Self-injurious behaviour can be defined as the causing of intentional, direct damage to one's body tissue without suicidal intent. Reference Pattison and Kahan1 Common examples include cutting and burning of the skin. Reference Favazza and Conterio2–Reference Nijman, Dautzenberg, Merckelbach, Jung, Wessel and del Campo5 Because such behaviour is associated with suicide and psychiatric disorders, Reference Langbehn and Pfohl3,Reference Tantam and Whittaker6,Reference Skegg7 and because its treatment can be challenging, Reference Feldman8–Reference Kapur11 it has attracted substantial attention in both the clinical and research literature. Although the clinical correlates and functions of self-injurious behaviour have been studied extensively, Reference Skegg7,Reference Gratz12–Reference Klonsky15 little is known about its aetiology.

Many theorise that childhood sexual abuse has a primary aetiological role. For example, van der Kolk et al Reference van der Kolk, Perry and Herman16 (p. 1669) wrote that childhood trauma such as sexual abuse ‘contributes heavily to the initiation of self-destructive behaviour’. Wonderlich et al Reference Wonderlich, Donaldson, Carson, Staton, Gertz, Leach and Johnson17 (p. 203) suggested that individuals subjected to childhood sexual abuse ‘engage in a broad array of self-destructive behaviors that may serve to reduce emotional distress associated with their abuse’. Noll et al Reference Noll, Horowitz, Bonanno, Trickett and Putnam18 (p. 1467) proposed that sexually abused individuals who self-injure ‘may be reenacting the abuse perpetrated on them’. Cavanaugh Reference Cavanaugh19 (pp. 97, 99) described self-injurious behaviour as a ‘manifestation of sexual abuse’. Stone Reference Stone20 implicated sexual abuse by a male relative in the development of such behaviour. More recently, Yates Reference Yates21 theorised that sexual abuse and other childhood traumas cause emotional and relational vulnerabilities which in turn create the need for self-injurious behaviour as a maladaptive coping strategy.

Those who advocate an aetiological role of childhood sexual abuse point to the numerous studies that document a relationship between histories of such behaviour and self-injurious abuse. However, to characterise accurately the empirical relationship between the two variables it is necessary to take into account studies that find small or no associations, in addition to studies that find a positive association. As previous efforts to review the empirical literature on this topic have taken a narrative approach, Reference Mina and Gallop22 the meta-analysis reported here was conducted to systematically quantify the research findings on the relationship between a history of childhood sexual abuse and the development of self-injurious behaviour.

Method

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies reporting original research findings regarding the relationship between a history of childhood sexual abuse and self-injurious behaviour were included in this review. Studies in which all participants had histories of childhood sexual abuse or all participants had histories of self-injurious behaviour were excluded, since such studies could not provide measures of association between the two (e.g. Noll et al Reference Noll, Horowitz, Bonanno, Trickett and Putnam18 ). Studies examining self-injurious behaviour with suicidal intent, or that did not distinguish between such behaviour with and without suicidal intent, were also excluded from the meta-analysis (e.g. Romans et al; Reference Romans, Martin, Anderson, Herbison and Mullen23 Sansone et al; Reference Sansone, Gaither and Barclay24 Brown et al Reference Brown, Houck and Hadley25 ). Studies examining participants with developmental disabilities or psychosis were excluded. Finally, studies that examined childhood abuse without distinguishing between physical, sexual and other forms of abuse were excluded (e.g. Brodsky et al Reference Brodsky, Cloitre and Dulit26 ).

Search strategy

To identify appropriate studies, a literature search was conducted using three database sources: PubMed, PsycINFO, and the Web of Knowledge Science Citation and Social Science Citation Indices. Owing to ambiguity regarding terminology, multiple keywords were identified, and the following search string was used: (self-injury or self-injurious behaviour OR deliberate self-harm OR self-mutilation OR self-mutilative behaviour OR self-destructive) AND (sex abuse OR sexual abuse). Studies published up to the end of June 2006 were surveyed.

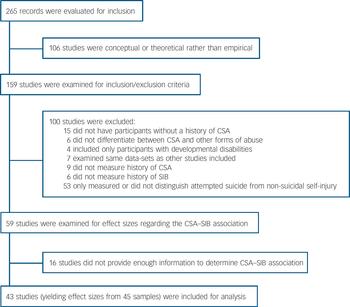

Our search strategy yielded 156 empirical English-language studies and these were obtained for further inspection regarding inclusion and exclusion criteria. Of these, 100 were excluded (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 QUOROM (Quality of Reporting of Meta-analyses) diagram (CSA, childhood sexual abuse; SIB, self-injurious behaviour).

The remaining 56 studies met inclusion criteria. However, for 16 of these there was not enough information to extract an effect size regarding the abuse–behaviour association and efforts to obtain the data from study authors were not successful. The remaining 40 studies with known effect sizes were retained for inclusion in the meta-analysis. We inspected the reference sections of studies meeting inclusion criteria to locate additional relevant studies that might have been missed by our search strategy; only three additional studies meeting inclusion criteria could be located, all of which were published before 1990. Reference Carroll, Schaffer, Spensley and Abramowitz27–Reference Schwartz, Cohen, Hoffman and Meeks29 Thus we concluded that our search strategy was sufficiently comprehensive and inclusive. Incorporating the three additional studies yielded a total of 43 studies Reference Nijman, Dautzenberg, Merckelbach, Jung, Wessel and del Campo5,Reference van der Kolk, Perry and Herman16,Reference Wonderlich, Donaldson, Carson, Staton, Gertz, Leach and Johnson17,Reference Carroll, Schaffer, Spensley and Abramowitz27–Reference Zweig-Frank, Paris and Guzder66 that met full inclusion criteria and were retained for the meta-analysis. These 43 studies contributed effect sizes from 45 independent samples.

Data analysis and study details

For each study in the meta-analysis, effect sizes indicating the relationship between childhood sexual abuse and self-injurious behaviour were extracted or converted to phi coefficient effect sizes. A phi coefficient is a measure of the degree of association between two dichotomous variables and its interpretation is comparable to other correlation coefficients. Methodological details of the 43 studies and 45 samples–including sample size, sample type and demographic variables–are presented in online Table DS1. Meta-analytic analyses were conducted with Comprehensive Meta-Analysis version 2.2.023 (Biostat; Englewood, New Jersey, USA). The effect sizes were examined for heterogeneity and the mean weighted aggregate effect size was computed, adopting a fixed-effects model in the case of a homogeneous distribution of effect sizes and a random-effects model in the case of a heterogeneous distribution. Potential continuous moderators (age, percentage female) of the aggregate effect size were examined with meta-regression and a categorical moderator (type of sample) was examined with an analogue of an analysis of variance procedure appropriate for effect size data. A fixed-effects model was used when the factors adequately explained the heterogeneity. When additional heterogeneity remained, a mixed-effects model was used.

Results

Table DS1 presents the results from 45 samples regarding the relationship between history of childhood sexual abuse and self-injurious behaviour. The mean weighted aggregate phi coefficient was 0.23 (95% CI 0.20–0.26) using a random effects model, and was significantly different from 0 (P<0.001). Phi coefficients ranged from 0.01 to 0.45 and the distribution exhibited significant heterogeneity (Q=90.47, P<0.001). Moderator analyses indicated that the magnitude of phi was not related to sample age or gender. Using a mixed-effects model, the type of sample was a significant moderator of the relationship between sexual abuse and self-injurious behaviour (Q (1, 39)=5.34, P<0.05). This relationship was stronger for the clinical samples (n=31; φ=0.24) than for the non-clinical samples (n=10; φ=0.18). For this latter analysis, four samples were excluded because they could not be discretely classified as either non-clinical or clinical. Reference Wonderlich, Donaldson, Carson, Staton, Gertz, Leach and Johnson17,Reference Wonderlich, Crosby, Mitchell, Thompson, Redlin, Demuth, Smyth and Haseltine30–Reference Tyler, Whitback, Hoyt and Johnson32

We examined the likelihood of publication bias by plotting the standard error as a function of Fisher's Z for each of the 45 effect sizes. On inspection the pattern indicated a lack of symmetry, whereby there were fewer smaller studies with smaller effect sizes in the group located for the review. Kendall's tau was significant (0.25, P<0.01), indicating an association between the treatment effect and the standard error. Similarly, Egger's test of the intercept was significant (t=4.82, P<0.001). Although these tests are useful for detecting a relationship between sample size and effect size, they cannot isolate the cause, only one of which is publication bias. The fail-safe N indicated that 5462 null studies would need to be located and included to nullify the effect found.

All studies that controlled for psychological risk factors found either minimal or negligible unique associations between childhood sexual abuse and self-injurious behaviour. Because different studies controlled for different variables, these results cannot be statistically aggregated and are thus described here qualitatively. Gratz et al Reference Gratz, Conrad and Roemer45 found that the abuse–behaviour relationship became non-significant when controlling for dissociation and several family environment variables (i.e. physical abuse, insecure attachment, emotional neglect and childhood separation), although the relationship remained marginally significant when analyses were limited to female participants. In contrast, Martin et al Reference Martin, Bergen, Richardson, Roeger and Allison51 found that the relationship remained statistically significant for male but not female participants when controlling for depression, hopelessness and family functioning. Zoroglu et al Reference Zoroglu, Tuzun, Sar, Tutkun, Savas, Ozturk, Alyanak and Kora65 found that childhood sexual abuse maintained a statistically significant association with self-injurious behaviour when controlling for dissociation, although the childhood variables neglect, physical abuse and emotional abuse all maintained larger unique associations with such behaviour than did sexual abuse.

All remaining studies that controlled for psychosocial variables found non-significant relationships between childhood sexual abuse and self-injurious behaviour. Evren & Evren Reference Evren and Evren39 found that childhood physical abuse (but not sexual abuse) maintained a significant association with self-injurious behaviour when controlling for demographic, family history, and clinical variables. Zlotnick et al Reference Zlotnick, Shea, Pearlstein, Simpson, Costello and Begin64 found that the abuse–behaviour association was no longer significant when controlling for dissociation, alexithymia and self-destructive behaviours. Zweig-Frank et al Reference Zweig-Frank, Paris and Guzder66 reported that the association became non-significant when controlling for family environment variables and a diagnosis of borderline personality disorder. Likewise, in Gladstone et al Reference Gladstone, Parker, Wilhelm, Malhi, Wilhelm and Austin41 the correlation became non-significant when controlling for borderline personality disorder. Finally, in Parker et al Reference Parker, Malhi, Mitchell, Kotze, Wilhelm and Parker54 the association became non-significant when controlling for maternal depression, suicidal ideation, current drug use and suicide attempt history.

Discussion

Our meta-analysis examined the association between a history of childhood sexual abuse and the development of self-injurious behaviour. Across 45 samples, the aggregate phi coefficient was 0.23, indicating a relatively small relationship between the two. These results suggest that childhood sexual abuse accounts for no more than 5% of the variance in the development of self-injurious behaviour. Therefore it is unlikely that childhood sexual abuse has a primary role in the development or maintenance of such behaviour.

Significantly, studies with smaller sample sizes tended to report larger relationships. For example, the median phi coefficient for samples with more than 125 participants was 0.21 (n=22), compared with a median of φ=0.33 (n=23) for samples with 125 or fewer participants. This result suggests the possibility of a bias towards publishing studies with statistically significant results, since studies with smaller sample sizes require larger effect sizes to achieve statistical significance. Indeed, formal analyses found evidence of publication bias, suggesting that smaller studies with positive findings were more likely to be published than smaller studies with null or negative findings.

Finally, childhood sexual abuse appears to explain little or no unique variance in self-injurious behaviour. In studies that controlled for variables such as family environment, dissociation, alexithymia, hopelessness and borderline personality disorder, the abuse–behaviour relationship became minimal or negligible. Reference Evren and Evren39,Reference Gratz, Conrad and Roemer45,Reference Martin, Bergen, Richardson, Roeger and Allison51,Reference Parker, Malhi, Mitchell, Kotze, Wilhelm and Parker54,Reference Zlotnick, Shea, Pearlstein, Simpson, Costello and Begin64,Reference Zweig-Frank, Paris and Guzder66 In addition, this relationship was stronger in clinical samples, in which multiple psychiatric risk factors are likely to be present. Taken as a whole, the pattern of findings suggests that childhood sexual abuse might be best conceptualised as a proxy risk factor for self-injurious behaviour. Reference Kraemer, Stice, Kazdin, Offord and Kupfer67 In other words, the two might be associated because they are correlated with the same psychiatric risk factors, as opposed to there being a unique or aetiological link between them. At the same time, in some cases childhood sexual abuse might contribute to the initiation of self-injurious behaviour through mediating variables such as depression, anxiety and self-derogation, each of which is known to relate to both childhood sexual abuse and self-injurious behaviour. Reference Klonsky, Oltmanns and Turkheimer13,Reference Rind, Tromovitch and Bauserman68,Reference Klonsky and Muehlenkamp69

Future directions

Variability in the conceptual and operational definitions used by the studies included in the meta-analysis suggests directions for future research. For example, self-injurious behaviour can manifest in many ways and it is possible that the method, frequency, medical severity or other aspects of such behaviour could moderate the abuse–behaviour relationship. Future research should examine this possibility. In addition, meta-analytic data indicate that the association between childhood sexual abuse and psychopathological symptoms tends to be larger for more severe forms of abuse. Reference Rind, Tromovitch and Bauserman68 Future studies should therefore give consideration to abuse parameters indicative of increased severity (e.g. coercion, frequency, relation to perpetrator, penetration). Initial attempts to examine the relationship of severity parameters to self-injurious behaviour have yielded mixed results. Reference Mina and Gallop22,Reference Boudewyn and Liem34,Reference Martin, Bergen, Richardson, Roeger and Allison51,Reference Zanarini, Yong, Frankenburg, Hennen, Reich, Marino and Vjuanovic63,Reference Zweig-Frank, Paris and Guzder66 If the most severe forms of childhood sexual abuse are examined, it is possible that the association with self-injurious behaviour might be larger than that reported in this meta-analysis. In the absence of such evidence, however, theories that childhood sexual abuse is a primary cause of such behaviour lack empirical justification.

Acknowledgements

Preparation of this paper was supported in part by National Research Service Award MH67299 from the National Institute of Mental Health and funding from the Office of the Vice President of Research at Stony Brook University.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.