-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

K. L. Haywood, A. M. Garratt, P. T. Dawes, Patient-assessed health in ankylosing spondylitis: a structured review, Rheumatology, Volume 44, Issue 5, May 2005, Pages 577–586, https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/keh549

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

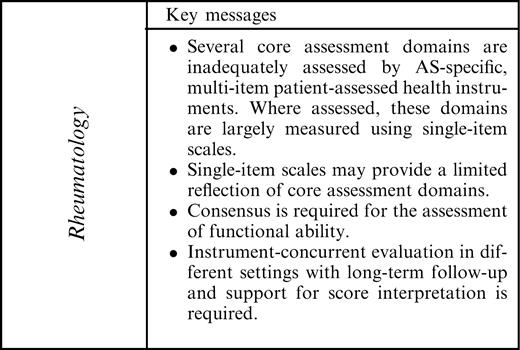

Objective. To review evidence relating to the measurement properties for all disease-specific, multi-item, patient-assessed health instruments in patients with ankylosing spondylitis (AS).

Methods. Systematic literature searches were made to identify instruments, using predefined criteria relating to reliability, validity, responsiveness and precision.

Results. Twelve AS-specific and three arthritis-specific instruments met the inclusion criteria. Three AS-specific instruments that measure health-related quality of life (HRQL) were reviewed. The Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI), the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index (BASFI) and the Dougados Functional Index (DFI) had the greatest amount of evidence for reliability, validity and responsiveness across a range of settings. Four instruments lacked evidence for test–retest or internal consistency reliability. Most were assessed for validity through comparisons with other instruments, global judgements of health, mobility or clinical and sociodemographic variables. Most were assessed for responsiveness through mean score changes. Three instruments lacked evidence of responsiveness.

Conclusion. This review provides a contribution to AS assessment. AS-specific multi-item measures specific to the assessment of pain, stiffness, fatigue and global health were not identified; where assessed, these domains were largely measured with single-item visual analogue scales. Single items may provide a limited reflection of these important domains. The BASFI and DFI remain the instruments of choice for functional assessment. HRQL is recommended as a core assessment domain. Further concurrent evaluation is recommended.

Ankylosing spondylitis (AS) is an incurable, inflammatory disease, primarily affecting the pelvis and spine, but often with involvement of peripheral joints, entheses and extra-articular sites [1]. Often affecting individuals from an early adult age, the disease can have a profound impact on life quality in terms of physical, social and psychological well-being [2]. It is widely accepted that the patients' perception of disease impact and the outcomes of health-care should be included in clinical trials and similar forms of evaluative study. This has resulted in a significant increase in the availability of patient-assessed health instruments which aim to measure aspects of health from the perspective of the patient [3]. Structured reviews of measurement properties and accompanying professional consensus are helpful in supporting instrument selection and standardization [3, 4].

To encompass the multidimensional impact of AS, five core evaluative domains and, with the exception of functional disability, associated single-item scales have been recommended by the Assessment in AS International Working Group (ASAS; www.asas-group.org): pain [intensity; visual analogue scale (VAS)], spinal stiffness/inflammation (morning stiffness duration; VAS), functional ability [Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index (BASFI) [5] or Dougados Functional Index (DFI) [6]], patient global assessment of health status (VAS; last week) and spinal mobility [7, 8]. Instrument selection was informed by a literature review (1988–1995; Medline database and citation searches), expert opinion and professional consensus agreement.

Single items, such as those recommended by ASAS, may not allow patients to appropriately report the wide impact of disease or treatment, providing a limited reflection of health [4]. The resulting summary judgement of health status limits measurement validity and score interpretation [4, 9]. Patient-assessed health instruments usually take the form of questionnaires containing multiple items, or questions, to reflect the broad nature of health status, disease or injury [3, 4]. These instruments aim to provide an accurate assessment of health or disease from the patient's perspective, which contribute to validity and score interpretation [3, 4, 9]. This structured review presents an updated and more extensive review of published evidence for AS- and arthritis-specific multi-item, patient-assessed instruments that measure any aspect of health or health-related quality of life (HRQL) in this disease (1988–2004). The review will inform instrument selection and future research within this field.

Methods

Identification of studies

The search strategy was designed to retrieve references relating to the development and evaluation of multi-item patient-assessed health instruments, including reviews. The first AS-specific patient-assessed health instrument was developed in 1988 [6], so the search strategy was restricted to the period from 1988 to August 2004. All searches included terms specific to AS combined with the measurement of health outcome and instrument measurement properties [4, 10]. Search strategies used medical subject headings (MeSH terms) and free text searching. Further searches used names of identified instruments.

Databases searched included AMED, CINAHL, the Cochrane Controlled Trials Register, EMBASE, Medline and Psychlit. The Patient-assessed Health Instruments (PHI) bibliographic database (http://phi.uhce.ox.ac.uk/), hosted by the National Centre for Health Outcomes Development at the University of Oxford, was also searched. This database is based on systematic searches of the literature and contains over 7000 records relating to published instrument evaluations found on the major electronic databases (from database inception to September 2003) [3].

The reference lists of included articles were reviewed for additional articles. Relevant journals were hand-searched, including Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases, Arthritis and Rheumatism, Rheumatology and the Journal of Rheumatology. Texts and compendia were consulted [11–13]. The reference lists of existing reviews [8, 14–17] and manuscripts discussing the clinical management of AS [18, 19] were also reviewed.

Inclusion criteria

Titles and abstracts of all articles were assessed for inclusion/exclusion by two independent reviewers (K.L.H., A.M.G.) and agreement was checked. Published articles were included if they provided evidence of measurement properties for AS or arthritis-specific, multi-item, patient-assessed health instruments following completion by adults with AS. Generic or domain-specific multi-item instruments (not specific to AS or arthritis) were excluded. Clinician-assessed instruments, single-item and mobility measures, radiographic and imaging techniques were excluded. The review included instrument evaluations in non-English-speaking populations that were published in an English language journal. Instruments without evidence of reliability or validity were excluded.

Data extraction

Data extraction followed predefined criteria considered important in the evaluation of patient-assessed health instruments [4, 9, 11] and included patient characteristics, type of instrument, the domain focus, scaling, length, and evidence of measurement properties. The summary of evidence follows that of previous reviews [10, 11].

Evidence for measurement properties was assessed using accepted criteria [4, 9, 11]. Reliability assesses measurement stability over time, and for multi-item instruments, internal consistency [4, 9]. Test–retest reliability assesses score temporal stability and is assessed following instrument completion at two time points; it assumes no change in underlying condition [4]. Internal consistency reliability assesses the ability of items to measure a single underlying domain, and is assessed following a single application. Evidence for test–retest and internal consistency reliability, specifically test–retest correlation coefficients and Cronbach's α, are presented. The reliability estimate reflects two components: a true score and an underlying level of error [9]. Reliability estimates range between 0 and 1.0; the closer the score to 1.0, the lower the error [4, 9]. The reliability of an instrument has implications for whether it is suitable for application in group or individual evaluation. For the evaluation of individuals high levels of reliability, above 0.90, have been recommended [4, 9]. For group comparisons, levels over 0.70 are recommended [9].

Validity assesses whether an instrument measures what is intended [4], and is referred to as ‘truth’ within the OMERACT filter [20]. Content and face validity are assessed through an appraisal of item content; evidence for the source of instrument items. Evidence for these forms of qualitative validity is presented. Evidence for external construct validity requires comparison of instrument scores with those for other measures of health, clinical, socio-demographic and health service use variables [4, 10]. Construct validity may also be assessed by group or divergent validity, where, based on theory or existing evidence, we can state that one group will possess more or less of a construct [9]. For example, compared with the general population, people with AS may be expected to report greater levels of pain and worse HRQL. The results of these comparisons are presented. Evidence derived from statistical methods such as factor analysis to describe instrument dimensionality or internal construct validity is presented [4].

Responsiveness has been described as the ability of an instrument to measure clinically important change over time when change is present [4], and is a necessary property of instruments intended for application in evaluative studies [21, 22]. Two broad approaches to evaluating responsiveness include those that are distribution-based and those that are anchor-based. Distribution-based approaches relate changes in instrument score to some measure of variability, the most common being the effect size statistic [4]. Effect size statistics provide a standardized unit of expression of the size and meaning of score change, supporting the comparison of instrument performance; the most responsive instruments have larger effect sizes. Anchor-based approaches assess the relationship between changes in instrument score and an external variable [23]. This includes health transition items or global judgements of change. Responses to transition items have also been compared to instrument score change using correlation. Data extraction covered the full range of approaches to measuring responsiveness and included descriptive statistics.

Data summary

The summary of reviewed evidence was informed by previous instrument reviews [11, 24, 25] (Table 1). The thoroughness (that is, the range of evaluations) and results of evaluations are considered separately. A summary scale from 0 to +++ is presented, where 0 is no evidence for the underlying criteria and +++ indicates a wide range of testing and good evidence of measurement properties (Table 1).

Grading scale for summary of evidence for instrument reliability, validity and responsiveness (adapted from McDowell and Newell [11])

| Thoroughness of evaluation . | . | Results of evaluation . | . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | No published evidence | 0 | No published numerical results | ||

| + | Basic information only | + | Weak evidence only | ||

| ++ | Several types of test, or several evaluations in different populations | ++ | Moderate evidence | ||

| +++ | All major forms of validity/ reliability/responsiveness reported. Several good quality evaluations in different populations | +++ | Strong evidence | ||

| Thoroughness of evaluation . | . | Results of evaluation . | . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | No published evidence | 0 | No published numerical results | ||

| + | Basic information only | + | Weak evidence only | ||

| ++ | Several types of test, or several evaluations in different populations | ++ | Moderate evidence | ||

| +++ | All major forms of validity/ reliability/responsiveness reported. Several good quality evaluations in different populations | +++ | Strong evidence | ||

Grading scale for summary of evidence for instrument reliability, validity and responsiveness (adapted from McDowell and Newell [11])

| Thoroughness of evaluation . | . | Results of evaluation . | . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | No published evidence | 0 | No published numerical results | ||

| + | Basic information only | + | Weak evidence only | ||

| ++ | Several types of test, or several evaluations in different populations | ++ | Moderate evidence | ||

| +++ | All major forms of validity/ reliability/responsiveness reported. Several good quality evaluations in different populations | +++ | Strong evidence | ||

| Thoroughness of evaluation . | . | Results of evaluation . | . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | No published evidence | 0 | No published numerical results | ||

| + | Basic information only | + | Weak evidence only | ||

| ++ | Several types of test, or several evaluations in different populations | ++ | Moderate evidence | ||

| +++ | All major forms of validity/ reliability/responsiveness reported. Several good quality evaluations in different populations | +++ | Strong evidence | ||

Results

Identification of studies

The literature searches produced 138 articles covering 12 AS-specific and three arthritis-specific multi-item, patient-assessed health instruments with evidence of reliability or validity following completion by patients with AS (Table 2).

AS-specific patient-assessed health instruments

| Instrument . | Developer . | Domains (items) . | Response scale . | Score . | Origin . | Translations . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symptoms and disease activity | ||||||||||||

| Bath AS Disease Activity Index (BASDAI) | Garrett et al. (1994) [28] | Disease activity (6) | VAS; adjectival anchors | 0–10; 0 disease activity | UK | Multiple | ||||||

| Body Chart | Dziedzic (1997) [29] | Pain (1) | 4-point descriptive | No max score; 0 no pain | UK | – | ||||||

| Function | – | |||||||||||

| ASAQ | Nemeth et al. (1987) [37] | Function/spinal mobility (2) | 8-point adjectival | 0–11; 0 best function | UK | – | ||||||

| BASFI | Calin et al. (1994) [5] | Function (10) | VAS; adjectival anchors | 0–10; 0 best function | UK | Multiple | ||||||

| DFI | Dougados et al. (1988) [6] | Function (20) | 3-point categorical (revised to 5-point) | 0–40; 0 best function | France | Multiple | ||||||

| HAQa | Fries (1980) 32 | Arthritis-specific (core): Disability (20), Discomfort (1) | 4-point categorical; 1 × 15 cm VAS | 0–3; 0 best function 0–3; 0 no pain | USA | Multiple | ||||||

| HAQ-S | Daltroy et al. (1990) [33] | (HAQ + AS-specific items) Disability (23), Discomfort (2) | 4-point categorical; 2 × 15 cm VAS | 0–3; 0 best function 0–3; 0 no pain | USA/UK | Dutch | ||||||

| RLDQ | Abbott et al. (1994) [38] | Function (16) | 4-point categorical | 0–48; 0 best function | UK | Swedish | ||||||

| Global well-being | – | |||||||||||

| BAS-G | Jones et al. (1996) [30] | Global well-being (2) | VAS; adjectival anchors | 0–10; 0 best well-being | UK | – | ||||||

| Health-related quality of life | ||||||||||||

| ASQoL | Doward et al. (2003) [39] | HRQL (18) | Yes/No | 0–18; 0 best HRQL | UK, NL | Dutch | ||||||

| AIMSa | Meenan et al. (1980) [40] | 9 domains (45) | 2–6 point categorical | 0–10; 0 best health | USA | Multiple | ||||||

| AIMS2a | Meenan et al. (1992) [41] | 12 domains (57) | 5 point categorical | 0–10; 0 best health | USA | – | ||||||

| AS-AIMS2 | Guillemin et al. (1999) [31] | 13 domains (63) | 5 point categorical | 0–10; 0 best health | France | – | ||||||

| PETb | Bakker et al. (1995) [34] | Single index (15) | 7-point descriptive | 0–49; 0 best health | Canada/NL | – | ||||||

| PGI | Haywood et al. (2003) [36] | Single index (7) | 10-point descriptive plus weighting | 0–10; 10 best HRQL | UK | – | ||||||

| Instrument . | Developer . | Domains (items) . | Response scale . | Score . | Origin . | Translations . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symptoms and disease activity | ||||||||||||

| Bath AS Disease Activity Index (BASDAI) | Garrett et al. (1994) [28] | Disease activity (6) | VAS; adjectival anchors | 0–10; 0 disease activity | UK | Multiple | ||||||

| Body Chart | Dziedzic (1997) [29] | Pain (1) | 4-point descriptive | No max score; 0 no pain | UK | – | ||||||

| Function | – | |||||||||||

| ASAQ | Nemeth et al. (1987) [37] | Function/spinal mobility (2) | 8-point adjectival | 0–11; 0 best function | UK | – | ||||||

| BASFI | Calin et al. (1994) [5] | Function (10) | VAS; adjectival anchors | 0–10; 0 best function | UK | Multiple | ||||||

| DFI | Dougados et al. (1988) [6] | Function (20) | 3-point categorical (revised to 5-point) | 0–40; 0 best function | France | Multiple | ||||||

| HAQa | Fries (1980) 32 | Arthritis-specific (core): Disability (20), Discomfort (1) | 4-point categorical; 1 × 15 cm VAS | 0–3; 0 best function 0–3; 0 no pain | USA | Multiple | ||||||

| HAQ-S | Daltroy et al. (1990) [33] | (HAQ + AS-specific items) Disability (23), Discomfort (2) | 4-point categorical; 2 × 15 cm VAS | 0–3; 0 best function 0–3; 0 no pain | USA/UK | Dutch | ||||||

| RLDQ | Abbott et al. (1994) [38] | Function (16) | 4-point categorical | 0–48; 0 best function | UK | Swedish | ||||||

| Global well-being | – | |||||||||||

| BAS-G | Jones et al. (1996) [30] | Global well-being (2) | VAS; adjectival anchors | 0–10; 0 best well-being | UK | – | ||||||

| Health-related quality of life | ||||||||||||

| ASQoL | Doward et al. (2003) [39] | HRQL (18) | Yes/No | 0–18; 0 best HRQL | UK, NL | Dutch | ||||||

| AIMSa | Meenan et al. (1980) [40] | 9 domains (45) | 2–6 point categorical | 0–10; 0 best health | USA | Multiple | ||||||

| AIMS2a | Meenan et al. (1992) [41] | 12 domains (57) | 5 point categorical | 0–10; 0 best health | USA | – | ||||||

| AS-AIMS2 | Guillemin et al. (1999) [31] | 13 domains (63) | 5 point categorical | 0–10; 0 best health | France | – | ||||||

| PETb | Bakker et al. (1995) [34] | Single index (15) | 7-point descriptive | 0–49; 0 best health | Canada/NL | – | ||||||

| PGI | Haywood et al. (2003) [36] | Single index (7) | 10-point descriptive plus weighting | 0–10; 10 best HRQL | UK | – | ||||||

aArthritis-specific instruments; binterview-administered.

AS-specific patient-assessed health instruments

| Instrument . | Developer . | Domains (items) . | Response scale . | Score . | Origin . | Translations . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symptoms and disease activity | ||||||||||||

| Bath AS Disease Activity Index (BASDAI) | Garrett et al. (1994) [28] | Disease activity (6) | VAS; adjectival anchors | 0–10; 0 disease activity | UK | Multiple | ||||||

| Body Chart | Dziedzic (1997) [29] | Pain (1) | 4-point descriptive | No max score; 0 no pain | UK | – | ||||||

| Function | – | |||||||||||

| ASAQ | Nemeth et al. (1987) [37] | Function/spinal mobility (2) | 8-point adjectival | 0–11; 0 best function | UK | – | ||||||

| BASFI | Calin et al. (1994) [5] | Function (10) | VAS; adjectival anchors | 0–10; 0 best function | UK | Multiple | ||||||

| DFI | Dougados et al. (1988) [6] | Function (20) | 3-point categorical (revised to 5-point) | 0–40; 0 best function | France | Multiple | ||||||

| HAQa | Fries (1980) 32 | Arthritis-specific (core): Disability (20), Discomfort (1) | 4-point categorical; 1 × 15 cm VAS | 0–3; 0 best function 0–3; 0 no pain | USA | Multiple | ||||||

| HAQ-S | Daltroy et al. (1990) [33] | (HAQ + AS-specific items) Disability (23), Discomfort (2) | 4-point categorical; 2 × 15 cm VAS | 0–3; 0 best function 0–3; 0 no pain | USA/UK | Dutch | ||||||

| RLDQ | Abbott et al. (1994) [38] | Function (16) | 4-point categorical | 0–48; 0 best function | UK | Swedish | ||||||

| Global well-being | – | |||||||||||

| BAS-G | Jones et al. (1996) [30] | Global well-being (2) | VAS; adjectival anchors | 0–10; 0 best well-being | UK | – | ||||||

| Health-related quality of life | ||||||||||||

| ASQoL | Doward et al. (2003) [39] | HRQL (18) | Yes/No | 0–18; 0 best HRQL | UK, NL | Dutch | ||||||

| AIMSa | Meenan et al. (1980) [40] | 9 domains (45) | 2–6 point categorical | 0–10; 0 best health | USA | Multiple | ||||||

| AIMS2a | Meenan et al. (1992) [41] | 12 domains (57) | 5 point categorical | 0–10; 0 best health | USA | – | ||||||

| AS-AIMS2 | Guillemin et al. (1999) [31] | 13 domains (63) | 5 point categorical | 0–10; 0 best health | France | – | ||||||

| PETb | Bakker et al. (1995) [34] | Single index (15) | 7-point descriptive | 0–49; 0 best health | Canada/NL | – | ||||||

| PGI | Haywood et al. (2003) [36] | Single index (7) | 10-point descriptive plus weighting | 0–10; 10 best HRQL | UK | – | ||||||

| Instrument . | Developer . | Domains (items) . | Response scale . | Score . | Origin . | Translations . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symptoms and disease activity | ||||||||||||

| Bath AS Disease Activity Index (BASDAI) | Garrett et al. (1994) [28] | Disease activity (6) | VAS; adjectival anchors | 0–10; 0 disease activity | UK | Multiple | ||||||

| Body Chart | Dziedzic (1997) [29] | Pain (1) | 4-point descriptive | No max score; 0 no pain | UK | – | ||||||

| Function | – | |||||||||||

| ASAQ | Nemeth et al. (1987) [37] | Function/spinal mobility (2) | 8-point adjectival | 0–11; 0 best function | UK | – | ||||||

| BASFI | Calin et al. (1994) [5] | Function (10) | VAS; adjectival anchors | 0–10; 0 best function | UK | Multiple | ||||||

| DFI | Dougados et al. (1988) [6] | Function (20) | 3-point categorical (revised to 5-point) | 0–40; 0 best function | France | Multiple | ||||||

| HAQa | Fries (1980) 32 | Arthritis-specific (core): Disability (20), Discomfort (1) | 4-point categorical; 1 × 15 cm VAS | 0–3; 0 best function 0–3; 0 no pain | USA | Multiple | ||||||

| HAQ-S | Daltroy et al. (1990) [33] | (HAQ + AS-specific items) Disability (23), Discomfort (2) | 4-point categorical; 2 × 15 cm VAS | 0–3; 0 best function 0–3; 0 no pain | USA/UK | Dutch | ||||||

| RLDQ | Abbott et al. (1994) [38] | Function (16) | 4-point categorical | 0–48; 0 best function | UK | Swedish | ||||||

| Global well-being | – | |||||||||||

| BAS-G | Jones et al. (1996) [30] | Global well-being (2) | VAS; adjectival anchors | 0–10; 0 best well-being | UK | – | ||||||

| Health-related quality of life | ||||||||||||

| ASQoL | Doward et al. (2003) [39] | HRQL (18) | Yes/No | 0–18; 0 best HRQL | UK, NL | Dutch | ||||||

| AIMSa | Meenan et al. (1980) [40] | 9 domains (45) | 2–6 point categorical | 0–10; 0 best health | USA | Multiple | ||||||

| AIMS2a | Meenan et al. (1992) [41] | 12 domains (57) | 5 point categorical | 0–10; 0 best health | USA | – | ||||||

| AS-AIMS2 | Guillemin et al. (1999) [31] | 13 domains (63) | 5 point categorical | 0–10; 0 best health | France | – | ||||||

| PETb | Bakker et al. (1995) [34] | Single index (15) | 7-point descriptive | 0–49; 0 best health | Canada/NL | – | ||||||

| PGI | Haywood et al. (2003) [36] | Single index (7) | 10-point descriptive plus weighting | 0–10; 10 best HRQL | UK | – | ||||||

aArthritis-specific instruments; binterview-administered.

Patient characteristics

The number of respondents ranged from 14 [26] to 4282 [27]. All patients had a clinical diagnosis of AS. Mean respondent ages ranged from 30 to 57 yr. Mean disease duration ranged from 5.5 to 32.4 yr.

Patient-assessed health instruments

The Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI) [28], BASFI [5] and DFI [6] have undergone the greatest amount of testing for all measurement properties, with 72, 70 and 46 published articles respectively (Table 3).

Summary of evaluations for AS- and arthritis-specific patient-assessed health instruments

| . | Published evaluations (n)a . | . | . | . | . | Summary of measurement propertiesc . | . | . | . | . | . | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | . | . | . | Responsivenessb . | . | Reliability . | . | Validity . | . | Responsiveness . | . | |||||||||||

| Instrument . | Total . | Reliability . | Validity . | PT (UC) . | DT . | Thoroughness . | Results . | Thoroughness . | Results . | Thoroughness . | Results . | |||||||||||

| Symptoms and disease activity | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| BASDAI | 72 | 17 | 37 | 15 (3) | 25 | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | |||||||||||

| Body Chart | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 (2) | 0 | + | + | ++ | + | + | + | |||||||||||

| Function | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| ASAQ | 6 | 1 | 6 | 0 | 0 | + | + | ++ | + | 0 | 0 | |||||||||||

| BASFI | 70 | 19 | 29 | 18 | 26 | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | |||||||||||

| DFI | 46 | 16 | 18 | 15 (1) | 14 | ++ | ++ | +++ | ++ | +++ | ++ | |||||||||||

| HAQ | 5 | 0 | 3 | 1 (1) | 2 | 0 | 0 | + | + | ++ | + | |||||||||||

| HAQ-S | 22 | 4 | 13 | 10 (2) | 2 | + | + | +++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | |||||||||||

| RLDQ | 7 | 6 | 6 | 3 (1) | 0 | +++ | +++ | ++ | ++ | + | + | |||||||||||

| Global well-being | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| BAS-G | 18 | 4 | 9 | 8 | 4 | ++ | ++ | ++ | + | ++ | ++ | |||||||||||

| Health-related quality of life | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| ASQoL | 10 | 4 | 6 | 2 (3) | 2 | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | |||||||||||

| AIMS | 8 | 0 | 7 | 2 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | ++ | + | + | + | |||||||||||

| AIMS2 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | + | + | 0 | 0 | |||||||||||

| AS-AIMS2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | + | + | + | + | 0 | 0 | |||||||||||

| PET | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ++ | + | + | + | |||||||||||

| PGI | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 (1) | 0 | + | ++ | ++ | ++ | + | + | |||||||||||

| . | Published evaluations (n)a . | . | . | . | . | Summary of measurement propertiesc . | . | . | . | . | . | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | . | . | . | Responsivenessb . | . | Reliability . | . | Validity . | . | Responsiveness . | . | |||||||||||

| Instrument . | Total . | Reliability . | Validity . | PT (UC) . | DT . | Thoroughness . | Results . | Thoroughness . | Results . | Thoroughness . | Results . | |||||||||||

| Symptoms and disease activity | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| BASDAI | 72 | 17 | 37 | 15 (3) | 25 | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | |||||||||||

| Body Chart | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 (2) | 0 | + | + | ++ | + | + | + | |||||||||||

| Function | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| ASAQ | 6 | 1 | 6 | 0 | 0 | + | + | ++ | + | 0 | 0 | |||||||||||

| BASFI | 70 | 19 | 29 | 18 | 26 | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | |||||||||||

| DFI | 46 | 16 | 18 | 15 (1) | 14 | ++ | ++ | +++ | ++ | +++ | ++ | |||||||||||

| HAQ | 5 | 0 | 3 | 1 (1) | 2 | 0 | 0 | + | + | ++ | + | |||||||||||

| HAQ-S | 22 | 4 | 13 | 10 (2) | 2 | + | + | +++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | |||||||||||

| RLDQ | 7 | 6 | 6 | 3 (1) | 0 | +++ | +++ | ++ | ++ | + | + | |||||||||||

| Global well-being | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| BAS-G | 18 | 4 | 9 | 8 | 4 | ++ | ++ | ++ | + | ++ | ++ | |||||||||||

| Health-related quality of life | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| ASQoL | 10 | 4 | 6 | 2 (3) | 2 | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | |||||||||||

| AIMS | 8 | 0 | 7 | 2 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | ++ | + | + | + | |||||||||||

| AIMS2 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | + | + | 0 | 0 | |||||||||||

| AS-AIMS2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | + | + | + | + | 0 | 0 | |||||||||||

| PET | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ++ | + | + | + | |||||||||||

| PGI | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 (1) | 0 | + | ++ | ++ | ++ | + | + | |||||||||||

aTotal number of published instrument evaluations following completion by patients with AS.

bPT, physiotherapy intervention; UC, usual care; DT, drug therapy.

cSummary of evidence (after McDowell and Newell, 1996 [11]). Thoroughness: 0, no published evidence; +, basic information; ++, several types of test or several evaluations in different populations; +++, all major forms of reliability/validity/responsiveness reported. Several good-quality evaluations in different populations. Results: 0, no published results; +, weak evidence; ++, moderate evidence; +++, strong evidence of reliability/validity/responsiveness across a range of settings/interventions.

Summary of evaluations for AS- and arthritis-specific patient-assessed health instruments

| . | Published evaluations (n)a . | . | . | . | . | Summary of measurement propertiesc . | . | . | . | . | . | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | . | . | . | Responsivenessb . | . | Reliability . | . | Validity . | . | Responsiveness . | . | |||||||||||

| Instrument . | Total . | Reliability . | Validity . | PT (UC) . | DT . | Thoroughness . | Results . | Thoroughness . | Results . | Thoroughness . | Results . | |||||||||||

| Symptoms and disease activity | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| BASDAI | 72 | 17 | 37 | 15 (3) | 25 | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | |||||||||||

| Body Chart | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 (2) | 0 | + | + | ++ | + | + | + | |||||||||||

| Function | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| ASAQ | 6 | 1 | 6 | 0 | 0 | + | + | ++ | + | 0 | 0 | |||||||||||

| BASFI | 70 | 19 | 29 | 18 | 26 | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | |||||||||||

| DFI | 46 | 16 | 18 | 15 (1) | 14 | ++ | ++ | +++ | ++ | +++ | ++ | |||||||||||

| HAQ | 5 | 0 | 3 | 1 (1) | 2 | 0 | 0 | + | + | ++ | + | |||||||||||

| HAQ-S | 22 | 4 | 13 | 10 (2) | 2 | + | + | +++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | |||||||||||

| RLDQ | 7 | 6 | 6 | 3 (1) | 0 | +++ | +++ | ++ | ++ | + | + | |||||||||||

| Global well-being | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| BAS-G | 18 | 4 | 9 | 8 | 4 | ++ | ++ | ++ | + | ++ | ++ | |||||||||||

| Health-related quality of life | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| ASQoL | 10 | 4 | 6 | 2 (3) | 2 | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | |||||||||||

| AIMS | 8 | 0 | 7 | 2 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | ++ | + | + | + | |||||||||||

| AIMS2 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | + | + | 0 | 0 | |||||||||||

| AS-AIMS2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | + | + | + | + | 0 | 0 | |||||||||||

| PET | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ++ | + | + | + | |||||||||||

| PGI | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 (1) | 0 | + | ++ | ++ | ++ | + | + | |||||||||||

| . | Published evaluations (n)a . | . | . | . | . | Summary of measurement propertiesc . | . | . | . | . | . | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | . | . | . | Responsivenessb . | . | Reliability . | . | Validity . | . | Responsiveness . | . | |||||||||||

| Instrument . | Total . | Reliability . | Validity . | PT (UC) . | DT . | Thoroughness . | Results . | Thoroughness . | Results . | Thoroughness . | Results . | |||||||||||

| Symptoms and disease activity | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| BASDAI | 72 | 17 | 37 | 15 (3) | 25 | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | |||||||||||

| Body Chart | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 (2) | 0 | + | + | ++ | + | + | + | |||||||||||

| Function | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| ASAQ | 6 | 1 | 6 | 0 | 0 | + | + | ++ | + | 0 | 0 | |||||||||||

| BASFI | 70 | 19 | 29 | 18 | 26 | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | |||||||||||

| DFI | 46 | 16 | 18 | 15 (1) | 14 | ++ | ++ | +++ | ++ | +++ | ++ | |||||||||||

| HAQ | 5 | 0 | 3 | 1 (1) | 2 | 0 | 0 | + | + | ++ | + | |||||||||||

| HAQ-S | 22 | 4 | 13 | 10 (2) | 2 | + | + | +++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | |||||||||||

| RLDQ | 7 | 6 | 6 | 3 (1) | 0 | +++ | +++ | ++ | ++ | + | + | |||||||||||

| Global well-being | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| BAS-G | 18 | 4 | 9 | 8 | 4 | ++ | ++ | ++ | + | ++ | ++ | |||||||||||

| Health-related quality of life | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| ASQoL | 10 | 4 | 6 | 2 (3) | 2 | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | |||||||||||

| AIMS | 8 | 0 | 7 | 2 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | ++ | + | + | + | |||||||||||

| AIMS2 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | + | + | 0 | 0 | |||||||||||

| AS-AIMS2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | + | + | + | + | 0 | 0 | |||||||||||

| PET | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ++ | + | + | + | |||||||||||

| PGI | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 (1) | 0 | + | ++ | ++ | ++ | + | + | |||||||||||

aTotal number of published instrument evaluations following completion by patients with AS.

bPT, physiotherapy intervention; UC, usual care; DT, drug therapy.

cSummary of evidence (after McDowell and Newell, 1996 [11]). Thoroughness: 0, no published evidence; +, basic information; ++, several types of test or several evaluations in different populations; +++, all major forms of reliability/validity/responsiveness reported. Several good-quality evaluations in different populations. Results: 0, no published results; +, weak evidence; ++, moderate evidence; +++, strong evidence of reliability/validity/responsiveness across a range of settings/interventions.

The shortest instruments were the Body Chart [29] and the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Global score (BAS-G) [30], with one and two items respectively, although a single item is often reported for the BAS-G (Table 1). The longest was the AS-specific Arthritis Impact Measurement Scale (63 items) [31]. Most instruments produce index scores; that is, item scores are summed to produce a single score. The Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ) [32] and the HAQ-S [33] produce profile scores; that is, item scores are summed within separate domains, providing a reflection of health across these domains. The Patient Elicitation Technique (PET) [34, 35] and Patient-Generated Index (PGI) [36] are individualized measures. With the exception of the PET, which requires interview administration [35], all instruments have been self-completed.

Instruments are grouped in Tables 2 and 3 according to the domains that they purport to measure: symptoms and disease activity (BASDAI, Body Chart); function [Assessment in Ankylosing Spondylitis Questionnaire (ASAQ) [37], BASFI [5], DFI [6], HAQ [32], HAQ-S [33] and the Revised Leeds Disability Questionnaire (RLDQ) [38]]; global well-being (BAS-G [30]); and HRQL (ASQoL [39], AIMS [40], AIMS2 [41], AS-AIMS2 [31], PET [35] and PGI [36]).

AS- or arthritis-specific, multi-item patient-assessed measures specific to the assessment of pain, stiffness or fatigue were not identified; where assessed, these domains were largely measured with single-item visual analogue scales.

Reliability

The BASDAI and BASFI have the greatest evidence of reliability (Table 2). Seven instruments have evidence of internal consistency reliability: BASDAI, BASFI, DFI, HAQ-S, RLDQ, ASQoL and AS-AIMS2. Alpha levels for studies evaluating the English BASFI [42], RLDQ [38, 43], ASQoL [39, 43] and a range of instrument translations (for example, the Turkish BASFI [44], Dutch [45] and Finnish versions of the DFI [46]) exceeds 0.90, the criterion recommended for individual patients [4, 9]. Evidence for the BASDAI [42, 43, 47–49] and the Austrian HAQ-S [50] exceed 0.70, the level recommended for groups [4]. Evidence of item-total correlation for the BASDAI, RLDQ and the ASQoL support scale homogeneity [9]. Tests of internal consistency are not appropriate for the instruments that are not based on summated rating scales: Body Chart, BAS-G, PET and PGI.

Ten instruments have evidence of test–retest reliability: BASDAI, Body Chart, ASAQ, BASDAI, DFI, RLDQ, BAS-G, ASQoL, AS-AIMS2 and PGI. All reliability estimates for the RLDQ [38, 43] and the ASQoL [39, 43] exceed criteria necessary for individual assessment. Several reliability estimates for the BASFI [46, 51, 52] and the DFI [5, 45, 46, 53] exceed the criteria necessary for individuals. Most estimates for remaining instruments exceed the criteria necessary for groups [9]. Low levels of test–retest reliability have been reported for the BASDAI (range 0.53–0.64) [54]. The retest period ranged from 1 day to 6 weeks. Few authors indicate if reliability is assessed in patients reporting no change in health over the retest period.

Four instruments have evidence of both forms of reliability—BASDAI, BASFI, DFI and RLDQ—where reliability estimates support application at the group and, in some instances, the individual level. One-week test–retest reliability and associated 95% limits of agreement were calculated for the BASDAI, BASFI, BAS-G and DFI [51]. High reliability estimates were associated with wide score ranges; this was interpreted as indicating poor instrument reliability [51].

Four instruments do not have evidence of reliability in patients with AS: HAQ, AIMS, AIMS2 and PET.

Validity

The ASQoL [39], PET [34] and PGI [36] involved patients in item generation. The BASDAI [28], BASFI [6], RLDQ [38] and AS-AIMS [31] incorporated the opinion of health-care professionals and patients but the role of patients is not made explicit. The DFI included three rheumatologists and the HAQ-S a survey of functional disability in patients with AS. With the exception of the ASAQ [37] and BAS-G [30], for which item generation is not described, the literature and existing instruments provided the major source of items for the remaining instruments.

Evidence supports the internal construct validity of five instruments, the results of which support the single domains of the BASDAI [43, 49], DFI [6], RLDQ [43] and ASQoL [43]. Although the developers of the AS-AIMS2 describe 13 domains, 12 domains were found following principal component analysis [31].

All instruments have evidence for validity through comparison with instruments that measure similar or related constructs, and/or with measures of mobility. This is most extensive for the BASDAI, BASFI and DFI (Table 3). With the exception of the HAQ, AIMS, AS-AIMS2 and PET, all instruments have evidence to support their ability to discriminate between groups of patients with AS defined by clinical, radiographic and socio-demographic variables. This is most extensive for the BASDAI, BASFI and DFI. The BASDAI, BASFI, DFI and HAQ-S have evidence to support their ability to discriminate between groups defined by health service use.

Responsiveness

With the exception of the ASAQ, AIMS2 and AS-AIMS, all instruments have some evidence of responsiveness following completion by patients with AS (Table 3). With the exception of the Body Chart, RLDQ, AIMS, PET and PGI, all instruments have some evidence of responsiveness following both drug therapy and physical therapy. This is most extensive for the BASDAI and BASFI. Effect size statistics were reported for all instruments. Correlation of change scores with change in other variables was reported for the BASDAI, BASFI, DFI, HAQ-S, BAS-G, ASQoL and AIMS. With the exception of the AIMS, Body Chart, RLDQ, PET and PGI, seven instruments had evidence of group discrimination over time. Statistical significance was frequently reported but the clinical significance of score change was rarely addressed. There is limited evidence for the Body Chart, HAQ, HAQ-S, RLDQ and instruments that measure HRQL. Five studies reporting evidence for the HAQ-S describe different stages in a trial of physical therapy [34, 55–58].

Moderate to strong levels of responsiveness were reported for the BASDAI [for example, 49, 59–63] and BASFI (for example, 49, 53, 59–66) following a range of placebo-controlled trials and the longitudinal evaluation of active drugs. Mean score changes greater than 2.0 (scale 0–10) were reported for both the BASDAI and BASFI following the evaluation of anti-TNF therapy with 6- to 52-week follow-up periods.

Few studies reported effect size statistics for the evaluation of instrument responsiveness following physical therapy; most reported mean score change. Moderate and small effect sizes were reported for the BASDAI and BASFI respectively following the longitudinal evaluation of in-patient rehabilitation [67]. Small effect sizes were reported for the BASDAI and BASFI following combined spa and exercise therapy [68, 69]. The BASDAI was responsive to improvement or deterioration in health following the evaluation of usual care [43]. Mean score change for the BASDAI [28, 54, 67–75] and BASFI [5, 54, 67–70, 72–74, 76, 77] did not exceed 1.9 and 1.3 respectively following all physical therapy interventions within a 2- to 40-week follow-up period. BASFI score change of less than 0.7 (scale 0–10) was reported following similar in-patient rehabilitation programmes of 3 weeks' duration [67, 72, 74]; score change of less than 0.6 was reported following a 6-week out-patient exercise programme [78]. Non-statistically significant score change was reported following a long-term, prospective evaluation of function [72, 75].

Moderate to strong levels of responsiveness were reported for the DFI following a range of drug therapy evaluations. Lower levels of responsiveness and poor group discrimination have been reported following physical therapy [5, 67]. There is limited evidence of responsiveness for a modified five-point response scale [54, 68, 74].

The HAQ has limited evidence of responsiveness following drug therapy evaluation in patients with AS but large score changes were reported following the longitudinal evaluation of Infliximab in AS [79]. Evidence suggests that the HAQ-S is not responsive to change in functional ability following physical therapy [34, 55, 58, 68, 80].

Larger score changes have been reported for the single BAS-G items following drug therapy evaluation [79, 82] than following physical therapy [67, 73]. Similarly, the ASQoL was more responsive to change following drug therapy (etanercept) [83, 84] than following physical therapy [68, 69] or usual care [43].

Precision

Floor effects were reported for the HAQ-S (25% scored 0) [56] and RLDQ [43]. Skewed score distributions were also reported for the DFI [16, 85]. Floor effects may be a function of limited item content and/or response options [4], and limit measurement discrimination and responsiveness. Normal score distributions were reported for the ASQoL, BASDAI, BASFI and PGI. Score distributions were not reported for the remaining instruments.

Discussion

To provide the most effective management in the care of individuals with AS it is important to determine how the disease and treatment affect health from the patient's perspective. The application of patient-assessed health instruments has become increasingly important within the assessment of health-care [3, 4] and more specifically within rheumatology [3, 86]. Significant progress in the field has been made since the initial ASAS recommendations, which acknowledged that they could change following new research evidence [7, 8]. This review provides a timely assessment of these recommendations and the first detailed review of AS- and arthritis-specific multi-item, patient-assessed health instruments. The review will inform the appropriate selection of multi-item, patient-assessed health instruments to be used in clinical practice and research.

ASAS recommended five core assessment domains: pain, stiffness, function, global well-being and spinal mobility. From the 15 reviewed multi-item instruments, one assessed pain intensity (Body Chart); five AS-specific instruments (ASAQ, BASFI, DFI, HAQ-S and RLDQ) and one arthritis-specific (HAQ) instrument assessed functional ability; and one instrument assessed global well-being (BAS-G). The BASDAI, an AS-specific measure of disease activity, and three AS-specific measures of HRQL (AS-AIMS2, ASQoL, PGI) include items to assess pain, stiffness and fatigue.

Pain, stiffness and fatigue are frequently described as important symptoms by patients [36, 87] and clinicians [68]. The Body Chart had poor evidence of measurement properties and is not recommended without further evaluation. Although evidence of completion rates were mixed, measurement properties support consideration of the BASDAI as a measure of disease activity. However, other important issues, such as item content and response format, should also be considered.

Six measures of functional ability were reviewed. The ASAQ, HAQ and HAQ-S have limited evidence of measurement properties following completion by patients with AS; the HAQ and HAQ-S also have evidence of poor data quality. The RLDQ has good completion rates and a very high level of reliability, but it is not recommended for application due to poor data quality, the limited range of functional disability assessed, and limited responsiveness.

Both the BASFI and DFI have acceptable levels of reliability. Although both have good evidence for construct validity and similar levels of responsiveness following drug therapy evaluation, the BASFI has better content validity and is more responsive following physical therapy. Further, evidence suggests that the BASFI is more responsive than the DFI in the early stages of treatment with anti-TNF therapies; comparable levels of responsiveness were found after 4 months of treatment [66]. This may be a function of the limited response options for the original DFI. The modified categorical response scale [74, 85] may improve responsiveness. However, patients often experience difficulty in completing VAS, the format of the BASDAI, BASFI and BAS-G, and reservations have been expressed about the interpretation, acceptability and feasibility of VAS scales [4, 9, 54]. Both patients [4, 11, 54] and clinicians [88, 89] have expressed preferences for categorical rating scales. A comparative evaluation of response formats by patients with AS supported a preference for categorical rating scales (49%), followed by numerical rating scales (38%) and visual analogue scales (9%) [54]. The initial ASAS recommendations for functional assessment suggested use of the BASFI or DFI. Evidence suggests that the BASFI and DFI differ quite broadly in terms of item content, response format, levels of patient (and clinician) acceptability and measurement properties in different settings. This suggests that reports of functional ability from these two instruments may not be directly comparable. Further consensus is required to recommend a single instrument for AS-specific functional assessment.

Evidence supports the ASAS recommendation of the BAS-G as a single-item assessment of global well-being [8]. However, single items provide a limited assessment of global health [4]. Since 1999, three AS-specific measures of HRQL have been identified: ASQoL, AS-AIMS2 and PGI. Three arthritis-specific measures of HRQL were also reviewed: AIMS, AIMS2 and PET. These lack evidence of reliability in AS, have limited evidence of validity and cannot be recommended for application in AS assessment without further evaluation. Patients were explicitly involved in item generation for the ASQoL, PET and PGI. Patient participation enhances content validity [4]. Although overlap between ASQoL items and PGI areas was expected, a concurrent evaluation found that several of the areas most frequently nominated by patients completing the PGI (body image, walking and work outside the home) are not addressed by items within the ASQoL [36]. The ASQoL purports to measure AS-related quality of life but does not include some of the 10 most important and frequently mentioned patient concerns [36].

The ASQoL has good completion rates, satisfactory data quality and scaling assumptions, high reliability, some evidence of validity, and good evidence of responsiveness following drug therapy, but small to moderate levels following physical therapy [68]. The ASQoL has a dichotomous response scale which often fails to support sufficiently detailed descriptions of health [4, 90, 91]. The PGI and AS-AIMS2 are two new measures of HRQL. As a result, both have limited evidence for their measurement properties and further evaluation is recommended.

Instrument measurement properties are context-specific attributes that can differ across populations, settings and interventions [21, 22, 91]. ASAS identified three treatment settings: disease-controlling anti-rheumatic therapy (DC-ART), symptom-modifying antirheumatic drugs (SMARDs) and physical therapy, and clinical record keeping [7, 8]. Evidence for measurement and practical properties across these settings should be considered alongside item content and appropriateness to the clinical or research question when selecting an instrument. Although ASAS made several instrument recommendations, the majority of these were for single-item scales which may not provide an adequate assessment of health [4, 9]. Patient-assessed health instruments should provide an accurate assessment of disease impact and health-care from the patient's perspective [3]. The inclusion of multiple items within a questionnaire will provide a more detailed and informative assessment of the health domain or concept [4]. Although quick to complete, single items may be a poor surrogate for a patient's perception of disease impact; content validity is likely to be lower and important information may be lost which hinders data interpretation and usefulness to clinical decision-making [4, 9].

Low levels of test–retest reliability, which did not support application in group assessment, have been reported for a domain-specific, multi-item measure of fatigue [Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory (MFI)] and a single-item VAS for fatigue severity in patients with AS [92]. MFI domains ranged from 0.57 (physical fatigue) to 0.75 (reduced motivation; mental fatigue); fatigue VAS 0.60. Although associated with moderate to good levels of responsiveness, further evaluation of measurement properties is required before either instrument can be recommended for use. Further concurrent evaluations between AS-specific and domain-specific, multi-item, measures of pain, fatigue and stiffness are recommended. Where appropriate, refinement of existing instruments is required before the development of new instruments; seeking the views of people with AS with regard to instrument format, relevance and mode of completion is strongly recommended [9].

Although a range of comparative evaluations exists, further comparative evaluations are required of multi-item AS-specific instruments, such as the modified DFI and BASFI, the newly developed measures of HRQL, and widely-used generic instruments, across different treatment settings. Particular attention should be paid to the evaluation of instrument responsiveness over longer periods, score interpretation and the role of patient-assessed health instruments in clinical decision-making and communicating treatment benefit. Recent quality improvement initiatives within the NHS recognize the importance of evaluating health-care organizations and technologies in terms of patient-assessed outcomes. For instance, the measurement of HRQL is central to the NICE technology appraisal process. With the increasing availability of new and expensive therapies in rheumatology, the challenge to provide more informative, responsive and relevant patient-based assessment of disease impact and treatment efficacy becomes ever more important.

All reviewed studies reported instrument evaluations following completion by groups of patients participating in clinical trials or longitudinal evaluations of care. Although widely accepted in clinical trials [4], there is currently little evidence to support the effectiveness of including patient-assessed health instruments in routine practice and clinical record keeping [93]. Most studies provide group-level estimates of instrument performance and score change, the interpretation of which may be difficult for clinicians wishing to use patient-assessed instruments to inform clinical decision-making at the individual level [21]. Further exploration of the acceptability, feasibility and interpretation of including patient-assessed health instruments in clinical practice and of the benefit to be gained is required.

ASAS improvement criteria, defined as change greater than or equal to 20% (or an absolute score change of 10; scale 0–100) in three of the AS core domains with no worsening in the fourth domain, has been recommended to record the efficacy of SMARD therapy [53]. Relative improvements of 50% (good improvement) or 70% (dramatic improvement), with an absolute improvement of 20 (scale 0–100), have been proposed following treatment with biologics [94]. Improvement criteria have not been recommended following physical therapy or routine practice. Smaller score changes following intensive physical therapy have been reported for the BASDAI and BASFI, with score change not exceeding 19 and 12 respectively (scale 0–100) [69–71]. Several studies reported mean BASFI score change of less than 7 (scale 0–100) [67, 72–74]. Moreover, in contrast to single-item scales, percentage score change in multi-item instruments may be an inappropriate simplification of score change interpretation, providing erroneous indications of treatment effectiveness or instrument responsiveness [95]. It is possible that a 20% score change in the middle of a scale may be quite different to a 20% change at the ends of the scale [22, 95]. Recent applications of item response theory have shown that a number of instruments have items that cluster around the middle of the scale hierarchy [95, 96]. This makes it ‘easier’ for patients scoring in the middle of the scale to register score changes following real changes in health relative to those positioned nearer the ends of the scale [95]. The level of change in health that is important to patients, the minimal clinically important difference (MCID), has not been widely reported and should be addressed in future research. Instruments should be administered longitudinally before and after treatment known to improve HRQL, and health transition questions should be included as external criteria of change [21].

Although generally less responsive than disease-specific instruments [96], generic instruments have been recommended for use alongside disease-specific instruments, and their performance in the assessment of patients with AS should also be considered. The SF-36 [97] is the most widely used generic health profile both generally [3] and in studies of AS patients. The SF-36 is the only generic instrument with evidence of responsiveness following both drug therapy and physical therapy in AS. The physical component summary (PCS) score and associated domains were both responsive [62, 66, 84] and had evidence of discriminative validity [62, 65, 66] following anti-TNF therapies. A concurrent evaluation following anti-TNF therapy reported comparable levels of responsiveness between the SF-36 PCS and physical function domain, the BASFI and patient's global assessment of health [66].

In conclusion, this extensive review provides information necessary for the appropriate selection of AS-specific, multi-item, patient-assessed health instruments. Such instruments, specific to the assessment of pain, stiffness, fatigue or global health, were not identified; where assessed, these domains were largely measured with single-item visual analogue scales. Single items may provide a limited reflection of these important domains. These domains are currently inadequately assessed by AS-specific, multi-item patient-assessed health instruments. The BASDAI has acceptable measurement properties as a measure of disease activity, but there are issues relating to item content and appropriateness of response formats. Although the BASFI and DFI remain the instruments of choice for the assessment of functional disability, consensus is required for the recommendation of a single instrument. The domain of HRQL is important to patients and should also be considered as a core assessment domain.

The authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

The authors thank Dr Krysia Dziedzic, Keele University, and Dr Jonathan Packham, Staffordshire Rheumatology Centre, for their helpful comments on an earlier version of this review. We would also like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments.

References

Russell AS. Ankylosing spondylitis – history. In: Klippel JH, Dieppe PA, eds.

Ward MM. Quality of life in patients with ankylosing spondylitis.

Garratt AM, Schmidt L, Macintosh A, Fitzpatrick R. Quality of life measurement: bibliographic study of patient assessed health outcome measures.

Fitzpatrick R, Davey C, Buxton MJ, Jones DR. Evaluating patient-based outcome measures for use in clinical trials.

Calin A, Garrett S, Whitelock H et al. A new approach to defining functional ability in ankylosing spondylitis: the development of the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis functional index.

Dougados M, Gueguen A, Nakache JP, Nguyen M, Mery C, Amor B. Evaluation of a functional index and an articular index in ankylosing spondylitis.

van der Heijde D, Bellamy N, Calin A, Dougadas M, Khan MA, van der Linden S. Preliminary core sets for endpoints in ankylosing spondylitis.

van der Heijde D, Calin A, Dougadas M, Khan MA, van der Linden S, Bellamy N. Selection of instruments in the core set for DC-ART, SMARD, physical therapy, and clinical record keeping in ankylosing spondylitis. Progress report of the ASAS Working Group. Assessments in Ankylosing Spondylitis.

Streiner DL, Norman GR.

Garratt AM, Schmidt L, Fitzpatrick R. Patient-assessed health outcome measures for diabetes: a structured review.

McDowell I, Newell C.

Bowling A. Measuring disease.

Bowling A. Measuring health.

Bakker C, Boers M, van der Linden S. Measures to assess ankylosing spondylitis: taxonomy, review and recommendations.

Ruof J, Sagha O, Stucki G. Comparative responsiveness of three functional indices in ankylosing spondylitis.

Ruof J, Stucki G. Comparison of the Dougados Functional Index and the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index. A literature review.

Dagfinrud H, Hagen K. Physiotherapy interventions for ankylosing spondylitis.

Dougados M, Dijkmans B, Khan M, Maksymowych W, van der Linden S, Brandt J. Conventional treatments for ankylosing spondylitis.

Braun J, Sieper J, Breban M et al. Anti-tumour necrosis factor alpha therapy for ankylosing spondylitis: international experience.

Bellamy N. Clinimetric concepts in outcome assessment: the OMERACT filter.

Beaton DE, Bombardier C, Katz JN, Wright JG. A taxonomy for responsiveness.

Liang MH, Lew RA, Stucki G, Fortin PR, Daltroy L. Measuring clinically important changes with patient-oriented questionnaires.

Norman GR, Sridhar FG, Guyatt GH, Walter SD. Relation of distribution and anchor-based approaches in interpretation of changes in health-related quality of life.

Haywood KL, Hargreaves J, Lamb SE. Multi-item outcome measures for lateral ligament injury of the ankle: a structured review.

Haywood KL, Garratt AM, Fitzpatrick R. Quality of life in older people: a structured review of generic self-assessed health instruments.

Lee YS, Schlotzhauer T, Ott SM et al. Skeletal status of men with early and late ankylosing spondylitis.

Santos H, Brophy S, Calin A. Exercise in ankylosing spondylitis: how much is optimum?

Garrett S, Jenkinson T, Kennedy G, Whitelock H, Gaisford P, Calin A. A new approach to defining disease status in ankylosing spondylitis: the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis disease activity index.

Dziedzic KSG.

Jones SD, Steiner A, Garrett SL, Calin A. The Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Patient Global Score (BAS-G).

Guillemin F, Challier B, Urlacher F, Vancon G, Pourel J. Quality of life in ankylosing spondylitis: validation of the ankylosing spondylitis Arthritis Impact Measurement Scales 2, a modified Arthritis Impact Measurement Scales Questionnaire.

Daltroy LH, Larson MG, Roberts WN, Liang MH. A modification of the Health Assessment Questionnaire for the spondyloarthropathies.

Bakker C, Hidding A, van der Linden S, van Doorslaer E. Cost effectiveness of group physical therapy compared to individualised therapy for ankylosing spondylitis. A randomised controlled trial.

Bell MJ, Bombardier C, Tugwell P. Measurement of functional status, quality of life, and utility in rheumatoid arthritis.

Haywood KL, Garratt AM, Dziedzic K, Dawes PT. Patient centered assessment of ankylosing spondylitis-specific health related quality of life: evaluation of the Patient Generated Index.

Nemeth R, Smith F, Elswood J, Calin A. Ankylosing spondylitis (AS)—an approach to measurement of severity and outcome: Ankylosing Spondylitis Assessment Questionnaire (ASAQ)—a controlled study.

Abbott CA, Helliwell, PS, Chamberlain MA. Functional assessment in ankylosing spondylitis—Evaluation of a new self-administered questionnaire and correlation with anthropometric variables.

Doward LC, Spoorenberg A, Cook SA et al. Development of the ASQoL: a quality of life instruments specific to ankylosing spondylitis.

Meenan RF, Gertmen PM, Mason JH. Measuring health status in arthritis. The Arthritis Impact Measurement Scales.

Meenan RF, Mason JH, Anderson JJ. AIMS2: the contents and properties of a revised and expanded Arthritis Impacts Measurement Scales health status questionnaire.

Jones SD, Calin A, Steiner A. An update on the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity and functional indices (BASDAI, BASFI): excellent Cronbach's alpha scores [letter].

Haywood KL, Garratt AM, Jordan K, Dziedzic K, Dawes PT. Disease-specific patient-assessed measures of health outcome in ankylosing spondylitis: reliability, validity and responsiveness.

Bostan EE, Borman P, Bodur H, Barca N. Functional disability and quality of life in patients with ankylosing spondylitis.

Creemers MCW, van't Hof MA, Fransse MJAM, van de Putte LBA, Gribnau FWJ, van Riel PLCM. A Dutch version of the Functional Index for Ankylosing Spondylitis: development and validation in a long term study.

Heikkila S, Viitanen JV, Kautianen H et al. Evaluation of the Finnish versions of the functional indices BASFI and DFI in spondylarthropathy.

Claudepierre P, Sibilia J, Goupille P et al. Evaluation of a French version of the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index in patients with spondyloarthropathy.

Claudepierre P, Sibilia J, Roudot-Thoraval F et al. Factors linked to disease activity in a French cohort of patients with spondyloarthropathy.

Calin A, Nakache JP, Guegen A, Zeidler H, Mielants H, Dougadas M. Defining disease activity in ankylosing spondylitis: is a combination of variables (Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index) an appropriate instrument?

Falkenbach A, Franke A, van Tubergen A, van der Linden S. Assessment of functional ability in younger and older patients with ankylosing spondylitis: performance of the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index.

Auleley GR, Benbouazza K, Spoorenberg A et al. Evaluation of the smallest detectable difference in outcome or process variables in ankylosing spondylitis.

Eyres S, Tennant A, Kay L, Waxman R, Helliwell P. Measuring disability in ankylosing spondylitis: comparison of Bath AS Functional Index with Revised Leeds Disability Questionnaire.

Anderson JJ, Baron G, van der Heijde D. Ankylosing spondylitis assessment group preliminary definition of short-term improvement in ankylosing spondylitis.

Van Tubergen A, Debats I, Ryser L et al. Use of a numerical rating scale as an answer modality in ankylosing spondylitis-specific questionnaires.

Hidding A, van der Linden SJ, Boers M et al. Is group physical therapy superior to individualised therapy in ankylosing spondylitis?

Hidding A, van der Linden SJ, Gielen X, de Witte L, Dijkmans B, Moolenburgh M. Continuation of group physical therapy is necessary in ankylosing spondylitis: results of a randomised controlled trial.

Bakker C, Rutten-van-Molken M, Hidding A, van Doorslaer E, Bennett K, van der Linden S. Patient utilities in ankylosing spondylitis and the association with other outcome measures.

Bakker C, van der Linden SJ, van Santen-Hoeufft M, Bolwijn P, Hidding A. Problem elicitation to assess patient priorities in ankylosing spondylitis and fibromyalgia.

Calin A, Nakache JP, Gueguen A, Zeidler H, Mielants H, Dougados M. Outcome variables in ankylosing spondylitis: evaluation of their relevance and discriminant capacity.

Braun J, Brandt J, Listing J et al. Treatment of active ankylosing spondylitis with infliximab: a randomised controlled multicentre trial.

Temekonidis TI, Alamanos Y, Nikas SN. Infliximab therapy in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: an open label 12 month study.

Braun J, Brandt J, Listing J et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of infliximab in the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis. An open, observational, extension study of a three-month, randomised, placebo-controlled trial.

Brandt J, Khariouzou A, Listing J et al. Six-month results of a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of Etanercept treatment in patients with active ankylosing spondylitis.

Dougados M, Behier JM, Jolchine I et al. Efficacy of celecoxib, a cyclooxygenase 2-specific inhibitor, in the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis.

Gorman JD, Sack KE, Davis JC Jr. Treatment of ankylosing spondylitis by inhibition of tumor necrosis factor alpha.

Wanders AJB, Gorman JD, Davis JC, Landewe RBM, van der Heijde DMFM. Responsiveness and discriminative capacity of the assessments in ankylosing spondylitis disease-controlling antirheumatic therapy core set and other outcome measures in a trial of Etanercept in ankylosing spondylitis.

Heikkila S, Viitanen JV, Kautiainen H, Kauppi M. Does improved spinal mobility correlate with functional changes in spondyloarthropathy after short term physical therapy?

van Tubergen A, Landewe R, Heuft-Dorenbosch L et al. Assessment of disability with the World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule II in patients with ankylosing spondylitis.

Van Tubergen A, Landewe R, van der Heijde D et al. Combined spa-exercise therapy is effective in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: a randomized controlled trial.

Band DA, Jones SD, Kennedy LG et al. Which patients with ankylosing spondylitis derive most benefit from an in-patient management program?

Waldner A, Cronstedt H, Stenstrom CH. The Swedish version of the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index. Reliability and validity.

Viitanen JV, Heikkila S. Functional changes in patients with spondylarthropathy. A controlled trial of the effects of short-term rehabilitation and 3-year follow-up.

Sweeney S, Taylor G, Calin A. The effect of a home based exercise intervention package on outcome in ankylosing spondylitis: a randomized controlled trial.

Heikkila S. The Dougados functional index with the 5-point Likert scale is sensitive to change due to intensive physiotherapy and exercise in spondyloarthropathy.

Heikkila S, Viitanen JV, Kautiainen H, Kauppi M. Functional long-term changes in patients with spondylarthropathy.

Cronstedt H, Waldner A, Stenstrom CH. The Swedish version of the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index. Reliability and validity.

Van Tubergen A, Boonen A, Landewe R et al. Cost effectiveness of combined spa-exercise therapy in ankylosing spondylitis: a randomized controlled trial.

Analay Y, Ozcan E, Karan A, Diracoglu D, Aydin R. The effectiveness of intensive group exercise on patients with ankylosing spondylitis.

Stone M, Salonen D, Lax M, Payne U, Lapp V, Inman R. Clinical and imaging correlates of response to treatment with infliximab in patients with ankylosing spondylitis.

Ward MM, Kuzis S. Validity and sensitivity to change of spondylitis-specific measures of functional disability.

Maksymowych WP, Jhangri GS, Leclercq S, Skeith K, Yan A, Russell AS. An open study of pamidronate in the treatment of refractory ankylosing spondylitis.

Maksymowych WP, Jhangri GS, Lambert RG et al. Infliximab in ankylosing spondylitis: a prospective observational inception cohort analysis of efficacy and safety.

Marzo-Ortega H, McGonagle D, O'Connor P, Emery P. Efficacy of etanercept in the treatment of the entheseal pathology in resistant spondylarthropathy: a clinical and magnetic resonance imaging study.

Helliwell PS, Marzo-Ortega H, Tennant A. Comparison of a disease-specific and a generic instrument for measuring health-related quality of life in ankylosing spondylitis.

Spoorenberg A, van der Heijde D, de Klerk E et al. A comparative study of the usefulness of the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index and the Dougados Functional Index in the assessment of ankylosing spondylitis.

Saag KG. OMERACT 6 brings new perspectives to rheumatology measurement research.

Dziedzic K.

Bellamy N, Kaloni S, Pope J, Coulter K, Campbell J. Quantitative rheumatology: a survey of outcome measurement procedures in routine rheumatology outpatient practice in Canada.

Bellamy N, Muirden KD, Brooks PM, Barraclough D, Tellus MM, Campbell J. A survey of outcome measurement procedures in routine rheumatology outpatient practice in Australia.

McHorney CA, Cohen AS. Equating health status measures with item response theory: illustrations with functional status measures.

Terwee CB, Dekker FW, Wiersinga WM, Prummel MF, Bossuyt PMM. On assessing responsiveness of health-related quality of life instruments: guidelines for instrument evaluation.

van Tubergen A, Coenen J, Landewe R et al. Assessment of fatigue in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: a psychometric analysis.

Greenhalgh J, Meadows K. The effectiveness of the use of patient-based measures of health in routine practice in improving the process and outcomes of patient care: a literature review.

Stone MA, Inman RD, Wright JG, Maetzel A. Validation exercise of the Ankylosing Spondylitis Assessment Study (ASAS) Group response criteria in ankylosing spondylitis patients treated with biologics.

Garratt AM in collaboration with the UK Back Pain Exercise and Manipulation Trial. Rasch analysis of the Roland Disability Questionnaire.

Stucki G, Daltroy L, Katz JN, Johannesson M, Liang MH. Interpretation of change scores in ordinal clinical scale and health status measures: the whole may not equal the sum of the parts.

Wiebe S, Guyatt G, Weaver B, Matijevic S, Sidwell C. Comparative responsiveness of generic and specific quality-of-life instruments.

Author notes

Unit of Health-Care Epidemiology, Department of Public Health, University of Oxford, Oxford, 1Staffordshire Rheumatology Centre, University Hospital of North Staffordshire NHS Trust, Stoke-on-Trent, UK and 2Norwegian Centre for Health Services Research, St Olav's Plass, Oslo, Norway.

Comments