Gender Differences in Suicide Prevention Responses: Implications for Adolescents Based on an Illustrative Review of the Literature

Abstract

:1. Introduction

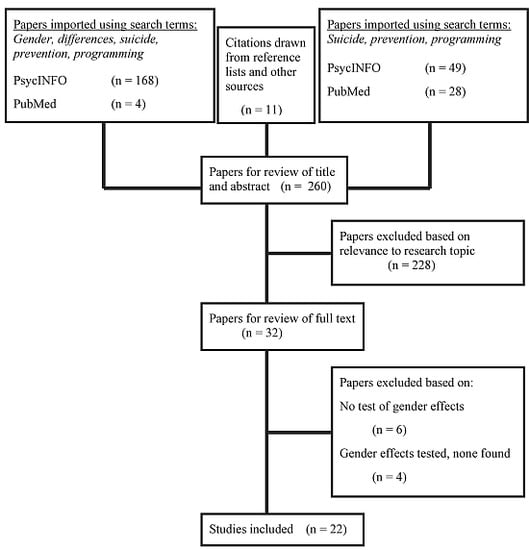

2. Method

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. School-Based Prevention Programming

3.1.1. Curricula

3.1.2. Gatekeepers

3.1.3. Screening

3.2. Community-Based Prevention Programming

3.2.1. PSA and Media Campaigns

3.2.2. Crisis Centers/Hotlines

3.3. Health-Based Prevention Programming

3.4. Discussion

3.4.1. Implications for Suicide Prevention in Adolescents

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kann, L.; Kinchen, S.; Shanklin, S.L.; Flint, K.H.; Hawkins, J.; Harris, W.A.; Lowry, R.; O’Malley Olsen, E.; McManus, T.; Chyen, D.; et al. Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance—United States, 2013; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC): Atlanta, GA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Preventing Suicide: A Global Imperative; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Crosby, A.E.; Ortega, L.; Melanson, C. Self-directed Violence Surveillance: Uniform Definitions and Recommended Data Elements, Version 1.0; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), National Center for Injury Prevention and Control: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Parks, S.E.; Johnson, L.L.; McDaniel, D.D.; Gladden, M. Surveillance for Violent Deaths—National Violent Death Reporting System, 16 States, 2010; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), National Center for Injury Prevention and Control: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Gould, M.S.; Kramer, R.A. Youth suicide prevention. Suicide Life Threat. Behav. 2001, 31, 6–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gould, M.S.; Velting, D.; Kleinman, M.; Lucas, C.; Thomas, J.G.; Chung, M. Teenagers’ attitudes about coping strategies and help-seeking behavior for suicidality. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2004, 43, 1124–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sullivan, E.; Annest, J.L.; Luo, F.; Simon, T.R.; Dahlberg, L.L. Suicide Among Adults Aged 35–64 Years—United States, 1999–2010; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Weisz, J.R.; Sandler, I.N.; Durlak, J.A.; Anton, B.S. Promoting and protecting youth mental health through evidence-based prevention and treatment. Am. Psychol. 2005, 60, 628–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mann, J.J.; Apter, A.; Bertolote, J.; Beautrais, A.; Currier, D.; Haas, A.; Hegerl, U.; Lonnqvist, J.; Malone, K.; Marusic, A.; et al. Suicide prevention strategies: A systematic review. JAMA 2005, 294, 2064–2074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klimes-Dougan, B.; Klingbeil, D.A.; Meller, S. The impact of universal suicide programs on youths’ help-seeking attitudes and behaviors. Crisis 2013, 34, 82–97. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bean, G.; Baber, K.M. Connect: An effective community-based youth suicide prevention program. Suicide Life Threat. Behav. 2011, 41, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cross, W.; Matthieu, M.M.; Cerel, J.; Knox, K.L. Proximate outcomes of gatekeeper training for suicide prevention in the workplace. Suicide Life-Threat. Behav. 2007, 37, 659–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freedenthal, S. Adolescent help-seeking and the Yellow Ribbon Suicide Prevention Program: An evaluation. Suicide Life Threat. Behav. 2011, 40, 628–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horowitz, L.M.; Wang, P.S.; Koocher, G.P.; Burr, B.H.; Smith, M.F.; Klavon, S.; Cleary, P.D. Detecting suicide risk in a pediatric emergency department: Development of a brief screening tool. Pediatrics 2001, 107, 1133–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Motto, J.A. Evaluation of a suicide prevention center by sampling the population at risk. Suicide Life Threat. Behav. 1971, 1, 18–22. [Google Scholar]

- Shim, R.S.; Compton, M.T. Pilot testing and preliminary evaluation of a suicide prevention education program for emergency department personnel. Community Ment. Health J. 2009, 46, 585–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciffone, J. Suicide prevention: An analysis and replication of a curriculum-based high school program. Soc. Work 2007, 52, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kataoka, S.; Stein, B.D.; Nadeem, E.; Wong, M. Who gets care? Mental health service use following a school-based suicide prevention program. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2007, 24, 1341–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, R.J.; Spilsbury, J.C.; Osiecki, S.S.; Denihan, W.M.; Zureick, J.L.; Friedman, S. Brief report: Preliminary results of a suicide awareness mass media campaign in Cuyahoga County, Ohio. Suicide Life Threat. Behav. 2008, 38, 245–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfaff, J.J.; Acres, J.G.; McKelvey, R.S. Training general practitioners to recognise and respond to psychological distress and suicidal ideation in young people. Med. J. Aust. 2001, 174, 222–226. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Carter, G.L.; Clover, K.; Whyte, I.M.; Dawson, A.H.; D’Este, C. Postcards from the EDge project: Randomised controlled trial of an intervention using postcards to reduce repetition of hospital treated deliberate self poisoning. BMJ 2005, 331, 805–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaffer, D.; Scott, M.; Wilcox, H.; Maslow, C.; Hicks, R.; Lucas, C.P.; Garfinkel, R.; Greenwald, S. The Columbia suicidescreen: Validity and reliability of a screen for youth suicide and depression. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2004, 43, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaffer, D.; Vieland, V.; Garland, A.; Rojas, M.; Underwood, M.M.; Busner, C. Adolescent suicide attempters. Response to suicide-prevention programs. JAMA 1990, 264, 3151–3155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eckert, T.L.; Miller, D.N.; Riley-Tillman, T.C.; DuPaul, G.J. Adolescent suicide prevention: Gender differences in students’ perceptions of the acceptability and intrusiveness of school-based screening programs. J. Sch. Psychol. 2006, 44, 271–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spirito, A.; Overholser, J.; Ashworth, S.; Morgan, J.; Benedict-Drew, C. Evaluation of a suicide awareness curriculum for high school students. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 1988, 27, 705–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalafat, J.; Elias, M. An evaluation of a school-based suicide awareness intervention. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 1994, 24, 224–233. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kalafat, J.; Gagliano, C. The use of simulations to assess the impact of an adolescent suicide response curriculum. Suicide Life Threat. Behav. 1996, 26, 359–364. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Overholser, J.C.; Hemstreet, A.C.; Spirito, A.; Vyse, S. Suicide awareness programs in the schools: Effects of gender and personal experience. J. Am. Acad. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 1989, 28, 925–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aseltine, R.; DeMartino, R. An outcome evaluation of the SOS suicide prevention program. Am. J. Public Health 2004, 94, 446–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aseltine, R.; James, A.; Schilling, E.A.; Glanovsky, J. Evaluating the SOS suicide prevention program: A replication and extension. BMC Public Health 2007, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciffone, J. Suicide prevention: A classroom presentation to adolescents. Soc. Work 1993, 38, 197–203. [Google Scholar]

- Garlow, S.J.; Rosenberg, J.; Moore, J.D.; Haas, A.P.; Koestner, B.; Hendin, H.; Nemeroff, C.B. Depression, desperation, and suicidal ideation in college students: Results from the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention College Screening Project at Emory University. Depress. Anxiety 2008, 25, 482–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klimes-Dougan, B.; Lee, C.-Y.S.; Houri, A.K. Suicide prevention with adolescents: Considering potential benefits and untoward effects of public service announcements. Crisis 2009, 30, 128–135. [Google Scholar]

- Daigle, M.; Beausoleil, L.; Brisoux, J.; Raymond, S.; Charbonneau, L.; Desaulniers, J. Reaching suicidal people with media campaigns. Crisis 2006, 27, 172–180. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wright, N.; Klimes-Dougan, B. Personalized suicide prevention. Unpublished work.

- Medoff, M.H. An evaluation of the effectiveness of suicide prevention centers. J. Behav. Econ. 1986, 3, 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, H.L.; Coombs, D.W.; Leeper, J.D.; Barton, S.N. An analysis of the effects of suicide prevention facilities on suicide prevention rates in the United States. Am. J. Public Health 1984, 74, 340–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haller, D.M.; Sanci, L.A.; Sawyer, S.M.; Patton, G.C. The identification of young people’s emotional distress: A study in primary care. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2009, 59, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, D.G. Depression screening as an intervention against suicide. J. Clin. Psychiarity 1999, 60, 42–45. [Google Scholar]

- Verbrugge, L.M. How physicians treat mentally distressed men and women. Soc. Sci. Med. 1984, 18, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rutz, W.; von Knorring, L.; Wålinder, J. Long-term effects of an educational program for general practitioners given by the Swedish Committee for the Prevention and Treatment of Depression. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 1992, 85, 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carter, G.L.; Clover, K.; Whyte, I.M.; Dawson, A.H.; D’Este, C. Postcards from the EDge: 24-Month outcomes of a randomised controlled trial for hospital-treated self-poisoning. Br. J. Psychiatry 2007, 191, 548–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gould, M.S.; Greenberg, T.; Velting, D.; Shaffer, D. Youth suicide risk and preventive interventions: A review of the past 10 years. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2003, 42, 386–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaffer, D.; Garland, A.; Gould, M.; Fisher, P.; Trautman, P. Preventing teenage suicide: A critical review. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 1988, 27, 675–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wyman, P.A.; Brown, C.H.; Inman, J.; Cross, W.; Schmeelk-Cone, K.; Guo, J.; Peña, J.B. Randomized trial of a gatekeeper program for suicide prevention: 1-Year impact on secondary school staff. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2008, 76, 104–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaffer, D.; Craft, L. Methods of adolescent suicide prevention. J. Clin. Psychiatry 1999, 60, 70–74. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ashford, E. The fight over screening students to prevent suicide. Educ. Dig. 2005, 71, 52–56. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, D.N.; Eckert, T.L.; DuPaul, G.J.; White, G.P. Adolescent suicide prevention: Acceptability of school-based programs among secondary school principals. Suicide Life Threat. Behav. 1999, 29, 72–85. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Niederkrotenthaler, T.; Voracek, M.; Herberth, A.; Till, B.; Strauss, M.; Etzersdorfer, E.; Eisenwort, B.; Sonneck, G. Role of media reports in completed and prevented suicide: Werther v. Papageno effects. Br. J. Psychiatry 2010, 197, 234–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lester, D. The effectiveness of suicide prevention centers: A review. Suicide Life Threat. Behav. 1997, 27, 304–310. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Luoma, J.B.; Martin, C.E.; Pearson, J.L. Contact with mental health and primary care providers before suicide: A review of the evidence. Am. J. Psychiarty 2002, 159, 909–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutz, W.; von Knorring, L.; Pihlgren, H.; Rihmer, Z.; Wålinder, J. Prevention of male suicides: Lessons from Gotland study. Lancet 1995, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rihmer, Z.; Rutz, W.; Pihlgren, H. Depression and suicide on Gotland an intensive study of all suicides before and after a depression-training program for general practitioners. J. Affect. Disord. 1995, 35, 147–152. [Google Scholar]

- Wålinder, J.; Rutz, W. Male depression and suicide. Int. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2001, 16, S21–S24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berman, A.L.; Jobes, D.A. Suicide prevention in adolescents (ages 12–18). Suicide Life Threat. Behav. 1995, 25, 143–154. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Copeland, E.; Hess, R. Differences in young adolescents’ coping strategies based on gender and ethnicity. J. Early Adolesc. 1995, 15, 203–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schonert-Reichl, K.A.; Muller, J.R. Correlates of help-seeking in adolescence. J. Youth Adolesc. 1996, 25, 705–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canetto, S.S. Meanings of gender and suicidal behavior during adolescence. Suicide Life Threat. Behav. 1997, 27, 339–351. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rickwood, D.J.; Deane, F.P.; Wilson, C.J. When and how do young people seek professional help for mental health problems? Med. J. Aust. 2007, 187, S35–S39. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Durkheim, E. Suicide: A Study in Sociology [1897]; The Free Press: Glencoe, IL, USA, 1951. [Google Scholar]

- Help-Seeking among Men: Implications for Suicide Prevention. Available online: http://www.suicidology.org/c/document_library/get_file?folderId=254&name=DLFE-439.pdf (accessed on 8 January 2015).

- Sierra Hernandez, C.A.; Oliffe, J.L.; Joyce, A.S.; Söchting, I.; Ogrodniczuk, J.S. Treatment preferences among men attending outpatient psychiatric services. J. Ment. Health 2014, 23, 83–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutierrez, L.M. Beyond coping: An empowerment perspective on stressful life events. J. Sociol. Soc. Welf. 1994, 21, 201–219. [Google Scholar]

- Chilvers, C.; Dewey, M.; Fielding, K.; Gretton, V.; Miller, P.; Palmer, B.; Weller, D.; Churchill, R.; Williams, I.; Harrison, G.; et al. Antidepressant drugs and generic counselling for treatment of major depression in primary care: Randomised trial with patient preference arms. BMJ 2001, 322, 772–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geers, A.L.; Rose, J.P.; Fowler, S.L.; Rasinski, H.M.; Brown, J.A.; Helfer, S.G. Why does choice enhance treatment effectiveness? Using placebo treatments to demonstrate the role of personal control. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2013, 105, 549–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, S.E.; Barber, J.P. Should treatment for depression be based more on patient preference? Patient Prefer. Adher. 2013, 7, 1047–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2015 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hamilton, E.; Klimes-Dougan, B. Gender Differences in Suicide Prevention Responses: Implications for Adolescents Based on an Illustrative Review of the Literature. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 2359-2372. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph120302359

Hamilton E, Klimes-Dougan B. Gender Differences in Suicide Prevention Responses: Implications for Adolescents Based on an Illustrative Review of the Literature. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2015; 12(3):2359-2372. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph120302359

Chicago/Turabian StyleHamilton, Emma, and Bonnie Klimes-Dougan. 2015. "Gender Differences in Suicide Prevention Responses: Implications for Adolescents Based on an Illustrative Review of the Literature" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 12, no. 3: 2359-2372. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph120302359