Does the Use of Complex Sentences Differentiate Between Bilinguals With and Without DLD? Evidence From Conversation and Narrative Tasks

- 1Department of Linguistics, University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB, Canada

- 2School of Linguistics and Language Studies, Carleton University, Ottawa, ON, Canada

Over-identification of language disorder among bilingual children with typical development (TD) is a risk factor in assessment. One strategy for improving assessment accuracy with bilingual children is to determine which linguistic sub-domains differentiate bilingual children with TD from bilingual children with developmental language disorder (DLD). To date, little research on sequential bilinguals with TD and DLD has focussed on complex (multi-clausal) sentences in naturalistic production, even though this is a noted domain of weakness for school-age monolinguals with DLD. Accordingly, we sought to determine if there were differences in the use of complex sentences in conversational and narrative tasks between school-age sequential bilinguals with TD and with DLD at the early stages of L2 acquisition. We administered a conversation and a narrative task to 63 English L2 children with TD and DLD, aged 5–7 years with 2 years of exposure to the L2. Children had diverse first language backgrounds. The L2-TD and L2-DLD groups were matched for age, length of L2 exposure and general L2 proficiency (receptive vocabulary size). Language samples from both tasks were coded and analyzed for the use of complex versus simple sentences, for the distribution of complex sentence types, for clausal density and mean length of utterance (MLU). Complex sentences included coordinated clauses, sentential complement clauses, adverbial clauses and relative clauses. Using regression modelling and PERMANOVA, we found that the L2-TD group produced more complex sentences than the L2-DLD group, with coordinated clauses, adverbial clauses and relative clauses differing the most between the groups. Furthermore, the two groups differed for mean clausal density, but not for MLU, indicating that clausal density and MLU did not estimate identical morphosyntactic abilities. Individual variation in complex sentence production for L2-TD was predicted by longer L2 exposure and task; by contrast, for L2-DLD, it was predicted by older age. This study indicates that complex sentence production is an area of weakness for bilingual children with DLD, as it is for monolinguals with DLD. The clinical implications of these findings are discussed.

Introduction

Sequential bilingual children who speak a heritage first language (L1) and are in the process of acquiring the majority second language (L2) in the early school years are at risk for over-identification of language disorders (Kay-Raining Bird et al., 2016; Paradis et al., 2021). A key reason for this risk is that the incompletely learned L2 of bilingual children in the early school years has characteristics that overlap with those of monolingual children with language disorders the same age (Paradis, 2005; Paradis, 2016; Scheidnes and Tuller, 2019). This overlap complicates assessment based on tests and protocols designed for, and normed with, monolinguals. The risk of over-identification is particularly high for developmental language disorder (DLD; also referred to as specific language impairment or SLI) because this is a disorder where language learning and representation are the locus of impairment, and children with DLD have no other clinically significant conditions, for example, no autistic symptoms, no intellectual disabilities, no hearing loss (Leonard, 2014). One line of research aimed at addressing the issue of over-identification is focused on determining which linguistic sub-domains best differentiate bilingual children with typical development (TD) from bilingual children with DLD. To date, little research on sequential bilinguals with TD and DLD has focussed on the use of complex (multi-clausal) sentences in naturalistic production (conversation or narrative tasks), even though this is a noted domain of weakness for school-age monolinguals with DLD, in English and in other languages (Leonard, 2014; Fletcher and Frizelle, 2017).

Investigating the use of complex (multi-clausal) sentences in production by bilinguals with and without DLD is motivated for several reasons. First, TD bilinguals produce complex sentences frequently and accurately early on in their English L2 acquisition (Paradis et al., 2017), in contrast to their acquisition of L2 morphology (Chondrogianni and Marinis, 2011; Paradis, 2011). If use of complex sentences in the L2 is a domain of relative strength for TD bilinguals, it might have the potential to discriminate them from bilinguals with DLD. Second, there is little overlap between TD bilinguals and monolinguals with DLD in their abilities with complex syntax (Scheidnes and Tuller, 2019), in contrast with morphology (Paradis, 2005; Paradis, 2016), which also suggests that complex syntax has the potential to differentiate between bilinguals with TD and those with DLD. Third, sentence repetition tasks that include complex sentences show promise for clinical assessment with bilinguals (Armon-Lotem and Meir, 2016; Meir et al., 2016); however, existing tasks include a small number of tokens for diverse complex syntactic structures, which makes it difficult to ascertain the differentiation potential of multi-clausal sentences specifically. Evidence of differentiation potential from more naturalistic, hence ecologically valid, language production tasks could provide additional support for the inclusion of multi-clausal sentences on sentence repetition tasks used with bilinguals. Finally, uncovering whether complex sentences is a relative weakness for bilinguals with DLD in their naturalistic L2 production could have clinical relevance for both assessment and intervention planning (cf. Marinellie, 2004).

Accordingly, in this study, we compared the naturalistic production of complex sentences in school-age sequential bilinguals with TD and with DLD who are English L2 learners with diverse L1 backgrounds. Our overall objective was to determine whether there were differences between the two groups in the use of complex sentences in the L2. Specific objectives included the following: 1) assessing the differentiation potential of individual types of complex sentences as well as mean clausal density versus mean length of utterance (MLU); 2) examining the role of task (conversation or narration), and individual difference factors (age and length of L2 exposure), on children’s performance.

Complex Sentences in English

Complex sentences are sentences that are multi-clausal, as opposed simple, single clause sentences. In complex sentences, clauses are either joined through coordination or embedding/subordination. The different types of complex sentences that were examined in the present study are illustrated in (1). For more information on these complex sentence types, see Paradis et al. (2017) and Frizelle et al. (2018). The system used for coding complex sentences in the language samples for the present study is provided in Section 2.

1) Complex sentence types

a) (The rabbit hugged the bear) and (the bear wagged her tail). Coordinated Clauses

b) (The rabbit hugged the bear) and (smiled brightly). Coordinated Clauses, matrix subject elided in second clause

c) The bear wanted (to eat some honey). Sentential Complement, nonfinite

d) The bear said (that she wanted to eat honey). Sentential Complement, finite

e) The rabbit hopped away (after hugging the bear). Adverbial Clause, nonfinite

f) The rabbit hopped away (after she hugged the bear). Adverbial Clause, finite

g) The bear saw (the rabbit who hugged her) in the forest. Relative Clause, object

h) The bear (who the rabbit hugged) ate the honey. Relative Clause, subject

Complex Sentences in Production: Monolinguals With TD and With DLD

Children learning English as their L1 do not use complex sentences frequently in their naturalistic production during the preschool years. For example, Diessel (2004) and Vasilyeva et al. (2008) found that complex sentences comprised less than 10% of all sentences from ages 2; 0–4; 0, with use of complex sentences increasing from a minimum of 1% at emergence to an average of 10–14% of all sentences by age 4; 0. In addition, Diessel suggested that some early emerging complex sentences were not fully productive but instead were likely based on memorized, unanalyzed constructions. This suggestion is based on the finding that the same verb frame for a complex sentence type appeared multiple times, e.g., I want to + verb. Regarding sequence of emergence, both Diessel (2004) and Vasilyeva et al. (2008) found that sentential complement clauses were used first, followed by coordinated clauses, adverbial clauses, and then relative clauses. Importantly, this order of emergence also corresponds to the relative frequency of complex sentence types in children’s speech, that is, at all ages in the preschool years, the frequency of sentential complements is higher than relative clauses (Vasilyeva et al., 2008). This relative frequency also corresponds to the distribution in caregiver speech in the preschool years (Diessel, 2004).

Frizelle et al. (2018) conducted a large-scale study on the production of complex sentences in language samples from school age English L1 children from 4 years to adolescence. They found that simple or single clause sentences were the most common type across all ages, with use of multi-clausal sentences, as measured by clausal density, growing after the ages of 4–5 years, with growth stabilizing after age seven until about 10 years of age. All complex sentence types were present in the children’s samples, at least one token for each participant, starting from age four. Regarding the distribution of complex sentence types, the most frequent was coordinated clauses, followed by sentences with embedded clauses, e.g., sentential complement clauses, adverbial clauses and relative clauses. Among embedded clauses, adverbials were the most frequent among the elementary school age children. Thus, the distribution of complex sentence types seems to shift from the preschool to the school age years, with sentential complements being the most frequent for preschoolers, while coordinated clauses were the most frequent for school age children.

Production of complex sentences also grows for English L1 children with DLD from preschool to late elementary school, but they use complex sentences less frequently and make more structural errors with them than their TD peers (Fletcher and Frizelle, 2017). Studies with five- and eight-year-olds found differences in the production of sentential complement clauses between children with DLD and TD on elicitation tasks (Eisenberg, 2004; Owen and Leonard, 2006). Hesketh (2004) found that children with DLD showed increases in their use of complex sentence types from the ages of 6–11 years, as measured by elicitation and narrative tasks. However, differences between English L1 children with TD and DLD persist even toward the end of elementary school. Marinellie (2004) found that 10-year-old children with DLD produced complex sentences (coordinated clauses, adverbial clauses, relative clauses and sentential complements) in a conversation task less often than same age TD peers. A longitudinal case study of a child with DLD showed a similar distribution of complex sentence types as TD children, but with a delay in emergence and lower frequency of use (Schuele and Dykes, 2005). Studies using sentence repetition tasks or expository language samples have shown relative clauses to be good discriminators of children with DLD among English monolinguals from early elementary school to adolescence (Nippold et al., 2008; Riches et al., 2010; Frizelle and Fletcher, 2014), also indicating that production of complex sentences is a persistent area of difficulty for children with DLD. Fletcher and Frizelle (2017) suggest that difficulties with complex syntax could be a proximal cause of the depressed academic outcomes often documented for children with DLD. The association between facility with complex syntax and reading comprehension in TD children is consistent with this suggestion (Scott, 2009; MacKay et al., 2021).

Complex Sentences in Production: Bilinguals With TD and With DLD

In comparison to monolingual English-speaking children, there is less research on complex sentences in production among bilingual children, with or without DLD. Paradis et al. (2017) conducted a study on complex sentences with 187 five- and six-year-old sequential bilinguals with English as their L2 and diverse L1 backgrounds. Conversation and narrative samples were analyzed for the use of simple and complex sentences, and for different complex sentence types (sentential complement clauses, coordinated clauses, adverbial clauses and relative clauses). Results showed similarities and differences with the developmental patterns of younger, English L1 speakers. Similarities included the relative distribution of different complex sentence types and a general increase in the use of complex sentences along with increased exposure to English (analogous to increase in age among monolinguals). A difference was found in the proportion of complex sentences used. These school-age L2 children, with an average of 17 months of L2 exposure in school, used more complex sentences in their language production than monolingual four-year-olds, as reported in Diessel (2004) and Vasilyeva et al. (2008): 18% of all complete sentences were complex in the language samples of these L2 children (Paradis et al., 2017, p. 9). In Frizelle et al. (2018), English L1 children in the age bands from 5 to 7 years produced complex sentences as approximately 22–30% of all utterances, which is more than the L2 children in Paradis et al. (2017). But, considering the gap in length of exposure to English between these bilinguals and monolinguals (less than 2 years vs. 5–7 years), the sequential bilinguals are not lagging far behind. Taken together, these comparisons suggest that the acquisition of complex syntax is a relative strength at the early stages of child L2 acquisition. It is possible that older age, i.e., cognitive and linguistic maturity, at the onset of L2 acquisition, as well as exposure to academic language in school, contributes to their precocious development.

Cahill et al. (2020) also examined morphosyntax in language samples from bilingual school age children (7–11 years old) on expository and narrative tasks in English. While their participants were simultaneous French-English bilinguals (children who were exposed to both languages from birth), rather than sequential English L2 children from diverse L1 backgrounds, their results are relevant to the present study. They examined MLU, clausal density and wh-object constructions in the language samples and found limited differences between bilinguals and monolinguals; the most prominent differences they found were based on age not language background. Therefore, as with Paradis et al. (2017), this study suggests that syntactic abilities could be a relative strength in bilingual speakers of English. Findings from Scheidnes and Tuller (2019) also support the notion of complex syntax as a relative strength for L2 speakers with typical development. These researchers examined clausal embedding as well as morphosyntactic errors in conversational language samples from English L1-French L2 children and monolingual French L1 children with DLD, in France. They found that there was greater overlap between the bilinguals with TD and the monolinguals with DLD for morphosyntactic errors than for clausal embedding. These researchers note that ideal linguistic targets for discrimination are those that emerge early in TD L2 acquisition, like clausal embedding/complex sentences.

Studies examining complex sentences in bilinguals with DLD using naturalistic production tasks have been limited to date. Some studies of narrative macrostructure and microstructure in bilinguals with DLD have included analyses of syntactic complexity (Squires et al., 2014; Tsimpli et al., 2016). Squires et al. (2014) looked at the appearance of coordinating and subordinating conjunctions (indexing the use of multi-clause sentences) in the narratives of Spanish-English bilinguals with TD and with DLD in kindergarten and in first grade. They found that the TD group produced more of these conjunctions than the DLD group at both time periods. In a study of nine-year-old bilinguals with years of exposure to Greek as an L2, Tsimpli et al. (2016) found that bilinguals with TD outperformed bilinguals with DLD on the use of subordinate clauses. Meir et al. (2016) conducted a study using a sentence repetition task with Russian L1-Hebrew L2 children with TD and DLD. The children with DLD showed unique error patterns with respect to complex sentences such as, omission of subordinate and coordinate conjunctions as well as simplification of relative clauses. This study points to extra difficulties with complex sentences on the part of bilingual children with DLD, consistent with naturalistic production studies.

In sum, existing research on the naturalistic production of complex sentences in bilinguals with TD and with DLD is limited compared to the research with monolinguals. Nevertheless, the relative strength of complex syntax use in the early stages of L2 acquisition and the findings to date on bilinguals with DLD motivate further research into the differentiation potential of complex sentence use in L2 production.

Clausal Density Versus Mean Length of Utterance

Use of complex sentences in conversation or narrative production can be measured using clausal density: how many clauses per sentence on average (Frizelle et al., 2018) or by comparing the proportion of simple vs. complex sentences used (Paradis et al., 2017). In either case, this measure of growth in complex syntax is focused on use of multi-clause sentences specifically. As such, there is a difference between mean clausal density and MLU as a measure of syntactic growth. MLU consists of the average number of words or morphemes per utterance in a language sample; therefore, MLU is a more general measure in that it captures the addition of adjective or adverb phrases and grammatical morphology to lengthen utterances/sentences, rather than measuring the use of multiple clauses in particular (cf. Frizelle et al., 2018; Cahill et al., 2020).

In monolinguals, MLU is a long-standing measure of overall morphosyntactic ability and it correlates with age in the preschool years until about age four (Brown, 1973; Miller and Chapman, 1981). After age four, MLU is not widely used in research with monolinguals, but there is evidence that MLU does increase with age throughout the elementary school years, and that it is correlated with clausal density, which also increases (Frizelle et al., 2018). Nippold et al. (2008) found that mean length of turn (a general measure of morphosyntax like MLU) differentiated between English adolescents with TD and DLD. Nevertheless, Frizelle et al. (2018) found that clausal density accounted for variance that MLU did not, indicating that they do not measure identical morphosyntactic abilities. Turning to bilinguals, Paradis and Kirova (2014) found that 4.5-year-old English L2 children with diverse L1 backgrounds performed closer to monolingual age-based expectations for a measure of clausal density than for MLU on a narrative task. Thus, Paradis and Kirova (2014)’s results also suggest that MLU and clausal density measure different morphosyntactic abilities. By contrast, Cahill et al. (2020) compared MLU with clausal density in French-English bilinguals and monolinguals and found them to have similar sensitivity to age. To date, the extent to which MLU and clausal density differ between bilingual children with TD and DLD has not been examined. Accordingly, we do so in this study.

Language Sample Task Demands

Research with TD monolingual children has revealed that they use morphosyntax differentially according to how cognitively demanding a language production task is. Conversation tasks are considered less demanding than narrative tasks and expository discourse tasks are possibly the most demanding. Westerveld and Vidler (2016) compared five- to eight-year-old children’s MLU from four different language production tasks (conversation, personal narrative, fictional narrative retell, and expository) and found that children’s MLU was lower for conversation than for the other tasks. Both MLU and syntactic complexity have been found to be higher on narrative than conversation tasks in TD adolescents; moreover, monolinguals with DLD were better differentiated from their TD peers on an expository than a conversation task (Nippold et al., 2008; Nippold et al., 2014). Similar research with TD bilinguals is more limited and findings are mixed. Cahill et al. (2020) found that clausal density and MLU were relatively equal with respect to growth according to age for simultaneous bilinguals, but both were higher on an expository than a narrative task, in line with expectations based on task demands. By contrast, Paradis et al. (2017) found that sequential bilinguals used more complex sentences in a conversation than a narrative task; in other words, in the reverse of expectations based on task demands. This difference could be due to the bilinguals in Cahill et al. (2020) being older and having longer exposure to English than the bilinguals in Paradis et al. (2017); in other words, the expected task effects might emerge more clearly as cognitive maturity and linguistic proficiency in the language of testing increases. Currently, it is unknown how task demands might affect production of complex sentences in bilinguals with DLD; therefore, we examine this in the present study.

Sources of Individual Differences in Bilinguals With TD and DLD

There is a growing body of research showing that factors such as L1 typology, age, input quality and quantity and family socio-economic status predict variation in bilingual children’s acquisition of their L1 and their L2 (for reviews, Unsworth, 2016; Armon-Lotem et al., 2019; Paradis et al., 2021). In comparison to the studies with bilingual children with TD, there have been fewer studies exploring sources of individual differences in bilinguals with DLD (Blom and Paradis, 2015; Altman et al., 2016; Govindarajan and Paradis, 2019). In Blom and Paradis (2015), an English inflectional morphology task was administered to school-age sequential bilinguals with TD and with DLD. Older age at testing predicted better performance on the task for both participant groups. In contrast, longer exposure to L2 English in school predicted better performance for the TD bilinguals but not for bilinguals with DLD. TD bilinguals’ performance on the task also showed they were better able to transfer knowledge from their L1 to their L2 than the bilinguals with DLD. Similarly, Altman et al. (2016) noted that longer exposure to the L2 (Hebrew) was associated with higher MLUs for English-Hebrew bilingual preschoolers with TD, but not with DLD. Govindarajan and Paradis (2019) found that age and input factors differentially affected the narrative task performance of sequential bilinguals with TD and DLD, aged 5–7 years old. They found that older age at testing predicted higher MLUs for bilinguals with DLD; whereas, longer exposure to English and more richness in the English environment at home (quality and quantity of L2 input) predicted higher MLUs and better narrative macrostructure for the bilinguals with TD. Taken together, these studies point to L2 input factors having less impact on bilinguals with DLD than with TD. Blom and Paradis (2015) suggested that bilingual children with DLD might be less able to make effective use of their L2 input because of the verbal memory and processing limitations that most children with DLD have (e.g., Leonard, 2014). Following this line of research, we examine the influence of individual differences in age and length of L2 exposure on the children’s production of complex sentences.

The Present Study

English L2 children from diverse L1 backgrounds, with TD (L2-TD) and with DLD (L2-DLD), participated this study. Children were 5–7 years of age and were attending English medium schools in English majority language cities in Canada. L2-TD and L2-DLD were matched groupwise for length of L2 exposure, age at testing and general English L2 proficiency, as indexed by receptive vocabulary. Children produced a conversation and a narrative language sample, and these were examined for the use of simple and complex sentences, complex sentence types, clausal density and MLU. Parent interviews yielded information on individual difference factors, age at testing and length of L2 exposure. Our primary objective was to determine whether sequential bilinguals with TD could be distinguished from bilinguals with DLD by their use of complex sentences in naturalistic production at the early stages of L2 acquisition. The following research questions guided our analyses:

1) Does group membership (L2-DLD or L2-TD) predict the frequency of sentence types produced while controlling for length of L2 exposure? Sentence types include simple vs. complex as well as the different types of complex sentences.

2) Does group membership (L2-DLD or L2-TD) predict overall clausal density and MLU while controlling for length of L2 exposure? Does the same pattern hold for clausal density and MLU?

3) Is there a difference between production of complex sentences in conversational versus narrative language samples? Is this the same for both groups?

4) How does individual variation in age and length of L2 exposure predict the use of complex sentences? Does the relative influence of these factors differ between groups?

Methods and Materials

Participants

Participants were 63 sequential bilinguals with diverse L1 backgrounds who were acquiring English as their L2 in Canada (L1s = Arabic, Assyrian, Cantonese, Chinese, Gujarati, Hindi, Mandarin, Punjabi, Somali, Spanish, Urdu and Vietnamese). Children had foreign-born parents who were L2 speakers of English. Thirty-five percent of the children were also foreign-born. According to parent report, the Canadian-born children were not consistently exposed to English until they started a preschool or school program. To verify that the Canadian-born children had not received substantial exposure to English, such that they may have had more advanced language abilities, we compared the receptive vocabulary and clausal density scores (detailed below) of children who were Canadian-born and foreign-born. There was no significant difference in scores across these groups of children and the effect sizes were negligible (for receptive vocabulary: W = 426, p = 0.56, d = −0.05; for clausal density: W = 424, p = 0.54, d = 0.006). Accordingly, we combined the Canadian-born and foreign-born children into a single group of child L2 learners. Children’s overall length of exposure to English (the L2) averaged 23 months (SD = 9.65 months). Children were, on average, aged 5; 7 (SD = 5.35 months) at the time of data collection.

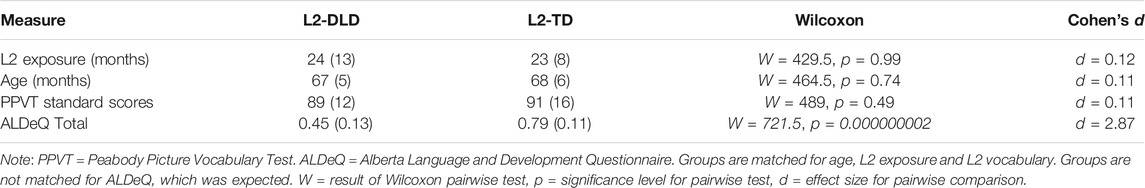

The children in this sample were divided into two groups: 1) those who had typical language development (L2-TD, n = 42) and 2) those who were identified as having developmental language disorder (L2-DLD, n = 21). The children in the L2-TD group were recruited through schools as well as through agencies who support newcomer families. They were all attending regular kindergarten (first year of school) or Grade 1 classes, with no history of special education placements or diagnoses of developmental difficulties or delays, according to parental report. The children in the L2-TD group were selected from a larger sample of children to groupwise match with the children in the L2-DLD group on the basis of L2 exposure and age (Table 1). Groupwise matching consisted of Wilcoxon signed-rank tests as well as effect size calculations (Kover and Atwood, 2013). Results in Table 1 show non-significant pairwise tests as well as effect size differences of 0.20 or lower (small). Both of these results indicate groupwise equivalencies for age and L2 exposure. Equivalencies for L2 receptive vocabulary abilities were artifactual, see Vocabulary Task in Section 2.2 below.

TABLE 1. Groupwise matching of TD and DLD groups based on age, exposure, L2 vocabulary and ALDeQ score.

The children in the L2-DLD group were referred to our research team by registered speech-language pathologists who were working with these children, either by providing individual support or through school-based group programs. Since children were referred from several programs, the speech-language pathologists did not rely on a single assessment measure, but instead, assessments were based on a variety of standardized assessment instruments. Notably, all assessment techniques had been approved by the health district for use in the identification of DLD. The inclusion and exclusion criteria were clearly detailed to all speech-language pathologists who referred children to this study. To be included in the L2-DLD group, children needed to exhibit language impairment and to be L2 learners of English. Children were excluded from the L2-DLD group if they had hearing impairment, autism spectrum disorder, acquired neurological damage, or clinically significant cognitive limitations (e.g., Down Syndrome). In addition, all referring speech-language pathologists were aware of the issue of over-identification of language impairment in bilingual children and worked regularly with bilingual children. Consequently, all considered the presence of language impairment in the children’s L1 as part of their assessment, even if this was done informally, and all were cautious in their interpretations of performance on standardized tests in English, i.e., not relying uncritically on monolingual norm-referencing. We also asked parents about their child’s L1 abilities and developmental history, using the Alberta Language and Development Questionnaire (ALDeQ). Children in the L2-TD group obtained a significantly higher score on this parent interview protocol than children in the L2-DLD group, suggesting that the L2-TD group reached developmental milestones earlier and had higher L1 abilities than children in the L2-DLD group. Further, all children in the L2-DLD group had ALDeQ total scores at least −1.25 standard deviations below the expected mean, which suggests that the child’s L1 development profile is more consistent with children who have DLD (Paradis et al., 2010). The ALDeQ score information is included in Table 1 and acts as a confirmation of the diagnosis of children in the L2-DLD group. Notably, this is the one measure in Table 1 where the groups are not equivalent. For more information about this measure, see the ALDeQ details provided in the Parent Interview section of Section 2.2.

It is worth noting that this sample of children contains an overlapping, but not identical sample, to those in some previous studies (e.g., Paradis et al., 2013; Blom and Paradis, 2015; Govindarajan and Paradis, 2019). Crucially, the previous studies did not consider syntactic development in L2-learning children with DLD and instead focused on other linguistic sub-domains, such as inflectional morphology and narrative structure.

Procedures

Language Samples. Children provided two language samples and were tested either at home or at school by a graduate or senior undergraduate student in the Department of Linguistics at the University of Alberta. One sample was a spontaneous conversation task lasting 15–20 min, where the child conversed with the research assistant. During the conversation, the emphasis was placed on creating a naturalistic conversation with a focus on encouraging the child to talk; research assistants were trained to follow the child’s interests and to ask open-ended follow-up questions. To assist with asking open-ended questions, research assistants were provided with a list of guiding questions that could be used to encourage the child to speak and to elicit detailed responses (e.g., describe a favorite tv show or how to play a favorite game). The second sample consisted of the six stories from the Edmonton Narrative Norms Instrument (ENNI, Schneider et al., 2005). This story-generation narrative task requires children to produce narratives based on wordless picture books. Children are first shown the book in a manner that the research assistant cannot view the pictures. While looking at the book a second time (again, with the pictures out of view of the research assistant), the children told the research assistant the stories. Both the conversation sample and the narrative sample were transcribed using the CHAT system (MacWhinney, 2000; www.childes.psy.cmu.edu). Transcription interrater reliability for the larger corpus from which these data were drawn was 88–97% (Paradis et al., 2017, for details).

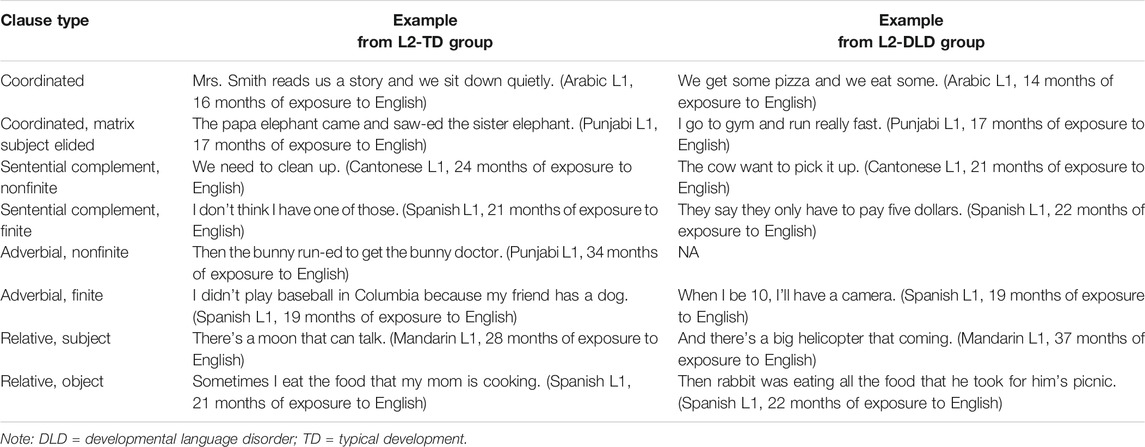

Coding of Complex Syntax. Sentences were extracted from the language sample transcripts and entered into a dataframe. Sentences were defined as an utterance with at least one main verb or a be-copula. This led to a corpus of 10,786 sentences with each child in the L2-TD group contributing an average of 181 sentences (SD = 70.47, range = 69–412) and each child in the L2-DLD group contributing an average of 151 sentences (SD = 35.14, range = 80–217). As a first step, sentences were classified as either simple or complex. Complex sentences were those that had two or more clauses, signaled by at least two main verbs, or one main verb and one be-copula. Next, clauses within the complex sentences were classified for clause type: coordinated clause (COR), sentential complements (SC), adverbial clause (AC), relative clause (RC), and ambiguous (AMB). We included both finite and nonfinite dependent clauses in our tallies and we did not differentiate between them in this study. Ambiguous sentences were those containing two main verbs, indicating that they were attempts at complex sentences, but were difficult to classify, such as and then him jump balloon fly away (L2-TD group, Arabic L1, 18 months of exposure to English). In this example, the child could have been attempting a coordinated clause or an adverbial clause. Additional sample sentences for each clause type can be found in Table 2.

In classifying sentences as simple or complex or in identifying the types of complex clauses, we did not consider if the sentence was grammatically correct. Morphological errors (e.g., him for he, or omission of verbal morphology), as well as lexical choice errors, were not coded. This was decided because our focus was on the production of complex syntax, and not on morphological or lexical accuracy. The presence of morphological and lexical errors did not impede the classification of sentence types, including the ambiguous category. It is also important to note that some complex sentences contained multiple clauses, i.e., more than two clauses. Thus, the tally of each complex clause type was greater than the number of complex sentences overall in this study. For example, consider the utterance if you get a star then you will find a door and then you will get it (L2-TD group, Chinese L1, 20 months of exposure to English). This example was counted as one complex sentence for the main count of complex sentences and, given that it is a three-clause sentence, it was counted once as containing an adverbial for “if you get a star” and once as containing a coordinated clause for “and then you will get it”. A final note about our coding pertains to reliability, for the larger participant sample from which these data were extracted (TD and DLD), coding interrater reliability was 98% for simple sentences and ranged from 86 to 99% for complex sentences (Paradis et al., 2017, for more details).

Parental Interview. Parents participated in an oral interview with a research assistant, with the assistance of an interpreter when needed. Interviews were conducted in the parents’ home. The interviews included a questionnaire on children’s input and experiences with the L1 and the L2 (Alberta Language Environment Questionnaire, ALEQ, Paradis, 2011). For the purposes of this study, responses were used to estimate the child’s overall length of exposure to English (in months). No other information from this questionnaire was included. Parents also completed a second questionnaire, as part of the oral interview, the Alberta Language Development Questionnaire (ALDeQ, Paradis et al., 2010). This questionnaire includes questions about children’s early language milestones, current L1 abilities, behaviour and activity preferences and family history. This questionnaire was designed to assist in assessment with sequential bilingual children (Paradis et al., 2010; Paradis et al., 2013). The scoring system yields a total proportion score between 0 and 1.0, where lower scores indicate delays and difficulties in L1 acquisition as well as possible family history. In this study, the L2-DLD group showed significantly lower ALDeQ scores than the L2-TD group (Table 1).

Vocabulary Task. Children were administered the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test to estimate receptive vocabulary size (PPVT-III, Dunn and Dunn, 1997). For the purposes of this study, the PPVT was used as a measure of general L2 proficiency. We chose to examine general L2 proficiency as part of our sample description because this is important for determining if complex syntax represents a particular area of weakness for children who are learning English as a L2 and who also have DLD. The extent to which the two groups differed on vocabulary was examined when we compared the two groups as part of our group matching process. Notably, we did not explicitly select the children in the L2-TD group to match those in L2-DLD group based on PPVT scores. However, as it turns out, there were no group differences between the L2-TD and L2-DLD groups on this measure (Table 1). The finding of similarity between children with TD and DLD for vocabulary aligns with past findings for monolingual (Gray et al., 1999) and bilingual (Anaya et al., 2018) samples of children.

Results

Our results section is organized into three sections. The first section addresses our first research question, which asked whether there are group differences in the frequency of the sentence types produced by each group when length of exposure to the L2 is taken into consideration. In this section, we present descriptive results of the frequency of sentence types, which are tallied across the narrative and conversation task. We also give the results of linear regression analyses testing whether group membership (L2-DLD or L2-TD) was significantly related to the frequency with which these different sentence types were produced. The second section addresses our second research question, which asked if there were group differences in the overall clausal density and MLU between the L2-DLD and L2-TD group when length of exposure to the L2 is taken into consideration. We also considered whether the observed group difference was greater for clausal density than for MLU. Again, we tallied across the two tasks. We used linear regression to determine if group membership (L2-DLD or L2-TD) was significantly related to children’s clausal density and MLU scores. The last section of the results addresses our third and fourth research questions, which asked: 1) if there were differences in the number of complex sentences produced when children were completing the narrative compared to the conversation task, and if these differences were the same for both the L2-DLD and L2-TD groups; and 2) if there were individual differences in complex syntax use related to age and length of L2 exposure, and if the individual differences were different for the L2-DLD group and L2-TD group. We conducted a series of mixed effect logistic regression analyses where the outcome variable was a binary variable (sentence was simple or complex). In these analyses, task, age and length of L2 exposure were included as fixed effects. Interaction terms were also included for group (L2-DLD or L2-TD) and each of the aforementioned fixed effects. More details about each analysis are provided within each specific section.

Simple and Complex Sentences Across Groups

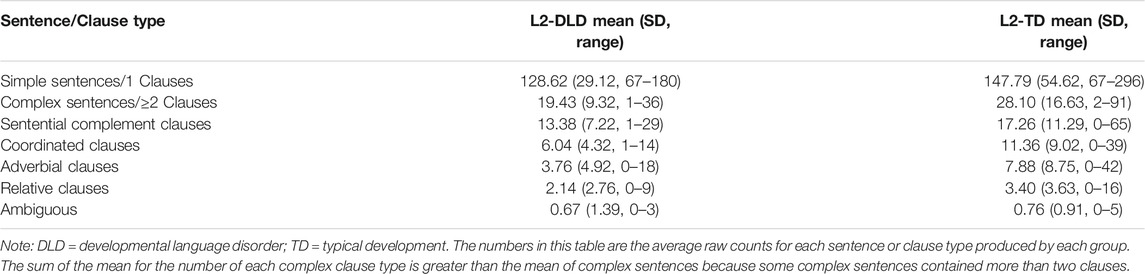

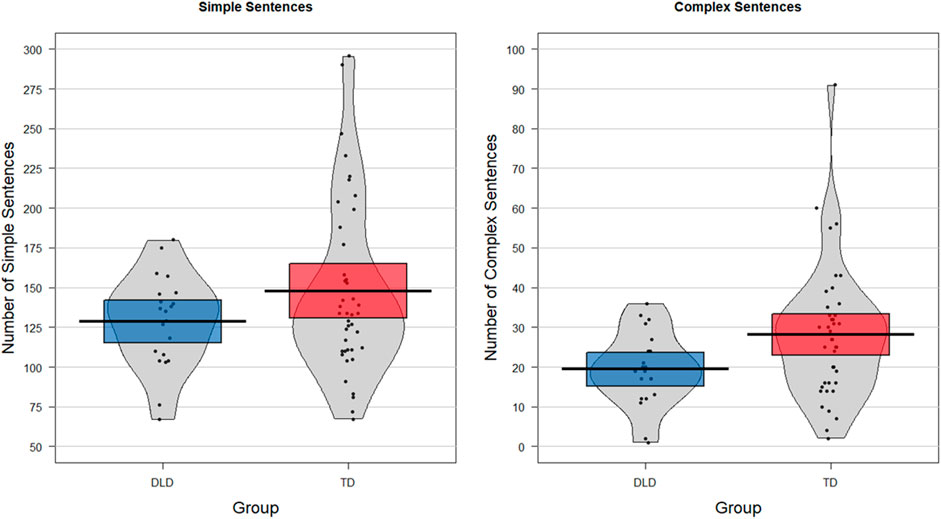

To address research question (1), we first considered the number of simple and complex sentences produced by each group. The tally for simple and complex sentences was done across both tasks and summed to produce a single score for each sentence type. The children in the L2-DLD group produced an average of 128.62 simple sentences and 19.43 complex sentences, thus, 13%, on average, of the utterances produced by children in the L2-DLD group were complex sentences. The children in the L2-TD group produced an average of 147.79 simple sentences and 28.10 complex sentences, thus, 16%, on average, of the utterances produced by children it the L2-TD group were complex sentences. Figure 1 illustrates the use of simple and complex sentences by each group. The average raw counts for simple and complex sentences, along with the average number of each complex clause type (adverbial clauses, relative clauses, sentential complement clauses, coordinated clauses), are provided in Table 3. In inspecting the results in Table 3, it is important to remember that, as described in the Section 2.2, the sum of the complex clause types is greater than the number of complex sentences because some complex sentences contained more than two clauses.

FIGURE 1. The number of simple (A) and complex sentences (B) produced by children in each group across the conversation and narrative task. 1) The scale is different for the two figures, as children produced more simple than complex sentences on the language production tasks; 2) The thick black line represents the median for each group, the colored rectangle is the interquartile range; and the grey shape represents the distribution of all data points, with greater width indicating a higher frequency of data points in that region.

To statistically evaluate if group membership (L2-DLD or L2-TD) was related to the number of simple and complex sentences produced, we conducted linear regression analyses. The first analysis had the number of simple sentences produced as the outcome variable, months of exposure to English (continuous) as a control variable and group membership (categorical) as the variable of interest. The second analysis had the number of complex sentences produced as the outcome variable, months of exposure to English as a control variable and group membership as the variable of interest. We opted to use this regression technique over t-tests to evaluate group differences in the number of sentences produced because past research has suggested that length of exposure to the L2 is a key variable in the development of complex syntax, at least for children with typical language development (Paradis et al., 2017). Thus, it was important to account for the influence of length of L2 exposure when testing for group differences because our study includes children with a range in their length of L2 exposure, even though the groups were matched for average length of L2 exposure.

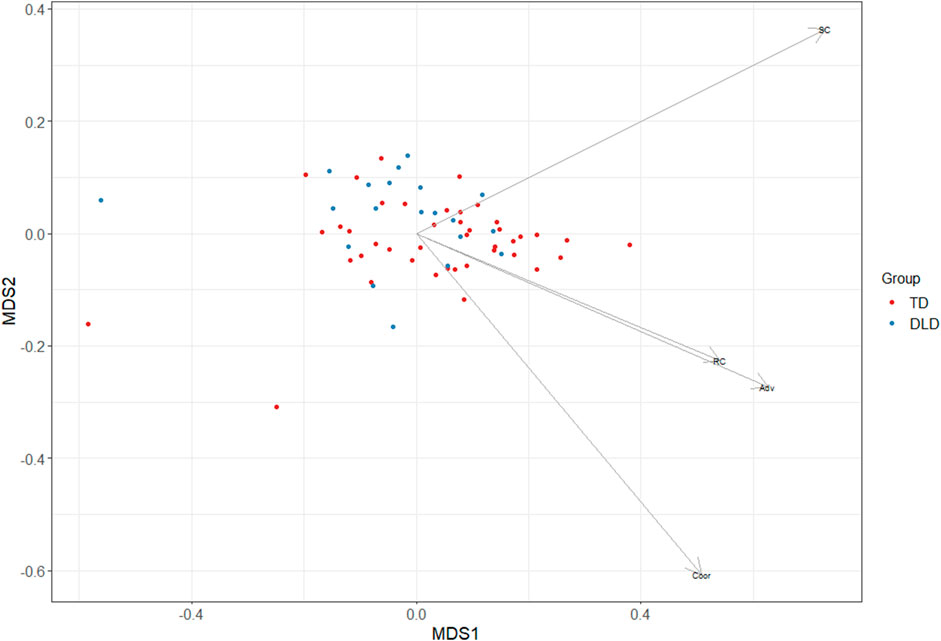

We found that group membership (i.e., L2-DLD or L2-TD) was significantly related to the number of complex sentences that these children produced, but not to the number of simple sentences produced. Table 4 presents the results from the full models which included both group (L2-DLD or L2-TD) as the variable of interest and length of exposure as a control variable. In evaluating these results, we conducted nested model comparisons that compared a model with length of exposure and one without. For simple sentences, the inclusion of exposure did not significantly improve the extent to which the data was explained [F (1) = 0.83, p = 0.67]; however, in the simpler model, group membership remained a non-significant factor in the number of simple sentences produced by children (p = 0.14, from the model without exposure). For complex sentences, the inclusion of exposure resulted in a better model for explaining the data [F (1) = 5.67, p = 0.02]. Linear regression analysis was completed using the base package in R (Version R-3.6.1). Standardized beta coefficients were calculated using the lm. beta package in R and have been included in Table 4 (Behrendt, 2014).

TABLE 4. Linear regression results testing whether group membership is related to the production of simple and complex sentences.

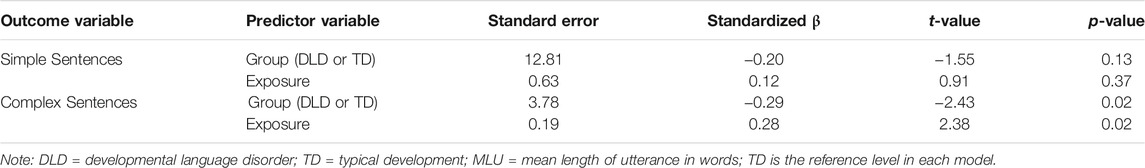

As a next step in examining children’s use of complex sentences, we considered the number of each complex clause type produced by the children in this study. For each complex clause type, we summed across the narrative and conversation task for one combined score. A summary of these counts is provided in Table 3. A visualization of the proportion of these clause types out of the total number of complex clauses by group is provided in Figure 2.

FIGURE 2. Proportion of complex clauses by type and by group. Note: TD = typical development; DLD = developmental language disorder; Coor = coordinated clauses; RC = relatives clause; Adv = adverbial clauses; SC = sentential complement clauses; Ambi = ambiguous clauses.

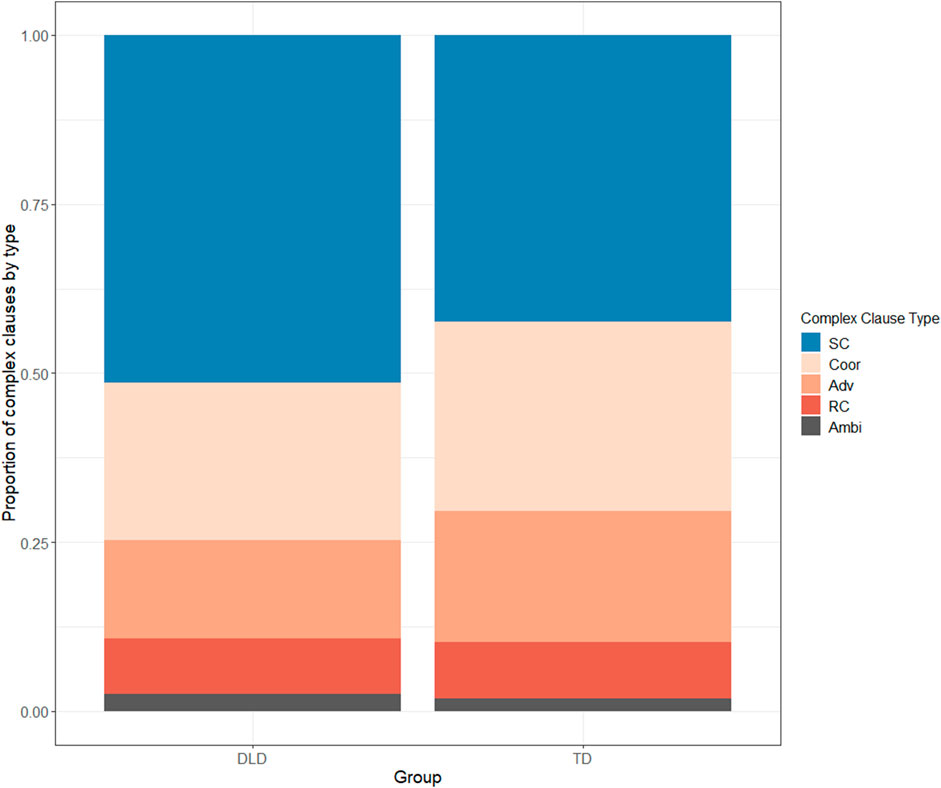

To examine if the distribution of these clause types varied between the L2- DLD and L2-TD groups, we conducted a permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA). PERMANOVA was selected because it is designed for use with count data, like the number of each clause type in this study (Anderson, 2017). The Bray-Curtis index of dissimilarity was used for this analysis. The PERMANOVA results are based on 10,000 permutations. This analysis was completed using the vegan package in R (Oksanen et al., 2020). The PERMANOVA results converge with that of the linear regression results above, suggesting that the production of complex syntax is significantly different between the L2-TD and L2-DLD groups [F (1) = 2.34, p = 0.05]. Figure 3 illustrates the extent to which each clause type is influencing this main effect. This figure is based on multidimensional scaling (MDS), in this case non-metric scaling. In trying to conceptualize each MDS, it can be helpful to note that each MDS is conceptually similar to the principal components in a principal components analysis. Thus, each MDS is a mathematical combination of the four complex clause types into two dimensions. The positioning and direction of the arrows indicate the extent to which each of the four complex clause types included in the analysis pattern together in determining the relative distance between observations. Thus, Figure 3 illustrates that coordinated, relative and adverbial clauses pattern together within this data set. Sentential complement clauses are distinct from these other sentence types. Furthermore, the slight downward trend among the points, representing the complex syntax use of children within the L2-TD group (the red points), suggest that the collection of coordinated, adverbial and relative clauses are particularly relevant for understanding differences in the production of complex sentences between the L2-TD and L2-DLD groups. Interestingly, despite these differences, the ranking of the most frequent to least frequent clause type was the same for both groups: sentential complement clauses > coordinated clauses > adverbial clauses > relative clauses.

FIGURE 3. PERMANOVA results for complex clause type. Notes: MDS1 = Multidimensional scaling ordinate 1; MDS2 = Multidimensional scaling ordinate 2; TD = typical development; DLD = developmental language disorder; Coor = coordinated clauses; RC = relatives clause; Adv = Adverbial clauses; SC = sentential complement clause.

Clausal Density and MLU Across Groups

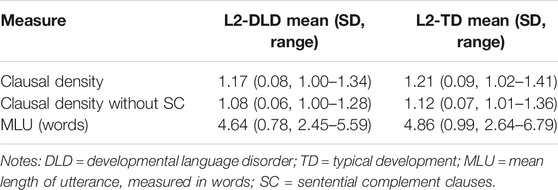

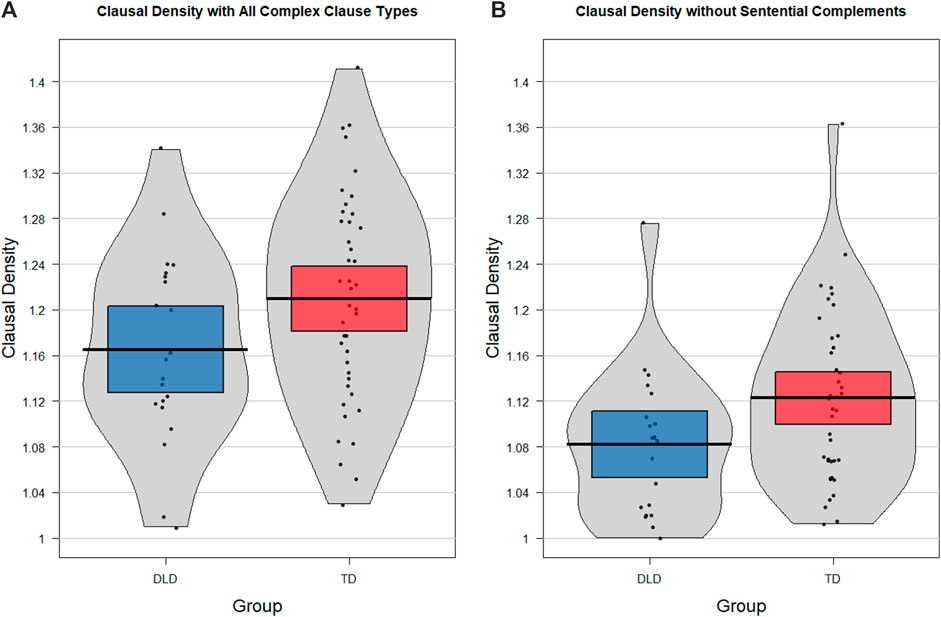

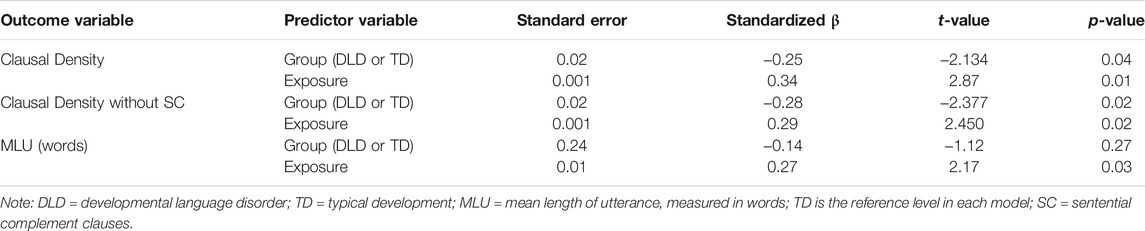

To further investigate complex sentence use, we examined children’s use of complex sentences using two additional measures of syntax: 1) clausal density and 2) mean length of utterance (MLU). Clausal density was tallied across the conversation sample and the narrative task, as a ratio of the total number of clauses divided by the total number of sentences (cf. Frizelle et al., 2018). We calculated this ratio by adding the total number of clauses [which included simple sentences, the main clause within complex sentences and all additional clauses (embedded and coordinated) within the complex sentences]. This total was then divided by the number of sentences to yield a clausal density score for each child. In this way, a score of 1.0 indicates that the child produced only simple sentences. We calculated two clausal density scores, one that included sentential complement clauses and one that excluded this complex clause type. This second clausal density score was tallied because of the results of the PERMANOVA, which suggested coordinated, adverbial and relative clauses might be particularly relevant for differentiating between L2-TD and L2-DLD. MLU was counted in words across the two tasks. MLU was calculated in CLAN for all the utterances in each child’s language sample, following the usual procedures (MacWhinney, 2000). Table 5 presents the clausal density scores (with and without sentential complement clauses), as well as the MLU scores, by group.

To statistically evaluate if children in the L2-DLD group showed differences in these measures compared to the L2-TD group, we conducted three linear regression analyses (one with clausal density with sentential complement clauses, one with clausal density without sentential complement clauses, and one with MLU as the outcome variables). For each analysis, there were two predictor variables: months of exposure to English (continuous) was a control variable and group membership (categorical) was the variable of interest. As was the case for our analysis of simple and complex sentence counts, we opted to use this regression technique over t-tests to evaluate group differences for these measures because past research has suggested that length of exposure to the L2 is a key individual difference variable in the development of complex syntax, at least for children with typical language development (Paradis et al., 2017). This set of regression analyses indicated that the L2-TD group produced utterances with a higher clausal density than the L2-DLD group (Figure 4). Clausal density calculated without sentential complements yielded somewhat greater group differences, as shown by the model results in Table 6 and the visualization in Figure 4. There was no significant difference in the MLU between these two groups, which is expected given how similar the means were for this measure. Table 6 presents the results from the full models which included both group (L2-DLD or L2-TD) as the variable of interest and length of exposure as a control variable. In evaluating these results, we conducted nested model comparisons that compared a model with length of exposure and one without. The inclusion of exposure resulted in better models for explaining these data (for clausal density with sentential complement clauses, F (1) = 8.15, p = 0.006; for clausal density without sentential complement clauses, F (1) = 6.00, p = 0.02, and for MLU, F (1) = 4.70, p = 0.03).

FIGURE 4. Clausal density by group. The clausal density measure in the (A) was calculated across all complex clause types, whereas, sentential complement clauses were omitted from the clausal density measure in the (B). Note: The thick black line represents the median for each group, the colored rectangle is the interquartile range; and the grey shape represents the distribution of all data points, with greater width indicating a higher frequency of data points in that region.

TABLE 6. Linear regression results testing whether group membership is related to clausal density and MLU.

Sources of Individual and Task-Based Differences

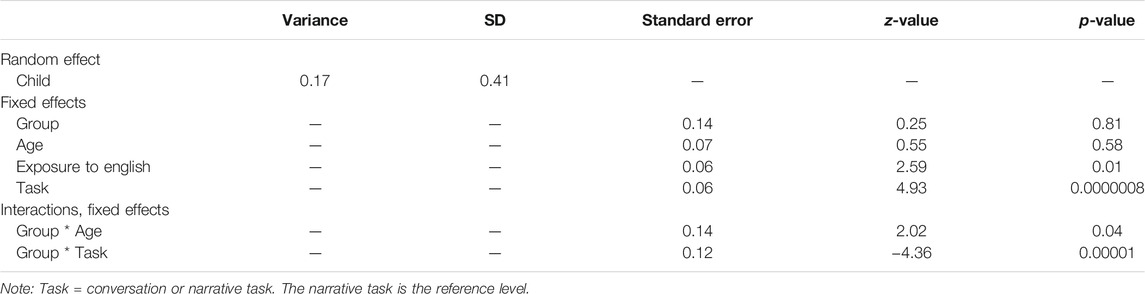

To investigate sources of individual and task differences in complex sentence use, we conducted mixed effect logistic regression analyses. This technique was chosen because it has several advantages. One advantage is robustness, which is especially important in this case where we have unequal observations between groups and small samples (Baayen, 2008). An additional benefit is that mixed effect models allow for random variation inherent within the sample to be incorporated into the analysis. That is, each participating child has unknown properties that will influence their performance in any study. Accordingly, it is preferred to account for this random variation by including random effect variables in the analysis. In this study, we included child as a random effect in all models. The outcome measure was a binary variable: whether the sentence was simple (false) or complex (true). Models were created using the lme4 package in R (Bates et al., 2019).

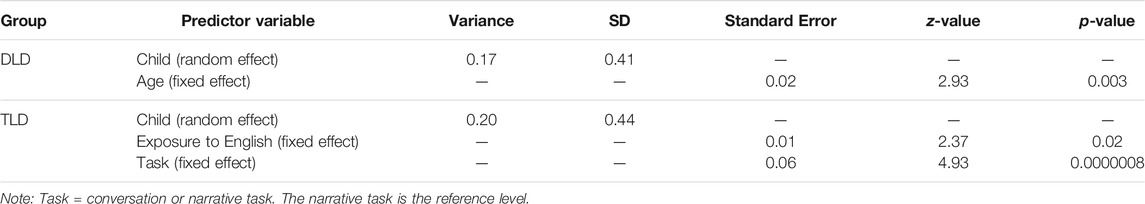

We started with a data frame that included both the L2-TD and L2-DLD children. Child was the model random effect, and the fixed effects were group (L2-TD or L2-DLD), task (narrative or conversation), L2 exposure in months (continuous) and age in months (continuous). Because previous research has suggested that individual difference factors may not influence L2 development for children with DLD in the same manner as has been observed for children with TD (e.g., Blom and Paradis, 2015), we also included interaction terms in our model. Specifically, we included an interaction term for Group and each of the other fixed effect variables. This analysis revealed a significant interaction between task (narrative/conversation) and group (DLD or TD), which suggested a stronger influence of task for the L2-TD group than the L2-DLD group. There was also a significant interaction for age and group (DLD or TD), which suggested that age was a stronger influence in complex syntax use for the L2-DLD group than the L2-TD group. There was no significant interaction between exposure to English and Group (DLD or TD) (p = 0.67) and, accordingly, this interaction was dropped from the reported model. The results of this analysis are presented in Table 7.

TABLE 7. Logistic regression results examining individual differences in complex syntax use with the full sample combined and where the outcome variable was a binary variable (simple or complex sentence).

Given the interactions, we opted to follow up by modeling each group separately to determine the sources of individual differences and task effects for each group. For each of the separate analyses, we started with a full model that overfit the data and used the technique of backwards elimination to remove predictors that were not significant in a stepwise fashion. The fixed effect variables were task (narrative or conversation), L2 exposure in months (continuous) and age in months (continuous). The results of this logistic regression analyses are presented in Table 8. Results showed that the L2 children with DLD were more likely to use complex sentences if they were older. When modelled separately from the L2-TD group, exposure to English and task were not significantly related to complex syntax use within the L2-DLD group. In contrast, the L2 children with TD were more likely to use complex sentences if they had been learning English longer and were completing the conversation as opposed to the narrative task. When modelled separately from the L2-DLD group, age was not significantly related to complex syntax use within the L2-TD group.

TABLE 8. Logistic regression results examining individual differences in complex syntax use with one model for L2-DLD and one model for L2-TD where the outcome variable was a binary variable (simple or complex sentence).

Discussion

Over-identification of language disorder among bilingual children with TD is a risk factor in assessment. One strategy for improving assessment accuracy with bilingual children is to determine which linguistic subdomains are areas of particular weakness for bilingual children with DLD, in reference to their TD bilingual age peers. Therefore, in this study we sought to determine if the use of complex sentences in naturalistic production could potentially differentiate between school-age sequential bilinguals with TD and with DLD at the early stages of L2 acquisition. The rationale for examining complex sentences was based on the relative strength of this subdomain, compared to morphology, in English L2 acquisition of TD bilinguals on one hand, and the relative weakness of this subdomain for monolinguals with DLD on the other. Following Scheidnes and Tuller (2019), we hypothesized that complex syntax could be a likely domain for identifying differences between bilingual typical and atypical learners. Accordingly, 63 English L2 children aged 5–7 years with TD and DLD were administered a conversation and narrative task. The L2-TD and L2-DLD groups were matched for age, length of L2 exposure and general L2 proficiency (receptive vocabulary size). Language samples from both tasks were coded and analyzed for the use of complex versus simple sentences, for the distribution of complex sentence types, for clausal density and MLU. Task type, as well as age and L2 exposure, were examined as sources of individual differences.

Comparing the Use of Complex Sentences Between L2-TD and L2-DLD

Regarding our first research question, in combined data from both tasks, differences were found between L2 children with TD and with DLD for production of complex sentences; namely, the L2-TD group used more complex (multi-clause) sentences than the L2-DLD group, whereas, the groups did not differ in their use of simple (single clause) sentences. The relative frequency of complex clause types was similar between the groups; specifically, frequency of use was in the following order: sentential complements > coordinated clauses > adverbial clauses > relative clauses (Table 3 and Figure 2). However, the PERMANOVA analysis showed that the use of coordinated clauses, adverbial clauses and relative clauses patterned together in complex syntax use, and that these clause types may be particularly important for understanding between-group differences. In contrast, sentential complement clauses were shown to be distinct from the other complex clause types, and to be less important for understanding between-group differences. As it turned out, production of sentences with sentential complement clauses did not differ substantially between these groups. This is evidenced by examining the clausal density measures. There were larger group differences between the L2-TD and L2-DLD groups for mean clausal density excluding sentences with sentential complement clauses compared to mean clausal density including all four complex sentence types (Table 6 and Figure 4).

These results indicate that there are parallels between monolinguals and bilinguals with TD and DLD in that the production of complex sentences is an area of weakness for school-age children with DLD, whether English is their L1 or L2. Furthermore, Marinellie (2004) found that monolingual school age children with DLD were able to produce a full range of complex sentences, but they used them less frequently than their TD peers. In this study of child L2 speakers, we also found that children with DLD appeared to have acquired the different complex sentence types, but did not use them as often in naturalistic language production. Marinellie (2004) suggests that this might point to processing deficits, as opposed to syntactic representation deficits, as the source of the problem for children with DLD. Future research is needed to understand this further. Finally, with respect to the frequency distribution of different complex clause types, the order is similar to what has been reported for preschool monolingual English children (Diessel, 2004; Vasilyeva et al., 2008). However, it is slightly dissimilar to what has been reported for school-age monolingual English children, for whom coordinated clauses are the most frequent type, and not sentential complement clauses (Frizelle et al., 2018).

Marinellie (2004) found that, for school age monolinguals, adverbial, coordinated and relative clauses differentiated between TD and DLD, but not other complex sentence types. Also, Eisenberg (2004) found few differences between monolinguals with TD and DLD for sentential complement clauses in naturalistic production. The present study also found that production of sentential complement clauses was more similar between L2-TD and L2-DLD; whereas, the production of adverbial, coordinated and relative clauses showed greater group differences (Figures 3, 4 and Table 6). This raises the question of why sentential complement clauses would be distinct from other complex clause types, and what underlying feature characterizes the complex sentences that differentiate best between children with TD and children with DLD. Regarding frequency of sentential complement clauses in production, this could mirror frequency in the input, although this observation is based on caregiver speech to young children (Diessel, 2004). Unlike coordinated, adverbial and relative clauses, many sentential complement clauses are part of the verb argument structure, so might be acquired along with the verb. By contrast, coordinated, adverbial and relative clauses are generated independently of verb argument structure, and thus, are purely syntax. In addition, sentential complement clause use could be inflated by use of frames like “he said that + S”, or “I want to + V”, which are frequent in the input and might be less than fully productive at this stage in their L2 development; in other words, they might be partially unanalyzed phrases. Diessel (2004) found that, for monolingual preschoolers, sentential complements were the first complex sentences to emerge, but that 81% of these were based on just six highly frequent verb frames. Taken together, these explanations could mean that sentential complement clauses are not as indicative of a child’s syntactic abilities as the other complex clause types.

In sum, our analyses yield an affirmative answer to our first research question: the frequency of complex sentence types produced does differ between L2-TD and L2-DLD. It is important to note that the groups in this study were matched for L2 receptive vocabulary size and showed no significant differences in MLU; thus, the group differences found were specific to the use of complex sentences and complex clause types and not attributable to general English L2 proficiency. Despite the significant differences between the L2-TD and L2-DLD groups, there was still a great deal of overlap in the use of complex sentences among individual children in both groups (Figure 1), which could limit the potential for differentiation between bilinguals with TD and with DLD based on language sample comparison alone. We return to this issue in Section 4.4.

Comparing Clausal Density and MLU Between L2-TD and L2-DLD

Our second research question concerned a comparison between mean clausal density and MLU. The present study found that, for school-age bilinguals in their L2, there were significant group differences between TD and DLD for clausal density but not for MLU. Akin to Frizelle et al. (2018), these findings indicate that clausal density and MLU do not measure identical constructs. Recall that MLU and clausal density measure different aspects of morphosyntactic development. MLU is more general and includes sentence length expansion through the use of adjective, adverb and prepositional phrases; whereas, clausal density is specific to multi-clause sentences through coordination and embedding. One contributing factor to the outcome for MLU could be that, for both TD and DLD, overlap in the omission of unbound grammatical morphemes is high in the early stages of L2 acquisition (Paradis et al., 2021), possibly higher than for use of complex sentences. Because MLU includes both syntax and morphology, unlike clausal density, this could make the latter superior in its potential to discriminate between sequential bilinguals with TD and those with DLD.

Influence of Task, Age and L2 Exposure

Our logistic regression analyses revealed that task effects on individual performance emerged for L2-TD but not for L2-DLD (Tables 7, 8). Recall that this analysis was not based on clausal density, but instead, the model included a binary dependent variable, e.g., whether each sentence was complex, true or false, for each child. Thus, L2-TD children tended to produce more complex sentences during the conversation task than the narrative task, but the L2-DLD children’s production of complex sentences was less sensitive to task. That the TD children produced more complex sentences on the less demanding production task contrasts with previous studies with monolingual adolescents (Nippold et al., 2008; Nippold et al., 2014) and simultaneous bilinguals (Cahill et al., 2020). This contrast could be due to age and L2 proficiency. The bilinguals in this study were young children at the early stages of L2 acquisition. Perhaps these L2-TD children have more experience with English conversation than English narratives, therefore, this task more accurately measures the peak of their proficiency at this point in their development. Perhaps the low sensitivity to task for L2-DLD is a reflection of their greater difficulties with complex syntax; in other words, they have not yet developed sufficient proficiency with L2 complex syntax to be sensitive to differences in task demands. If this explanation is on the right track, then, as bilingual children mature and develop proficiency in their L2, more demanding tasks might prompt more production of complex sentences, especially among L2-TD groups of children, which may assist in differentiating between L2-TD and L2-DLD.

The L2-TD and the L2-DLD participants were groupwise matched for age and length of L2 exposure; however, there was still variation within each group (Table 1). Our analyses revealed that older children in the L2-DLD group produced more complex sentences than younger children, but this effect did not emerge for L2-TD. Conversely, children in the L2-TD group who had longer exposure to the L2 produced more complex sentences, but this was not the case for L2-DLD. This pattern of age being a prominent individual difference factor for bilinguals with DLD, while input factors being more prominent for bilinguals with TD is consistent with other studies (Blom and Paradis, 2015; Govindarajan and Paradis 2019). On one hand, this is not surprising because there is overlap in the participant samples between these studies and the present study. On the other hand, each study examined a different linguistic subdomain. Blom and Paradis (2015) examined sources of individual variation on an elicitation task with verb morphology and Govindarajan and Paradis (2019) examined sources of individual differences with narrative macrostructure and microstructure components (not including syntactic complexity). Taken together, all three studies show that, across multiple linguistic subdomains, bilinguals with DLD show less sensitivity to quantity of input in the L2 than their TD peers in their development. A possible reason for this is that children with DLD’s uptake from the available input is limited due to verbal memory and processing deficits (Leonard, 2014; Blom and Paradis, 2015). Additional research on the sources of individual differences in bilingual children with DLD needs to be conducted with different participant samples to further investigate this possibility.

Clinical Implications and Limitations

Clausal density scores from language production samples were found to differ between English-L2 bilingual school-age children with DLD and those with TD, while MLU scores were not. Also, clausal density based on coordinated clauses, adverbial clauses and relative clauses (not sentential complement clauses) revealed a larger separation between the children with DLD and those with TD. These findings suggest that production of certain complex sentence/clause types has the potential to be useful in differentiating between bilingual children with typical from atypical development in the early stages of L2 acquisition. However, a limitation of this study is that it is based on between-group comparisons and did not include more clinically focussed analyses such as, determination of specificity and sensitivity or calculation of likelihood ratios.

The overlap between the L2-TD and L2-DLD groups in Figure 4 indicates it is unlikely that clausal density from a language sample, in isolation, would achieve identification of DLD with adequate sensitivity and specificity. It is possible that clausal density from a language sample would need to be combined with other assessment measures suitable for bilinguals in order to achieve comprehensive and accurate assessment (cf. Paradis et al., 2013; Paradis, 2016; Paradis et al., 2021). It is also possible that abilities with complex syntax could be probed using a task other than language sampling to achieve adequate discrimination potential. Many speech-language pathologists do not have the time to gather, transcribe and code language samples (cf. Cahill et al., 2020). In contrast to language sampling, sentence repetition tasks are more convenient as a measure of morphosyntactic abilities. Studies show that sentence repetition tasks function well to discriminate TD from DLD among bilinguals (Armon-Lotem and Meir, 2016; Meir et al., 2016). The naturalistic data from this study provides evidence supporting the inclusion of complex sentences with coordinated clauses, adverbial clauses and relative clauses on such tasks designed for assessment with bilinguals. Overall, additional research is needed to determine how the weakness with complex syntax shown by bilinguals with DLD could be harnessed effectively in tools for assessment.

While sentence repetition tasks may be more efficient in assessment, naturalistic production tasks have the advantage in that they can reveal possible targets for intervention with children diagnosed with DLD. Complex syntax is a component of CALP—cognitive academic language proficiency (Cummins, 2000; NASEM, 2017) and bilingual students can take up to 5–7 years in school to converge with their monolingual classmates for CALP (Soto-Corominas et al., 2020). As mentioned earlier, Fletcher and Frizelle (2017) suggested that difficulties in the acquisition of complex syntax could underlie the weaker academic outcomes of monolingual children with DLD (Fletcher and Frizelle, 2017). Therefore, complex syntax would be a logical target for intervention with school-age bilingual children with DLD; doing so could be of benefit not only to their oral language development but also to their academic achievement.

Data Availability Statement

The data analyzed in this study is subject to the following licenses/restrictions: We do not have permission from the participants’ parents to share the data from this study on a publicly accessible website. This is because data were collected from 2006–2009, and requesting such permission was not part of the standard consent for participation form. Requests to access these datasets should be directed to jparadis@ualberta.ca.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Research Ethics Board, University of Alberta. Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardian/next of kin.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the conceptualization and design of this study. BR designed the coding system for the language samples and supervised the coding, with assistance from TD and JP. Raw data for this study were provided by JP. ST conducted some preliminary analyses and literature review for the manuscript and assisted with coding. JP wrote the preliminary Introduction and Discussion sections of the manuscript. TD conducted the statistical analyses and wrote the preliminary Methods and Results sections. Both JP and TD contributed to the writing in the submitted version of this manuscript.

Funding

This research was financially supported through funding from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (standard research grant # 410-2010-0123 to JP).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to the families for welcoming us into their homes and participating in this research. We would like to thank the Multicultural Health Brokers Cooperative in Edmonton, Canada for assisting in designing the questionnaire, providing cultural brokering and interpretation services, and supporting recruitment. We would also like to express our appreciation of the Edmonton Public School Board and the Toronto Catholic District School Board for their help in participant recruitment. We also acknowledge the dedicated work of our research assistants, Khadija Farooq, Nicole Salvador and Julie Sawchuk for their excellent work in coding the data. We are also grateful to Preston Sorenson for consulting on the statistical analyses.

References

Altman, C., Armon-Lotem, S., Fichman, S., and Walters, J. (2016). Macrostructure, Microstructure, and Mental State Terms in the Narratives of English-Hebrew Bilingual Preschool Children with and without Specific Language Impairment. Appl. Psycholinguist. 37, 165–193. doi:10.1017/S0142716415000466

Anaya, J. B., Peña, E. D., and Bedore, L. M. (2018). Conceptual Scoring and Classification Accuracy of Vocabulary Testing in Bilingual Children. Lang. Speech Hear. Serv. Sch. 49 (1), 85–97. doi:10.1044/2017_LSHSS-16-0081

Anderson, M. J. (2017). “Permutational Multivariate Analysis of Variance (PERMANOVA),” in Wiley StatsRef: Statistics Reference Online (John Wiley & Sons), 1–15. doi:10.1002/9781118445112.stat07841

Armon-Lotem, S., Meir, N., De Houwer, A., and Ortega, L. (2019). “The Nature of Exposure and Input in Early Bilingualism,” in The Cambridge Handbook of Bilingualism. Editors A. De Houwer, and L. Ortega (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press), 193–212.

Armon-Lotem, S., and Meir, N. (2016). Diagnostic Accuracy of Repetition Tasks for the Identification of Specific Language Impairment (SLI) in Bilingual Children: Evidence from Russian and Hebrew. Int. J. Lang. Commun. Disord. 51, 715–731. doi:10.1111/1460-6984.12242

Baayen, R. H. (2008). Analyzing Linguistic Data: A Practical Introduction to Statistics Using R. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Bates, D., Maechler, M., and Bolker, B. (2019). Linear Mixed-Effects Models Using ‘Eigen’ and S4. R Package.

Blom, E., and Paradis, J. (2015). Sources of Individual Differences in the Acquisition of Tense Inflection by English Second Language Learners with and without Specific Language Impairment. Appl. Psycholinguist. 36, 953–976. doi:10.1017/S014271641300057X

Cahill, P., Cleave, P., Asp, E., Squires, B., and Kay‐Raining Bird, E. (2020). Measuring the Complex Syntax of School‐aged Children in Language Sample Analysis: A Known‐groups Validation Study. Int. J. Lang. Commun. Disord. 55 (5), 765–776. doi:10.1111/1460-6984.12562

Chondrogianni, V., and Marinis, T. (2011). Differential Effects of Internal and External Factors on the Development of Vocabulary, Tense Morphology and Morpho-Syntax in Successive Bilingual Children. Lab 1, 318–345. doi:10.1075/lab.1.3.05cho

Cummins, J. (2000). Language, Power and Pedagogy: Bilingual Children in the Crossfire. Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters.

Diessel, H. (2004). The Acquisition of Complex Sentences. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press.

Dunn, L. M., and Dunn, D. M. (1997). Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test. 3rd Edition. Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Service.

Eisenberg, S. (2004). Production of Infinitives by 5-Year-Old Children with Language-Impairment on an Elicitation Task. First Lang. 24, 305–321. doi:10.1177/0142723704045679

Fletcher, P., and Frizelle, P. (2017). “Syntax in Child Language Disorders,” in Handbook of Child Language Disorders (New York: Routledge), 416–440. doi:10.4324/9781315283531-17

Frizelle, P., and Fletcher, P. (2014). Relative Clause Constructions in Children with Specific Language Impairment. Int. J. Lang Commun. Disord. 49, 255–264.

Frizelle, P., Thompson, P. A., McDonald, D., and Bishop, D. V. M. (2018). Growth in Syntactic Complexity between Four Years and Adulthood: Evidence from a Narrative Task. J. Child. Lang. 45, 1174–1197. doi:10.1017/S0305000918000144

Govindarajan, K., and Paradis, J. (2019). Narrative Abilities of Bilingual Children with and without Developmental Language Disorder (SLI): Differentiation and the Role of Age and Input Factors. J. Commun. Disord. 77, 1–16. doi:10.1016/j.jcomdis.2018.10.001

Gray, S., Plante, E., Vance, R., and Henrichsen, M. (1999). The Diagnostic Accuracy of Four Vocabulary Tests Administered to Preschool-Age Children. Lang. Speech Hear. Serv. Sch. 30 (2), 196–206. doi:10.1044/0161-1461.3002.196

Hesketh, A. (2004). Grammatical Performance of Children with Language Disorder on Structured Elicitation and Narrative Tasks. Clin. Linguist. Phon. 18, 161–182. doi:10.1080/02699200310001659061

Kay-Raining Bird, E., Trudeau, N., and Sutton, A. (2016). Pulling it All Together: The Road to Lasting Bilingualism for Children with Developmental Disabilities. J. Commun. Disord. 63, 63–78. doi:10.1016/j.jcomdis.2016.07.005

Kover, S. T., and Atwoo, A. K. (2013). Establishing Equivalence: Methodological Progress in Group-Matching Design and Analysis. Am. J. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 118, 3–15. doi:10.1352/1944-7558-118.1.3

MacKay, E., Lynch, E., Sorenson Duncan, T., and Deacon, S. H. (2021). Informing the Science of Reading: Students' Awareness of Sentence‐Level Information Is Important for Reading Comprehension. Read. Res. Q. 56, S221–S230. doi:10.1002/rrq.397

MacWhinney, B. (2000). The CHILDES Project: Tools for Analyzing Talk: Transcription Format and Programs. 3rd ed. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum. Available at: www.childes.psy.cmu.edu.

Marinellie, S. A. (2004). Complex Syntax Used by School-Age Children with Specific Language Impairment (SLI) in Child-Adult Conversation. J. Commun. Disord. 37, 517–533. doi:10.1016/j.jcomdis.2004.03.005