- 1Inserm, U1144, Paris, France

- 2Université Paris Descartes, UMR-S 1144, Paris, France

- 3Université Paris Diderot, Sorbonne Paris Cité, UMR-S 1144, Paris, France

- 4AP-HP, GH Saint-Louis–Lariboisière–F. Widal, Pôle de Psychiatrie et de Médecine Addictologique, Paris, France

Background: The use of light for its antidepressant action dates back to the beginnings of civilization. Three decades ago, the use of bright-light therapy (BLT) for treating Seasonal Affective Disorder (SAD) was officially proposed. Since then, a growing scientific literature reports its antidepressant efficacy in both unipolar and bipolar disorders (BD), with or without seasonal patterns. This review aims to examine the management of BLT as a personalized and precision treatment in SAD, unipolar, and BD.

Methods: We conducted a narrative review using Medline and Google Scholar databases up to June 2018.

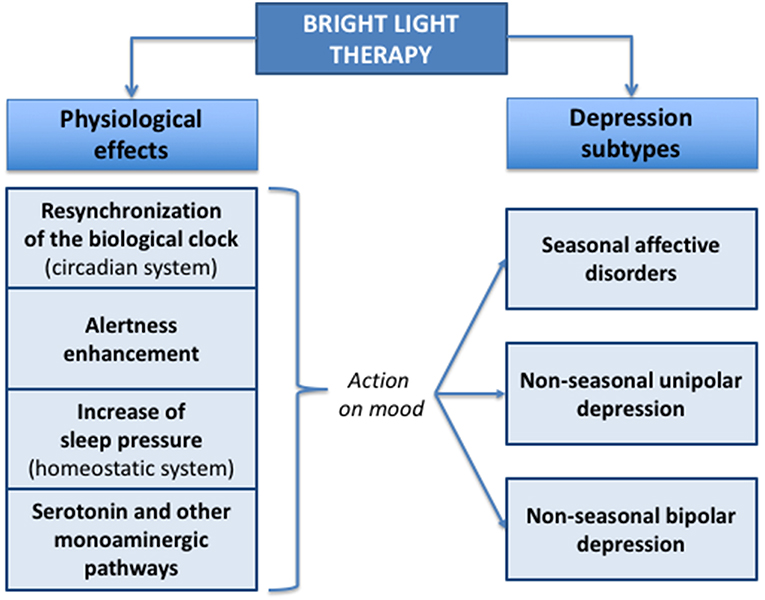

Results: BLT has physiological effects by resynchronizing the biological clock (circadian system), enhancing alertness, increasing sleep pressure (homeostatic system), and acting on serotonin, and other monoaminergic pathways. Effects of BLT on mood depend on several factors such as light intensity, wavelength spectrum, illumination duration, time of the day, and individual circadian rhythms. A growing body of evidence has been generated over the last decade about BLT evolving as an effective depression treatment not only to be used in SAD, but also in non-seasonal depression, with efficiency comparable to fluoxetine, and possibly more robust in patients with BD. The antidepressant action of BLT is fast (within 1-week) and safe, with the need in BD to protect against manic switch with mood stabilizers. Side effects might be nausea, diarrhea, headache, and eye irritation, and are generally mild and rare. This good safety profile may be of particular interest, especially in women during the perinatal period or for the elderly. The management of BLT needs to be clarified across mood disorders and future studies are expected to compare different dose-titration protocols, to validate its use as a maintenance treatment, and also to identify predictive biomarkers of response and tolerability. We propose clinical guidelines for BLT use in SAD, non-seasonal depression, and BD.

Conclusions : BLT is an efficient antidepressant strategy in mono- or adjunct-therapy, that should be personalized according the unipolar or bipolar subtype, the presence or absence of seasonal patterns, and also regarding its efficacy and tolerability.

Introduction

The use of light for its antidepressant action dates back to the beginnings of civilization (1). Three decades ago, the use of bright-light therapy (BLT) for treating Seasonal Affective Disorder (SAD) was officially proposed. It is now acknowledged as an antidepressant strategy for mood disorders (2–4). In the 1980s, BLT was developed in SAD to extend daytime photoperiod and counteract winter darkness (5). BLT is now considered to be the first line treatment for SAD in therapeutic guidelines (2). Since then, a growing scientific literature reports its antidepressant efficacy in both unipolar and bipolar disorders (BD), without such seasonal patterns. Indeed, the sustained antidepressant efficacy of BLT, used alone or in combination with antidepressant drugs–but also with some mood stabilizers and sleep deprivation, has been evidenced in numerous clinical studies (2, 6, 7). This antidepressant effect may be both due to light's effect on the biological clock -by phase advance and alignment of circadian rhythms- and/or actions on non-circadian pathways (8). Indeed, light modulates the activation of efferent serotonergic neurons, decreases the serotonin reuptake transporter (5-HTT) levels, and increases serotonin (5-HT) levels in mood regulatory areas such as the anterior cingulate and prefrontal Cortex (1, 9). Recent reviews discuss how light may influence mood, and emphasize recent finding of light's direct effects on enhancing alertness and the sleep homeostasis (10). Thus, light exerts strong effects on mood thanks to many circadian and non-circadian actions that may combine: phase shifting of circadian rhythms, enhancement alertness, sleep homeostasis by increasing EEG delta activity and sleep pressure, and modulation of the serotonin and other monoaminergic pathways. These effects of BLT on mood depend on several factors such as light intensity, wavelength spectrum, illumination duration, time of the day, and individual circadian rhythms (3).

However, the management of BLT continues to be a point of debate in mood disorders, with no evidence-based guidelines for implementing BLT in patients across mood disorders (2, 11, 12). This review aims to examine the management of BLT as a personalized and precision mood disorders treatment, encompassing both unipolar and bipolar disorders, and seasonal and non-seasonal characteristics.

Materials and Methods

Search Strategy

We aimed to consider papers examining efficacy of BLT in mood disorder including SAD, unipolar and bipolar disorders, with or without seasonal characteristics. Only data published in English and French were included in this review. We conducted a narrative review using Medline and Google Scholar databases up to June 2018, using the following keywords combination: (“depression” or “bipolar disorder” or “unipolar disorder,” or “seasonal affective disorder”) and (“light therapy” or “phototherapy”).

Study Selection

Two authors (JM, PAG) reviewed the title and abstract of identified publications in order to identify eligible studies. The two resulting article lists were compared and, in case of disagreement, the final decision as to inclusion was made by consensus. JM and PG independently and then jointly selected studies for detailed extraction of information, mostly based on the full text. In cases where full text was not available, corresponding authors were contacted. If a reply was not obtained following a 6-month waiting period, abstracts were then considered in the review only if the appropriate information was included. The exclusion criteria included reviews, meta-analyses, commentaries, case reports, and studies where bright light therapy on patients with BD or SAD or unipolar depression was not investigated. Finally, we decided to divide literature results in four main sections: (1) BLT in SAD; (2) BLT in non-seasonal depression; (3) BLT in BD depression; (4) BLT for sleep and circadian rhythms abnormalities associated in chronic mood disorders.

Results

The literature search returned 234 records pertaining to BLT, SAD, and unipolar and bipolar disorders, with or without seasonal characteristics. Following preliminary screening of the titles and abstracts, 125 records were excluded (reviews, meta-analyses, commentaries, case reports, and studies where bright light therapy on patients with BD or SAD or unipolar depression was not investigated). With 41 studies identified from the related articles function of the PubMed database and the reference list of retained studies, 84 independent studies were retained in the qualitative analysis. These investigations were classified according to their studied parameters: (1) 17 Studies explored BLT in SAD; (2) 40 studies explored BLT in non-seasonal depression; (3) 12 studies explored BLT in BD depression; (4) 15 studies explored BLT for sleep and circadian rhythms abnormalities associated in chronic mood disorders.

Bright Light Therapy in Seasonal Affective Disorders (SAD)

BLT as an Effective Curative Treatment in SAD

Among mood disorders, seasonal affective disorder (SAD) corresponds to the seasonal pattern of recurrent major depressive episodes occurring during the same time of the year, usually in autumn or winter with spontaneous remission in the spring or summer (5). This disorder is frequent, with prevalence varying between 0.4 and 16% in the general population according to latitude, age, sex, and the method of measurement used (13). SAD is a severe transdiagnostic disorder that may affect patients with both unipolar and bipolar disorders (5, 14). Over the past two decades, researchers, and clinicians have mainly focused on the pathophysiological mechanisms involved in SAD. Studies support the existence of interactions between a genetic vulnerability and chronobiological factors, and brain process alterations including noradrenergic and serotoninergic neurotransmissions (8). Several international therapeutic guidelines and many studies suggest that BLT is a non-pharmacological antidepressant that has proved to be effective in SAD and is now used as the first line treatment for individuals with SAD because of its low side effects profile and high response rate about 67% in patients with milder SAD and 40% in severe SAD patients (2–4, 15–17).

Usage in SAD

BLT is classically delivered through a light box that is equipped with fluorescent tubes and a reflector or diffusing screen. Patients sit in front of the light box mounted on a table with their eyes open. BLT may be also administered thanks to light glasses or visors (18, 19).

Treatment in SAD may begin with exposition duration of 30 min, using a light intensity of 10,000 lux. Early morning administration offers greater chances for remission (20, 21). Measured at eye level, a therapeutic distance of 60–80 cm from the light box can be seen as standard requirements (some other devices recommend a distance of 30 cm, so we advise to follow the device recommendations that take into account light parameters and distance). Lower intensities also appear to be effective, but need longer exposure durations: 2,500 Lux for 2 h/day, 5,000 Lux for 1 h/day. Significant effects appear only at 2–3 weeks of treatment. Treatment is usually continued until the time of usual spontaneous remission in the spring or summer because the effects of LT do not persist after discontinuation of BLT. In addition, it has been observed that low-intensity blue-enriched light has a therapeutic effect comparable to standard bright light (10,000 lux) in treating SAD (22). Finally, BLT is well-tolerated by patients; adverse effects such as headache, eyestrain, nausea and agitation, are usually transient and mild (23, 24). Main contraindications are ophthalmic disorders (cataract, macular degeneration, glaucoma, retinitis pigmentosa) and disorders affecting the retina (retinopathy, diabetes, herpes, etc.); and patients at risk (or if there is a doubt) should have pretreatment ophthalmological examinations (3).

BLT as a Preventive Device for Seasonal Affective Disorder

Patients with SAD might benefit from prophylactic use of BLT (25, 26). A recent Cochrane review assessed the efficacy of BLT in preventing SAD (27). Both forms of preventive light therapy (light boxes and visor) reduced the incidence of SAD compared with no light therapy. Although not statistically significant, they observed that BLT reduced the risk of SAD incidence of 36% (27). However, given methodological limitations (small sample sizes of available RCTs, and lack of power for some analyses), authors concluded that the decision for or against initiating preventive treatment of SAD and the treatment selected should be strongly based on patient preferences.

Bright Light Therapy for Non-seasonal Depression

BLT as an Effective Treatment in Non-seasonal Depression

In the last two decades, the interest in BLT has expanded far beyond SAD. Indeed, several studies investigated the efficacy of BLT in treating non-seasonal depression disorders as alternative or adjunctive treatment. This is of major interest because depression affects an estimated 350 million people worldwide and is projected to become the second global leading cause of disability by the year 2020 (28). Moreover, only 50–60% of patients respond to first line antidepressants and only 35–40% experience remission of symptoms (29). Last but not least, pharmacological antidepressant strategies as first line treatments take at least 4 weeks to build up its effect and work fully (11).

Recent systematic reviews and meta-analyses confirmed this extent of antidepressant efficacy in non-seasonal depressions. Indeed the APA Committee on Research on Psychiatric treatment (2) and a Cochrane review (12) observed significant effect sizes equivalent to those in most antidepressant pharmacotherapy trials that were about 0.84. Reports and double blind placebo controlled studies suggest that the efficacy of BLT as an adjunct therapy in treating non-seasonal depression in its initial phase is faster and is perceived during the first week of treatment (7, 30, 31). These studies also confirmed the efficacy of the combination of BLT and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) with benefit after 1 month of treatment. BLT combined with SSRI lead to a faster (within a week) and better remission of patients (by reducing 30% of symptoms) in patients with non-seasonal depression than SSRIs alone (7, 31). In line with this, results are confirmed in a recent meta-analysis that also conclude that BLT are effective for patients with non-seasonal depression with clinical significant effect (SMD = −0.62, P < 0.001, I2 = 37%) and can be a helpful additional treatment for depression (32). This meta-analysis included 419 patients with non-seasonal depression (unipolar or bipolar depression) from 9 trials: 211 receiving BLT and 208-placebo controls. Most participants received BLT as a monotherapy except in two trials where they had BLT in addition to antidepressant. First, their results reported significant effects in the first week when administered in the early morning (2, 12). They found the largest antidepressant effect of BLT for an exposure duration of 2–5 weeks, and unfortunately were not able to propose an optimal intensity of BLT given the heterogeneity of the trials. Another recent meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (11), including 881 participants from 20 RCTs used BLT as monotherapy compared to an inactive placebo/control group; and also as an adjunctive treatment in comparison to the same control group. They considered individuals with all depression subtypes excepting SAD: major depressive disorder; persistent depressive disorder, and BD depression. All forms of BLT (timing of administration, brightness, and duration of light exposure) were included, even though most studies (n = 5) used bright white light at 10,000 lux in early morning for 30 min/day or 2,500 lux for 120 min/day. They found that BLT was associated with a small to moderate effect in reducing symptoms in adults (11). Interestingly, studies demonstrated twice the reduction in depressive symptoms for BLT than placebo. Moreover, meta-analyses of Perera et al. (11) and Golden et al. (2) both found that BLT may be most effective when applied as an antidepressant monotherapy (and not as an adjunct treatment), when administered in the morning and among out-patients, that may have less severe depressive symptoms and comorbidities than in-patients. So, taken as a whole, patients who are non-responsive or ineligible for pharmacotherapy may benefit from monotherapy BLT, but BLT could also be considered as an effective first line treatment. For the elderly, BLT also seems to be efficient (33–35). Recently a systematic review in non-seasonal geriatric depression found that BLT during 6 weeks, with exposure duration varying between 30 and 60 min and light intensity varying from 1,200 to 10,000 Lux, is an effective treatment for reducing the depression symptoms in the elderly (34).

Finally, regarding safety in non-seasonal depression, side effects are rare and generally mild: nausea, diarrhea, headache, and eye irritation (11). This good safety profile may be of particular interest for women with depression in the perinatal period where medications may be inappropriate or ineffective, and also in the elderly.

Usage in Non-seasonal Depression

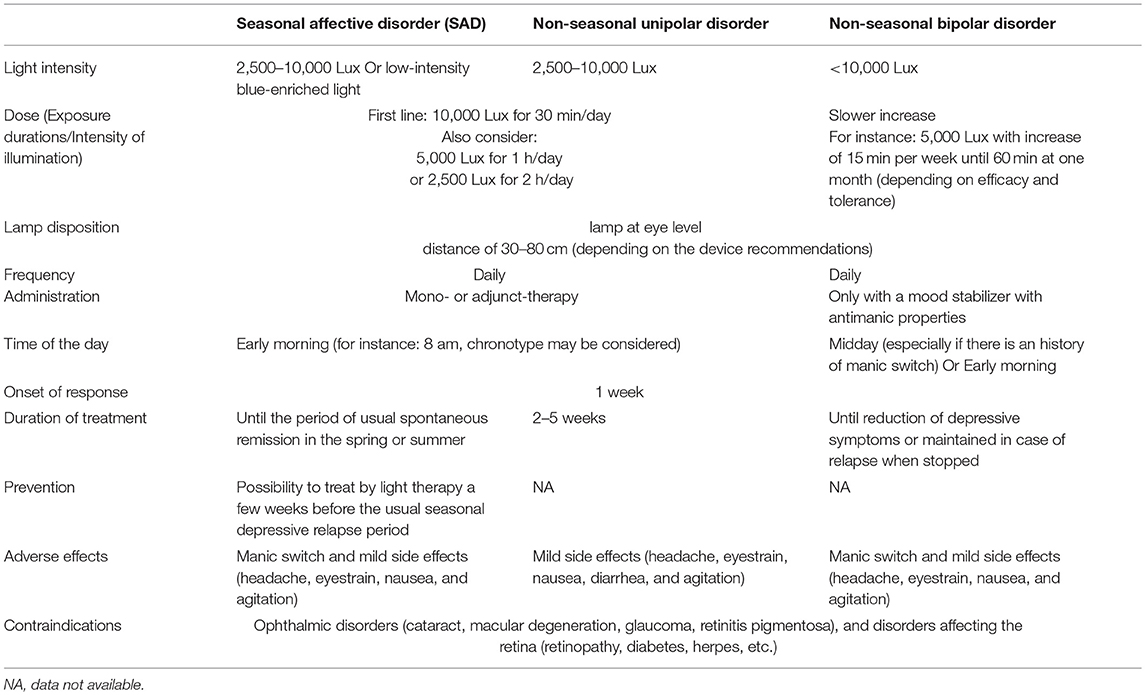

Precise recommendations regarding the optimal treatment (i.e., optimal exposure duration and intensity) are difficult because of the heterogeneity of study protocols and absence of comparisions between protocols (32). However, it is possible to say that BLT is confirmed to be efficient both as a mono- or adjunct-therapy in treating non-seasonal depression in his acute phase, with benefits that can be perceived during the first week of treatment. The effects of BLT do not appear to persist after discontinuation with a complete offset of effect after 1 month (36), and this relapse can be prevented when combining BLT with common antidepressant drugs (37). According to previous studies, daily early morning exposures to 2,500 Lux for 2 h (38), 5,000 Lux for 1 h (39), or 10,000 Lux for 30 min (40) all appear efficient in reducing antidepressant symptoms. Finally, BLT is well-tolerated by patients, and possible adverse effects might be headache, eyestrain, nausea, and agitation, that are usually transient and mild (see Table 1).

Bright Light Therapy in Acute Bipolar Disorder Depression

BLT as an Effective Treatment in Bipolar Disorder Depression

About 1–4% of the worldwide population suffers from bipolar disorder (BD), which is a severe mental disorder associated with both depressive and manic episodes that may be induced by antidepressants (41, 42). Given the limited treatment options in BD depression, since Lewy's study (43) several researches have focused on investigating BLT in this particular population because BD are increasingly recognized as disorders of the biological clock (44, 45), with circadian dysregulation being evident in both acute and remission phases (46, 47). Indeed, research has shown that patients with BD depression responded robustly to BLT (1). While the efficacy of BLT in monotherapy is non-significant in some studies (48, 49), the combination of BLT with other chronotherapeutic techniques such as sleep deprivation and with lithium salts was proven in BD depression patients (6, 50).

First, Leibenluft et al. showed that BLT at midday could be tailored to counteract depressive swings without exacerbating mania, in course of rapid cycling BD (51). Later, Benedetti et al. showed that morning sunlight reduces length of hospitalization in BD depression by comparing a sample of 415 unipolar and 187 bipolar depression inpatients assigned with eastern or western windows (52). They found that inpatients in eastern rooms exposed to direct sunlight in the morning had a shorter hospitalization than patients in western rooms (52). In 2005, the same team showed that combination of total sleep deprivation and BLT in drug-resistant patients with BD depression was useful in triggering an acute response (6). Since 2005, several randomized controlled studies and meta-analyses of randomized controlled studies focused on BLT efficacy in BD and confirmed that BLT is an effective and safe option as an adjunctive therapy in BD depression (53–56). Indeed, Yorguner Kupeli et al. confirmed in a randomized single blind placebo-controlled study the efficacy of BLT as an add-on treatment for BD depression when it is administered in the mornings at 10,000 lux for 30 min for a 2-week period, sitting 40–70 cm's away from the device (56). Zhou et al. also confirmed in a randomized single blind placebo controlled study the efficacy of 1 h, 5,000 lux, every morning -between 6:30 am and 9 am- of BLT as an add-on therapy, by reduction of depressive symptoms and observed onset efficacy at 4 days (54). Interestingly, no participants experienced symptoms of mania and no serious adverse effects were reported. Regarding midday BLT, Sit et al. performed a 6 week randomized double–blind placebo-controlled trial and found results supporting midday BLT as an efficient therapy in BD depression (55). In this RCT study, light therapy was administered as an add-on therapy (anti-manic or antidepressant medication) to patients with a current moderate or severe depression and showed that the BLT group (7,000 Lux at midday) had significantly higher remission rates (56%) vs. the 50-lux dim red light (14.3%). Duration of light therapy was increased progressively every week by 15 min to attain a target dose of 60 min per day at 4 weeks (55). Again, in this randomized controlled trial, no hypomanic/manic shift was observed, contrary to a previous report from the same team that observed (hypo)manic switches in females with rapid cycling BD and morning exposures (55). Benedetti (57) performed a systematic review of the literature studies reporting effect of antidepressant BLT in BD and their conclusions were limited again by the heterogeneity of treatment modalities between studies. Nevertheless, their review managed to include 799 treated patients and shows that the rate of switch into mania after morning BLT was small and close to the 4.2% expected during the placebo treatment of BD, whereas the rate of switch into mania after antidepressant drug treatment is 15–40% (58).

Usage in Bipolar Depression

BLT is a robust strategy treatment for bipolar depression and might be considered as a first line option for depressive episode in the course of BD (Table 1). Interestingly, BLT acts rapidly (within 4 days), has low side effects and low risk of manic switch in combination with mood stabilizing treatment (54). The most efficient light parameters are not yet fully determined, but it seems that patients are sensitive to light intensities below 10,000 lux, depending on the duration of exposure. Some observations suggest that depression could respond to light intensities as low as 300–500 lux (48, 50). Studies support both midday or morning BLT as an efficient therapy in BD depression and duration of light therapy could be increased progressively every week by 15 min to attain a target dose of 60 min per daily at 4 weeks (55). Furthermore, BLT should always be combined with a mood stabilizer, first to prevent manic switch in BD, but also to enhance and sustain the acute antidepressant effects of BLT (6).

BLT for Sleep and Circadian Rhythm Abnormalities in Chronic Mood Disorders

BLT as an Effective Treatment in sleep and Circadian Rhythms Abnormalities

Light may act as a therapeutic mood stabilizer in patients with mood disorders during remission by stabilizing sleep alterations (like insomnia or longer sleep duration), and circadian rhythms (like evening chronotype or sleep phase delayed) (10). Indeed light exerts strong effects on mood through different pathways. First, light may affect mood through phase shifting of circadian rhythms (59–61). This circadian effect of light on mood results from its effect on the optimal alignment vs. misalignment of different circadian rhythms, which may be mediated through the phase shifting effects of light and modifying the duration of nocturnal melatonin secretion (59–61). This effect of light on mood via the circadian system is well-illustrated by SAD. SAD involves an internal misalignment of the circadian system and responds positively to treatments that resynchronize the biological clock, such as BLT. So, in addition to increasing the monoaminergic tone, application of BLT in the morning causes phase advance of endogenous circadian rhythms. These effects of light exposure on mood via modulation of the circadian system are not restricted to patients with SAD, but also in non-seasonal depression (both unipolar and bipolar), with available data that shows that BLT is an effective antidepressant or mood stabilizer (6).

Secondly, light exerts an effect on alertness, a parameter-influencing mood (62, 63). Impaired alertness is a common symptom in many affective disorders such as MDD, BD, or SAD (10). Increasing alertness has also been an effective strategy for improving mood (64–66). Light stimulates alertness through the synchronization of the homeostatic and circadian drives, and through melatonin suppression (10). And light has direct effect on alertness via the melanopsin retinal ganglion cells by impinging on the sleep-active neurons: through simultaneous inhibition of the sleep-inducing VLPO and activation of the monoaminergic arousal systems that are also involved in control of mood (10).

Thirdly, light may regulate mood disorders by improving sleep homeostasis with direct positive effect on the EEG delta sleep activity via the secretion of melanopsin, which is a photopigment expressed in a subset of retinal ganglion cells that activates the VLPO and improve by this way sleep homeostasis (10, 67, 68). This is again well-illustrated in studies with SAD patients that have a lower delta activity and lower sleep efficiency (69). Indeed, sleep deprivation combined with chronotherapeutics such as BLT have an antidepressant effect by improving sleep pressure (69).

All these data support an impact of BLT by resynchronizing the biological clock (circadian system), and/or enhancing alertness, and/or increasing sleep pressure (homeostatic system), acting consequently on mood both in acute and remission phases (Figure 1).

Recommendations for Use in Patients With BD in Remission

Sleep and circadian rhythm abnormalities are frequent in mood disorders, even between acute episodes, contributing to poor functioning, and relapses (70, 71). For instance, in BD, studies of actigraphy and DMLO identify higher prevalence of delayed sleep phase (72) and exhibit greater variability in sleep duration, fragmentation, later, and more variable bedtimes than healthy controls (71). In this context, we suggest treating and applying recommendations for comorbid delayed phase sleep, insomnia, or hypersomnia in individuals suffering from mood disorders, even in remission. Recommending BLT in the context of such circadian and sleep comorbidities in mood disorders may thus be similar to recommendations for previous different subtype of depression detailed previously (Table 1).

Discussion

This review draws up an inventory of scientific knowledge about the use of BLT in mood disorders thanks to a growing evidence about BLT evolving as an effective depression treatment not only to be used in SAD but also in non-seasonal depression and in BD. BLT is efficient on depression, acts rapidly, with low rates of manic switch, and can be easily prescribed combined or not with mood-stabilizing antidepressant, or other chronotherapeutic treatments such as sleep deprivation or lithium (6, 73). Table 1 summarizes different forms of BLT use in the different mood disorders subtypes. This review also highlights several shortcomings in the scientific literature, and paves the way for further studies to clarify the management of BLT across mood disorders by comparing different initiation protocols depending on depression subtypes, to validate its use as a maintenance treatment, and also to identify predictive biomarkers of response and tolerability.

First, there is a great heterogeneity of management of BLT across studies making it difficult to make recommendations for good practices of BLT (2, 11). For instance, whereas recent studies such as Lam et al. (40) that directly compared mono or adjunct therapies found larger effect of BLT/SSRI combination, some meta-analyses suggest on the other hand that monotherapy may be more effective (2, 11), maybe because of limitations previously advocated.

Secondly, where the lamp should be placed relative to the eye varies between available devices and across studies. Nevertheless, for most traditional BLT devices, it should be placed at eye level and at distance of 30–80 cm, in an adequately lighted room (where a newspaper may be read easily). The distance depends of the device and should be closely respected since Lux decreased quickly. Others new BLT devices should be placed as glasses and are easy to placed.

Thirdly, the vast majority of data are from review or meta-analyses in which the distinction is not made between unipolar disorder or BD, but also between seasonal characteristics or not, mostly because of lacking data and small sample sizes (55).

Nevertheless, our review aimed to propose global therapeutic strategies to use BLT in SAD, unipolar and bipolar disorders without seasonal characteristic and so, allows only partially personalizing BLT in mood disorder.

Because of the heterogeneity of study protocols and absence of comparisions between protocols, proper guidelines are difficult to define. In this context of absence of comparisons between protocols, we propose in BD to increase more slowly duration of exposure by 15 min every week to attain a target dose of 60 min per day at 4 weeks in case of insufficient response. In BD, a midday exposure might be safer with regards to manic switch, and should be preferred in cases where individuals have a history of antidepressant manic switch (74). BLT studies do not propose personalized BLT use modalities for bipolar disorder with seasonal pattern. For instance BLT studies assess only the effects of bright light therapy on SAD, which is a transdiagnostic disorder that may affect patients with unipolar and bipolar disorders, and proposed early morning administration with exposure duration of 30 min, using a light intensity of 10,000 lux.

Future studies will likely need to distinguish the use of BLT between bipolar disorder with seasonal pattern and unipolar disorder with seasonal pattern because patients with bipolar disorder with seasonal pattern are able to switch into mania (75). As patients with bipolar disorder without seasonal pattern, they are likely to need a midday utilization of BLT or a more progressive titration, and always in combination with an anti-manic treatment (75).

Finally, evidence suggests that light may play a role in the mood stabilizers therapeutic action by improving sleep quality, and stabilizing circadian rhythms (76). The role of sleep or circadian disturbances as disease course modifiers is well-established, mainly due to their association with treatment-refractory or prolonged mood phases and as predictors of early relapse (70). This review highlights the urgent need for good quality RCTs of BLT in BD during remission for relapses prevention through a potential improvement of sleep quality and stabilization of circadian rhythms.

Conclusion

BLT should be considered as a stand-alone treatment option in patient with SAD, but also non-seasonal unipolar or bipolar depression. BLT in treating mood disorders is characterized by rapid and sustained effects both in mono- or adjunct-therapy, combined with antidepressant, or mood stabilizing drugs. However, the management of BLT needs to be clarified across mood disorders and future studies are expected to compare different dose-titration protocols, to validate its use as a maintenance treatment, and also to identify predictive biomarkers of response and tolerance. Finally, BLT may also be useful to improve sleep quality, decreased alertness, abnormalities in circadian rhythms such as sleep phase delay syndrome, that are frequently associated in mood disorders, in order to prevent mood early relapses and recurrences.

Author Contributions

JM and PAG performed the literature search and analysis, and both contributed in the manuscript's redaction. JM wrote the first draft of the manuscript. PAG made the figure and the table.

Conflict of Interest Statement

PG reports grants from Assistance Publique-Hôpitaux de Paris.

The remaining author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

1. Geoffroy PA, Schroder CM, Bourgin P. Light treatment in depression: an antique treatment with new insights. Sleep med rev. (2018) 40:218–9. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2018.03.002

2. Golden RN, Gaynes BN, Ekstrom RD, Hamer RM, Jacobsen FM, Suppes T, et al. The efficacy of light therapy in the treatment of mood disorders: a review and meta–analysis of the evidence. Am j psychiatry. (2005) 162:656–62. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.4.656

3. Terman M, Terman JS. Light therapy for seasonal and non-seasonal depression: efficacy, protocol, safety, and side effects. CNS spectr. (2005) 10:647–63; quiz 72. doi: 10.1017/S1092852900019611

4. Terman M. Evolving applications of light therapy. Sleep med rev. (2007) 11:497–507. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2007.06.003

5. Rosenthal NE, Sack DA, Gillin JC, Lewy AJ, Goodwin FK, Davenport Y, et al. Seasonal affective disorder. A description of the syndrome and preliminary findings with light therapy. Arch general psychiatry. (1984) 41:72–80. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1984.01790120076010

6. Benedetti F, Barbini B, Fulgosi MC, Colombo C, Dallaspezia S, Pontiggia A, et al. Combined total sleep deprivation and light therapy in the treatment of drug-resistant bipolar depression: acute response and long-term remission rates. J clin psychiatry. (2005) 66:1535–40. doi: 10.4088/JCP.v66n1207

7. Martiny K, Lunde M, Unden M, Dam H, Bech P. Adjunctive bright light in non-seasonal major depression: results from patient-reported symptom and well-being scales. Acta psychiatr Scand. (2005) 111:453–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2005.00532.x

8. Maruani J, Anderson G, Etain B, Lejoyeux M, Bellivier F, Geoffroy PA. The neurobiology of adaptation to seasons: relevance and correlations in bipolar disorders. Chronobiol int. (2018) 35:1335–53. doi: 10.1080/07420528.2018.1487975

9. Tyrer AE, Levitan RD, Houle S, Wilson AA, Nobrega JN, Meyer JH. Increased seasonal variation in serotonin transporter binding in seasonal affective disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology. (2016) 41:2447–54. doi: 10.1038/npp.2016.54

10. Stephenson KM, Schroder CM, Bertschy G, Bourgin P. Complex interaction of circadian and non-circadian effects of light on mood: shedding new light on an old story. Sleep med rev. (2012) 16:445–54. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2011.09.002

11. Perera S, Eisen R, Bhatt M, Bhatnagar N, de Souza R, Thabane L, et al. Light therapy for non-seasonal depression: systematic review and meta-analysis. BJPsych open. (2016) 2:116–26. doi: 10.1192/bjpo.bp.115.001610

12. Tuunainen A, Kripke DF, Endo T. Light therapy for non-seasonal depression. Cochr database syst rev. (2004) 2:CD004050. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004050.pub2

13. Magnusson A. An overview of epidemiological studies on seasonal affective disorder. Acta psychiatr Scand. (2000) 101:176–84. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2000.101003176.x

14. Geoffroy PA, Bellivier F, Scott J, Etain B. Seasonality and bipolar disorder: a systematic review, from admission rates to seasonality of symptoms. J affect disorders. (2014) 168:210–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.07.002

15. Terman M, Terman JS, Quitkin FM, McGrath PJ, Stewart JW, Rafferty B. Light therapy for seasonal affective disorder. A review of efficacy. Neuropsychopharmacology. (1989) 2:1–22. doi: 10.1016/0893-133X(89)90002-X

16. Ravindran AV, Balneaves LG, Faulkner G, Ortiz A, McIntosh D, Morehouse RL, et al. Canadian network for mood and anxiety treatments (CANMAT) 2016 clinical guidelines for the management of adults with major depressive disorder: section 5. Complementary and alternative medicine treatments. Can j psychiatry Revue canad psychiatr. (2016) 61:576–87. doi: 10.1177/0706743716660290

17. Lam RW, Levitt AJ, Levitan RD, Enns MW, Morehouse R, Michalak EE, et al. The Can-SAD study: a randomized controlled trial of the effectiveness of light therapy and fluoxetine in patients with winter seasonal affective disorder. Am j psychiatry. (2006) 163:805–12. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.5.805

18. Ravaris CL, Elliott B, Hegel M, Rose R, Schiffman J, Singer J. A simple portable ocular light device for phototherapy of seasonal affective disorder. Biomed instrument technol. (1994) 28:484–9.

19. Bragard I, Coucke PA. [Impact of the use of Luminette(R) on well-being at work in a radiotherapy department]. Cancer radiother. (2013) 17:731–5. doi: 10.1016/j.canrad.2013.05.014

20. Eastman CI, Young MA, Fogg LF, Liu L, Meaden PM. Bright light treatment of winter depression: a placebo-controlled trial. Arch general psychiatry. (1998) 55:883–9. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.10.883

21. Terman M, Terman JS, Ross DC. A controlled trial of timed bright light and negative air ionization for treatment of winter depression. Arch general psychiatry. (1998) 55:875–82. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.10.875

22. Meesters Y, Dekker V, Schlangen LJ, Bos EH, Ruiter MJ. Low-intensity blue-enriched white light (750 lux) and standard bright light (10,000 lux) are equally effective in treating SAD. A randomized controlled study. BMC psychiatry. (2011) 11:17. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-11-17

23. Terman M, Terman JS. Bright light therapy: side effects and benefits across the symptom spectrum. J clin psychiatry. (1999) 60:799–808; quiz 9. doi: 10.4088/JCP.v60n1113

24. Labbate LA, Lafer B, Thibault A, Sachs GS. Side effects induced by bright light treatment for seasonal affective disorder. J clin psychiatry. (1994) 55:189–91.

25. Partonen T, Lonnqvist J. Prevention of winter seasonal affective disorder by bright-light treatment. Psychol med. (1996) 26:1075–80. doi: 10.1017/S003329170003539X

26. Meesters Y, Beersma DG, Bouhuys AL, van den Hoofdakker RH. Prophylactic treatment of seasonal affective disorder (SAD) by using light visors: bright white or infrared light? Biol psychiatry. (1999) 46:239–46. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3223(98)00252-2

27. Nussbaumer B, Kaminski-Hartenthaler A, Forneris CA, Morgan LC, Sonis JH, Gaynes BN, et al. Light therapy for preventing seasonal affective disorder. Cochr database syst rev. (2015) 11:CD011269. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011269.pub2

28. Murray CJ, Lopez AD. Evidence-based health policy–lessons from the global burden of disease study. Science. (1996) 274:740–3. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5288.740

29. Connolly KR, Thase ME. If at first you don't succeed: a review of the evidence for antidepressant augmentation, combination and switching strategies. Drugs. (2011) 71:43–64. doi: 10.2165/11587620-000000000-00000

30. Kripke DF. Light treatment for non-seasonal depression: speed, efficacy, and combined treatment. J affect disorders. (1998) 49:109–17. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0327(98)00005-6

31. Benedetti F, Colombo C, Pontiggia A, Bernasconi A, Florita M, Smeraldi E. Morning light treatment hastens the antidepressant effect of citalopram: a placebo-controlled trial. J clin psychiatry. (2003) 64:648–53. doi: 10.4088/JCP.v64n0605

32. Al-Karawi D, Jubair L. Bright light therapy for non-seasonal depression: meta-analysis of clinical trials. J affect disorders. (2016) 198:64–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.03.016

33. Lieverse R, Van Someren EJ, Nielen MM, Uitdehaag BM, Smit JH, Hoogendijk WJ. Bright light treatment in elderly patients with non-seasonal major depressive disorder: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Arch general psychiatry. (2011) 68:61–70. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.183

34. Zhao X, Ma J, Wu S, Chi I, Bai Z. Light therapy for older patients with non-seasonal depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J affect disorders. (2018) 232:291–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2018.02.041

35. Sondergaard MP, Jarden JO, Martiny K, Andersen G, Bech P. Dose response to adjunctive light therapy in citalopram-treated patients with post-stroke depression. A randomised, double-blind pilot study. Psychother psychosomat. (2006) 75:244–8. doi: 10.1159/000092895

36. Martiny K, Lunde M, Unden M, Dam H, Bech P. The lack of sustained effect of bright light, after discontinuation, in non-seasonal major depression. Psychol med. (2006) 36:1247–52. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706008105

37. Martiny K. Adjunctive bright light in non-seasonal major depression. Acta psychiatr Scand Supplement. (2004) 110:7–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2004.00460_2.x

38. Kripke DF, Mullaney DJ, Klauber MR, Risch SC, Gillin JC. Controlled trial of bright light for non-seasonal major depressive disorders. Biol psychiatry. (1992) 31:119–34. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(92)90199-A

39. Even C, Schroder CM, Friedman S, Rouillon F. Efficacy of light therapy in non-seasonal depression: a systematic review. J affect disorders. (2008) 108:11–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2007.09.008

40. Lam RW, Levitt AJ, Levitan RD, Michalak EE, Cheung AH, Morehouse R, et al. Efficacy of bright light treatment, fluoxetine, and the combination in patients with non-seasonal major depressive disorder: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA psychiatry. (2016) 73:56–63. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.2235

41. Collins PY, Patel V, Joestl SS, March D, Insel TR, Daar AS, et al. Grand challenges in global mental health. Nature. (2011) 475:27–30. doi: 10.1038/475027a

42. Merikangas KR, Akiskal HS, Angst J, Greenberg PE, Hirschfeld RM, Petukhova M, et al. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of bipolar spectrum disorder in the national comorbidity survey replication. Arch general psychiatry. (2007) 64:543–52. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.5.543

43. Lewy AJ, Kern HA, Rosenthal NE, Wehr TA. Bright artificial light treatment of a manic-depressive patient with a seasonal mood cycle. Am j psychiatry. (1982) 139:1496–8. doi: 10.1176/ajp.139.11.1496

44. Harvey AG. Sleep and circadian rhythms in bipolar disorder: seeking synchrony, harmony, and regulation. Am j psychiatry. (2008) 165:820–9. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08010098

45. Gonzalez R. The relationship between bipolar disorder and biological rhythms. J clin psychiatry. (2014) 75:e323–31. doi: 10.4088/JCP.13r08507

46. Boudebesse C, Lajnef M, Geoffroy PA, Bellivier F, Nieto I, Gard S, et al. Chronotypes of bipolar patients in remission: validation of the French version of the circadian type inventory in the FACE-BD sample. Chronobiol int. (2013) 30:1042–9. doi: 10.3109/07420528.2013.798330

47. Geoffroy PA, Scott J, Boudebesse C, Lajnef M, Henry C, Leboyer M, et al. Reply: sleep in patients with remitted bipolar disorders: analyses stratified on actigraphy devices, age and gender. Acta psychiatr Scand. (2015) 131:400. doi: 10.1111/acps.12400

48. Deltito JA, Moline M, Pollak C, Martin LY, Maremmani I. Effects of phototherapy on non-seasonal unipolar and bipolar depressive spectrum disorders. J affect disorders. (1991) 23:231–7. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(91)90105-2

49. Dauphinais DR, Rosenthal JZ, Terman M, DiFebo HM, Tuggle C, Rosenthal NE. Controlled trial of safety and efficacy of bright light therapy vs. negative air ions in patients with bipolar depression. Psychiatry res. (2012) 196:57–61. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2012.01.015

50. Colombo C, Lucca A, Benedetti F, Barbini B, Campori E, Smeraldi E. Total sleep deprivation combined with lithium and light therapy in the treatment of bipolar depression: replication of main effects and interaction. Psychiatry res. (2000) 95:43–53. doi: 10.1016/S0165-1781(00)00164-5

51. Leibenluft E, Turner EH, Feldman-Naim S, Schwartz PJ, Wehr TA, Rosenthal NE. Light therapy in patients with rapid cycling bipolar disorder: preliminary results. Psychopharmacol bull. (1995) 31:705–10.

52. Benedetti F, Colombo C, Barbini B, Campori E, Smeraldi E. Morning sunlight reduces length of hospitalization in bipolar depression. J affect disorders. (2001) 62:221–3. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0327(00)00149-X

53. Tseng PT, Chen YW, Tu KY, Chung W, Wang HY, Wu CK, et al. Light therapy in the treatment of patients with bipolar depression: a meta–analytic study. Eur neuropsychopharmacol. (2016) 26:1037–47. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2016.03.001

54. Zhou TH, Dang WM, Ma YT, Hu CQ, Wang N, Zhang GY, et al. Clinical efficacy, onset time and safety of bright light therapy in acute bipolar depression as an adjunctive therapy: a randomized controlled trial. J affect disorders. (2018) 227:90–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2017.09.038

55. Sit DK, McGowan J, Wiltrout C, Diler RS, Dills JJ, Luther J, et al. Adjunctive bright light therapy for bipolar depression: a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Am j psychiatry. (2018) 175:131–9. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2017.16101200

56. Yorguner Kupeli N, Bulut NS, Carkaxhiu Bulut G, Kurt E, Kora K. Efficacy of bright light therapy in bipolar depression. Psychiatry res. (2017) 260:432–8. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2017.12.020

57. Benedetti F. Rate of switch from bipolar depression into mania after morning light therapy: a historical review. Psychiatry Res. (2018) 261:351–56. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2018.01.013

58. Goldberg JF. When do antidepressants worsen the course of bipolar disorder? J psychiatr pract. (2003) 9:181–94. doi: 10.1097/00131746-200305000-00002

59. Boivin DB, Czeisler CA, Dijk DJ, Duffy JF, Folkard S, Minors DS, et al. Complex interaction of the sleep-wake cycle and circadian phase modulates mood in healthy subjects. Arch general psychiatry. (1997) 54:145–52. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830140055010

60. Boivin DB. Influence of sleep-wake and circadian rhythm disturbances in psychiatric disorders. J psychiatry neurosci. (2000) 25:446–58.

61. Danilenko KV, Cajochen C, Wirz-Justice A. Is sleep per se a zeitgeber in humans? J biol rhythms. (2003) 18:170–8. doi: 10.1177/0748730403251732

62. Revell VL, Burgess HJ, Gazda CJ, Smith MR, Fogg LF, Eastman CI. Advancing human circadian rhythms with afternoon melatonin and morning intermittent bright light. J clin endocrinol metab. (2006) 91:54–9. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-1009

63. Lockley SW, Evans EE, Scheer FA, Brainard GC, Czeisler CA, Aeschbach D. Short-wavelength sensitivity for the direct effects of light on alertness, vigilance, and the waking electroencephalogram in humans. Sleep. (2006) 29:161–8. doi: 10.1093/sleep/29.2.161

64. Penetar D, McCann U, Thorne D, Kamimori G, Galinski C, Sing H, et al. Caffeine reversal of sleep deprivation effects on alertness and mood. Psychopharmacology. (1993) 112:359–65. doi: 10.1007/BF02244933

65. DeBattista C, Doghramji K, Menza MA, Rosenthal MH, Fieve RR, Modafinil in Depression Study G. Adjunct modafinil for the short-term treatment of fatigue and sleepiness in patients with major depressive disorder: a preliminary double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J clin psychiatry. (2003) 64:1057–64. doi: 10.4088/JCP.v64n0911

66. Even C, Thuile J, Santos J, Bourgin P. Modafinil as an adjunctive treatment to sleep deprivation in depression. J psychiatry neurosci. (2005) 30:432–3.

67. Tsai JW, Hannibal J, Hagiwara G, Colas D, Ruppert E, Ruby NF, et al. Melanopsin as a sleep modulator: circadian gating of the direct effects of light on sleep and altered sleep homeostasis in Opn4(-/-) mice. PLoS biol. (2009) 7:e1000125. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000125

68. Gaus SE, Strecker RE, Tate BA, Parker RA, Saper CB. Ventrolateral preoptic nucleus contains sleep-active, galaninergic neurons in multiple mammalian species. Neuroscience. (2002) 115:285–94. doi: 10.1016/S0306-4522(02)00308-1

69. Benedetti F, Barbini B, Colombo C, Smeraldi E. Chronotherapeutics in a psychiatric ward. Sleep med rev. (2007) 11:509–22. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2007.06.004

70. Bellivier F, Geoffroy PA, Etain B, Scott J. Sleep- and circadian rhythm-associated pathways as therapeutic targets in bipolar disorder. Expert opin ther targets. (2015) 19:747–63. doi: 10.1517/14728222.2015.1018822

71. Geoffroy PA, Scott J, Boudebesse C, Lajnef M, Henry C, Leboyer M, et al. Sleep in patients with remitted bipolar disorders: a meta-analysis of actigraphy studies. Acta psychiatr Scand. (2015) 131:89–99. doi: 10.1111/acps.12367

72. Robillard R, Naismith SL, Rogers NL, Ip TK, Hermens DF, Scott EM, et al. Delayed sleep phase in young people with unipolar or bipolar affective disorders. J affect disorders. (2013) 145:260–3. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.06.006

73. Moreira J, Geoffroy PA. Lithium and bipolar disorder: impacts from molecular to behavioural circadian rhythms. Chronobiol int. (2016) 33:351–73. doi: 10.3109/07420528.2016.1151026

74. Sit D, Wisner KL, Hanusa BH, Stull S, Terman M. Light therapy for bipolar disorder: a case series in women. Bipolar disorders. (2007) 9:918–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2007.00451.x

75. Geoffroy PA, Abbassi EMBE, Maruani J, Etain B, Lejoyeux M, Amad A, et al. Bright light therapy in the morning or at mid-day in the treatment of non-seasonal bipolar depressive episodes (LuBi): study protocol for a dose research phase I/II trial. Psychiatry Investig. (2018) 15:1188–202. doi: 10.30773/pi.2018.09.27.1

Keywords: bright light therapy, circadian rhythms, sleep, seasonal affective disorder, non-seasonal depression, bipolar disorder

Citation: Maruani J and Geoffroy PA (2019) Bright Light as a Personalized Precision Treatment of Mood Disorders. Front. Psychiatry 10:85. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00085

Received: 04 July 2018; Accepted: 06 February 2019;

Published: 01 March 2019.

Edited by:

Brisa S. Fernandes, University of Toronto, CanadaReviewed by:

Jeffrey Jay Rakofsky, Emory University, United StatesJu Wang, Tianjin Medical University, China

Copyright © 2019 Maruani and Geoffroy. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Pierre Alexis Geoffroy, pierre.a.geoffroy@gmail.com

Julia Maruani

Julia Maruani Pierre Alexis Geoffroy

Pierre Alexis Geoffroy