- 1Academic Medical Center (AMC), Amsterdam, Netherlands

- 2The Hague’s Public Health Department, The Hague, Netherlands

- 3Leiden University Medical Center, Leiden, Netherlands

- 4VU University Medical Center, Amsterdam, Netherlands

This article describes the development of the social network-based intervention Powerful Together with Diabetes which aims to improve diabetes self-management (DSM) among patients with type 2 diabetes living in socioeconomically deprived neighborhoods by stimulating social support for DSM and diminishing social influences hindering DSM (e.g., peer pressure and social norms). The intervention was specifically developed for patients with Dutch, Turkish, Moroccan, and Surinamese backgrounds. The intervention was developed according to Intervention Mapping. This article describes the first four steps of Intervention Mapping: (1) the needs assessment; (2) development of performance and change objectives; (3) selection of theory-based methods and strategies; and (4) the translation of these into an organized program. These four steps resulted in Powerful Together with Diabetes, a 10-month group-based intervention consisting of 24 meetings, 6 meetings for significant others, and 2 meetings for participants and their spouses. The IM method resulted in a tailored approach with a specific focus on the social networks of its participants. This article concludes that the IM method helped our planning team to tailor the intervention to the needs of our target population and facilitated our evaluation design. However, in hindsight, the intervention could have been improved by investing more in participatory planning and community involvement.

Introduction

People in lower socioeconomic groups, including ethnic minorities, are not only disproportionately affected by type 2 diabetes, they also have more diabetes-related complications and higher diabetes-related mortality compared with patients in higher socioeconomic groups (1–3). A recent study among ethnic minorities in the Netherlands shows that of those patients that were medically treated, only 37–53% had HbA1c levels on target (4). To the best of our knowledge, no comparable information on glycemic control in Dutch patients in lower socioeconomic groups in the Netherlands is known.

A poorer glycemic control, related to less adequate self-management behaviors, partly accounts for these increased risks (5). Properly managing type 2 diabetes requires a schedule of extensive self-management behaviors. These include an adequate use of medications, if applicable self-monitoring of blood glucose, eating healthy and being physical active, regularly checking and taking adequate care of the feet and dealing adequately with diabetes in every situation (6). Complying with and maintaining such complex health regimens seem to be challenging, especially for socioeconomically deprived patients (7–9).

Low incomes, a low educational level and living in a deprived neighborhood are associated with a lower prevalence of blood glucose monitoring and not knowing how to deal with extreme blood glucose levels (10, 11). Furthermore, especially the combination of smoking, physical inactivity and a lower consumption of fruit and vegetables is prevalent in socioeconomically deprived groups in the Netherlands (12–16). There is thus a need for effective interventions that improve glycemic control among socioeconomically deprived patients with type 2 diabetes.

There are multiple factors that influence self-management behaviors among socioeconomically deprived patients, such as a lack of knowledge, low health literacy, low risk perception, low outcome expectations, low self-efficacy, and specific socioeconomic barriers (lack of financial resources and environmental factors) (7, 9, 17–21). However, an increasing amount of studies shows that social interactions with friends and family members have a major impact on self-management behaviors as well.

Social support, the aid and assistance exchanged through social relationships and interpersonal transactions, can positively influence self-management, but significant others can also hinder self-management by interfering with or paying too much attention to self-management (22, 23). Socioeconomically deprived patients seem to have less access to supportive social networks, to generally have fewer sources of social support in their social environments and to receive less social support, which is needed for adherence (24–26). In addition, they are often confronted with social influences from their immediate social environments that hinder self-management (e.g., peer pressure, specific cultural beliefs and expectations, and fewer positive role models) (27, 28). Interventions that target social influences affecting self-management behavior, such as social support, might be promising. To the best of our knowledge, there are no interventions that focus simultaneously on social support and hindering social influences in this target population.

Therefore, we developed a social network-based intervention (Powerful Together with Diabetes) that aimed to stimulate social support for self-management and to diminish hindering social influences on diabetes self-management (DSM) among socioeconomically deprived patients. This target population often has poor reading and writing skills (20). Furthermore, using electronical devices and participating in online communities might be hindered by a low income and low health literacy (29, 30). Therefore, in our study design, we choose to focus on real-life social networks instead of focusing on online social networks.

We used IM to develop Powerful Together with Diabetes (31). The development was part of a 4-year project consisting of the development, implementation and evaluation of the intervention. We had 1 year for the intervention development and preparation for implementation. The study design, results of the process evaluation, and the effects of the intervention on outcome measures are described in a number of papers (32–34).

This article describes the first four steps of the intervention development. The development of the entire intervention is described in detail in the handbook and the materials, which are available from the author. The development of the most distinctive features of this intervention is outlined here including the specific focus on social support and social influences that affect self-management, particularly in patients from socioeconomically disadvantaged neighborhoods, and on examining the specific educational requirements of patients living in such neighborhoods.

Materials and Methods

The first four phases of Intervention Mapping consist of the following: (1) conducting a needs assessment, (2) creating performance and change objectives, (3) selecting theory-based intervention methods and practical strategies, and (4) translating methods and strategies in an appropriately organized program. This section describes the methods used for the needs assessment.

Needs Assessment

The needs assessment consisted of a literature review and a qualitative study. The most current version of the IM handbook specifically focuses on participatory planning (35). However, at the beginning of this project in the IM handbook of 2006, this focus was less extensive (31). We encountered some barriers to participatory planning as advocated by the IM method. For example, we did not know the exact neighborhoods in which the intervention would be implemented due to difficulties with the recruitment of general practitioners (GPs). We planned to aim the intervention at a very specific target population (with suboptimal glycemic control) and did not want to create false expectations within a community. Therefore, we did not precisely know which community to address. Because of these barriers combined with time constraints, we choose to focus more on other aspects of the intervention development instead of on participatory planning.

Literature Review

The needs assessment started with a scoping review of the literature (unpublished) on social support and an exploration of theories related to self-management: the theory of self-regulation, different self-management theories, and the transactional model of stress and coping, relapse prevention, and social learning theories (36–40). The databases PubMed, Embase, PsycINFO, and Google Scholar were searched for articles describing the influence of social support on diabetes outcomes and DSM. A search was also made for intervention studies that aimed to increase or create social support for DSM.

The literature review provided a general overview of the most important factors related to self-management of people with type 2 diabetes, i.e., low outcome expectations, low self-efficacy, lack of knowledge on diabetes, and low risk perception (7, 9, 17–21). The review also revealed that not only social support but also other social influences in the immediate social environments of the patients (e.g., peer pressure, social norms, and role models) are important for self-management, especially in patients from socioeconomically deprived neighborhoods.

However, information was lacking on the precise nature of these determinants among our target population. For example, which social norms and role models are present in the social environment of these patients and how do these affect self-management behaviors? What form does peer pressure take and how is this related to self-management behaviors? How can these determinants be influenced? With the aim to address these questions, we then conducted a qualitative study to further examine the relation between social support and other social determinants on self-management behaviors. This qualitative study was conducted among people with type 2 diabetes from socioeconomically deprived neighborhoods, particularly Turkish, Moroccan, Surinamese, and Dutch patients.

Qualitative Study

During this project, we had 1 year for the intervention development and the preparation for implementation (recruitment of GPs and patients, writing our proposal for the medical ethical committee). In practice, we had 4 months for our needs assessment.

The qualitative study consisted of semi-structured in-depth interviews with health-care professionals and their patients. In addition, participant observations took place and we analyzed a forum held for people with diabetes. Because of time constraints, we decided that 24 in-depth interviews would be attainable. To further validate our findings, we also re-analyzed the in-depth interviews and focus group discussions with people with diabetes that were organized and conducted by fellow researchers.

Interviews

Semi-structured in-depth interviews were held with people with diabetes from lower socioeconomic groups (n = 21) and their health-care professionals (n = 3). They were recruited via a diabetes nurse who was working in a socioeconomically deprived neighborhood and via an advertisement placed on a diabetes forum. All three health-care professionals (two diabetes nurses and one general practice assistant) worked in socioeconomically deprived neighborhoods and were recruited with the help of GPs involved in this study.

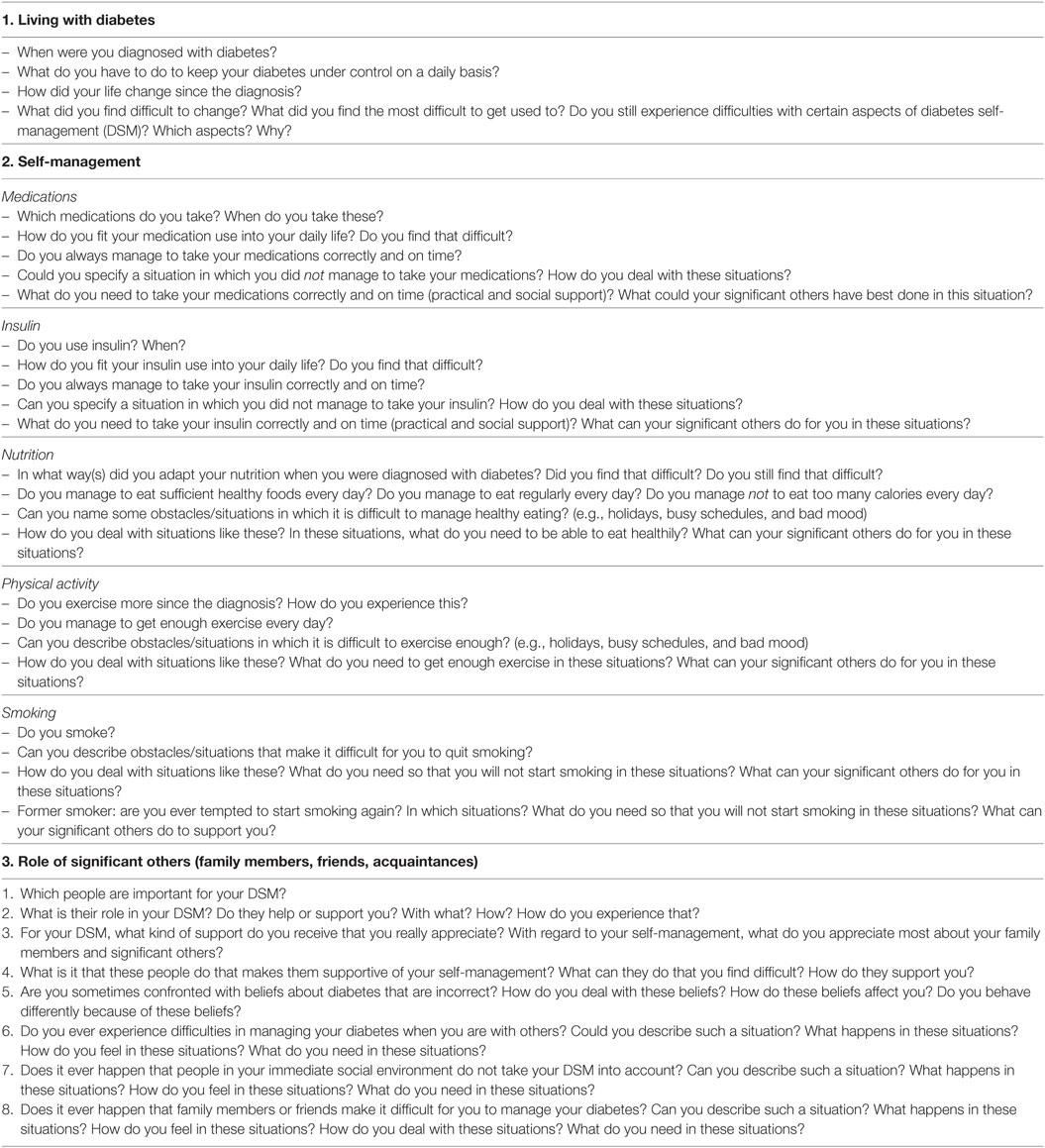

The 21 patient interviews were conducted at the respondents’ homes or, if preferred, at a local community center or health-care center (each interview lasted 60–90 min). For all interviews, a topic list was used which was revised in the light of emerging findings. Relevant topics (Table 1) included as follows: self-management in daily life, barriers and facilitators to self-management, interactions with health-care professionals, and the role of relatives/friends in self-management.

After patients had provided informed consent, the interviews were recorded, transcribed verbatim, and analyzed with MAXQDA software using framework analyses (41). In addition, a secondary analysis was performed on data from previous research (interviews and focus group discussions with people with diabetes from socioeconomically deprived neighborhoods). These interviews were held with Surinamese, Turkish, and Moroccan patients, as well as with patients from lower socioeconomic groups in general, and included topics similar to those used in our own interviews. Parts of these interviews were already coded in MAXQDA, which enabled us to incorporate the relevant codes into our own analyses; the remaining interviews were analyzed using framework analyses (21, 42–45).

Observations

The daily practice of a diabetes nurse working in a socioeconomically deprived neighborhood in The Hague was closely observed. Observations were also made during a 6-week intervention called “Dealing with Diabetes” that was organized for Turkish, Moroccan, and Dutch people with type 2 diabetes in socioeconomically deprived neighborhoods in Amsterdam. This took place by means of a participant, non-structured observation. One of our research group (Charlotte Vissenberg) observed all patient consultations with the diabetes nurse for 2 days from 0800 to 1700 hours in September 2008. The diabetes nurse saw (on average) 20 patients per day. The researcher sat in the nurse’s office (unobtrusively at the back) and was introduced to each patient as a colleague who would observe the consultations. All patients were asked if they had any questions regarding this observation; moreover, each patient was guaranteed his/her anonymity and was asked to provide informed consent. None of the patients had any questions and none refused participation. During the group-based intervention “Dealing with Diabetes,” the researcher (Charlotte Vissenberg) sat at the back of the room whilst the patients took part in the intervention.

During the observations, the researcher (Charlotte Vissenberg) wrote down everything that she saw and heard. After each consultation, she checked her findings with the diabetes nurse and the health promoter to ensure/optimize validity. These field notes were subsequently analyzed using thematic charting.

Analysis of Forums for People with Diabetes

Finally, we analyzed all the public content of forums held for people with diabetes. It appears that individuals (subjectively) report worse health and more often seek health information online, than individuals (subjectively) report good health. Furthermore, much information sought online is related to “sensitive” health topics that people prefer not to discuss with others (46). Kummervold et al. found that almost half of their respondents discussed personal problems online that they did not discuss with other people (47). Therefore, we analyzed all the public content of a forum organized for people with diabetes (48).

This forum was not specifically intended for patients from socioeconomically deprived neighborhoods and we doubted that these patients would participate in such a forum. However, we expected younger patients from our target population to participate, which might provide us with useful information as well. We selected www.diabetesforum.nl because it was organized by a professional organization (the National Diabetes Association), very active (lots of activity of members but also lots of new users) and was accessible to us.

Particular attention was paid to comments that indicated a lower socioeconomic background, e.g., related to educational level or profession, and to writing that included language that we recognized from our needs assessment phase.

We analyzed all public content from this forum from until April 2010. The content was analyzed using selective coding, focusing only on barriers/facilitators to self-management and the role of significant others (e.g., relatives and friends) in the performance of self-management. Additional analyses were performed using framework analysis (41).

Results

We start this section with a description of the intervention lay out (step 4 of IM) followed by an explanation how we came to this specific intervention lay out (steps 1–3 of IM: the results of the needs assessment, performance and change objectives, the intervention methods and strategies).

The Intervention Layout

This section describes the way the intervention was set up for the participants. Powerful together with Diabetes is a group intervention that lasted 10 months and consisted of the following 32 meetings: (i) 24 for participants (10 per group), (ii) 6 for their significant others, and (iii) 2 social network therapy sessions, which was attended by the participants and their significant others. These three components are described separately below.

Meetings for Participants

Phase 1

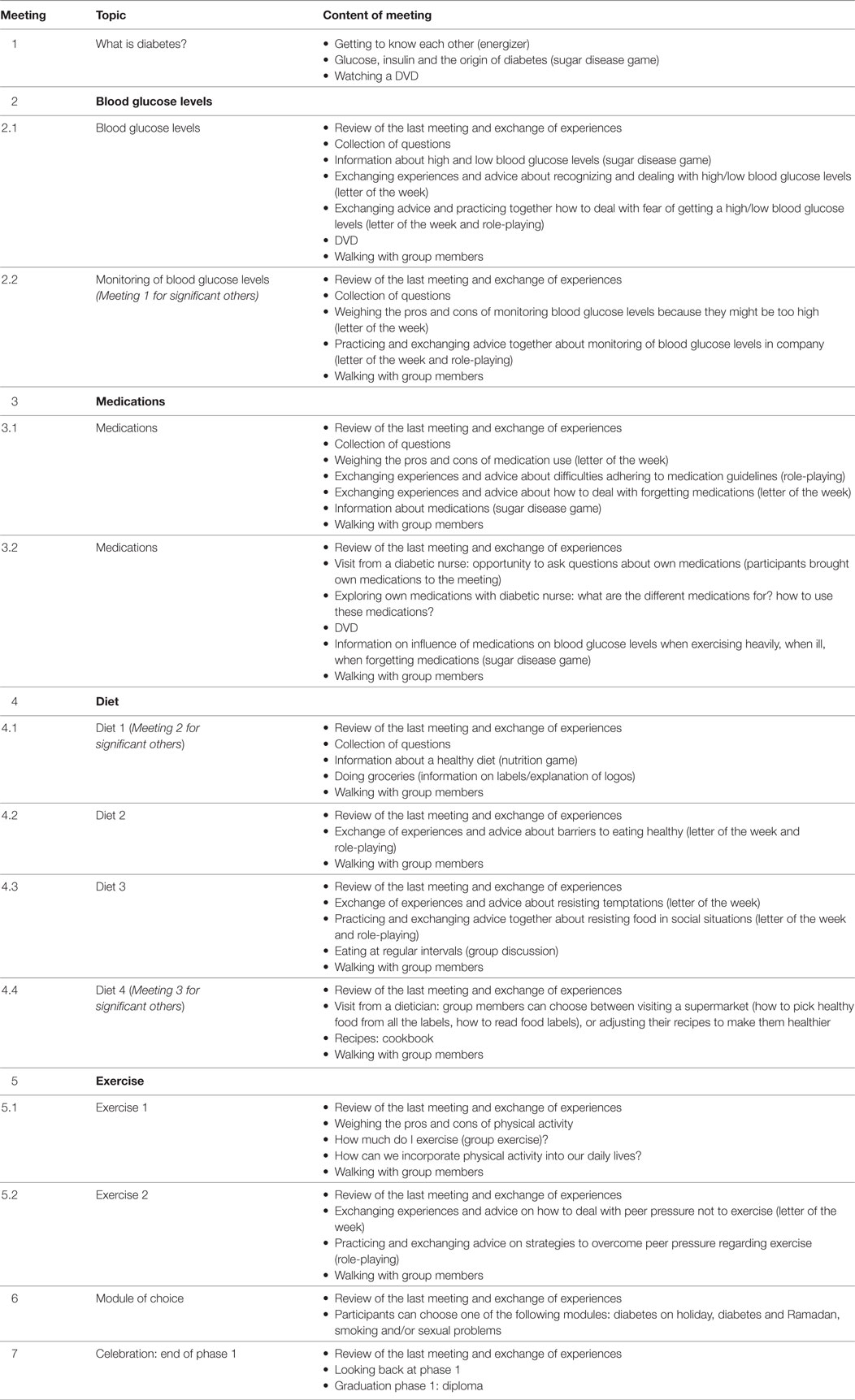

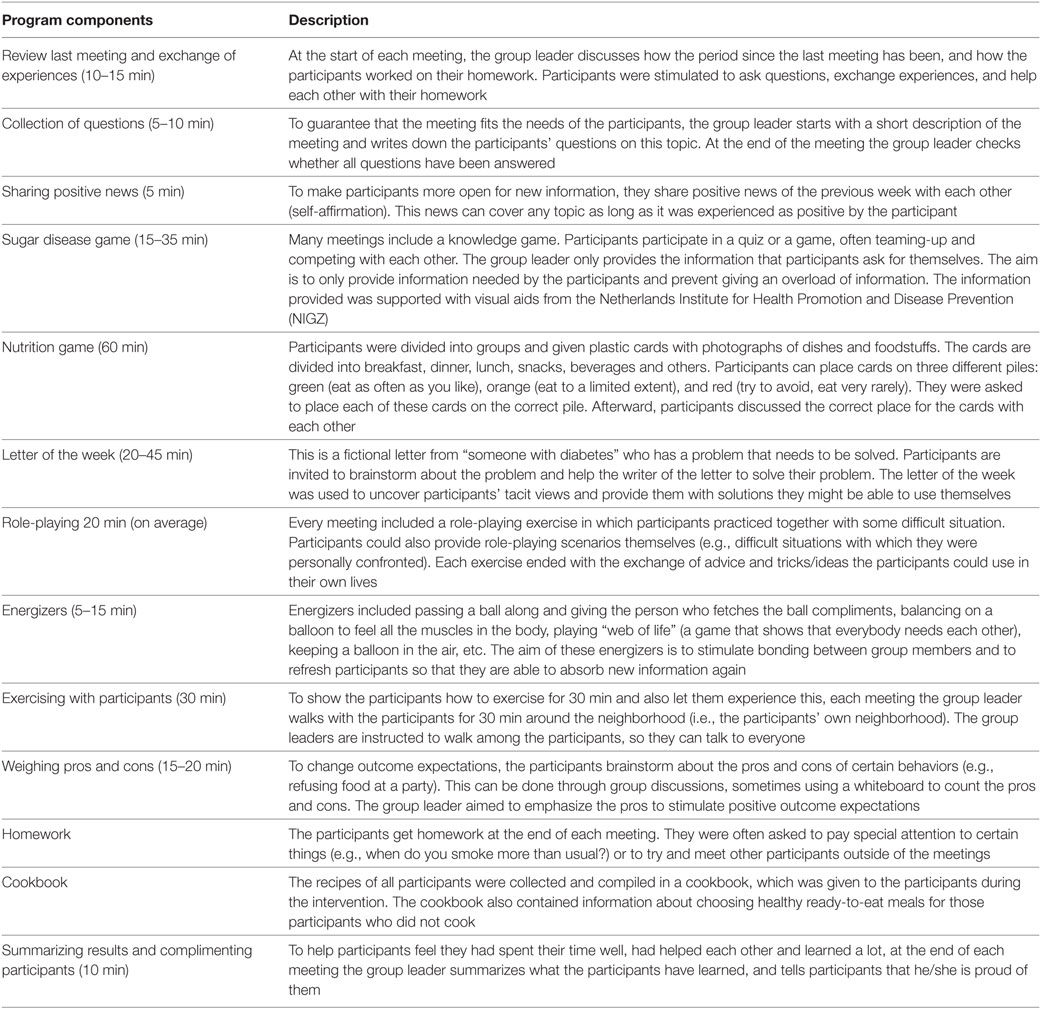

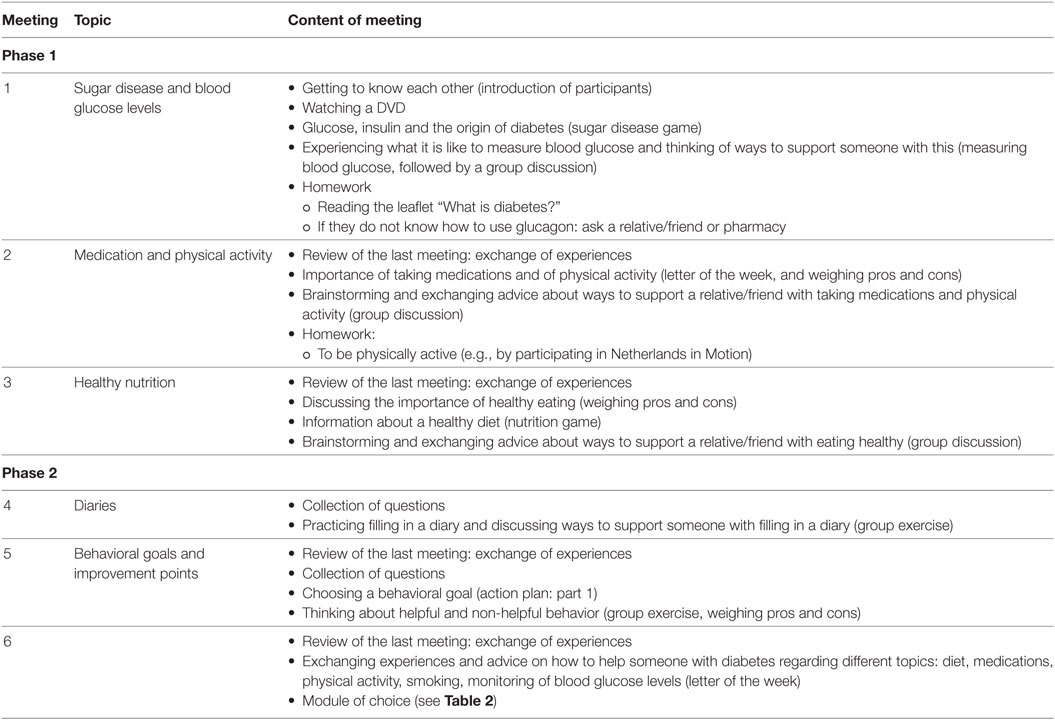

Phase 1 focused on providing the participants with the basic tools to manage their diabetes. During this phase that lasted 3 months, participants came together every week for 2 h in a community center (within walking distance from their homes) under the supervision of a group leader. During phase 1, five topic were discussed: what is diabetes (one meeting), blood glucose levels (two meetings), medications (two meetings), diet (four meetings), and exercise (two meetings). The last two meetings entailed a module of choice and the celebration of the end of phase 1. Each meeting centered around one topic and started with drinking coffee and tea followed by interactive games, quizzes, and role-playing exercises combined with energizers (fun exercises to stimulate bonding between participants and to provide a break for participants to increase the attention span). At the end of the meeting, the participants walked with each other around the neighborhood. Table 2 presents an overview of the topics.

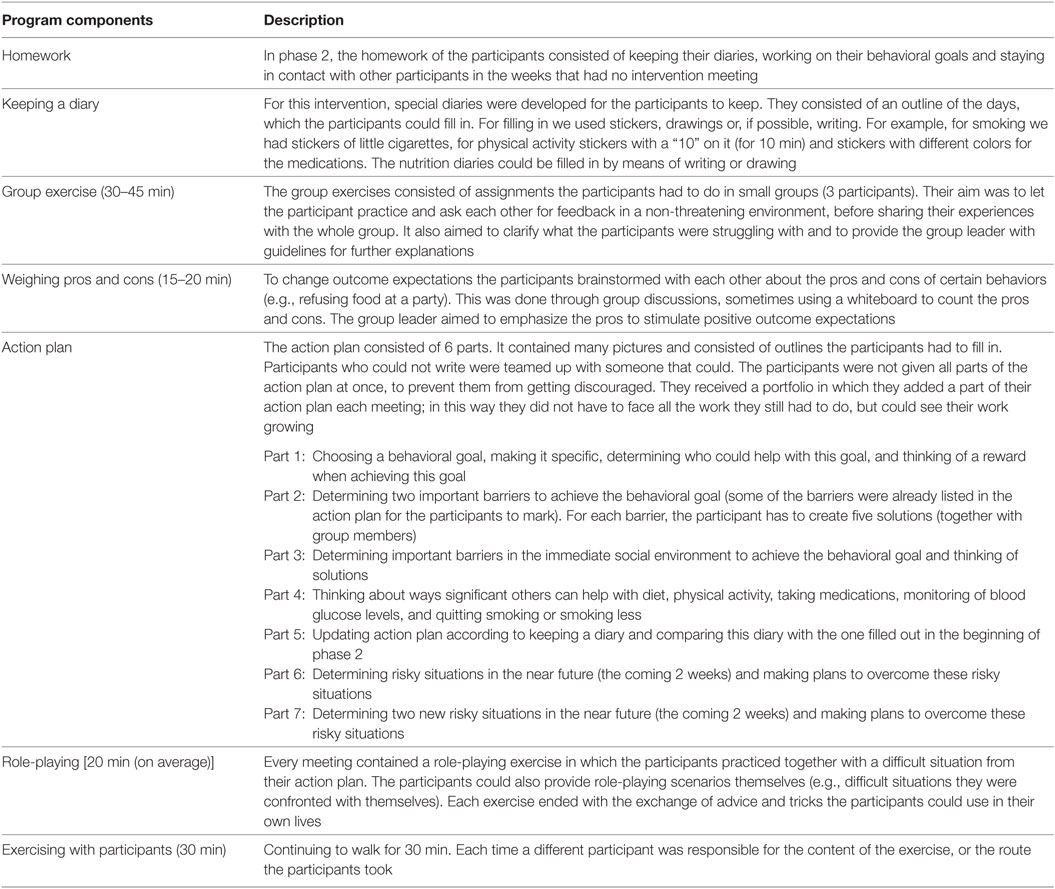

In phase 1, recurring program components were as follows: question time, sharing positive news, sugar disease game, nutrition game, letter of the week, role-playing, energizers, exercising, weighing pros and cons, homework, cookbook, summarizing results, and complimenting the participants. These components were adapted to the gender and cultural background of the different groups (e.g., letter of the week for the Surinamese patients could be about combining medications with nostrums; for Moroccan and Turkish women, it could focus on the fear of becoming addicted). Table 3 lists these program components.

Phase 2

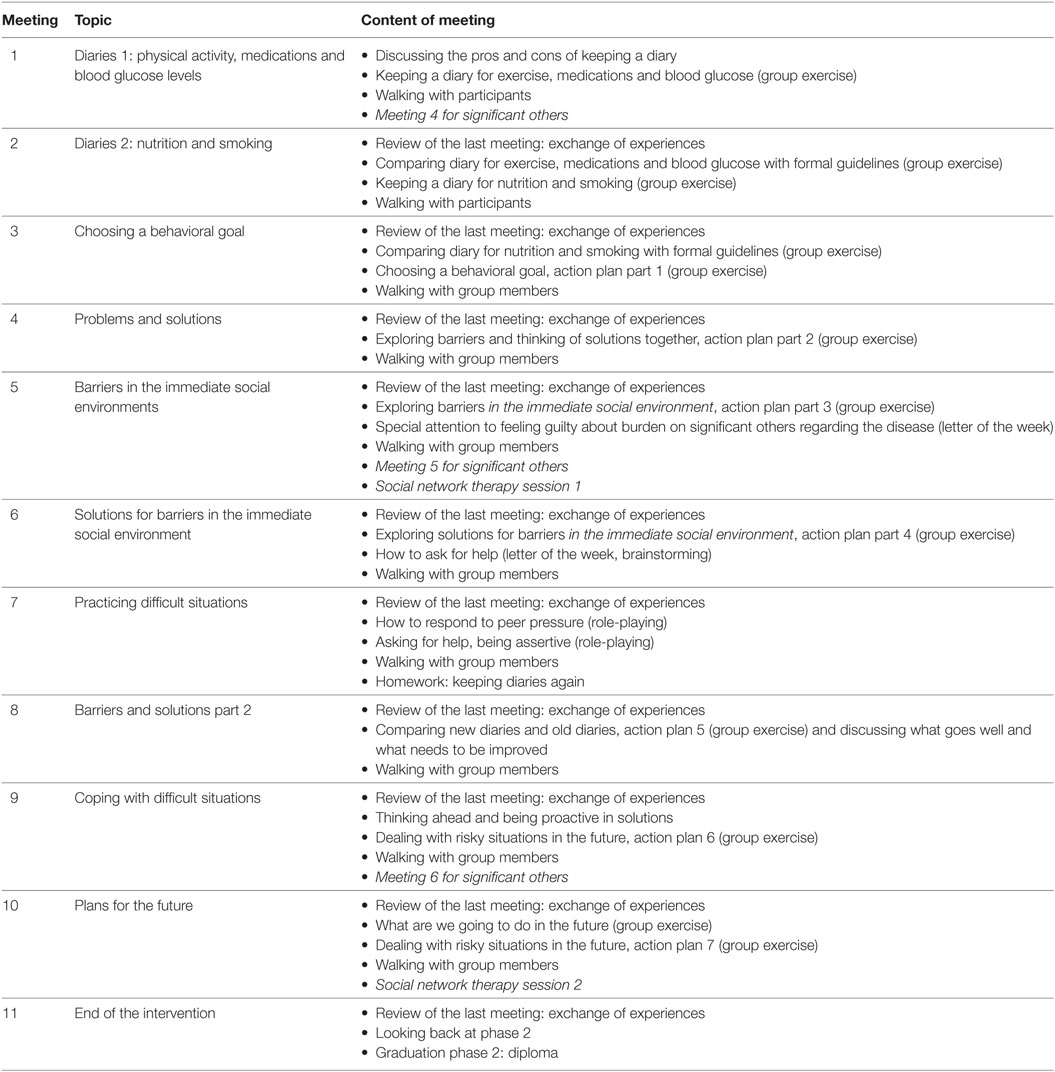

Phase 2 focused on providing the participants with a set of (proactive) coping skills. Every meeting centered around one aspect of making an action plan: keeping a diary (two meetings), choosing a behavioral goal (one meeting), discussing problems and solutions (one meeting), identifying barriers and formulating solutions for these barriers (two meetings), practicing difficult situations (one meeting), discussing barriers and solutions and coping with these barriers (two meetings), making plans for the future (one meeting) and celebrating the end of the intervention (one meeting). Also in this phase, the meetings consisted of interactive games and role playing exercises alternated with energizers. At the end of the meeting, the participants walked with each other around the neighborhood.

In this phase, the meetings no longer took place every week. Gradually, more time was placed between each meeting thereby stimulating the participants to undertake activities together, without the group leader being present. The aim was to make participants more independent and to stimulate communication and exchange of social support/social influences outside of the regular meetings. The first two meetings were only 1 week apart; meetings 2–5 took place biweekly; meetings 6–9 took place once every 3 weeks and, finally, meeting 10 took place 4 weeks after meeting 9. Table 4 presents an overview of the topics included in these meetings.

Recurring program components were homework, review of the last meeting and exchange of experiences, keeping a diary, group exercises, making an action plan, energizers, and walking with other group members (Table 5).

Review of the last meeting and exchange of experiences, the energizers, and walking with group members are described in Table 2. In phase 2, some of the energizers focused on remembering information from phase 1 through games and/or exercises (e.g., throwing a ball and naming a green food from the nutritional game when catching the ball). Instead of the group leader initiating walking together and determining how long it would take and where they would go, in phase 2 the participants were encouraged to take the initiative. Participants had to choose what they would like to do (e.g., swimming instead of walking) to make them feel more independent and to make walking (with group members) easier.

Meetings for Significant Others of Participants

For the meetings with significant others, each participant was asked to invite two persons that they considered important for their DSM. In each phase, three meetings were held for significant others during which the diabetic patients were not present.

Phase 1 focused on increasing practical knowledge about diabetes and its treatment. It also aimed to make the significant others believe that self-management is necessary and to create awareness about their important role in this self-management. Phase 2 focused on supporting a relative or friend with managing diabetes. The aim was to make the significant others aware that self-management is a shared responsibility between themselves and the patient, and to make them feel confident to support the patient (self-efficacy and skills).

Generally, we used the same program components that were used in the group meetings for participants. The program components were also alternated with energizers. Other program components (Table 6) included letting the significant others experience certain behaviors themselves to help them empathize with the participant.

Social Network Therapy Sessions (Participants and Their Significant Others)

In phase 2, both the participant and their significant others participated in two social network therapy sessions. Both sessions lasted about 25 min each and took place at the respondents’ home or, if preferred, at the community center.

During the first social network therapy session, the participant and their significant others determined a behavioral goal the participant could work on. This behavioral goal had to be based on the action plan used in the meetings for participants. Also, together with the group leader, they identified facilitators/barriers to achieve that goal and considered ways that the significant others could contribute to achieving this goal. The session ended with compiling a list of specific agreements that stipulated who will do what, and when, to achieve this goal.

The second social network therapy session evaluated the things that went well and the things that need to be improved. If necessary, a new/adapted list of agreements was complied.

Training and Supervision of Group Leaders

Powerful Together with Diabetes was delivered by various group leaders. The Turkish and Moroccan groups consisted of separate groups for men and women, whereas both men and women were included in the Surinamese group. Each group was guided by a group leader who was matched with the participants on ethnicity and gender. The leaders of the Dutch groups were diabetes nurses, GP assistants, and nurse practitioners, whereas the leaders of the Moroccan, Turkish, and Surinamese groups were migrant health workers.

All group leaders received 4 h of training before phase 1 and another 4 h before phase 2. In these training sessions, they participated in some of the intervention components themselves. They were also trained to use the handbook of phases 1 and 2, how to use the materials for the participants and how to guide and stimulate group bonding during the intervention. During these training sessions, they were provided with all intervention materials they needed during that phase. During the interventions, all group leaders had regular telephonic contact with the researchers; these calls helped with questions about the intervention and also provided practical advice. In this way, any problems were quickly and efficiently solved.

Step 1: Needs Assessment and Development of the Logic Model

According to the IM method, we conducted a needs assessment to gain an understanding of the determinants underlying DSM and the target population of this study.

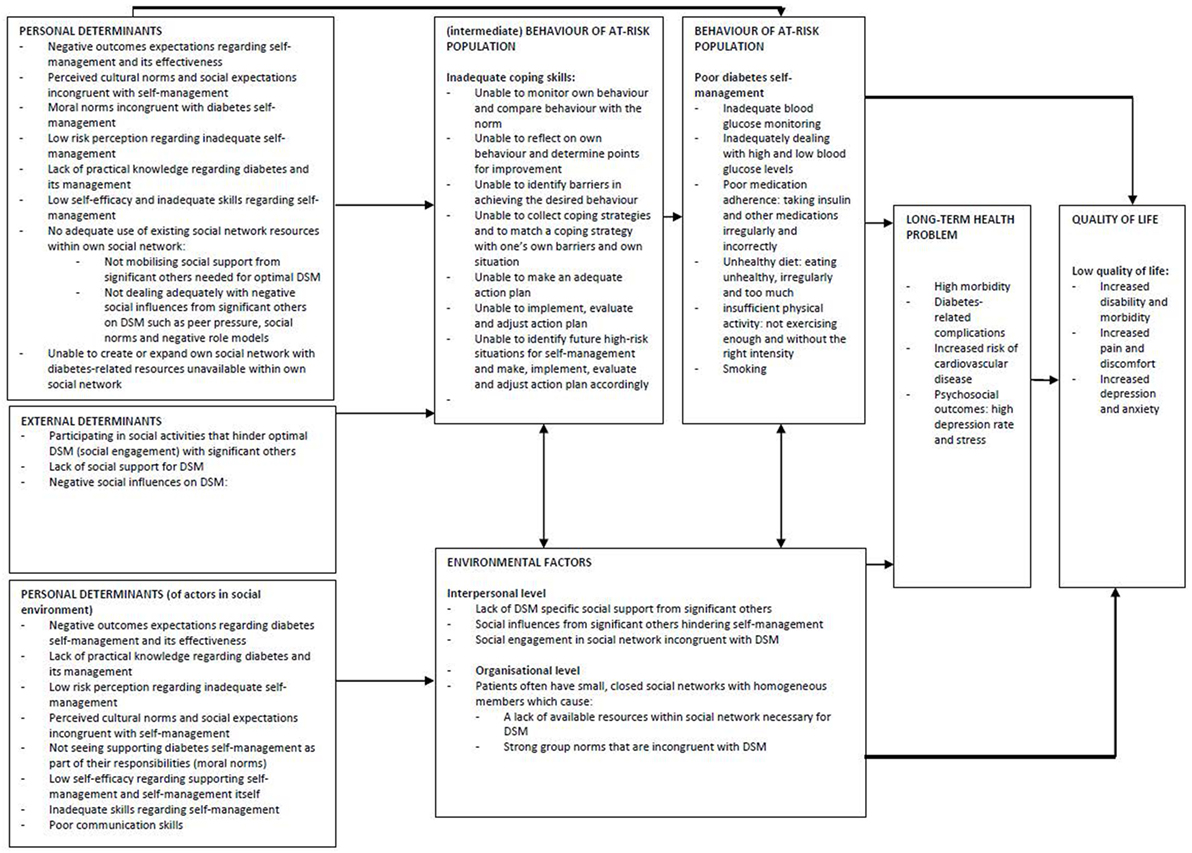

The results of the needs assessment are summarized in a logic model (Figure 1). A logic model describes the health problem, its impact on quality of life and its behavioral and environmental causes (35).

Our logic model is based on the results of the literature review and the qualitative study and outlines: (i) the personal and external determinants related to the self-management behaviors of the target population and (ii) also that of people in their immediate social environment. This section describes the development of the logic model.

Development of the Logic Model

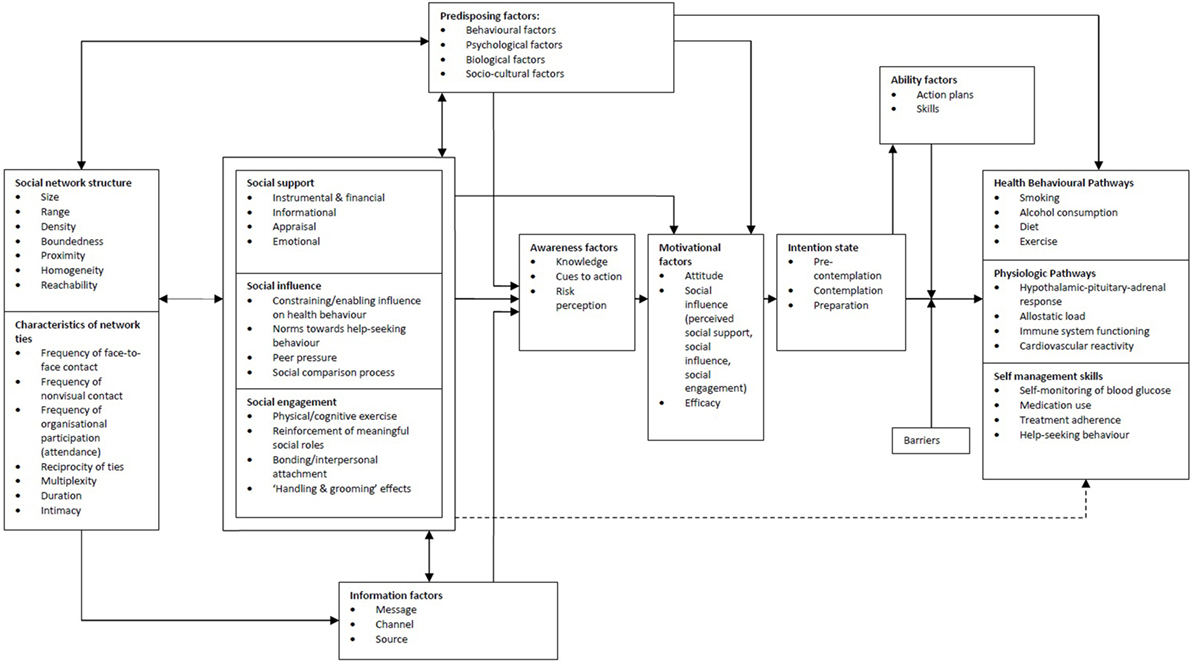

The needs assessment yielded many determinants related to the self-management of our target population. To explore these determinants, two theoretical models were applied that matched and further explained the results of the needs assessment, i.e., the I-Change model, and the transactional model of stress and coping (39, 49). The overall layout of the intervention is based on the I-Change model (49), which helped to decide in what order the determinants arising from the needs assessment should be addressed. However, because the needs assessment showed that the social network plays an important role in DSM, we combined the social network model of Berkman and Kawachi (50) with the I-Change model (Figure 2). Figure 2 shows the way we aimed for the intervention to address the determinants arising from our needs assessment. Our needs assessment showed that social influence might impact which health information reaches individuals (before awareness). We also observed that patients that received information, cues to action and/or were aware of their risks, were still hindered by social influences in their social environments (perceived social support, social influences, and social engagement) to change and maintain their behavior which is why social influences appears twice in Figure 2.

Figure 2. The I-Change model combined with the social network model of Berkman and Kawachi (50).

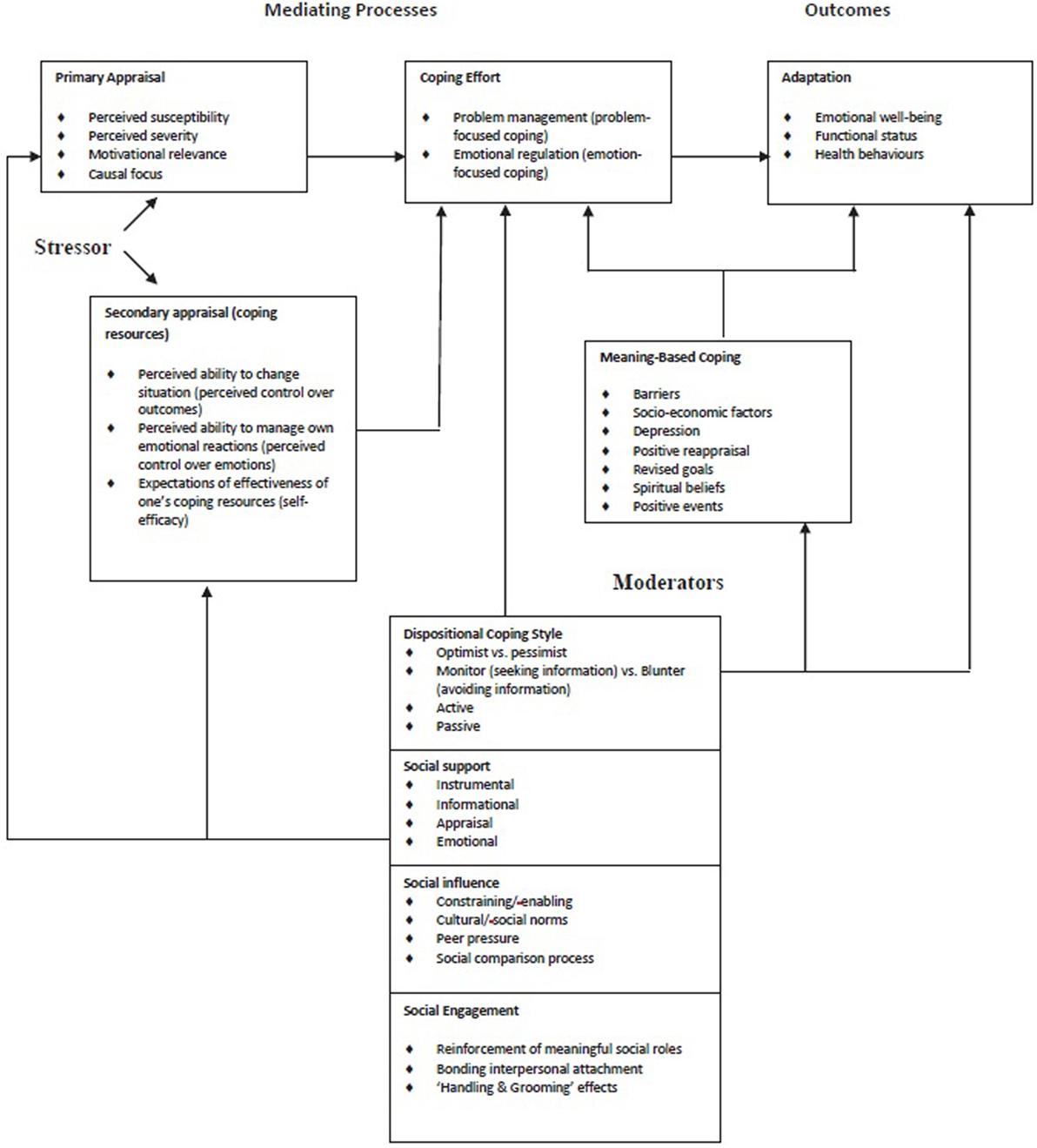

The needs assessment also showed that our target population has inadequate coping skills; this represents a challenge for the implementation of self-management behaviors. This finding is in line with other reports on coping and socioeconomic position. Therefore, in our intervention, we decided to emphasize the items “Ability factors” and “Barriers” of the I-Change model. These were extended by replacing them with the transactional model of stress and coping. Again, because the needs assessment stressed the importance of the social network, we extended this model with the social network model of Berkman and Kawachi (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Transactional model of stress and coping combined with the social network model of Berkman and Kawachi (50).

In short, the logic model assumes that our target population has a lower quality of life (increased disability/morbidity, increased pain/discomfort, and increased depression/anxiety) due to long-term health problems (high morbidity, diabetes-related complications, increased risk for cardiovascular disease, and negative psychosocial outcomes such as high depression rate/stress). These long-term health problems are related to poor self-management behaviors and ineffective coping skills caused by external determinants (social engagement/support/influences) and personal determinants (negative outcome expectations, perceived cultural norms and social expectations, moral norms, low risk perception, lack of practical knowledge, low self-efficacy, inadequate use of social network resources, and inability to expand social network with diabetes-related resources). It was also expected that the barriers (both external and personal) would be related to more distant determinants (such as unemployment, poverty, and marginalization) and other societal factors (in our original logic model) that might also influence long-term health problems. However, as Intervention Mapping stipulates focusing on the most important/changeable determinants, it was decided not to include these distant determinants but to consider them as the contextual environment in which the patients live. Although it is beyond the scope of this chapter to describe all the results of the needs assessment, the abovementioned determinants are in accordance with earlier studies on people with diabetes living in lower socioeconomic neighborhoods.

Therefore, here we describe only the most distinctive/new features of the intervention, i.e., specifically focusing on the social support/social influences affecting self-management, and on the educational requirements of these patients from a socioeconomically deprived neighborhood.

The Social Network and Self-management Behaviors

Diabetic patients that receive a lot of social support are better able to manage their diabetes than patients that receive little social support (22, 51–54). However, the immediate social environment of patients can hinder DSM. For example, negative interpersonal relationships (distrust, criticism, and dominance) also have a major impact on health and health behavior (23, 54–56). Non-supportive behaviors from family members and friends result in lower therapy adherence or lower metabolic control, and too much support (albeit intended by significant others) can be experienced as a form of interference (57–63). These social influences might have a stronger impact on health than social support alone (22, 50). There are indications that this is especially the case among people with lower health literacy (64). This stresses the need to examine the impact of all influences of the social networks of patients on self-management behaviors.

The social networks of individuals in socioeconomically deprived neighborhoods often consist of persons that are in the same situation as themselves. For example, in the Netherlands, low-income households are often clustered in the same neighborhoods and work environments (65). Moroccan, Turkish and Surinamese immigrants often live in neighborhoods and work in environments consisting mainly of people with the same non-Western ethnic background (66). For people in socioeconomically deprived neighborhoods, the neighborhood they live in and their family members generally form the most important source of their social contacts (65).

Social relationships between people that are in the same difficult situation (e.g., situations characterized by exclusion, stigmatization, and/or poverty) are often strong because of these shared experiences. The social networks they reside in are often smaller and less open than those of people with a higher socioeconomic status (26). The social networks of people in socioeconomically deprived neighborhoods often consist primarily of bonding social capital (social interactions between members of a homogeneous social network) and lack bridging social capital (social interactions that allow social network members to access resources other than those in their own social networks) (26, 65, 67).

According to the social network model of Berkman and Kawachi, the social network influences health through the following five mechanisms: (i) social support, (ii) social influence, (iii) social engagement, (iv) person-to-person contact, and (v) access to resources and material goods (50).

Social support consists of emotional, instrumental, informational and appraisal support. Social influence consists of constraining/enabling influence on health behavior, social norms, peer pressure, and social comparison processes. Social engagement consists of physical/cognitive exercise, reinforcement of meaningful social roles, bonding/interpersonal attachment, and “handling and grooming” effects. Moreover, the social network approach assumes that not every social network is necessarily beneficial for the health of its members. Also, some social networks are better in promoting health than others, but not everyone has equal access to these social networks (26).

Small, closed, and dense social networks, like those of our target population, might positively influence health because the exchange of social support is often high (26). However, the strong interdependence between social network members can also prevent members from acquiring new information and “getting ahead” in life (65, 67, 68). Small social networks are also associated with lower therapy adherence and lower metabolic control (59, 69). In addition, this type of social network is known to impose strong social norms on its members; when these social norms are incongruent with health behaviors, these social networks often have an adverse influence on the health of its members (70).

Social Network and Self-management Behaviors in Patients from Socioeconomically Deprived Neighborhoods

Five major themes related to the role of significant others in self-management behaviors emerged from the qualitative data of our needs assessment: (i) trying not to bother others, (ii) trying not to stand out at social events, (iii) peer pressure at social events, (iv) social norms regarding medication use and physical activity, and (v) having no “allies” in the immediate social environment.

Trying Not to Bother Others

Most respondents indicated that they considered their diabetes to be their own responsibility and did not want to bother their significant others (mostly partners, children and friends) with their condition. Most respondents did not see any advantage in asking for social support and indicated that they were capable of managing their diabetes by themselves.

As a result, these respondents often felt “bad” in front of their significant others if they had to take their diabetes into account. For example, some respondents said that they felt sorry for their partners because they always have to set the alarm clock to take their insulin on time, even when their partner wants to sleep. They often did their best not to burden their significant others with their self-management. As a result, our respondents (as well as the participants in the diabetes forum) indicated that they always have to be the stronger person, which demands a lot of self-control.

I often have to watch my husband eating a whole bowl of custard, cream and chocolate flakes. That’s really difficult, but I don’t want to put him under pressure – I’m the one who’s sick, not him … (Patient).

The health-care professionals indicated that relatives often know very little about diabetes and/or the ways to help out with self-management, or they think they are being helpful whereas this is in fact perceived differently by the diabetic patients.

Not asking for support also affected the ability of the respondents to make changes in their self-management. For example, all women from the ethnic minority groups indicated that it is difficult to cook something different, or serve more healthy food, when their significant others do not like it and/or refuse to eat it.

(…when serving brown rice instead of white rice): “Then they ask – what’ve you made now? Coconut?” (Patient).

Trying Not to Stand Out during Social Events

Most respondents were aware that they and their significant others shared the same unhealthy lifestyle. For most respondents, adhering to the diabetes guidelines meant behaving differently from their significant others. Most respondents did not want to draw attention to themselves and their diabetes, i.e., they did not want to stand out in general and especially not during social events.

Particularly the combination of not wanting to bother others and trying not to stand out during social events proved detrimental for their self-management behaviors. When eating at the house of a friend/relative, patients tried to blend in with the others and would not ask the host to take their diabetes into account (e.g., to eat at a certain time, or to make/buy special foods). This often caused uncomfortable situations (e.g., not eating everything that was served, or having to ask for something to eat before dinner) and often required extra self-management skills (e.g., eating in advance, rearranging their insulin dosages).

Social parties were also experienced as being difficult. The respondents did not want to bother the host with questions about the ingredients or ask him/her to make something especially for them. Therefore, they often did not know what they can/cannot eat. Also, it is difficult to predict how often people might come around offering snacks and what these snacks might contain. This combination of not asking for support and trying not to cause a fuss also made going out to dinner difficult. Respondents said they sometimes had to wait too long for their food and, because they do not always know what the ingredients are, this makes injecting the right amount of insulin a challenge.

Trying to “blend in” also affected their medication use. Most respondents did their best not to inject insulin during social situations. Some said that the looks from other people made them feel uncomfortable, others said that their relatives did not like to witness an injection (fear of needles), and sometimes asked annoying questions, or interfered too much.

Peer Pressure at Social Events

The respondents reported a lot of peer pressure and temptations at social events that affected their diet. Most said that they found it unpleasant when everybody was eating, whilst they either cannot or should not eat that particular food.

The Turkish, Moroccan, and Surinamese respondents indicated that the food plays a central role in their daily life. Offering food is seen as a sign of hospitality and it is customary to prepare extra food for guests. Refusing food is seen as impolite. Although respondents knew that they should not accept all the food that is offered, they did not want to hurt anybody’s feelings. Therefore, they often “act” as though they (temporarily) do not have diabetes, or try to avoid these situations as much as possible.

Almost all respondents had difficulty in resisting temptation and often felt under pressure to eat unhealthy/too much food, especially in the presence of negative role models.

“… when you’re at a party and other people with diabetes eat really unhealthy things”. Or ‘they’ (people at a party) say: “Well, this one and that one have got diabetes - and it’s OK for them” (Patient).

The respondents handle these situations differently: some accept that their blood glucose levels will be too low or too high.

Social Norms Regarding Medication Use and Physical Activity

The needs assessment showed that social norms were especially prevalent in medication use. All respondents indicated that they prefer not to take any medication at all. Medications are often regarded as “chemicals” that are not good for their body. Most respondents did not see their medication use as something permanent and hoped that 1 day they could live without medication. This was confirmed by the health-care professionals who reported that patients often think that if they lose weight they can live without medication. Most respondents had a strong aversion to insulin and indicated that they definitely did not want to use insulin in the future.

Then (when you have to use insulin) – that’s when you’re really sick (Patient).

According to the health-care professionals, Hindustani Surinamese persons often prefer not to take medications and have a strong tendency to see if they can manage without them. They fear that the medications will damage their kidneys; moreover, when they feel unwell they often skip their medication. Especially the use of insulin is experienced as a problem by these patients as it is associated with severe diabetes-related complications. We also observed that Surinamese patients sometimes try to “cleanse” their body by not using medications for a longer period of time. In addition, the interviews showed that Surinamese patients often get advice from other persons not to take their medications but to use “nostrums” (remedies from non-physicians) such as certain herbs or vegetables.

Turkish and Moroccan patients often have doubts about the medications prescribed by their physician. In Morocco and Turkey, physicians generally prescribe more medications and behave in a more authoritative way. Physicians in the Netherlands tend to ask more questions, which is interpreted by patients as lack of competance (3). The health-care professionals reported that, after the summer, these patients often arrive at consultations with a bag of (unnecessary) “new” medications they received from physicians in Morocco or Turkey. They also indicated that, among Moroccan and Turkish men, medications are sometimes associated with impotence.

During Ramadan, 60–80% of Turkish and Moroccan patients is non-adherent to their medications (71). Individuals who cannot participate during Ramadan due to illness are supposed to compensate by giving money to the poor. However, interviews with professionals revealed that this can be problematic when the individual involved has little/no money. According to the professionals, some alternatives, such as taking food to the poor, are also difficult because this is not socially accepted behavior in the Netherlands.

Social norms also affect physical activity. For example, Moroccan, and Turkish women mentioned they had no money to go to the gym, and that simply “walking around” was not an option for them. They were worried about what people in the neighborhood might think if they just “walked around” without going anywhere/without a valid reason. This situation was confirmed by the health-care professionals.

No “Allies” in the Immediate Social Environment

Most respondents said that they only knew a few people with diabetes and, often, they did not identify with them. For example, these acquaintances had different ways of dealing with their diabetes or were worse off than themselves, making it difficult to exchange ideas, ask questions, or share experiences. This affected multiple self-management domains. Also, quitting smoking was difficult because they were often surrounded by smokers and felt they were the only ones trying to quit.

… just try stopping when you’re living in a house with five smokers! (Diabetes forum).

Also, especially Dutch respondents said that they did not go to the gym (or go walking) because they had no one to go with, or had no one who thought it necessary to go to the gym.

Considerations Regarding Health Promotion in Patients from Socioeconomically Deprived Neighborhoods

The needs assessment also provided us with considerations related to health promotion in patients from socioeconomically deprived neighborhoods that needed to be taken into account when developing a group-based intervention for patients from socioeconomically deprived neighborhoods.

The respondents often had busy lives: they spend a lot of time taking care of their family (e.g., grandchildren and chronically ill relatives) and/or working. Some respondents felt stressed due to financial problems, or problems with raising their (teenage) children, or were worried about relatives living abroad. This was confirmed by the health-care professionals who reported that these patients often had difficult lives before the additional problem of developing diabetes.

You’re already having a tough time - then you also get one of the most difficult diseases that exist (Health-care professional).

Because of this, their disease was often given a low priority. Although they did what they had to do for their diabetes, most did not actively seek information about diabetes themselves. Some respondents expressed the desire for the diabetes nurse or the dietician to simply tell them what they had to do. According to the respondents, the diabetes regime is always complicated because one has to constantly think about the choices to be made and it is never simply “yes” or “no.” The health-care professionals stated that these patients do not necessarily want lots of medical information about their disease, but mainly want to know what they have to do and what they cannot do.

Second, the interviews revealed that most respondents have a low level of education, i.e., the majority had attained no, or only one, diploma. They had little learning experience, or their learning experiences were mostly negative, e.g., being unable to follow the classes, or being bored during lessons. These respondents were not convinced that “education” would help them to better understand their diabetes; they said that they were not suitable to learn things, or that “learning was not really their thing.” From our observations during the intervention “Dealing with diabetes” we knew that most participants had little experience with following classes. The more traditional educational methods (e.g., the teacher talks and the audience listens) did not seem suitable for this population, e.g., they had a short attention span and became distracted when they did not understand the information presented. Instead of asking questions, the participants generally chose to focus on something else (e.g., their telephones, or other participants).

Moreover, reading and writing was often a challenge for these respondents; this was confirmed by the interviews with the professionals. Also, the level of knowledge about diabetes differed between the respondents; some were unable to name one thing they had to do for their diabetes and could not recall whether they had ever heard of high/low blood glucose levels, whereas others could distinguish between their medications and also explain the basics of diabetes.

The needs assessment also revealed factors that might be important for the group process during the intervention. Most respondents were rather direct/blunt when we first met them (“rough diamonds”); however, this type of attitude can be problematic in a group where everybody needs to feel safe to speak freely. Moreover, it may be a challenge to find a balance between dealing with one’s problems in daily life whilst also focusing on the aims of the intervention.

Conclusions of the Needs Assessment

In conclusion, patients from socioeconomically deprived neighborhoods generally have social networks that seem less beneficial to self-management because of their small size and the limited ability to acquire new information. Furthermore, the strong social norms these social networks impose on their members seem incongruent with self-management behaviors. Moreover, these patients receive little social support for self-management behaviors because they often lack sources of support in their social networks and are reluctant to ask for social support or show others that they need it. These patients find it difficult to deal with influences from their social network such as various temptations, peer pressure, negative role models, and social norms. Moreover, for these patients, some of their significant others are unaware that they can/should help, or they simply do not know how to help.

During interventions for patients from socioeconomically deprived neighborhoods, the following aspects should be taken into account: low outcome expectations regarding education and low motivation for education; a low priority for diabetes; a desire for practical information; reading and writing difficulties; differences in knowledge about diabetes and factors that might affect the group process during the intervention.

Step 2: Creating Performance and Change Objectives

The second step in IM is the development of matrices of change objectives that describe what needs to change in behavior and the environment to improve health and quality of life (35). We specified change objectives that describe what needs to change to achieve performance objectives, which in turn will lead to changes in behavioral and environmental conditions that will lead to accomplishing the program goals (35).

Formulating Program Goals

The needs assessment showed that our target population encountered influences that affected their self-management within their social networks (bonding social capital), including lack of social support, peer pressure, and social norms but also experienced difficulties in accessing other resources (bridging social capital) outside their social networks, such as new information, an ally/buddy, and other positive role models. In addition, they did not make adequate use of the social network resources already present in their social networks (asking for support, not dealing adequately with peer pressure, social influences and negative role models).

Therefore, based on the needs assessment and consultations with the experts, when we formulated program goals it was decided that our intervention should not only focus on the patient and their immediate social environment (bonding social capital) but also on bringing diabetic patients in contact with fellow patients (bridging social capital) thereby extending their social networks with diabetes-related resources. We aimed to extend the participants’ social networks with more diabetes-related resources while simultaneously making their own social networks more diabetes friendly. Accordingly, the following program goals were formulated for the social network that should be achieved by participation in the intervention:

(1) Extend the participants’ diabetes-related social networks, facilitating the exchange of social support and positive social influences with group members,

(2) Increase the participants’ ability to handle social influences that hinder their self-management such as norms, peer pressure, and temptations,

(3) Increase the engagement and support of the participants’ significant others in their self-management.

Performance and Change Objectives

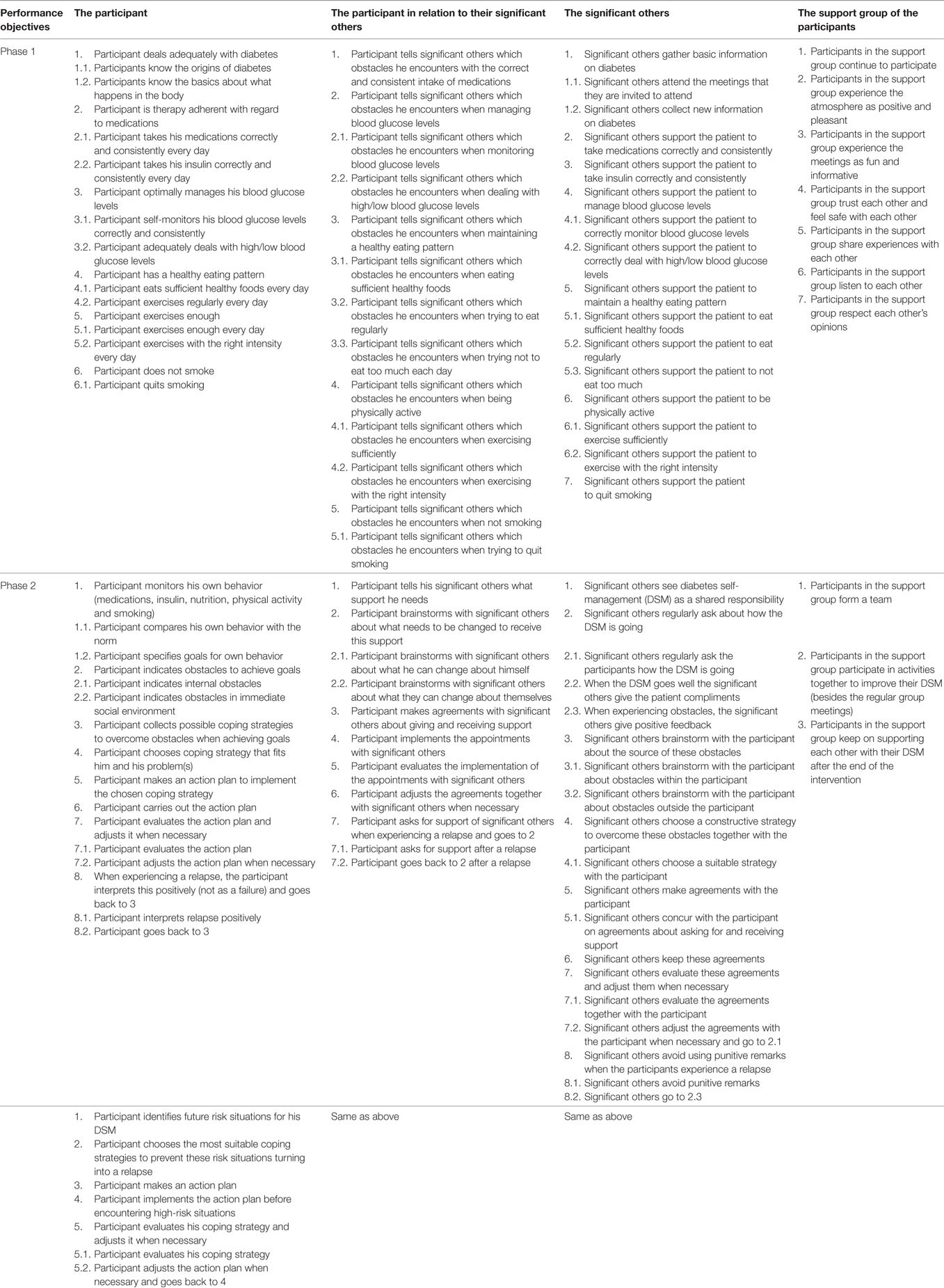

This section focuses on the performance and change objectives that were formulated to achieve the program goals for the social network. The program goals for the social network were translated into performance objectives and change objectives. Table 7 provides an overview of the performance objectives for the entire intervention. The health-promoting behaviors of the social network are formulated as performance objectives but also as change objectives: objectives for determinants supportive of self-management behaviors.

We organized two brainstorming sessions with five researchers who studied diabetes, nutrition, overweight and physical activity among patients in lower socioeconomic groups, or in minority groups. During these sessions, we checked the content of our performance objectives against their findings and experiences. Then, three researchers who had experience with Intervention Mapping, critically reviewed our performance and change objectives to see if they matched the Intervention Mapping conditions and were suitable to build our intervention on. Based on these meetings, our performance objectives were adjusted where necessary.

The performance and change objectives were formulated on the following four levels:

(1) the participant,

(2) the participant in relation to their significant others,

(3) the significant others,

(4) the participant’s support group as part of the intervention.

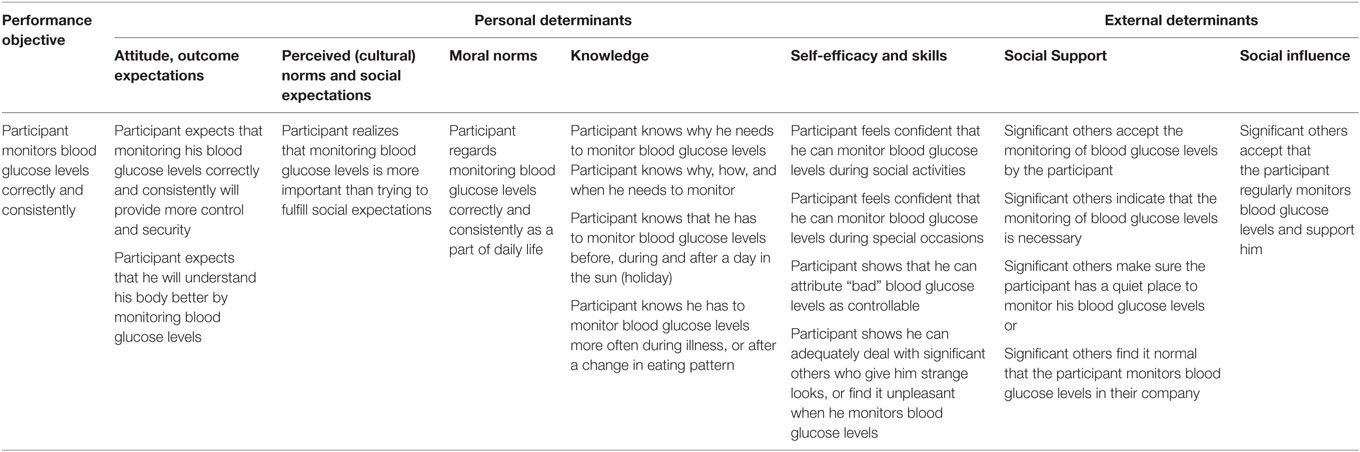

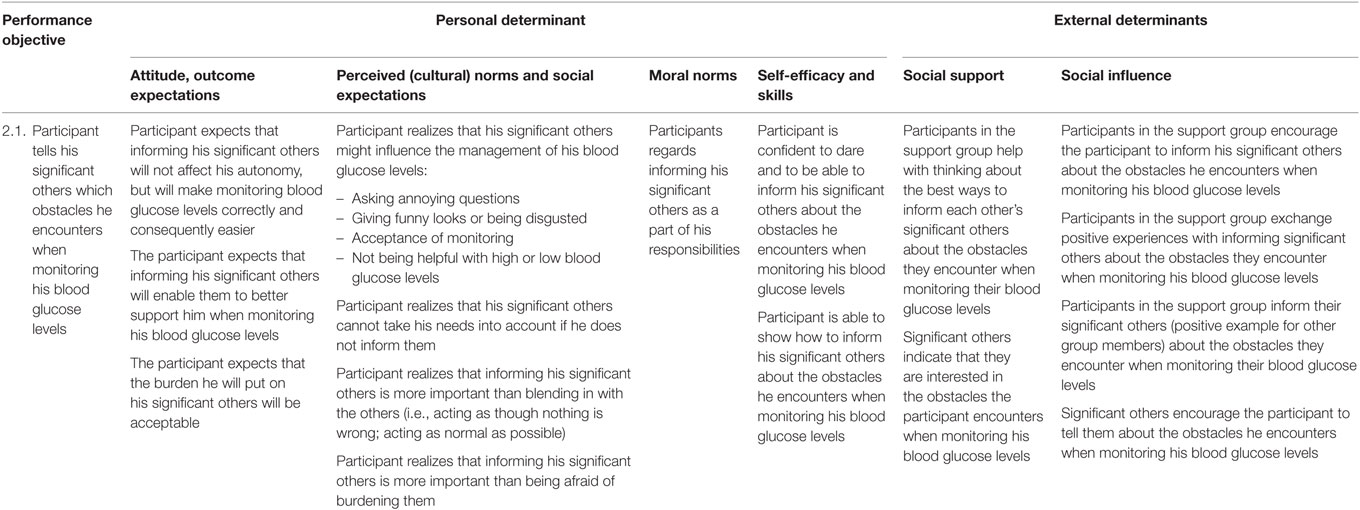

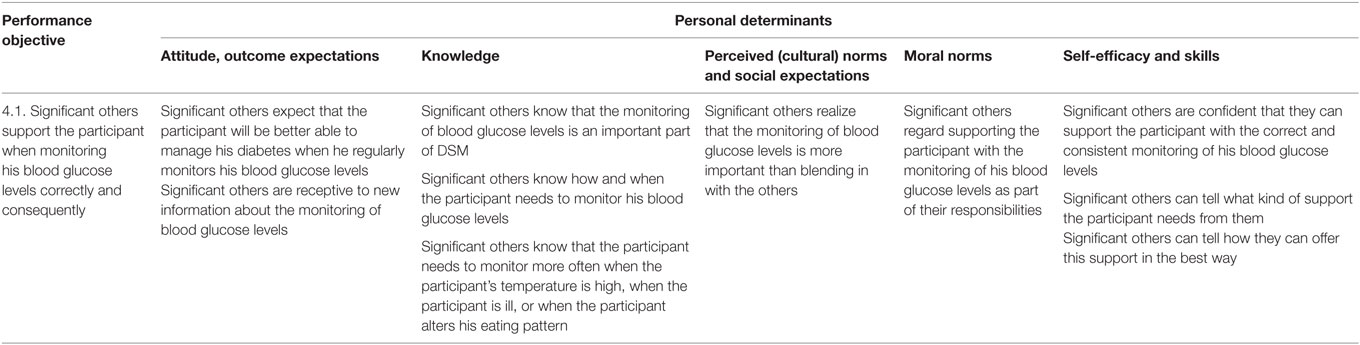

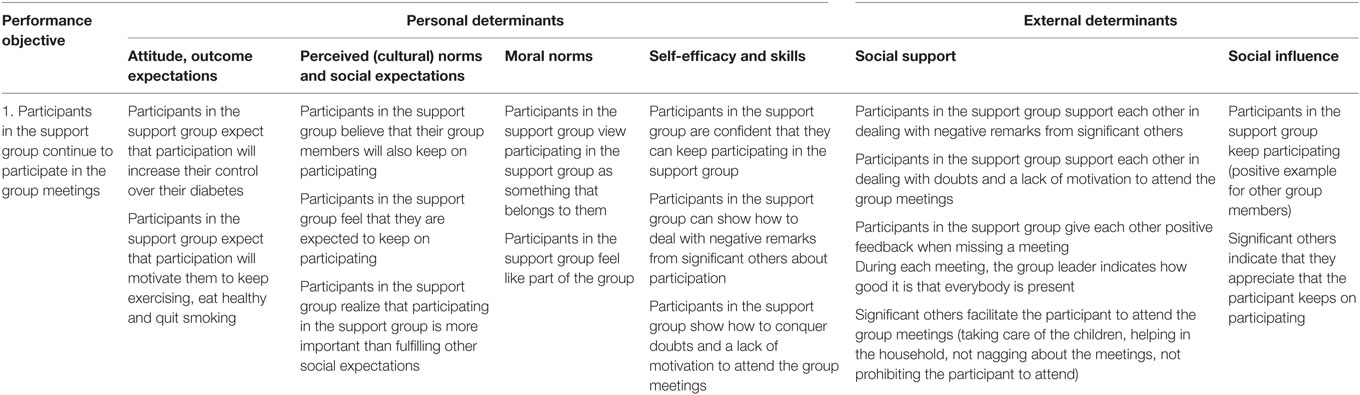

Tables 8–10 provide an example of the change objectives for the performance objective “Patient adequately monitors his/her blood glucose levels,” “Patient explains obstacles during monitoring of blood glucose levels to significant others,” and “Significant others support patient with adequate monitoring of blood glucose levels” (levels 1–3). Because we anticipated challenges in the group process of the intervention (which was a key aspect of this intervention) we also formulated performance and change objectives for level 4, i.e., the participant’s support group as part of the intervention (Table 11).

Step 3: Selecting Theoretical Methods and Practical Strategies

In this step, we selected change methods based on the performance and change objectives. Based on these change methods we created practical strategies that formed parts of the program lay out (35). For this intervention, the practical strategies and program components were developed together with a psychologist who has considerable experience in working with lower socioeconomic groups. When selecting theory-informed intervention methods/practical strategies and producing program components/materials, the literature and other ongoing lifestyle interventions were scrutinized for methods and strategies that would be suitable for our target population. These practical strategies/program components were submitted twice to a panel of migrant health workers with a Turkish, Moroccan, and Surinamese background (n = 6). In addition, panel members were consulted individually about the specific cultural groups in our target population. Finally, some of the intervention components were pre-tested among the target population by means of focus group discussions (n = 3) in which we “practiced” some of the intervention components.

The next section describes the ways we used our needs assessment to choose methods and strategies for the intervention.

Methods and Strategies Specific for Patients from Socioeconomically Deprived Neighborhoods

This section describes the ways we considered the results of the needs assessment regarding our methods/strategies for our target population. From the needs assessment we knew that our target population had little (or primarily negative) experiences with education. Therefore, when selecting our theoretical methods we aimed to make learning as much fun and as interesting as possible. The aim was to make our participants curious about diabetes-related topics and make participation a positive experience by focusing on the abilities of our participants rather than on their shortcomings.

One of our strategies included an inductive educational approach (72). In contrast to deductive education that stems from theory, inductive education is built from the students’ experiences. Instead of telling students what they need to know from a theoretical point of view (deductive approach), we let the students practice with a problem they can relate to and slowly add information and theory to their understanding (inductive approach). Using this approach, the group leader can also investigate what the participants already know and which knowledge is incorrect or new (since the amount of foreknowledge about diabetes differed). Therefore, an inductive approach focuses on the abilities of the students and is closely connected with their interests (72). An example of the inductive approach is the game about nutrition: the participants had to solve a puzzle (what foods are green, which are orange and which are red?) together. The aim was to let them brainstorm together, focus on what they already knew, let them discover themselves what they did not know, and add to their knowledge and understanding where necessary.

To make learning as much fun as possible, it was important that the participants did not feel as though they were students but, nevertheless, felt that they benefited from each meeting. At the beginning and during the intervention, it was emphasized that they could help other participants with their own experiences and feedback (participatory problem solving). We did not use traditional educational strategies (such as teaching in front of a classroom) but non-traditional intervention strategies such as games and role-playing, with (fun or relaxing) energizers to optimize the attention span. The participants were encouraged to relate what they would “take home” from the intervention to help them realize what they had learned, or their particular significance for the other participants.

We also focused on self-affirmation by accentuating the personal qualities of the participants. This is a method to stimulate cognitive developments (72) and avoid dismissive/defensive reactions toward information perceived as a threat, and makes participants more perceptible for new information (73, 74). Practical strategies included giving each other compliments and constructive feedback, energizers, and sharing the positive news of the week at the start of each meeting.

To ensure a close connection to the interests of our participants, we involved them in the intervention through active learning to increase relevance and interest. This meant that the participants had direct influence on the topics and rehearsal situations addressed during the intervention.

Because most participants had a low educational background and problems with reading/writing, it can be difficult for them to learn/remember new information. Therefore, we used practical educational methods that enabled participants to remember the provided information and to practice real-life situations. Practical strategies included skills training with guided practice and feedback (practicing situations) and “chunking” (breaking up long pieces of information into easy to remember chunks). Also, a limited amount of information was provided at each meeting, and information from the previous meeting was always repeated at the latest meeting. In phase 2, the participants had to plan coping responses with the help of an action plan; this plan mainly consisted of the use of stickers and pictures.

Finally, to anticipate the varied and compelling priorities of our participants, the methods and strategies applied in this intervention focused on dealing with difficult situations that affected self-management; this was to promote/ensure long-term results. Therefore, the focus was on skills training with guided feedback. For example, participants exercised in their own neighborhood, and went to their own supermarket with a dietician to select healthy foods. Barriers that were encountered (e.g., an unsafe neighborhood, the higher costs of healthy food) were dealt with during these outings (e.g., exercising while shopping for groceries, finding alternatives that are also healthy, etc.).

Methods and Strategies for the Social Network

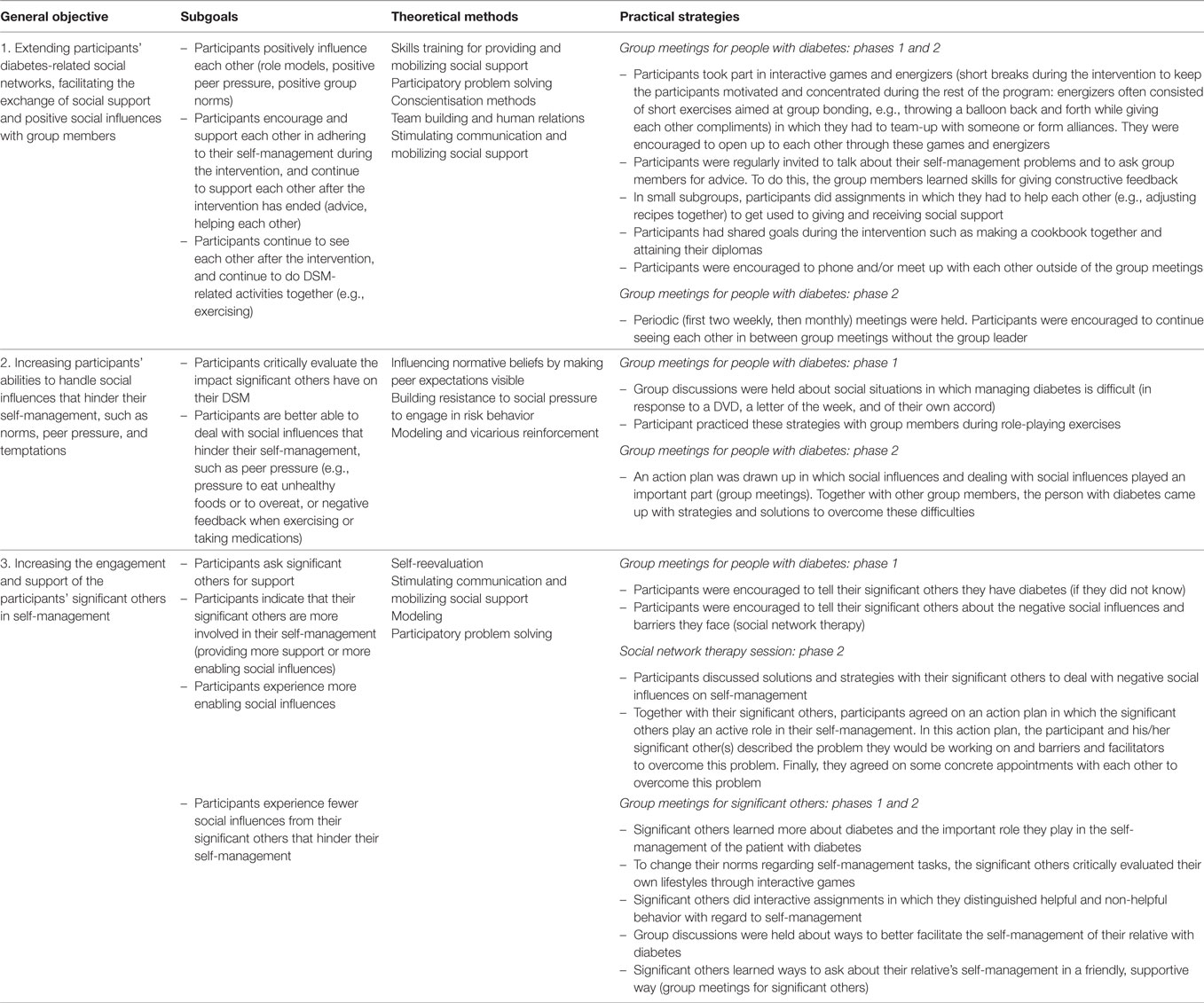

This section entails a description of the methods and strategies specific for the health-promoting behaviors of the social network. The needs assessment indicated that for interventions using group processes, it is important to consider how to shape these group processes for the participants. It is also important to consider how to balance dealing with personal problems and the goals of the intervention. Moreover, participants might have personal characteristics that can hinder the use of the group process during the intervention. Table 12 presents an overview of the methods and practical strategies for the health-promoting behaviors for the social network.

For this intervention to be successful, it was important that the participants became a mutual support group, i.e., support each other and positively influence each other in self-management behaviors. Therefore, during the intervention we focused on the group process and on establishing a safe learning environment, by increasing trust and the exchange of emotions/experiences between participants. The methods used to achieve this included team building and human relations, stimulating communication and mobilizing social support, and skills training for providing and mobilizing social support. Participants made agreements about trust and also agreed to treat the experiences/stories shared within the group in a confidential way. They participated in interactive games in which they had to team-up and form alliances. During the intervention, they established shared goals (e.g., making a cookbook together), were encouraged to share personal stories (e.g., by relating their positive news of the week), and the energizers were aimed at getting to know each other, having fun together, and appreciating each other (e.g., by giving each other compliments). Group members practiced giving constructive feedback and giving/receiving social support before implementing this in real-life situations.

The second goal was to increase the participants’ abilities to handle the social influences that hindered their self-management. Methods included the following: influencing normative beliefs by making peer expectations visible, building resistance to social pressure, modeling, and vicarious reinforcement. Practical strategies focused on making social influences on self-management visible by means of group discussions and stories about role models. Furthermore, strategies included helping fictional people with self-management problems, followed by giving advice to/asking advice from fellow group members. In phase 2, the participants made an action plan that focused on how to manage their diabetes within their social environments together with group members; in addition, they practiced the skills needed for implementing this action plan during role-playing exercises, followed by feedback from the group members and group leader.

Finally, the intervention aimed to increase the engagement and support of significant others in self-management behaviors. Methods to achieve this included self-reevaluation, stimulating communication and mobilizing social support, modeling, and participatory problem solving. Practical strategies included group meetings for significant others, in which the significant others learned the difference between supportive and non-supportive behaviors, communication skills, and how they might contribute toward self-management. Other strategies included the social network therapy sessions in which the patient and their significant others made an action plan together, which specified what each of them could do to achieve the joint goals.

Discussion

Powerful Together with Diabetes primarily consists of non-traditional intervention strategies. The Intervention Mapping method focuses on matching theory and evidence based methods to the change objectives formulated in phase 2 of the intervention development and provides a state of the art overview of these methods (75). This helped our planning group to think out of the box, select the right methods and to create practical strategies that combined multiple methods at the same time.

Furthermore, the overviews of the change objectives and their matching methods and strategies facilitated our evaluation design. These overviews together with the data collected throughout the intervention period provided us with a thorough understanding of why certain aspects of the intervention worked while others did not.

However, lessons can be learned for future health promotion in this target population. First, though the intervention was appreciated and experienced as useful we noticed that the intervention did not fully fit the needs of the participants and seemed not totally in concordance with their daily lives. During the intervention, we realized we did not know the full extent of the problems those in our target population faced in their daily lives. Getting to know this target population takes time (76). Because of the nature and long time span of the intervention, we got to know the participants and their daily lives very well. Although the social network appeared to be a real problem for their DSM, this target population also faces other important problems. During the intervention, we noticed it did not fully meet the participants’ needs and did not seem entirely consistent with their daily lives.

Our participants often had multiple conditions, were experiencing financial problems, marital problems, domestic violence, or were caring for sick relatives. These problems had a major impact on DSM, and the priority they gave to DSM. Although the intervention aimed to teach participants to deal with these problems so they could self-manage their diabetes, this was not always realistic. For example, if your husband or son is abusing you, it is very unlikely he will become a supportive partner in your DSM.

Intervention Mapping stresses, the importance of conducting a needs assessment before developing the intervention. A health-related needs assessment includes a study of the determinants of behavior and environmental contributors to health problems or health risks (75). To do this, IM increasingly stresses the importance of participatory planning. Important elements of the needs assessment are the involvement of a planning group with planners, implementers, and program participants, and the involvement of the community throughout the whole project. Community involvement is needed to prevent a top-down, outsider approach (75, 77, 78).

IM thus advocates collaboration between community members and health professionals from the start of a project. Other researchers have also reported this to be a positive factor that helped in the development, adoption, and evaluation of an intervention (79–82). According to some studies, it can be difficult for health promoters to include the concerns and issues of the community because of the extra time needed for community involvement, and the often top-down organization of intervention development and top-down funding for these projects (78, 83).

When we started our research project, there was less emphases on participatory planning than there is now in the most recent version of the IM book (31, 35). Besides this, we also experienced the abovementioned limitations (a lack of time and top-down funding). When conducting our needs assessment, we performed all of the research activities as if we were developing a social support (and later on, a social network-based) intervention for patients with suboptimal glycemic control, as stipulated in our research grant proposal. This was the focus of the literature search, the interviews, the analyses of previously conducted interviews, and the diabetes forum. We did consult a panel of migrant health workers with Turkish, Moroccan, and Surinamese backgrounds multiple times. However, due to financial and time constraints, we did this fairly late in the process (after our needs assessment was completed) and asked for feedback only on topics related to our chosen focus, the social network.

Other factors complicated community involvement as well. We did not know the exact neighborhoods in which the intervention would be implemented, and so where our participants would live (which community to address). Also, we planned to aim the intervention at a very specific target population (with suboptimal glycemic control) and did not want to create false expectations within a community.

In hindsight, we conclude that the intervention could have been improved by investing more in participatory planning. If we had involved the target population and their community from the start and asked them (with no predetermined focus) what they thought would be the best when it comes to management of their diabetes, we might have come up with a different intervention, one with closer connections between the lives of our participants and the intervention (77, 83, 84).

In some of the interventions that report positively on community involvement, the researchers involved the community before applying for funding. They chose the study design and applied for funding together with the community or based on the results gathered together with the community (79, 82). However, as funding programs are often clustered around specific themes or have a predetermined focus (e.g., “preventing overweight by influencing lifestyle factors” or “socioeconomic health disparities, prevention and reduction through integrated local policies”) that provide a research direction, this might complicate involving communities without a predetermined vision (83, 85, 86).

In hindsight, it would have been better not to decide beforehand what the nature of the intervention would be, but to decide this based on an open needs assessment together with the target population and their community. Funding organizations might facilitate this community involvement by allowing for a longer planning period, and by allowing great flexibility in the area of focus and topics that will be investigated in one project (83, 87–89).

Ethics Statement

This study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the Academic Medical Centre (AMC) in Amsterdam. The participants provided written informed consent for the study and the study procedures.

Author Contributions

CV coordinated the study, developed the intervention, constructed the design, and drafted the manuscript. VN and KS developed the study, constructed the design, and revised the manuscript. PU, BM, and GN participated in the design of the study and revised the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The reviewer CH and handling editor declared their shared affiliation.

Funding

This work was supported by the Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development (ZonMw) [project number ZonMw 76500003].

References

1. Bachmann M, Eachus J, Hopper C, Davey Smith G, Propper C, Pearson N, et al. Socio-economic inequalities in diabetes complications, control, attitudes and health service use: a cross-sectional study. Diabet Med (2003) 20(11):921–9. doi:10.1046/j.1464-5491.2003.01050.x

2. Connolly V, Unwin N, Sherriff P, Bilous R, Kelly W. Diabetes prevalence and socioeconomic status: a population based study showing increased prevalence of type 2 diabetes mellitus in deprived areas. J Epidemiol Community Health (2000) 54(3):173–7. doi:10.1136/jech.54.3.173

3. Espelt A, Borrell C, Roskam A-J, Rodríguez-Sanz M, Stirbu I, Dalmau-Bueno A, et al. Socioeconomic inequalities in diabetes mellitus across Europe at the beginning of the 21st century. Diabetologia (2008) 51(11):1971–9. doi:10.1007/s00125-008-1146-1

4. Snijder MB, Agyemang C, Peters RJ, Stronks K, Ujcic-Voortman JK, van Valkengoed IG. Case finding and medical treatment of type 2 diabetes among different ethnic minority groups: the HELIUS study. J Diabetes Res (2017) 2017:9896849. doi:10.1155/2017/9896849

5. Goldman DP, Smith JP. Can patient self-management help explain the SES health gradient? Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2002) 99(16):10929–34. doi:10.1073/pnas.162086599

6. Nederlandse Diabetes Federatie. NDF Advies Diabeteseducatie. Amersfoort: Nederlandse Diabetes Federatie (2005).

7. Onwudiwe NC, Mullins CD, Winston RA, Shaya AT, Pradel FG, Laird A, et al. Barriers to self-management of diabetes: a qualitative study among low-income minority diabetics. South Afr J Diabet Vascu Dis (2014) 11(2):61–5.

8. Wolff K, Cavanaugh K, Malone R, Hawk V, Gregory BP, Davis D, et al. The diabetes literacy and numeracy education toolkit (DLNET) materials to facilitate diabetes education and management in patients with low literacy and numeracy skills. Diabetes Educ (2009) 35(2):233–45. doi:10.1177/0145721709331945

9. Schillinger D, Grumbach K, Piette J, Wang F, Osmond D, Daher C, et al. Association of health literacy with diabetes outcomes. JAMA (2002) 288(4):475–82. doi:10.1001/jama.288.4.475

10. Brown AF, Gregg EW, Stevens MR, Karter AJ, Weinberger M, Safford MM, et al. Race, ethnicity, socioeconomic position, and quality of care for adults with diabetes enrolled in managed care the Translating Research Into Action for Diabetes (TRIAD) study. Diabetes Care (2005) 28(12):2864–70. doi:10.2337/diacare.28.12.2864

11. Linden K. Voeding bij diabetes mellitus: Dieetbegeleiding van Turkse, Marokkaanse en Hindoestaanse bevolkingsgroepen. Bohn Stafleu van Loghum (2015).

12. Jansen J. Tijd Voor Gezond Gedrag: Bevordering Gezond Gedrag Specifieke Groepen. Utrecht: Bohn Stafleu van Loghum (2002).

13. Nierkens V, De Vries H, Stronks K. Smoking in immigrants: do socioeconomic gradients follow the pattern expected from the tobacco epidemic? Tob Control (2006) 15(5):385–91. doi:10.1136/tc.2006.014902

14. Van der Lucht F, Polder J. Towards Better Health: The Dutch 2010 Public Health Status and Forecasts Report. (2011). RIVM rapport 270061011.

15. Hosper K, Nierkens V, Nicolaou M, Stronks K. Behavioural risk factors in two generations of non-Western migrants: do trends converge towards the host population? Eur J Epidemiol (2007) 22(3):163–72. doi:10.1007/s10654-007-9104-7

16. Hoeymans N, Loon JV, Achterberg P, Berg Mvd, Harbers M, Hertog Fd, et al. Volksgezondheid Toekomst Verkenning 2014 (VTV-2014). Bilthoven: Trends in Volksgezondheid (2014). Available from: http://www.eengezondernederland.nl/Een_gezonder_Nederland/Highlights/Trends_in_de_volksgezondheid

17. van der Heide I, Uiters E, Rademakers J, Struijs JN, Schuit AJ, Baan CA. Associations among health literacy, diabetes knowledge, and self-management behavior in adults with diabetes: results of a Dutch cross-sectional study. J Health Commun (2014) 19(sup 2):115–31. doi:10.1080/10810730.2014.936989

18. Lanting LC, Joung IM, Vogel I, Bootsma AH, Lamberts SW, Mackenbach JP. Ethnic differences in outcomes of diabetes care and the role of self-management behavior. Patient Educ Couns (2008) 72(1):146–54. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2008.03.008

19. Schillinger D, Bindman A, Wang F, Stewart A, Piette J. Functional health literacy and the quality of physician-patient communication among diabetes patients. Patient Educ Couns (2004) 52(3):315–23. doi:10.1016/S0738-3991(03)00107-1

20. Sudore RL, Mehta KM, Simonsick EM, Harris TB, Newman AB, Satterfield S, et al. Limited literacy in older people and disparities in health and healthcare access. J Am Geriatr Soc (2006) 54(5):770–6. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00691.x

21. Kohinor MJ, Stronks K, Nicolaou M, Haafkens JA. Considerations affecting dietary behaviour of immigrants with type 2 diabetes: a qualitative study among Surinamese in the Netherlands. Ethn Health (2011) 16(3):245–58. doi:10.1080/13557858.2011.563557

22. Gallant MP. The influence of social support on chronic illness self-management: a review and directions for research. Health Educ Behav (2003) 30(2):170–95. doi:10.1177/1090198102251030

23. Glanz K, Rimer BK, Viswanath K. Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research, and Practice. 4th ed. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass (2008).

24. Riley KM, Glasgow RE, Eakin EG. Resources for health: a social-ecological intervention for supporting self-management of chronic conditions. J Health Psychol (2001) 6(6):693–705. doi:10.1177/135910530100600607

25. Tillotson LM, Smith MS. Locus of control, social support, and adherence to the diabetes regimen. Diabetes Educ (1996) 22(2):133–9. doi:10.1177/014572179602200206

27. Lawrence W, Skinner C, Haslam C, Robinson S, Inskip H, Barker D, et al. Why women of lower educational attainment struggle to make healthier food choices: the importance of psychological and social factors. Psychol Health (2009) 24(9):1003–20. doi:10.1080/08870440802460426

28. Eakin EG, Bull SS, Glasgow RE, Mason M. Reaching those most in need: a review of diabetes self-management interventions in disadvantaged populations. Diabetes Metab Res Rev (2002) 18(1):26–35. doi:10.1002/dmrr.266

29. Kim E-H, Stolyar A, Lober WB, Herbaugh AL, Shinstrom SE, Zierler BK, et al. Challenges to using an electronic personal health record by a low-income elderly population. J Med Internet Res (2009) 11(4):e44. doi:10.2196/jmir.1256

30. Lober WB, Zierler B, Herbaugh A, Shinstrom SE, Stolyar A, Kim E-H, et al. Barriers to the use of a personal health record by an elderly population. AMIA Annual Symposium Proceedings. American Medical Informatics Association (2006).

31. Bartholomew LK, Parcel GS, Kok G, Gottlieb NH. Intervention Mapping. Designing Theory and Evidence Based Health Promotion Programs. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass (2006).

32. Vissenberg C, Nierkens V, Uitewaal PJ, Geraci D, Middelkoop BJ, Nijpels G, et al. The DISC (Diabetes in Social Context) Study-evaluation of a culturally sensitive social network intervention for diabetic patients in lower socioeconomic groups: a study protocol. BMC Public Health (2012) 12(199):11. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-12-199

33. Vissenberg C, Stronks K, Nijpels G, Uitewaal PJM, Middelkoop BJC, Kohinor MJE, et al. The impact of a social network based intervention promoting diabetes self-management in socioeconomically deprived patients: a qualitative evaluation of the intervention strategies. BMJ Open (2016) 6(4):e010254. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010254

34. Vissenberg C, Nierkens V, Uitewaal PJ, Middelkoop BJ, Stronks K. Recruitment and retention in a 10-month social network-based intervention promoting diabetes self-management in socioeconomically deprived patients: a qualitative process evaluation. BMJ Open (2017) 7(7):e012284. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012284

35. Eldredge LKB, Markham CM, Ruiter RA, Kok G, Parcel GS. Planning Health Promotion Programs: An Intervention Mapping Approach. John Wiley & Sons (2016).

37. Bandura A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action. A Social Cognitive Theory. US: Prentice-Hall, Inc (1986).

38. Marlatt GA, Donovan DM. Relapse Prevention. Maintenance Strategies in the Treatment of Addictive Behaviors. New York; London: The Guilford Press (2005).

40. Clark NM. Management of chronic disease by patients. Annu Rev Public Health (2003) 24(1):289–313. doi:10.1146/annurev.publhealth.24.100901.141021

41. Gale NK, Heath G, Cameron E, Rashid S, Redwood S. Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Med Res Methodol (2013) 13(1):117. doi:10.1186/1471-2288-13-117

42. Kohinor MJ, Stronks K, Haafkens JA. Factors affecting the disclosure of diabetes by ethnic minority patients: a qualitative study among Surinamese in the Netherlands. BMC Public Health (2011) 11(1):1. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-11-399

43. Fransen MP, Beune EJ, Baim-Lance AM, Bruessing RC, Essink-Bot M-L. Diabeteszelfmanagementondersteuning van patiënten met lage gezondheidsvaardigheden. Nederlands Tijdschrift voor Evid Based Pract (2015) 13(2):8–11. doi:10.1007/s12468-015-0014-5

44. Schuster J, Beune E, Stronks K. Metaphorical constructions of hypertension among three ethnic groups in the Netherlands. Ethn Health (2011) 16(6):583–600. doi:10.1080/13557858.2011.594996

45. Jansen Y, Uitewaal P, Wijsman-Grootendorst A, Geelhoed-Duijvestijn P. Sociale en culturele problemen bij het opvolgen van leefstijladviezen door allochtone diabetici [Social and cultural problems in the compliance with lifestyle advice by immigrant diabetics]. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd (2011) 155:A3117.