Abstract

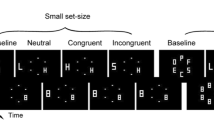

The item-specific proportion congruence (ISPC) effect refers to the attenuation of interference for mostly incongruent relative to mostly congruent items. In the present study, qualitatively different ISPC effects were observed in letter- and arrow-based flanker tasks despite their common use of the original two-item set design. Consistent with the predictions of the dual item-specific mechanisms account, contingency-driven ISPC effects were observed when stimuli were used that attracted attention to the irrelevant dimension (Experiments 1, 3, and 6), whereas control-driven ISPC effects were observed when attention was attracted to the relevant dimension (Experiments 2, 4, and 5). The evidence for control-driven ISPC effects in the two-item set design (1) challenges the contingency account, which claims that ISPC effects are solely contingency-driven, and (2) supports an expanded definition of cognitive control that includes fast and flexible adjustments that minimize attention to distractors upon encountering stimuli that have previously been associated with a history of conflict.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Frequency accounts (e.g., Logan, 1988) have therefore been evaluated as explanations of the ISPC effect. A major piece of evidence arguing against such accounts is the results of the process-dissociation procedure showing that ISPC selectively influences the word-reading process (Jacoby et al., 2003). If frequency was driving the effect, this procedure should have revealed an influence on both the color and word processes, since it is particular combinations that are more or less frequent.

In prior studies (Bugg & Hutchison, 2013; Bugg et al., 2011a), the dual-ISM account was termed the “item-specific control account.” The new label was adopted to better capture the account’s position that item-specific control and contingency learning produce ISPC effects, albeit under different conditions, and to minimize potential confusion between the terms “item-specific control account” and “item-specific control.”

It is possible that the symmetrical pattern suggested to characterize contingency learning in the study of Jacoby et al. (2003; see Schmidt & Besner, 2008) resulted from the operation of a contingency-learning mechanism on MC-congruent trials and an item-specific control mechanism on MI-incongruent trials. If so, the ISPC pattern that characterizes contingency learning may be an asymmetrical one in which ISPC selectively speeds MC-congruent, relative to MI-congruent, trials, including in the original two-item set design (see Bugg et al., 2011a, Experiment 3, for evidence of this pattern in a variant of the two-item sets design in which words from one set appeared with pictures from that set and the opposite set such that only MC-congruent trials were of the high contingency type).

The tectonic theory of Melara and Algom (2003) was formulated in the context of Stroop tasks where dimensions referred to the relevant (color) and irrelevant (word) information. I am generalizing the theoretical assumptions to the flanker task, where the relevant dimension is the central target and the irrelevant dimension refers to the peripheral flankers.

The overall slowed responding in Experiment 1, relative to Experiment 2, speaks to a recent revision of the contingency account. Schmidt (2013a) noted that Schmidt and Besner (2008) were mistaken in asserting that a contingency mechanism would not produce a stronger effect on incongruent trials. He suggested that contingency effects could actually be larger for incongruent than for congruent trials because incongruent trials take longer to process and, therefore, contingency has more time to affect behavior. Given that it took ~100 ms longer on average to respond to incongruent trials in Experiment 1 than in Experiment 2, on this view, the effect of ISPC on incongruent trials should have been stronger in Experiment 1 than in 2 if a contingency mechanism were operative in both experiments (which was not found).

To evaluate whether stimulus type-specific Gratton effects contributed to the qualitatively different ISPC patterns across Experiments 1 and 2, a four-way analysis was performed with previous PC, previous trial type, current PC, and current trial type as factors. There was no evidence for a stimulus type-specific Gratton effect in either experiment (i.e., no interactions of previous PC or previous trial type with the ISPC effect, nor a four-way interaction, ps > .10).

The author is grateful to an anonymous reviewer who suggested the perceptual tuning account and proposed the idea of examining alternative letter sets and using an incompatible stimulus–response assignment in the arrow-based flanker task to examine the account.

One might wonder why this prediction was not (also) tested in the context of the letter-based flanker paradigm used in Experiment 5. I thought it would be difficult for participants to coordinate an incompatible stimulus–response assignment with the stimulus–response translation demands that were already evoked by the task, and this difficulty would likely exacerbate RT slowing and increase error variance.

It is unclear whether the contingency account would have predicted a contingency-driven ISPC effect in Experiment 6 given the use of an incompatible stimulus–response rule, which might interfere with typical contingency learning processes.

References

Atalay, N. B., & Misirlisoy, M. (2012). Can contingency learning alone account for item-specific control? Evidence from within- and between- language ISPC effects. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 38, 1578–1590.

Blais, C., & Bunge, S. (2010). Behavioral and neural evidence for item-specific performance monitoring. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 22, 2758–2767.

Blais, C., Robidoux, S., Risko, E. F., & Besner, D. (2007). Item-specific adaptation and the conflict monitoring hypothesis: A computational model. Psychological Review, 114, 1076–1086.

Botvinick, M. M., Braver, T. S., Barch, D. M., Carter, C. S., & Cohen, J. D. (2001). Conflict monitoring and cognitive control. Psychological Review, 114, 1076–1086.

Braver, T.S., Gray, J.R., & Burgess, G.C. (2007). Explaining the many varieties of working memory variation: Dual mechanisms of cognitive control. In A.R.A. Conway, C. Jarrold, M.J. Kane, A. Miyake, & J.N. Towse (Eds.), Variation in working memory (pp. 76–106). Oxford University Press.

Bugg, J. M. (2012). Dissociating levels of cognitive control: The case of Stroop interference. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 21, 302–309.

Bugg, J. M. (2014a). Evidence for the sparing of reactive cognitive control with age. Psychology and Aging, 29, 115–127.

Bugg, J. M. (2014b). Conflict triggered top-down control: Default mode, last resort, or no such thing? Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 40, 567–587.

Bugg, J. M., & Chanani, S. (2011). List-wide control is not entirely elusive: Evidence from picture-word Stroop. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 18, 930–936.

Bugg, J. M., & Crump, M. J. C. (2012). In support of a distinction between voluntary and stimulus-driven control: A review of the literature on proportion congruent effects. Frontiers in Psychology: Cognition, 3, 1–16.

Bugg, J. M., & Hutchison, K. A. (2013). Converging evidence for control of color-word Stroop interference at the item level. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 39, 433–449.

Bugg, J. M., Jacoby, L. L., & Chanani, S. (2011a). Why it is too early to lose control in accounts of item-specific proportion congruency effects. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 37, 844–859.

Bugg, J. M., Jacoby, L. L., & Toth, J. (2008). Multiple levels of control in the Stroop task. Memory & Cognition, 36, 1484–1494.

Bugg, J. M., McDaniel, M. A., Scullin, M. K., & Braver, T. S. (2011b). Revealing list-level control in the Stroop task by uncovering its benefits and a cost. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 37, 1595–1606.

Chajut, E., Schupak, A., & Algom, D. (2009). Are spatial and dimensional attention separate? Evidence from Posner, Stroop, and Eriksen tasks. Memory & Cognition, 37, 924–934.

Corballis, P. M., & Gratton, G. (2003). Independent control of processing strategies for different locations in the visual field. Biological Psychology, 64, 191–209.

Crump, M. J., Gong, Z., & Milliken, B. (2006). The context-specific proportion congruent Stroop effect: Location as a contextual cue. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 13, 316–321.

Crump, M. J. C., & Milliken, B. (2009). The flexibility of context-specific control: Evidence for context-driven generalization of item-specific control. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 62, 1523–1532.

Dishon-Berkovits, M., & Algom, D. (2000). The Stroop effect: It is not the robust phenomenon that you have thought it to be. Memory & Cognition, 28, 1437–1449.

Eriksen, B. A., & Eriksen, C. W. (1974). Effects of noise letters upon the identification of a target letter in a nonsearch task. Perception & Psychophysics, 16, 143–149.

Fraisse, P. (1969). Why is naming longer than reading? Acta Psychologica, 30, 96–103.

Gratton, G., Coles, M. G. H., & Donchin, E. (1992). Optimizing the use of information: Strategic control of activation and responses. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 121, 480–506.

Hutchison, K. A. (2011). The interactive effects of list-based control, item-based control, and working memory capacity on Stroop performance. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 37, 851–860.

Jacoby, L. L., Lindsay, D. S., & Hessels, S. (2003). Item-specific control of automatic processes: Stroop process dissociations. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 10(3), 638–644.

King, J. A., Korb, F. M., & Egner, T. (2012). Priming of control: Implicit contextual cueing of top-down attentional set. The Journal of Neuroscience, 32, 8192–8200.

Kornblum, S., & Lee, J. (1995). Stimulus response compatibility with relevant and irrelevant stimulus dimensions that do and do not overlap with the response. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception & Performance, 21, 855–875.

Lehle, C., & Hübner, R. (2008). On-the-fly adaptation of selectivity in the flanker task. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 15, 814–818.

Logan, G. D. (1988). Toward an instance theory of automatization. Psychological Review, 95, 492–527.

Logan, G. D., & Zbrodoff, N. J. (1979). When it helps to be misled: Facilitative effects of increasing the frequency of conflicting stimuli in a Stroop-like task. Memory & Cognition, 7, 166–174.

Lowe, D., & Mitterer, J. O. (1982). Selective and divided attention in a Stroop task. Canadian Journal of Psychology, 36, 684–700.

Melara, R. D., & Algom, D. (2003). Driven by information: A tectonic theory of Stroop effects. Psychological Review, 110, 422–471.

Melara, R. D., & Mounts, J. R. W. (1993). Selective attention to Stroop dimensions: Effects of baseline discriminability, response mode, and practice. Memory & Cognition, 21, 627–645.

Mattler, U. (2006). Distance and ratio effects in the flanker task are due to different mechanisms. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 59, 1745–1763.

Miller, J. (1987). Priming is not necessary for selective-attention failures: Semantic effect of unattended, unprimed letters. Perception & Psychophysics, 41, 419–434.

Schmidt, J. R., & Besner, D. (2008). The Stroop effect: Why proportion congruence has nothing to do with congruency and everything to do with contingency. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, & Cognition, 34, 514–523.

Schmidt, J. R. (2013a). The parallel episodic processing (PEP) model: Dissociating contingency and conflict adaptation in the item-specific proportion congruent paradigm. Acta Psychologica, 142, 119–126.

Schmidt, J. R. (2013b). Questioning conflict adaptation: Proportion congruent and Gratton effects reconsidered. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 20, 615–630.

Schmidt, J. R. (2014). Contingencies and attentional capture: The importance of matching stimulus informativeness in the item-specific proportion congruent task. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, 540. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00540

Shedden, J. M., Milliken, B., Watter, S., & Monteiro, S. (2013). Event-related potentials as brain correlates of item specific proportion congruent effects. Consciousness and Cognition, 22, 1442–1455.

Verguts, T., & Notebaert, W. (2008). Hebbian learning of cognitive control: Dealing with specific and nonspecific adaptation. Psychological Review, 115, 518–525.

Virzi, R. A., & Egeth, H. E. (1985). Toward a translational model of Stroop interference. Memory & Cognition, 13, 304–319.

Wendt, M., Kluwe, R. H., & Vietze, I. (2008). Location-specific versus hemisphere-specific adaptation of processing selectivity. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 15, 135–140.

Wendt, M., & Luna-Rodriguez, A. (2009). Conflict-frequency affects flanker-interference. Experimental Psychology, 56, 206–217.

Author’s Note

The author is grateful to Keith Hutchison for providing feedback on a previous version of the manuscript and for helpful discussion of the differences between letter-based and arrow-based flanker paradigms. The author thanks Maxwell Coll, Molly Evans, Madeline Kleiner, Joshua Kim, Henna Mishra, Simran Sahni, Leah Sutton, and Vivian Tao for assisting with data collection and coding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bugg, J.M. The relative attractiveness of distractors and targets affects the coming and going of item-specific control: Evidence from flanker tasks. Atten Percept Psychophys 77, 373–389 (2015). https://doi.org/10.3758/s13414-014-0752-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.3758/s13414-014-0752-x