Classification and Outcome Measures for Psoriatic Arthritis

- 1Department of Rheumatology and Immunology, Singapore General Hospital, Duke-NUS Medical School, Singapore, Singapore

- 2Division of Rheumatology and Center for Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, United States

- 3Division of Rheumatology, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, United States

- 4Royal National Hospital for Rheumatic Diseases and Department of Pharmacy and Pharmacology, University of Bath, Bath, United Kingdom

- 5Nuffield Department of Orthopedics, Rheumatology and Musculoskeletal Sciences, University of Oxford, Oxford, United Kingdom

- 6Division of Immunology/Rheumatology, Stanford University, Palo Alto, CA, United States

- 7Department of Rheumatology Research, Swedish Medical Center, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, United States

- 8Division of Rheumatology and Krembil Research Institute, University Health Network, Toronto Western Hospital, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada

Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is an inflammatory arthritis with multiple manifestations: peripheral/axial arthritis, enthesitis, dactylitis, psoriasis, and nail involvement. From having an agreed upon classification criteria in 2006, the assessment of PsA has advanced from uncertainties to development and validation of numerous specific outcome measures. The Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic arthritis (GRAPPA) has spearheaded the development of a core domain set and is now working on a core outcome measurement set to standardize outcome measures for PsA, that will provide guidance for use of instruments in randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and longitudinal observational studies (LOS). This article summarizes and updates these work processes to improve assessment of this multisystem complex rheumatologic disease.

Introduction

Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is an inflammatory arthritis associated with psoriasis. It affects young adults of working age, with typical age of onset in the 30–50s (1). Destructive changes in bones can develop early resulting in joint damage and loss of function (2–4). Furthermore, higher inflammatory burden over time may lead to accelerated atherosclerosis, increased cardiovascular morbidity (5, 6), and possible early mortality for those with severe disease (7, 8). PsA is a unique disease entity that is different from other forms of chronic inflammatory arthritis, in terms of clinical manifestations, pathogenesis, response to treatment, and prognosis (9). Thus, clinicians and rheumatologists need to be aware of the classification and assessment of PsA to optimize care for these patients. In this article, we aim to summarize the development of classification criteria and outcome measures in PsA.

Classification Criteria

An important aspect of studying a “disease entity” is whether one can identify it as sufficiently homogenous to be distinct from other conditions. Classification criteria serve to ensure that patients recruited into RCTs have the same “disease,” so that results of these trials can be accurately interpreted (10, 11), but they are not designed for diagnostic purposes.

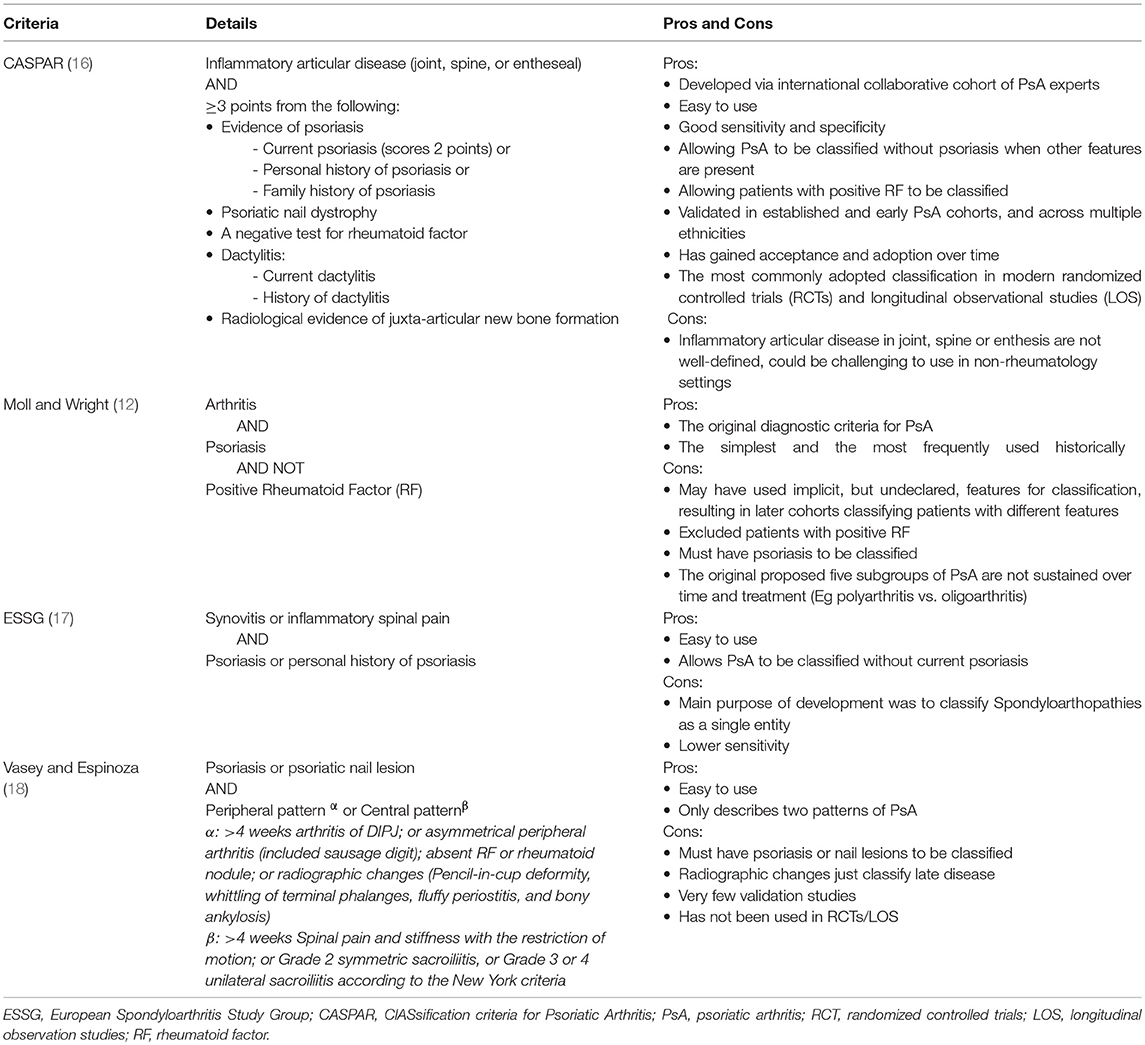

Before 2006, there were no validated case definitions or universally agreed upon classification criteria for PsA. Most historical studies used the case descriptive definition proposed by Moll and Wright (12), which defined PsA as an inflammatory arthritis in the presence of psoriasis and usually the absence of rheumatoid factor (RF). Subsequent cohorts from different centers identified different proportions of PsA patients divided into asymmetrical oligoarthritis and symmetrical polyarthritis subgroups (13, 14), possibly because of inclusion of differing proportions of RF negative rheumatoid arthritis (RA) patients based on the Moll and Wright case definition (13). Several classification criteria have subsequently been proposed (15). Table 1 summarizes the pros and cons of the various classification criteria sets for PsA. A comparative study using retrospective cross sectional and prospective multi-center datasets found high specificities (>90%), and variable sensitivities (42–98%) differentiating PsA from RA across these different classification criteria sets (15). In addition, the performance of different criteria sets distinguishing PsA from other arthritides has not been tested.

The ClASsification criteria for Psoriatic Arthritis (CASPAR) study group was established to derive new data driven classification criteria for PsA (19). The study group subsequently formed the Group for Research and Assessment in Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis (GRAPPA) including rheumatologists, dermatologists, patients and others, that, with Outcome Measures in Rheumatology (OMERACT) have pioneered the work to establish the best outcome measures for PsA. The CASPAR study group collected data prospectively from 32 centers worldwide, 588 consecutive PsA patients and the next 536 patients seen with inflammatory arthritis as the control (72% RA). PsA cases and controls were classified by existing criteria for respective accuracy, and new classification items were constructed. The CASPAR criteria (Table 1) include characteristic dermatologic, clinical, and radiographic features and have demonstrated high sensitivity (91.4%) and specificity (98.7%) (16). The CASPAR criteria enable classification of PsA in patients without psoriasis, but other associated features. The CASPAR criteria have subsequently been validated in early PsA cohorts (20, 21), retrospective cohorts (22), primary health care settings (20), and other ethnicities (23). Currently, the CASPAR criteria have become the most widely used criteria for recruitment in both RCTs and LOS (14). The only concern about the CASPAR criteria is the initial qualification criterion (stem question): inflammatory musculoskeletal (MSK) disease including either spinal, peripheral joint or entheseal manifestations. It may be difficult for practitioners other than rheumatologists, such as dermatologists, to differentiate inflammatory arthritis from other non-specific aches and pains in tendons and joints. GRAPPA is currently working on methods to better define inflammatory MSK disease (24).

More recently, the Assessment of SpondyloArthritis International Society (ASAS) developed peripheral (pSpA) and axial spondyloarthritis (AxSpA) criteria, where PsA could be classified under both pSpA or AxSpA (25). In a cohort of early arthritis, the pSpA criteria were found to have lower sensitivity for early PsA compared with the CASPAR criteria (26). However, patients with dactylitis or enthesitis or predominantly AxSpA were excluded from this validation cohort which may have limited the performance of these criteria. Moreover, all validation studies for spondyloarthritis classification criteria thus far have been based on a case control design; introducing possible bias by over-estimating sensitivity and specificity of the criteria (27). After all, constructing criteria for SpA may be challenging because it is inclusive of many heterogeneous disorders. It may be more rational to separate PsA and AxSpA into different more homogeneous phenotypic entities, thus facilitating both instrument development and measurement of clinical outcomes in the long term (28, 29).

Measurement of Meaningful Outcomes in PsA

Advances in the development of biologic therapies have offered hope for better treatment for patients with PsA since early 2000s. However, meta-analyses of results from RCTs have been hampered by the lack of homogeneity in outcome measures in PsA. Just a decade ago, most of the instruments for PsA were borrowed from RA RCTs (30, 31). Instruments that function well in other forms of arthritis may not necessarily measure what it is intended to be measured in PsA. For instance, the reduced 28-joint count in RA that focuses on hand joints grossly underestimates disease burden in PsA as the feet are most commonly affected in PsA (32). Unlike measurement of blood sugar levels in diabetes mellitus, the concept of disease control in PsA is a construct that is more difficult to define. It is generally accepted that amelioration of inflammation with effective treatment reduces symptoms, prevents damage accumulation and reduces adverse health outcomes from comorbidities. Traditional serum inflammatory biomarkers such as erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein are well-known to be elevated in < 30% of patients with active disease (33), and therefore may not reflect underlying disease activity. A challenge to quantify disease activity and impact of PsA are the diverse clinical manifestations that span across peripheral and axial joint arthritis, enthesitis, dactylitis, psoriatic skin, and nail lesions. Moreover, while disease activity and disease impact in PsA are different constructs they are not totally independent of each other. People affected by PsA may have different views compared with clinicians on which disease manifestations and impact are important to them (34).

Over the past decade, many disease specific instruments for the assessment of various domains have been developed and validated for use in RCTs (35). However, the lack of standardization of domains and instruments in RCTs is problematic. Heterogeneity in domain measurement with multiple instruments per domain in PsA RCTs (36, 37) can hinder the comparability of efficacy assessments across interventions.

Established in 1992, the OMERACT international consensus effort has been working to improve outcome measures for use in RCTs and LOS in rheumatology, building on “Truth,” “Discrimination,” and “Feasibility” (38). “Truth” means measuring what is intended to be measured in a relevant and unbiased manner. It captures issues of face, content, construct, and criterion validity. “Discrimination” means whether an instrument discriminate between situations of interest, such as disease states at different time points to measure change and also captures issues of reliability and sensitivity to change. “Feasibility” assesses whether the instrument can be easily applied, given constraints of time, money, and interpretability.

OMERACT has recently updated and outlined a conceptual framework for core set development (Filter 2.1) that encompasses both patient-centered and intervention specific information (39). This framework specifies four key components termed “Area” of a health condition to ensure comprehensive coverage: three Areas that describe the “Impact of Health Conditions,” specifically Death, Life Impact, and Resource Use; and the fourth Area that describes Pathophysiological manifestations. The OMERACT filter 2.1 has also attempted to distinguish two major components in outcome research, namely, determining “what to measure” before deciding on “how to measure” them. Within this concept, the development of “Core Domain Sets” followed by “Core Measurement Sets” with defined instruments was set forth. Each instrument in the final core measurement set must prove to be truthful, discriminative, and feasible (39).

Development of Core Domain Set for PsA

Working with OMERACT, GRAPPA researchers defined the first core domain set for use in both RCTs and LOS in 2006 (40). A need to update the core domain set was identified as our understanding of PsA advanced over the years, and to include important patient input. The concept of involving patients as research partners (PRPs) was recognized as an essential and valuable component in the process (39, 41). Without incorporating the experience of disease through involvement of patients it is not possible to fulfill the “truth” or “feasibility” element of the OMERACT filter. The role of PRPs has evolved from informing disease impact via participation in qualitative studies to much broader participation in study design and conduct (42). OMERACT has continued to publish updated guidelines on core set development. Therefore, it was deemed important to update the PsA core domain set incorporating patients' perspectives in multiple steps, and in accordance with the OMERACT filter 2.1 (43).

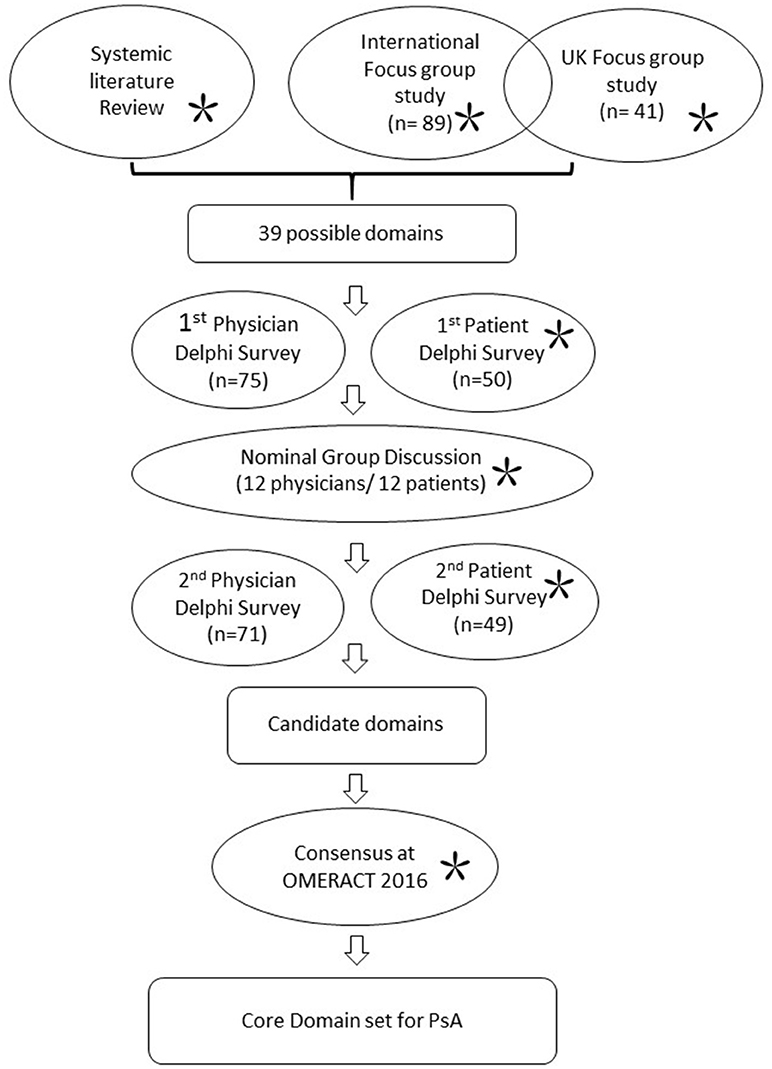

GRAPPA has assembled an international collaborative effort to update the PsA core domain set since 2014. Patients have been involved in all steps of development (conducting focus groups and analyzing data, including PRPs who functioned in the high-level conduct of the research; Figure 1). The detailed processes of core set development have been published elsewhere (44, 45). In brief, it started with identification of possible domains from a comprehensive literature search, as well as the previously identified domains from 2006 (37). Patients' perspectives on how PsA impacts their lives were actively sought through an international focus group involving 130 patients across 7 countries representing 5 continents; together with a UK multi-centered focus group study. Two independent Delphi surveys with health care providers and patients were then conducted to rate the importance of each domain. The selection of each domain was discussed in face-to-face nominal groups conducted with 12 clinicians, 12 patients, and 2 non-voting fellows in March 2016 in New Jersey, USA. Thorough exchange of ideas and perspectives between clinicians and patients were achieved, revealing differences but aiding resolution and consensus. A second Delphi survey round followed. Candidate domains were presented and endorsed at OMERACT 2016.

Figure 1. Work stream for update of core domain set for PsA 2016. Work processes in circles. *Indicates involvement of patients.

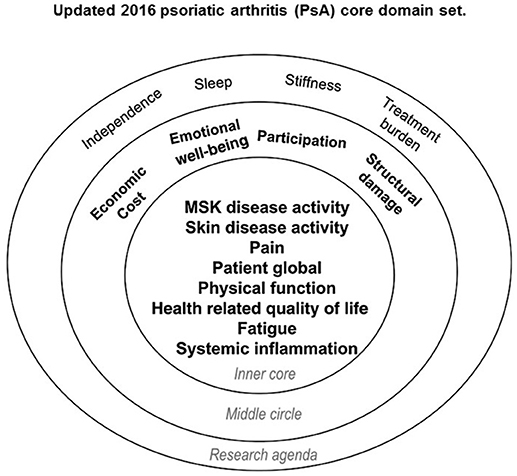

The final PsA core domain set includes three parts: an inner circle (should be measured in all RCTs and LOS), a middle circle (important to be measured at some point in the drug development program, but not mandatory), and the outer circle that represents the research agenda (Figure 2). The inner circle includes MSK disease activity (peripheral joints, enthesitis, dactylitis, and spine involvement), skin disease activity (skin and nails involvement), pain, patient's global assessment, physical function, health-related quality of life, fatigue, and systemic inflammation biomarkers (Figure 2). This core domain set, developed with extensive patient involvement and representation of stakeholders from 5 continents, achieved general consensus and provides guidance as to what to measure in PsA RCTs and LOS.

Figure 2. Updated 2016 psoriatic arthritis (PsA) core domain set. Reproduced with permission from Orbai et al. (45). Musculoskeletal (MSK) disease activity includes peripheral joints, enthesitis, dactylitis, and spine symptoms; skin activity includes skin and nails; patient global is defined as patient-reported disease-related health status. The inner circle (core) includes domains that should be measured in all randomized controlled trials and longitudinal observational studies. The middle circle includes domains that are important but may not be feasible to assess in all RCTs and LOS. The outer circle (or research agenda) includes domains that may be important but need further study.

Development of Core Outcome Measurement Set for PsA

Following development of the core domain set, the GRAPPA-OMERACT PsA core set working group is leading the work to standardize the core outcome measurement set according to the OMERACT filter methodology (46). This methodology evaluates each instrument with four pillars of OMERACT:

1) Whether an instrument is perceived as a match to the domain intended to measure by stakeholders (Domain match)

2) How feasible is the instrument to be used (Feasibility).

3) How truthful numerically it is matching to the domain or construct (Truth)

4) How responsive the instrument is to change of status of disease (Discrimination).

The work stream started with evaluation of the existing evidence on PsA instrument properties through systemic literature reviews and data analyses from RCTs, followed by Delphi processes with stakeholders (including patients, clinicians, methodologists, and payers), and working group meetings and discussion (46). Thus far, evaluation of evidence on existing patient reported outcomes (47), MSK disease activities and systemic inflammation (48) have been completed. The 66/68 joint count and Psoriatic arthritis impact of disease (PsAID12) that measure peripheral MSK disease activity and health-related quality of life or impact of disease, respectively, have been thoroughly evaluated by the GRAPPA/OMERACT working group. At the OMERACT 2018 conference in Terrigal Australia, the 66/68 joint count was endorsed and PsAID received provisional endorsement.

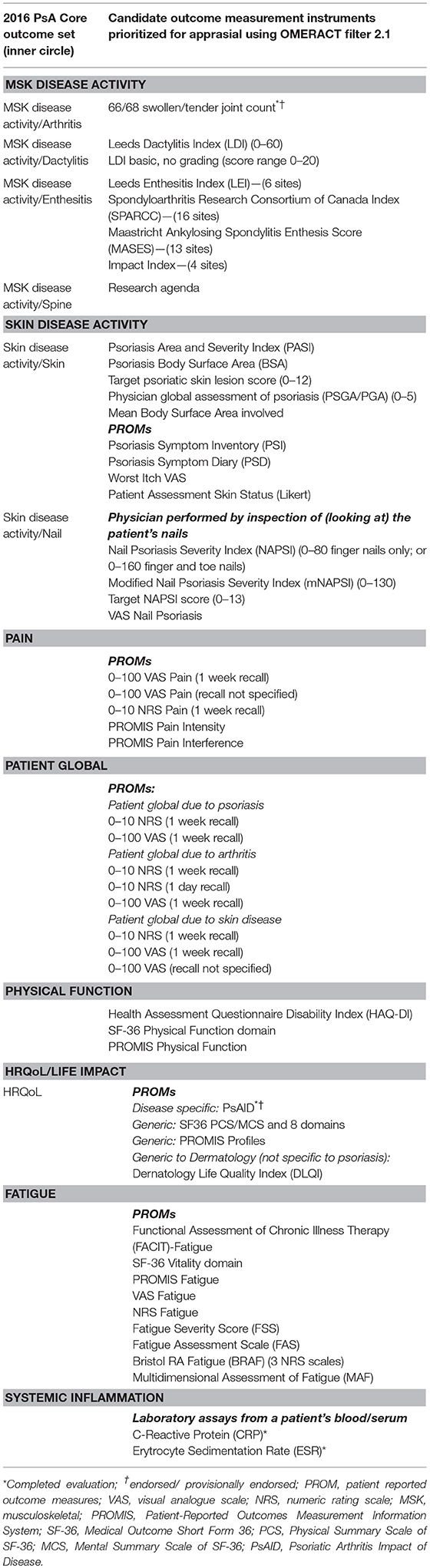

The GRAPPA core set working group will continue its work on proper evaluation of measurement properties for existing and new instruments for other domains and will seek consensus to standardize the outcome measurement set for the other domains, including MSK manifestations such as dactylitis and enthesitis; and physical function will be taken forward for appraisal using the OMERACT filter 2.1 (Table 2). The aim is to create a full core instrument set to complete the core domain set for PsA in the coming years.

Conclusion

With new therapeutic options for PsA and a growing number of RCTs and LOS in PsA, it is important to understand how best to measure disease activity and its impact. GRAPPA/OMERACT have been playing a leading role in informing how best to assess PsA. The CASPAR criteria remain the cornerstone for classifying PsA patients for enrolment in RCTs and LOS. The PsA core domain set has been updated to guide the measurement of outcomes that are relevant to both clinicians and patients. It will be important to continue to standardize outcome measures for RCTs and LOS in PsA. Using OMERACT's updated methodology to generate the best evidence will be essential establishing consensus among various stakeholders. This standardized outcome measurement set will provide a standard for subsequent RCTs/LOS in PsA, as well as to assist clinicians and patients in understanding the best evidence for a particular treatment.

Author Contributions

YYL drafted the manuscript. All authors critically reviewed the content pertaining to their expertise in the topic.

Funding

YYL is funded by the Clinician Scientist award of the National Medical Research Council, Singapore (NMRC/CSA-INV/0022/2017 and HSRG/0061/2016). The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NMRC. LC is funded by a National Institute for Health Research Clinician Scientist award. The research was supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Oxford Biomedical Research Centre (BRC). The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health. AO is funded by the Rheumatology Research Foundation and NIH/NIAMS K23 AR063764 and R01 AR072363. A-MO is funded by the Jerome L. Greene Foundation Scholar Award, the Staurulakis Family Discovery Award, the Rheumatology Research Foundation, and the National Institutes of Health (NIH) through the Rheumatic Diseases Resource-based Core Center (P30-AR053503 Cores A and D, and P30-AR070254, Cores A and B). All statements in this report, including its findings and conclusions, are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the NIH or the National Institute of Arthritis Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIAMS), or the Rheumatology Research Foundation (RRF).

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

1. Gladman DD, Chandran V. Observational cohort studies: lessons learnt from the University of Toronto psoriatic arthritis program. Rheumatology (2011) 50:25–31. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keq262

2. Gladman DD, Farewell VT. Progression in psoriatic arthritis: role of time varying clinical indicators. J Rheumatol. (1999) 26:2409–13.

3. Bond SJ, Farewell VT, Schentag CT, Gladman DD. Predictors for radiological damage in psoriatic arthritis: results from a single centre. Ann Rheum Dis. (2007) 66:370–6. doi: 10.1136/ard.2006.056457

4. Leung YY, Ho KW, Li EK, Li M, Kwok LW, Wong PC, et al. Predictors of functional deterioration in Chinese patients with psoriatic arthritis: a longitudinal study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. (2014) 15:284. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-15-284

5. Shen J, Shang Q, Li EK, Leung YY, Kun EW, Kwok LW, et al. Cumulative inflammatory burden is independently associated with increased arterial stiffness in patients with psoriatic arthritis: a prospective study. Arthritis Res Ther. (2015) 17:75. doi: 10.1186/s13075-015-0570-0

6. Horreau C, Pouplard C, Brenaut E, Barnetche T, Misery L, Cribier B, et al. Cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: a systematic literature review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. (2013) 27(Suppl. 3):12–29. doi: 10.1111/jdv.12163

7. Gladman DD, Farewell VT, Wong K, Husted J. Mortality studies in psoriatic arthritis: results from a single outpatient center. II. Prognostic indicators for death. Arthritis Rheum. (1998) 41:1103–10. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199806)41:6<1103::AID-ART18>3.0.CO;2-N

8. Ogdie A, Haynes K, Troxel AB, Love TJ, Hennessy S, Choi H, et al. Risk of mortality in patients with psoriatic arthritis, rheumatoid arthritis and psoriasis: a longitudinal cohort study. Ann Rheum Dis. (2014) 73:149–53. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-202424

9. Coates LC, Fransen J, Helliwell PS. Defining minimal disease activity in psoriatic arthritis: a proposed objective target for treatment. Ann Rheum Dis. (2010) 69:48–53. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.102053

10. Singh JA, Solomon DH, Dougados M, Felson D, Hawker G, Katz P, et al. Development of classification and response criteria for rheumatic diseases. Arthritis Rheum. (2006) 55:348–52. doi: 10.1002/art.22003

11. Aggarwal R, Ringold S, Khanna D, Neogi T, Johnson SR, Miller A, et al. Distinctions between diagnostic and classification criteria? Arthritis Care Res. (2015) 67:891–7. doi: 10.1002/acr.22583

12. Moll JM, Wright V. Psoriatic arthritis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. (1973) 3:55–78. doi: 10.1016/0049-0172(73)90035-8

13. Helliwell PS, Taylor WJ. Classification and diagnostic criteria for psoriatic arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. (2005) 64(Suppl. 2):ii3–8. doi: 10.1136/ard.2004.032318

14. Ogdie A, Weiss P. The epidemiology of psoriatic arthritis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. (2015) 41:545–68. doi: 10.1016/j.rdc.2015.07.001

15. Taylor WJ, Marchesoni A, Arreghini M, Sokoll K, Helliwell PS. A comparison of the performance characteristics of classification criteria for the diagnosis of psoriatic arthritis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. (2004) 34:575–84. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2004.05.001

16. Taylor W, Gladman D, Helliwell P, Marchesoni A, Mease P, Mielants H, et al. Classification criteria for psoriatic arthritis: development of new criteria from a large international study. Arthritis Rheum. (2006) 54:2665–73. doi: 10.1002/art.21972

17. Dougados M, van der Linden S, Juhlin R, Huitfeldt B, Amor B, Calin A, et al. The european spondylarthropathy study group preliminary criteria for the classification of spondylarthropathy. Arthritis Rheum. (1991) 34:1218–27. doi: 10.1002/art.1780341003

18. Vasey F, Espinoza LR. Psoriatic arthropathy. In: Calin A, editor. Spondyloarthropathies. Orlando, FL: Grune and Stratton (1984). p. 151–85.

19. Taylor WJ, Helliwell PS. Development of diagnostic criteria for psoriatic arthritis: methods and process. Curr Rheumatol Rep. (2004) 6:299–305. doi: 10.1007/s11926-004-0042-z

20. Chandran V, Schentag CT, Gladman DD. Sensitivity and specificity of the CASPAR criteria for psoriatic arthritis in a family medicine clinic setting. J Rheumatol. (2008) 35:2069–70. Available online at: http://www.jrheum.org/content/35/10/2069

21. Coates LC, Conaghan PG, Emery P, Green MJ, Ibrahim G, MacIver H, et al. Sensitivity and specificity of the classification of psoriatic arthritis criteria in early psoriatic arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. (2012) 64:3150–5. doi: 10.1002/art.34536

22. Tillett W, Costa L, Jadon D, Wallis D, Cavill C, McHugh J, et al. The classification for psoriatic arthritis (CASPAR) criteria–a retrospective feasibility, sensitivity, and specificity study. J Rheumatol. (2012) 39:154–6. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.110845

23. Leung YY, Tam LS, Ho KW, Lau WM, Li TK, Zhu TY, et al. Evaluation of the CASPAR criteria for psoriatic arthritis in the Chinese population. Rheumatology (Oxford) (2010) 49:112–5. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kep348

24. Mease PJ, Garg A, Helliwell PS, Park JJ, Gladman DD. Development of criteria to distinguish inflammatory from noninflammatory arthritis, enthesitis, dactylitis, and spondylitis: a report from the GRAPPA 2013 annual meeting. J Rheumatol. (2014) 41:1249–51. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.140182

25. Rudwaleit M, van der Heijde D, Landewe R, Akkoc N, Brandt J, Chou CT, et al. The assessment of spondyloarthritis international society classification criteria for peripheral spondyloarthritis and for spondyloarthritis in general. Ann Rheum Dis. (2011) 70:25–31. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.133645

26. van den Berg R, van Gaalen F, van der Helm-van, Mil A, Huizinga T, van der Heijde D. Performance of classification criteria for peripheral spondyloarthritis and psoriatic arthritis in the leiden early arthritis cohort. Ann Rheum Dis. (2012) 71:1366–9. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-201081

27. Whiting PF, Rutjes AW, Westwood ME, Mallett S, Deeks JJ, Reitsma JB, et al. QUADAS-2: a revised tool for the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies. Ann Intern Med. (2011) 155:529–36. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-155-8-201110180-00009

28. Nash P, Mease PJ, Braun J, van der Heijde D. Seronegative spondyloarthropathies: to lump or split? Ann Rheum Dis. (2005) 64(Suppl. 2):ii9–13. doi: 10.1136/ard.2004.033654

29. Taylor WJ, Robinson PC. Classification criteria: peripheral spondyloarthropathy and psoriatic arthritis. Curr Rheumatol Rep. (2013) 15:317. doi: 10.1007/s11926-013-0317-3

30. Mease PJ, Antoni CE, Gladman DD, Taylor WJ. Psoriatic arthritis assessment tools in clinical trials. Ann Rheum Dis. (2005) 64(Suppl. 2):ii49–54. doi: 10.1136/ard.2004.034165

31. Wong PC, Leung YY, Li EK, Tam LS. Measuring disease activity in psoriatic arthritis. Int J Rheumatol. (2012) 2012:839425. doi: 10.1155/2012/839425

32. Coates LC, FitzGerald O, Gladman DD, McHugh N, Mease P, Strand V, et al. Reduced joint counts misclassify patients with oligoarticular psoriatic arthritis and miss significant numbers of patients with active disease. Arthritis Rheum. (2013) 65:1504–9. doi: 10.1002/art.37939

33. Gladman DD, Mease PJ, Choy EH, Ritchlin CT, Perdok RJ, Sasso EH. Risk factors for radiographic progression in psoriatic arthritis: subanalysis of the randomized controlled trial ADEPT. Arthritis Res Ther. (2010) 12:R113. doi: 10.1186/ar3049

34. Eder L, Thavaneswaran A, Chandran V, Cook R, Gladman DD. Factors explaining the discrepancy between physician and patient global assessment of joint and skin disease activity in psoriatic arthritis patients. Arthritis Care Res. (2015) 67:264–72. doi: 10.1002/acr.22401

35. Mease PJ. Measures of psoriatic arthritis: tender and Swollen Joint Assessment, Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI), Nail Psoriasis Severity Index (NAPSI), Modified Nail Psoriasis Severity Index (mNAPSI), Mander/Newcastle Enthesitis Index (MEI), Leeds Enthesitis Index (LEI), Spondyloarthritis Research Consortium of Canada (SPARCC), Maastricht Ankylosing Spondylitis Enthesis Score (MASES), Leeds Dactylitis Index (LDI), Patient Global for Psoriatic Arthritis, Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI), Psoriatic Arthritis Quality of Life (PsAQOL), Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Fatigue (FACIT-F), Psoriatic Arthritis Response Criteria (PsARC), Psoriatic Arthritis Joint Activity Index (PsAJAI), Disease Activity in Psoriatic Arthritis (DAPSA), and Composite Psoriatic Disease Activity Index (CPDAI). Arthritis Care Res. (2011) 63(Suppl. 11):S64–85. doi: 10.1002/acr.20577

36. Ramiro S, Smolen JS, Landewe R, Heijde DV, Gossec L. How are enthesitis, dactylitis and nail involvement measured and reported in recent clinical trials of psoriatic arthritis? A systematic literature review. Ann Rheum Dis. (2018) 77:782–3. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2017-211447

37. Kalyoncu U, Ogdie A, Campbell W, Bingham CO III, de Wit M, Gladman DD, et al. Systematic literature review of domains assessed in psoriatic arthritis to inform the update of the psoriatic arthritis core domain set. RMD Open (2016) 2:e000217. doi: 10.1136/rmdopen-2015-000217

38. Boers M, Brooks P, Strand CV, Tugwell P. The OMERACT filter for outcome measures in rheumatology. J Rheumatol. (1998) 25:198–9.

39. Boers M, Kirwan JR, Wells G, Beaton D, Gossec L, d'Agostino MA, et al. Developing core outcome measurement sets for clinical trials: OMERACT filter 2.0. J Clin Epidemiol. (2014) 67:745–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.11.013

40. Gladman DD, Mease PJ, Strand V, Healy P, Helliwell PS, Fitzgerald O, et al. Consensus on a core set of domains for psoriatic arthritis. J Rheumatol. (2007) 34:1167–70. Available online at: http://www.jrheum.org/content/34/5/1167

41. de Wit MP, Berlo SE, Aanerud GJ, Aletaha D, Bijlsma JW, Croucher L, et al. European league against rheumatism recommendations for the inclusion of patient representatives in scientific projects. Ann Rheum Dis. (2011) 70:722–6. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.135129

42. de Wit M, Abma T, Koelewijn-van Loon M, Collins S, Kirwan J. Involving patient research partners has a significant impact on outcomes research: a responsive evaluation of the international OMERACT conferences. BMJ Open (2013) 3:e002241. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-002241

43. Tillett W, Eder L, Goel N, De Wit M, Gladman DD, FitzGerald O, et al. Enhanced patient involvement and the need to revise the core set - report from the psoriatic arthritis working group at OMERACT 2014. J Rheumatol. (2015) 42:2198–203. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.141156

44. Orbai AM, de Wit M, Mease PJ, Callis Duffin K, Elmamoun M, Tillett W, et al. Updating the psoriatic arthritis (PsA) core domain set: a report from the PsA workshop at OMERACT 2016. J Rheumatol. (2017) 44:1522–8. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.160904

45. Orbai AM, de Wit M, Mease P, Shea JA, Gossec L, Leung YY et al. International patient and physician consensus on a psoriatic arthritis core outcome set for clinical trials. Ann Rheum Dis. (2017) 76:673–80. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-210242

46. Ogdie A, de Wit M, Callis Duffin K, Campbell W, Chau J, Coates LC, et al. Defining outcome measures for psoriatic arthritis: a report from the GRAPPA-OMERACT working group. J Rheumatol. (2017) 44:697–700. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.170150

47. Hojgaard P, Klokker L, Orbai AM, Holmsted K, Bartels EM, Leung YY, et al. A systematic review of measurement properties of patient reported outcome measures in psoriatic arthritis: a GRAPPA-OMERACT initiative. Semin Arthritis Rheum. (2018) 47:654–65. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2017.09.002

48. Elmamoun M, Leung YY, O'Sullivan D, Steinkoenig I, Chandran V, Gladman DD, et al. Systematic literature review of systemic inflammation, using Creactive protein and erythrocyte sedimentation rate, in psoriatic arthritis to inform the development of instruments for the updated psoriatic arthritis core outcome measurement Set. J Rheumatol. (in press).

Keywords: psoriatic arthritis, outcome measures, core domains, core instruments, classification criteria

Citation: Leung YY, Ogdie A, Orbai A-M, Tillett W, Coates LC, Strand V, Mease P and Gladman DD (2018) Classification and Outcome Measures for Psoriatic Arthritis. Front. Med. 5:246. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2018.00246

Received: 12 June 2018; Accepted: 15 August 2018;

Published: 06 September 2018.

Edited by:

Vasco C. Romão, Instituto de Medicina Molecular (IMM), PortugalReviewed by:

Alexandre Sepriano, Leiden University Medical Center, NetherlandsAnabela Barcelos, Centro Hospitalar Baixo Vouga, Portugal

Copyright © 2018 Leung, Ogdie, Orbai, Tillett, Coates, Strand, Mease and Gladman. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ying Ying Leung, katyccc@hotmail.com

Ying Ying Leung

Ying Ying Leung Alexis Ogdie2

Alexis Ogdie2