-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Thomas F. Lüscher, Slayman Obeid, From Eisenhower’s heart attack to modern management: a true success story!, European Heart Journal, Volume 38, Issue 41, 01 November 2017, Pages 3066–3069, https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehx569

Close - Share Icon Share

This editorial refers to ‘Improved outcomes in patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction during the last 20 years are related to implementation of evidence-based treatments: experiences from the SWEDEHEART registry 1995–2014’†, by K. Szummer et al., on page 3056.

It was on 23 September 1955 when the President of the USA Dwight D. Eisenhower took a day off and was playing golf at Cherry Hills Country Club. During the game, Ike, as the Americans called him, complained of what he considered to be indigestion.1 The President’s personal physician, Dr Howard Snyder, took the symptoms for a gastrointestinal problem and waited 10 h before referring Eisenhower to a hospital. In the medical history of the President, Dr Snyder noted that he gave Eisenhower amyl nitrate for the chest pain and morphine against pain. Thanks to a solid dose of morphine, Eisenhower fell into a deep sleep and did not wake until the next morning. His angina, however, persisted and finally an electrocardiograph (ECG) was organized from another hospital—today considered a necessity that should be available within minutes of symptom onset.2 The ECG recorded an anterolateral acute myocardial infarction with ST-segment elevations. Only at this point, i.e. >24 h after his symptom onset, was Eisenhower hospitalized.

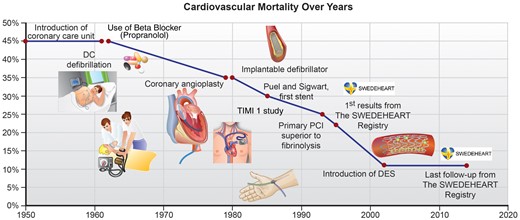

Wall Street reacted in panic and shares plummeted; eventually, the Dow Jones had lost 6% or US$14 billon—and for good reasons: at that time the mortality of an acute myocardial infarction was huge, probably between 30% and 40%, even for those who were able to reach a hospital; indeed, more than half of them died or ended up in severe heart failure with a grim midterm outlook.

Indeed, in the 1950s, not many diagnostic tools or any effective therapy were available.3 Although the clinical presentation of an acute myocardial infarction was known to most clinicians, not many were aware of the variety of symptoms with which an infarction may present. Indeed, in Eisenhower’s case, the initial presentation was atypical. Furthermore, an ECG was not commonly available, cardiac enzymes had not been introduced as diagnostic tests, nor was echocardiography or coronary angiography at hand for emergency physicians or cardiologists. Also, the treatment of acute myocardial infarction was really only ‘tender loving care’, i.e. nitroglycerin and morphine for pain relief. Defibrillation was only introduced by Paul M. Zoll in his seminal paper ‘Determination of ventricular fibrillation by externally applied electric countershock’ in the New England Journal of Medicine a year later4 and implemented into coronary care units in the early 1960s by Bernard Lown.5

Aspirin was well known and used by many, ever since Felix Hoffmann had produced it at Bayer Chemicals in Germany in 1897, but it was exclusively used for pain and fever.6 Only when Sir John Vane showed in 1971 that aspirin also inhibits platelet aggregation7 was it considered years later for patients with acute myocardial infarction. Also, in Eisenhower’s time, beta-blockers had not yet been developed; Sir James Black who won the Nobel Prize in 1988 for his discovery of propranolol8 had not even started his research at ICI laboratories. Finally, Akiro Endo’s work in the 1970s led to the discovery of statins,9 i.e. HMG-coenzyme A reductase inhibitors that were proven to be effective in such patients almost 20 years later in 1992 when the 4S trial was published.10 Lastly, it took several decades until inhibitors of the P2Y12 receptor such as ticlopidine, clopidogrel, prasugrel, or even ticagrelor were introduced into clinical practice.11

The most important step, however, was timely and effective revascularization. Although streptokinase and later tissue plasminogen activators provided some benefit, it required a bold step by a pioneer of cardiology12 to make this more effective: indeed, 40 years ago, i.e. on 16 September 1977,13 Andreas R. Grüntzig at the University Hospital in Zurich performed his seminal procedure in a patient with a proximal stenosis of the left anterior descending coronary artery with his self-made balloon. Although he opened the door to interventional cardiology, it took more than two decades until balloon angioplasty started to be used to treat patients with acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction or STEMI.14 Later, the introduction of stents improved the results of primary percutaneous coronary angioplasty and made it the first-line therapy in this patient population and later also in those with non-STEMI.15 , 16 As a result of all these remarkable developments, the mortality of acute myocardial infarction declined stepwise, but eventually dramatically over the past decade (Figure 1).

In this issue of the journal, Szummer et al. provide numbers for this impressive success story by reporting the outcome of 105 674 patients with STEMI from the SWEDEHEART registry that recruited patients over 20 years.17 The SWEDEHEART registry is particularly remarkable as—in contrast to most other registries—it reports the results of every single patient managed within the Swedish healthcare system, thus avoiding any recruitment bias; this registry really reflects real-world practice. In their quest to identify the impact of changes of treatment on outcomes in this population, the authors compared standard of care, be it medical, reperfusion, or primary percutaneous therapy, at 2-year intervals between 1995 and 2014 as regards 1-year cardiovascular and all-cause mortality.

Of note, this study elegantly depicts an impressive reduction of both 1-year cardiovascular and all-cause mortality after STEMI from 20.1% and 22.1% in the years 1995 and 1996 to 11.6% and 14.1% in the years 2013 and 2014, respectively. This translated into a statistically highly significant reduction in the incidence of mortality between STEMI patients treated in the years 2013 and 2014 compared with those managed in 1995 and 1996 when compared with an age- and gender-matched population with a standardized incidence ratio of 3.74 and 5.54, respectively.

Interestingly, in spite of the results being occasionally concordant with previously published data18 regarding temporal improvement in outcome after STEMI, there remain inconsistences with previously published reports regarding lower in-hospital mortality.19 However, the authors sought to substantiate their findings by reporting significant trends towards optimized medical therapy along with reperfusion therapy and the utilization of primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). As the SWEDEHEART registry enrolled all patients with myocardial infarction in Sweden, this truly reflects temporal trends without biases inherent to most other registries.

Nowadays, thanks to the accumulated evidence and the Guidelines recommending their use, a significantly larger number of patients are on beta-blockers, ACE inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers, statins, and dual antiplatelet therapy compared with the early 1990s, which could partly explain this remarkable improvement in cardiovascular mortality.

As regards the use of beta-blockers in STEMI patients, the most recent 2017 ESC STEMI guidelines2 , 20 no longer provide a clear-cut recommendation beyond those patients with reduced ejection fraction of <40%, although there are several studies demonstrating a reduction in major cardiovascular events and in some studies even mortality, particularly with early application, but they may increase the risk of hypotension and shock.21–23 On the other hand, more robust data are in favour of administering ACE inhibitors particularly in STEMI patients with evidence of heart failure, left ventricular systolic dysfunction, diabetes, or an anterior infarction.2 However, when it comes to medical therapy, perhaps the most substantial evidence in risk reduction and secondary prevention is that provided by the use of statins,24 which is strongly advocated in all patients including those with non-STEMIs16 and unstable angina at high dosages.25 , 26 It is hoped that with the introduction of proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) inhibitors, very low LDL-cholesterol levels can be achieved in high risk patients, allowing for a further decrease of secondary events after myocardial infarction.27 , 28

A significant part of the survival benefit in STEMI patients must be attributed to the increased application of primary PCI over the years, a well-established reperfusion technique, advocated by multiple international guidelines20 as the standard of care in patients with this presentation. Indeed, in a meta-analysis comparing fibrinolytic therapy with primary PCI, early presenters exhibited an improved short-term survival, with death occurring in only 9% and 7%, respectively,29 a benefit which persisted at 5 years of follow-up.14 Accordingly, in the SWEDEHEART registry, the use of primary PCI increased over the years from 5% to 78%, while there was no evidence for an improvement in delays from symptom onset to reperfusion. Thus, the management of myocardial infarction is among the most impressive success stories of evidence-based medicine. Indeed, it highlights the effectiveness of the combined application of effective medical and catheter-based interventions to decrease the incidence of cardiovascular mortality during and after infarction from >40% in the early 1950s to <10% today.

However, a very important question still remains to be answered: what is the next frontier? Certainly, we are in real need of improving outcome further, particularly in an important subset of patients, i.e. those presenting with cardiogenic shock or after sudden cardiac death. Indeed, mortality remains extremely high, in the range of 40–60% at 1 year,30 while stable and conscious patients with infarction who did not require any resuscitation enjoy a survival rate of up to 98% in hospital and 90% at 1 year. What would be required to reduce mortality in this patient population? First of all, more effective cardio-pulmonary resuscitation on site by lay persons and rescue workers to reduce early injuries to the myocardium, circulation, and the brain is needed. Secondly, the door-to-balloon time should be shortened further by fast tracks in the hospitals. Thirdly, the use of percutaneous pumps may be more effective to overcome the acute haemodynamic problems rather than the commonly used catecholamines. Fourthly, novel anti-inflammatory strategies,31 as recently documented in the CANTOS Trial,32 might help to reduce infarct size and facilitate haemodynamic recovery. Finally, there is still hope that stem cell therapies might assist in regenerating the heart muscle after an infarction in the future.33–35

Conflict of interest: none declared.

References

Author notes

The opinions expressed in this article are not necessarily those of the Editors of the European Heart Journal or of the European Society of Cardiology.

doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx515.