Challenges for Optimizing Real-World Evidence in Alzheimer’s Disease: The ROADMAP Project

Abstract

ROADMAP is a public-private advisory partnership to evaluate the usability of multiple data sources, including real-world evidence, in the decision-making process for new treatments in Alzheimer’s disease, and to advance key concepts in disease and pharmacoeconomic modeling. ROADMAP identified key disease and patient outcomes for stakeholders to make informed funding and treatment decisions, provided advice on data integration methods and standards, and developed conceptual cost-effectiveness and disease models designed in part to assess whether early treatment provides long-term benefit.

INTRODUCTION

In Alzheimer’s disease (AD), monitoring of patient outcomes is key to mapping disease progression, establishing the effectiveness and safety of interventions, and optimizing disease management. However, this is challenging in a real-world context as, unlike in clinical trials, data on clinical and patient-reported outcomes are not consistently collected in routine clinical practice post diagnosis, and there is little consensus on which outcomes to collect [1]. As AD onset may precede symptoms by many years [2, 3], measures informing early detection and disease progression are also required to develop treatments targeting preclinical disease.

Using real-world evidence (RWE) to demonstrate the value of early interventions is becoming increasingly important, as a treatment benefit may not be realized until later in the disease course and may be difficult to capture in trials shorter than 5 years [4, 5]. Synthesis of data, including broad-based national population electronic health records (EHRs) and in-depth research data from population and clinical cohorts, and modeling of the effect of early treatment on long-term clinical outcomes in real-world datasets, can provide effectiveness and cost evidence to help decision-makers assess the value of new disease-modifying treatments. This evidence and other evidence from real-world data can also be used to inform other aspects of AD research and clinical practice, such as public health (e.g., primary and secondary prevention) and the evaluation of non-pharmacological interventions. Nevertheless, the utility of RWE approaches varies considerably, with most studies being underpowered due to limited data access, sample size and length and frequency of follow-up. Also, generalizability is constrained by the diversity of outcomes.

For AD, there is added complexity due to a lack of consensus on standardized outcomes for longitudinal observational studies, poor transferability of outcome measures across studies and across medical and social care systems, and a lack of relevant AD-related cognitive and functional measures that are applicable across the disease spectrum. How best to model the natural history of AD using real-world data is also unclear: disease modeling is particularly challenging because the association of changes in cognition, function, and behavior with disease progression is uncertain [6, 7].

Incorporating the assessment of AD-related outcomes into real-world settings requires consensus between stakeholders. RWE helps to inform regulators (on treatment patterns, effectiveness, and risk); payers, Health Technology Assessment (HTA) bodies, and healthcare providers (HCPs; on economic value/resource utilization, clinical effectiveness relative to current standard-of-care treatments, and patient-relevant outcomes, including quality of life [QoL]); industry (on product effectiveness and safety, research and development, pricing, and manufacturing); and scientists (on mechanisms and diagnostic/treatment pathways) to accelerate decision-making on new and existing treatments [8– 10].

Innovative Medicines Initiative (IMI) projects, such as the European Medical Information Framework (EMIF) [11] (http://www.emif.eu) and the European Prevention of Alzheimer’s Dementia (EPAD) project [12] (http://ep-ad.org/), partly address the problems of combining different types of data and identifying at-risk individuals before symptoms develop. However, no large-scale international projects have provided a framework for mapping and linking AD progression to QoL and resource utilization across the RWE spectrum. This article overviews the aims, objectives, methods, and deliverables of the ROADMAP (Real world Outcomes across the AD spectrum for better care: Multi-modal data Access Platform) project, which was undertaken to address these and other limitations. Findings of ROADMAP are not presented here but will be published in the future.

WHAT IS ROADMAP?

ROADMAP is a public-private advisory partnership to evaluate the usability of multiple RWE data sources in the decision-making process for developing new treatments in AD (http://roadmap-alzheimer.org). This two-year research project was recently completed and was funded through IMI2, Europe’s largest public-private initiative to accelerate new drug development. IMI2 partners the European Union’s (EU) Horizon 2020 program (https://ec.europa.eu/programmes/horizon2020/) with the European pharmaceutical industry, represented by the European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industries and Associations (EFPIA; https://www.efpia.eu). The IMI2 design facilitates collaboration between regulatory bodies, payers, patient organizations, pharmaceutical companies, academia, and other important stakeholders. Indeed, the ROADMAP consortium includes 26 partners: 12 European academic institutions, nine pharmaceutical companies from Europe and the USA, one regulatory body, one HTA body, one patient organization, one technology enterprise, and one research service company (http://roadmap-alzheimer.org/partners/). This broad stakeholder base is essential to establish a sustainable consensus on how to apply RWE to optimally benefit patients, and to better prepare healthcare, social care, and data systems for emerging new treatments.

ROADMAP AIMS, OBJECTIVES, METHODS, AND DELIVERABLES

Aims and objectives

ROADMAP aimed to evaluate the feasibility and utility of an integrated data environment for RWE in AD by evaluating disease progression and health economic models. ROADMAP developed, tested, and will advise on: consensus-based key disease and patient outcome measures endorsed by stakeholder groups for making informed funding and treatment decisions; data integration tools for dataset characterization and outcome classification, data sourcing, data standards, and a software application repository; guidelines on the handling and interpretation of RWE data; and ideal specifications for disease and cost-effectiveness models. In parallel, tools for stakeholder engagement were developed, the usability of RWE to demonstrate the economic value of new AD treatments was evaluated, and the critical ethical, legal, and social barriers to using RWE in AD were mapped.

Table 1 summarizes the ROADMAP objectives, administered through eight Work Packages (WPs).

Table 1

ROADMAP objectives

| Project management and coordination |

| Establish a project management and governance structure to deliver the project to plan, and within time and budget; to ensure effective communication between consortium members; and to develop a plan for phase 2 of the ROADMAP initiative (WP1) |

| Outcome definition |

| Define and catalog outcomes across the spectrum of AD, prioritize these from the perspective of the different stakeholders, and assess the availability of data from real-world data sources on these outcomes (WP2) |

| Data integration |

| Identify and pool AD-related RWE data and establish solutions for how to combine different RWE sources with RCT data supporting pharmacoeconomic evaluation (WP3) |

| Disease modeling and simulation |

| Develop and validate a core disease progression model combining diverse datasets, facilitating analysis of disease trajectories and the effect of interventions on disease trajectories (WP4) |

| Economic modeling |

| Identify the specific data and analytical methods required to develop a robust state-of-the-art cost-effectiveness model capable of evaluating AD interventions that meet the needs of regulators, payers, HTA agencies, service providers, caregivers, and industry (WP5) |

| HTA and regulatory engagement |

| Develop guiding principles and recommendations from regulators/payers/HTA agencies for the development and incorporation of RWE into clinical and market-access development plans for AD (WP6) |

| Patient and clinical engagement |

| Develop and implement a communication strategy focusing on the needs of patients and healthcare professionals (WP7) |

| Ethical, legal, and social implications |

| Map the critical ethical, legal, and social issues that arise from creating an RWE platform, reusing existing health data and pooling data from different data sources (WP8) |

AD, Alzheimer’s disease; HTA, health technology assessment; RCT, randomized controlled trial; RWE, real-world evidence; WP, Work Package.

Methods

ROADMAP explored the integration of evidence from broad-based national population EHRs with in-depth cohort data and tightly-focused RCT data. This approach allowed the triangulation of complementary evidence between data types, playing to the strengths of each in addressing research questions. For example, detailed etiologic inference from disease-specific cohorts was related to actual population benefit in EHRs. These data were used to generate and test disease progression and health economic models, and to generate research questions intended to inform the design of a new generation of cohorts and clinical trials.

Diverse national databases and registries were available to ROADMAP (Supplementary Table 1). Data from approximately 200 million patients were drawn from several EU Member States (notably Denmark, France, Netherlands, Spain, Sweden, UK) and included 75 national databases and clinical registries, >40 cohorts, several studies of patients using wearables and smart devices, five dementia-relevant trials, and four RCT placebo arms.

ROADMAP used established technologies that facilitate rapid and secure data acquisition, access, and analysis. These technologies were developed further to test the feasibility of using methods primarily developed for broader EHRs for the harmonization of cohort and RCT data. Technologies and methods developed in the IMI EMIF project [11] were used for data source fingerprinting/cataloging and for EHR data extraction and integration across diverse sources and countries. The intention was to map the current landscape of available data across data sources, including EHRs, and to identify data gaps, which should be closed to provide full coverage of relevant outcomes. Cross-cohort analysis was performed using the Dementias Platform UK (DPUK; https://www.dementiasplatform.uk) and the EMIF-AD project integrated informatics environment (https://emif-catalogue.eu). DPUK uses the UK Secure e-Research Platform (UKSeRP) to provide access to dementia-dedicated data, and enables the analysis of cohort data alongside EHRs and other national database records. EMIF-AD uses Jerboa and TranSMART technologies to enable the analysis of EHR data alongside cohort data. The integration of data and analyses was tested by applying unified data extraction and integration technology simultaneously across platforms and remote data locations.

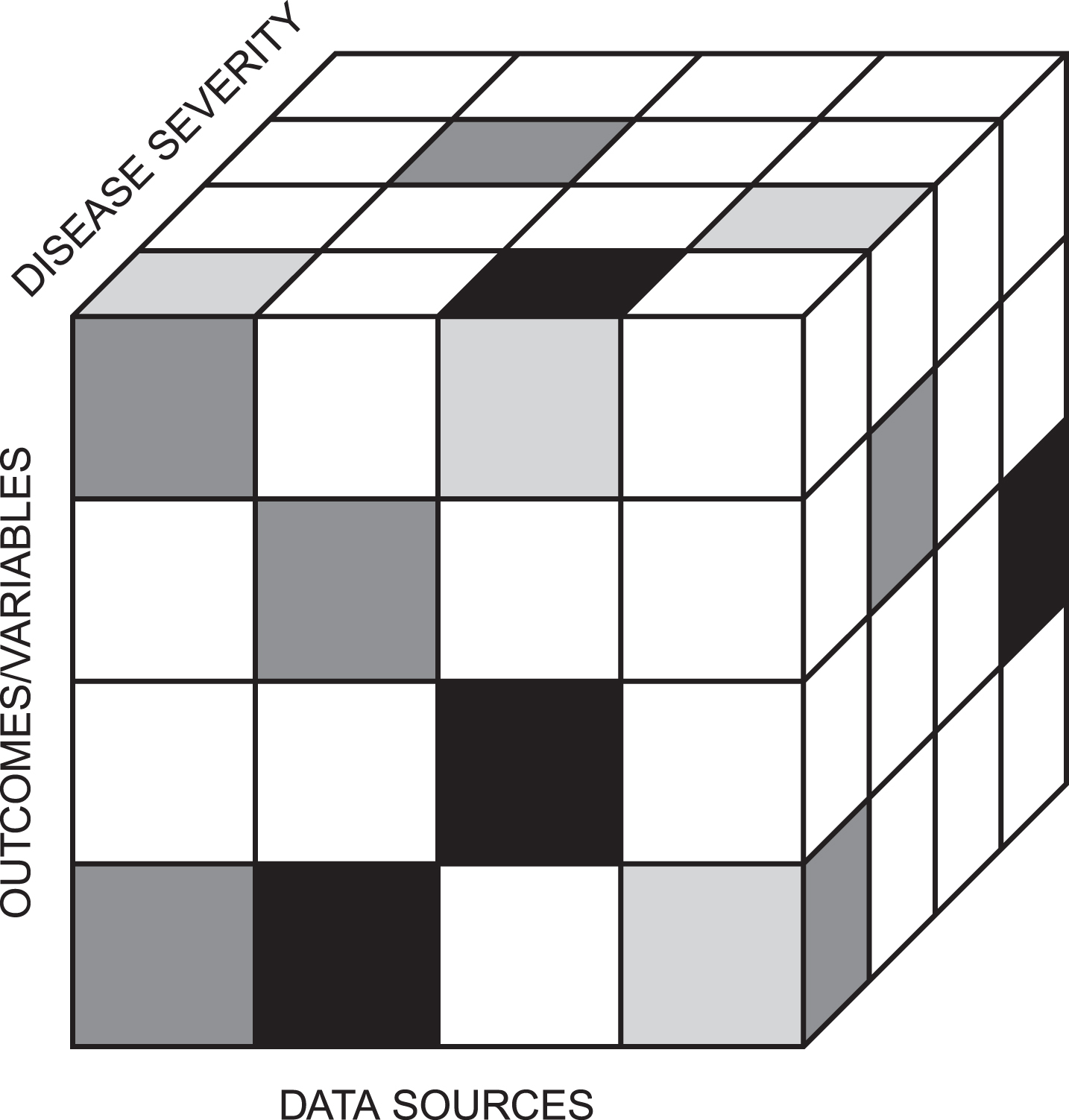

Information was obtained on what constitutes a meaningful delay in disease progression, from clinical (including cognitive, functional, and behavioral changes), humanistic (QoL), and economic perspectives. A ‘data cube’ was used to identify outcomes/variables available from the different data sources and their relation to disease severity (Fig. 1). In addition, ROADMAP identified existing relevant disease models through literature review and contributions from academic and industry partners. These provided an initial framework of reference across the disease spectrum, and were tested and validated using outcomes and datasets also identified during the project.

Fig.1

The ROADMAP data cube: the different data sources covered the whole disease spectrum and contained diverse outcomes/variables.

Specifications for a proof-of-concept cost-effectiveness model to evaluate AD treatments were also developed, and data gaps identified and summarized for future research. These specifications were evaluated considering wider manufacturing, reimbursement, and health policy perspectives as well as best practice within the economic modeling community.

A regulatory and HTA expert advisory group was established, comprising individuals with expertise in regulatory, HTA, and payer requirements across Europe. The objectives of this group were to provide feedback where needed, and to ensure that ROADMAP outputs were of high scientific quality and applicable in a regulatory and HTA context. A separate ethics advisory board, including internal and external experts, was established to provide input on the data integration tools and methodology developed by ROADMAP.

Deliverables and interim results

The ROADMAP key deliverables are summarized in (Table 2). Initial results have already been delivered, including a list of RWE outcomes for AD, an initial set of communication tools, and an overview of potential European RWE data sources (https://roadmap-alzheimer.org/downloads/deliverables/). However, the aim of the present paper is not to report findings; further results and publications will become available in 2019. A strategy was developed [13] for disseminating the results from ROADMAP to the different stakeholders, and also for sharing findings with and from neighboring initiatives, such as EMIF (http://www.emif.eu), AETIONOMY (http://www.aetionomy.eu/), GetReal (http://imi-getreal.eu/), EPAD (http://ep-ad.org/), AMYPAD (http://amypad.eu), and BD4BO (http://bd4bo.eu). This strategy targeted previously disparate audiences, including regulators, payers, HTA bodies, policy-makers, patients, and industry, with the aim of providing an environment in which a broad-based consensus could be established on prioritizing AD-related outcomes, data access and integration protocols, and model development and testing procedures. Key messages were tailored to the interests of the target audiences, and the most appropriate dissemination tools were identified and developed to meet their needs. A second phase of ROADMAP is planned, which will aim to address the identified data gaps from the first phase of the study and continue to engage with stakeholders on methods for optimizing RWE capabilities for activities required to demonstrate the value of new treatments (WP1; Table 1).

Table 2

ROADMAP key deliverablesa

| Defining a minimum set of measurable real-world AD outcomes. |

| This was met in WP2 by developing a matrix of prioritized outcomes according to stakeholder group and, in collaboration with WP3, mapping them against the data available from DPUK cohorts and other relevant European datasets. |

| Developing recommendations on RWE-appropriate, AD-related cognitive, functional, and behavioral outcomes. |

| This was met by work conducted under WP2, WP3, and WP4 using cohorts and other data sources to identify intermediate (and possibly theragnostic) markers that may be transferable to clinical practice. |

| Identifying data sources and outlining a data strategy for RWE outcomes. |

| This was met in WP3 by providing an overview of data sources available throughout Europe (not just within the ROADMAP consortium), the tools available for identifying and combining these data, and opportunities and strategies for pooling data. |

| Developing new methods for collecting RWE to improve how new treatments can be valued in AD. |

| This was met in WP2, WP3, and WP5-8 through engagement with regulators, payers, HTA bodies, patients, caregivers, industry, and researchers. The use of smart devices for self-report, social media, and direct objective assessment applications was of particular interest. |

| Providing recommendations for disease progression modeling. |

| This was met in WP4 using both hypothesis-driven and machine-learning approaches. Both approaches were informed by a review of current models of AD pathology, and by using available datasets for validation of selected models. |

| Developing the concept of an integrated core health economic model of healthcare use/costs and health outcomes in AD. |

| This was met in WP5 in collaboration with WPs 2-4 and 6. It was evidenced on quality of life, resource utilization, and costs associated with AD, and previous AD economic modeling studies, and used systematic reviews to improve the evidence base of long-term AD cost-effectiveness modeling. |

| Identifying guiding principles on the use of RWE in AD in the regulatory/HTA context. |

| Partners in WP6 collected and collated regulatory and HTA-related data to identify possible recommendations for the development and incorporation of RWE into clinical and market-access development plans for AD. |

| Developing requirements for an ethical, legal, and social issues framework for RWE in AD. |

| Partners in WP8 developed a report on ethical, legal, and social issues arising from the combination of datasets from multiple countries for disease, health economic, and treatment modeling for AD, including requirements set out in national ethical and legal frameworks governing local ethics approval. |

aSee Table 1 for Work Packages. AD, Alzheimer’s disease; DPUK, Dementias Platform UK; HTA, health technology assessment; RWE, real-world evidence; WP, Work Package.

THE LIKELY IMPACT OF ROADMAP

The ROADMAP deliverables are congruent with the IMI2 aim of accelerating the development and availability of new therapies (http://www.imi.europa.eu/about-imi/mission-objectives). Networking of multiple healthcare systems should increase competitiveness by delivering knowledge more quickly and cheaply than would otherwise be possible. The output of this collaboration is intended to provide recommendations for: a minimum set of measurable real-world patient outcomes; appropriate AD-related cognitive, functional, and behavioral real-world outcomes; disease progression and health economic modeling; and optimal real-world data collection to improve how new AD treatments can be valued. ROADMAP provided an opportunity to overview the numerous disease progression and economic models developed over the years by many researchers. The immediate impacts from this project will likely be largely instrumental, with patient health benefits observed indirectly through more streamlined decision-making to foster patient access to new therapies. Understanding of the progression of AD across the disease spectrum and measurement of treatment benefits should also be improved.

LIMITATIONS AND CHALLENGES OF ROADMAP

The main challenge of ROADMAP was to identify and access suitable data in the short (2-year) project time frame, which itself was a limitation. Creating a 3-dimensional overview across diverse data sources from multiple countries, and deciding which of the many possible AD-related outcomes were relevant, were particularly challenging. The lack of consensus on which standardized outcomes to use was a limitation that still needs to be overcome. ROADMAP therefore focused on integrating data sources accessible through ROADMAP partners to provide proof that technology solutions could be applied across the various data sources.

CONCLUSIONS

ROADMAP was a collaborative foundation project to identify, test, and evaluate the usability of multiple RWE data sources in the decision-making process for developing new treatments in AD. An unprecedented depth and breadth of RWE data were used to generate and test disease progression and health economic models, and to generate research questions intended to inform the design of a new generation of cohorts and clinical trials. The immediate impacts from the project are likely to be largely instrumental, fostering more streamlined decision-making to improve access to new therapies, and providing a greater understanding of the progression of AD across the disease spectrum.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This project has received funding from the Innovative Medicines Initiative 2 Joint Undertaking under grant agreement No. 116020 (“ROADMAP”). This Joint Undertaking receives support from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program and EFPIA. It is also supported by the Medical Research Council Dementias Platform UK (MR/L023784/1 and MR/009076/1). The authors would like to acknowledge Dr. Sue Chambers and Karen Goa (Rx Communications, Mold, UK) for medical writing assistance with the preparation of this manuscript, funded by Eli Lilly and Company. They would also like to acknowledge the ROADMAP contributors: University of Oxford, UK; National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), UK; Erasmus Universitair Medisch Centrum Rotterdam, the Netherlands; Universiteit Maastricht, the Netherlands; Synapse Research Management Partners SL, Spain; Fundació Institut Universitari per a la Recerca a l’Atenció Primària de Salut Jordi Gol i Gurina, Spain; Københavns Universitet, Denmark; Alzheimer Europe, Luxembourg; University of Edinburgh, UK; Goeteborgs Universitet, Sweden; Aarhus Universitet, Denmark; London School of Economics and Political Science, UK; Agentschap College ter Beoordeling van Geneesmiddelen/Medicines Evaluation Board, the Netherlands; IXICO Technologies Ltd, UK; Rijksuniversiteit Groningen, the Netherlands; Novartis Pharma AG, Switzerland; Eli Lilly and Company Ltd, UK; Biogen Idec Ltd, UK; F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd, Switzerland; Janssen Pharmaceutica NV, Belgium; GE Healthcare Ltd, UK; AC Immune SA, Switzerland; Takeda Development Centre Europe Ltd, UK; H. Lundbeck A/S, Denmark; Leids Universitair Medisch Centrum, the Netherlands; Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Bordeaux, France.

Authors’ disclosures available online (https://www.j-alz.com/manuscript-disclosures/18-0370r1).

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

[1] The supplementary material is available in the electronic version of this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.3233/JAD-180370.

REFERENCES

[1] | Webster L , Groskreutz D , Grinbergs-Saull A , Howard R , O’Brien JT , Mountain G , Banerjee S , Woods B , Perneczky R , Lafortune L , Roberts C , McCleery J , Pickett J , Bunn F , Challis D , Charlesworth G , Featherstone K , Fox C , Goodman C , Jones R , Lamb S , Moniz-Cook E , Schneider J , Shepperd S , Surr C , Thompson-Coon J , Ballard C , Brayne C , Burns A , Clare L , Garrard P , Kehoe P , Passmore P , Holmes C , Maidment I , Robinson L , Livingston G ((2017) ) Core outcome measures for interventions to prevent or slow the progress of dementia for people living with mild to moderate dementia: Systematic review and consensus recommendations. PLoS One 12: , e0179521. |

[2] | Jansen WJ , Ossenkoppele R , Tijms BM , Fagan AM , Hansson O , Klunk WE , van der Flier WM , Villemagne VL , Frisoni GB , Fleisher AS , Lleó A , Mintun MA , Wallin A , Engelborghs S , Na DL , Chételat G , Molinuevo JL , Landau SM , Mattsson N , Kornhuber J , Sabri O , Rowe CC , Parnetti L , Popp J , Fladby T , Jagust WJ , Aalten P , Lee DY , Vandenberghe R , Resende de Oliveira C , Kapaki E , Froelich L , Ivanoiu A , Gabryelewicz T , Verbeek MM , Sanchez-Juan P , Hildebrandt H , Camus V , Zboch M , Brooks DJ , Drzezga A , Rinne JO , Newberg A , de Mendonca A , Sarazin M , Rabinovici GD , Madsen K , Kramberger MG , Nordberg A , Mok V , Mroczko B , Wolk DA , Meyer PT , Tsolaki M , Scheltens P , Verhey FRJ , Visser PJ , Amyloid Biomarker Study Group ((2018) ) Association of cerebral amyloid-β aggregation with cognitive functioning in persons without dementia. JAMA Psychiatry 75: , 84–95. |

[3] | Buchhave P , Minthon L , Zetterberg H , Wallin AK , Blennow K , Hansson O ((2012) ) Cerebrospinal fluid levels of β-amyloid 1-42, but not of tau, are fully changed already 5 to 10 years before the onset of Alzheimer dementia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 69: , 98–106. |

[4] | Molinuevo JL , Cami J , Carné X , Carrillo MC , Georges J , Isaac MB , Khachaturian Z , Kim SY , Morris JC , Pasquier F , Ritchie C , Sperling R , Karlawish J ((2016) ) Ethical challenges in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease observational studies and trials: Results of the Barcelona summit. Alzheimers Dement 12: , 614–622. |

[5] | Vellas B , Carrillo MC , Sampaio C , Brashear HR , Siemers E , Hampel H , Schneider LS , Weiner M , Doody R , Khachaturian Z , Cedarbaum J , Grundman M , Broich K , Giacobini E , Dubois B , Sperling R , Wilcock GK , Fox N , Scheltens P , Touchon J , Hendrix S , Andrieu S , Aisen P , EU/US/CTAD Task Force Members ((2013) ) Designing drug trials for Alzheimer’s disease: What we have learned from the release of the phase III antibody trials: A report from the EU/US/CTAD Task Force. Alzheimers Dement 9: , 438–444. |

[6] | Bature F , Guinn BA , Pang D , Pappas Y ((2017) ) Signs and symptoms preceding the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: A systematic scoping review of literature from 1937 to 2016. BMJ Open 7: , e015746. |

[7] | Dong A , Toledo JB , Honnorat N , Doshi J , Varol E , Sotiras A , Wolk D , Trojanowski JQ , Davatzikos C , Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative ((2017) ) Heterogeneity of neuroanatomical patterns in prodromal Alzheimer’s disease: Links to cognition, progression and biomarkers. Brain 140: , 735–747. |

[8] | Schlegl E , Ducournau P , Ruof J ((2017) ) Different weights of the evidence-based medicine triad in regulatory, health technology assessment, and clinical decision making. Pharmaceut Med 31: , 213–216. |

[9] | Schneeweiss S , Eichler HG , Garcia-Altes A , Chinn C , Eggimann AV , Garner S , Goettsch W , Lim R , Löbker W , Martin D , Müller T , Park BJ , Platt R , Priddy S , Ruhl M , Spooner A , Vannieuwenhuyse B , Willke RJ ((2016) ) Real world data in adaptive biomedical innovation: A framework for generating evidence fit for decision-making. Clin Pharmacol Ther 100: , 633–646. |

[10] | Sherman RE , Anderson SA , Dal Pan GJ , Gray GW , Gross T , Hunter NL , LaVange L , Marinac-Dabic D , Marks PW , Robb MA , Shuren J , Temple R , Woodcock J , Yue LQ , Califf RM ((2016) ) Real-world evidence – what is it and what can it tell us? N Engl J Med 375: , 2293–2297. |

[11] | Perera G , Pedersen L , Ansel D , Alexander M , Arrighi HM , Avillach P , Foskett N , Gini R , Gordon MF , Gungabissoon U , Mayer MA , Novak G , Rijnbeek P , Trifirò G , van der Lei J , Visser PJ , Stewart R ((2018) ) Dementia prevalence and incidence in a federation of European Electronic Health Record databases: The European Medical Informatics Framework resource. Alzheimers Dement 14: , 130–139. |

[12] | Ritchie CW , Molinuevo JL , Truyen L , Satlin A , Van der Geyten S , Lovestone S , European Prevention of Alzheimer’s Dementia (EPAD) Consortium ((2016) ) Development of interventions for the secondary prevention of Alzheimer’s dementia: The European Prevention of Alzheimer’s Dementia (EPAD) project. Lancet Psychiatry 3: , 179–186. |

[13] | ROADMAP (2017) D7.4 Interim report on dissemination activities and communication strategy update, https://roadmap-alzheimer.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/116020_ROADMAP_D7.4-Interim-Report-on-disination-activities-and-communication-strategy-update-V1.4.pdf, Last updated November 8, 2017, Accessed February 20, 2018. |