Abstract

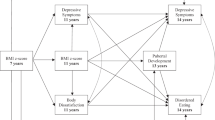

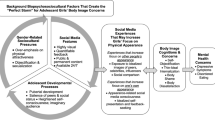

Objective

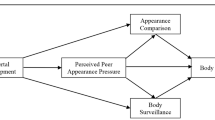

To explore the mechanisms through which early puberty is associated with psychological distress in women aged 18–25. This cross-sectional study aims to investigate whether body-related concerns and social interactions moderate or mediate this association.

Methods

Participants were compared on measures evaluating psychological distress, body image dysphoria, bulimic symptomatology and negative intimacy with best friend according to three pubertal timing groups: (1) “very early” puberty (menarche at 9 years old or less), (2) “early” puberty (menarche at 10 years old), and (3) “on-time” puberty (menarche between 11 and 13 years old). Forward stepwise multiple regressions and multiple mediation analysis were successively performed to see whether body-related concerns and peer interactions mediate or moderate the relationship between premature puberty and psychological distress.

Results

Controlling for age and ethnicity, results indicated (1) that women who began puberty “very early” had significantly higher levels of psychological distress than their “on-time” counterparts; (2) the association found between very early puberty and psychological distress was mediated by body image dysphoria and negative intimacy with best friend and was moderated by bulimic symptomatology. No mediational effect was found in women whose puberty was “early”.

Conclusion

These findings highlight the importance of using more than one group of early pubertal timing and the role of body and intimacy concerns in the explanation of psychological distress in women. Intervention strategies addressing the increased risk of psychological distress in women who begin puberty very early should target their body image and ability to form intimate friendships.

Résumé

Objectif

Explorer les mécanismes par lesquels la puberté précoce est associée à la détresse psychologique chez les femmes âgées de 18 à 25 ans. Cette étude transversale vise à déterminer si les préoccupations liées au corps et les interactions sociales modèrent ou médient cette association.

Méthodologie

Les participantes ont été contrastées sur des mesures évaluant la détresse psychologique, la dysphorie de l’image corporelle, la symptomatologie boulimique et l’intimité négative avec la meilleure amie selon trois groupes : (1) puberté « très précoce » (ménarche à 9 ans ou moins); (2) puberté « précoce » (ménarche à 10 ans) et (3) la puberté « synchrone » (ménarche entre 11 et 13 ans). Des régressions multiples pas à pas et des analyses de médiation multiples ont ensuite été effectuées pour déterminer si les préoccupations liées au corps et les interactions avec les pairs médiaient ou modéraient la relation entre la puberté précoce et la détresse psychologique.

Résultats

En contrôlant pour l’âge et l’appartenance ethnique, les résultats ont révélé : (1) que les femmes du groupe de puberté « très précoce » présentaient des niveaux de détresse psychologique significativement plus élevés que leurs homologues dont la puberté était « synchrone »; (2) l’association entre la puberté très précoce et la détresse psychologique était médiée par la dysphorie de l’image corporelle et l’intimité négative avec la meilleure amie et était modérée par la symptomatologie boulimique. Aucun effet médiateur n’a été identifié chez les femmes dont la puberté était « précoce ».

Conclusion

Ces résultats soulignent l’importance d’utiliser plus d’un groupe pour définir la puberté précoce et le rôle des préoccupations de corps et d’intimité dans l’explication de la détresse psychologique chez les femmes. Les stratégies d’intervention visant à contrer le risque accru de détresse psychologique chez les femmes pour qui la puberté commence très tôt devraient cibler leur image corporelle et leur capacité à nouer des relations d’amitiés.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Austin, S. B. (2012). A public health approach to eating disorders prevention: it’s time for public health professionals to take a seat at the table. BMC Public Health, 12, 854.

Benas, J. S., Uhrlass, D. J., & Gibb, B. E. (2010). Body dissatisfaction and weight-related teasing: a model of cognitive vulnerability to depression among women. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 41, 352–356.

Boyer, R., Préville, M., Légaré, G., & Valois, P. (1993). La détresse psychologique dans la population du Québec non institutionnalisée: résultats normatifs de l’Enquête Santé Québec. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 38, 339–343.

Brausch, A. M., & Gutierrez, P. M. (2009). The role of body image and disordered eating as risk factors for depression and suicidal ideation in adolescents. Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior, 39, 58–71.

Brendgen, M., Vitaro, F., & Bukowski, W. M. (2000). Deviant friends and early adolescents’ emotional and behavioral adjustment. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 10, 173–189.

Burt, V. K., & Stein, K. (2002). Epidemiology of depression throughout the female life cycle. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 63(Suppl 7), 9–15.

Camirand, H., Traoré, I., Baulne, J., & Courtemanche, R. (2016). L'enquête québécoise sur la santé de la population 2014-2015: pour en savoir plus sur la santé des Québécois: résultats de la deuxième édition. Institut de la statistique du Québec.

Cash, T. F. (2002). The situational inventory of body-image dysphoria: psychometric evidence and development of a short form. The International Journal of Eating Disorders, 32, 362–366.

Cash, T. F., Thériault, J., & Annis, N. M. (2004). Body image in an interpersonal context: Adult attachment, fear of intimacy and social anxiety. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 23, 89–103.

Cassano, P., & Fava, M. (2002). Depression and public health: An overview. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 53, 849–857.

Compian, L. J., Gowen, L. K., & Hayward, C. (2009). The interactive effects of puberty and peer victimization on weight concerns and depression symptoms among early adolescent girls. Journal of Early Adolescence, 29, 357–375.

Copeland, W., Shanahan, L., Miller, S., Costello, E. J., Angold, A., & Maughan, B. (2010a). Do the negative effects of early pubertal timing on adolescent girls continue into young adulthood? The American Journal of Psychiatry, 167, 1218–1225.

Copeland, W., Shanahan, L., Miller, S., Costello, E. J., Angold, A., & Maughan, B. (2010b). Outcomes of early pubertal timing in young women: a prospective population-based study. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 167, 1218–1225.

Cronbach, L. J. (1951). Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika, 16, 297–334.

Fergusson, D. M., Wanner, B., Vitaro, F., Horwood, L. J., & Swain-Campbell, N. (2003). Deviant peer affiliations and depression: confounding or causation? Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 31, 605–618.

Frey, L. L., Tobin, J., & Beesley, D. (2004). Relational predictors of psychological distress in women and men presenting for university counseling center services. Journal of College Counseling, 7, 129–139.

Garner, D. M., Olmsted, M. P., Bohr, Y., & Garfinkel, P. E. (1982). The eating attitudes test: psychometric features and clinical correlates. Psychological Medicine, 12, 871–878.

Ge, X., Natsuaki, M. N., Jin, R., & Biehl, M. C. (2011). A contextual amplification hypothesis: Pubertal timing and girls’ emotional and behavioral problems. In Understanding Girls’ Problem Behavior (pp. 9–29). Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470977453.ch1.

Gerner, B., & Wilson, P. H. (2005). The relationship between friendship factors and adolescent girls’ body image concern, body dissatisfaction, and restrained eating. The International Journal of Eating Disorders, 37, 313–320.

Graber, J. A. (2013). Pubertal timing and the development of psychopathology in adolescence and beyond. Hormones and Behavior, 64, 262–269.

Graber, J. A., Petersen, A. C., & Brooks-Gunn, A. C. (1996). Pubertal processes: Methods, measures, and models. In J. A. Graber, J. Brooks-Gunn, & A. C. Petersen (Eds.), Transitions through adolescence: Interpersonal domains and context (pp. 22–53). Hillsdale, NJ, US.

Graber, J. A., Seeley, J. R., Brooks-Gunn, J., & Lewinsohn, P. M. (2004). Is pubertal timing associated with psychopathology in young adulthood? Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 43, 718–726.

Gurreri, S., Thériault, J., & Boucher, S. (2018). L’indépendance émotionnelle à la mère et au père en lien avec la détresse psychologique chez les jeunes femmes. Psychologie Française. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psfr.2018.01.001.

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression based approach. New York City: Guilford Press.

Hoffman, J. A. (1984). Psychological separation of late adolescents from their parents. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 31, 170–178.

Ilfeld, F. W. (1976). Further validation of a psychiatric symptom index in a normal population. Psychological Reports, 39, 1215–1228.

Kaplowitz, P. B., Slora, E. J., Wasserman, R. C., Pedlow, S. E., & Herman-Giddens, M. E. (2001). Earlier onset of puberty in girls: Relation to increased body mass index and race. Pediatrics, 108, 347–353.

Lien, L., Dalgard, F., Heyerdahl, S., Thoresen, M., & Bjertness, E. (2006). The relationship between age of menarche and mental distress in Norwegian adolescent girls from different immigrant groups in Norway: Results from an urban city cross-sectional survey. Social Science & Medicine, 63, 285–295.

McNicholas, F., Dooley, B., McNamara, N., & Lennon, R. (2012). The impact of self-reported pubertal status and pubertal timing on disordered eating in Irish adolescents. European Eating Disorders Review, 20, 355–362.

Mendle, J., Turkheimer, E., & Emery, R. E. (2007). Detrimental psychological outcomes associated with early pubertal timing in adolescent girls. Developmental Review, 27, 151–171.

Michaud, P.-A., Suris, J.-C., & Deppen, A. (2006). Gender-related psychological and behavioural correlates of pubertal timing in a national sample of Swiss adolescents. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology, 254, 172–178.

Moradi, B., & Huang, Y.-P. (2008). Objectification theory and psychology of women: A decade of advances and future directions. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 32, 377–398.

Mrug, S., Elliott, M., Gilliland, M. J., Grunbaum, J. A., Tortolero, S. R., Cuccaro, P., & Schuster, M. (2008). Positive parenting and early puberty in girls: protective effects against aggressive behavior. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 162, 781–786.

Negriff, S., & Susman, E. J. (2011). Pubertal timing, depression, and externalizing problems: a framework, review, and examination of gender differences. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 21, 717–746.

Owens, M. D., Scofield, B. E., & Taylor, C. E. (2003). Incorporating mother-daughter groups within clinical settings to increase adolescent females’ self-esteem. Journal of Family Issues, 24, 895–907.

Patton, G. C., et al. (2007). Pubertal stage and deliberate self-harm in adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 46, 508–514.

Préville, M., Boyer, R., Potvin, L., Perrault, C., & Légaré, G. (1992). La détresse psychologique : détermination de la fiabilité et de la validité de la mesure utilisée dans l’enquête Santé Québec. Québec: Ministère de la Santé de des Services Sociaux.

Schaefer, M. T., & Olson, D. H. (1981). Assessing intimacy: The pair inventory. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 7, 47–60.

Schutz, H. K., & Paxton, S. J. (2007). Friendship quality, body dissatisfaction, dieting and disordered eating in adolescent girls. The British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 46, 67–83.

Seedat, S., Scott, K. M., Angermeyer, M. C., Berglund, P., Bromet, E. J., Brugha, T. S., ... & Karam, E. G. (2009). Cross-national associations between gender and mental disorders in the World Health Organization world mental health surveys. Archives of General Psychiatry, 66, 785–795.

Stattin, H., & Magnusson, D. (1990). Pubertal maturation in female development. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Stice, E., Hayward, C., Cameron, R. P., Killen, J. D., & Taylor, C. B. (2000). Body-image and eating disturbances predict onset of depression among female adolescents: A longitudinal study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 109, 438–444.

Sultan, C., et al. (2005). Expression clinique des précocités pubertaires chez la fille. Gynécologie, Obstétrique & Fertilité, 33, 197–207.

Thériault, J. (1998). Assessing intimacy with the best friend and the sexual partner during adolescence: The PAIR-M inventory. The Journal of Psychology, 132, 493–506.

Vallerand, R. J. (1989). Vers une méthodologie de validation trans-culturelle de questionnaires psychologiques: Implications pour la recherche en langue française. Canadian Psychology/Psychologie Canadienne, 30, 662–680.

Wu, T., Mendola, P., & Buck, G. M. (2002). Ethnic differences in the presence of secondary sex characteristics and menarche among US girls: the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988-1994. Pediatrics, 110, 752–757.

Funding

The research presented in this paper was funded by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (# 410-2006-2427).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

The study was approved by the University of Quebec in Montreal’s Research Ethics Board.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Sample size requirements

Confidence intervals for psychological distress for the “very early” and the “early” puberty groups

In our population, we expected the proportions of participants in the “very early” puberty group (menarche at 9 years old or less) and in the “early” puberty group (menarche at 10 years) to approximate 4% and 8%, respectively. In previous studies (Préville, Potvin, & Boyer, 1995), the standard deviation of psychological distress scores seems to vary between 20 and 25 units. For the “very early” puberty group, considering sample sizes varying from 126 to 196 women, a two-sided 95% confidence interval for psychological distress will extend the observed mean by 3.5 units on each side (assuming that the standard deviation will vary from 20 to 25 units, and using an asymptotic normal approximation). For the “early” puberty group, expecting twice as many women than in the “very early” group and using the same approach, a two-sided 95% confidence interval for psychological distress will extend the observed mean by 2.5 units on each side, with sample sizes varying from 252 to 392 women. These results mean that the number of women needed for the current study should be between 3150 and 4900 women, approximately, including 2772 to 4312 women in the “on-time” puberty group.

Power of testing for the effect of “very early” and “early” puberty on psychological distress

A multiple linear regression model that includes 10 covariates with a squared multiple correlation R2 of 0.10 and a sample size of 3150 (4900) women will have 95% power to detect (at a 0.01 significance level) an increase in R2 of 0.5% (0.3%), when including a dummy variable (0.1) representing early puberty.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Thériault, J., Otis, J., Hébert, M. et al. Exploring the mediating and moderating roles of body-related concerns and social interactions on the association between early puberty and psychological distress in young adult women. Can J Public Health 110, 606–615 (2019). https://doi.org/10.17269/s41997-019-00213-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.17269/s41997-019-00213-4