-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Annika Kinch Westerdahl, Viveka Frykman, Physicians' knowledge of implantable defibrillator treatment: are we good enough?, EP Europace, Volume 19, Issue 7, July 2017, Pages 1163–1169, https://doi.org/10.1093/europace/euw228

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

When admitted to hospitals, patients with an implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) are treated in a variety of departments. Physicians need to have basic ICD knowledge in order to provide the best possible care from implantation to the end of life. The aim of this study was to assess the levels of knowledge concerning ICD treatment among physicians active in Cardiology, Internal Medicine, and Geriatrics.

This cross-sectional comparative study, after stratified sampling, distributed 432 surveys in 18 hospitals with a response rate of 99.5%. As many as 349 (83%) physicians had experience with ICD patients; 288 (68%) rated their ICD knowledge to be low. According to predefined criteria, 175 (41%) physicians' scores reflected sufficient knowledge. There was a significant difference in the level of knowledge between specialities. Sufficient knowledge was reached by 56 (30%) of the physicians in Internal Medicine and 20 (19%) of them in Geriatrics, whereas in Cardiology 99 (71%) reached sufficient knowledge.

There is lack of basic knowledge in ICD treatment and clinical management among physicians. The majority of the respondents had prior experience in treating ICD patients. Over two-thirds of the physicians rated their knowledge to be low, while test scores revealed sufficient knowledge in only 41% of the physicians surveyed. The lack of ICD knowledge is most prominent in Internal Medicine and Geriatrics, but it also extends to physicians in Cardiology departments. With an increasing number of ICD patients, it is of great importance to fill this knowledge gap as soon as possible.

Introduction

Treatment with implantable cardioverter defibrillators (ICDs) is increasing. Because ICD patients will be treated in all types of departments, physicians need to have sufficient knowledge or access to appropriate expertise to be able to care for this patient group.1

It is projected that an ICD will be indicated for many more patients, mainly due to high incidence of heart failure.2 Experts also highlight that ICD-related problems are increasing and seen in a variety of wards.1 Studies have shown that more than 80% of the ICD patients die in hospitals or healthcare facilities, not at home. Two-thirds of those patients are treated in wards other than Cardiology.3

While an ICD reduces the risk of sudden cardiac death (SCD), painful shocks can occur, especially at the end of life.4 Deactivation of therapy is rarely discussed with the patient.5 Reasons for this are complex, but the lack of knowledge regarding ICD treatment among physicians is a possible reason.6

The aim of this study was to assess the levels of knowledge concerning ICD treatment among physicians active in Cardiology, Internal Medicine, and Geriatrics.

Method

Study design

This cross-sectional comparative study was conducted between 1 March and 31 September 2015. A questionnaire was constructed by using a modified model described by Clark et al.7 The research group consists of two cardiac device specialists with extensive experience and EHRA/IBHRE device certifications and two professors with clinical as well as academic achievements in the field. In addition, a psychologist with expertise in the psychometric field was included. In the early phase of item construction, three focus group meetings with a semi-structured design were held with specialists within Cardiology, Internal Medicine, and Geriatrics. After generating the item pool, items were tested by 10 ICD experts. Some items were dismissed, and some reworded due to potential misinterpretation of content. Later, the instrument underwent a pilot testing at a single institution with physicians within all three specialities. Though minor revisions were made based on the pilot response, most respondents felt that the survey was clearly worded and well designed. The majority, 85%, of the respondents believed that the instrument reliably measured the level of knowledge regarding ICD treatment. The other 15% failed to answer the question. After taking these measures, we considered the instrument to have a good face and content validity consisting of 51 items. It contains 20 items with knowledge-specific questions, 16 questions related to familiarity with international guidelines and 14 descriptive questions. All items have a closed-question structure, wherein items probe knowledge on a ‘true/false’, ‘yes/no’, or a ‘don't know’ response basis. Guideline-specific questions used a four-step Likert scale, ranging from ‘Don't agree’ to ‘Completely agree’ (see Supplementary material online, Appendix S1 for full questionnaire).

Physicians had to state the type of hospital—university or non-university—and in which speciality they were working. Furthermore, in the first part of the questionnaire, the respondent had to specify his or her time since qualification and self-report his or her estimated level of knowledge about ICD treatment.

The investigating group along with 10 clinical ICD experts defined sufficient knowledge in a weighting process. All knowledge-related questions (n = 20) were rated 1–3, where 1 was labelled ‘not so important to know’ and 3 was labelled ‘necessary knowledge’ for physicians' ability to manage patients with ICD. The weighting process resulted in nine questions (see Supplementary material online, Appendix S2) viewed as necessary knowledge. Sufficient knowledge was defined as a basic knowledge regarding ICD purpose and function, in order to avoid exposing patients to unnecessary shock therapy not beneficial to the patients. To achieve sufficient knowledge, it was decided that the respondents had to score 7 of these 9 (78%) necessary knowledge questions. Correct answers were coded as 1, while incorrect answers including the alternative ‘don't know’ were coded as 0. The aggregate scores of all nine items were then summed as a total score.

Study sample and data collection

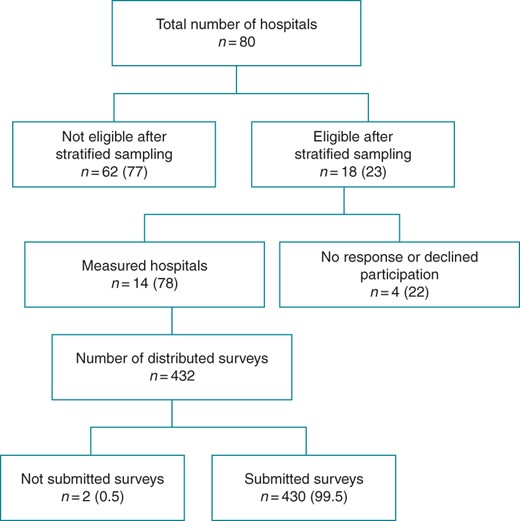

We used a stratified nationwide sampling of hospitals for the distribution of the questionnaire. Cluster sampling was performed, in which hospital size (university or non-university) and geographic spread were taken into account in each sample (Figure 1). Each clinical director gave written consent for the survey to be distributed at his or her clinic. Questionnaires are often associated with low response rates.8 In order to minimize this eventuality, the investigators invited all physicians in targeted departments to participate in a closed meeting in which the survey was distributed and collected manually. Respondents then received, answered, and handed in the survey. Participation in the survey was voluntary, and all respondents were treated anonymously. The study had a very high response rate, but the number of physicians who did not attend the meetings in which the survey was administered is not known. Participants had very little information about the questionnaire's content, and in many cases, the physicians had no information about the distribution of a questionnaire until the meeting started.

Distribution of hospital sampling and questionnaires distribution.

Two previous studies led to the choosing of the specific specialities involved in this study. Cardiology, Internal Medicine, and Geriatrics were the departments that most frequently provided care for ICD patients.3,4

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are presented as means ± standard deviations. Categorical variables are presented as numbers and percentages. Independent t-tests were used to examine differences among physician demographics and levels of knowledge. For between-group comparisons, we employed the Mann–Whitney test for continuous variables. Pearson's χ2 or Fisher's exact tests for smaller sizes were applied to categorical variables. One-way ANOVA was used to compare means between groups. Statistical significance was set at a two-sided P-value of ≤0.05. All results were analysed using SPSS software (Windows Version 22.0).

A statistical power analysis was performed for sample size estimation. It was based on data from the pilot study, which showed a 50% difference in knowledge about ICD treatment between physicians in Cardiology and Internal Medicine departments. With an alpha of 0.05 and a power of 0.80, the projected sample size was estimated to be 93 individuals in each group; with the 3 groups totalling 279 individuals (3 × 93), to be able to show a 20% difference between groups.

Ethics

Approval from the ethical committee was sought; however, because the questionnaire was directed to healthcare professionals only, the committee did not consider an ethical application necessary.

Results

Response rate and self-reported experience with implantable cardioverter defibrillator

A total of 432 surveys were distributed, and 430 were completed and collected. Fourteen out of the 18 (78%) sampled hospitals participated, 5 (36%) of which were university hospitals and 9 (64%) were non-university hospitals. Out of the stratified hospitals, four either did not respond or declined participation in the study. The demographic characteristics of the respondents are given in Table 1.

Baseline characteristics

| . | All (n = 430) . | Cardiology (n = 139) . | Medicine (n = 184) . | Geriatrics (n = 107) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men (n = 428) | 226 (53) | 99 (71) | 93 (51) | 34 (32) |

| Age (n = 417) | 42.9 ± 11.0 | 45.0 ± 10.2 | 41.6 ± 10.5 | 42.3 ± 12.6 |

| Years since graduation (n = 401) | 14.8 ± 11.0 | 17.5 ± 10.3 | 13.1 ± 10.5 | 14.4 ± 12.3 |

| University hospital (n = 430) | 165 (38) | 98 (71) | 51 (28) | 16 (15) |

| Level of education (n = 428) | ||||

| Medical intern | 85 (20) | 16 (12) | 35 (19) | 34 (32) |

| Fellow | 100 (23) | 27 (19) | 55 (30) | 18 (17) |

| Attending physicians | 243 (57) | 96 (69) | 92 (50) | 55 (51) |

| Years as attending physician | 12.9 ± 8.8 | 13.6 ± 8.1 | 12.1 ± 10.0 | 12.9 ± 8.8 |

| Specialist ≥10 years | 142 (58) | 64 (67) | 46 (54) | 32 (58) |

| Self-estimated level of knowledge (n = 422) | ||||

| Low/very low | 288 (68) | 51 (37) | 142 (79) | 95 (90) |

| Good/very good | 134 (32) | 86 (63) | 37 (21) | 11 (10) |

| Experience treating patients with ICD (n = 423) | ||||

| Never | 74 (17) | 5 (4) | 40 (22) | 29 (27) |

| 1–10 times/years | 240 (57) | 52 (37) | 123 (67) | 65 (61) |

| 11–≥21 times/years | 109 (26) | 79 (57) | 20 (11) | 10 (9) |

| Experience treating patients at the end of life (n = 425) | ||||

| Never | 37 (9) | 8 (6) | 21 (11) | 8 (8) |

| 1–10 times/years | 156 (36) | 61 (44) | 63 (34) | 32 (30) |

| 11–≥21 times/years | 232 (54) | 68 (49) | 99 (54) | 65 (61) |

| Number of discussions about ICD deactivation (n = 425) | ||||

| Never | 225 (52) | 36 (26) | 121 (66) | 68 (64) |

| Seldom | 168 (39) | 72 (52) | 61 (33) | 35 (33) |

| Often | 32 (7) | 30 (22) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) |

| Deactivation is ethically permissible (n = 420) | ||||

| Agree completely | 349 (81) | 113 (84) | 153 (80) | 83 (80) |

| Deactivation is legally permissible (n = 420) | ||||

| Agree completely | 385 (90) | 123 (92) | 167 (87) | 95 (91) |

| Patients have the right to refuse treatment/request withdrawal (n = 424) | ||||

| Agree completely | 312 (73) | 100 (75) | 136 (71) | 76 (73) |

| . | All (n = 430) . | Cardiology (n = 139) . | Medicine (n = 184) . | Geriatrics (n = 107) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men (n = 428) | 226 (53) | 99 (71) | 93 (51) | 34 (32) |

| Age (n = 417) | 42.9 ± 11.0 | 45.0 ± 10.2 | 41.6 ± 10.5 | 42.3 ± 12.6 |

| Years since graduation (n = 401) | 14.8 ± 11.0 | 17.5 ± 10.3 | 13.1 ± 10.5 | 14.4 ± 12.3 |

| University hospital (n = 430) | 165 (38) | 98 (71) | 51 (28) | 16 (15) |

| Level of education (n = 428) | ||||

| Medical intern | 85 (20) | 16 (12) | 35 (19) | 34 (32) |

| Fellow | 100 (23) | 27 (19) | 55 (30) | 18 (17) |

| Attending physicians | 243 (57) | 96 (69) | 92 (50) | 55 (51) |

| Years as attending physician | 12.9 ± 8.8 | 13.6 ± 8.1 | 12.1 ± 10.0 | 12.9 ± 8.8 |

| Specialist ≥10 years | 142 (58) | 64 (67) | 46 (54) | 32 (58) |

| Self-estimated level of knowledge (n = 422) | ||||

| Low/very low | 288 (68) | 51 (37) | 142 (79) | 95 (90) |

| Good/very good | 134 (32) | 86 (63) | 37 (21) | 11 (10) |

| Experience treating patients with ICD (n = 423) | ||||

| Never | 74 (17) | 5 (4) | 40 (22) | 29 (27) |

| 1–10 times/years | 240 (57) | 52 (37) | 123 (67) | 65 (61) |

| 11–≥21 times/years | 109 (26) | 79 (57) | 20 (11) | 10 (9) |

| Experience treating patients at the end of life (n = 425) | ||||

| Never | 37 (9) | 8 (6) | 21 (11) | 8 (8) |

| 1–10 times/years | 156 (36) | 61 (44) | 63 (34) | 32 (30) |

| 11–≥21 times/years | 232 (54) | 68 (49) | 99 (54) | 65 (61) |

| Number of discussions about ICD deactivation (n = 425) | ||||

| Never | 225 (52) | 36 (26) | 121 (66) | 68 (64) |

| Seldom | 168 (39) | 72 (52) | 61 (33) | 35 (33) |

| Often | 32 (7) | 30 (22) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) |

| Deactivation is ethically permissible (n = 420) | ||||

| Agree completely | 349 (81) | 113 (84) | 153 (80) | 83 (80) |

| Deactivation is legally permissible (n = 420) | ||||

| Agree completely | 385 (90) | 123 (92) | 167 (87) | 95 (91) |

| Patients have the right to refuse treatment/request withdrawal (n = 424) | ||||

| Agree completely | 312 (73) | 100 (75) | 136 (71) | 76 (73) |

Data given as mean ± SD or n (%).

Total number of responses for each question listed as values n.

ICD, implantable cardioverter defibrillator.

Baseline characteristics

| . | All (n = 430) . | Cardiology (n = 139) . | Medicine (n = 184) . | Geriatrics (n = 107) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men (n = 428) | 226 (53) | 99 (71) | 93 (51) | 34 (32) |

| Age (n = 417) | 42.9 ± 11.0 | 45.0 ± 10.2 | 41.6 ± 10.5 | 42.3 ± 12.6 |

| Years since graduation (n = 401) | 14.8 ± 11.0 | 17.5 ± 10.3 | 13.1 ± 10.5 | 14.4 ± 12.3 |

| University hospital (n = 430) | 165 (38) | 98 (71) | 51 (28) | 16 (15) |

| Level of education (n = 428) | ||||

| Medical intern | 85 (20) | 16 (12) | 35 (19) | 34 (32) |

| Fellow | 100 (23) | 27 (19) | 55 (30) | 18 (17) |

| Attending physicians | 243 (57) | 96 (69) | 92 (50) | 55 (51) |

| Years as attending physician | 12.9 ± 8.8 | 13.6 ± 8.1 | 12.1 ± 10.0 | 12.9 ± 8.8 |

| Specialist ≥10 years | 142 (58) | 64 (67) | 46 (54) | 32 (58) |

| Self-estimated level of knowledge (n = 422) | ||||

| Low/very low | 288 (68) | 51 (37) | 142 (79) | 95 (90) |

| Good/very good | 134 (32) | 86 (63) | 37 (21) | 11 (10) |

| Experience treating patients with ICD (n = 423) | ||||

| Never | 74 (17) | 5 (4) | 40 (22) | 29 (27) |

| 1–10 times/years | 240 (57) | 52 (37) | 123 (67) | 65 (61) |

| 11–≥21 times/years | 109 (26) | 79 (57) | 20 (11) | 10 (9) |

| Experience treating patients at the end of life (n = 425) | ||||

| Never | 37 (9) | 8 (6) | 21 (11) | 8 (8) |

| 1–10 times/years | 156 (36) | 61 (44) | 63 (34) | 32 (30) |

| 11–≥21 times/years | 232 (54) | 68 (49) | 99 (54) | 65 (61) |

| Number of discussions about ICD deactivation (n = 425) | ||||

| Never | 225 (52) | 36 (26) | 121 (66) | 68 (64) |

| Seldom | 168 (39) | 72 (52) | 61 (33) | 35 (33) |

| Often | 32 (7) | 30 (22) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) |

| Deactivation is ethically permissible (n = 420) | ||||

| Agree completely | 349 (81) | 113 (84) | 153 (80) | 83 (80) |

| Deactivation is legally permissible (n = 420) | ||||

| Agree completely | 385 (90) | 123 (92) | 167 (87) | 95 (91) |

| Patients have the right to refuse treatment/request withdrawal (n = 424) | ||||

| Agree completely | 312 (73) | 100 (75) | 136 (71) | 76 (73) |

| . | All (n = 430) . | Cardiology (n = 139) . | Medicine (n = 184) . | Geriatrics (n = 107) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men (n = 428) | 226 (53) | 99 (71) | 93 (51) | 34 (32) |

| Age (n = 417) | 42.9 ± 11.0 | 45.0 ± 10.2 | 41.6 ± 10.5 | 42.3 ± 12.6 |

| Years since graduation (n = 401) | 14.8 ± 11.0 | 17.5 ± 10.3 | 13.1 ± 10.5 | 14.4 ± 12.3 |

| University hospital (n = 430) | 165 (38) | 98 (71) | 51 (28) | 16 (15) |

| Level of education (n = 428) | ||||

| Medical intern | 85 (20) | 16 (12) | 35 (19) | 34 (32) |

| Fellow | 100 (23) | 27 (19) | 55 (30) | 18 (17) |

| Attending physicians | 243 (57) | 96 (69) | 92 (50) | 55 (51) |

| Years as attending physician | 12.9 ± 8.8 | 13.6 ± 8.1 | 12.1 ± 10.0 | 12.9 ± 8.8 |

| Specialist ≥10 years | 142 (58) | 64 (67) | 46 (54) | 32 (58) |

| Self-estimated level of knowledge (n = 422) | ||||

| Low/very low | 288 (68) | 51 (37) | 142 (79) | 95 (90) |

| Good/very good | 134 (32) | 86 (63) | 37 (21) | 11 (10) |

| Experience treating patients with ICD (n = 423) | ||||

| Never | 74 (17) | 5 (4) | 40 (22) | 29 (27) |

| 1–10 times/years | 240 (57) | 52 (37) | 123 (67) | 65 (61) |

| 11–≥21 times/years | 109 (26) | 79 (57) | 20 (11) | 10 (9) |

| Experience treating patients at the end of life (n = 425) | ||||

| Never | 37 (9) | 8 (6) | 21 (11) | 8 (8) |

| 1–10 times/years | 156 (36) | 61 (44) | 63 (34) | 32 (30) |

| 11–≥21 times/years | 232 (54) | 68 (49) | 99 (54) | 65 (61) |

| Number of discussions about ICD deactivation (n = 425) | ||||

| Never | 225 (52) | 36 (26) | 121 (66) | 68 (64) |

| Seldom | 168 (39) | 72 (52) | 61 (33) | 35 (33) |

| Often | 32 (7) | 30 (22) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) |

| Deactivation is ethically permissible (n = 420) | ||||

| Agree completely | 349 (81) | 113 (84) | 153 (80) | 83 (80) |

| Deactivation is legally permissible (n = 420) | ||||

| Agree completely | 385 (90) | 123 (92) | 167 (87) | 95 (91) |

| Patients have the right to refuse treatment/request withdrawal (n = 424) | ||||

| Agree completely | 312 (73) | 100 (75) | 136 (71) | 76 (73) |

Data given as mean ± SD or n (%).

Total number of responses for each question listed as values n.

ICD, implantable cardioverter defibrillator.

Only 2 physicians of those who attended the meetings did not submit the survey after completion, resulting in a response rate of 99.5% (Figure 1). The internal loss varied between the 9 necessary questions, but it never reached more than 14 (3%) out of 430 surveys, which gave a response rate to each question of 97% or more. Though this indicates some missing data, because of the fact that only a very few data were missing, it was considered to have no effect on the results.9

As many as 349 (83%) of all respondents said that they had experience in treating patients with ICD. A total of 218 (75%) physicians working in Internal Medicine or Geriatrics reported to have experience with ICD patients. The majority, 288 (68%), of all physicians including 51 (37%) working in Cardiology departments estimated their level of knowledge to be low or very low. Only 19 (20%) qualified specialists in Cardiology departments estimated their level of knowledge to be very good. For further details, see Table 1.

Sufficient knowledge

There was a significant difference in the level of knowledge between specialities. Only 41% of all physicians reached a sufficient level of knowledge according to the predefined criteria. The level of sufficient knowledge is presented in Table 2.

Sufficient knowledge between medical specialities (correct answer in seven out of the nine necessary questions)

| Question . | All (n = 430) . | Cardiology (n = 139) . | Medicine (n = 184) . | Geriatrics (n = 107) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. An implantable defibrillator primarily helps patients to counteract sudden death (True) (n = 425) | 382 (90) | 131 (94) | 165 (90) | 86 (80) |

| 2. The pacing function will be temporarily deactivated by placing a magnet over an ICD (False) (n = 426) | 150 (35) | 84 (60) | 45 (25) | 21 (19) |

| 3. Shocks can be temporarily deactivated by placing a magnet over an ICD (True) (n = 426) | 292 (69) | 121 (87) | 109 (59) | 62 (58) |

| 4. Shock treatment from an ICD is painful for a conscious patient (True) (n = 426) | 324 (76) | 125 (90) | 127 (69) | 72 (67) |

| 5. It is dangerous for another person to be in physical contact with a patient receiving ICD shocks (False) (n = 421) | 342 (81) | 127 (91) | 145 (79) | 70 (65) |

| 6. Due to safety precautions, it is not possible to deactivate the ICD shock treatment (False) (n = 422) | 304 (72) | 118 (85) | 122 (66) | 64 (60) |

| 7. If ICD shock therapy is deactivated, the pacemaker function in the device will also be deactivated (False) (n = 423) | 287 (68) | 121 (87) | 113 (61) | 53 (50) |

| 8. If ICD shock therapy is deactivated, shocks cannot be activated again (False) (n = 423) | 318 (75) | 124 (89) | 138 (75) | 56 (52) |

| 9. I may externally defibrillate a pulseless ICD patient (True) (n = 416) | 293 (70) | 113 (81) | 126 (69) | 54 (51) |

| Sufficient knowledge (n = 428) | 175 (41) | 99 (71) | 56 (30) | 20 (19) |

| Question . | All (n = 430) . | Cardiology (n = 139) . | Medicine (n = 184) . | Geriatrics (n = 107) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. An implantable defibrillator primarily helps patients to counteract sudden death (True) (n = 425) | 382 (90) | 131 (94) | 165 (90) | 86 (80) |

| 2. The pacing function will be temporarily deactivated by placing a magnet over an ICD (False) (n = 426) | 150 (35) | 84 (60) | 45 (25) | 21 (19) |

| 3. Shocks can be temporarily deactivated by placing a magnet over an ICD (True) (n = 426) | 292 (69) | 121 (87) | 109 (59) | 62 (58) |

| 4. Shock treatment from an ICD is painful for a conscious patient (True) (n = 426) | 324 (76) | 125 (90) | 127 (69) | 72 (67) |

| 5. It is dangerous for another person to be in physical contact with a patient receiving ICD shocks (False) (n = 421) | 342 (81) | 127 (91) | 145 (79) | 70 (65) |

| 6. Due to safety precautions, it is not possible to deactivate the ICD shock treatment (False) (n = 422) | 304 (72) | 118 (85) | 122 (66) | 64 (60) |

| 7. If ICD shock therapy is deactivated, the pacemaker function in the device will also be deactivated (False) (n = 423) | 287 (68) | 121 (87) | 113 (61) | 53 (50) |

| 8. If ICD shock therapy is deactivated, shocks cannot be activated again (False) (n = 423) | 318 (75) | 124 (89) | 138 (75) | 56 (52) |

| 9. I may externally defibrillate a pulseless ICD patient (True) (n = 416) | 293 (70) | 113 (81) | 126 (69) | 54 (51) |

| Sufficient knowledge (n = 428) | 175 (41) | 99 (71) | 56 (30) | 20 (19) |

Data given as n (%).

Total number of responses for each question listed as values n.

Correct answer for each question listed within parentheses.

ICD, implantable cardioverter defibrillator.

Sufficient knowledge between medical specialities (correct answer in seven out of the nine necessary questions)

| Question . | All (n = 430) . | Cardiology (n = 139) . | Medicine (n = 184) . | Geriatrics (n = 107) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. An implantable defibrillator primarily helps patients to counteract sudden death (True) (n = 425) | 382 (90) | 131 (94) | 165 (90) | 86 (80) |

| 2. The pacing function will be temporarily deactivated by placing a magnet over an ICD (False) (n = 426) | 150 (35) | 84 (60) | 45 (25) | 21 (19) |

| 3. Shocks can be temporarily deactivated by placing a magnet over an ICD (True) (n = 426) | 292 (69) | 121 (87) | 109 (59) | 62 (58) |

| 4. Shock treatment from an ICD is painful for a conscious patient (True) (n = 426) | 324 (76) | 125 (90) | 127 (69) | 72 (67) |

| 5. It is dangerous for another person to be in physical contact with a patient receiving ICD shocks (False) (n = 421) | 342 (81) | 127 (91) | 145 (79) | 70 (65) |

| 6. Due to safety precautions, it is not possible to deactivate the ICD shock treatment (False) (n = 422) | 304 (72) | 118 (85) | 122 (66) | 64 (60) |

| 7. If ICD shock therapy is deactivated, the pacemaker function in the device will also be deactivated (False) (n = 423) | 287 (68) | 121 (87) | 113 (61) | 53 (50) |

| 8. If ICD shock therapy is deactivated, shocks cannot be activated again (False) (n = 423) | 318 (75) | 124 (89) | 138 (75) | 56 (52) |

| 9. I may externally defibrillate a pulseless ICD patient (True) (n = 416) | 293 (70) | 113 (81) | 126 (69) | 54 (51) |

| Sufficient knowledge (n = 428) | 175 (41) | 99 (71) | 56 (30) | 20 (19) |

| Question . | All (n = 430) . | Cardiology (n = 139) . | Medicine (n = 184) . | Geriatrics (n = 107) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. An implantable defibrillator primarily helps patients to counteract sudden death (True) (n = 425) | 382 (90) | 131 (94) | 165 (90) | 86 (80) |

| 2. The pacing function will be temporarily deactivated by placing a magnet over an ICD (False) (n = 426) | 150 (35) | 84 (60) | 45 (25) | 21 (19) |

| 3. Shocks can be temporarily deactivated by placing a magnet over an ICD (True) (n = 426) | 292 (69) | 121 (87) | 109 (59) | 62 (58) |

| 4. Shock treatment from an ICD is painful for a conscious patient (True) (n = 426) | 324 (76) | 125 (90) | 127 (69) | 72 (67) |

| 5. It is dangerous for another person to be in physical contact with a patient receiving ICD shocks (False) (n = 421) | 342 (81) | 127 (91) | 145 (79) | 70 (65) |

| 6. Due to safety precautions, it is not possible to deactivate the ICD shock treatment (False) (n = 422) | 304 (72) | 118 (85) | 122 (66) | 64 (60) |

| 7. If ICD shock therapy is deactivated, the pacemaker function in the device will also be deactivated (False) (n = 423) | 287 (68) | 121 (87) | 113 (61) | 53 (50) |

| 8. If ICD shock therapy is deactivated, shocks cannot be activated again (False) (n = 423) | 318 (75) | 124 (89) | 138 (75) | 56 (52) |

| 9. I may externally defibrillate a pulseless ICD patient (True) (n = 416) | 293 (70) | 113 (81) | 126 (69) | 54 (51) |

| Sufficient knowledge (n = 428) | 175 (41) | 99 (71) | 56 (30) | 20 (19) |

Data given as n (%).

Total number of responses for each question listed as values n.

Correct answer for each question listed within parentheses.

ICD, implantable cardioverter defibrillator.

Physicians working in Cardiology departments scored significantly higher than other physicians. On average, doctors in Cardiology had a score of 6.79 ± 1.75 out of 9 possible correct answers, which was significantly 1.56 (P < 0.001) higher than those working within Internal Medicine. The difference was even greater when compared with physicians in Geriatrics; there was a 2.26 (P < 0.001) higher score in favour of those in Cardiology. Also, there was a significant difference of 0.70 (P = 0.006) between Internal Medicine and Geriatrics, with average scores favouring Internal Medicine.

Furthermore, physicians at university hospitals earned higher scores with a mean of 6.23, on average 1.99 (P < 0.001) higher than those who work at non-university hospitals.

Attending physicians in Cardiology earned the best results, with 84 (88%) respondents passing the sufficient level, a significantly better (P < 0.001) result when compared with both all other physicians and fellows and interns within Cardiology. They were also significantly (P < 0.001) better than attending physicians in the other specialities. Furthermore, a significant difference (P = 0.03) was found between attending physicians in Internal Medicine who scored higher than attending physicians in Geriatrics (Table 3).

Mean score (maximum score 9 points) between speciality and level of education

| Speciality/level of education . | Mean score . | Mean difference . | P-value between speciality . | P-value between physicians . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiology (n = 139) | 6.79 ± 1.75 | +1.56 vs. Medicine +2.26 vs. Geriatrics | <0.001 <0.001 | |

| Intern (n = 16) | 4.31 ± 2.21 | −1.39 vs. fellow −3.20 vs. attending | <0.05 <0.001 | |

| Fellow (n = 27) | 5.70 ± 1.88 | −1.81 vs. attending +1.39 vs. intern | <0.001 <0.05 | |

| Attending physician (n = 96) | 7.51 ± 0.91 | +1.81 vs. fellow +3.20 vs. intern | <0.001 <0.001 | |

| Internal Medicine (n = 184)a | 5.24 ± 1.94 | −1.56 vs. Cardiology +0.70 vs. Geriatrics | <0.001 <0.05 | |

| Intern (n = 35) | 4.11 ± 1.88 | −1.27 vs. fellow −1.46 vs. attending | <0.05 <0.001 | |

| Fellow (n = 55) | 5.38 ± 2.04 | −0.19 vs. attending +1.27 vs. intern | N.S. <0.05 | |

| Attending physician (n = 92) | 5.58 ± 1.76 | +0.19 vs. fellow +1.46 vs. intern | N.S. <0.001 | |

| Geriatrics (n = 107) | 4.53 ± 1.89 | −2.26 vs. Cardiology −0.71 vs. Medicine | <0.001 <0.05 | |

| Intern (n = 34) | 3.94 ± 1.46 | −0.61 vs. fellow −0.95 vs. attending | N.S. N.S. | |

| Fellow (n = 18) | 4.56 ± 2.28 | −0.34 vs. attending +0.61 vs. intern | N.S. N.S. | |

| Attending physician (n = 55) | 4.89 ± 1.92 | +0.34 vs. fellow +0.95 vs. intern | N.S. N.S. (0.054) |

| Speciality/level of education . | Mean score . | Mean difference . | P-value between speciality . | P-value between physicians . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiology (n = 139) | 6.79 ± 1.75 | +1.56 vs. Medicine +2.26 vs. Geriatrics | <0.001 <0.001 | |

| Intern (n = 16) | 4.31 ± 2.21 | −1.39 vs. fellow −3.20 vs. attending | <0.05 <0.001 | |

| Fellow (n = 27) | 5.70 ± 1.88 | −1.81 vs. attending +1.39 vs. intern | <0.001 <0.05 | |

| Attending physician (n = 96) | 7.51 ± 0.91 | +1.81 vs. fellow +3.20 vs. intern | <0.001 <0.001 | |

| Internal Medicine (n = 184)a | 5.24 ± 1.94 | −1.56 vs. Cardiology +0.70 vs. Geriatrics | <0.001 <0.05 | |

| Intern (n = 35) | 4.11 ± 1.88 | −1.27 vs. fellow −1.46 vs. attending | <0.05 <0.001 | |

| Fellow (n = 55) | 5.38 ± 2.04 | −0.19 vs. attending +1.27 vs. intern | N.S. <0.05 | |

| Attending physician (n = 92) | 5.58 ± 1.76 | +0.19 vs. fellow +1.46 vs. intern | N.S. <0.001 | |

| Geriatrics (n = 107) | 4.53 ± 1.89 | −2.26 vs. Cardiology −0.71 vs. Medicine | <0.001 <0.05 | |

| Intern (n = 34) | 3.94 ± 1.46 | −0.61 vs. fellow −0.95 vs. attending | N.S. N.S. | |

| Fellow (n = 18) | 4.56 ± 2.28 | −0.34 vs. attending +0.61 vs. intern | N.S. N.S. | |

| Attending physician (n = 55) | 4.89 ± 1.92 | +0.34 vs. fellow +0.95 vs. intern | N.S. N.S. (0.054) |

Number listed as mean ± SD or n.

aTwo physicians within Internal Medicine did not specify their level of education and have not been included in this table.

P-values from ANOVA with Tukey's post hoc test.

Mean score (maximum score 9 points) between speciality and level of education

| Speciality/level of education . | Mean score . | Mean difference . | P-value between speciality . | P-value between physicians . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiology (n = 139) | 6.79 ± 1.75 | +1.56 vs. Medicine +2.26 vs. Geriatrics | <0.001 <0.001 | |

| Intern (n = 16) | 4.31 ± 2.21 | −1.39 vs. fellow −3.20 vs. attending | <0.05 <0.001 | |

| Fellow (n = 27) | 5.70 ± 1.88 | −1.81 vs. attending +1.39 vs. intern | <0.001 <0.05 | |

| Attending physician (n = 96) | 7.51 ± 0.91 | +1.81 vs. fellow +3.20 vs. intern | <0.001 <0.001 | |

| Internal Medicine (n = 184)a | 5.24 ± 1.94 | −1.56 vs. Cardiology +0.70 vs. Geriatrics | <0.001 <0.05 | |

| Intern (n = 35) | 4.11 ± 1.88 | −1.27 vs. fellow −1.46 vs. attending | <0.05 <0.001 | |

| Fellow (n = 55) | 5.38 ± 2.04 | −0.19 vs. attending +1.27 vs. intern | N.S. <0.05 | |

| Attending physician (n = 92) | 5.58 ± 1.76 | +0.19 vs. fellow +1.46 vs. intern | N.S. <0.001 | |

| Geriatrics (n = 107) | 4.53 ± 1.89 | −2.26 vs. Cardiology −0.71 vs. Medicine | <0.001 <0.05 | |

| Intern (n = 34) | 3.94 ± 1.46 | −0.61 vs. fellow −0.95 vs. attending | N.S. N.S. | |

| Fellow (n = 18) | 4.56 ± 2.28 | −0.34 vs. attending +0.61 vs. intern | N.S. N.S. | |

| Attending physician (n = 55) | 4.89 ± 1.92 | +0.34 vs. fellow +0.95 vs. intern | N.S. N.S. (0.054) |

| Speciality/level of education . | Mean score . | Mean difference . | P-value between speciality . | P-value between physicians . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiology (n = 139) | 6.79 ± 1.75 | +1.56 vs. Medicine +2.26 vs. Geriatrics | <0.001 <0.001 | |

| Intern (n = 16) | 4.31 ± 2.21 | −1.39 vs. fellow −3.20 vs. attending | <0.05 <0.001 | |

| Fellow (n = 27) | 5.70 ± 1.88 | −1.81 vs. attending +1.39 vs. intern | <0.001 <0.05 | |

| Attending physician (n = 96) | 7.51 ± 0.91 | +1.81 vs. fellow +3.20 vs. intern | <0.001 <0.001 | |

| Internal Medicine (n = 184)a | 5.24 ± 1.94 | −1.56 vs. Cardiology +0.70 vs. Geriatrics | <0.001 <0.05 | |

| Intern (n = 35) | 4.11 ± 1.88 | −1.27 vs. fellow −1.46 vs. attending | <0.05 <0.001 | |

| Fellow (n = 55) | 5.38 ± 2.04 | −0.19 vs. attending +1.27 vs. intern | N.S. <0.05 | |

| Attending physician (n = 92) | 5.58 ± 1.76 | +0.19 vs. fellow +1.46 vs. intern | N.S. <0.001 | |

| Geriatrics (n = 107) | 4.53 ± 1.89 | −2.26 vs. Cardiology −0.71 vs. Medicine | <0.001 <0.05 | |

| Intern (n = 34) | 3.94 ± 1.46 | −0.61 vs. fellow −0.95 vs. attending | N.S. N.S. | |

| Fellow (n = 18) | 4.56 ± 2.28 | −0.34 vs. attending +0.61 vs. intern | N.S. N.S. | |

| Attending physician (n = 55) | 4.89 ± 1.92 | +0.34 vs. fellow +0.95 vs. intern | N.S. N.S. (0.054) |

Number listed as mean ± SD or n.

aTwo physicians within Internal Medicine did not specify their level of education and have not been included in this table.

P-values from ANOVA with Tukey's post hoc test.

There were no significant differences in the level of knowledge between specialists with long experience (≥10 years since specialist exam) and those with less experience (<10 years), both in total and in all specialities.

Areas of insufficient knowledge

Implantable cardioverter defibrillator shocks are associated with considerable pain if experienced by a conscious patient. Only 324 (76%) of all physicians agreed with this statement. A total of 127 (69%) physicians in Internal Medicine and 72 (67%) physicians in Geriatrics thought that shock therapy was painful.

One incurs no risk by being in physical contact with a person receiving shock from his/her ICD. This fact was unknown to 37 (24%) of the physicians in Geriatrics (Table 2).

It is important for a physician to be able to manage occurrences of cardiac arrest in patients. Of all doctors surveyed, 172 (40%) said that they did not know how to manage and treat sudden cardiac arrest (SCA) in a patient with an ICD, and 123 (29%) falsely stated that one cannot externally defibrillate a pulseless ICD patient. There were 19 (14%) physicians in Cardiology who did not know how to manage and treat SCA, and 22 (16%) who would not use external defibrillators on an ICD patient with SCA.

Physicians' responses reflected limited knowledge regarding the ICD pacemaker function, particularly in regard to magnet application, an area in which 65% of all physicians thought that the pacing function would be turned off if a magnet was placed over the device. One ICD on the market responds differently to magnet application than others in that it automatically activates shock therapy after 8 h despite a magnet being applied. This was known to 67 (15%) of all respondents and to 33 (24%) of the physicians in Cardiology.

Not all respondents were aware of patients' indisputable right to refuse treatment. Only 312 (73%) of the respondents agreed (‘I agree completely’) that patients have the right to refuse treatment, and 3% disagreed completely with this right (‘I completely disagree’).

When self-reporting their awareness regarding international guidelines, 330 (77%) physicians stated that they had little or no awareness, while 53 (38%) physicians working in Cardiology reported to have little or no awareness of those guidelines.

The internationally accepted abbreviations for implantable defibrillator are ICD and cardiac resynchronization therapy defibrillator (CRT-D). Only 101 (24%) respondents were able to identify both, and 44 (10%) of them failed to identify either one. Half, 71 (51%), of the physicians in Cardiology, 25 (14%) of the physicians in Internal Medicine, and only 6 (6%) of the physicians in Geriatrics could identify both.

According to international guidelines, permanent prohibition of professional driving after ICD implantation is recommended.10 Half, 207 (49%), of the physicians did not know that ICD patients are prohibited from driving commercial vehicles in Sweden.

Discussion

The level of knowledge about ICD treatment is insufficient among physicians caring for ICD patients. Not surprisingly, physicians in Cardiology scored highest on the nine questions predefined as most important, with attending physicians achieving the best results. The final results also reveal limited success even among physicians in Cardiology as 29% of the physicians in Cardiology did not reach a sufficient level of knowledge. These results suggest a need for active measures in Cardiology. However, the most significant knowledge gaps existed among physicians working in Internal Medicine and Geriatrics. In these fields, there was no difference in knowledge between attending physicians and those undergoing specialist training.

Response rate and self-reported experience

The high response rate (99.5%) from physicians who attended the meetings is a major strength of this study. It assures more accurate survey results from the whole group of clinically active physicians.9,11 Earlier studies in the field yield a response rate in the range of 12–89% where a low response rate may implicate a risk of sampling bias.12–15

More than one-third of the physicians working in Cardiology estimated their ICD knowledge to be low or very low, despite almost all of them (94%) reporting to have experience in treating ICD patients on a yearly basis. With 71% reaching sufficient scores on the test, there seems to be both some degree of underestimation of knowledge and a need for further education.

Only 17% of all respondents, including physicians working in Internal Medicine and Geriatrics, had never treated a patient with ICD. This low frequency indicates that ICD patients are common and confirms earlier statements that they are admitted to a variety of wards.1,3 Implantable cardioverter defibrillator knowledge must be widespread, and collaboration between physicians from different specialities must be encouraged in order to improve the capacity to care for the increasing number of ICD patients today and in the future.

Sufficient knowledge

There was a significant difference in levels of knowledge between physicians. Those in Cardiology scored higher than all other physicians. In particular, attending physicians in Cardiology departments scored significantly higher than all other physicians in all departments, including other physicians in Cardiology.

Physicians working in university hospitals earned significantly higher results than those working in non-university hospitals.

Areas of insufficient knowledge

Most patients find ICD shocks frightening and painful.16,17 Though the majority of the physicians did acknowledge this, one-fourth of them did not. The results of this study indicate that one-third (31 vs. 33%) of the physicians in Internal Medicine and Geriatrics do not regard ICD shocks to be painful. This finding supports findings in earlier studies, which highlights the importance of physician education to avoid unnecessary patient discomfort.16,17

Physical contact or performing CPR on a person receiving ICD shock constitutes no risk.1 One-third of the physicians in Geriatrics and one-fifth in Internal Medicine were unaware of these facts. Their unawareness could result in failure to comfort patients for the anxiety created by shocks, and even worse the possibility of not performing adequate CPR on ICD patients due to this misconception.

The need for external defibrillation is uncommon but essential in cases when the ICD is not able to convert the arrhythmia itself. Almost one-third of all physicians were not aware of this, an unawareness that may potentially result in delayed or possibly inadequate treatment for this patient group. A finding that potentially mitigates this risk is that 95% of the attending physicians within Cardiology reported to know how to manage and treat SCA in ICD patients.

Deactivation of shock therapy can be permanently done with a programmer or temporarily with a magnet. This deactivation has no effect on the ICD pacing function. As many as one-third of the surveyed physicians thought that deactivation of shock therapy would also turn off the pacing function. This misunderstanding could result in physicians' resistance to fulfil their patients' wishes to deactivate shock therapy. Likewise, ICD can occasionally be overly sensitive to electromagnetic interference or lead noise (e.g. lead fracture). Temporary reprogramming of the ICD using a magnet can prevent inappropriate shocks. This lack of knowledge may lead to reluctance to use a magnet to perform deactivation of shock therapy not only in pacing-dependent patients but also in all CRT-D patients, thus exposing them to a high risk of shocks at the end of life.

Today, there is also an ICD on the market, which after 8 h will activate shock therapy regardless of magnet application.18 This fact was known to 15% of all respondents and to only 33% of the physicians in Cardiology.

Patients always have the right to refuse treatment and can request withdrawal of ICD treatment at any time.19 The majority (73%) of the respondents agreed with this statement (‘I agree completely’), and only 3% disagreed. Deactivation of therapy when a patient is terminally ill is both ethical and legally permissible.19,20 With respect to ethicality and legal permissibility, 81 and 90% of the respondents agreed completely. The legality of deactivation has been shown to be of greater concern and creates a large ethical dilemma for many physicians.6,21 Many physicians view ICD deactivation differently from withdrawal of other life-sustaining devices.22

Guideline awareness among respondents was low. Overall, 77% of the respondents self-reported little or no knowledge of guidelines, although in Cardiology more than 60% of the physicians said that they had good or very good awareness of the guidelines. This confirms earlier results by McHale et al., who reported that only 62% of the cardiologists and general practitioners who routinely managed patients with heart diseases were familiar with the content of the international ICD guidelines.23 Indications for ICD implantation are either secondary or primary prevention of SCD. Only 44% of all physicians knew both indications, confirming the results from earlier studies and suggesting that this lack of knowledge has not improved over time.13

Many physicians failed to identify CRT-D and ICD, the two abbreviations commonly used for implantable defibrillators in patient medical records. Being unaware of these abbreviations could lead to misconceptions and risk, creating an inability to identify that a patient has a defibrillator implanted. As many as 76% of the respondents could not identify both abbreviations, and 10% of the respondents failed to identify any. Another type of ICD that has recently been made available is called the subcutaneous ICD (S-ICD). This new device is different from a transvenous ICD in both size and placement. It adds to the list of abbreviations with which physicians must be familiar. Possibly it would have been easier if all the abbreviations had been coupled with a varying supplemental abbreviation to indicate specific treatment, for example ICD, ICD-CRT, and ICD-S.

Limitations

The number of physicians who did not attend the meetings in which the survey was administered is not known. In the possibility that physicians deliberately stayed away from the meeting due to prior awareness of the survey's distribution, a source of bias may have been created. Our sample could have an overrepresentation of physicians who are interested in and are concerned about this topic. To minimize this, participants were given very little information about the questionnaire's content, and in many cases, the physicians had no information about the distribution of the questionnaire until the meeting started.

There is always a problem with social desirability and questionnaires, in that the respondent may want to answer questions in a manner that will be viewed favourably by others. Taking this tendency into consideration, most of the questions had a correct answer and most of the survey was designed as a test in which only a few questions asked about personal experience and self-estimation. These features were designed to minimize the effects social desirability may have on respondents.

There is always a risk of guessing when testing a person's knowledge with a written test, especially if the answers are in a ‘yes or no’ format. The test employed a ‘do not know’ answer to counteract this.

This study does not provide any information about the level of ICD knowledge among other healthcare professionals.

Whether our data can be generalized to other countries and healthcare systems can be questioned and is difficult to address.

Conclusion

There is lack of basic knowledge in ICD treatment and clinical management among physicians. The majority of the respondents had prior experience in treating patients with ICD. Over two-thirds of the respondents rated their knowledge to be low, while test scores revealed sufficient knowledge in only 41% of the physicians surveyed. The lack of ICD knowledge is most prominent in Internal Medicine and Geriatrics, but it also extends to physicians in Cardiology departments. With an increasing number of ICD patients, it is of great importance to fill this knowledge gap as soon as possible.

Clinical importance

The increasing number of ICD patients will make it impossible for device specialists to follow all patients at all times. This development is shifting some of the responsibility of ICD patient care (i.e. end of life questions) to other specialities and primary care physicians. A basic knowledge about implantable devices is essential for healthcare professionals. The results from this study indicate a need for increased knowledge about ICD treatment, to increase information regarding specific ICD-related questions, and to improve communication between specialists.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at Europace online.

Funding

This study was supported by the Department of Cardiology at Danderyd Hospital and Karolinska Institute Department of Clinical Science, Danderyd Hospital.

Conflict of interest: A.K.W. has received lecture fees from Biotronik, St. Jude Medical. V.F. has received lecture fees from MSD and Boehringer Ingelheim, and she has also conducted studies in collaboration with Medtronic and St. Jude Medical.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all physicians in all hospitals who contributed to this study by answering surveys. Also, we would like to thank the Arrhythmia Clinic in Danderyd Hospital for contributing with their expertise, and Fred Saboonchi and Anne-Cathrine Mattiasson for their contribution in the survey construction. We would like to thank Mårten Rosenqvist for his contribution to the manuscript.