Abstract

We examined the extent to which speakers take into consideration the addressee’s perspective in language production. Previous research on this process had revealed clear deficits (Horton & Keysar, Cognition 59:91–117, 1996; Wardlow Lane & Ferreira, Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition 34:1466–1481, 2008). Here, we evaluated a new hypothesis—that the relevance of the addressee’s perspective depends on the speaker’s goals. In two experiments, Korean speakers described a target object in situations in which the perspective status of a competitor object (e.g., a large plate when describing a smaller plate) was manipulated. In Experiment 1, we examined whether speakers would use scalar-modified expressions even when the competitor was hidden from the addressee. The results demonstrated that information from both the speaker’s and the addressee’s perspectives influenced production. In Experiment 2, we examined whether utterance goals modulate this process. The results indicated that when a speaker makes a request, the addressee’s perspective has a stronger influence than it does when the speaker informs the addressee. These results suggest that privileged knowledge does shape language use, but crucially, that the degree to which the addressee’s perspective is considered is shaped by the relevance of the addressee’s perspective to the utterance goals.

Similar content being viewed by others

A central question in language production is the degree to which speakers take into account the addressee’s perspective. For example, imagine a dialogue situation in which a speaker refers to a mutually known object (e.g., a plate), in a context with a size-contrasting object that is visible to the speaker but hidden from the addressee (e.g., a smaller plate). In this situation, the speaker can refer to her intended referent as either the big plate or the plate, depending on whether she designs her expression from her own egocentric perspective or from the addressee’s perspective. The egocentric expression, the big plate, would uniquely identify the referent from the speaker’s perspective but would be overmodified from the addressee’s perspective. Instead, if the speaker considered what information was mutually known—that is, the common ground—he or she would likely refer to the object using the expression the plate. The present research examines whether speakers, in situations such as this one, design expressions with respect to common ground. We examined this question in a new participant population—Koreans—and investigated the potential role for previously unconsidered modulating factors—in particular, for utterance goals.

According to Grice’s maxims of quantity, speakers are assumed to produce expressions that are as informative as required, and therefore that are neither under- nor overinformative. In the scenario above, a cooperative speaker would be expected to use a bare noun, as the use of a scalar modifier would be noncooperative, a violation of the maxim of quantity. However, in natural conversation, speakers are not strictly Gricean. Furthermore, while overinformative expressions can result in confusion (Wardlow Lane & Ferreira, 2008), in many cases they may play an advantageous role (Deutsch, 1976).

Perspective in production: two views

When do speakers take into consideration the addressee’s perspective when designing referential expressions? Two prominent views have emerged. According to the constraint-based-processing view, multiple sources of information, including contextual information and the perspective of the addressee, combine to constrain language comprehension and production processes (Hanna, Tanenhaus & Trueswell, 2003; Horton, 2007; Tanenhaus & Trueswell, 1995). This view predicts early and strong contributions of common ground to referential production in cases where this information is well-established and relevant (Brown-Schmidt & Hanna, 2011).

In contrast, the egocentric-heuristics view proposes that expressions are initially designed from the speaker’s egocentric perspective (Horton & Keysar, 1996). The speaker monitors the addressee for understanding, and in cases of confusion, adjusts the expression to meet the addressee’s needs. This view is motivated by an assumption that incorporating common ground into routine language processes would be too resource-intensive (Keysar, Barr, Balin & Paek, 1998; Keysar, Lin & Barr, 2003).

Perspective in production: previous research

Despite claims that common ground is central to language (Clark, 1996), and despite a clear division between processing theories that hypothesize a central role for common ground in language production (Heller, Gorman & Tanenhaus, 2012) and those that do not (Horton & Keysar, 1996), relatively little work has investigated this question experimentally. Furthermore, most of this work has been conducted in a single participant population—speakers of American English—which is a limitation given recent evidence that Americans show specific deficits in perspective-taking abilities (Wu & Keysar, 2007).

Some research has suggested that the addressee’s perspective is only relevant during a delayed, second stage of production. Horton and Keysar (1996) asked speakers to describe a moving target object in the context of a second, competitor object that was either in common ground or in the speaker’s privileged ground (e.g., a small circle in the context of a larger circle). The speaker’s goal was to describe the target so that the addressee could determine whether he or she saw the same object move. In one condition, speakers were placed under time pressure. If utterances are initially designed with respect to common ground, Horton and Keysar argued that speakers should design their utterances with respect to the addressee’s perspective. In the absence of time pressure, speakers were significantly more likely to include a contextually relevant adjective (e.g., small) when the context object was common-ground. This effect was eliminated in the speeded condition, consistent with the claim that use of perspective is time-consuming.

Similarly, Wardlow Lane, Groisman, and Ferreira (2006; see also Wardlow Lane & Ferreira, 2008; Wardlow Lane & Liersch, 2012) evaluated whether speakers could control privileged information when it would be communicatively disadvantageous. Speakers referred to a mutually known object in a context that contained a size-contrasting object in the speaker’s privileged ground. The speaker’s goal was to describe the target so that the addressee could identify it. In one condition, speakers were instructed to conceal the identity of the privileged object. If use of perspective is under speakers’ control, speakers should be less likely to use a modifier when instructed to conceal the identity of the privileged object, because scalar modification implies contrast (Sedivy, 1999). Surprisingly, scalar modification rates were higher when speakers were instructed to conceal, suggesting that privileged information is automatically incorporated into referential processes, and thus is outside the speaker’s control.

Other results have shown moderate effects of perspective on production. Nadig and Sedivy (2002) found that even 5- to 6-year-old children, who are often considered egocentric (Epley, Morewedge & Keysar, 2004), showed successful use of common ground in both production and comprehension in situations in which the communicative goal was to request that the communicative partner pick up an object. Similarly, Heller et al. (2012) found that while speakers sometimes referred to privileged information when making requests, they successfully distinguished privileged information from common ground in the same utterances. Other research showed that audience design is impaired in children with high-functioning autism, and is related to their language ability (Nadig, Vivanti & Ozonoff, 2009).

Culture and perspective

Previous research on the role of perspective in production has largely been limited to a single population—Americans—and has observed serious deficits. However, recent findings in language comprehension suggest that deficits in perspective-taking may not extend to participants from other cultures. Wu and Keysar (2007) found that Chinese participants, unlike their American counterparts, were highly sensitive to common ground during language comprehension. These findings were interpreted in line with arguments that people from individualist cultures (e.g., the United States) are more egocentric than those from interdependent cultures (e.g., China). Thus, a key open question is whether limitations on the use of perspective during language production would extend to individuals from a different culture. If so, this would address whether previous findings of limitations in audience design (e.g., Horton & Keysar, 1996; Wardlow Lane, Groisman & Ferreira, 2006) generalize crossculturally.

Utterance goals

The speaker’s communicative goals in producing an utterance are an essential (if not the essential) component of language production. However, little to no research has examined how goals affect the use of perspective in production. Utterance goals include the expression of a statement, question, command, or desire (Searle, 1969). Crucially, perspective plays a different role in each goal. For example, during language comprehension, privileged ground is particularly relevant to interpretation of questions (Brown-Schmidt, Gunlogson & Tanenhaus, 2008), whereas common ground is relevant for imperatives (Hanna et al., 2003). In the previous research on audience design, the speaker’s communicative goal was not considered or manipulated, though in studies that found limitations on audience design in adults (Horton & Keysar, 1996; Wardlow Lane et al., 2006), the speaker’s goal was to describe for the purpose of the addressee identifying a referent. In the one study that has used request goals (Nadig & Sedivy, 2002), young children did show sensitivity to common ground, but like the studies with adults, also showed some egocentric interference.

Here, we directly examined whether goals influence perspective-taking in language production. Specifically, we asked whether the goals of informing versus requesting make different demands on perspective-taking. To inform is to state a situation. Presumably, then, informing can effectively proceed from the speaker’s perspective, thus allowing the speaker to bring new, previously privileged information into common ground. By contrast, to request is to command. If the speaker wants the addressee to comply, it is critical that the addressee be able to understand the request from his or her own perspective. Thus, here we test the hypothesis that speakers should consider the addressee’s perspective more when requesting than when informing.

Experiment 1

The goal of Experiment 1 was to test whether audience design failures would extend to a new participant population (Koreans), as well as to set the stage for Experiment 2. Specifically, we examined whether speakers would use scalar-modified noun phrases to identify objects in contexts in which the modifiers were not informative to the addressee. If previous findings in an American sample (Horton & Keysar, 1996) extended to a Korean sample, we would expect our speakers to produce scalars more often when modification would be informative to the addressee, and that there would be partial interference from the speaker’s privileged perspective.

Method

Participants

A group of 18 undergraduates at Seoul National University participated in the experiment as speakers in return for course credit, along with a confederate research assistant. All were native Korean speakers. An informal postexperimental interview determined that all but one participant believed that they were interacting with another participant (rather than a confederate).

Materials

A total of 78 objects were grouped into six sets of 13 objects each, with three critical pairs of objects per set (i.e., three targets and three competitors), plus seven distractor objects. The participants completed 18 critical and 18 additional, filler trials.

In three critical conditions, we manipulated the number of competitor objects and whether they were mutually visible to the speaker and addressee (see Fig. 1). In the one-object condition (baseline), there was a single target object (e.g., a cup). In the two-object condition, there were two mutually visible critical objects, a target and a competitor (e.g., a small candle and a big candle). The competitor object was always of the same type but was larger than the target (in this experiment, the target was always the smaller item). In the two-object-privileged condition, the target was shared and the competitor was privileged (e.g., a small plate and a big plate). While the speaker saw both the target and the competitor, a curtain occluded the competitor from the addressee’s view.

All items were counterbalanced across the three conditions, and their positions on the grid were rotated through the three critical conditions across three lists.

Procedure

The participant and the confederate sat on either side of a 5 × 5 grid with objects in some slots. Two 10-in. mini notebook computers, one assigned to a participant and one to the confederate, displayed instruction pictures during the task. Four slots were blocked with a curtain on one side of the grid. Critically, in the two-object-privileged condition, the curtain blocked the competitor object from the addressee’s view.

The task was a referential communication task. At the beginning of each set, the participant was asked to place the objects to duplicate a scene presented on his or her laptop. While the participant was putting the objects in the grid, the confederate turned his back so that he could not see the objects. While the confederate knew which objects were in the grid, the participant was told that the confederate did not know this information. After the participant had placed the objects, the experimenter blocked four slots with black curtains.

The confederate then faced the participant, and the experimenter asked the confederate to name each object that could be seen in the grid. The confederate then named each object using a bare noun (bare nouns were used in all conditions to avoid influencing the participant’s productions). The naming procedure was employed to make it clear to the participants that they and their partner (the confederate) had different perspectives, and to establish which objects were common ground.

After the confederate had named and identified each object, the confederate and participant took turns asking each other to pick up an object. When it was the confederate’s turn to speak, the confederate always referred to filler objects and did not use adjectives. The participants were allowed to say anything they needed to in order to get the task done. The conversation was recorded on a portable voice recorder.

Coding

From the recordings, the speakers’ words were transcribed and the target object descriptions were categorized into three kinds: bare names (e.g., “Pick up the plate, please.”), scalar-modified expressions (e.g., “Pick up the small plate, please.”), and errors, in which the participant asked his or her partner to pick up the wrong object.

Results and discussion

When the partners had common ground, the participants were highly sensitive to referential context (Fig. 2). Speakers typically produced a bare noun when there was only one object (e.g., plate, 93.52 %) but produced a scalar-modified noun phrase when two different-sized objects of the same kind were in common ground (e.g., small plate, 73.15 %). In contrast, in the privileged-ground condition, the participants used a bare noun (50.00 %) or a scalar-modified expression (46.30 %) roughly equally, suggesting that both common ground and privileged ground influenced their utterance designs.

Percentages of target descriptions using adjectives in Experiment 1

The data were analyzed with a mixed-effects model (see Baayen, Davidson & Bates, 2008) with random intercepts for both subjects and items; the use of a size adjective on each individual trial was treated as a binary dependent measure.Footnote 1 Two orthogonal contrasts were used to code condition: The first compared the one-object condition with the two-object and two-object-privileged conditions, which revealed that modification rates were significantly lower in the one-object condition (b = −6.36, SE = 0.91, p < .01; see Table 1). The second contrast compared the two-object and two-object-privileged conditions, which revealed that participants used significantly fewer adjectives when the competitor was privileged (b = 1.86, SE = 0.37, p < .01).

This experiment replicates the previous findings of moderate audience design in a new participant population and language (Korean) and sets the stage for our investigation of the role of speaker goals in audience design in Experiment 2. Furthermore, the results of Experiment 1 suggest that in language production, interference from one’s own privileged knowledge may reflect a standard, rather than a culturally determined (e.g., Wu & Keysar, 2007), component of language production. In Experiment 2, we explored whether privileged interference is modulated by speaker goals.

Experiment 2

In Experiment 2, we examined whether a speaker’s sensitivity to the perspective status of competitor objects is influenced by utterance goals (Searle, 1969)—specifically, informing and requesting. We hypothesized that speakers would be more likely to design expressions with respect to common ground when requesting, as the addressee must interpret the speaker’s message precisely in order to complete the request. In contrast, interpretation of information in the absence of some explicit behavioral goal (e.g., to move something) may afford less precise—that is, “good enough”—understanding (e.g., Ferreira, Bailey & Ferraro, 2002). This hypothesis is motivated by a view of language use according to which multiple information sources constrain processing—crucially, including what the user is trying to accomplish with his or her language (Brown-Schmidt & Hanna, 2011).

Method

Participants

A total of 30 pairs of students at Seoul National University, who had not participated in Experiment 1, participated in return for payment. The pairs were friends; one participated as speaker, the other as addressee. While our analyses focused on the speaker’s role, both participants were led to believe that they played key roles.

Materials

The materials were similar to those of Experiment 1. Each participant received 11 objects per set, with six critical objects (three targets and three competitors), plus five distractors. The participants were presented with 18 critical and 18 filler trials. In addition, unlike in Experiment 1, the target was the larger of the two competitor objects on half of the trials, and the smaller on the other half. Pairs of critical objects were placed near each other so that participants could easily identify the two objects and appreciate that their perspective conflicted with their partner’s. The critical objects were rotated across the critical conditions on three lists.

Procedure

The procedure was similar to that of Experiment 1. Two manipulations were used: common ground (three conditions, identical to those of Exp. 1) and utterance goal (informing vs. requesting). On informing trials, the experimenter was the agent moving the objects, and the speaker provided information to the addressee about where the objects would be moved before the experimenter moved them (e.g., “The experimenter will move the plate to the left”). On requesting trials, the speaker asked the addressee to move objects (e.g., “Can you move the plate to the left?”), and the addressee, rather than the experimenter, moved the object. The common-ground conditions were manipulated within subjects, and utterance goal was manipulated between subjects. Participants were randomly assigned to the goal conditions, and items were counterbalanced. Finally, unlike in Experiment 1, the participants did not switch roles with each other—the speakers and listeners continuously played their respective roles throughout the entire experiment.

Coding

The coding of scalar terms was identical to that of Experiment 1. Additionally, the speaker’s spatial language was categorized according to whether it was produced from the speaker’s perspective (e.g., “right” = speaker’s right) or the addressee’s perspective (e.g., “right” = addressee’s right).

Results and discussion

Modification

When perspectives differed (two-object-privileged condition), the utterance goal modulated referring, with modification rates of 36.67 % and 60.00 % in the requesting and informing conditions, respectively. The data were analyzed using a mixed-effects model with random intercepts for items and the empirical logit of size modification rate as the dependent measure, estimated for each participant and condition separately. While responses were binary (i.e., modified vs. not modified), aggregation via empirical logit was necessary because the modification rate in the one-object condition was exactly 0 % (no participant modified on any trial). This was problematic for the mixed-effects log odds model because there was no variance in that condition, making it impossible to model the random effects. In such situations, Agresti (2002) recommended empirical logit transformation, the approach that we have taken here, instead of log odds.

The results of this analysis replicated those of Experiment 1, with significantly lower modification rates in the one-object condition than in the two-object and two-object-privileged conditions, and less modification in the two-object-privileged condition than in the two-object condition (ps < .0001; see Fig. 3 and Table 2).Footnote 2 Importantly, speaker goal significantly interacted with the perspective effect (two-object vs. two-object-privileged, p < .01). Follow-up analyses determined that the interaction was due to a stronger perspective effect when speakers requested (b = 1.3045, p < .05) rather than informed (b = 0.6624, p < .05), suggesting that when speakers were in a situation in which they had to ask for something, they were more likely to avoid unnecessary and potentially confusing adjectives (see Wardlow Lane & Ferreira, 2008). In contrast, there was no effect of goal when perspectives were the same (one-object and two-object conditions, ps > .9), demonstrating that the goal manipulation did not simply change speakers’ overall motivation in the task or attention to utterance form.

Percentages of target descriptions using adjectives in Experiment 2. Utterance goal (informing vs. requesting) was manipulated between subjects

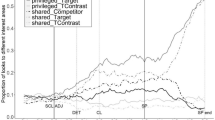

Spatial language

The analysis of spatial language showed a further effect of goals (Fig. 4). Recall that the participants faced each other; thus, the speaker’s egocentric right was the addressee’s egocentric left. We observed a significant effect of goal on the use of egocentric spatial language (b = 0.5738, SE = 0.2816, p < .01; see Table 3)Footnote 3: When requesting, speakers always adopted the addressee’s perspective, using expressions such as “on your left” when giving directions, whereas when informing, five of the 15 participants consistently used egocentric spatial terms designed from their own perspective. This result adds to the evidence that the process of tailoring an utterance for the addressee’s needs depends on what the speaker is trying to accomplish with an utterance.

Percentages of adopting addressee’s perspective (e.g., “on your left”) in spatial language in Experiment 2. Utterance goal (informing vs. requesting) was manipulated between subjects

A final consideration is that perhaps these results were due to low engagement in the informing task. We suspect that this is unlikely. In fact, error rates on the informing and requesting trials showed the opposite pattern, with seven errors when requesting and two when informing. Thus, the increased use of common ground when requesting was likely due to differences in the relevance of perspective to goals.

General discussion

In Experiment 1, we examined whether speakers would use scalar-modified referential expressions even when a scalar-contrast object was not visible to the addressee. When critical objects were in common ground, the participants produced a bare noun when there was only one object, but produced a noun phrase with a scalar adjective when there were two mutually visible different-sized objects of the same kind. In contrast, in the privileged condition, the competitor object was blocked from the addressee’s view, and speakers referred to the target with bare nouns on half of the trials. The fact that adjectives were used significantly less often when the competitor was privileged demonstrates sensitivity to common ground in utterance design. However, common ground was not a complete constraint on production—after all, speakers used adjectives that were unnecessary from the addressee’s perspective on half of the trials. These findings demonstrate—in a new paradigm and population—that information from both the speaker’s and addressee’s perspectives influences production.

After previous work with individuals from an interdependent culture (e.g., Wu & Keysar, 2007), we might have expected better use of common ground in this study, according to the assumption that our Korean sample was similar to Wu and Keysar’s Chinese sample in terms of being less individualistic (see Oyserman, Coon & Kemmelmeier, 2002, for a critical discussion and meta-analysis of this assumption). After all, Wu and Keysar found that in a comprehension task, Chinese, but not American, participants showed no significant interference from privileged lexical competitors, an effect attributed to the interdependence of Chinese culture. Why then, did our Korean participants fail to completely suppress privileged objects? One possibility is that in language production (unlike comprehension), the speaker’s privileged perspective is always relevant, as speaking often involves imparting new, previously privileged information to the addressee.

The results of Experiment 2 provide new, key evidence that utterance goals influence a speaker’s sensitivity to perspective. When critical objects were in common ground, goals played little role in referring, and the results were similar to those of Experiment 1. In contrast, when the competitor was privileged, the percentage of bare-noun responses (the appropriate response, from the addressee’s perspective) was significantly higher when speakers were requesting versus informing.

Why were speakers more sensitive to perspective when requesting? Here we suggest that when one’s goal is to make a request, it is more critical that the addressee interpret the speaker’s message precisely, in order for the requested action to be carried out correctly. In contrast, when informing, even if the addressee does not understand the speaker’s meaning precisely, this would not likely have direct influence on the speaker. In some sense, then, the heightened sensitivity to addressee perspective when the goal is to request is a form of egocentrism for goals: When the speaker wants an addressee to do something, he or she takes extra care to make sure that the request is understood. Interestingly, this “egocentric” goal increases the speaker’s tendency to take the perspective of the addressee.

The findings presented here provide initial evidence for this view. When a speaker makes a request, the addressee’s perspective has a stronger influence on the utterance form than when the speaker informs the addressee. Thus, the relevance of the addressee’s perspective to the utterance goals circumscribes the degree of audience design. These results allow for two important conclusions: First, the addressee’s ability to uniquely identify the intended referent is not necessary for communicative success. Instead, communicative success must be interpreted with respect to the speaker’s goals. Here, we have shown that the addressee’s ability to uniquely identify is less relevant when the listener is being informed. Second, the present findings suggest that audience design failures may say more about whether the listener’s unique perspective is, in fact, relevant to the communicative goals, rather than about the ability of speakers to engage in audience design. Findings of audience design failures in situations in which audience design was not necessary to the communicative goals (e.g., cases in which inaccurate understanding on the addressee’s part would have no effect on the task goals) are likely to be uninformative about the ability of speakers to engage in audience design.

Current models of the role of perspective in language production propose that the addressee’s needs are only relevant at a delayed stage of processing (Horton & Keysar, 1996), or include the addressee’s needs as one of many probabilistic constraints (Heller et al., 2012). The results of the present research paint a much more complex picture. How might our findings be accommodated within existing models of audience design? Within Horton and Keysar’s two-stage model, communicative goals might determine whether or not the initial egocentric utterance plan is revised, and perspective considered. If so, this could explain why, according to this model, speakers do not always engage in audience design, even in situations like those of the present experiments, in which the lack of time pressure provided more than enough time to revise perspective-inappropriate expressions. Within a constraint-based framework, the present findings suggest that goals modulate which constraints are relevant to the current linguistic processes, again offering an explanation for why speakers sometimes fail to use readily available information about perspective.

In conclusion, our results show that even when speakers are not under time pressure, common ground is not an absolute constraint on production. However, common ground does have clear and consistent effects. More importantly, we have demonstrated that understanding how and when common ground guides referring will crucially require an appreciation of what the speaker is trying to do with an utterance (i.e., Searle, 1969). Here we have taken a first step in this direction, demonstrating that the relevance of the addressee’s perspective to the utterance form is circumscribed by the speaker’s utterance goals.

Notes

On consideration of the deviance test statistic and the Akaike information criterion (Akaike, 1974), adding random slopes did not improve model fit. Furthermore, models with random slopes generated the same pattern of significance for the fixed effects. For parsimony, the simpler model is presented here. In addition, supplemental analyses using an ANOVA approach yielded an identical pattern of results, with significant effects for both the first comparison (one-object vs. two-object and two-object-privileged conditions) [F 1(1, 16) = 29.686, MSE = 574.165, p < .01; F 2(1, 16) = 92.698, MSE = 216.503, p < .01] and the second comparison (two-object vs. two-object-privileged condition) [F 1(1, 16) = 8.798, MSE = 737.564, p < .01; F 2(1, 16) = 18.787, MSE = 345.407, p < .01].

Supplemental analyses using an ANOVA approach yielded an identical pattern of results, with a significant effect for condition [F 1(2, 27) = 86.151, MSE = 0.041, p < .01; F 2(2, 15) = 120.586, MSE = 259.150, p < .01] and an interaction between goal and the perspective effect [F 1(2, 27) = 5.020, MSE = 0.041, p < .05; F 2(2, 15) = 3.623, MSE = 938.889, p = .065].

An ANOVA approach provided an identical pattern of results, with significant effects for goal on the use of egocentric spatial language [F 1(1, 28) = 4.054, MSE = 1243.533, p = .054; F 2(1, 16) = 285.558, MSE = 23.675, p < .01].

References

Agresti, A. (2002). Categorical data analysis (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Wiley-Interscience.

Akaike, H. (1974). A new look at the statistical model identification. IEEE Transactions on Automatic Control, AC-19, 716–723. doi:10.1109/TAC.1974.1100705

Baayen, R. H., Davidson, D. J., & Bates, D. M. (2008). Mixed-effects modeling with crossed random effects for subjects and items. Journal of Memory and Language, 59, 390–412. doi:10.1016/j.jml.2007.12.005

Brown-Schmidt, S., Gunlogson, C., & Tanenhaus, M. K. (2008). Addressees distinguish shared from private information when interpreting questions during interactive conversation. Cognition, 107, 1122–1134. doi:10.1016/j.cognition.2007.11.005

Brown-Schmidt, S., & Hanna, J. E. (2011). Talking in another person’s shoes: Incremental perspective-taking in language processing. Dialog and Discourse, 2, 11–33.

Clark, H. H. (1996). Using language. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press.

Deutsch, W. (1976). Sprachliche Redundanz und Objekt Identifikation. Marburg, Germany: Unpublished dissertation, University of Marburg.

Epley, N., Morewedge, C. K., & Keysar, B. (2004). Perspective taking in children and adults: Equivalent egocentrism but differential correction. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 40, 760–768.

Ferreira, F., Bailey, K. G. D., & Ferraro, V. (2002). Good-enough representations in language comprehension. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 11, 11–15.

Hanna, J. E., Tanenhaus, M. K., & Trueswell, J. C. (2003). The effects of common ground and perspective on domains of referential interpretation. Journal of Memory and Language, 49, 43–61.

Heller, D., Gorman, K., & Tanenhaus, M. K. (2012). To name or describe: Shared knowledge affects referential form. TopiCS.

Horton, W. S. (2007). The influence of partner-specific memory associations on language production: Evidence from picture naming. Language and Cognitive Processes, 22, 1114–1139.

Horton, W. S., & Keysar, B. (1996). When do speakers take into account common ground? Cognition, 59, 91–117. doi:10.1016/0010-0277(96)81418-1

Keysar, B., Barr, D. J., Balin, J. A., & Paek, T. S. (1998). Definite reference and mutual knowledge: Process models of common ground in comprehension. Journal of Memory and Language, 39, 1–20.

Keysar, B., Lin, S., & Barr, D. J. (2003). Limits on theory of mind use in adults. Cognition, 89, 25–41.

Nadig, A. S., & Sedivy, J. C. (2002). Evidence of perspective-taking constraints in children’s on-line reference resolution. Psychological Science, 13, 329–336.

Nadig, A., Vivanti, G., & Ozonoff, S. (2009). Object descriptions under different communicative demands: How do children with and without autism adapt? Autism Research, 2, 1–14.

Oyserman, D., Coon, H. M., & Kemmelmeier, M. (2002). Rethinking individualism and collectivism: Evaluation of theoretical assumptions and meta-analyses. Psychological Bulletin, 128, 3–72. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.128.1.3

Searle, J. (1969). Speech acts. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Sedivy, J. (1999). Examining the discourse-based properties of adjectives in on-line semantic processing. New York, NY: Paper presented at the 12th Annual CUNY Conference on Human Sentence Processing.

Tanenhaus, M., & Trueswell, J. (1995). Sentence comprehension. In J. Miller & P. Eimas (Eds.), Handbook of cognition and perception: Vol. 11. Speech and language. San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Wardlow Lane, L., & Ferreira, V. S. (2008). Speaker-external versus speaker-internal forces on utterance form: Do cognitive demands override threats to referential success? Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 34, 1466–1481.

Wardlow Lane, L., Groisman, M., & Ferreira, V. S. (2006). Don’t talk about pink elephants! Speakers’ control over leaking private information during language production. Psychological Science, 17, 273–277.

Wardlow Lane, L., & Liersch, M. J. (2012). Can you keep a secret? Increasing speakers’ motivation to keep information confidential yields poorer outcomes. Language and Cognitive Processes.

Wu, S., & Keysar, B. (2007). The effect of communication overlap on communication effectiveness. Cognitive Science, 31, 169–181.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Yoon, S.O., Koh, S. & Brown-Schmidt, S. Influence of perspective and goals on reference production in conversation. Psychon Bull Rev 19, 699–707 (2012). https://doi.org/10.3758/s13423-012-0262-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.3758/s13423-012-0262-6