Smilek, D. (2014). On the link between mind wandering and task performance over time. Consciousness and Cognition, 27, 14–26.

*Thomson, D. R., Smilek, D., & Besner, D. (2014). On the asymmetric effects of mind-wandering on levels of processing at encoding and retrieval. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 21, 728–733. doi:10.3758/s13423-013-0526-9

Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1981). The framing of decisions and the psychology of choice. Science, 211, 453–458. doi:10.1126/science.7455683

*Unsworth, N., & McMillan, B. D. (2013). Mind wandering and reading comprehension: Examining the roles of working memory capacity, interest, motivation, and topic experience. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 39, 832–842.

*Unsworth, N., & McMillan, B. D. (2014). Similarities and differences between mind-wandering and external distraction: A latent variable analysis of lapses of attention and their relation to cognitive abilities. Acta Psychologica, 150, 14–25.

*Uzzaman, S., & Joordens, S. (2011). The eyes know what you are thinking: Eye movements as an objective measure of mind wandering. Consciousness and Cognition, 20, 1882–1886.

*Vinski, M. T., & Watter, S. (2012). Priming honesty reduces subjective bias in self-report measures of mind wandering. Consciousness and Cognition, 21, 451–455.

*Vinski, M. T., & Watter, S. (2013). Being a grump only makes things worse: A transactional account of acute stress on mind wandering. Frontiers in Psychology, 4, 730. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00730

*Ward, A. F., & Wegner, D. M. (2013). Mind-blanking: When the mind goes away. Frontiers in Psychology, 4, 650. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00650

Weinstein, Y., De Lima, H. J., & van der Zee, T. (2017). Are you mind-wandering, or is your mind on task? The effect of probe framing on mind-wandering reports. Psychonomic Bulletin and Review (Online First). doi:10.3758/s13423-017-1322-8

*Yanko, M. R., & Spalek, T. M. (2013). Route familiarity breeds inattention: A driving simulator study. Accident Analysis and Prevention, 57, 80–86.

*Ye, Q., Song, X., Zhang, Y., & Wang, Q. (2014). Children’s mental time travel during mind wandering. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, 927. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00927

*Zedelius, C. M., Broadway, J. M., & Schooler, J. W. (2015). Motivating meta-awareness of mind wandering: A way to catch the mind in flight? Consciousness and Cognition, 36, 44–53.

*Zhang, Y., Song, X., Ye, Q., & Wang, Q. (2015). Children with positive attitudes towards mind-wandering provide invalid subjective reports of mind-wandering during an experimental task. Consciousness and Cognition, 35, 136–142. doi:10.1016/j.concog.2015.05.006

Author note

Henry J. De Lima, Kelsey Gilbert, and Sean McCaffery helped locate references and extract methodological details. Nicholas Tilton checked all tables for accuracy. The work was partially supported by a University of Massachusetts–Lowell internal seed grant.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Weinstein, Y. Mind-wandering, how do I measure thee with probes? Let me count the ways. Behav Res 50, 642–661 (2018). https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-017-0891-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-017-0891-9