Abstract

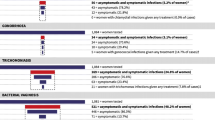

Testing for and treating sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) in pregnant women deserves special attention. Treatment possibilities are limited because of potential risks for the developing fetus, and because effects can differ in pregnant compared with non-pregnant women, re-infection may be missed because of the intrinsic delicacy of contact-tracing during pregnancy and because pregnant women are more reluctant to take the prescribed medication in its full dose, if at all. However, the devastating effects of some of these genital infections far outweigh any potential adverse effects of treatment.

Although active syphilis has become a rarity in most Western countries, it is still prevalent in South America, Africa and South-East Asia. Benzathine benzylpenicillin (2.4 million units once or, safer, twice 7 days apart) is the treatment of choice, although patients with syphilis of longer standing require 3 weekly injections as well as extensive investigation into whether there has been any damage due to tertiary syphilis. Despite declining rates of gonorrhea, the relative rate of penicillinase-producing strains is increasing, especially in South-East Asia. The recommended treatment is intramuscular ceftriaxone (125 or 250mg) or oral cefixime 400mg. Despite good safety records after accidental use, fluoroquinolones are contraindicated during pregnancy. An alternative to a fluoroquinolone in pregnant women with combined gonorrhea and chlamydial infection is oral azithromycin 1 or 2g. Azithromycin as a single 1g dose is also preferable to a 7 day course of erythromycin 500mg 4 times a day for patients with chlamydial infection. Eradication of Haemophilus ducreyi in patients with chancroid can also be achieved with these regimens or intramuscular ceftriaxone 250mg. Trichomonas vaginalis, which is often seen as a co-infection, has been linked to an increased risk of preterm birth. Patients infected with this parasite should therefore received metronidazole 500mg twice daily for 7 days as earlier fears of teratogenesis in humans have not been confirmed by recent data.

Bacterial vaginosis is also associated with preterm delivery in certain risk groups, such as women with a history of preterm birth or of low maternal weight. Such an association is yet to be convincingly proven in other women. The current advice is to treat only women diagnosed with bacterial vaginosis who also present other risk factors for preterm delivery. The treatment of choice is oral metronidazole 1 g/day for 5 days. The possible reduction of preterm birth by vaginally applied metronidazole or clindamycin is still under investigation.

In general, both test of cure and re-testing after several weeks are advisable in most pregnant patients with STDs, because partner notification and treatment are likely to be less efficient than outside pregnancy and the impact of inadequately treated or recurrent disease is greater because of the added risk to the fetus. Every diagnosis of an STD warrants a full screen for concomitant genital disease. Most ulcerative genital infections, as well as abnormal vaginal flora and bacterial vaginosis, increase the sexual transmission efficiency of HIV, necessitating even more stringent screening for and treating of STD during pregnancy.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Donders GGG, Desmyter J, De Wet GH, et al. The association of gonorrhoea and syphilis with premature birth and low birth weight. Genitourin Med 1993; 69: 98–101

Donders GGG, Desmyter J, Hooft P, et al. Apparent failure of one injection of benzathine penicillin G for syphilis during pregnancy in human immunodeficiency virus-negative African women. Sex Transm Dis 1997; 24: 96–101

Stray-Pedersen B. Cost-benefit analysis of a prenatal preventive programme against congenital syphilis. NIPH Ann 1980; 48: 57–66

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Guidelines and treatment of sexually transmitted diseases: MMWR recommendations and report. Atlanta (GA): US Department of Health and Human Services, 1998

Alexander JM, Sheffield JS, Sanchez PJ, et al. Efficacy of treatment for syphilis in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 1999; 93: 5–8

Conover CS, Rend CA, Miler Jr GB, et al. Congenital syphilis after treatment of maternal syphilis with a penicillin regimen exceeding CDC guidelines. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol 1998; 6: 134–7

McFarlin BL, Bottoms SF, Dock BS, et al. Epidemic syphilis: maternal factors associated with congenital infection. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1994; 70: 535–40

Wendel Jr GD, Sark BJ, Jamison RB, et al. Penicillin allergy and desensitization in serious infections in pregnancy. N Engl J Med 1985; 312: 1229–32

Hook EW, Roddy RE, Handsfield HH. Ceftriaxone for incubating and early syphilis. J Infect Dis 1988; 158: 881–4

Moorthy TT, Lee C-T, Lin K-B, et al. Ceftriaxone for treatment of primary syphilis in men: a preliminary study. Sex Transm Dis 1987; 14: 116–8

Lind I, Arborio M, Bentzon MW, et al. The epidemiology of Neisseria gonorrhoeae isolates in Dakar, Sénégal 1982–1986: antimicrobial resistance, auxotypes and plasmid profiles. Genitourin Med 1991; 67: 107–13

Kohl PK, Tu Y, Hostalek U, et al. Activity of cefixime against Neisseria gonorrhoeae. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venerol 1995; 4: 155–9

Mandell GL, Douglas Jr RG, Bennett JE, et al. Treatment of sexually transmitted diseases. In: Mandell GL, Douglas RG, Bennett JE, editors. Principles and practice of infectious diseases: antimicrobial therapy 1996/ 1997. New York (NY): Churchill Livingstone, 1996: 92–6

Judson FN. Treatment of uncomplicated gonorrhea with ceftriaxone: a review. Sex Transm Dis 1986; 13: 199–202

Ueland K, Metcalfe J. Circulatory changes in pregnancy. Clin Obstet Gynecol 1975; 18: 41–56

Zishka PA, Douglas JM. Immediate hypersensitivity reaction to single-dose parenteral ceftriaxone therapy for gonorrhea. Sex Transm Dis 1992; 18: 26–7

Ingham B, Brentnall DW, Dale EA, et al. Arthropathy induced by antibacterial fused N-alkyl-4-pyridone-3-carboxylic acids. Toxicol Lett 1977; 6: 21–6

Schaefer C, Amoura-Elefant E, Vial T, et al. Pregnancy outcome after prenatal quinolone exposure: evaluation of a case registry of the European Network of Teratology Information Services 5 (ENTIS). Eur J Obstet Gynecol Obstet Reprod Biol 1996; 69: 83–9

Loebstein R, Addis A, Ho E, et al. Pregnancy outcome following gestational exposure to fluoroquinolones: a multicenter prospective controlled study. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1998; 42: 1336–9

Handsfield HH, McCormack WM, Hook III EW, et al. A comparison of single dose cefixime with ceftriaxone as treatment for uncomplicated gonorrhea. N Engl J Med 1991; 325: 1337–41

Verdon MS, Douglas JM, Wiggins SD, et al. Treatment of uncomplicated gonorrhea with single doses of 200 mg cefixime. Sex Transm Dis 1993; 20: 290–3

Handsfield HH, Dalu ZA, Martin DH, et al. Azythromycin Gonorrhoea study group: multicenter trial of single-dose azythromycin vs ceftriaxone in the treatment of uncomplicated gonorrhoea. Sex Transm Dis 1994; 21 107–11

Waugh MA. Open study of the safety and efficacy of a single oral dose of azithromycin for the treatment of uncomplicated gonorrhea in men and women. J Antimicrob Chemother 1993; 31 Suppl. E: 193–8

Steingrimsson O, Olafsson JH, Thorainsson H, et al. Single dose azithromycin treatment of gonorrhea and infection caused by C trachomatis and U urealyticum in men. Sex Transm Dis 1994; 21: 43–6

Martin DH, Mroczkowski TF, Dalu ZA, et al. A controlled trial of a single dose of azythromycin for the treatment of Chlamydial urethritis and cervicitis. N Engl J Med 1992; 327: 921–5

Worskowski KA, Johnson RB, Verdon M, et al. Azithromycin in chlamydial urethritis [letter]. JAMA 1993; 270: 1934–5

Worskowski KA, Hook EW, Handsfield HH. Single dose cefixime plus azithromycin in the treatment of uncomplicated gonorrhoea and chlamydial infection [abstract]. 32nd Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy; 1992 Oct 11–14; Anaheim (CA), 340

Edwards M, Rainwater K, Carter S, et al. Comparison of azythromycin and erythromycin for chlamydia cervicitis in pregnancy [abstract]. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1994; 84: 61–3

Bush MR, Rosa C. Azythromycin and erythromycin in the treatment of cervical chlamydial infection during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 1994; 84: 61–3

Crombleholme WR, Schachter J, Grossman M, et al. Amoxicillin therapy for Chlamydia trachomatis in pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1990; 75: 752–6

D’Allaire, Huddleston JF, Graves WL, et al. Initial and repeat screening for Chlamydia trachomatis during pregnancy. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol 1998; 6: 116–22

McGregor JA, French JI, Parker R, et al. Prevention of premature birth by screening and treatment for common genital tract infections. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1995; 173: 157–67

Donders GGG, De Wet GH, Hooft P, et al. Lactobacilli in Pap smears, genital infection and pregnancy. Am J Perinatol 1993; 3: 17–25

Struthers BJ. Metronidazole appears not to be a human teratogen: review of the literature. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol 1997; 5: 326–35

Hart G. Risk profiles and epidemiologic interrelationships of sexually transmitted diseases. Sex Transm Dis 1993; 20: 126–36

Simoes JA, Camargo RP, Giraldo PC, et al. Association between prenatal complications and bacterial vaginosis in Brazilian pregnant women. Second International Meeting on Bacterial Vaginosis; 1998 Sept 17–19; Aspen (CO), 30

Donders GGG. Microscopy of the bacterial vaginal flora on fresh vaginal smears. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol 1999; 7: 177–9

Donders GGG. Bacterial vaginosis during pregnancy: screen and treat [editorial]. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Med 1999; 83: 1–4

Hay PE, Lamont RF, Taylor-Robinson, et al. Abnormal bacterial flora colonisation of the genital tract and subsequent delivery and late miscarriage. BMJ 1994; 308: 295–8

Donders GGG, Van Bulck B, Caudron J, et al. Bacterial vaginosis and Mycoplasmata increase the risk of spontaneous first trimester abortion. Am J Obstet Gynecol. In press

Boris J, Pahlson C, Larsson P-G. Six years observation after successful treatment of bacterial vaginosis. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol 1997; 5: 297–302

Cook RL, Relondo-Lopez V, Schmitt C, et al. Clinical, microbiological and biochemical factors in recurrent bacterial vaginosis. J Clin Microbiol 1992; 30: 870–7

Moi H, Erkkola R, Jerve F, et al. Should male consorts of women with bacterial vaginosis be treated? Genitourin Med 1989; 65: 263–8

Hallen A, Jarstrand C, Pahlson C. Treatment of bacterial vaginosis with lactobacilli. Sex Transm Dis 1992; 19: 146–8

Hillier S, Krohn MA, Meyn L, et al. Recolonisation of the vagina with an exogenous strain of Lactobacillus crispatus. Second International Meeting on Bacterial Vaginosis; 1998 Sept 17–19; Aspen (CO), 18

Lugo-Miro VI, Green M, Mazur L. Comparison of different metronidazole therapeutic regimens for bacterial vaginosis: a meta-analysis. JAMA 1992; 268: 92–5

Dickerson MC, Johnston J, Delea TE, et al. The causal role for genital ulcer disease as a risk factor for transmission of human immunodeficiency virus. Sex Transm Dis 1996; 23(5): 429–40

Sewankambo N, Gray RH, Wawer MJ, et al. HIV-1 infection associated with abnormal vaginal flora morphology and bacterial vaginosis. Lancet 1997; 350: 546–50

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Professor J. Desmyter and Professor J. Verhaegen for their discussions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Donders, G.G.G. Treatment of Sexually Transmitted Bacterial Diseases in Pregnant Women. Drugs 59, 477–485 (2000). https://doi.org/10.2165/00003495-200059030-00005

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.2165/00003495-200059030-00005