Abstract

The visuospatial negative priming effect—that is, the slowed-down responding to a previously ignored location—is partly due to response inhibition associated with the previously ignored location (Buckolz, Goldfarb, & Khan, Perception & Psychophysics 66:837-845 2004). We tested whether response inhibition underlies spatial negative priming in the auditory modality as well. Eighty participants localized a target sound while ignoring a simultaneous distractor sound at another location. Eight possible sound locations were arranged in a semicircle around the participant. Pairs of adjacent locations were associated with the same response. On ignored repetition trials, the probe target sound was played from the same location as the previously ignored prime sound. On response control trials, prime distractor and probe target were played from different locations but were associated with the same response. On control trials, prime distractor and probe target shared neither location nor response. A response inhibition account predicts slowed-down responding when the response associated with the prime distractor has to be executed in the probe. There was no evidence of response inhibition in audition. Instead, the negative priming effect depended on whether the sound at the repeatedly occupied location changed identity between prime and probe. The latter result replicates earlier findings and supports the feature mismatching hypothesis, while the former is compatible with the assumption that response inhibition is irrelevant in auditory spatial attention.

Similar content being viewed by others

Responding to the identity of a stimulus that was ignored in a previous presentation is overall slowed down—and often more error prone—than responding to a stimulus that was not part of a previous presentation. This phenomenon, termed the identity negative priming effect, is widely used to study mechanisms of selective attention and memory that allow goal-directed behavior in multistimulus environments (for reviews, see Fox, 1995; Mayr & Buchner, 2007; Tipper, 2001). Identity negative priming is typically investigated by simultaneously presenting target and distractor stimuli that have to be distinguished on the basis of a feature such as color. A response is based on the identity of the stimulus.

In the spatial variant of the negative priming task, participants are required to locate a predefined target in the presence of a distractor. On ignored repetition trials, the probe target is presented at the spatial location of the previous prime distractor. On control trials, there is no repetition of stimulus locations between successive prime–probe trials. Typically, ignored repetition trials result in prolonged response times, as compared with control trials, constituting the spatial negative priming effect (Chao, 2009; Milliken, Tipper, & Weaver, 1994; Tipper, Brehaut, & Driver, 1990), while accuracy is not necessarily impaired (Christie & Klein, 2008; Fitzgeorge & Buckolz, 2008; Guy, Buckolz, & Pratt, 2004). The spatial negative priming paradigm serves as a useful instrument for identifying how the cognitive system deals with objects appearing at to-be-ignored locations while attention is focused on task-relevant information at other positions in space. The explanations of the spatial negative priming effect resemble those accounts that have been put forward to explain identity-based negative priming: The inhibition account posits that the spatial representation of distractors is selectively inhibited (Milliken, Tipper, Houghton, & Lupiáñez, 2000; Tipper et al., 1990). Alternatively, the episodic retrieval account posits that the retrieval of prime episodes is triggered by presenting a probe target at the location of the prime distractor (Neill & Valdes, 1992; Neill, Valdes, Terry, & Gorfein, 1992), which serves as a retrieval cue to the prime episode. Retrieved prime episodes contain the information that no response was executed to objects at the distractor location.

Recently, a study by Buckolz, Goldfarb, and Khan (2004) expanded the discussion about the processes underlying the selection of target stimuli in the presence of simultaneous distractors by proposing a motor-related cause of the spatial negative priming effect. The authors argued that, in a typical spatial negative priming task, each location is mapped onto a discrete response. On ignored repetition trials, a response has to be executed that was assigned to the distractor in the previous trial. It was proposed that negative priming is not the aftereffect of previously ignoring a stimulus location but stems from the requirement to execute a previously suppressed motor response on ignored repetition trials. According to Buckolz et al. (2004), simultaneously presenting target and distractor stimuli in the prime leads to an automatic activation of both their assigned responses. This initial activation is thought to be followed by the inhibition of the distractor-assigned motor response in order to counteract a response conflict in favor of the required target response. It is important to note that spatial negative priming has been repeatedly observed for trials without a prime target, implying no overt prime response (e.g., Buckolz, Avramidis, & Fitzgeorge, 2008; Milliken et al., 2000). In this case, a conflict is thought to arise in the prime between the activation of the distractor-assigned response and the need to withhold this specific response, rather than between the activated target and distractor responses. In both cases—that is, in situations with and in situations without a prime target and a prime response requirement—the residual inhibition of the former distractor response prolongs its execution as the correct probe response on ignored repetition trials. In the following, the term conflict is used for all situations in which an activated response is not in accord with the correct response requirement. This response-based explanation is corroborated by electrophysiological and behavioral evidence of automatic response activation and subsequent inhibition of distractor-related motor responses in similar experimental paradigms such as the well-known flanker and Simon tasks (Buckolz, O'Donnell, & McAuliffe, 1996; Coles, Gratton, Bashore, Eriksen, & Donchin, 1985; De Jong, Liang, & Lauber, 1994; Eriksen, Coles, Morris, & O'Hara, 1985; Ridderinkhof, 2002; Smid, Mulder, & Mulder, 1990; Valle-Inclán & Redondo, 1998), as well as the negative compatibility task where the to-be-executed response was recently activated by a masked prime and, thus, had to be inhibited (Eimer, 1999; Eimer, Schubö, & Schlaghecken, 2002).

To test the response inhibition account of spatial negative priming, Buckolz et al. (2004; for replications, see Fitzgeorge, Buckolz, & Khan, 2011; Guy & Buckolz, 2007; Guy, Buckolz, & Khan, 2006) isolated the influence of reexecuting a previously irrelevant response in a spatial negative priming task by modifying the location–response assignment. Participants had to locate a dark blue rectangle by manually pressing a location-assigned response key while ignoring a light blue distractor rectangle. The two stimuli were presented in two out of five horizontally aligned display locations. The two left and the two right locations were each mapped onto distinct spatially compatible response keys. When a target stimulus appeared at the center location, participants were free to choose one of the two keys that were assigned to the two adjacent locations. With this assignment, reexecuting a prime distractor response in the probe could take place without presenting the probe target at the former prime distractor location: Presenting a prime distractor stimulus at the center location was assumed to result in an automatic activation and subsequent inhibition of both responses associated with the center location, making these responses less available in the following probe.Footnote 1 Execution of the inhibited responses could be probed by presenting the probe target at one of the two adjacent locations (assigned to the same response). This resulted in so-called response control trials, in which the withheld prime response had to be executed in the probe trial without location repetition between the prime and probe presentations. Response times were compared among response control trials, traditional ignored repetition trials in which a response repetition was always accompanied by a location repetition, and control trials without location and response repetition between prime and probe. The results showed that responses on response control and ignored repetition trials were slowed down, in comparison with control trials. This pattern of results suggests a response locus of spatial negative priming because response repetition, rather than location repetition, was crucial for finding a slowdown in responding. As an additional finding, reaction times were significantly longer on response control trials than in ignored repetition trials. Following Buckolz et al.’s (2004) argumentation, the latter result indicates that prime distractor-to-probe target location repetitions actually facilitate stimulus processing. Overall, Buckolz et al.’s (2004) findings suggest that response-based inhibition can be the sole cause of the spatial negative priming effect, which stands in contrast to the widespread assumption of location-based inhibition as the underlying mechanism.Footnote 2

Until recently, investigations of the spatial negative priming effect were restricted to the visual modality, although the auditory system is frequently concerned with focusing on sounds from a distinct location in space in the presence of interfering sounds from different directions. There are numerous differences between audition and vision in basic stimulus processing, perceptual organization, and the availability of peripheral information to aid selection (Banks, Roberts, & Ciranni, 1995). Therefore, employing the spatial negative priming paradigm permits further insight into the particular mechanisms underlying spatial selective attention in audition. Only two recent studies have examined spatial negative priming in audition. In the study of Mayr, Hauke, and Buchner (2009), participants had to locate one of two simultaneous sounds (piano, crow), originating from two (out of four) different and easily discriminable loudspeaker positions. The identity of the target sound was indicated by a visual cue preceding the auditory presentation. On ignored repetition trials, the probe target sound was presented from the loudspeaker from which the prime distractor had just been presented. On control trials, there was no location repetition between successive presentations. In addition, the sound identity of prime distractor and probe target was manipulated. On ignored repetition match trials, prime distractor and probe target were identical sounds. On ignored repetition mismatch trials, prime distractor and probe target were different sounds. Responses to sounds at previously ignored locations were not generally slowed down. Instead, the negative priming effect was modulated by the match/mismatch manipulation: Prolonged response times were found only on ignored repetition trials with a sound mismatch at the repeated location, whereas response times on match trials did not differ from the response times in the control condition. This result cannot be explained completely by inhibition of ignored locations during the prime or by retrieval of probe-incompatible prime episode information associated with the ignored location. Instead, it supports the so-called feature mismatching hypothesis of spatial negative priming (see Mayr, Buchner, Möller, & Hauke, 2011, for a replication).

The feature mismatching hypothesis was originally put forward by Park and Kanwisher (1994) to explain the visuospatial negative priming effect. In essence, slowed-down responses to previously ignored locations are assumed to derive from changing features at repeated locations between the prime and probe presentations. According to the feature mismatching hypothesis, stimulus identities and their spatial locations are bound into object files (Kahneman, Treisman, & Gibbs, 1992), irrespective of their status as target or distractor on the current trial. Identical repetitions of a stimulus are assumed to yield reduced response times and error rates, whereas stimulus changes between prime and probe are associated with a cost in latency and accuracy. Park and Kanwisher argued that on ignored repetition trials, feature mismatches occur by default. This is so because target and distractor identities usually remain constant across trials. If, for example, participants respond to the location of a target stimulus (e.g., “@”) while ignoring a distractor stimulus (e.g., “+”) at a different location in the prime, the probe target stimulus “@” appears at the location of the prime distractor “+” to establish an ignored repetition trial. The location repetition is therefore inevitably accompanied by a feature mismatch, rendering the feature mismatching hypothesis a valid alternative explanation of visuospatial negative priming. Park and Kanwisher (Experiment 4) demonstrated the absence of a negative priming effect for trials without a feature mismatch by reversing target and distractor identities from prime to probe (while participants were required to localize a symbol “X” and ignore a symbol “O” during the prime, they had to localize the “O” and to ignore the “X” in the subsequent probe presentation, resulting in ignored repetition trials without a feature mismatch). Although the contribution of feature mismatching on visuospatial negative priming was initially demonstrated by Park and Kanwisher, the majority of later studies demonstrated a visuospatial negative priming effect in the absence of feature mismatches. This led to the conclusion that the feature mismatching hypothesis can be excluded as the main explanation of negative priming in vision (Milliken et al., 2000; Milliken et al., 1994; Tipper, Weaver, & Milliken, 1995).

In audition, in contrast, feature mismatching can explain why reactions to previously ignored locations are slowed down (Mayr et al., 2011; Mayr et al., 2009). However, it is not clear whether response inhibition also contributes to this slowdown. This is so because, just as in visual spatial negative priming tasks, repetitions of the ignored prime location as the probe target location also involves a repetition of the response. The aim of the present study thus was to test whether distractor-related response inhibition contributes to spatial negative priming in audition. To this end, the present study was designed to isolate the influence of reexecuting a response that had been assigned to the previous prime distractor from the influence of responding to a sound at a previously ignored location. In analogy to Buckolz et al. (2004), we used a many-to-one location–response mapping with eight possible sound locations, of which pairs of two were assigned the same response. This 8:4 location–response mapping made it possible to generate (1) trials with location and response repetitions between prime distractor and probe target (ignored repetition trials), (2) trials with response repetitions but no location repetitions between prime distractor and probe target (response control trials), and (3) trials devoid of any response or location repetitions (control trials).

Hypothesis testing was based on two crucial trial type comparisons: the comparison between response control and control trials, as well as the comparison between ignored repetition and response control trials. If automatic response activation followed by response inhibition takes place for auditory distractors, responding on response control trials should be impaired, as compared with control trials. The standard negative priming effect (i.e., the comparison between ignored repetition and control trials) was also calculated and tested, but note that this effect is equivocal with respect to the underlying mechanism(s) because it confounds response and location repetition effects. Given that preceding studies of auditory spatial negative priming (Mayr et al., 2011; Mayr et al., 2009) supported a feature mismatching explanation, the predictions of the response inhibition account were directly pitted against the feature mismatching account. This was done by including sound repetition (repeated vs. changed) between prime distractor and probe target as an additional experimental variable. It was thus possible to compare performance in ignored repetition trials with and without a feature mismatch. The feature mismatching hypothesis predicts that responding on ignored repetition trials will be slowed down, as compared with their respective control trials, only in the case of a sound change at the repeated location. In contrast, response times on ignored repetition trials containing sound repetitions should be equal to, or even shorter than, response times on the respective control trials. Following the feature mismatching account, both types of response control trials (i.e., sound-repeated and sound-changed trials) should yield response times comparable to those on their respective control trials, since there is no location repetition and, hence, no feature (mis)match on response control trials.

Method

Participants

Five out of 85 participants did not reach the learning criterion in either the first or the second training phase (see below), resulting in a total sample of 80 adults (51 females) ranging in age from 19 to 40 years (M = 24). Participants were tested individually and either were paid or received course credit.

Materials

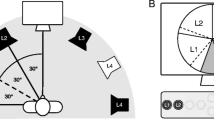

Four easily discriminable instrumental sounds (guitar, drum, triangle, harmonica) were digitally recorded at a rate of 48 kHz, subsequently cut to a length of 400 ms (10-ms linear onset–offset ramps), and normalized to have identical RMS energy. All sounds were presented at an intensity of approximately 64 dB(A) SPL. Participants sat in the middle of a 2.5 × 3.5 m room with their head placed on a chinrest, facing a 16-in. computer screen. Eight loudspeakers (JBL control 1 Pro) were placed in a semicircular arrangement around the participant with an angular disparity of 25.7° between speakers and a distance of 93 cm from the participant (Fig. 1). The semicircular arrangement was preferred to a circular arrangement to avoid the increased difficulty of front–back discriminations. The heights of the loudspeakers varied as documented in Fig. 1’s caption to enhance discriminability. Each trial consisted of a prime and a probe display. Each display began with the presentation of a picture depicting the target instrument, followed by two simultaneously presented sounds from different locations. Participants were instructed to locate the target sound by manually pressing one of four horizontally aligned keys on a response box while ignoring the distractor sound. For the ease of reference, speaker positions in Fig. 1 are labeled as L1–L8 from left to right; the keys of the response box are labeled accordingly with A–D. Pairs of speakers were mapped onto one response key. The assignment of the speaker pairs to the response keys was kept spatially compatible; that is, responses to the speaker pairs L1–L2, L3–L4, L5–L6, and L7–L8 required presses of the keys A, B, C, and D, respectively. Participants used their right and left middle and index fingers to operate the response keys.

Loudspeaker arrangement (labeled L1 to L8). Two loudspeakers were associated with the same response key (L1–L2 with key A, L3–L4 with key B, L5–L6 with key C, and L7–L8 with key D). Speaker heights were 102 cm for L3 and L8, 111 cm for L1 and L6, 129 cm for L4 and L7, and 138 cm for speakers L2 and L5

Trials belonged to either the ignored repetition subdesign or the attended repetition subdesign. In the ignored repetition subdesign, feature repetitions between the prime distractor and the probe target were systematically manipulated, whereas in the attended repetition subdesign, feature repetitions between the prime target and probe target were varied. The ignored repetition subdesign was of primary theoretical interest. The attended repetition subdesign was primarily included to avoid predictability of the probe response based on prime responding, but the results obtained in this subdesign were also informative with respect to the general mechanisms underlying auditory selection.

First, trials in the ignored repetition subdesign were constructed by generating a set of so-called basic prime–probe trials. Basic trials did not include any response or location repetitions between the four stimuli on the trial. This implies that all four prime and probe stimuli of a basic trial had to be associated with different response categories. Given four possible response categories (i.e., the response keys A–D), there were 24 prime–probe response combinations, resulting in 24 basic trials. Because two speaker locations were mapped onto the same response key, actual stimulus locations for each of the 24 basic trials were determined by randomly selecting one of the two locations for each response category. All other trial types of the ignored repetition subdesign were constructed from this set of basic trials. Ignored repetition trials were created by presenting the prime distractor on each basic trial at the location of the probe target. For response control trials, the prime distractor was presented at the location that was adjacent to the probe target location and associated with the same response. Finally, a control trial was created by presenting the prime distractor at the location that was adjacent to the probe target location but was linked to a different response key. Note that the basic trials and the control trials were similar in that they both lacked location and response repetitions. The crucial difference between these two trial types is that for all control trials, but not for the basic trials, the probe target was presented at the location adjacent to the prime distractor. In this respect, control trials were parallel to response control trials, both of them having the same physical distance between prime distractor and probe target location, differing only with regard to the prime distractor-to-probe target response repetition. As an exception, response control and control trials did not exhibit the same physical distance (25.7°) between prime distractor and probe target location when the probe target was presented at L1 or L8. For probe targets presented at L1, the prime distractor of the appropriate response control trial was presented at L2, whereas it was presented at L8 on the respective control trial. Given the semicircular (instead of a full circular) arrangement of the loudspeakers, this implied a larger location distance in the latter trial type, which might influence responding. As a consequence, all quadruples (basic, control, response control, ignored repetition) with the probe target at L1 or L8 were excluded from the statistical analysis.

In the process of constructing quadruples of parallel trials (basic, control, response control, ignored repetition), invalid control trials were occasionally generated (e.g., trials that contained response repetitions between prime distractor and probe distractor). In these cases, the whole quadruple of trials was discarded and generated anew. The algorithm was repeated until 96 unique trials (24 of each trial type) were generated.

Next, sound identity information was added to the trials. Each of the 96 trials was once implemented without any sound identity repetition between prime and probe presentation and once with a sound identity repetition between prime distractor and probe target. The former trials require the presentation of four different stimulus identities as target and distractor sounds. In each case, sound identities were selected individually for each trial. Adding sound identity to the four trial types resulted in a total of eight different trial types in the ignored repetition design. In fact, basic trials were presented in the experiment but not included in the analysis, given that there were designated control trials with preferable properties. Figure 2 provides examples of the six theoretically most relevant trial types in the ignored repetition design.

Illustrative examples of the three crucial prime–probe trial types (control, response control, ignored repetition) in the ignored repetition subdesign. The upper panel illustrates trials with a prime distractor to probe target sound repetition; the lower panel shows trials with a prime distractor to probe target sound change. The key layout and the correct prime and probe responses for the examples are displayed for both panels. The target sound was visually cued on the monitor in front of the participant. To simplify matters, the visual cue is depicted as a written word, and not in picture format (here,“drum” in the prime, “triangle” in the probe)

The same algorithm as that described above was applied to construct trials in the attended repetition subdesign, except that all repetitions (location, response, identity) referred to the targets in prime and probe, resulting in 192 trials in this subdesign. Overall, the experimental set containing 384 trials was presented in random order.

Procedure

Two training phases were administered to ensure that participants were able to discriminate between locations (training 1) and to familiarize them with the assignment of locations to response keys (training 2). Throughout the training, the target sound was indicated by a picture of the to-be-heard instrument on the computer screen. In training 1, participants saw a schematic image of the semicircular speaker arrangement on the screen. The task was to locate a target sound in the presence of a simultaneous distractor by performing a mouse click on the appropriate speaker in the image. Targets comprised all possible combinations of sounds and locations. Distractors were randomly chosen, with the restriction that they matched neither the location nor the sound identity of the target. Training 2 began after 75 % of the past 15 trials had received correct responses. In training 2, participants had to localize target sounds in the presence of distractors by pressing the respective keys of the response box as in the experiment proper. Randomly drawn prime trials of the experimental set were presented as stimuli. Participants proceeded to the experimental trials after at least 75 % of the past 15 trials had received correct responses.

Experimental trials began with the presentation of a cue depicting the to-be-attended instrument. The prime sounds were presented 500 ms after the onset of the visual cue. The picture remained visible until a response was made or an interval of 3,000 ms was exceeded. After the response, a 1,000-ms prime–probe interval elapsed before the onset of the visual probe cue, followed by the probe sounds after another 500 ms. All responses faster than 100 ms and slower than 3,000 ms were counted as invalid. Audio-visual feedback of the correctness of both responses was displayed for 1,000 ms after the probe response had been executed. A 1,000-ms intertrial interval preceded the next trial. After every 12th trial, participants received feedback summarizing their response speed and accuracy in the current block. They initiated the next block at their own discretion. The experiment lasted about 74 min.

Design

The experiment comprised two subdesigns (ignored repetition, attended repetition), but the ignored repetition subdesign was of primary interest. The 3 × 2 ignored repetition subdesign comprised a repeated measures design with trial type (control, response control, ignored repetition) and sound repetition (repeated vs. changed) as within-subjects variables. The primary dependent variable was participants’ average reaction time, but error rates were also analyzed.

Hypothesis testing was based on the two planned contrasts (1) between response control and control trials and (2) between ignored repetition and response control trials. The former comparison tested the sole impact of executing the prior distractor response, while the latter isolated the effect of responding to a location that was occupied by the distractor in the previous presentation. In addition, ignored repetition trials were compared with control trials to assess the standard spatial negative priming effect. However, the result of this comparison is not diagnostic with respect to the underlying mechanisms and is, therefore, not treated as theoretically relevant. An a priori power analysis (Faul, Erdfelder, Lang, & Buchner, 2007) showed that given α = β = .05, a sample size of N = 70 was necessary to detect effects of size d z = 0.40 (medium to small effects in terms of Cohen, 1988) between response control and control trials, as well as between ignored repetition and response control trials. We were able to collect data from N = 80 participants, so that the power was somewhat larger than what we had planned for (1 − β = .97). The global level of alpha was maintained at .05. The Bonferroni–Holm method (Holm, 1979) was applied to prevent α-error accumulation for the two planned contrasts. All reported t-tests for the planned contrasts were one-tailed, while comparisons that were not directly related to the hypotheses were based on two-tailed t-tests. Because no directed hypotheses were formulated for the attended repetition subdesign, all reported t-tests for this subdesign are two-tailed.

Results

Response accuracy for both training phases was high, with 81 % (SD = 1.06) and 89 % (SD = 1.91) mean correct responses for the last 15 trials in training 1 and 2, respectively. One-sample t-tests confirmed that performance was above chance (i.e., above 12.5 % and 25 % correct responses for training 1 and 2, respectively), with t(79) = 87.49, p < .001, d z = 9.78 for training 1 and t(79) = 71.43, p < .001, d z = 7.99 for training 2. Thus, participants were able to discriminate between adjacent locations well, and they also mastered the location–response mapping of the experimental task proper.

Attended repetition trials were primarily employed to obscure global contingencies between prime and probe presentations but were also included in the statistical analysis because they are also informative with respect to the general mechanisms underlying auditory selection. Results for both subdesigns are shown in Table 1. Only probe responses following correct prime responses were used to evaluate response speed and accuracy. Separate analyses were conducted for sound-repeated and sound-changed trials to separate effects of location–identity mismatch. Following the Bonferroni–Holm rationale (Holm, 1979), p-values for the (in the present case, two) hypothesis-relevant comparisons were arranged in ascending order, starting with the smallest value. Dividing the global alpha level of .05 by the number of comparisons adjusted the critical alpha level for the decision about the smallest p-value to .025, while the critical alpha level for the second comparison remained at .05. For convenience, the critical alpha levels are now reported in brackets after the exact empirical p-values. The statistical analysis is reported for the ignored repetition subdesign, followed by the attended repetition subdesign.

For sound-changed trials, presenting the probe target stimulus at the former location of the prime distractor on the ignored repetition trials prolonged response times, relative to control trials, t(79) = 2.61, p = .012, d z = 0.29. The standard spatial negative priming effect was thus present in the data. However, it could have been caused by response or location inhibition, as well as feature mismatching. Executing the response that had been successfully withheld in the preceding prime (i.e., response control trials) was not significantly slowed down, as compared with control trial responses, t(79) = 0.61, p = .272 [α = .050], d z = 0.07. Furthermore, responses were slower on ignored repetition than on response control trials, t(79) = 2.04, p = .023 [α = .025], d z = 0.23.

Among sound-repeated trials, there was a descriptive trend showing faster responses on ignored repetition than on control trials, t(79) = −1.66, p = .102, d z = 0.19. Again, disentangling the causal mechanisms for this result demanded two comparisons. Examination of response control trials revealed no statistically significant effect of executing the prior distractor response, relative to control trials, t(79) = 0.82, p = .207 [α = .050], d z = 0.09. Response speed was significantly faster on ignored repetition than on response control trials, t(79) = −2.17, p = .017 [α = .025], d z = 0.24.

Mean reaction times (upper panel) and error rates (lower panel) as a function of trial type (control, response control, ignored repetition) and sound repetition (repeated vs. changed) for the ignored repetition subdesign. The error bars depict the standard errors of the means. Note that the standard errors cannot be used to estimate any differences between the displayed conditions

The analysis of error rates did not compromise the response time results, because no statistically significant differences were obtained in any of the relevant comparisons. Specifically, for sound-changed trials, ignored repetition and response control trials did not differ from control trials, with t(79) = 0.47, p = .320, d z = 0.05, and t(79) = 0.99, p = .161 [α = .025], d z = 0.11, respectively. Error rates on ignored repetition trials were comparable to those on response control trials, t(79) = −0.45, p = .327 [α = .050], d z = 0.05. With sound-repeated trials, error rates differed neither between ignored repetition and control trials, t(79) = 0.55, p = .293, d z = 0.06, nor between response control and control trials, t(79) = −0.60, p = .275 [α = .050], d z = 0.07. Finally, no difference was obtained between ignored repetition and response control trials, t(79) = 1.13, p = .131 [α = .025], d z = 0.13. Mean response times and error rates for the hypothesis-relevant trial types in the ignored repetition subdesign are shown in Fig. 3.

Keep in mind that for trials in the attended repetition subdesign, prime target to probe target repetitions define the different trial types: On attended repetition trials, the target location and response repeated from prime to probe, whereas on response control trials, only the correct response was repeated. There was no location or response repetition on control trials. All trial types could be implemented with a sound identity change between prime and probe target (sound-changed trials) or with a sound identity repetition (sound-repeated trials). The same testing rationale was used as in the ignored repetition subdesign.

Among sound-changed trials, repeating the target location between subsequent presentations in attended repetition trials, as well as solely reexecuting the response between prime and probe on response control trials, yielded longer response times than on control trials, t(79) = 2.94, p = .004, d z = 0.33, and t(79) = 4.30, p < .001 [α = .025] , d z = 0.48, respectively. Responding on attended repetition trials was faster, as compared with response control trials, t(79) = −2.02, p = .047 [α = .050], d z = 0.23.

For sound-repeated trials, the analysis revealed that responding in attended repetition trials was facilitated, relative to response control and control trials, t(79) = −13.21, p < .001 [α = .025], d z = 1.48, and t(79) = −11.00, p < .001, d z = 1.23, respectively. Response control and control trials did not differ, t(79) = 0.88, p = .380 [α = .050], d z = 0.10.

The analyses of the error rates led to the same pattern of statistical inferences as the reaction time data, with the only difference that accuracy was reliably lower on response control trials with sound identity repetition than on the respective control trials, t(79) = 2.68, p = .009 [α = .050], d z = 0.30.

Discussion

The present study was designed primarily to test whether distractor-related response inhibition operates in auditory selective attention as measured in the spatial negative priming task. For trials with a sound change between prime distractor and probe target, responding to an object at a previously ignored location was prolonged, as compared with other locations. This is the standard spatial negative priming effect, which can be explained by a number of different theoretical accounts (Buckolz et al., 2004; Neill & Valdes, 1992; Park & Kanwisher, 1994; Tipper et al., 1990). Comparing response control with control trials revealed that the need to execute a prior distractor response did not affect response latency. This result contradicts the prediction derived from the response inhibition account that has been put forward to explain visual spatial negative priming (Buckolz et al., 2004; Guy & Buckolz, 2007; Guy et al., 2006).

The fact that, on sound-changed trials, responses were slower on ignored repetition than on response control trials can still be explained by the location inhibition (Milliken et al., 1994; Tipper et al., 1990), the episodic retrieval account (Neill & Valdes, 1992; Neill et al., 1992), and feature mismatching account of spatial negative priming (Park & Kanwisher, 1994). The location inhibition and the episodic retrieval accounts predict impaired performance on ignored repetition trials, relative to response control trials, irrespective of whether there is a feature match or a mismatch at the repeated location between prime and probe. In contrast, the feature mismatching account implies performance on ignored repetition trials with a feature match to be equivalent to, or even better than, that on response control trials. The latter is what was found here (note that the descriptive results were parallel for the difference between ignored repetition and control trials). This result is uniquely predicted by the feature mismatching account of spatial negative priming and cannot be explained by location-based inhibition or episodic retrieval. If anything, the retrieval of inappropriate prime information should be even stronger when identical stimulus–location configurations are repeated between prime and probe displays, constituting a more efficient retrieval cue than just a repeated location. Furthermore, comparisons among sound-repeated trials revealed equivalent response times for response control and control trials, which is additional evidence against the response inhibition account of spatial negative priming.

The results are compatible with the feature mismatching account proposed by Park and Kanwisher (1994). The conclusion that feature mismatching explains spatial negative priming is also supported by other empirical studies of auditory spatial negative priming (Mayr et al., 2011; Mayr et al., 2009). At a more abstract level, these results underscore the utility of the concept of object files in auditory selective attention, and they nicely fit with the growing empirical basis of object-binding phenomena in a variety of experimental paradigms in audition (Dyson & Ishfaq, 2008; Hall, Pastore, Acker, & Huang, 2000; Maybery et al., 2009; Mondor, Zatorre, & Terrio, 1998; Parmentier, Maybery, & Elsley, 2010; Zmigrod & Hommel, 2009, 2010).

The absence of response-related aftereffects in auditory spatial negative priming differs from related findings in the visual modality (Buckolz et al., 2004; Guy & Buckolz, 2007; Guy et al., 2006) and might, therefore, be informative with respect to modality-specific mechanisms underlying target selection in the presence of distractor information. The need to execute a previously distractor-assigned response did not slow down responding. This may indicate that, in auditory selection, (1) initial activation of responses to distractors is absent (or substantially reduced), (2) distractor-related response activation is not inhibited, or (3) activation of irrelevant motor responses is indeed counteracted by an inhibitory process but produces no measurable aftereffect on responding on the subsequent trial.

With respect to the first point, the response inhibition account proposed by Buckolz et al. (2004) assumes that the activation of distractor-assigned responses is followed by inhibition, impairing the subsequent response execution. Specifically, the activation of distractor-assigned responses is a prerequisite for their subsequent inhibition. Reduced motor activation by spatially presented distractor sounds might be the consequence of a lower degree in compatibility between auditory stimuli and manual responses—as compared with the compatibility between visual stimuli and manual responses—which has been proposed for spatial tasks (Wickens, Sandry, & Vidulich, 1983; Wickens, Vidulich, & Sandry-Garza, 1984). If a distractor response was not (sufficiently) activated, it might not call for an engagement of an inhibitory process to prevent false responding. Although the absence of response activation for auditory distractor information may, in principle, account for the present finding, we think that this is not likely. Evidence from tasks presenting so-called accessory stimuli suggests that manual responses can be activated by irrelevant auditory objects, differing from the target object in identity and location. In these tasks, left and right responses are arbitrarily assigned to a nonspatial feature (e.g., color or shape) of a centrally presented visual stimulus. The visual imperative stimulus is simultaneously accompanied by an auditory accessory stimulus. This arrangement is used to evaluate the influence of spatial features of an irrelevant auditory stimulus by manipulating the relation between its spatial location and the location of the appropriate response to the imperative visual stimulus. Responding to the imperative stimulus is systematically influenced by the spatial location of the auditory accessory stimulus, yielding a Simon-like pattern of better performance if the accessory stimulus is presented at the same side as the required response, as compared with the other side (Nishimura & Yokosawa, 2009; Notebaert & Soetens, 2003, Experiment 2; Proctor, Pick, Vu, & Anderson, 2005). This pattern of results is commonly explained in terms of the dimensional overlap model (Kornblum, Hasbroucq, & Osman, 1990), assuming that the accessory stimulus automatically activates the spatially corresponding response. If the activated response conforms to the required response, response latency and accuracy are improved, while conflicting responses impair performance. Response activation seems to occur even though the stimulus is completely irrelevant to the task. This demonstrates that a task-irrelevant auditory stimulus, differing in location, identity, and even modality from the target, might nevertheless activate a spatially corresponding response. Considering this evidence, response activation by the irrelevant distractor in the spatial negative priming task seems likely.Footnote 3 As a result, the absence of motor-related inhibitory aftereffects in the task used here was most likely not due to insufficient response activation in the prime, giving rise to the possibilities that distracting motor responses are generally not inhibited or an inhibitory mechanism suppresses distractor-assigned responses but causes no impairment of their subsequent use. Note that the impact of (mis-)matching stimulus features on responding demonstrates that aftereffects could, in principle, be detected in our task. The absence of evidence for motor response inhibition while, at the same time, feature (mis-)match effects could be found might indicate different time courses of these aftereffects. Whereas memory for identity–location features survived the present prime–probe interval of 1,000 ms, aftereffects of response inhibition might be a more transient phenomenon that is too short-lived to impair future performance. This would imply that response inhibition takes place but is presumably of no major consequence for subsequent responding. Although the present experiment cannot readily be used to ultimately decide whether inhibition is transient or absent in auditory selection, we argue in favor of the latter alternative. This argumentation is primarily based on a recent auditory spatial negative priming study—comparable to the one by Mayr et al. (2011)—in which we manipulated the response–stimulus interval (RSI) between prime response and probe target sounds, with RSIs of 100, 750, or 1,400 ms. We reasoned that, if response inhibition is indeed present but transient, it should selectively affect probe responding after short RSIs. However, we found that responding was equivalent for all RSI levels, and the response behavior was exclusively determined by feature mismatches, which further supports the idea that auditory selection is not achieved by inhibitory processes. In sum, our data can be taken as evidence that inhibition does not affect distractor-related motor responses, at least not in a way that slows the subsequent reuse of these responses.

On the basis of findings in the visual modality, the spatial negative priming effect has been explained in terms of an inhibition of return (IOR) mechanism (for reviews, see Klein, 2000; Taylor & Klein, 1998). In essence, the IOR explanation of the spatial negative priming effect assumes that spatial attention is directed to target, as well as distractor stimuli, during the prime presentation, followed by an inhibitory process that prevents the subsequent reorientation of attention, leading to impaired stimulus processing at all previously occupied locations in the probe. In accordance with this explanation, Christie and Klein (2001) and Milliken et al. (2000) found impaired performance in a visuospatial negative priming task when the probe target was presented at a location that contained target or distractor stimuli during the prime (see Christie & Klein, 2008, for the crucial role of target repetition trials in testing theories of spatial negative priming). However, such an IOR-consistent pattern of results has not always been found for attended repetition trials in visuospatial priming tasks (see Guy et al., 2006).

Turning to the present auditory priming task, note that the pattern of results in the ignored repetition subdesign was not compatible with an IOR account of auditory spatial negative priming, because there was no general decline in performance when the probe target appeared at the previously ignored location. Instead, performance declined when a feature mismatch was present at that location. Thus, it appears that IOR was not involved, or at least did not determine performance, on the ignored repetition trials of the present task.

At odds with an IOR explanation and different from findings in the visual modality (Christie & Klein, 2001; Milliken et al., 2000), presenting the probe target at the location of the former prime target did not generally impair responding in the present auditory task. In fact, a full repetition of sound, location, and response features between successive target stimuli had a strong facilitative effect on performance, as compared with the respective control condition. All other conditions in the attended repetition subdesign that contained only partial repetitions—that is, response control trials with a sound and response repetition but a location change, response control trials with a response repetition but a sound and location change, and attended repetition trials with a location and response repetition but a sound change—resulted in impaired performance, relative to their respective control trials.

Milliken et al. (2000) argued that IOR effects might be (sometimes) counteracted by facilitative repetition effects of nonspatial stimulus features (such as color in the visual modality or, in the present auditory task, sound identity and also response features). However, a facilitative nonspatial feature repetition effect overcompensating for a slowdown due to IOR cannot account for the present facilitative effect on full repetition trials, since the corresponding control trials also comprised sound, as well as response repetitions, between successive targets. Therefore, neither the findings of the ignored repetition subdesign nor the results of the attended repetition subdesign are compatible with the IOR account that predicts impaired responding to all previously occupied locations.

The results from the attended repetition subdesign are also incompatible with the assumption that feature dimensions are processed independently. If this were true, response facilitation in attended repetition trials should have gradually increased with the number of repeated features. Instead, the overall pattern of results is most parsimoniously explained by assuming auditory event file binding, extending the concept of object files to include response information (Zmigrod & Hommel, 2009, 2010). Within this framework, presenting individual features of the prior episode retrieves all features of the respective event file, leading to impaired performance whenever the retrieved information does not meet the perceptual or response-related requirements of the current situation. This is the case in partial repetitions. In contrast, responding is assumed to be facilitated if stimuli fully match in all features from the prior episode. The prediction of impaired performance for partial and improved performance for full repetitions is, overall, supported by the results of the attended repetition design and, therefore, stresses the impact of binding processes in the auditory domain and the explanation of the results in the ignored repetition design in terms of the feature mismatching hypothesis (Park & Kanwisher, 1994).

Beyond showing that auditory spatial negative priming can be explained exclusively by feature mismatching (and not by response inhibition, location inhibition, or episodic retrieval), the present results contribute to the understanding of processes underlying spatial selective attention in audition in general. First, inhibition of distractor-related motor responses does not seem to be a relevant mechanism of auditory selective attention. Second, further evidence of the formation of auditory object files was found, supporting object binding as a general coding principle even for to-be-ignored distractor events (Mayr et al., 2011; Mayr et al., 2009; Zmigrod & Hommel, 2009, 2010). Nevertheless, the conditions under which feature mismatches affect behavior are still under investigation. As for identity-based negative priming tasks—in which responding is determined by the stimulus identity of a sound—location–identity mismatch effects are usually not found (e.g., Banks et al., 1995; Buchner & Mayr, 2004; Buchner & Steffens, 2001; Mondor, Leboe, & Leboe, 2005). This means that the slowdown in responding to a previously ignored sound identity does not depend on whether the repeated sound is presented at the same or another location (e.g., ear) in the prime and probe. However, it is possible that the absence of feature mismatch effects in auditory identity negative priming is due to the minor relevance of location information in these tasks. In favor of this idea, location–identity mismatch effects are found in identity negative priming tasks when spatial aspects of the stimulus presentation are made more available during sound processing. For example, in the study of Mayr et al. (2011; see also Leboe, Mondor, & Leboe, 2006), participants identified a target sound in the presence of a simultaneous distractor presented from another of four spatially separated loudspeakers. By using speakers instead of headphones, binaural localization cues were available in a presumably more naturalistic format to aid the processing of spatial sound features. The authors argued that, if the processing of spatial sound characteristics is possible, effects of identity–location mismatches emerge, whereas they might not appear otherwise. In conclusion, feature mismatches seem to be an important but not mandatory characteristic of auditory processing and might be influenced by the significance of spatial attributes in the task at hand.

Notes

Note that the same rationale would also hold if not both but only one of the two distractor-assigned responses were activated and subsequently inhibited during the prime presentation of response control trials. However, see Buckolz et al. (2004) for evidence of response activation and subsequent inhibition of both responses.

Note that the influence of response inhibition can only be unambiguously assessed with centrally presented stimuli. For parafoveal stimuli, a potential response inhibition mechanism would possibly come along with an additional mechanism producing an inhibition-of-return effect (e.g., Rafal, Calabresi, Brennan, & Sciolto, 1989; Rafal, Davies, & Lauder, 2006).

There are several differences between the accessory and the spatial negative priming task. The spatial negative priming task presents auditory targets simultaneously with auditory distractors, while in the accessory task a single distractor sound accompanies a visual target stimulus. In addition, spatial location is a relevant stimulus feature in the spatial negative priming task, while it is completely irrelevant in the Simon-like accessory task. However, these differences might even argue for a stronger degree of response activation associated with distractor stimuli in the spatial negative priming task than in the accessory task. This should be so because an even stronger response activation by irrelevant stimuli might emerge when location becomes a response-relevant dimension and when target and distractor stimuli cannot be distinguished easily by their modality.

References

Banks, W. P., Roberts, D., & Ciranni, M. (1995). Negative priming in auditory attention. Journal of Experimental Psychology. Human Perception and Performance, 21, 1354–1361.

Buchner, A., & Mayr, S. (2004). Auditory negative priming in younger and older adults. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. A, Human Experimental Psychology, 57A, 769–787.

Buchner, A., & Steffens, M. C. (2001). Auditory negative priming in speeded reactions and temporal order judgements. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. A, Human Experimental Psychology, 54A, 1125–1142.

Buckolz, E., O'Donnell, C., & McAuliffe, J. (1996). The Simon effect: Evidence of a response processing "functional locus" Aug 1996. Human Movement Science, 15, 543–564.

Buckolz, E., Goldfarb, A., & Khan, M. (2004). The use of a distractor-assigned response slows later responding in a location negative priming task. Perception & Psychophysics, 66, 837–845.

Buckolz, E., Avramidis, C., & Fitzgeorge, L. (2008). Prime-trial processing demands and their impact on distractor processing in a spatial negative priming task. Psychological Research/Psychologische Forschung, 72, 235–248.

Chao, H.-F. (2009). Revisiting the role of probe distractors in negative priming: Location negative priming is observed when probe distractors are consistently absent. Attention, Perception, & Psychophysics, 71, 1072–1082.

Christie, J., & Klein, R. M. (2001). Negative priming for spatial location? Canadian Journal of Experimental Psychology/Revue canadienne de psychologie experimentale, 55, 24–38.

Christie, J., & Klein, R. M. (2008). On finding negative priming from distractors. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 15, 866–873.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Hillsdale: Erlbaum.

Coles, M. G. H., Gratton, G., Bashore, T. R., Eriksen, C. W., & Donchin, E. (1985). A psychophysiological investigation of the continuous flow model of human information processing. Journal of Experimental Psychology. Human Perception and Performance, 11, 529–553.

De Jong, R., Liang, C.-C., & Lauber, E. (1994). Conditional and unconditional automaticity: A dual-process model of effects of spatial stimulus-response correspondence. Journal of Experimental Psychology. Human Perception and Performance, 20, 731–750.

Dyson, B. J., & Ishfaq, F. (2008). Auditory memory can be object based. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 15, 409–412.

Eimer, M. (1999). Facilitatory and inhibitory effects of masked prime stimuli on motor activation and behavioural performance. Acta Psychologica, 101, 293–313.

Eimer, M., Schubö, A., & Schlaghecken, F. (2002). Locus of inhibition in the masked priming of response alternatives. Journal of Motor Behavior, 34, 3–10.

Eriksen, C. W., Coles, M. G. H., Morris, L. R., & O'Hara, W. P. (1985). An Electromyographic Examination of Response Competition. Bulletin of the Psychonomic Society, 23, 165–168.

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A.-G., & Buchner, A. (2007). G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 39, 175–191.

Fitzgeorge, L., & Buckolz, E. (2008). Spatial negative priming modulation: The influence of probe-trial target cueing, distractor presence, and an intervening response. European Journal of Cognitive Psychology, 20, 994–1026.

Fitzgeorge, L., Buckolz, E., & Khan, M. (2011). Recently inhibited responses are avoided for both masked and nonmasked primes in a spatial negative priming task. Attention, Perception, & Psychophysics, 73, 1435–1452.

Fox, E. (1995). Negative priming from ignored distractors in visual selection: A review. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 2, 145–173.

Guy, S., & Buckolz, E. (2007). The locus and modulation of the location negative priming effect. Psychological Research, 71, 178–191.

Guy, S., Buckolz, E., & Pratt, J. (2004). The Influence of Distractor-Only Prime Trials on the Location Negative Priming Mechanism. Experimental Psychology, 51, 4–14.

Guy, S., Buckolz, E., & Khan, M. (2006). The locus of location repetition latency effects. Canadian Journal of Experimental Psychology, 60, 307–318.

Hall, M. D., Pastore, R. E., Acker, B. E., & Huang, W. (2000). Evidence for auditory feature integration with spatially distributed items. Perception & Psychophysics, 62, 1243–1257.

Holm, S. (1979). A Simple Sequentially Rejective Multiple Test Procedure. Scandinavian Journal of Statistics, 6, 65–70.

Kahneman, D., Treisman, A., & Gibbs, B. J. (1992). The reviewing of object files: Object-specific integration of information. Cognitive Psychology, 24, 175–219.

Klein, R. M. (2000). Inhibition of return. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 4, 138–147.

Kornblum, S., Hasbroucq, T., & Osman, A. (1990). Dimensional Overlap - Cognitive Basis for Stimulus-Response Compatibility - a Model and Taxonomy. Psychological Review, 97, 253–270.

Leboe, J. P., Mondor, T. A., & Leboe, L. C. (2006). Feature mismatch effects in auditory negative priming: Interference as dependent on salient aspects of prior episodes. Perception & Psychophysics, 68, 897–910.

Maybery, M. T., Clissa, P. J., Parmentier, F. B. R., Leung, D., Harsa, G., Fox, A. M., & Jones, D. M. (2009). Binding of verbal and spatial features in auditory working memory. Journal of Memory and Language, 61, 112-133.

Mayr, S., & Buchner, A. (2007). Negative priming as a memory phenomenon: A review of 20 years of negative priming research. Zeitschrift für Psychologie - Journal of Psychology, 215, 35–51.

Mayr, S., Hauke, R., & Buchner, A. (2009). Auditory location negative priming: A case of feature mismatch. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 16, 845–849.

Mayr, S., Buchner, A., Möller, M., & Hauke, R. (2011). Spatial and identity negative priming in audition: Evidence of feature binding in auditory spatial memory. Attention, Perception, & Psychophysics, 73, 1710–1732.

Milliken, B., Tipper, S. P., & Weaver, B. (1994). Negative priming in a spatial localization task: Feature mismatching and distractor inhibition. Journal of Experimental Psychology. Human Perception and Performance, 20, 624–646.

Milliken, B., Tipper, S. P., Houghton, G., & Lupiáñez, J. (2000). Attending, ignoring, and repetition: On the relation between negative priming and inhibition of return. Perception & Psychophysics, 62, 1280–1296.

Mondor, T. A., Zatorre, R. J., & Terrio, N. A. (1998). Constraints on the selection of auditory information. Journal of Experimental Psychology. Human Perception and Performance, 24, 66–79.

Mondor, T. A., Leboe, J. P., & Leboe, L. C. (2005). The role of selection in generating auditory negative priming. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 12, 289–294.

Neill, W. T., & Valdes, L. A. (1992). Persistence of negative priming: Steady-state or decay? Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 18, 565–576.

Neill, W. T., Valdes, L. A., Terry, K. M., & Gorfein, D. S. (1992). Persistence of negative priming: II. Evidence for episodic trace retrieval. Journal of Experimental Psychology-Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 18, 993–1000.

Nishimura, A., & Yokosawa, K. (2009). Effects of laterality and pitch height of an auditory accessory stimulus on horizontal response selection: The Simon effect and the SMARC effect. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 16, 666–670.

Notebaert, W., & Soetens, E. (2003). Irrelevant auditory attention shifts prime corresponding responses. Psychological Research, 67, 253–260.

Park, J., & Kanwisher, N. (1994). Negative priming for spatial locations: Identity mismatching, not distractor inhibition. Journal of Experimental Psychology. Human Perception and Performance, 20, 613–623.

Parmentier, F. B. R., Maybery, M. T., & Elsley, J. (2010). The involuntary capture of attention by novel feature pairings: A study of voice-location integration in auditory sensory memory. Attention, Perception, & Psychophysics, .72, pp.

Proctor, R. W., Pick, D. F., Vu, K.-P. L., & Anderson, R. E. (2005). The enhanced Simon effect for older adults is reduced when the irrelevant location information is conveyed by an accessory stimulus. Acta Psychologica, 119, 21–40.

Rafal, R., Calabresi, P. A., Brennan, C. W., & Sciolto, T. K. (1989). Saccade preparation inhibits reorienting to recently attended locations. Journal of Experimental Psychology. Human Perception and Performance, 15, 673–685.

Rafal, R., Davies, J., & Lauder, J. (2006). Inhibitory tagging at subsequently fixated locations: Generation of "inhibition of return" without saccade inhibition. Visual Cognition, .13, pp.

Ridderinkhof, K. R. (2002). Activation and suppression in conflict tasks: empirical clarification through distributional analyses. Common Mechanisms in Perception and Action, 19, 494–519.

Smid, H. G., Mulder, G., & Mulder, L. J. (1990). Selective response activation can begin before stimulus recognition is complete: A psychophysiological and error analysis of continuous flow. Acta Psychologica, 74, 169–201.

Taylor, T. L., & Klein, R. M. (1998). On the causes and effects of inhibition of return. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 5, 625–643.

Tipper, S. P. (2001). Does negative priming reflect inhibitory mechanisms? A review and integration of conflicting views. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. A, Human Experimental Psychology, 54A, 321–343.

Tipper, S. P., Brehaut, J. C., & Driver, J. (1990). Selection of moving and static objects for the control of spatially directed action. Journal of Experimental Psychology. Human Perception and Performance, 16, 492–504.

Tipper, S. P., Weaver, B., & Milliken, B. (1995). Spatial negative priming without mismatching: Comment on Park and Kanwisher (1994). Journal of Experimental Psychology. Human Perception and Performance, 21, 1220–1229.

Valle-Inclán, F., & Redondo, M. (1998). On the automaticity of ipsilateral response activation in the Simon effect. Psychophysiology, 35, 366–371.

Wickens, C. D., Sandry, D. L., & Vidulich, M. (1983). Compatibility and resource competition between modalities of input, central processing, and output. Human Factors, 25, 227–248.

Wickens, C. D., Vidulich, M., & Sandry-Garza, D. (1984). Principles of S-C-R compatibility with spatial and verbal tasks: The role of display-control location and voice-interactive display-control interfacing. Human Factors, 26, 533–543.

Zmigrod, S., & Hommel, B. (2009). Auditory event files: Integrating auditory perception and action planning. Attention, Perception, & Psychophysics, 71, 352–362.

Zmigrod, S., & Hommel, B. (2010). Temporal dynamics of unimodal and multimodal feature binding. Attention, Perception, & Psychophysics, 72, 142–152.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Author Notes

Malte Möller, Susanne Mayr, and Axel Buchner, Department of Experimental Psychology, Heinrich-Heine-Universität Düsseldorf, Germany. The research reported in this article was supported by a grant from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (Ma 2610/2-2). We thank Juliane Weber for her assistance with data collection.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Möller, M., Mayr, S. & Buchner, A. Target localization among concurrent sound sources: No evidence for the inhibition of previous distractor responses. Atten Percept Psychophys 75, 132–144 (2013). https://doi.org/10.3758/s13414-012-0380-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.3758/s13414-012-0380-2