Abstract

Background: The role of antidepressants in the management of fibromyalgia syndrome (FMS) still needs to be determined.

Objective: The objective of this study was to provide a quantitative analysis (meta-analysis) of the efficacy and harms of antidepressants in the management of adult FMS patients.

Data sources: The data sources used were the databases MEDLINE, SCOPUS and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (until December 30, 2010), the reference lists of included articles, and the websites of the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (PhRMA).

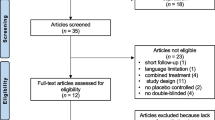

Study selection: Studies with a randomized controlled trial (RCT) design comparing any types of antidepressants with pharmacological placebo or head-to-head comparisons of different types of antidepressants in FMS patients were included. RCTs in which antidepressants were combined with any other defined treatment or antidepressants were tested against anything but drug placebo were excluded. Patients diagnosed with FMS according to predefined criteria of any age were included. To be included, studies had to assess at least one key domain of FMS (pain, sleep, fatigue, health-related quality of life [HRQOL]) as outcomes of efficacy and report total treatment discontinuation rates and/or dropout rates due to adverse events as outcomes for harms.

Data extraction: Data were extracted according to protocols of previous systematic reviews on antidepressants in FMS. Methodology quality was assessed by the van Tulder score.

Data synthesis: Standardized mean differences (SMD) were calculated for continuous outcomes by means and standard deviations and relative risks (RR) for 30% pain reduction and total dropout rate for comparisons of antidepressants with placebo. Examination of the combined results was performed by a random effects model. We used Cohen’s categories to evaluate the magnitude of the effect size, calculated by SMD. Heterogeneity was tested by the I2 statistic.

Thirty-five studies were included in the meta-analysis. The SMDs of serotonin noradrenaline (norepinephrine) reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) on pain, sleep, fatigue, depression and HRQOL were significant. Based on Cohen’s categories, the effect size on pain was small and the ones on sleep, fatigue, depression and HRQOL were not substantial. 1481/3528 (42.0%) patients with SNRIs and 737/2304 (32.0%) patients with placebo reported a 30% pain reduction (number needed to treat [NNT] 10.0; 95% CI 8.00,13.4; I2=4%). The RR of dropouts due to adverse events was 1.83 (95% CI 1.53, 2.18; I2 = 33%).

The SMDs of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) on pain, sleep, depression and HRQOL were significant. Based on Cohen’s categories, the effect sizes on pain, depression and HRQOL were small and the one on sleep not substantial. 72/198 (36.4%) patients with SSRIs and 40/194 (20.6%) patients with placebo reported a 30% pain reduction (NNT 6.3; 95% CI 4.1,14.1). The RR of dropouts due to adverse events was 1.60 (95% CI 0.84, 3.04; I2=0%).

The SMDs of tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) on pain, sleep, fatigue and HRQOL were significant. Based on Cohen’s categories, the effect sizes on pain and sleep were moderate and the ones on fatigue and HRQOL were small. 140/290 (48.3%) patients with TCAs and 70/252 (27.8%) patients with placebo reported a 30% pain reduction (NNT 4.9; 95% CI 3.5, 8.0). The RR of dropouts due to adverse events was 0.84 (95% CI 0.46, 1.52; I2 = 0%).

Conclusions: The TCA amitriptyline and the SNRIs duloxetine and milnacipran are first-line options for the treatment of FMS patients. Physicians and patients should be realistic about the potential benefits of antidepressants in FMS. A small number of patients experience a substantial symptom relief with no or minor adverse effects. However, a remarkable number of patients dropout of therapy because of intolerable adverse effects or experience only a small relief of symptoms, which does not outweigh the adverse effects.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Häuser W, Zimmer C, Felde E, et al. What are the key symptoms of fibromyalgia syndrome? Results of a survey of the German Fibromyalgia Association [in German]. Schmerz 2008; 22: 176–83

Wolfe F, Clauw DJ, Fitzcharles MA, et al. The American College of Rheumatology preliminary diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia and measurement of symptom severity. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2010; 62: 600–10

Wolfe F, Anderson J, Harkness D, et al. A prospective, longitudinal, multicenter study of service utilization and costs in fibromyalgia. Arthritis Rheum 1997; 40: 1553–5

Winkelmann A, Perrot S, Schaefer C, et al. Impact of fibromyalgia severity on health economic costs: results from a European cross-sectional study. Appl Health Econ Health Policy 2011; 9: 125–36

Henningsen P, Zipfel S, Herzog W. Management of functional somatic syndromes. Lancet 2007 Mar 17; 369: 946–55

Fietta P, Fietta P, Manganelli P. Fibromyalgia and psychiatric disorders. Acta Biomed 2007; 78: 88–95

Weir PT, Harlan GA, Nkoy FL, et al. The incidence of fibromyalgia and its associated comorbidities: a populationbased retrospective cohort study based on International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision codes. J Clin Rheumatol 2006; 12: 124–8

Lawrence RC, Felson DT, Helmick CG, et al. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the United States: part II. Arthritis Rheum 2008; 58: 26–35

Wolfe F, Smythe HA, Yunus MB, et al. The American College of Rheumatology 1990 criteria for the classification of fibromyalgia: report of the Multicenter Criteria Committee. Arthritis Rheum 1990; 33: 1863–4

Branco JC, Bannwarth B, Failde I, et al. Prevalence of fibromyalgia: a survey in five European countries. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2010; 39: 448–55

Sommer C, Häuser W, Gerhold K, et al. Etiology and pathophysiology of fibromyalgia syndrome and chronic widespread pain [in German]. Schmerz 2008; 22(3): 267–82

Bradley LA. Pathophysiology of fibromyalgia. Am J Med 2009; 122(12 Suppl. ): S22–30

Wolfe F. Fibromyalgia wars. J Rheumatol 2009; 36(4): 671–8

Bennett RM, Jones J, Turk DC, et al. An internet survey of 2,596 people with fibromyalgia. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2007 Mar 9; 8: 27

Marschall U, Arnold B, Häuser W. Treatment and healthcare costs of fibromyalgia syndrome in Germany: analysis of the data of the Barmer Health Insurance (BEK) from 2008–2009 [in German]. Schmerz 2011; 25: 402–10

Burckhardt CS, Goldenberg D, Crofford L, et al. Guideline for the management of fibromyalgia syndrome: pain in adults and children. APS Clinical Practice Guideline Series No. 4. Glenview (IL): American Pain Society, 2005

Carville SF, Arendt-Nielsen S, Bliddal H, et al. EULAR evidence based recommendations for the management of fibromyalgia syndrome. Ann Rheum Dis 2008; 67: 536–41

Häuser W, Eich W, Herrmann M, et al. Fibromyalgia syndrome: classification, diagnosis, and treatment. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2009; 106: 383–91

Häuser W, Thieme K, Turk DC. Guidelines on the management of fibromyalgia syndrome: a systematic review. Eur J Pain 2010; 14: 5–10

Briley M. Drugs to treat fibromyalgia: the transatlantic difference. Curr Opin Inves Drugs 2010; 11: 16–8

Häuser W, Petzke F, Üçeyler N, et al. Comparative efficacy and acceptability of amitriptyline, duloxetine and milnacipran in fibromyalgia syndrome: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2011; 50: 532–43

Verdu B, Decosterd I, Buclin T, et al. Antidepressants for the treatment of chronic pain. Drugs 2008; 68: 2611–32

Chan HN, Fam J, Ng BY. Use of antidepressants in the treatment of chronic pain. Ann Acad Med Singapore 2009; 38: 974–9

Mease PJ, Clauw DJ, Christensen R, et al., OMERACT Fibromyalgia Working Group. Toward development of a fibromyalgia responder index and disease activity score: OMERACT module update. J Rheumatol 2011; 38: 1487–95

Cipriani A, Furukawa TA, Salanti G, et al. Comparative efficacy and acceptability of 12 new-generation antidepressants: a multiple-treatments meta-analysis. Lancet 2009; 373: 746–58

Häuser W, Bernardy K, Uçeyler N, et al. Treatment of fibromyalgia syndrome with antidepressants: a metaanalysis. JAMA 2009; 301: 198–209

Furukawa TA, Cipriani A, Barbui C, et al. Imputing response rates from means and standard deviations in metaanalyses. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 2005; 20: 49–52

van Tulder M, Furlan A, Bombardier C, et al. Updated method guidelines for systematic reviews in the cochrane collaboration back review group. Spine 2003; 28: 1290–9

Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Hillsdale (NJ): Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1988

Higgins JPT, Green S, editors. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions, version 5.1.0, updated March 2011 [online]. Available from URL: http://www.cochrane-handbook.org/ [Accessed 2011 Dec 6]

Rief W, Nestoriuc Y, Weiss S, et al. Meta-analysis of the placebo response in antidepressant trials. J Affect Disord 2009; 118: 1–8

Kelly J. Pfizer stops work on esreboxetine for FM [online]. Available from URL: http://www.mskreport.com/articles.cfm?articleID=3293 [Accessed 2011 Feb 23]

Häuser W, Bartram C, Bartram-Wunn E, et al. Systematic review: adverse events attributable to nocebo in randomised controlled drug trials in fibromyalgia syndrome and painful diabetic peripheral neuropathy. Clin J Pain. Epub 2012 Feb 14

Amanzio M, Corazzini LL, Vase L, et al. A systematic review of adverse events in placebo groups of anti-migraine clinical trials. Pain 2009; 146: 261–9

Drugs information online. Duloxetine [online]. Available from URL: http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2010/022516lbl.pdf [Accessed 2011 Aug 15]

Drugs information online. Milnacipran [online]. Available from URL: http://www.drugs.com/pro/savella.html [Accessed 2011 Aug 15]

Drugs information online. Fluoxetine [online]. Available from URL: http://www.drugs.com/pro/fluoxetine.html [Accessed 2011 Aug 15]

Drugs information online. Paroxetine [online]. Available from URL: http://www.drugs.com/pro/paxil.html [Accessed 2011 Aug 15]

Drugs information online. Amitriptyline [online]. Available from URL: http://www.drugs.com/pro/amitriptyline.html [Accessed 2011 Aug 15]

Häuser W, Bartram-Wunn E, Bartram C, et al. Systematic review: placebo response in drug trials of fibromyalgia syndrome and painful peripheral diabetic neuropathy: magnitude and patient-related predictors. Pain 2011; 152: 1709–17

Ernst E, Herxheimer A. The power of placebo. BMJ 1996; 313: 1569–70

Walitt B, Fitzcharles MA, Hassett AL, et al. The longitudinal outcome of fibromyalgia: a study of 1555 patients. J Rheumatol 2011; 38: 2238–46

Arnold LM, Rosen A, Pritchett YL, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of duloxetine in the treatment of women with fibromyalgia with or with out major depressive disorder. Pain 2005; 119: 5–15

Russell IJ, Mease PJ, Smith TR, et al. Efficacy and safety of duloxetine for treatment of fibromyalgia in patients with or without major depressive disorder: results from a 6-month, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, fixed-dose trial. Pain 2008; 136: 432–44

Mainguy Y. Functional magnetic resonance imagery (fMRI) in fibromyalgia and the response to milnacipran. Hum Psychopharmacol 2009; 24 Suppl. 1: S19–23

Arnold LM, Clauw DJ. Fibromyalgia syndrome: practical strategies for improving diagnosis and patient outcomes. Am J Med 2010; 123: S2

Häuser W, Klose P, Langhorst J, et al. Efficacy of different types of aerobic exercise in fibromyalgia syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Arthritis Res Ther 2010; 12: R79

Langhorst J, Musial F, Klose P, et al. Efficacy of hydrotherapy in fibromyalgia syndrome: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled clinical trials. Rheumatol (Oxford) 2009; 48: 1155–9

Häuser W, Bernardy K, Offenbächer M, et al. Efficacy of multicomponent treatment of fibromyalgia syndrome: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Arthritis Rheum 2009; 61: 216–24

Acknowledgements

Dr Häuser received honoraria for one educational lecture from Janssen-Cilag. The National Data Bank for Rheumatic Diseases, the employer of Dr Frederick Wolfe, received a grant from Pfizer for conducting a fibromyalgia criteria study. Dr Tölle received grants within the innovative medicines initiative supported by Pfizer and payments for lectures including services on speakers’ bureaus from Pfizer, Eli-Lilly, Grünenthal and Astellas. Dr Üçeyler has no conflicts of interest to declare. Dr Sommer received honoraria for educational lectures from Pfizer and Eli-Lilly and has participated in advisory boards of these companies.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Häuser, W., Wolfe, F., Tölle, T. et al. The Role of Antidepressants in the Management of Fibromyalgia Syndrome. CNS Drugs 26, 297–307 (2012). https://doi.org/10.2165/11598970-000000000-00000

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.2165/11598970-000000000-00000