Abstract

Focused visual attention can be shifted between objects and locations (attentional orienting) or expanded and contracted in spatial extent (attentional focusing). Although orienting and focusing both modulate visual processing, they have been shown to be distinct, independent modes of attentional control. Objects play a central role in visual attention, and it is known that high-level object representations guide attentional orienting. It not known, however, whether attentional focusing is driven by low-level object representations (which code object size in terms of retinotopic extent) or by high-level representations (which code perceived size). We manipulated the perceived size of physically identical objects by using line drawings or photographs that induced the Ponzo illusion, in a task requiring the detection of a target within these objects. The distribution of attention was determined by the perceived size and not by the retinotopic size of an attended object, indicating that attentional focusing is guided by high-level object representations.

Similar content being viewed by others

The complexity of the sensory environment requires a cognitive mechanism that rapidly and flexibly prioritizes relevant information for visual processing. Selective visual attention serves this function: it can be shifted rapidly between locations (Posner, 1980; Weichselgartner & Sperling, 1987) not only reflexively, in response to salient events and objects (Jonides & Yantis, 1988; Theeuwes, 1992; Yantis & Jonides, 1984), but also voluntarily on the basis of task demands and goals (Jonides, 1981; Nakayama & Mackeben, 1989). The focus of attention can also be expanded or contracted in spatial extent to encompass large or small objects, respectively (e.g., Castiello & Umiltà, 1990; Egeth, 1977; Eriksen & Yeh, 1985; LaBerge, 1983, 1995; Maringelli & Umiltà, 1998). Although great strides have been made in understanding the spatial orienting of attention, considerably less is known about the determinants of the spatial extent, or breadth, of focal attention.

The process of expanding or contracting the focus of attention—here referred to as attentional focusing—is distinct and independent from the shifting of attention. The two processes, for example, can be triggered independently (Maringelli & Umiltà, 1998), each follows a distinct time course (Benso, Turatto, Mascetti, & Umiltà, 1998; Jefferies & Di Lollo, 2009; Weichselgartner & Sperling, 1987), and each is affected differently by training (Turatto, Benso, & Umiltà, 1999), by neurodevelopmental disorders (e.g., Facoetti et al., 2003; Facoetti, Paganoni, Turatto, Marzola, & Mascetti, 2000; Ronconi, Gori, Ruffino, Molteni, & Facoetti, 2013), and by normal ageing (e.g., Greenwood, Parasuraman, & Haxby, 1993; Jefferies, Roggeveen, et al., 2013; Lincourt, Folk, & Hoyer, 1997).

Attentional focusing has been demonstrated clearly in many behavioral studies (e.g., Castiello & Umiltà, 1990; Egeth, 1977; Eriksen & Yeh, 1985; Eriksen & St. James, 1986; LaBerge & Brown, 1986; Maringelli & Umiltà, 1998; Posner, 1980), and more recent neuroimaging studies provide strong converging evidence. N. G. Müller, Bartelt, Donner, Villringer, and Brandt (2003), for example, showed that the extent of the activated visual cortex increases with the size of the attentional focus, and this size-related modulation of neural activity provides strong neurophysiological evidence for attentional focusing. Neuroimaging studies have also indicated that different brain regions may be involved with different aspects of attentional focusing (e.g., Chen, Marshall, Weidner, & Fink, 2009; Ronconi, Basso, Gori, & Facoetti, 2014).

Attentional focusing is often reflexive; there is evidence, for example, that if the onset of a small object is followed by the onset of a larger object centered on the same location, the focus of attention expands reflexively to encompass the larger object. This is true even if expanding the attentional focus is obviously detrimental to the task and impairs task performance (Turatto et al., 2000). Although reflexive attentional focusing facilitates the processing of objects of various sizes, there is a trade-off between the spatial extent of focal attention and visual processing efficiency within the attended region. This trade-off was perhaps most clearly demonstrated by Castiello and Umiltà (1990), who presented observers with a square cue that subtended 1°, 2°, or 3° of visual angle. The abrupt onset of the cue triggered a reflexive expansion or contraction of the attentional focus to match the size of the cue. Notably, response times (RTs) to targets appearing at locations within the cue were fastest when the cue was small and increased by about 15 ms with each 1° increase in the size of the cue. RTs to targets outside of the cue showed no attentional benefit, regardless of the size of the cue, showing that the focus of attention tightly encompassed each cue. The present experiments were predicated directly on the breadth–efficiency trade-off evidenced by the cue-size effect of Castiello and Umiltà.

The breadth–efficiency trade-off influences various aspects of visual cognition, including not only the speed and accuracy with which targets can be detected and discriminated (Barriopedro & Botella, 1998; Castiello & Umiltà, 1990; Eriksen & St. James, 1986; Eriksen & Yeh, 1985; Jefferies, Ghorashi, Kawahara, & Di Lollo, 2007; Maringelli & Umiltà, 1998; M. M. Müller, Malinowki, Gruber, & Hillyard, 2003; Turatto et al., 2000), but also contrast sensitivity (Hermann, Montaser-Kouhasari, Carrasco, & Heeger, 2010), and even the effective capacity of visual sensory memory (Gmeindl, Jefferies, & Yantis, 2014). Functional magnetic resonance imaging research has confirmed that the breadth–efficiency trade-off is reflected in the profile of activity in early, retinotopically mapped visual cortex: When the attentional focus is narrow, there is a strong increase in activity of a relatively small region of early visual cortex. When the attentional focus is broad, however, the area of visual cortex showing enhanced activity is of greater extent, but the degree of enhancement is attenuated (N. G. Müller et al., 2003; see also Chen et al., 2009). Although some factors that trigger attentional focusing have been identified—mood, for instance, causes the focus of attention to expand or contract (Fernandes, Koji, Dixon, & Aquino, 2011; Friedman & Förster, 2010; Rowe, Hirsh, & Anderson, 2007)—relatively little is known about the many stimulus factors that might modulate the breadth of attention. Of particular importance, it is not known how object representations guide attentional focusing.

Objects are essential determinants of the deployment of attention (e.g., Egly, Driver, & Rafal, 1994; Scholl & Pylyshyn, 1999; Serences, Schwarzbach, Courtney, Golay, & Yantis, 2004; Tipper, Driver, & Weaver, 1991) and are represented at multiple levels of visual processing. Low-level representations code the primitive visual features of an object, such as brightness and edge orientation, at the earliest stages of visual processing (e.g., Marr, 1982). Higher-level representations, on the other hand, incorporate information about context and object identity. The coding of an object’s properties—its size, for instance—can differ considerably across these levels of representation. For example, whereas the area of the retina subtended by an object can change as the object moves about in the world (causing changes to low-level representations of the object’s size), top-down influences on higher-level representations stabilize the object’s perceived size by taking into account perceived distance (a phenomenon known as size constancy). Conversely, an object’s perceived size can vary due to its environmental context, even when the size of the object’s retinal image remains the same, as illustrated in the classic Ponzo (1910) illusion.

Several studies have shown that high-level object representations take precedence over low-level representations in guiding the orienting of attention in visual search tasks (e.g., Enns & Rensink, 1990, 1991; He & Nakayama, 1992; Rensink & Cavanagh, 2004; Suzuki & Cavanagh, 1995; Wang, Cavanagh, & Green, 1994; see also Hochstein & Ahissar, 2002). Robertson and Kim (1999) provided one of the clearest demonstrations that high-level object representations play a critical role in the orienting of visual attention.

In their study, Robertson and Kim (1999) adapted the paradigm developed by Egly, Driver, and Rafal (1994) to investigate shifts of attention within and between objects. Egly et al. had presented two rectangles, one on either side of fixation. An abrupt-onset spatial cue appeared at one end of one of the rectangles, followed by a target. The target appeared at either the cued location or one of two uncued locations: the opposite end of the cued rectangle or the same end of the uncued rectangle. The rectangles were arranged such that the distance between ends of the cued rectangle was equal to the distance between the cued end of one rectangle and the nearest end of the other rectangle. Detecting the target at an uncued location in the cued rectangle required attention to be shifted to a new location, but did not require attention to be shifted to a new object; detecting the target in the uncued rectangle, however, required attention to be shifted an equal distance to a location in a different object. This design allowed for the measurement of the RT costs of shifting attention between locations both within the same object and across different objects. The results indicated that RTs increased significantly if attention had to be shifted to an uncued location within the cued object, and was even longer if attention had to be shifted to the uncued object.

Robertson and Kim (1999) adapted the Egly et al. (1994) paradigm to examine whether the perceived structural organization of a scene modulates the deployment of attention. In their experiment, they superimposed two vertical lines, one on either side of fixation, on a background that strongly induced the perception of depth. Although the two lines were physically identical in length, the Ponzo illusion caused the line that appeared to be farther away to be perceived as longer than the line that appeared to be closer. The rest of their paradigm followed directly from that of Egly, Driver, and Rafal: A transient, abrupt-onset cue appeared at the end of one line, followed by the target. The target appeared at either the cued location, the uncued end of the cued line, or an uncued location in the uncued line. Replicating the findings of Egly, Driver, and Rafal, RTs were significantly faster to targets appearing at within-object uncued locations than to targets appearing at between-object uncued locations. More importantly for the present study, Robertson and Kim also found that the RT cost associated with shifting attention within and between objects varied on the basis of the perceived size of the line. Robertson and Kim concluded that retinal representations of objects and space are insufficient to account for all spatial orienting effects; instead, high-level object representations and the perceived structure of a scene (including depth and distance information) play a vital role.

As we outlined earlier, focusing and orienting are independent aspects of attentional control, and each plays a vital role in visual cognition and performance. Although Robertson and Kim’s (1999) study shows clearly that attentional orienting is guided by high-level object representations, it is unknown to what extent attentional focusing is driven by high-level or low-level object representations. The experiment of Egly, Driver, and Rafal (1994) was designed specifically to investigate shifts of attention within and between objects, and is not well suited to examining attentional focusing for several reasons. First, the abrupt onset of a spatial cue at one end of an object triggers a reflexive shift of focal attention to that location. Furthermore, since the cue is valid on 75 % of trials, it is beneficial for the observer to shift attention to the cued location. In other words, this paradigm couples a strong reflexive trigger to shift attention with an endogenous motivation to instigate the shift. The observer has no reason to expand the focus of attention to encompass the entire object rather than shifting attention to the cued location. Indeed, the data themselves are consistent with an attention-shifting interpretation: If the attentional focus had expanded to encompass the entire object, one would expect approximately equivalent RTs to targets at either end of the cued object (since both locations would fall equally within the attentional focus). The RTs from both Egly et al.’s and Robertson and Kim’s studies, however, were significantly faster to targets appearing at the cued than at the uncued location in the cued object. This pattern of results, although perfectly consistent with an attentional focus that has shifted to the cued end of the object, is inconsistent with a broadly expanded focus of attention.

Although Robertson and Kim’s (1999) study showed that an object’s perceived size influences attentional orienting, it is still not known whether perceived size also modulates attentional focusing. The present study was designed specifically to identify the level of object representation that drives attentional focusing and to fill this gap in the visual-attention literature. We employed the Ponzo illusion to dissociate an object’s perceived size from its retinal image size. Our task encouraged the observer to attend to the entire object (in order to study attentional focusing) rather than to shift attention to part of the object. If attentional focusing is driven by low-level object representations, the size of the attentional focus would be yoked to the retinal image size of the object and would not vary on the basis of the object’s perceived size. If, on the other hand, attentional focusing is driven by higher-level object representations and is subject to the influences of contextual information, then the focus of attention would expand or contract to match the perceived size of the object.

Experiment 1a

To assess the spatial extent of focal attention, Castiello and Umiltà (1990) developed the cue-size paradigm. In this paradigm, the spatial extent of the focus of attention is manipulated by varying the size of a spatial cue (e.g., a square). Castiello and Umiltà found that the RT to the onset of a target was slowed by approximately 15 ms for each 1° increase in the size of the cue. This change in RT as a function of cue size—the cue-size effect—therefore indexes the breadth of the focus of attention. The cue-size effect is a robust phenomenon observed not only with simple detection tasks (e.g., Castiello & Umiltà, 1990; Maringelli & Umiltà, 1998), but also with target discrimination tasks (e.g., Barriopedro & Botella, 1998; Turatto et al., 2000), with a variety of cue shapes (Galera, von Grünau, & Panagopoulos, 2005), and with a range of cue sizes from 1° to 9° of visual angle (Benso, Turatto, Mascetti, & Umiltà, 1998).

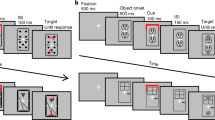

In testing whether attentional focusing is driven by high- or low-level object representations, we combined features of Castiello and Umiltà’s (1990) cue-size paradigm with a perceptual illusion to create objects that were physically identical but that differed in perceived size. Specifically, we superimposed physically identical rectangles on a simple line version of the Ponzo illusion background (see Fig. 1a), which produced a difference of ±15 % in the perceived sizes of the rectangles.Footnote 1 When the Ponzo illusion background was presented as in Fig. 1a (i.e., with the vanishing point on the right), a rectangle presented on the right appeared to be larger than one presented on the left; when the background was reversed, such that the vanishing point was on the left, a rectangle on the right appeared to be smaller than one presented on the left. According to the logic of Castiello and Umiltà, if attentional focusing is based on high-level representations, and the spatial extent of the focus of attention varies with the perceived size of an object, responses to targets appearing anywhere in the perceptually smaller rectangle should be faster than responses to targets appearing in the perceptually larger rectangle. If, on the other hand, attentional focusing is driven by low-level object representations, and the spatial extent of focal attention is therefore locked to the physical size of an attended object, RTs should be unaffected by differences in the perceived sizes of the rectangles.

(A) The Ponzo illusion used to induce perceptually different sizes of cues that were physically identical. (B) Sequence of events in a trial. The cues are illustrated as filled gray rectangles, but in the experiment they were blue. (C) Mean reaction times in Experiment 1a as a function of perceived cue size, collapsed across vanishing point direction and target location. (D) Stimuli used in Experiment 1b

Method

Observers

Twelve undergraduate students (nine males, three females, all right-handed; 19–24 years of age) at Johns Hopkins University participated for course credit. All participants reported normal or corrected-to-normal vision and were naïve as to the purpose of the experiment.

Apparatus and stimuli

The experiment was conducted in dimly lit individual testing rooms, in which participants were seated with their eyes 61 cm from a 17-in. CRT computer monitor set at 75 Hz. A chinrest was used to maintain a constant viewing distance. Stimulus presentation was controlled by a custom MATLAB v.6.5 script (The MathWorks, Natick, MA) using Psychophysics Toolbox v.2.54 (Brainard, 1997).

A black plus sign (0.25° × 0.25° of visual angle) was displayed in the center of the screen; participants were instructed to maintain fixation on the cross throughout each trial, and to ensure that they did so, the position of the participant’s right pupil was monitored continuously via a high-contrast closed-circuit video system by the experimenter, who flagged any trials in which an eye movement was detected. If a trial was flagged, a visual warning was displayed to the participant and that trial was excluded from the analysis.Footnote 2

The illusion-inducing background subtended 9.25° × 7°, centered on the fixation cross. The lines of the Ponzo illusion were dark gray, superimposed on a light gray background. The rest of the monitor was black. The rectangles (2° × 0.5°) were a solid blue color with a 1-pixel darker blue outline. The rectangles appeared 3.3° (center-to-center) to the left or right of fixation. The target was a filled black circle (0.3° in diameter).

Procedure

The illusion-inducing background appeared at the very beginning of the testing session and was present continuously, except during breaks. For half of the participants, the background appeared as in Fig. 1a (“vanishing point” on the right) for the first half of the testing session, and then appeared in the reverse direction (“vanishing point” on the left) for the rest of the trials. For the remaining participants, the order of presentation was reversed.

Each trial began with the appearance of the fixation cross, followed by a delay of 500, 600, or 700 ms. A single rectangle was then presented on each trial; on a randomly intermixed half of the trials, it was the perceptually smaller rectangle; on the other half of the trials, it was the perceptually larger rectangle. It is worth reiterating that the physical sizes of the rectangles were identical in all cases; the differences in size were purely perceptual. After a cue–target onset asynchrony (CTOA) of 450, 500, or 550 ms, the target appeared randomly at one of two locations—either in the top or the bottom quarter of the rectangle—and participants pressed the spacebar as soon as they detected the target’s onset. The target remained present on the screen until a response was made. On 12 % of the trials, no target appeared, and participants were to withhold their responses on these catch trials. Trials in which participants responded on a catch trial or prior to the target’s onset (anticipations) were flagged, and a warning appeared on the screen. Each participant completed a total of 480 trials.

Results and discussion

Approximately 2 % of the trials were discarded due to errors: 1.2 % for eye movements, 0.4 % for anticipations, and 0.6 % for responses on catch trials. In addition, any trials in which RTs fell two standard deviations above or below the mean were excluded, resulting in an additional 1.5 % of the trials being discarded.

The data were analyzed in a 2 (perceived rectangle size: large, small) × 2 (vanishing point location: left, right) × 2 (target location: top, bottom) repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA). The main effect of perceived rectangle size was significant, indicating that participants were reliably faster to detect the target when the rectangle was perceptually smaller than when it was perceptually larger [F(1, 11) = 8.7, p = .013, η 2 = .44; see Fig. 1c]. No other main effects or interactions were reliable. This illusory-cue-size effect provides evidence that the spatial extent of focal attention is not merely yoked to the physical extent of an attended object. Instead, the spatial extent of the focus of attention is also modulated by the object’s perceived size. In other words, attentional focusing is driven by high-level object representations.

It is worth nothing that the main effect of target location (top, bottom) was not significant [F(1, 11) = 0.87, p = .38] and that target location did not interact with any other variable: Vanishing Point Location × Target Location, F(1, 11) = 0.25, p = .61; Size × Location, F(1, 11) = 0.83, p = .38; Vanishing Point Location × Target Location × Size, F(1, 11) = 0.47, p = .83. As we discussed in the introduction, if the focus of attention expands or contracts to encompass the entire object, RTs should be roughly comparable at all locations within the object. The RTs in Experiment 1 were indeed comparable for targets in both locations within the object, confirming that the attentional focus encompassed the entire object.

Experiment 1b

In the version of the Ponzo illusion used in Experiment 1a, the density of the background lines surrounding the perceptually smaller rectangle was lower than the density of the lines surrounding the perceptually larger rectangle. It is possible, therefore, that some form of crowding could account for the observed RT differences. In Experiment 1b we examined this possibility by superimposing the rectangles on backgrounds of horizontal lines that provided no depth information, but that matched the average density of the backgrounds surrounding the perceptually smaller or larger rectangles in Experiment 1a (see Fig. 1d for an illustration). If line density contributed to the effect in Experiment 1a, RT differences as a function of background density should also be apparent in Experiment 1b.

Method

Observers

A group of 16 undergraduates (nine males, seven females, one left-handed; ages 19–34 years) at Johns Hopkins University participated for payment. All reported normal or corrected-to-normal vision and were naïve as to the purpose of the experiment.

Apparatus and stimuli

The details of the apparatus and stimulus presentation were identical to those in Experiment 1a, except as described above. Half of the participants completed the high-density block first, whereas the other half completed the low-density block first. Each participant completed 200 trials.

Results and discussion

The mean RTs were strikingly similar across all conditions: 352 (SD = 63.9) and 350 ms (SD = 79.7) for the high- and low-density backgrounds, respectively. This RT difference was not significant [t(14) = 0.25, p = .80], ruling out the possibility that the density of the background lines could account for the RT differences observed in Experiment 1a. Because the background in Experiment 1a reliably induced differences in perceived size, we conclude that the illusory-cue-size effect is indeed driven by differences in the perceived size or depth of the attended object, and that attentional focusing is driven by high-level object representations.

Experiment 2a

The illusion-inducing background used in Experiment 1a was a simple line drawing. In Experiment 1a, we tested whether our findings would generalize to a more complex, naturalistic scene that also conveyed depth. To this end, we replaced the simple line backgrounds of Experiment 1 with a photograph of an airport corridor that also induced the Ponzo illusion.Footnote 3

Method

Observers

Fourteen undergraduate students (three males, 11 females, all right-handed; ages 19–22 years) at Johns Hopkins University participated for course credit. All reported normal or corrected-to-normal vision and were naïve as to the purpose of the experiment.

Apparatus and stimuli

The details of the apparatus and stimulus presentation were identical to those in Experiment 1a, except as follows. The entire screen was filled with a digital color photograph of an airport corridor (see Fig. 2). A red fixation square (0.2° × 0.2°) with a 1-pixel dark-red outline was superimposed on the image.

Illustration of the stimuli in Experiment 2a. Column A illustrates the stimuli when the fixation stimulus was on the left; column B illustrates the stimuli with the fixation stimulus on the right. The top panels illustrate perceptually smaller cues, and the bottom panels illustrate perceptually larger cues. The photograph depicts O’Hare International Airport, United Airlines Terminal, reprinted with permission. Copyright Ingram Publishing by Thinkstock

The illusion-inducing photograph has a vanishing point located at the horizontal meridian of the photograph and 1.3° below the vertical meridian. This central vanishing point allowed us to use both the left and right sides of the image to test whether the illusory-cue-size effect would be robust to the various differences in the left and right sides of the photograph (e.g., differences in brightness, in density of information, etc.). On each trial, a rectangle (2° × 0.6°) was presented at one of three locations: at the center of the photograph near the vanishing point (causing the rectangle to be perceptually larger; see Fig. 2, lower panels), or 5° to the lower left or lower right of the center (causing the rectangle to be perceptually smaller; see Fig. 2, upper panels). On half of the trials, the fixation square was presented halfway between the locations of the left rectangle and the central rectangle (left fixation), whereas on the other half of the trials, the fixation square was presented halfway between the locations of the right rectangle and the central rectangle (right fixation). The rectangle on any particular trial always appeared in one of the two locations adjacent to the fixation square. As in Experiment 1, the target appeared randomly in either the top quarter or the bottom quarter of the cue. It should be noted that the vertical locations of the rectangles and fixation squares were necessarily aligned to the vanishing point, not to the exact vertical meridian of the photograph.

Procedure

The procedure matched that of Experiment 1a, except that each trial began with the appearance of either the left or right fixation. On a random 50 % of the trials, the perceptually smaller rectangle then appeared; on the remaining trials, the perceptually larger rectangle appeared. Each participant completed 480 trials.

Results and discussion

The data were analyzed in a 2 (perceived rectangle size: large, small) × 2 (fixation side: left, right) × 2 (target location: top, bottom) repeated measures ANOVA. Replicating the illusory-cue-size effect observed in Experiment 1a, we found that participants were reliably faster to detect the target when the rectangle was perceptually smaller than when it was perceptually larger [F(1, 13) = 11.77, p = .004, η 2 = .48]. See Fig. 3.

Mean reaction times (± SEMs) in Experiment 2a as a function of perceived cue size and fixation side

The main effect of fixation side was not significant [F(1, 13) < 1]. However, mean RTs were faster when the target appeared in the bottom rather than the top quarter of the rectangle [F(1, 13) = 9.02, p = .01, η 2 = .41]. Of note, however, this effect did not vary reliably as a function of perceived rectangle size [F(1, 13) < 1] or of fixation side [F(1, 13) = 2.239, p = .16].

The interaction between fixation side and perceived rectangle size was not reliable [F(1, 13) < 1], and the difference in RTs to targets appearing in perceptually smaller versus perceptually larger rectangles was reliable for both left and right fixations [left: t(13) = 3.09, p = .009; right: t(13) = 2.84, p = .014]. The replication of the illusory-cue-size effect both within and across experiments emphasizes that the modulation of attentional focusing by perceptual size is robust to differences in the details of the inducing background. The three-way interaction between perceived rectangle size, fixation side, and target location was not reliable [F(1, 13) = 1.574, p = .232].

Experiment 2b

It is known that attentional resolution is greater in the lower visual field (He, Cavanagh, & Intrilligator, 1996, 1997) and that attention increases apparent contrast more in the lower vertical meridian than in the upper vertical meridian (Fuller, Rodriguez, & Carrasco, 2008). If RTs are faster to targets lower in the scene simply due to an enhancement of attentional resolution or of apparent contrast between the target and the rectangle, this could provide an alternative account of the results of Experiment 2a, because the perceptually smaller rectangle always appeared lower in the photograph than the perceptually larger rectangle. We tested this account by removing the illusion-inducing background, leaving only the fixation stimulus, rectangles, and targets. Any effect of the vertical location of the rectangle should remain, whereas any effect of the perceived sizes of the rectangles should be eliminated when the depth cues were omitted.

Method

Observers

Fifteen undergraduates (four male, 11 female, 14 right-handed, one left-handed; ages 19–25 years) at Johns Hopkins University participated for course credit. All participants reported normal or corrected-to-normal vision and were naïve as to the purpose of the experiment.

Stimuli and procedure

The apparatus and stimulus presentation details were identical to those of Experiment 2a, except for the removal of the illusion-inducing background.

Results and discussion

The mean RTs were strikingly similar in all experimental conditions: 340 (SD = 48.3) and 346 ms (SD = 51.1) for the upper and lower rectangles, respectively, when fixation was on the right; 344 (SD = 53) and 346 ms (SD = 59.5) for the upper and lower rectangles, respectively, when fixation was on the left.

The data were analyzed in a 2 (fixation side: left, right) × 2 (rectangle location: upper, lower) × 2 (target location: top, bottom) repeated measures ANOVA. Critically, the main effect of rectangle location (F < 1) was not reliable, nor were there any other reliable effects (all Fs < 1). Thus, removing the background eliminated the illusory-cue-size effect. Furthermore, because no effect of vertical location emerged, these results rule out the possibility that differences in attentional resolution or perceived contrast between the upper and lower hemifields could account for the illusory-cue-size effect observed in Experiment 2a.

General discussion

Over the past several decades, much progress has been made in understanding the orienting of visual attention (e.g., Carrasco, 2011; Cave & Wolfe, 1990; Folk, Remington, & Johnston, 1992; LaBerge, 1995; Wolfe, 1994, 2007). Considerably less is known, however, about an independent component of attentional control—attentional focusing. Although changes to the spatial extent of focal attention affect many aspects of visual cognition—from the speed and accuracy of target detection, to stimulus discrimination, to perceived contrast, to the temporal sensitivity of the visual system (Barriopedro & Botella, 1998; Castiello & Umiltà, 1990; Egeth, 1977; Eriksen & St. James, 1986; Eriksen & Yeh, 1985; Hermann, Montaser-Kouhasari, Carrasco, & Heeger, 2010; Jefferies, Enns, & Di Lollo, 2013; Jefferies et al., 2007; Maringelli & Umiltà, 1998; M. M. Müller et al., 2003; Turatto et al., 2000)—relatively little is known about the factors that modulate attentional focusing, including the level of object representation used to determine the breadth of attention. There is compelling evidence that the orienting of attention is driven more by high-level object representations than by low-level visual features (e.g., Enns & Rensink, 1990, 1991; He & Nakayama, 1992; Rensink & Cavanagh, 2004; Robertson & Kim, 1999; Suzuki & Cavanagh, 1995; Wang et al., 1994; see also Hochstein & Ahissar, 2002). It is unclear, however, whether high-level representations also drive the expansion and contraction of focal attention. Here we explicitly tested whether attentional focusing is driven by high-level or low-level object representations.

Objects were superimposed on a background inducing a perceptual size illusion in order to manipulate the object’s perceived size while holding its physical size constant. The results revealed that observers respond to perceptually larger objects more slowly than to perceptually smaller objects, even when those objects are physically identical in size. This pattern of results suggests that the breadth of attention, like the orienting of attention, is influenced by high-level object representations, and that when attention is dispersed over a perceptually larger area, target detection is slowed.

Two accounts of the present findings can be considered. The first is that the focus of attention expands or contracts to match the perceived size of an object, with a corresponding change in the speed or effectiveness with which objects (i.e., targets) can be detected, depending on the size of the attended region. This account is consistent with functional neuroimaging findings that the spread of activity in early visual cortex reflects an object’s perceived size (Murray, Boyaci, & Kersten, 2006). An alternative account is that the breadth of attention is not affected by the perceived size of the object, but that observers nevertheless exhibit changes in visual detection efficiency depending on an object’s perceived size. Such a mechanism would enable observers to detect the potentially weaker signals or to resolve the finer details typical of smaller objects. This second account seems rather less likely than the first, however, given evidence that the threshold for detecting small differences in the orientation of a line is actually lower in objects that are physically or perceptually larger (Banks, Geisler, & Bennett, 1987; Campbell & Gubisch, 1966; Schindel & Arnold, 2010). This second account of our findings would then predict that the threshold should instead be lower in smaller objects.

Our results also extend recent findings showing that the perceived distance between stimuli is exaggerated when they appear within the area bounded by an object (Vickery & Chun, 2010), suggesting a perceptual warping of space within attended objects. The perceptual warping of within-object space could arise from changes in the breadth of attention and/or from changes to the efficiency or spatial resolution of processing within the attended region.

Finally, our study dovetails with that of Robertson and Kim (1999), who found that illusory differences in line length reliably modulate within-object RT benefits in a spatial-cueing paradigm. They were among the first to show that perceived space modulates the shifting of visual attention. As we discussed earlier, however, there is strong evidence that the orienting of attention and the focusing of attention are distinct processes. The present findings demonstrate that the breadth of attention is determined by the perceived size—not the retinal image size—of the attended object. This finding, in turn, suggests that the focusing of attention, like the orienting of attention, depends heavily on higher-level object representations that are subject to contextual influences.

Notes

To assess the strength of the Ponzo illusion, 15 new participants completed a size-matching task in which they were presented with the illusion-inducing background (facing randomly left or right), one spatial cue that was fixed in size (the standard), and one spatial cue that was 60 % smaller or 60 % larger than the standard (the test). Participants adjusted the size of the test cue in one-pixel increments until it appeared to be equal in length to the standard. Participants completed 24 trials. The number of pixels by which the participants over- or underestimated the size of the test stimulus provided an estimate of the magnitude of the illusion: In the version tested here, the illusion-inducing background caused a difference of approximately 15 % in the perceived sizes of the cues [t(14) = 6.86, p < .001].

The validity of this eye movement monitoring technique was supported by a separate experiment: Two groups of 15 participants were given a task almost identical to that conducted by Castiello and Umiltà (1990). For one group of participants, eye movements were monitored using the approach described here; for the second group, eye movements were monitored using an EyeLink 1000 system sampling at 1000 Hz with an EyeLink CL Illuminator TT-890 camera. The patterns of results obtained, as well as the magnitudes of the cue-size effect, were indistinguishable between the two groups. Furthermore, the percentages of trials on which an eye movement occurred (defined as an abrupt displacement greater than 0.5 deg of visual angle) were comparable in the two groups (1.9 % in the closed-circuit monitoring system; 2.4 % with the EyeLink system.) [t(29) < 1, n.s.].

A separate group of 16 observers completed a size-matching task to assess the strength of the illusion. Observers were presented with two cues (a standard, which was fixed in size, and a test, which was 60 % larger or smaller than the standard) superimposed on the illusion-inducing background. Participants adjusted the size of the test stimulus in 1-pixel steps until it appeared to be equal in length to the standard. The illusion-inducing background caused the perceived sizes of the cues to differ by 9.7 % [t(15) = 2.35, p = .03] when participants fixated the left side of the display, and 8.4 % [t(15) = 4.4, p < .001] on the right side. The difference in the magnitude of the illusion as a function of display side was not significant [t(15) = 0.32, p = .75].

References

Banks, M. S., Geisler, W. S., & Bennett, P. J. (1987). The physical limits of grating visibility. Vision Research, 27, 1915–1924.

Barriopedro, M. I., & Botella, J. (1998). New evidence for the zoom lens model using the RSVP technique. Perception & Psychophysics, 8, 1406–1414.

Benso, F., Turatto, M., Mascetti, G. G., & Umiltà, C. (1998). The time course of attentional focusing. European Journal of Cognitive Psychology, 10, 373–388.

Brainard, D. H. (1997). The psychophysics toolbox. Spatial Vision, 10, 433–436. doi:10.1163/156856897X00357

Campbell, F. W., & Gubisch, R. W. (1966). Optical quality of the human eye. Journal of Physiology, 196, 558–578.

Carrasco, M. (2011). Visual attention: The past 25 years. Vision Research, 51, 1484–1525. doi:10.1016/j.visres.2011.04.012

Castiello, U., & Umiltà, C. (1990). Size of the attentional focus and efficiency of processing. Acta psychologica, 73(3), 195–209.

Cave, K. R., & Wolfe, J. M. (1990). Modeling the role of parallel processing in visual search. Cognitive Psychology, 25, 225–271. doi:10.1016/0010-0285(90)90017-X

Chen, Q., Marshall, J. C., Weidner, R., & Fink, G. R. (2009). Zooming in and zooming out of the attentional focus: An fMRI study. Cerebral Cortex, 19, 805–819.

Egeth, H. (1977). Attention and preattention. In G. H. Bower (Ed.), The psychology of learning and motivation: Advances in research and theory (Vol. 11, pp. 277–320). New York, NY: Academic Press.

Egly, R., Driver, J., & Rafal, R. D. (1994). Shifting visual attention between objects and locations: Evidence from normal and parietal lesion subjects. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 123, 161–177. doi:10.1037/0096-3445.123.2.161

Enns, J. T., & Rensink, R. A. (1990). Sensitivity to three-dimensional orientation in visual search. Psychological Science, 5, 323–326. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.1990.tb00227.x

Enns, J. T., & Rensink, R. A. (1991). Preattentive recovery of three-dimensional orientation from line drawings. Psychological Review, 98, 335–351.

Eriksen, C. W., & St. James, J. D. (1986). Visual attention within and around the field of focal attention: A zoom lens model. Perception & Psychophysics, 42, 225–240. doi:10.3758/BF03211502

Eriksen, C. W., & Yeh, Y.-Y. (1985). Allocation of attention in the visual field. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 11, 583–597. doi:10.1037/0096-1523.11.5.583

Facoetti, A., Lorusso, M. L., Paganoni, P., Cattaneo, C., Galli, R., & Mascetti, G. G. (2003). The time course of attentional focusing in dyslexic and normally reading children. Brain and Cognition, 53, 181–184.

Facoetti, A., Paganoni, P., Turatto, M., Marzola, V., & Mascetti, G. G. (2000). Visual–spatial attention in developmental dyslexia. Cortex, 36, 109–123.

Fernandes, M. A., Koji, S., Dixon, M. J., & Aquino, J. M. (2011). Changing the focus of attention: The interacting effect of valence and arousal. Visual Cognition, 19, 1191–1211.

Folk, C. L., Remington, R. W., & Johnston, J. C. (1992). Involuntary covert orienting is contingent on attentional control settings. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 18, 1030–1044. doi:10.1037/0096-1523.18.4.1030

Friedman, R. S., & Förster, J. (2010). Implicit affective cues and attentional tuning: An integrative review. Psychological Bulletin, 136, 875–893. doi:10.1037/a0020495

Fuller, S., Rodriguez, R. Z., & Carrasco, M. (2008). Apparent contrast differs across the vertical meridian: Visual and attentional factors. Journal of Vision, 8(1), 16, 1–16. doi:10.1167/8.1.16

Galera, C., von Grünau, M., & Panagopoulos, A. (2005). Automatic focusing of attention on object size and shape. Psicológica, 26, 147–160.

Gmeindl, L., Jefferies, L. N., & Yantis, S. (2014). The breadth of attention modulates the effective capacity of visual sensory memory. Manuscript submitted for publication.

Greenwood, P. M., Parasuraman, P., & Haxby, J. V. (1993). Changes in visuospatial attention over the adult lifespan. Neuropsychologia, 31, 471–485.

He, S., Cavanagh, P., & Intriligator, J. (1996). Attentional resolution and the location of visual awareness. Nature, 383, 334–337. doi:10.1038/383334a0

He, S., Cavanagh, P., & Intriligator, J. (1997). Attentional resolution. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 1, 115–121.

He, Z. J., & Nakayama, K. (1992). Surfaces versus features in visual search. Nature, 359, 231–233.

Hermann, K., Montaser-Kouhasari, L., Carrasco, M., & Heeger, D. J. (2010). When size matters: Attention affects performance by contrast or response gain. Nature Neuroscience, 13, 1554–1559.

Hochstein, S., & Ahissar, M. (2002). View from the top: Hierarchies and reverse hierarchies in the visual system. Neuron, 36, 791–804.

Jefferies, L. N., & Di Lollo, V. (2009). Linear changes in the spatial extent of the focus of attention across time. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 35, 1020–1031. doi:10.1037/a0014258

Jefferies, L. N., Enns, J. T., & Di Lollo, V. (2013). The flexible focus: Whether spatial attention is unitary or divided depends on observer goals. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance. Advance online publication. doi:10.1037/a0034734

Jefferies, L. N., Ghorashi, S., Kawahara, J.-I., & Di Lollo, V. (2007). Ignorance is bliss: The role of observer expectation in dynamic spatial tuning of the attentional focus. Perception & Psychophysics, 69, 1162–1174.

Jefferies, L. N., Roggeveen, A. B., Enns, J. T., Bennett, P. J., Sekuler, A. B., & Di Lollo, V. (2013). On the time course of attentional focusing in older adults. Psychological Research. Advance online publication. doi:10.1007/s00426-013-0528-2

Jonides, J. (1981). Voluntary versus automatic control over the mind’s eye’s movement. In J. Long & A. Baddeley (Eds.), Attention and performance IX (pp. 187–203). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Jonides, J., & Yantis, S. (1988). Uniqueness of abrupt visual onset in capturing attention. Perception & Psychophysics, 43, 346–354. doi:10.3758/BF03208805

LaBerge, D. (1983). Spatial extent of attention to letters and words. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 9, 371–379. doi:10.1037/0096-1523.9.3.371

LaBerge, D. (1995). Attentional processing: The brain’s art of mindfulness. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

LaBerge, D., & Brown, V. (1986). Variations in size of the visual field in which targets are presented: An attentional range effect. Perception & Psychophysics, 40, 188–200.

Lincourt, A. E., Folk, C. L., & Hoyer, W. J. (1997). Effects of ageing on voluntary and involuntary shifts of attention. Ageing, Neuropsychology, and Cognition, 4, 290–303.

Maringelli, F., & Umiltà, C. (1998). The control of the attentional focus. European Journal of Cognitive Psychology, 10, 225–246.

Marr, D. (1982). Vision: A computational investigation into the human representation and processing of visual information. San Francisco, CA: W. H. Freeman.

Müller, M. M., Malinowki, P., Gruber, T., & Hillyard, S. A. (2003a). Sustained division of the attentional spotlight. Nature, 424, 309–312. doi:10.1038/nature01812

Müller, N. G., Bartelt, O. A., Donner, T. H., Villringer, A., & Brandt, S. A. (2003b). A physiological correlate of the “Zoom Lens” of visual attention. Journal of Neuroscience, 23, 3561–3565.

Murray, S. O., Boyaci, H., & Kersten, D. (2006). The representation of perceived angular size in human visual cortex. Nature Neuroscience, 9, 429–434.

Nakayama, K., & Mackeben, M. (1989). Sustained and transient components of focal visual attention. Vision Research, 29, 1631–1647.

Ponzo, M. (1910). Intorno ad alcune illusioni nel campo delle sensazioni tattili, sull’illusione di Aristotele e fenomeni analoghi. Archiv für die Gesamte Psychologie, 16, 307–345.

Posner, M. I. (1980). Orienting of attention. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 32, 3–25. doi:10.1080/00335558008248231

Rensink, R. A., & Cavanagh, P. (2004). The influence of cast shadows on visual search. Perception, 33, 1339–1358. doi:10.1068/p5322

Robertson, L. C., & Kim, M.-S. (1999). Effects of perceived space on spatial attention. Psychological Science, 10, 76–79. doi:10.1111/1467-9280.00110

Ronconi, L., Basso, D., Gori, S., & Facoetti, A. (2014). TMS on right frontal eye fields induces an inflexible focus of attention. Cerebral Cortex, 24, 396–402. doi:10.1093/cercor/bhs319

Ronconi, L., Gori, S., Ruffino, M., Molteni, M., & Facoetti, A. (2013). Zoom-out attentional impairment in children with autism spectrum disorder. Cortex, 49, 1025–1033. doi:10.1016/j.cortex.2012.03.005

Rowe, G., Hirsh, J. B., & Anderson, A. K. (2007). Positive affect increases the breadth of attentional selection. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 104, 383–388.

Schindel, R., & Arnold, D. H. (2010). Visual sensitivity can scale with illusory size changes. Current Biology, 20, 841–844.

Scholl, B. J., & Pylyshyn, Z. (1999). Tracking multiple objects through occlusion: Cues to visual objecthood. Cognitive Psychology, 38, 259–290.

Serences, J. T., Schwarzbach, J., Courtney, S. M., Golay, X., & Yantis, S. (2004). Control of object- based attention in human visual cortex. Cerebral Cortex, 14, 1346–1357.

Suzuki, S., & Cavanagh, P. (1995). Facial organization blocks access to low-level features: An object inferiority effect. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 21, 901–913. doi:10.1037/0096-1523.21.4.901

Theeuwes, J. (1992). Perceptual selectivity for color and form. Perception & Psychophysics, 51, 599–606. doi:10.3758/BF03211656

Tipper, S. P., Driver, J., & Weaver, B. (1991). Object-centered inhibition of return of visual attention. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 43A, 289–298. doi:10.1080/14640749108400971

Turatto, M., Benso, F., Facoetti, A., Galfano, G., Mascetti, G. G., & Umiltà, C. (2000). Automatic and voluntary focusing of attention. Perception & Psychophysics, 62, 935–952. doi:10.3758/BF03212079

Turatto, M., Benso, F., & Umiltà, C. (1999). Focusing of attention in professional women skiers. International Journal of Sport Psychology, 30, 339–349.

Vickery, T. J., & Chun, M. M. (2010). Object-based warping an illusory distortion of space within objects. Psychological Science, 21, 1759–1764.

Wang, Q., Cavanagh, P., & Green, M. (1994). Familiarity and pop-out in visual search. Perception & Psychophysics, 56, 495–500. doi:10.3758/BF03206946

Weichselgartner, E., & Sperling, G. (1987). Dynamics of automatic and controlled visual attention. Science, 238, 778–780. doi:10.1126/science.3672124

Wolfe, J. M. (1994). Guided Search 2.0: A revised model of visual search. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 2, 202–238. doi:10.3758/BF03200774

Wolfe, J. M. (2007). Guided Search 4.0: Current progress with a model of visual search. In W. D. Gray (Ed.), Integrated models of cognitive systems (pp. 99–119). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Yantis, S., & Jonides, J. (1984). Abrupt visual onsets and selective attention: Evidence from visual search. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 10, 601–621. doi:10.1037/0096-1523.10.5.601

Author note

Support for this research was provided by a Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada postdoctoral fellowship to L.N.J., an NIA postdoctoral National Research Service Award (No. T32-AG027668) to L.G., and NIH Grant No. RO1-DA13165 to S.Y. We thank Emma Wampler for help with the data collection.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jefferies, L.N., Gmeindl, L. & Yantis, S. Attending to illusory differences in object size. Atten Percept Psychophys 76, 1393–1402 (2014). https://doi.org/10.3758/s13414-014-0666-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.3758/s13414-014-0666-7