Abstract

Salient visual singleton stimuli produce spatial cueing effects indicative of attentional capture only when they match current task sets, suggesting that capture is subject to top-down control. However, such task-set contingent capture effects could be associated with the top-down controlled disengagement of attention from non-matching stimuli that follows their initial bottom-up salience-driven selection. Using the N2pc component as an event-related potential marker of attentional capture, we demonstrate that top-down task set already controls the initial rapid selection of salient visual singleton stimuli prior to any subsequent attentional disengagement. These findings provide new evidence for the primacy of top-down control over bottom-up salience in attentional capture.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Our visual system has evolved to detect and identify currently relevant objects. Attentional mechanisms play a critical role in visual cognition because they determine which of the many objects that are simultaneously present in the visual world are selected as targets for eye movements, in-depth analysis, and identification. A critical question is whether the attentional selection of visual objects is fully under endogenous top-down control or whether properties of the visual world dictate which objects are selected. Some have claimed that top-down control drives the allocation of attention to different parts of the visual input from the very start (cf. Bichot, Rossi, & Desimone, 2005). Others have argued that endogenous control of attentional selection can only be exerted after an initial phase during which visual stimuli attract attention in an exogenous bottom-up fashion that is determined by salience alone (cf. Bergen & Julesz, 1983; Itti & Koch, 2001).

Results from visual search experiments have suggested that perceptually salient but task-irrelevant visual events can capture attention independently of current top-down task sets. When participants search for a shape-defined singleton target among non-target shapes (such as a diamond target among circle distractors), reaction times (RTs) are delayed when a salient but task-irrelevant color singleton is present relative to trials without an additional color distractor (e.g., Theeuwes, 1992). This indicates that color singletons capture attention due to their bottom-up salience and irrespective of current search intentions. However, other studies (e.g., Folk & Remington, 1998; Folk, Remington, & Johnston, 1992; Folk, Remington, & Wright, 1994) have demonstrated that the ability of salient visual events to capture attention is determined by top-down task sets. When spatially uninformative singleton cues precede visual search displays, faster RTs for visual search targets at cued locations indicate attentional capture by these cues. Critically, such spatial cueing effects are only present when cues share features with currently task-relevant stimuli (e.g., red color singleton cues in blocks where targets are also red), but not when cue features are task-irrelevant. Based on such findings, Folk et al. (1992) proposed their contingent involuntary orienting hypothesis, which postulates that salient visual feature singletons capture attention only when their features match an active top-down attentional setting. Once such a control setting is established (via experimental instructions that specify target-defining visual features), stimuli that share critical properties will attract attention even when they are known to be task-irrelevant (hence ‘involuntary’ orienting).

The hypothesis that attention is captured in a bottom-up fashion by salient visual singletons regardless of their task relevance (Theeuwes, 1992) appears at odds with the observation that spatial cueing effects indicative of attentional capture are absent when singleton cues do not share attributes with targets (Folk et al., 1992). However, Theeuwes and colleagues (Belopolsky, Schreij, & Theeuwes, 2010; Theeuwes, 2010; Theeuwes, Atchley, & Kramer, 2000) have claimed that bottom-up attentional capture is perfectly consistent with results such as those observed by Folk et al. (1992). They argue that visually salient singleton stimuli will always capture attention, regardless of whether they match a currently active task set. Contingent capture effects are the result of top-down control mechanisms that affect selective attentional processing after the initial salience-driven attentional capture. According to Theeuwes (2010), “the primary role of the top-down set is to control the disengagement of attention from the features that do not match it” (p.18). When cue arrays precede target displays, attentional disengagement from non-matching cues is already completed when target displays are presented, and the absence of behavioral spatial cueing effects for these cues therefore does not reflect the absence of bottom-up attentional capture, but instead the subsequent impact of top-down control.

The contingent involuntary orienting hypothesis and the alternative rapid disengagement hypothesis make very different assumptions about the exact time course of the bottom-up versus top-down control of attentional selection. Because event-related potential (ERP) measures provide a precise millisecond-by-millisecond record of selective attentional processing, such measures can yield new insights that could help to resolve this debate. The N2pc component is an enhanced negativity at posterior electrodes contralateral to the visual field where a candidate target stimulus is presented, typically emerges around 200 ms after stimulus onset, and is thought to reflect the spatially selective attentional processing of target objects among distractors in visual search tasks (Luck & Hillyard, 1994; see also Eimer, 1996). This component provides a useful tool to study bottom-up and top-down factors during selective visual attention, and has already been employed in several recent studies of attentional capture, and on both sides of the top-down/bottom-up debate (e.g., Ansorge, Kiss, & Eimer, 2009; Eimer & Kiss, 2010a; Eimer, Kiss, Press, & Sauter, 2009; Hickey, McDonald, & Theeuwes, 2006; Jolicœur, Sessa, Dell'Acqua, & Robitaille, 2006; Kiss, Jolicœur, Dell'Acqua, & Eimer, 2008; Lien, Ruthruff, Goodin, & Remington, 2008; Mazza, Turatto, Umiltà, & Eimer, 2007; Wykowska & Schubö, in press).

An N2pc indicative of attentional capture was triggered by perceptually salient but spatially uninformative color singleton cues when participants searched for targets in the same color, but not when a different dimension was task-relevant (Eimer & Kiss, 2008; see also Eimer et al., 2009, for ERP evidence that such task-set contingent capture effects are the result of feature-specific top-down task sets). If the initial capture of attention by color singleton cues were entirely driven by bottom-up salience, they should have triggered an N2pc regardless of whether or not they matched the currently active attentional control setting. This was not the case, which suggests that the initial attentional selection of visual objects is contingent on currently active task sets. However, this conclusion only holds if the N2pc component is indeed a valid electrophysiological marker of rapid attentional selection. According to Theeuwes (2010), the N2pc does not meet this requirement, because it is not associated with attentional capture, but instead with a later stage of in-depth attentional processing of visual objects that follows their initial attentional selection. According to this line of reasoning, the observation that perceptually salient visual stimuli that do not match the current attentional control setting fail to trigger an N2pc (e.g., Eimer & Kiss, 2008) cannot provide conclusive evidence against bottom-up attentional capture, because the absence of an N2pc to these stimuli is consistent with the alternative hypothesis that attention was initially captured, but then rapidly disengaged.

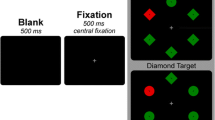

In summary, the question whether the effects of top-down task set on behavioral spatial cueing effects and on the N2pc reflect contingent involuntary attentional capture or the subsequent top-down controlled attentional disengagement from stimuli that do not match current target-defining features remains unresolved. The logic adopted in the present experiment was to introduce a strong experimental manipulation of top-down attentional disengagement strategies. If the effects of top-down task set on behavior and the N2pc observed in previous studies are indeed due to differential disengagement, they should be strongly modulated by this manipulation. In contrast, effects produced by contingent involuntary attentional capture should remain unaffected. The procedure was similar to the one introduced by Folk et al. (1992). Color singleton cues preceded visual search arrays that contained one color singleton target, and singleton cues either matched or did not match the attentional control setting for the current target color (see Fig. 1). The critical manipulation concerned the spatial information that the singleton cue provided with respect to the location of the subsequent target. In one set of successively presented blocks, cue and target locations were uncorrelated (uninformative cue condition). In another blocked condition, targets were always presented at the position that was previously occupied by the color cue (100% same position condition). In a third blocked condition, cues and targets always appeared at diagonally opposite positions (100% different position condition). Participants were informed of these cue-target location contingencies and were encouraged to use them to guide target detection. The stimulus onset asynchrony between cue and target arrays was 200 ms, which is sufficient to measure the N2pc in response to the cue prior to any sensory-evoked ERP activity triggered by the subsequent target array. The cue-elicited N2pc was measured as a marker of attentional capture, separately for matching and non-matching cues, and for the three different cue informativeness conditions.

Example of the sequence of events in an SP (same cue-target position) trial with target-color matching singleton cue (top) and in a DP (different cue-target positions) trial with non-matching color singleton cue (bottom). Cue and target arrays contained one color singleton among grey items. Target-color matching and non-matching color singletons are shown in white with black outline and in black with white outline, respectively

For spatially uninformative cues, results were expected to mirror previous findings (e.g., Eimer & Kiss, 2008; Eimer et al., 2009). A behavioral spatial cueing effect indicative of attentional capture and an N2pc should be observed for trials in which color singleton cues matched the current attentional control setting for target color. For non-matching cues, these effects should be strongly attenuated or entirely absent. The critical question concerned the impact of top-down color task set on behavioral spatial cueing effects and on the N2pc in blocks with spatially informative cues. In the 100% same position (SP) condition, where the target was known to appear always at the cued location, participants had every incentive to maintain attention at this location and no reason to initiate any top-down controlled attentional disengagement. In the 100% different position (DP) condition, participants knew that color singleton cues and targets were always presented at diagonally opposite positions, and therefore had a strong top-down incentive to rapidly disengage attention from these cues, and direct it towards the opposite visual quadrant.

Because the rapid disengagement of attention is under top-down control (Theeuwes, 2010), attentional disengagement from cued locations should be completely absent in 100% SP blocks, but be elicited on virtually every trial in 100% DP blocks. Importantly, this was the case regardless of whether cues matched or did not match the current target color. If the impact of color task set on behavioral spatial cueing effects was due to the top-down controlled disengagement from non-matching cues, this difference should therefore be abolished both in the 100% SP condition and in the 100% DP condition. In the 100% SP condition, attention should not be disengaged from any cues, regardless of their color. In the 100% DP condition, attention should be rapidly disengaged from matching as well as from non-matching cues. According to the contingent involuntary attentional capture hypothesis (Folk et al., 1992), once a top-down color set is established via task instructions, rapid attentional capture is involuntary in the sense that it is determined solely by whether a stimulus matches the current task set for target features, but not by other strategic factors. Therefore, behavioral spatial cueing effects in the 100% SP and 100% DP conditions should be task-set contingent, similar to the effects found with uninformative cues.

If the N2pc component does not reflect rapid attentional selection, but instead processing that follows the initial selection of visual objects, and if the absence of an N2pc to salient visual stimuli that do not match the current task set is due to rapid disengagement from those stimuli (Theeuwes, 2010), N2pc results should differ dramatically between 100% SP and 100% DP blocks. In 100% SP blocks, no attentional disengagement from cued locations is expected for either matching or non-matching cues, and an N2pc of similar size should be triggered by both types of cues. In 100% DP blocks, no N2pc is expected for either type of cue, since rapid attentional disengagement from all cues will prevent the emergence of an N2pc that is associated with post-selective attentional processing. In contrast, the contingent involuntary attentional capture hypothesis predicts a similar pattern of N2pc results in the 100% SP and 100% DP conditions: An N2pc should be observed for matching cues, but will be strongly attenuated or absent for non-matching cues. While the difference between 100% SP and 100% DP cues should have some impact on later stages of their attentional processing, contingent involuntary capture implies that any such effects will only emerge later, after the initial color-contingent attentional selection.

Method

Participants

Seventeen volunteers were paid to participate in this study. One of them was excluded because response errors occurred on more than 10% of all trials. The remaining 16 participants (6 male, aged 19–28 years; mean age 22 years) all had normal or corrected-to-normal vision.

Stimuli and procedure

Stimuli were presented on a 17” Sony TFT LCD monitor (60 Hz refresh rate; 16 ms black-to-white-to-black response time, as verified with a photodiode) against a black background. On each trial, a cue display was presented for 50 ms and was followed after a 150-ms blank interval by a 50-ms presentation of the search display (see Fig. 1). Each cue display contained a circular array of six sets of four dots. Each set of dots subtended an 0.8° × 0.8° visual angle and was presented at a distance of 4.4° from a central grey fixation point. Five sets of dots were grey (CIE color coordinates = 0.281/0.303), and the remaining set of dots was a color singleton. Two different equiprobable color singleton cues were employed for each participant—one that matched the current target color, and one that did not match the target color. These two possible cue colors were selected from a set of six different colors: red (0.640/0.347), green (0.261/0.561), yellow (0.449/0.455), purple (0.298/0.147), turquoise (0.210/0.310), and blue (0.151/0.107). The selection of matching and non-matching cue colors was counterbalanced across participants. Color singleton cues appeared randomly and equiprobably at one of the four lateral positions in the left or right hemifield, but never at the top or bottom positions.

Search displays consisted of circular arrays of six equidistant horizontal or vertical bars (each subtending 1.3° × 0.5°) that were presented at the same location as the preceding cue array elements (4.4° from fixation). Each search display contained three horizontal and three vertical bars. Five of these were grey distractor bars, and the remaining bar was a color singleton target. Target color was chosen from one of the six colors defined above, remained constant for each participant, and was counterbalanced across participants, with the exception that turquoise or purple served as target colors for only two participants. Targets appeared randomly and equiprobably at one of the four lateral positions, but never at the top or bottom positions. Grey and colored stimuli in the cue and search displays were all equiluminant (11 cd/m2). The interval between search array offset and the onset of the cue array on the next trial was 1,500 ms. Participants were instructed to maintain central fixation, to detect the color singleton target bar, and to report its orientation (horizontal or vertical) by pressing one of two vertically arranged response keys with their left or right hand. Hand-to-key assignment was balanced across participants.

Design

The experiment consisted of three blocked conditions that only differed with respect to the spatial relationship between color singleton cues and targets. In blocks with spatially uninformative cues, cue and target positions were uncorrelated. In 100% SP blocks, the target singleton always appeared at the same position as the preceding color singleton cue. In 100% DP blocks, the target was always presented at the position that was diagonally opposite to the position of the color cue. In all three blocked conditions, trials with cues that matched the target color and trials with non-matching cues were equiprobable and presented in random order.

Each of the three blocked conditions included six successively presented blocks with 64 trials per block. Every block contained four trials for each of the 16 combinations of the four possible target positions (upper left; lower left; upper right; lower right), two target orientations (horizontal, vertical), and two cue colors (matching; non-matching). Prior to the start of each blocked condition, participants were informed about the spatial relationship between cue and target positions in the upcoming blocks and how this relationship could be used to guide target localization. One practice block, containing 64 trials, preceded the six experimental blocks in each of the three conditions. The six different possible sequences of the three blocked conditions were balanced across the 16 participants. Six participants started with the uninformative blocks, and five participants started with the 100% SP and the 100% DP blocks, respectively.

EEG recording and analysis

EEG was DC-recorded from 23 scalp electrodes mounted in an elastic cap at standard positions of the extended 10/20 system at sites Fpz, Fz, F3, F4, F7, F8, FC5, FC6, Cz, C3, C4, T7, T8, CP5, CP6, Pz, P3, P4, P7, P8, PO7, PO8, and Oz. The continuous EEG was sampled at a rate of 500 Hz with a digital low-pass filter of 40 Hz. All electrodes were online referenced to the left earlobe and re-referenced offline to the average of both earlobes. No further filters were applied after EEG acquisition. Only trials with correct responses to targets were analyzed. These trials were segmented from 100 ms before to 400 ms after cue onset. Trials with artifacts (HEOG exceeding ±30 μV; Fpz ±60 μV; all other electrodes ±80 μV), or with incorrect or missing responses to targets were excluded from all further analyses. EEG was averaged for all combinations of cue validity (uninformative; 100% SP cue; 100% DP cue), cue color (target-color matching; non-matching), and cue side (left vs. right visual field), collapsed across all color singleton target locations. The N2pc to color singleton cues was quantified on the basis of mean amplitudes obtained in a 220-280-ms time window after cue onset at lateral posterior electrodes PO7 and PO8. N2pc mean amplitudes were analyzed in repeated-measures ANOVAs for the factors cue validity, cue color, cue side, and laterality (electrode contralateral vs. ipsilateral to the visual field of the color singleton cue).

Results

Behavioral performance

Figure 2 shows RTs for correct responses and error rates observed in blocks with spatially uninformative and spatially informative cues, separately for the two different cue colors (target-color matching or non-matching; solid and dashed lines), and for trials/blocks where cues and targets were located at the same position (SP) or at different positions (DP). Out of all trials, 4.1% were eliminated from analyses because RTs differed from the individual mean correct RT of the respective condition by more than two standard deviations. In blocks with uninformative cues, RTs were faster on SP than on DP trials (main effect of cue-target position: F[1, 15] = 44.66, p < 0.01). As expected, this spatial cueing effect was much larger for matching cues than for non-matching cues (cue color × cue-target position interaction: F[1, 15] = 9.31, p < 0.01). Follow-up analyses revealed a reliable spatial cueing effect indicative of attentional capture for matching cues (38 ms, t[15] = 6.24, p < 0.01). For non-matching cues, this effect was smaller (10 ms) and did not reach significance, t(15) = 1.79, p = 0.09. The analysis of blocks with spatially informative cues confirmed that RTs were faster in 100% SP blocks than in 100% DP blocks (main effect of cue-target position: F[1, 15] = 40.65, p < 0.01). Critically, even though this effect was significant for both matching and non-matching cues, both t(15) > 4.8, both p < 0.01, it was much larger for matching than for non-matching cues (61 ms versus 36 ms, see Fig. 2), and this was reflected in a cue color × cue-target position interaction, F(1, 15) = 22.91, p < 0.01. There was also an almost significant trend towards faster RTs on trials with matching as compared to non-matching cues, F(1, 15) = 4.10, p = 0.06.

Reaction times (RTs; left panels) and error rates (right panels) for spatially uninformative and spatially informative cues, separately for the two different cue colors (target-color matching or non-matching; solid and dashed lines), and for trials/blocks where cues and targets were located at the same position (SP) or at different positions (DP)

To further confirm that behavioral attentional capture effects were modulated by top-down task set for target color not just when cues were spatially uninformative, but also for informative cues, an omnibus ANOVA including the additional variable cue informativeness (informative vs. uninformative) was conducted. As would be expected, RTs were faster in blocks with informative cues relative to uninformative-cue blocks (main effect of cue informativeness: F[1, 15] = 53.13, p < 0.01), confirming that participants used spatially informative cues to guide their attention. The RT difference between SP and DP blocks with informative cues was larger than the corresponding RT difference between SP and DP trials in blocks with uninformative cues (cue-target position × cue informativeness interaction: F[1, 15] = 14.33, p < 0.01). There was also a main effect of cue-target position, F(1, 15) = 53.13, p < 0.01, and an interaction between cue color and cue-target position, F(1, 15) = 21.16, p < 0.01, reflecting faster RTs on SP relative to DP trials, and the fact that this RT difference was more pronounced with matching cues. Most importantly, there was no indication of any three-way interaction among cue color, cue-target position, and cue informativeness (F < 1.00), demonstrating that task-set contingent modulations of spatial cueing effects were of comparable magnitude in blocks with spatially uninformative and spatially informative cues.

Error rates showed the same overall pattern as the RT effects (Fig. 2). An ANOVA of arc-sine transformed error rates in blocks with uninformative cues obtained an almost significant effect of cue-target position, F(1, 15) = 3.94, p = 0.07, reflecting a trend towards more errors on DP trials, but no overall significant cue color × cue target position interaction, F(1, 15) = 1.69, p = 0.21. In blocks with informative cues, a significant main effect of cue-target position, F(1, 15) = 5.23, p < 0.05, was accompanied by a cue color × cue-target position interaction, F(1, 15) = 5.11, p < 0.05, as errors were more frequent in DP as compared to SP blocks when cues were matching, t(15) = 2.77, p < 0.05, whereas there was no such difference with non-matching cues, t(15) = 1.01, p = 0.30.

N2pc. Figure 3 shows ERPs elicited at electrodes PO7/8 contralateral and ipsilateral to the position of a color singleton cue in the 300-ms interval after cue array onset. ERPs are shown separately for trials with matching and non-matching cues, and for blocks with uninformative cues, for 100% SP blocks, and for 100% DP blocks, respectively. It is obvious from Fig. 3 that a clear N2pc was triggered by target-color matching cues in all thee types of blocks. For non-matching cues, the N2pc was substantially attenuated. N2pc differences associated with the spatial information provided by the cues were more subtle, and can be seen most easily in the difference waveforms shown in Fig. 4. These difference waves were computed by subtracting ERPs at electrodes ipsilateral to the side of the color cue from contralateral ERPs, separately for trials with matching cues (black lines) and non-matching cues (grey lines), and for the three-blocked cue-target position conditions (uninformative cues, 100% SP cues, 100% DP cues, represented by dashed, thick, and thin lines). Figure 4 demonstrates that N2pc modulations associated with the difference between matching and non-matching cues were larger and emerged earlier than N2pc differences linked to the spatial informativeness of the cues.

Grand-average ERPs obtained at electrodes PO7/8 contralateral (dashed lines) and ipsilateral (solid lines) to the position of a color singleton cue in the 300-ms interval after cue array onset. ERPs are shown separately for trials with matching (top panels) and non-matching cues (bottom panels), and for blocks with uninformative cues (left panels), 100% SP blocks (middle panels), and 100% DP blocks (right panels), respectively

Difference waves obtained by subtracting ERPs elicited at electrodes PO7/8 ipsilateral to the cue location from contralateral ERPs. Difference waves are shown separately for target-color matching (black lines) and non-matching cues (grey lines), and for blocks with uninformative cues (dashed lines), 100% SP blocks (thick lines), and 100% DP blocks (thin lines). The shaded area indicates the N2pc measurement window

Analyses of ERP mean amplitudes in the N2pc time window (220-280 ms after cue onset) were conducted separately for blocks with spatially uninformative and informative cues. In blocks with uninformative cues, a main effect of laterality, F(1, 15) = 23.47, p < 0.01, reflecting the presence of an N2pc, was accompanied by an interaction between laterality and cue color, F(1, 15) = 6.89, p < 0.05, as the N2pc was much larger in response to matching as compared to non-matching cues. Follow-up analyses revealed that a reliable N2pc was triggered not just by matching cues, t(15) = 4.37, p < 0.01, but by non-matching cues as well, t(15) = 2.50, p < 0.05. The N2pc analysis for spatially informative cues contained the additional variable of cue-target position (100% SP blocks vs. 100% DP blocks). A main effect of laterality, F(1, 15) = 30.05, p < 0.01, confirmed the presence of an N2pc with informative cues. Critically, this component was much larger when these cues matched the current target color than for non-matching cues, and this effect of top-down task set for color was reflected by a highly significant laterality × cue color interaction, F(1, 15) = 17.02, p < 0.01. There was also a tendency toward an interaction between laterality and cue-target position, F(1, 15) = 3.62, p = 0.08, with numerically larger N2pc components in 100% SP blocks than in 100% DP blocks. The three-way interaction between these factors was far from significant (laterality × cue color × cue-target position: F < 1.00). Analyses conducted separately for matching and non-matching cues in 100% SP and 100% DP blocks found that an N2pc was reliably present for matching cues in both types of blocks, both ts(15) > 5.40, both ps < 0.01. For non-matching cues, a significant N2pc was observed in 100% SP blocks, t(15) = 2.13, p = 0.05, but not in 100% DP blocks, t(15) = 1.28, p = 0.22.

To further confirm the observation that top-down color task set modulated the N2pc to color singleton cues regardless of whether these cues were spatially informative or not, an omnibus ANOVA was conducted across blocks with informative and uninformative cues, which now included the new three-level variable cue validity (uninformative, 100% SP, 100% DP). A main effect of laterality, F(1, 15) = 29.52, p < 0.01, was accompanied by a laterality × cue color interaction, F(1, 15) = 14.77, p < 0.01, again confirming that the N2pc to color singleton cues was modulated by the current top-down task set for color. Critically, there was no indication of any three-way interaction between laterality, cue color, and cue validity (F < 1.00), demonstrating that this modulation of the N2pc by top-down task set was triggered in an equivalent fashion in blocks with spatially uninformative cues, in 100% SP blocks, and in 100% DP blocks.

The difference waveforms in Fig. 4 strongly suggest that the initial phase of the N2pc in response to color singleton cues was exclusively modulated by whether these cues matched the current top-down color task set, but was unaffected by their spatial informativeness. In contrast, both factors seem to have had an effect on the later phase of the N2pc. To substantiate this observation, the N2pc time window was divided into two successive 30-ms intervals (220-250 and 250-280 ms, respectively) that represent the early and late part of the N2pc, and separate analyses were conducted on ERP mean amplitudes obtained within both intervals. These analyses included all three blocked cue validity conditions (uninformative, 100% SP, 100% DP). In the early time window (220-250 ms), a main effect of laterality, F(1, 15) = 25.13, p < 0.01, was accompanied by a laterality × cue color interaction, F(1, 15) = 12.65, p < 0.01, reflecting larger N2pc components for matching as compared to non-matching cues. The N2pc triggered by matching cues was highly significant, t(15) = 4.60, p < 0.01, whereas the N2pc to non-matching cues only approached significance, t(15) = 2.00, p = 0.06. Most importantly, there was no laterality × cue validity interaction for this early time window (F < 1), demonstrating that the spatial information about target positions that was provided by color singleton cues had no impact whatsoever on the early phase of the N2pc. There was also no three-way interaction between laterality, cue color, and cue validity (F < 1.00).

During the later phase of the N2pc (250-280 ms after cue onset), a main effect of laterality, F(1, 15) = 27.41, p < 0.01, was again accompanied by a laterality × cue color interaction, F(1, 15) = 12.55, p < 0.01, confirming that top-down color task set continued to have a strong modulatory effect on the N2pc. A reliable N2pc was observed not just for matching cues, t(15) = 5.94, p < 0.01, but also for non-matching cues, t(15) = 2.25, p < 0.05. In contrast to the early phase of the N2pc, there was now a laterality × cue validity interaction, F(2, 30) = 3.53, p < 0.05, suggesting that at this later point in time, the N2pc was also affected by the spatial informativeness of cues. As can be seen from the difference waveforms in Fig. 4, the late phase of the N2pc was largest in blocks with 100% SP cues, intermediate in blocks with uninformative cues, and smallest in blocks with 100% DP cues. Follow-up analyses conducted separately for combinations of two cue validity conditions confirmed that the late phase of the N2pc was reliably larger in 100% SP blocks than in 100% DP blocks, F(1, 15) = 6.96, p < 0.05. N2pc amplitudes in blocks with uninformative cues did not differ significantly from 100% SP or 100% DP blocks (both Fs < 2.40, both ps > 0.14). Interestingly, these cue validity effects on the late phase of the N2pc were very similar for target-color matching and for non-matching cues (see Fig. 4). The absence of a three-way interaction among laterality, cue color, and cue validity (F < 1.00) confirmed that the effects of top-down color task set and of the spatial information provided by the cues on the late phase of the N2pc were triggered in a parallel and independent fashion.

Discussion

Salient but spatially uninformative visual singleton cues trigger behavioral spatial cueing effects and an N2pc component only when they match current target features (e.g., Eimer & Kiss, 2008; Folk et al., 1992). This fact has been interpreted as evidence for task-set contingent involuntary attentional capture, but might alternatively reflect differences in the speed of top-down controlled attentional disengagement from stimuli with target-matching and non-matching features (Theeuwes, 2010). To find out which account is correct, we manipulated the validity of spatial information provided by task-set matching and non-matching color singleton cues. In some blocks, cues were spatially uninformative. In others, participants knew that targets would always appear at the cued location, and in a third type of blocks, cues and targets always appeared at diagonally opposite positions. This difference between 100% SP and 100% DP blocks should strongly discourage or encourage top-down controlled attentional disengagement from the cue stimuli, but should have little if any impact on contingent involuntary attentional capture.

In blocks with uninformative cues, behavioral and ERP results confirmed previous findings in support of task-set contingent attentional capture. Reliable behavioral spatial cueing effects were found for target-color matching cues, but not for non-matching cues, and the N2pc observed for matching cues was much larger than the N2pc to non-matching cues. While these observations are in line with previous ERP investigations of contingent attentional capture (e.g., Eimer & Kiss, 2008; Eimer et al., 2009; Lien et al., 2008), it should be noted that in contrast to these earlier studies, the N2pc to spatially uninformative non-matching cues was statistically reliable, suggesting that some residual attentional capture was triggered by these cues. This may be a consequence of the design of the current experiment. In two thirds of all blocks, cues provided spatial information about the location of the target, thus encouraging the attentional processing of cues regardless of whether they matched the current task set. The transfer of an attentional set for cue selection from blocks where these cues provided spatial information to blocks with uninformative cues might be responsible for a strongly reduced but still reliable N2pc to spatially uninformative non-matching cues. In line with this interpretation, N2pc mean amplitudes to these cues were numerically larger for those participants who started with one of the informative cue conditions (−0.61 μV) than for participants who started the experiment with uninformative cue blocks (−0.32 μV).

The results observed in 100% SP and 100% DP blocks provide clear evidence in favor of contingent involuntary attentional capture and against the differential disengagement account. In 100% SP blocks, participants had no reason to withdraw attention from either matching or non-matching cues. In 100% DP blocks, they had every incentive to rapidly disengage attention from these cues. If behavioral and ERP differences between matching and non-matching singleton cues observed in previous studies were due to the top-down controlled disengagement of attention from non-matching cues, such differences should be largely absent in these blocks. There should be little if any behavioral evidence for color-contingent attentional capture. For both types of cues, an N2pc of similar size should be triggered in 100% SP blocks, while no N2pc should be found in 100% DP blocks. In fact, a very different pattern of results was obtained. RTs were generally much faster in 100% SP relative to 100% DP blocks, which strongly suggests that participants maintained their attentional focus at the cued location in 100% SP blocks, but disengaged and redeployed attention at the opposite side in 100% DP blocks. In spite of this difference in top-down controlled attentional strategy associated with cue validity, there was still a strong impact of color task set, as the RT benefit for 100% SP relative to 100% DP blocks was substantially larger with matching than with non-matching cues (see Fig. 2). In other words, attentional capture by these cues was still strongly affected by their match with the current target-defining color (see also Folk et al., 1992, Experiments 1 and 2, for similar observations). This behavioral effect of color-contingent attentional capture was accompanied by marked N2pc differences between matching and non-matching cues. In both 100% SP and 100% DP blocks, much larger N2pc components were triggered by matching relative to non-matching cues.

While the onset phase of the N2pc (220-250 ms after cue onset) was solely modulated by cue color, but not by the difference between 100% SP and 100% DP blocks, the spatial information provided by the cues did affect the later phase of the N2pc (250-280 ms after cue onset), where amplitudes were larger in 100% SP blocks relative to 100% DP blocks (Fig. 4). This demonstrates that differences in top-down attentional disengagement strategies between these two types of blocks are reflected by the N2pc component, albeit at a later stage than color-contingent differences in attentional capture. It is notable that even during this later phase of the N2pc, a strong modulatory effect of color task set remained, with larger N2pc amplitudes to matching than non-matching cues. This effect did not interact with the effects of cue validity, suggesting that cue color and cue validity affected attentional mechanisms in a parallel and independent fashion.

The ERP results obtained in the 100% SP and 100% DP blocks demonstrate that color-contingent attentional capture by singleton cues preceded any strategic modulations of attentional processing that were associated with the spatial information that these cues provided. This is entirely in line with the contingent involuntary attentional capture hypothesis proposed by Folk et al. (1992), but not with the claim that contingent capture effects are the result of top-down controlled attentional disengagement from salient visual stimuli that do not match current task settings. Theeuwes (2010) argued that attentional selection is initially driven exclusively by bottom-up salience and that attentional control settings only affect subsequent post-selective processes such as attentional disengagement that are under full top-down control. The current results demonstrate that the initial stage of attentional selectivity is already strongly modulated by whether or not a color singleton cue matches the current task set, whereas the strategic top-down control of attentional disengagement only emerges at a later point in time.

A comparison of behavioral performance in blocks with informative and uninformative cues can yield useful insights into the attentional allocation strategy adopted when cues were spatially uninformative. RTs to targets at cued locations were faster in 100% SP blocks relative to blocks with uninformative cues (Fig. 2), demonstrating that participants were much more likely to maintain attention at the cued location in the former blocks. In contrast, similar RTs to targets at uncued locations were observed with uninformative cues and in 100% DP blocks, which indicates a similar degree of attentional disengagement in these two types of blocks. This is hardly surprising, as targets appeared at uncued locations on 75% of all trials in uninformative cue blocks, and participants therefore had a strong incentive to disengage attention from cued locations. As attention was actively maintained at cued locations in 100% SP blocks, but disengaged from these locations in 100% DP and uninformative cue blocks, the presence of virtually identical color-contingent spatial cueing effects on RT in all three types of blocks underlines the conclusion that these effects cannot be accounted for by differences in top-down attentional deallocation strategies.

One might argue that results obtained with spatially informative cues should not be used to draw inferences about mechanisms of involuntary attentional capture, because these cues elicit voluntary endogenous shifts of attention that are qualitatively distinct from the processes involved in involuntary capture. For example, the incentive to localize and process informative cues might result in a slower and more controlled search mode in which attentional capture is reduced (Theeuwes, 2010). However, the N2pc results obtained in the present study provide no evidence for any delay of attentional capture triggered by informative as compared to uninformative cues (Fig. 4). Furthermore, equivalent color-contingent behavioral spatial cueing effects were found in blocks with informative and uninformative cues. Both observations suggest that there were no qualitative differences in task-set contingent attentional capture triggered by spatially informative and uninformative singleton cues. More generally, a manipulation of top-down attention is obviously required in an experiment designed to find out whether task-set contingent spatial cueing effects reflect top-down attentional control or contingent involuntary attentional capture.

The current findings also have implications for our understanding of the link between the N2pc component and attentional capture. It has been claimed that the N2pc does not reflect the initial attentional selection of visual objects, but is instead associated with the analysis of task-relevant visual features at a later post-selection stage of processing (Theeuwes, 2010). According to this view, the N2pc is absent in response to salient singleton stimuli that do not match the current task set (Eimer & Kiss, 2008; Eimer et al., 2009; Lien et al., 2008) because the rapid disengagement of attention from such stimuli prevents this type of in-depth analysis. The present results cast serious doubt on this interpretation of the N2pc. While the presence or absence of top-down controlled attentional disengagement did indeed affect the later phase of the N2pc, encouraging rapid disengagement in 100% DP blocks clearly did not abolish the N2pc component. In fact, the early phase of the N2pc in these blocks was identical to the N2pc in 100% SP blocks, where attention remained focused at the cued location, which strongly suggests that this component is primarily associated with the rapid attentional selection of visual objects, rather than with later post-selective attentional processing. This conclusion is also supported by the results of a previous ERP study (Mazza et al., 2007), where the N2pc to color singleton targets was measured in blocks where observers simply had to report the side of this singleton, and in blocks where they had to make a much more difficult shape discrimination. Even though in-depth feature processing was necessary in the latter case, whereas only the selection of target location was required in the former case, N2pc components were identical in both types of tasks, in line with the hypothesis that this component does reflect the initial spatial selection of visual target objects that precedes their subsequent in-depth analysis.

One could in principle still argue that the N2pc does not reflect the initial capture of attention that is purely salience-driven and that the color-contingent N2pc effects observed in the present study are due to an almost instantaneous disengagement of attention from non-matching cues that precedes any strategic effects linked to cue validity. This is not only a complex scenario, according to which attention is first captured, then disengaged, and finally strategically re-deployed in 100% SP blocks, all within 200 ms after cue onset. It is also a scenario that would cast serious doubts on the presumed status of attentional disengagement as a top-down phenomenon because it regards disengagement from non-matching cues as unavoidable, regardless of participants’ selection intentions. More generally, the question may be raised whether ‘rapid capture followed by instantaneous disengagement’ is a useful scientific hypothesis that can be experimentally distinguished from ‘no capture at all’ (see Eimer & Kiss, 2010b, for further discussion).

In summary, the current findings demonstrate that feature-specific task sets have a strong impact on the rapid selection of salient visual objects. Attentional capture by these objects is not primarily determined by bottom-up salience, but by whether or not they match a currently active setting for target features. This task-set contingent attentional capture is rapid and involuntary, and precedes subsequent strategic mechanisms such as the active disengagement of attention.

References

Ansorge, U., Kiss, M., & Eimer, M. (2009). Goal-driven attentional capture by invisible colors: Evidence from event-related potentials. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 16, 648–653.

Belopolsky, A. V., Schreij, D., & Theeuwes, J. (2010). What is top-down about contingent capture? Attention. Perception & Psychophysics, 72, 326–341.

Bergen, J. R., & Julesz, B. (1983). Parallel vs. serial processing in rapid pattern discrimination. Nature, 303, 696–698.

Bichot, N. P., Rossi, A. F., & Desimone, R. (2005). Parallel and serial neural mechanisms for visual search in macaque area V4. Science, 308, 529–534.

Eimer, M. (1996). The N2pc component as an indicator of attentional selectivity. Electroencephalography and Clinical Neurophysiology, 99, 225–234.

Eimer, M., & Kiss, M. (2008). Involuntary attentional capture is determined by task set: Evidence from event-related brain potentials. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 20, 1423–1433.

Eimer, M., & Kiss, M. (2010a). Top-down search strategies determine attentional capture in visual search: Behavioral and electrophysiological evidence. Attention. Perception, & Psychophysics, 72, 951–962.

Eimer, M., & Kiss, M. (2010b). The top-down control of visual selection and how it is linked to the N2pc component – A reply to Theeuwes (2010). Acta Psychologica, 135, 100–102.

Eimer, M., Kiss, M., Press, C., & Sauter, D. (2009). The roles of feature-specific task set and bottom-up salience in attentional capture: An ERP study. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 35, 1316–1328.

Folk, C. L., & Remington, R. W. (1998). Selectivity in distraction by irrelevant featural singletons: Evidence for two forms of attentional capture. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 24, 847–858.

Folk, C. L., Remington, R. W., & Johnston, J. C. (1992). Involuntary covert orienting is contingent on attentional control settings. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 18, 1030–1044.

Folk, C. L., Remington, R. W., & Wright, J. H. (1994). The structure of attentional control: Contingent attentional capture by apparent motion, abrupt onset, and color. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 20, 317–329.

Hickey, C., McDonald, J. J., & Theeuwes, J. (2006). Electrophysiological evidence of the capture of visual attention. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 18, 604–613.

Itti, L., & Koch, C. (2001). Computational modelling of visual attention. Nature Reviews. Neuroscience, 2, 4–11.

Jolicœur, P., Sessa, P., Dell’Acqua, R., & Robitaille, N. (2006). Attentional control and capture in the attentional blink paradigm: Evidence from human electrophysiology. European Journal of Cognitive Psychology, 18, 560–578.

Kiss, M., Jolicœur, P., Dell'Acqua, R., & Eimer, M. (2008). Attentional capture by visual singletons is mediated by top-down task set: New evidence from the N2pc component. Psychophysiology, 45, 1013–1024.

Lien, M.-C., Ruthruff, E., Goodin, Z., & Remington, R. W. (2008). Contingent attentional capture by top-down control settings: Converging evidence from event-related brain potentials. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 34, 509–530.

Luck, S. J., & Hillyard, S. A. (1994). Spatial filtering during visual search: Evidence from human electrophysiology. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 20, 1000–1014.

Mazza, V., Turatto, M., Umiltà, C., & Eimer, M. (2007). Attentional selection and identification of visual objects are reflected by distinct electrophysiological responses. Experimental Brain Research, 181, 531–536.

Theeuwes, J. (1992). Perceptual selectivity for color and form. Perception & Psychophysics, 51, 599–606.

Theeuwes, J. (2010). Top-down and bottom-up control of visual selection. Acta Psychologica.

Theeuwes, J., Atchley, P., & Kramer, A. F. (2000). On the time course of top-down and bottom-up control of visual attention. In S. Monsell & J. Driver (Eds.), Attention and performance XVIII (pp. 105–125). Cambridge: MIT Press.

Wykowska, A., & Schubö, A. (in press). Irrelevant singletons in visual search do not capture attention but can produce non-spatial filtering costs. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience.

Author Note

Supported by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft Grant An 353/2-1 to Ulrich Ansorge and by a BBSRC grant (UK) to Martin Eimer. The authors thank John McDonald, Jan Theeuwes, and Chip Folk for their comments. Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Ulrich Ansorge, Fakultät für Psychologie, Universität Wien, Liebiggasse 5, A-1010 Vienna, Austria. E-mail: ulrich.ansorge@univie.ac.at.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Ulrich Ansorge, Fakultät für Psychologie, Universität Wien, Austria; Institut für Kognitionswissenschaft, Universität Osnabrück, Germany; Birkbeck College, London, UK; Franziska Worschech, Institut für Kognitionswissenschaft, Universität Osnabrück, Germany; Birkbeck College, London, UK; Monika Kiss, Birkbeck College, London, UK; Martin Eimer, Birkbeck College, London, UK.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ansorge, U., Kiss, M., Worschech, F. et al. The initial stage of visual selection is controlled by top-down task set: new ERP evidence. Atten Percept Psychophys 73, 113–122 (2011). https://doi.org/10.3758/s13414-010-0008-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.3758/s13414-010-0008-3