Abstract

Background and Objective: The ability to value health in a way that allows the comparison of different conditions across a range of population groups is central to determining priorities in healthcare. This paper considers some of the concerns with the ‘received wisdom’ in valuing health — to describe it using a generic descriptive system and to value it using the hypothetical preferences of the general public.

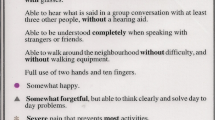

Methods: The literature on the dimensions of health that matter most to people was reviewed and this paper discusses the use of global measures of subjective well-being (SWB) as a possible alternative. New analysis of the British Household Panel Survey was conducted to explore the relationship between life satisfaction and the preference-based quality-of-life measure the SF-6D. The impact on life satisfaction of each level for each dimension of the SF-6D is estimated through a linear model predicting life satisfaction with the SF-6D levels as determinants.

Results: Valuing changes in the health of the general population via changes in life satisfaction would lead to different weights being attached to the different dimensions of health, as compared to a well used utility score in which weights are taken from general population preferences. If preferences elicited via standard gamble exercises are based only on a prediction of what it would be like to live in a particular health state, then these results suggest that reductions in physical functioning matter less than people imagine and reductions in mental health impact upon our lives more than preferences would suggest.

Conclusions: Using data from the British Household Panel Survey, it is shown that a focus on SWB would place greater emphasis on mental health conditions. The implications for health policy are considered.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

HM Government. The Coalition: our programme for government. London: Cabinet Office, 2010 [online]. Available from URL: http://www.cabinetoffice.gov.uk/sites/default/files/resources/coalition_programme_for_government.pdf [Accessed 2012 Jul 18].

Department of Health. Equity and excellence: liberating the NHS. London: The Stationery Office, 2010 [online]. Available from URL: http://www.dh.gov.uk/prod_consum_dh/groups/dh_digitalassets/@dh/@en/@ps/documents/digitalasset/dh_117794.pdf [Accessed 2012 Jul 18].

Bentham J. An introduction to the principles of morals and legislations. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1789.

Dolan P. Modeling valuations for EuroQol health states. Med Care 1997 Nov; 35 (11): 1095–108.

Brazier J, Roberts J, Deverill M. The estimation of a preference-based measure of health from the SF-36. J Health Econ 2002 Mar; 21 (2): 271–92.

Carr AJ, Higginson IJ. Are quality of life measures patient centred? BMJ 2001 Jun 2; 322 (7298): 1357–60.

Gill TM, Feinstein AR. A critical appraisal of the quality of quality-of-life measurements. JAMA 1994 Aug 24–31; 272 (8): 619–26.

Bowling A. What things are important in people’s lives? A survey of the public’s judgements to inform scales of health related quality of life. Soc Sci Med 1995 Nov; 41 (10): 1447–62.

Hickey AM, Bury G, O’Boyle CA, et al. A new short form individual quality of life measure (SEIQoL-DW): application in a cohort of individuals with HIV/AIDS. BMJ 1996 Jul 6; 313 (7048): 29–33.

Levack P, Graham J, Kidd J. Listen to the patient: quality of life of patients with recently diagnosed malignant cord compression in relation to their disability. Palliat Med 2004 Oct; 18 (7): 594–601.

Singer PA, Martin DK, Kelner M. Quality end-of-life care: patients’ perspectives. JAMA 1999 Jan 13; 281 (2): 163–8.

Heyland DK, Dodek P, Rocker G, et al. What matters most in end-of-life care: perceptions of seriously ill patients and their family members. CMAJ 2006 Feb 28; 174 (5): 627–33.

Steinhauser KE, Christakis NA, Clipp EC, et al. Factors considered important at the end of life by patients, family, physicians, and other care providers. JAMA 2000 Nov 15; 284 (19): 2476–82.

Singer PA, Martin DK, Lavery JV, et al. Reconceptualizing advance care planning from the patient’s perspective. Arch Intern Med 1998 Apr 27; 158 (8): 879–84.

Schaffer A, Levitt AJ, Hershkop SK, et al. Utility scores of symptom profiles in major depression. Psychiatry Res 2002 Jun 1; 110 (2): 189–97.

Ubel PA, Richardson J, Baron J. Exploring the role of order effects in person trade-off elicitations. Health Policy 2002 Aug; 61 (2): 189–99.

Konig HH, Gunther OH, Angermeyer MC, et al. Utility assessment in patients with mental disorders: validity and discriminative ability of the time trade-off method. Pharmacoeconomics 2009; 27 (5): 405–19.

Dolan P, Kahneman D. Interpretations of utility and their implications for the valuation of health. Econ J 2008 Jan; 118 (525): 215–34.

Stiglitz J, Sen A, Fitoussi JP. Report by the Commission on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress. Paris: Commission on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress, 2009.

Layard R. Happiness: lessons from a new science. London: Penguin, 2005.

Helliwell J. Wellbeing, social capital and public policy: what’s new? Econ J 2006; 116 (510): C34–45.

BBC News. Cameron speech on happiness survey. 2010 Nov 25 [online]. Available from URL: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-politics-11837785 [Accessed 2010 Dec 8].

Graham C. Happiness and health: lessons-and questions-for public policy. Health Aff (Millwood) 2008 Jan–Feb; 27 (1): 72–87.

Glenn ND, Weaver CN. The changing relationship of marital status to reported happiness. J Marriage Family 1985; 50: 315–24.

Stutzer A, Frey BS. Does marriage make people happy, or do happy people get married? J Socio-Economics 2003; 35 (2): 326–47.

Di Tella R, MacCulloch R, Oswald A. Preferences over inflation and unemployment: evidence from surveys of happiness. Am Econ Rev 2001; 91 (1): 335–41.

Winkleman L, Winkleman R. Why are the unemployed so unhappy? Econometrica 1998; 65 (257): 1–15.

Helliwell J, Putman R. The social context of wellbeing. Phil Trans R Soc Lon 2004; 359: 1435–46.

Dolan P, Peasgood T, White M. Do we really know what makes us happy? A review of the economic literature on the factors associated with subjective well-being. J Econ Psychol 2008; 29: 94–122.

Marmot M. The social gradient in health and well-being [abstract]. Brookings Warwick Conference. Why inequality matters: lessons for policy from the economics of happiness; 2003 Jun 5–6; Washington, DC.

Verbrugge LM, Reoma JM, Gruber-Baldini AL. Short-term dynamics of disability and well-being. J Health Soc Behav 1994 Jun; 35 (2): 97–117.

Diener E, Seligman ME. Very happy people. Psychol Sci 2002 Jan; 13 (1): 81–4.

Koivumaa-Honkanen HT, Honkanen R, Antikainen R, et al. Self-reported life satisfaction and treatment factors in patients with schizophrenia, major depression and anxiety disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1999 May; 99 (5): 377–84.

Packer S, Husted J, Cohen S, et al. Psychopathology and quality of life in schizophrenia. J Psychiatry Neurosci 1997 Jul; 22 (4): 231–4.

Sackett DL, Torrance GW. The utility of different health states as perceived by the general public. J Chronic Dis 1978; 31 (11): 697–704.

Hurst NP, Jobanputra P, Hunter M, et al. Validity of Euroqol-a generic health status instrument-in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Economic and Health Outcomes Research Group. Br J Rheumatol 1994 Jul; 33 (7): 655–62.

Ubel PA, Loewenstein G, Jepson C. Whose quality of life? A commentary exploring discrepancies between health state evaluations of patients and the general public. Qual Life Res 2003 Sep; 12 (6): 599–607.

Pyne JM, Fortney JC, Tripathi S, et al. How bad is depression? Preference score estimates from depressed patients and the general population. Health Serv Res 2009 Aug; 44 (4): 1406–23.

Graham C, Higuera L, Lora E. Valuing health conditions: insights from happiness surveys across countries and cultures [IDB working papers series]. Washington, DC: Inter-American Development Bank, Department of Research and Chief Economist, 2009 [online]. Available from URL: http://www.iadb.org/res/publications/pubfiles/pubIDB-WP-100.pdf [Accessed 2012 Jun 18].

Oswald AJ, Powdthavee N. Does happiness adapt? A longitudinal study of disability with implications for economists and judges. J Public Econ 2008; 92: 1061–77.

Shields M, Wheatley Price S. Exploring the economic and social determinants of psychological wellbeing and perceived social support in England. J Royal Stat Soc 2005; 168 (3): 513–37.

Blanchflower DG, Oswald AJ. Hypertension and happiness across nations. J Health Econ 2008 Mar; 27 (2): 218–33.

Brazier JE, Rowen D, Hanmer J. Revised SF-6D scoring programmes: a summary of improvements. Patient Reported Outcomes Newsletter 2008; 40: 14–5.

Ferrer-i-Carbonell A, Frijters P. How important is methodology for the estimates of the determinants of happiness? Econ J 2004; 114: 641–59.

BHPS. British Household Panel Survey. 2011 [online]. Available from URL: http://www.iser.essex.ac.uk/survey/bhps [Accessed 2011 Feb 1].

Office for National Statistics. Measuring national well-being: consultation. London: Office for National Statistics, 2010.

Hayman JA, Kabeto MU, Schipper MJ, et al. Assessing the benefit of radiation therapy after breast-conserving surgery for ductal carcinoma-in-situ. J Clin Oncol 2005 Aug 1; 23 (22): 5171–7.

Peasgood T, Ward SE, Brazier J. Health-state utility values in breast cancer. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res 2010 Oct; 10 (5): 553–66.

Sprangers MA, Schwartz CE. Integrating response shift into health-related quality of life research: a theoretical model. Soc Sci Med 1999 Jun; 48 (11): 1507–15.

Richardson J, Richardson J. Chapter 3.7: evaluating summary measures of population health. In: Murray CJL, Saloman JA, Mathers CD, et al., editors. Summary measures of population health: concepts, ethics, measurement and applications. Geneva: WHO, 2002: 147–59.

Mukuria C, Brazier J. Exploring the relationship between two health state classification systems and happiness using a large patient data set [HEDS discussion paper 11/07]. Sheffield: University of Sheffield, 2011 [online]. Available from URL: http://www.shef.ac.uk/polopoly_fs/1.54743!/file/HEDS_DP_11-07.pdf [Accessed 2012 Sep 5].

Albrecht GL, Devlieger PJ. The disability paradox: high quality of life against all odds. Soc Sci Med 1999 Apr; 48 (8): 977–88.

Allison PJ, Locker D, Feine JS. Quality of life: a dynamic construct. Soc Sci Med 1997 Jul; 45 (2): 221–30.

Breetvelt IS, Van Dam FS. Underreporting by cancer patients: the case of response-shift. Soc Sci Med 1991; 32 (9): 981–7.

Carver CS, Scheier MF. Scaling back goals and recalibration of the affect system are processes in normal adaptive self-regulation: understanding ‘response shift’ phenomena. Soc Sci Med 2000 Jun; 50 (12): 1715–22.

Sen AK. Commodities and capabilities. Oxford: Elsevier Science Publishers, 1985

Qizilbash M. Well-being, adaptation and human limitations. Royal Institute of Philosophy Supplements 2006; 88: 83–110.

Menzel P, Dolan P, Richardson J, et al. The role of adaptation to disability and disease in health state valuation: a preliminary normative analysis. Soc Sci Med 2002 Dec; 55 (12): 2149–58.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Pfizer for supporting this work (the authors’ work is independent of the funders, who have reviewed the manuscript) and the UK Data Archive for supplying the data from the BHPS. Neither the original collectors of the data nor the archive bear any responsibility for the analysis or interpretations presented here.

The authors would also like to thank Robert Metcalfe for help with this and other related work, and also Julie Ann Bridge and Warren Cowell for their helpful comments on the manuscript. They are extremely grateful to the thoughtful and helpful comments of two referees.

There are no conflicts of interest.

PD and TP conceived the original idea for the research. TP performed the analysis of the BHPS dataset. HL conducted the background literature review and prepared the draft manuscript. PD revised the manuscript and analyses. All authors have reviewed and made significant contributions to the final manuscript. PD acts as guarantor for the overall content.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Dolan, P., Lee, H. & Peasgood, T. Losing Sight of the Wood for the Trees. PharmacoEconomics 30, 1035–1049 (2012). https://doi.org/10.2165/11593040-000000000-00000

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.2165/11593040-000000000-00000