Abstract

Researchers have recently demonstrated that mind-wandering episodes can vary on numerous dimensions, and it has been suggested that assessing these dimensions will play an important role in our understanding of mind wandering. One dimension that has received considerable attention in recent work is the intentionality of mind wandering. Although it has been claimed that indexing the intentionality of mind wandering will be necessary if researchers are to obtain a coherent understanding of the wandering mind, one concern is that this dimension might be redundant with another, longstanding, dimension: namely, meta-awareness. Thus, the utility of the argument for assessing intentionality rests upon a demonstration that this dimension is distinct from the meta-awareness dimension. To shed light on this issue, across two studies we compared and contrasted these dimensions to determine whether they are redundant or distinct. In both studies, we found support for the view that these dimensions are distinct.

Similar content being viewed by others

Mind wandering – the inward focusing of one’s attention – is a common feature of human experience. In the present article, we focus on two important dimensions of mind wandering: intentionality (i.e., whether it is engaged with intention) and meta-awareness (i.e., whether an individual is aware of its occurrence). Although the meta-awareness dimension has long played a pivotal role in theoretical accounts of mind wandering (Schooler, 2002), only recently have researchers begun to focus more prominently on the theoretical importance of the intentionality dimension (Carriere, Seli, & Smilek, 2013; Forster & Lavie, 2009; Seli, Cheyne, Xu, Purdon, & Smilek, 2015; Seli, Risko, & Smilek, 2016b; Seli, Risko, Smilek, & Schacter, 2016; Seli, Wammes, Risko, & Smilek, 2015). However, at face value, the dimensions of intentionality and meta-awareness appear to share considerable overlap, and there remains the possibility that they may even be completely redundant. If this were the case, then it would suggest – contrary to recent claims (Seli, Risko, & Smilek, 2016b; Seli et al., 2016) – that researchers ought not to concern themselves with the intentionality dimension of mind wandering because it would provide no unique information beyond the meta-awareness dimension. If, on the other hand, there were evidence to suggest that these two dimensions are distinct, then this would provide support for the view that both dimensions ought to be considered in theoretical accounts of the wandering mind. To shed light on this important issue, here we present two studies in which we compared and contrasted the intentionality and meta-awareness dimensions of mind wandering to determine whether they are redundant or distinct.

The level of awareness of mind wandering

Although we are, by definition, aware of our conscious experiences, there is evidence to suggest that we sometimes have conscious experiences in the absence of explicit consideration of what we are attending to (e.g., Reichle, Reineberg, & Schooler, 2010; Schooler, 2002; Schooler et al., 2011; Zedelius, Broadway, & Schooler, 2015). For example, consider the scenario in which you are reading, but your attention has wandered from your task. Although you are aware of the contents of your mind wandering, you nevertheless fail to recognize that your attention has wandered from the text, and this lack of awareness is evidenced by the fact that you continue to scan the page without processing the material being scanned. On the basis of this and other similar situations in which different “levels” or “states” of consciousness are apparent, Schooler (2002) proposed a distinction between “basic consciousness” and “meta-consciousness.” Basic consciousness, which is defined as cognitive processing that includes “perceptions, feelings, and non-reflective cognitions” (Schooler, 2002; p. 341), is said to be a continuous process that occurs throughout our waking hours. Meta-consciousness, on the other hand, is said to be a “monitoring system” that is engaged intermittently to evaluate the contents of basic consciousness and to consider the relation of such contents to the goals of the individual. According to Schooler (2002), it is meta-consciousness (or “meta-awareness”) that allows an individual to become aware of periods of mind wandering.

To empirically demonstrate that people do in fact mind-wander in the absence of their awareness of being in a state of mind wandering, Schooler, Reichle, and Halpern (2004) conducted a study in which participants read passages of text while monitoring their mental states so that they could report any mind wandering that they experienced (i.e., they were instructed to “self-catch” their mind wandering while reading). In addition to self-catching mind wandering, participants were presented with intermittent “thought probes” that asked them to report whether they were mind wandering just prior to the presentation of the probes. Schooler et al. found that, although participants often caught themselves mind wandering while reading, they nevertheless sometimes also reported mind wandering when presented with a probe. If participants were always aware of their mind wandering, then rather than being caught by the probe, they would have first self-caught their mind wandering, reported it, and presumably returned their focus back on the task prior to the presentation of the probe. Given that this was not the case (since the probe sometimes caught people mind wandering), this finding was taken as evidence to suggest that people sometimes mind-wander while being completely unaware that they are doing so.

Building on the distinction made between basic consciousness and meta-awareness, Smallwood, McSpadden, and Schooler (2007) went on to propose two states of mind wandering that vary as a function of whether meta-awareness is engaged. Specifically, they coined the terms: “tune-outs” and “zone outs,” which reflect mind wandering with and without meta-awareness, respectively. Smallwood et al. reasoned that if these two types of mind wandering are reflective of different processes, then they should be dissociable, both behaviorally and neurologically. Consistent with the idea that these two types of mind wandering have separable properties, Smallwood and colleagues demonstrated that, compared to mind wandering with awareness, mind wandering without awareness is more strongly associated with response-inhibition failures (Smallwood McSpadden, et al., 2007; Smallwood, McSpadden, Luus, & Schooler, 2008) as well as reading-comprehension deficits (Smallwood, McSpadden, & Schooler, 2008). Moreover, in subsequent work, Christoff et al. (2009) showed that tuned-out (aware) and zoned-out (unaware) mind wandering also show different patterns of brain activity. Taken together, these results suggest that tuned-out and zoned-out mind wandering each have different implications for task performance and neurocognitive activity, and that they reflect the operation of unique cognitive processes. Importantly, this observation has in turn been taken to suggest the theoretical importance of distinguishing between aware and unaware mind wandering in investigations on the topic.

The level of intentionality of mind wandering: Intentional versus unintentional

In his pioneering work on the topic, Giambra (1995) made a distinction between mind wandering that is uncontrolled and that which is controlled: “TUITs [i.e., task-unrelated imagery and thoughts] may occupy awareness because they capture our attention – an uncontrolled shift – or because we have deliberately shifted our attention to them – a controlled shift” (p. 2). Although theoretical consideration of the intentionality of mind wandering has largely been absent over the past few decades, in a recent series of studies, some researchers have revisited the distinction between intentional and unintentional mind wandering (Forster & Lavie, 2009; Seli, Cheyne, et al., 2015; Seli, Risko, Purdon, & Smilek, 2016; Seli, Risko, & Smilek, 2016b; Seli, Smallwood, Cheyne, & Smilek, 2015; Seli, Wammes, et al., 2015). Critically, in some of this research it has been shown that these two types of mind wandering appear to reflect unique cognitive experiences. Indeed, it has been shown that rates of intentional and unintentional mind wandering can be differentially affected by certain experimental manipulations (Phillips, Mills, D’Mello, & Risko, 2016; Seli, Risko, & Smilek, 2016b). For example, Seli, Risko, and Smilek (2016) showed that participants reported more intentional mind wandering in an easy than in a difficult task, and, conversely, more unintentional mind wandering in a difficult than an easy task.Footnote 1 Moreover, it has been shown that intentional and unintentional mind wandering are sometimes uniquely associated with certain variables of theoretical interest. For instance, whereas intentional mind wandering is positively associated with mindfulness (in particular, the non-reactivity component of the Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire; FFMQ), unintentional mind wandering is negatively associated with this same facet (Seli, Carriere, & Smilek, 2014). Finally, recent research has shown dissociations in terms of the neural associates of intentional and unintentional mind wandering (Golchert et al., 2017). Importantly, it has been suggested that these recent demonstrations of dissociations of intentional and unintentional mind wandering will play a key role in future research on mind wandering because such dissociations indicate that, to gain a clear understanding of the causes and consequences of the wandering mind, researchers need to distinguish between intentional and unintentional types of this experience (Seli et al., 2016b).

Juxtaposing intentionality and meta-awareness

Although the foregoing dissociations clearly indicate the theoretical importance of indexing the intentionality and meta-awareness of mind wandering, there nevertheless remains the concern that indices of meta-awareness and intentionality are actually redundant, and, hence, that making a distinction between these two dimensions would be fruitless. Indeed, it is reasonable to assume that a bout of mind wandering that is engaged with intention will necessarily include meta-awareness of its occurrence, and, conversely, that a bout of mind wandering that is engaged without intention will neces-sarily lack meta-awareness. While this view appears to be incontrovertible, Smallwood (2013) has recently proposed a nuanced theoretical view of mind wandering that takes into consideration the “ignition point” and the “continuation” of a mind-wandering episode, and this view suggests that the relation between meta-awareness and mind wandering could be more complex than meets the eye. From the perspective of the ignition/continuation distinction, the intuitive overlap between meta-awareness and intentionality need only be observed at the onset (or the “ignition point”) of the mind-wandering episode. Following the initiation of the episode (i.e., as the episode persists), however, intentionality and meta-awareness could, in theory, diverge. For example, an individual may intentionally initiate an episode of mind wandering (and hence, be meta-aware of its occurrence), yet she might become so deeply absorbed in her mind wandering that she eventually loses awareness of its occurrence. Similarly, an individual may unintentionally initiate an episode of mind wandering, yet gain awareness of its occurrence as the episode continues.

To date, although this latter account has gone without empirical testing, there is some initial (albeit indirect) evidence in the extant literature to support it. In particular, Smallwood et al. (2007) examined the meta-awareness associated with mind-wandering episodes that occurred while participants completed a simple go–no-go task. During the task, participants were intermittently presented thought probes that required them to indicate whether any mind wandering they experienced was associated with awareness (i.e., a tune-out) or without awareness (i.e., a zone out). Critically, Smallwood et al. found that when participants reported being zoned out, they produced significantly faster response times (RTs) to the go/no-go task than when they reported being tuned out. Given this finding, and given the assumption that intentional and unintentional mind wandering are redundant with tune-outs and zone outs (respectively), one should expect to find the same pattern of results when examining intentional and unintentional mind wandering during the same go/no-go task. More specifically, if intentional mind wandering is redundant with tune-outs, and if unintentional mind wandering is redundant with zone-outs, then one ought to find that periods of unintentional mind wandering are associated with faster RTs than are periods of intentional mind wandering (as in Smallwood et al., 2007). However, in recent work, Seli, Risko, and Smilek (2016) found no difference in go/no-go RTs across periods during which people were engaged in intentional and unintentional mind wandering, and this finding was taken as initial evidence to suggest that intentionality and awareness are not in fact redundant constructs. In interpreting this finding, however, it is worth noting that Seli et al.’s conclusion rested upon a null result, and as such, it provides weak evidence in support of the claim that intentionality and awareness are distinct dimensions of mind wandering. Thus, it remains unclear whether intentional and unintentional mind wandering are indeed redundant with tune-outs and zone-outs.

The Present Studies

Given the potential overlap between the intentionality and meta-awareness dimensions, as well as the purported theoretical importance of indexing these two dimensions, here, across two studies, we sought to explore whether these dimensions are redundant or distinct. To this end, in the first study we re-examined data from two previously published studies: one in which meta-awareness was examined via thought probes (Study 1a; Seli, Cheyne, & Smilek, 2013), and the other in which intentionality was examined via thought probes (Study 1b; Seli, Cheyne, et al., 2015). Critically, both studies employed the exact same sustained-attention task (the Metronome Response Task (MRT); Seli, Carriere, Levene, & Smilek, 2013; Seli, Cheyne, et al., 2013), and in both studies, participants completed the same number of MRT trials (900) with the same number of thought probes (18). This overlap allowed us to examine reported rates of tuned-out and zoned-out mind wandering in Study 1a, and to then compare these to rates of intentional and unintentional mind wandering in Study 1b. Here, the rationale was that if tune-outs and zone-outs are redundant with intentional and unintentional mind wandering, respectively, then the relative pattern of tune-outs to zone-outs and intentional to unintentional mind wandering should be the same; as such, we should not observe a study (Study 1a, Study 1b) by report type (intentional mind wandering/tune-outs, unintentional mind wandering/zone-outs) interaction.

In our second study, we were interested in indexing both intentionality and meta-awareness within a single session, and determining whether tuned-out mind wandering was sometimes associated with a lack of intention, and whether zoned-out mind wandering was sometimes associated with intention. Given the argument that tune-outs are always associated with intention, and that zone-outs are always associated with a lack of intention, such a finding would suggest that the dimensions of intentionality and meta-awareness are not in fact redundant.

Study 1 (reanalysis of published data)

As noted above, in Study 1 we re-examined previously published data from two studies that indexed mind wandering via thought probes while participants completed a sustained-attention task (the MRT). Importantly, these two studies were identical, except that one study indexed meta-awareness of mind wandering (Study 1a; Seli, Cheyne, et al., 2013) whereas the other indexed the intentionality of mind wandering (Study 1b; Seli, Cheyne, et al., 2015).Footnote 2 Of primary interest here is determining whether there is a qualitative difference between rates of tune-outs and zone-outs, and intentional and unintentional mind wandering, which would provide initial evidence to suggest that meta-awareness and intentionality are dissociable dimensions of mind wandering.

Method

Participants

Participants in Study 1a (Seli, Cheyne, et al., 2013) were 82 undergraduate students enrolled in psychology courses at the University of Waterloo. Consistent with Seli, Cheyne, et al. (2013), here we excluded data from two participants because they failed to respond to at least 10% of the MRT trials, which indicates a failure to comply with instructions. Hence, all analyses for Study 1a included data from 80 participants.

Participants in Study 1b (Seli, Cheyne, et al., 2015) were 166 undergraduate students enrolled in psychology courses at the University of Waterloo. Because Seli, Cheyne, et al. (2015) were interested in examining the proportion of mind wandering that was intentional versus unintentional, they excluded data from two participants who did not report any mind wandering and could therefore not contribute to the analysis of interest. However, in the present analysis, given that we were interested in examining overall rates of intentional and unintentional mind wandering, it was not problematic to include data from these two participants. It should be noted, however, that none of the subsequently presented results differ when these data are excluded from our analyses.

Apparatus

In both Study 1a and Study 1b, stimulus presentation was controlled by an Acer Aspire AX1930-ES10P desktop computer. The MRT program was constructed using E-Prime 1.2 software (Psychology Software Tools Inc., Pittsburgh, PA, USA). Auditory stimuli were presented to participants via Sony MDR-XD200 Stereo Headphones.

The metronome response task (MRT)

The MRT (Seli, Cheyne, et al., 2013) is a sustained-attention task that requires participants to monitor the passage of time so that they can produce a key-press response in synchrony with a periodic tone. In both Study 1a and Study 1b, each MRT trial began with 650 ms of silence followed by the presentation of a tone (75 ms) and a further 575 ms of silence. Hence, the total trial duration was 1,300 ms. Participants were instructed to respond (“press the spacebar”) synchronously with each tone so that their responses were made at the exact time at which each tone was presented. Participants first completed 18 practice trials intended to familiarize them with the task, after which they completed 900 experimental trials.

Thought probes

In both Study 1a and Study 1b, one thought probe was randomly presented in each block of 50 trials (for a total of 18 probes). In Study 1a, upon presentation of each probe, the MRT stopped and participants were asked to indicate (via key press) whether they were, just prior to the onset of the probe, (1) on task, (2) tuned-out (i.e., mind wandering with awareness), or (3) zoned-out (i.e., mind wandering without awareness; see Supplemental Material for exact probe instructions). After providing a response to each thought probe, participants were instructed to press the spacebar to resume the MRT. In Study 1b, upon presentation of each probe, the MRT stopped and participants were asked to indicate (via key press) whether they were, just prior to the onset of the probe, (1) on task, (2) intentionally thinking about task-unrelated thoughts, or (3) unintentionally thinking about task-unrelated thoughts (see Supplemental Material for exact probe instructions). As was the case in Study 1a, after providing a response to each thought probe, participants were instructed to press the spacebar to resume the MRT.

Rates of mind wandering

In Study 1a, we calculated the proportion of tune-outs and zone-outs by dividing the number of each type of report by the total number of thought probes (18). In Study 1b, the same calculation was used, except that here we divided the number of reports of intentional and unintentional mind wandering by the total number of thought probes (18).

Results

First, we were interested in examining overall rates of mind wandering in Studies 1a and 1b to ensure that these rates did not differ. Such an analysis is important because, even in the case that meta-awareness and intentionality are unique dimensions of mind wandering, one should expect to observe the same rate of overall mind wandering across Study 1a and Study 1b because they were identical in every way except in terms of the thought probes administered. We computed the overall proportion of mind wandering for each study by summing the proportion of tune-outs and zone-outs (Study 1a) and by summing the proportion of intentional and unintentional mind wandering (Study 1b). An independent-samples t test indicated that rates of overall mind wandering in Study 1a (M = .64, SD = .24) were not significantly different from rates of overall mind wandering in Study 1b (M = .60, SD = .25), t(244) = 1.116, SE = 0.03, p = .266, d = .16. To determine whether there was evidence in favor of this ostensible null, we used Masson’s (2011) Bayesian Model Selection Approach, which yielded the following posterior probability values: p BIC (H0 |D) = 0.893 and a p BIC (H1 |D) = 0.107. Critically, these posterior probability values indicate that the data provide positive support for the null hypothesis over the alternative hypothesis (Masson, 2011).

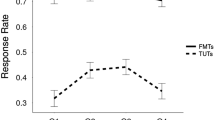

Next, we wanted to examine the respective patterns of tune-outs and zone-outs (Study 1a), and intentional and unintentional mind wandering (Study 1b) (see Fig. 1). Recall that the rationale here is that, if intentional mind wandering is redundant with tuned-out mind wandering, and if unintentional mind wandering is redundant with zoned-out mind wandering, then one should expect that the relative pattern of tune-outs to zone-outs and of intentional to unintentional mind wandering is the same. However, in examining the difference score between zone-outs and tune-outs (i.e., zone-outs minus tune-outs) and the difference score between unintentional and intentional mind wandering (i.e., unintentional mind wandering minus intentional mind wandering), we found that these difference scores were significantly different from one another, t(244) = 6.222, SE = 0.04, p < .001, d = .87: Whereas participants in Study 1a reported more tune-outs than zone-outs, t(79) = 6.152, SE = 0.03, p < .001, d = .69, participants in Study 1b reported the reverse pattern, with more unintentional than intentional mind wandering, t(165) = 2.933, SE = 0.03, p = .004, d = .23.

Discussion

In comparing probe-caught rates of tune-outs and zone-outs to probe-caught rates of intentional and unintentional mind wandering, Study 1 provided some initial evidence to suggest that the dimensions of meta-awareness and intentionality are distinct. Specifically, we found the opposite pattern in terms of the relative rates of tune-outs and zone-outs, and intentional to unintentional mind wandering. In particular, we found that, in Study 1a, there were more tune-outs than zone-outs, whereas in Study 1b, there was more unintentional mind wandering than intentional mind wandering. Critically, across both studies, the tasks were identical, as were the overall rates of mind wandering. Thus, the difference in the relative rates of mind wandering across the two studies makes it difficult to maintain the claim that the dimensions of meta-awareness and intentionality are redundant.

Study 2

In Study 2, we sought to provide further support for the idea that the dimensions of meta-awareness and intentionality are distinct, and did so by examining meta-awareness and intentionality within a single study during which participants again completed the MRT. In this study, our primary goal was to determine whether people sometimes experience intentional mind wandering without meta-awareness, and additionally, unintentional mind wandering with meta-awareness. According to the view that mind wandering with awareness is redundant with intentional mind wandering, and that mind wandering without awareness is redundant with unintentional mind wandering, such outcomes should never be observed. Thus, if such outcomes were to emerge, this would provide additional support for the idea that meta-awareness and intentionality are unique dimensions of mind wandering that are worthy of separate consideration.

Study 2 was similar to Study 1 in that (1) participants completed the MRT, and (2) throughout the MRT, we indexed meta-awareness and intentionality. However, unlike Study 1, in Study 2, each participant provided reports of meta-awareness and intentionality (rather than one or the other; i.e., Study 2 used a within-subjects design). Moreover, rather than indexing meta-awareness via the probe-caught method (as in Study 1), in Study 2 we indexed meta-awareness by employing the self-catching procedure (Schooler, 2002). This procedure involves instructing participants to attempt to be aware of any mind wandering that they experience while completing the MRT, and upon becoming aware of a bout of mind wandering, to indicate such meta-awareness by producing a button press. Thus, any time participants self-catch their mind wandering, this process would reflect the engagement of meta-awareness. On the other hand, cases in which participants’ mind wandering is caught by the probe (rather than being self-caught and subsequently terminated) would reflect mind wandering without meta-awareness (Schooler, 2002).

To explore the possibility that mind wandering with awareness is sometimes accompanied by a lack of intention, we instructed participants to report on whether their episodes of self-caught mind wandering were engaged with or without intention. Moreover, to explore whether mind wandering without awareness is sometimes accompanied by intention, we instructed participants to report on whether their episodes of probe-caught mind wandering were engaged with or without intention.

Importantly, in Study 2, we decided to index meta-awareness via the self-catching procedure rather than the probe-catching procedure because of the concern that the latter procedure might produce biased responses when coupled with probe-caught reports of intentionality. Indeed, it might be the case that after providing a probe-caught report of mind wandering with awareness, participants may be biased to then believe that their mind wandering must have occurred intentionally, even if it had occurred unintentionally. Conversely, it might be the case that after providing a probe report of mind wandering without awareness, participants may be biased such that they then believe that the mind wandering occurred unintentionally, even if it did not. Given this concern, and given that the self-caught procedure has been previously used to index meta-awareness (e.g., Schooler, 2002), we reasoned that it would be most sensible to employ the self-caught procedure in Study 2. In addition to alleviating the foregoing concern, the use of the self-catching procedure also allowed us the opportunity to provide a conceptual replication of our findings from Study 1 while using a different index of meta-awareness.

Method

Participants

Participants were 80 undergraduate students enrolled in psychology courses at the University of Waterloo. As in Study 1, we excluded data from any participants who failed to respond to at least 10% of the MRT trials, which resulted in the exclusion of data from two participants.

Apparatus

In Study 2, the MRT was constructed using Python 2.7 (Python Software Foundation) and run on an Apple Mini with OS X 10.6.6. Instructions and thought probes were presented on a 24-in. Phillips 244E LCD monitor. Auditory stimuli were presented to participants via Sony MDR-XD200 Stereo Headphones.

The metronome response task (MRT)

All details of the MRT were identical to those presented in Study 1b, except that (1) participants were additionally instructed to self-catch their mind wandering by pressing the “m” key at any point during the task if they noticed that their minds had wandered, and (2) after self-catching, participants were required to report (via key press) whether their self-caught episode of mind wandering was engaged with or without intention.

Rates of mind wandering

For each participant, we calculated the proportion of intentionally and unintentionally engaged probe-caught mind wandering by dividing the number of each type of report by the total number of thought probes (18). In addition, we computed the number of intentionally and unintentionally engaged self-caught mind-wandering episodes by summing the number of each report type for each participant.

Results

In examining the psychometric properties of our primary measures, we found that skewness and kurtosis values for the following variables exceeded acceptable ranges (skewness >2, kurtosis> 4; Kline, 1998): (1) The proportion probe-caught mind wandering that was intentional, (2) The count of self-caught mind wandering that was intentional, and (3) The count of self-caught mind wandering that was unintentional. In visualizing the data, it appeared that these non-normal distributions may have been attributable to a few outliers. Thus, our conservative strategy was to define outliers, via boxplots, as any observations falling three or more times the interquartile range (IQR) away from the upper or lower hinges of the plot for each of these three measures. In doing so, we identified five outliers. After removing all data from the five participants who produced outlier observations, we found that skewness and kurtosis values were within an acceptable range (skewness <2, kurtosis< 4; Kline, 1998; see Table 1).

As can be seen in Table 1, participants reported intentional mind wandering to roughly 12% of the thought probes, and a one-sample t test comparing this rate of mind wandering to 0 indicated that it was significantly greater than 0, t(72) = 8.846, SD = 0.12, p < .001, d = 1.04. From the perspective of Schooler (2002), because probe-caught mind wandering is believed to reflect mind wandering without meta-awareness, this result suggests that participants sometimes intentionally initiate mind wandering that, at some later point in time, persists without meta-awareness. As noted above, if meta-awareness and intentionality were redundant dimensions, then one would not expect people to ever report intentionally engaged mind wandering that occurs without meta-awareness of its occurrence.

Interestingly, in examining previously reported data, one could draw the above-mentioned conclusion by way of inference. Indeed, a few studies have now reported similar rates of probe-caught mind wandering (or mind wandering without meta-awareness) that was engaged with intention (Seli, Cheyne, et al., 2015; Seli, Risko, & Smilek, 2016a, 2016b; Seli, 2016). Nonetheless, until now, the hypothesis that people sometimes intentionally initiate such mind wandering has not been formally tested, and this finding has not been raised in discussions of the similarities/differences between meta-awareness and intentionality. In addition, to date, no research has examined the possibility that people might sometimes unintentionally engage in mind wandering that, at some point, is associated with meta-awareness. Importantly, such a finding would complement the former finding and provide further evidence to suggest that meta-awareness and intentionality are distinct dimensions. Thus, we next explored this possibility by examining the extent to which participants reported unintentional mind wandering that was self-caught, finding that, on average, participants reported such mind wandering 3.64 times during the MRT. Critically, a one-sample t test indicated that this value was significantly different from 0, t(72) = 6.440, SD = 4.83, p < .001, d = .75. If mind wandering with meta-awareness is redundant with intentional mind wandering, then it is not clear why people would ever report unintentionally engaged mind wandering with meta-awareness. In fact, if we examine the overall proportion of self-caught mind wandering that was labelled as occurring unintentionally, we find a value of roughly .74; put differently, 74% of mind wandering with meta-awareness was engaged without intention.Footnote 3 Clearly, this result, and the former result, indicate that intentionality and meta-awareness are unique dimensions.

Discussion

In Study 2, we extended the findings from Study 1 by further exploring the possibility that meta-awareness and intentionality are distinct dimensions of mind wandering. To this end, we assessed both dimensions within a single experimental session so that we could determine whether people report the experience of mind wandering that is associated with (1) intention, but a lack of meta-awareness of its occurrence, and (2) a lack of intention, but meta-awareness of its occurrence. On the view that meta-awareness and intentionality are redundant dimensions, and in particular, that mind wandering with meta-awareness is redundant with intentional mind wandering, and that mind wandering without meta-awareness is redundant with unintentional mind wandering, such findings should not be observed. However, results of Study 2 indicated that people reported statistically significant levels of both types of mind wandering, which thereby provides further evidence that meta-awareness and intentionality are unique dimensions of the mind-wandering experience.

General discussion

In a recent series of studies (Phillips et al., 2016; Seli et al., 2014; Seli, Risko, Purdon, et al., 2016; Seli, Risko, & Smilek, 2016b; Seli, Smallwood, et al., 2015), researchers have demonstrated dissociations between intentional and unintentional mind wandering, and on the basis of these findings, it has been suggested that future research on the topic of mind wandering ought to assess and separately evaluate intentional and unintentional types of mind wandering (Seli, Risko, & Smilek, 2016b; Seli et al., 2016). At the same time, however, there has been some concern that the dimension of intentionality might be redundant with one of the more popular dimensions of mind wandering: meta-awareness. If this were the case, then there would be little reason to take seriously the recent call for researchers to consider the intentionality of mind wandering in future investigations. In the present work, across two studies, we provided evidence to suggest that the dimensions of meta-awareness and intentionality are in fact distinct. Indeed, if these two dimensions were redundant, then one would expect that (1) the relative pattern of tune-outs to zone-outs and intentional to unintentional mind wandering should be the same, and (2) people would not report mind wandering that was intentionally engaged and lacking meta-awareness, and unintentionally engaged but associated with meta-awareness. However, as demonstrated here, these expectations were not borne out. Instead, in Study 1, we found the opposite pattern in terms of the relative rates of zone-out to tune-outs and unintentional to intentional mind wandering: In Study 1a, there were more tune-outs than zone-outs, whereas in Study 1b, there was more unintentional mind wandering than intentional mind wandering. In addition, in Study 2, we found that people reported a significant (non-zero) number of mind-wandering episodes that were intentionally engaged but lacking meta-awareness, as well as a significant (non-zero) number of episodes that were unintentionally engaged but (at least at some point) associated with meta-awareness. Thus, the present findings indicate that not only are meta-awareness and intentionality unique dimensions, but moreover, that there is indeed good reason for researchers to index the intentionality of mind wandering in future studies, as recently suggested (Seli, Risko, & Smilek, 2016b; Seli et al., 2016).

In considering the results of both Study 1 and 2, the dynamic nature of mind-wandering episodes seems clear. Indeed, given (1) the seemingly undeniable assumption that intentionality and meta-awareness must overlap at the ignition point of an episode,Footnote 4 and (2) the finding that, at other points during the episode, these dimensions do not overlap, it is necessarily the case that intentionality and meta-awareness of mind wandering fluctuate (sometimes in opposing directions) as the episode continues. For example, if meta-awareness and intentionality always took the same trajectory (with tune-outs always being accompanied by intention and zone-outs always being accompanied by a lack of intention), then in Study 1, we should not have observed differences in their respective patterns, with more tune-outs than zone-out, but more unintentional than intentional mind wandering. In addition, in examining Table 1, we see that participants reported a significant number of unintentionally engaged episodes of mind wandering that were later self-caught (and in fact, the number of such experiences was significantly greater than the number of intentionally engaged episodes that were later self-caught, t(72) = 4.945, SD = 4.19, p < .001, d = .67). In considering the inception of such an episode, it seems safe to conclude that this episode was not only engaged without intention (assuming that the participant’s report is veridical), but moreover, that the participant was also, at the time of initiation of the mind-wandering episode, unaware of its occurrence. However, in order for a participant to subsequently self-catch an unintentionally engaged episode of mind wandering of which he was previously unaware, he must have later gained awareness of the episode. Thus, these findings indicate that although the intentionality associated with a given mind-wandering episode might be fixed at its inception, meta-awareness may dynamically unfold as the episode continues. Moreover, given that participants reported significantly more experiences of unintentionally engaged mind wandering with meta-awareness than they did intentionally engaged mind wandering without meta-awareness, it appears that most bouts of mind wandering begin unintentionally, but eventually the individual becomes aware that she is mind wandering.

That said, these conclusions all rest upon the assumption that when participants report on the intentionality of mind wandering, they inform these reports by the actual intentionality associated with the onset of the episode. Although the thought-probe instructions imply that this is how participants ought to report on the intentionality of their mind wandering, whether this is in fact how they inform their reports is an open question. Indeed, evidence suggests that at least under some circumstances people can erroneously ascribe intentionality to behaviors that in fact were not self initiated (Wegner & Wheatley, 1999). The factors that inform self-reports of meta-awareness of mind-wandering may similarly include considerations that go beyond the process of meta-awareness itself. For example, in deciding when to self-catch mind wandering, people may rely on some criterion entailing the degree to which their minds must be off task before they opt to report it. In line with this view, recent evidence supports such a process by demonstrating that incentivizing people to self-catch mind wandering can increase the frequency of self-catches and the correspondence between self-catching and behavioural measures (Zedelius et al., 2015). Although more research is required to evaluate the precise mapping among people’s self-reports of intentionality and meta-awareness and the actual processes underpinning these mental states, it is heartening that assessing the authenticity of these reports is a topic that can lend itself to empirical investigation, potentially using similar tools to those that have been used in evaluating self-reports of mind-wandering itself (cf. Seli, Jonker, et al., 2015; Schooler 2015)

Another important topic to consider in the context of the present studies is what, precisely, does it mean to mind-wander with intention?Footnote 5 On the one hand, intentional mind wandering has often been viewed as the volitional initiation of a train of thought that is unrelated to one’s current external environment. On the other hand, however, it is possible that intentional mind wandering occurs not when an individual deliberately initiates a train of thought that is unrelated to the external environment, but instead when an individual is not attempting to attend to a focal task, and a spontaneously occurring thought pops into her mind. Of course, there is also the possibility that both of these types of intentional mind wandering are conflated in reports of intentional mind wandering. While the present studies provide little in the way of clarity on this topic, we believe that consideration of this topic will be important for future research on mind wandering. Indeed, it may be that both types of mind wandering occur, and that they are associated with different costs, in which case, separately examining these two types of intentional mind wandering will be important for both theory and practice.

Although current models of mind wandering (McVay & Kane, 2010; Smallwood, 2013; Thomson, Besner, & Smilek, 2015) do not explicitly deny the importance of meta-awareness and intentionality, they have nevertheless remained silent on the issue of how these distinctions might be explained. One interpretation of this silence is that these models may consider distinctions among intentional and unintentional mind wandering, and mind wandering with and without meta-awareness to be of secondary importance in the search for a theoretical understanding of mind wandering. For example, one might argue that all mind wandering is initiated in the same manner, and that the intentionality associated with the initiation merely reflects the individual’s retrospective rationalization of their wandering mind. However, this position becomes increasingly difficult to maintain in light of recent findings demonstrating dissociations of intentional and unintentional mind wandering and dissociations of mind wandering with and without meta-awareness. Considering this work, as well as the present demonstration that intentionality and meta-awareness reflect distinct dimensions, it would seem prudent to begin building a wider framework for understanding mind wandering: one that encompasses its distinct forms.

Finally, we point to an important implication that the present findings have for the broader psychological literature. Many studies in psychological science focus on delineating the basic properties and the limits of cognitive processes. In many of these investigations, the researcher’s interpretation of performance is often based on the assumption that participants are deliberately trying to fully focus on the task-set before them and that they are trying to perform optimally within the task context. In effect, at the beginning of a testing session, the researcher and the participant create a tacit contract regard-ing the responsibilities of the participant during the experimental task, with the participant often being expected to focus fully and perform optimally on the task. We suggest that although the experimenter often assumes that the participant fully adheres to this contract, the participant might take it less seriously, and at times allow himself to deviate from the instructions at various points throughout the task (for related research on strategic task approaches, see Schumacher et al. 2001). The unfortunate result of this disconnect is that we might draw conclusions that are flawed because they are based on incorrect assumptions about the participant’s level of task engagement. For instance, in the context of the literature on mind wandering, consider the standard interpretation of self-caught mind-wandering reports: Typically, it is assumed that a participant was diligently attempting to pay attention to the task, and that therefore, prior to reporting a self-caught moment of mind wandering, any mind wandering was engaged unwittingly. However, contrary to this assumption, the results of Study 2 show that at least some portion of mind-wandering episodes that were ultimately self-caught were actually engaged in with intention. Similarly, when a thought probe “catches” a participant mind wandering, it is typically assumed that the participant was attempting to attend to the task, and therefore, that probe-caught mind wandering captures mind wandering that occurred without meta-awareness: Indeed, if the participant were meta-aware of her mind wandering, then, the assumption goes, she would have reported (and terminated) her mind wandering prior to the presentation of the thought probe (Schooler, 2002), and as such, she would no longer be engaged in that bout of mind wandering upon presentation of the next thought probe. However, in Study 1a, we found that participants frequently reported tuned-out probe-caught mind wandering (i.e., mind wandering whose occurrence was apparent; see Fig. 1). Importantly, this suggests that participants are sometimes meta-aware of their mind wandering (and hence, able to self-catch), but that they nevertheless permit their mind wandering to continue until it is interrupted by a thought probe.

Moving beyond the mind-wandering literature to the broader literature on distraction, it seems reasonable to suggest that similar (and thus possibly incorrect) assumptions regarding the high diligence of participants are made when interpreting data to suggest that deleterious effects of irrelevant distractors are due to automatic (unintentional) processes (e.g., Theeuwes, 1994). Indeed, it might be that participants are “distracted” in these paradigms because they are simply not trying to ignore the distractors. Based on the foregoing, we suggest that psychological researchers should be cautious when proposing interpretations of data that require the assumption that participants were fully engaged and diligently attempting to optimize performance in the experimental setting.

Notes

It is worth noting that research has shown that when participants are given the option to endorse a given episode of mind wandering as being both intentional and unintentional, they very infrequently provide such an endorsement, and the number of such endorsements is not significantly different from zero (Seli, Wammes, et al., 2015). Importantly, this finding indicates that intentional and unintentional mind wandering are independent cognitive experiences.

One other difference between the two studies is that, in Study 1b (Seli, Cheyne, et al., 2015), participants were also asked to provide a response to a single question asking them about the extent to which they were motivated to perform well on the MRT. That said, this motivation question was presented at the very end of the study (i.e., after participants had completed the MRT and after they had provided thought-probe responses), and so it is a negligible detail in the present case.

This calculation necessarily includes only participants who self-caught their mind wandering at least once: N = 47.

In other words, that intentionally engaged mind wandering must be accompanied by awareness, and unintentionally engaged mind wandering must be accompanied by a lack of awareness.

Although it is important to consider problems surrounding the definition of “mind wandering” itself and to delineate how mind wandering differs from other types of thought, here we focus primarily on the dimension of intentionality.

References

Carriere, J. S. A., Seli, P., & Smilek, D. (2013). Wandering in both mind and body: Individual differences in mind wandering and inattention predict fidgeting. Canadian Journal of Experimental Psychology = Revue Canadienne De Psychologie Expérimentale, 67(1), 19–31. doi:10.1037/a0031438

Christoff, K., Gordon, A. M., Smallwood, J., Smith, R., & Schooler, J. W. (2009). Experience sampling during fMRI reveals default network and executive system contributions to mind wandering. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 106(21), 8719–24. doi:10.1073/pnas.0900234106

Forster, S., & Lavie, N. (2009). Harnessing the wandering mind: The role of perceptual load. Cognition, 111(3), 345–355. doi:10.1016/j.cognition.2009.02.006

Giambra, L. M. (1995). A laboratory method for investigating influences on switching attention to task-unrelated imagery and thought. Consciousness and Cognition. doi:10.1006/ccog.1995.1001

Golchert, J., Smallwood, J., Jefferies, E., Seli, P., Huntenburg, J. M., Liem, F., & Margulies, D. S. (2017). Individual variation in intentionality in the mind-wandering state is reflected in the integration of the default-mode, fronto-parietal, and limbic networks. NeuroImage, 146, 226–235.

Masson, M. E. (2011). A tutorial on a practical Bayesian alternative to null-hypothesis significance testing. Behavior Research Methods, 43, 679–690.

McVay, J. C., & Kane, M. J. (2010). Does mind wandering reflect executive function or executive failure? Comment on Smallwood and Schooler (2006) and Watkins (2008). Psychological Bulletin, 136(2), 188–197. doi:10.1037/a0018298

Phillips, N. E., Mills, C., D’Mello, S., & Risko, E. F. (2016). On the influence of re-reading on mind wandering. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 2006, 1–20. doi:10.1080/17470218.2015.1107109

Reichle, E. D., Reineberg, A. E., & Schooler, J. W. (2010). Eye movements during mindless reading. Psychological Science, 21(9), 1300–1310. doi:10.1177/0956797610378686

Schooler, J. W. (2002). Re-representing consciousness: Dissociations between experience and meta-consciousness. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 6(8), 339–344. doi:10.1016/S1364-6613(02)01949-6

Schooler, J. W. (2015). Bridging the objective/subjective divide - Towards a meta-perspective of science and experience. In T. Metzinger & J. M. Windt (Eds). Open MIND: 34(T). Frankfurt am Main: MIND Group. doi: 10.15502/9783958570405

Schooler, J. W., Reichle, E. D., & Halpern, D. V. (2004). Zoning out while reading: Evidence for dissociations between experience and metaconsciousness. In D. Levin (Ed.), Thinking and seeing: Visual metacognition in adults and children (pp. 203–226). Cambridge: MIT Press.

Schooler, J. W., Smallwood, J., Christoff, K., Handy, T. C., Reichle, E. D., & Sayette, M. A. (2011). Meta-awareness, perceptual decoupling and the wandering mind. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 15(7), 319–326. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2011.05.006

Schumacher, E. H., Seymour, T. L., Glass, J. M., Fencsik, D. E., Lauber, E. J., Kieras, D. E., & Meyer, D. E. (2001). Virtually perfect time sharing in dual-task performance: Uncorking the central cognitive bottleneck. Psychological Science, 12, 101–108.

Seli, P. (2016). The attention-lapse and motor decoupling accounts of SART performance are not mutually exclusive. Consciousness and Cognition, 41, 189–198. doi:10.1016/j.concog.2016.02.017

Seli, P., Carriere, J. S. A., Levene, M., & Smilek, D. (2013). How few and far between? Examining the effects of probe rate on self-reported mind wandering. Frontiers in Psychology, 4(JUL). doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00430

Seli, P., Carriere, J. S. A., & Smilek, D. (2014). Not all mind wandering is created equal: dissociating deliberate from spontaneous mind wandering. Psychological Research, 79(5), 750–758. doi:10.1007/s00426-014-0617-x

Seli, P., Cheyne, J. A., Xu, M., Purdon, C., & Smilek, D. (2015). Motivation, intentionality, and mind wandering: Implications for assessments of task-unrelated thought. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 41(2), 1–9. doi:10.1037/xlm0000116

Seli, P., Cheyne, J. A., & Smilek, D. (2013). Wandering minds and wavering rhythms: Linking mind wandering and behavioral variability. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 39(1), 1–5. doi:10.1037/a0030954

Seli, P., Jonker, T. R., Cheyne, J. A., Cortes, K., Smilek, D., Seli, P., & Smilek, D. (2015). Can research participants comment authoritatively on the validity of their self-reports of mind wandering and task engagement ? Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 41(3), 703–709. doi:10.1037/xhp0000029

Seli, P., Risko, E. F., Purdon, C., & Smilek, D. (2016). Intrusive thoughts: linking spontaneous mind wandering and OCD symptomatology. Psychological Research. doi:10.1007/s00426-016-0756-3

Seli, P., Risko, E. F., Smilek, D., & Schacter, D. L. (2016). Mind-wandering with and without intention. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 20, 605–617.

Seli, P., Risko, E. F., & Smilek, D. (2016a). Assessing the associations among trait and state levels of deliberate and spontaneous mind wandering. Consciousness and Cognition, 41, 50–56. doi:10.1016/j.concog.2016.02.002

Seli, P., Risko, E. F., & Smilek, D. (2016b). On the necessity of distinguishing between unintentional and intentional mind wandering. Psychological Science, 0956797616634068–. doi:10.1177/0956797616634068

Seli, P., Smallwood, J., Cheyne, J. A., & Smilek, D. (2015). On the relation of mind wandering and ADHD symptomatology. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 22(3), 629–36. doi:10.3758/s13423-014-0793-0

Seli, P., Wammes, J. D., Risko, E. F., & Smilek, D. (2015). On the relation between motivation and retention in educational contexts: The role of intentional and unintentional mind wandering. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. doi:10.3758/s13423-015-0979-0

Smallwood, J. (2013). Distinguishing how from why the mind wanders: A process-occurrence framework for self-generated mental activity. Psychological Bulletin, 139(3), 519–35. doi:10.1037/a0030010

Smallwood, J., McSpadden, M., Luus, B., & Schooler, J. (2008). Segmenting the stream of consciousness: The psychological correlates of temporal structures in the time series data of a continuous performance task. Brain and Cognition, 66(1), 50–56. doi:10.1016/j.bandc.2007.05.004

Smallwood, J., McSpadden, M., & Schooler, J. W. (2007). The lights are on but no one’s home- the decoupling of executive resources when the mind-wanders. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 14. doi:10.1016/j.bandc.2007.05.004

Smallwood, J., McSpadden, M., & Schooler, J. W. (2008). When attention matters: The curious incident of the wandering mind. Memory & Cognition, 36(6), 1144–50. doi:10.3758/MC.36.6.1144

Theeuwes, J. (1994). Stimulus-driven capture and attentional set: Selective search for color and visual abrupt onsets. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 20(4), 799.

Thomson, D. R., Besner, D., & Smilek, D. (2015). A resource-control account of sustained attention: Evidence from mind-wandering and vigilance paradigms. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 10(1), 82–96. doi:10.1177/1745691614556681

Wegner, D., & Wheatley, T. (1999). Apparent mental causation: Sources of the experience of will. American Psychologist, 54, 480–492.

Zedelius, C. M., Broadway, J. M., & Schooler, J. W. (2015). Motivating meta-awareness of mind wandering: A way to catch the mind in flight? Consciousness and Cognition, 36, 44–53. doi:10.1016/j.concog.2015.05.016

Author note

This research was supported by a Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) discovery grant to Daniel Smilek, and NSERC Post-Doctoral Fellowship to Paul Seli. Daniel Schacter was supported by National Institute on Aging grant AG08441.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Seli, P., Ralph, B.C.W., Risko, E.F. et al. Intentionality and meta-awareness of mind wandering: Are they one and the same, or distinct dimensions?. Psychon Bull Rev 24, 1808–1818 (2017). https://doi.org/10.3758/s13423-017-1249-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.3758/s13423-017-1249-0