-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Rikke Sørensen, Berit Jamie Nielsen, Jannik Langtved Pallisgaard, Christina Ji-Young Lee, Christian Torp-Pedersen, Adherence with oral anticoagulation in non-valvular atrial fibrillation: a comparison of vitamin K antagonists and non-vitamin K antagonists, European Heart Journal - Cardiovascular Pharmacotherapy, Volume 3, Issue 3, July 2017, Pages 151–156, https://doi.org/10.1093/ehjcvp/pvw048

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

The purpose of this study was to describe adherence with non-vitamin K antagonists (NOACs) and vitamin K antagonists (VKA) in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation (NVAF).

By linkage of Danish nationwide registers, we identified patients with NVAF who claimed a prescription of a NOAC (dabigatran, rivaroxaban, and apixaban), or a VKA. Adherence was evaluated according to Proportions of Days Covered, refill gaps, and switch in treatment. Adjusted analyses were calculated with logistic regression and Cox proportional hazard models. Between 2011 and 2014, 46 675 patients with NVAF claimed a prescription of anticoagulation (OAC): 57.3% used VKA, 29.8% dabigatran, 8.5% rivaroxaban, and 4.4% apixaban. During the first 180 days, PDC >80% was the highest among users of rivaroxaban. Compared with rivaroxaban, OR was 0.79 with apixaban (95% CI 0.69–0.92), 0.72 with dabigatran (95% CI 0.66–0.80), and 0.76 with VKAs (95% CI 0.69–0.83). HR for refill gaps between 7 and 89 days of length were (rivaroxaban as reference): apixaban 1.52(95% CI 1.36–1.69), dabigatran 1.72 (95% CI 1.60–1.85), and VKA 2.36(95% CI 2.20–2.52). Refill gaps of more than 89 days occurred in 11.5% of VKA recipients, with substantially lower rates for patients treated with NOAC. Switch between OACs was the highest in users of dabigatran (21.0%) and the lowest in users of apixaban (8.6%).

Among NVAF patients treated with OAC, 42.7% received a NOAC. PDC > 80%, and periods without refill gaps were the highest among users of rivaroxaban. Refill gaps occurred most often with VKA, switch was most common with dabigatran use.

Introduction

Oral anticoagulation (OAC) is recommended for most patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation (NVAF) to prevent serious thromboembolic complications such as stroke.1 Until recently, the main drug of choice has been a vitamin K antagonist (VKA), but use of non-vitamin-K oral anticoagulant (NOAC) drugs has increased since their approval in 2011–12.1–5 NOACs have an advantage over treatment with VKAs due to the lower frequency of interactions with food and other medications, and no need for continuous monitoring of treatment effect (International Normalized Ratio, INR). NOAC treatment has been shown to be non-inferior (and in some cases superior) for preventing thromboembolic events compared with VKA treatment in patients with NVAF, and most importantly NOACs have been associated with a lower risk of intracerebral bleeding compared with the use of VKAs.6–8

However, NOACs have a shorter half-life than VKAs. For dabigatran and apixaban, dosing twice daily is necessary whereas rivaroxaban is recommended once daily.6–8 At the moment, it is not possible to routinely measure availability of the active drug, and protection against thrombosis in patients with poor adherence is largely unknown, but is presumed to be reduced compared with patients with good adherence.3,9 Phase III studies have reported yearly discontinuation rates of up to 14.1%. Until now, real-life studies of treatment adherence have been in populations using one NOAC, but knowledge of comparable adherence rates in patients treated with different NOACs is sparse. The purpose of this study is to describe use and adherence with NOAC therapy in an unselected nationwide cohort of patients with NVAF, as understanding these patterns will contribute to improving responsible use, and eventually ensure better thrombotic protection in individual patients.10

Methods

In Denmark, all residents are covered by a public health care system that pays the majority of expenses related to health care, including outpatient clinics and hospital admissions. Drug expenses are partially reimbursed, and all claimed prescriptions are registered. Data for this study were obtained from the following nationwide registers and linked on an individual level: the Danish National Patient Register, which holds information of all admittances to Danish hospital and outpatient clinics; the Danish Register of Medicinal Product Statistics (the Prescription Register), which holds information of all claimed prescriptions from Danish pharmacies; and the Danish Civil Registration System, which has updated information of vital status of all citizens.

Population

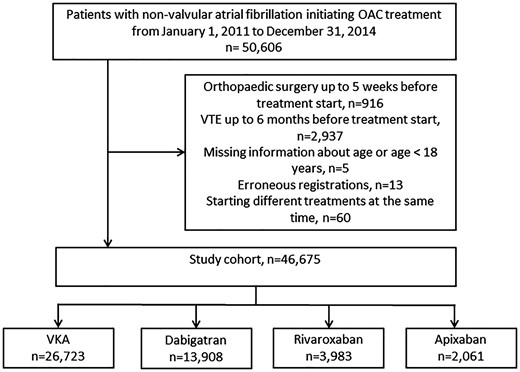

We included all patients above the age of 17 years, with a diagnosis of NVAF (during hospital admission or at an outpatient clinic) who subsequently claimed a prescription for OAC treatment. Patients who received any OAC treatment in the 2 years prior to NVAF diagnosis and subsequent OAC treatment were excluded. The study period was from 2011 to 2014, with a minimum of 1-year follow-up. NVAF was defined as a first-time diagnosis of ICD-10 I48 without heart valve disease or prosthetic heart valves. A flowchart of the population is presented in Figure 1.

Oral anticoagulation treatment

We identified all prescriptions for a VKA (ATC: B01AA03 and B01AA04), dabigatran (ATC: B01AE07), rivaroxaban (ATC: B01AF01), and apixaban (ATC: B01AF02). The Register of Medicinal Products Statistics includes the strength of tablets and the number dispensed. We used this information to calculate treatment periods as previously described.11,12 Since all calculations were time to event only, prior prescriptions were used to calculate dose and treatment period in order to avoid conditioning on the future.

Endpoints

The following endpoints were defined prior to analysis: (1) adherence as OAC coverage determined by claimed prescriptions during the first year of observation. Adherence was calculated as Proportion of Days Covered (PDC). Good adherence was defined as PDC >80%, a cut off that is supported by the International Society for Pharmaceutical and Outcomes Research.13 (2) Refill gap between 7 and 89 days of length illustrating a transient break of therapy. (3) Refill gap ≥ 90 days of length illustrating a period of discontinuation. (4) Switch defined as change from initial OAC to another. Initiation date of a new drug was the date where a prescription of the new drug was claimed.

Statistics

Descriptive analysis of the data was performed using summary statistics for categorical and quantitative (continuous) data. Continuous data was described as medians with interquartile range or means with standard deviation. Frequency tables were generated for categorical data. Endpoints (refill gaps and switch) are presented as percentages and cumulative incidences at predefined times. Multivariable analyses of endpoints (refill gaps and switch) were conducted and adjusted for demographics (age and sex), comorbidities (prior stroke, heart failure, diabetes mellitus, liver disease, prior bleeding, hypertension, ischemic heart disease, peripheral arterial disease, any cancer, chronic kidney disease, hyperthyroidism, and hypothyroidism), prior surgery (percutaneous coronary intervention, CABG), and concomitant medication (verapamil, amiodarone, acetylsalicylic acid, digoxin, antiplatelet agents, and NSAIDs). Exposure to OAC was included as a time-dependent variable, so that the individual only was considered at risk in the individual OAC groups when exposed to the given OAC. Adherence was calculated as PDC, where information of number of tablets available for each patient was obtained from the prescriptions. Standard doses were set for dabigatran (110 mg or 150 mg b.i.d.), rivaroxaban (15 or 20 mg), and apixaban (2.5 or 5 mg b.i.d.). Dose for VKA treatment was calculated individually as done previously.14 The analysis of adherence (PDC > 80%) was performed using logistic regression, adjusted for covariates, and estimated at day 180. Only patients with at least 180 days follow-up were included in this analysis, PDC was calculated as coverage during the period Day 0–180.

Sensitivity analyses were performed with propensity score matching. All covariates in Table 1 were used to calculate the probability of receiving rivaroxaban prior to matching. The following comparisons were made: apixaban and rivaroxaban, dabigatran and rivaroxaban, and warfarin and rivaroxaban. Cox proportional hazards were applied for the sensitivity analyses of refill gaps and switch. Logistic regression was used for the sensitivity analyses of adherence (PDC >80%).

Baseline characteristics

| . | Variable . | VKA (n=26 723) . | Dabigatran (n=13 908) . | Rivaroxaban (n=3983) . | Apixaban (n=2061) . | Total (n=46 675) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | Sex, men, n (%) | 16 033 (60.0) | 7882 (56.7) | 2015 (50.6) | 1201 (58.3) | 27 131 (58.1) |

| Age, years, n (%) 18–64 | 5732 (21.4) | 3142 (22.6) | 515 (12.9) | 391 (19.0) | 9780 (21.0) | |

| 65–74 | 9071 (33.9) | 4912 (35.3) | 1241 (31.2) | 910 (44.2) | 16 134 (34.6) | |

| 75–79 | 4502 (16.8) | 2145 (15.4) | 626 (15.7) | 403 (19.6) | 7676 (16.4) | |

| >79 | 7418 (27.8) | 3709 (26.7) | 1601 (40.2) | 357 (17.3) | 13 085 (28.0) | |

| Comorbidities | Stroke, n (%) | 6114 (22.9) | 3249 (23.4) | 1194 (30.0) | 590 (28.6) | 11 147 (23.9) |

| Ischemic heart disease, n (%) | 8746 (32.7) | 3786 (27.2) | 1252 (31.4) | 556 (27.0) | 14 340 (30.7) | |

| Peripheral artery disease | 3666 (13.7) | 1626 (11.7) | 601 (15.1) | 242 (11.7) | 6135 (13.1) | |

| Heart failure, n (%) | 7154 (26.8) | 3052 (21.9) | 1022 (25.7) | 418 (20.3) | 11 646 (25.0) | |

| Any cancer, n (%) | 5682 (21.3) | 2743 (19.7) | 922 (23.1) | 419 (20.3) | 9766 (20.9) | |

| Chronic kidney disease, n (%) | 4125 (15.4) | 1549 (11.1) | 632 (15.9) | 249 (12.1) | 6555 (14.0) | |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 3872 (14.5) | 1640 (11.8) | 530 (13.3) | 293 (14.2) | 6335 (13.6) | |

| Liver disease, n (%) | 3141 (11.8) | 1438 (10.3) | 517 (13.0) | 215 (10.4) | 5311 (11.4) | |

| Prior bleeding, n (%) | 5398 (20.2) | 2598 (18.7) | 892 (22.4) | 404 (19.6) | 9292 (19.9) | |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 13 279 (49.7) | 6280 (45.2) | 1910 (48.0) | 917 (44.5) | 22 386 (48.0) | |

| COPD, n (%) | 5354 (20.0) | 2493 (17.9) | 922 (23.1) | 354 (17.2) | 9123 (19.5) | |

| Procedures | PCI, n (%) | 4056 (15.2) | 1795 (12.9) | 575 (14.4) | 253 (12.3) | 6679 (14.3) |

| CABG, n (%) | 2958 (11.1) | 1372 (9.9) | 439 (11.0) | 215 (10.4) | 4984 (10.7) | |

| Concominant drugs | NSAID, n (%) | 3575 (13.4) | 1954 (14.0) | 528 (13.3) | 305 (14.8) | 6362 (13.6) |

| ADP inhibitor, n (%) | 1976 (7.4) | 1076 (7.7) | 393 (9.9) | 195 (9.5) | 3640 (7.8) | |

| Heparin, n (%) | 173 (0.6) | 47 (0.3) | 20 (0.5) | 5 (0.2) | 245 (0.5) | |

| Aspirin, n (%) | 11 089 (41.5) | 5464 (39.3) | 1765 (44.3) | 767 (37.2) | 19 085 (40.9) | |

| Persantin, n (%) | 859 (3.2) | 368 (2.6) | 121 (3.0) | 54 (2.6) | 1402 (3.0) | |

| Loop diuretic, n (%) | 6290 (23.5) | 2314 (16.6) | 940 (23.6) | 282 (13.7) | 9826 (21.1) | |

| Verapamil, n (%) | 1277 (4.8) | 517 (3.7) | 148 (3.7) | 66 (3.2) | 2008 (4.3) | |

| Amiodaron, n (%) | 594 (2.2) | 186 (1.3) | 86 (2.2) | 30 (1.5) | 896 (1.9) | |

| No flecainid, n (%) | 26 723 (100.0) | 13 908 (100.0) | 3983 (100.0) | 2061 (100.0) | 46 675 (100.0) | |

| Digoxin, n (%) | 3633 (13.6) | 1405 (10.1) | 542 (13.6) | 159 (7.7) | 5739 (12.3) | |

| Scores | CHADS2, n (%) 0 | 5228 (19.6) | 3170 (22.8) | 646 (16.2) | 500 (24.3) | 9544 (20.4) |

| 1 | 7472 (28.0) | 4185 (30.1) | 1052 (26.4) | 542 (26.3) | 13 251 (28.4) | |

| 2 | 6466 (24.2) | 3036 (21.8) | 894 (22.4) | 435 (21.1) | 10 831 (23.2) | |

| 3 | 3763 (14.1) | 1705 (12.3) | 630 (15.8) | 282 (13.7) | 6380 (13.7) | |

| >3 | 3794 (14.2) | 1812 (13.0) | 761 (19.1) | 302 (14.7) | 6669 (14.3) | |

| CHA2DS2VASc, n (%) 0 | 1727 (6.5) | 974 (7.0) | 116 (2.9) | 120 (5.8) | 2937 (6.3) | |

| 1 | 3346 (12.5) | 2041 (14.7) | 444 (11.1) | 322 (15.6) | 6153 (13.2) | |

| 2 | 5354 (20.0) | 3052 (21.9) | 713 (17.9) | 425 (20.6) | 9544 (20.4) | |

| 3 | 5711 (21.4) | 2827 (20.3) | 808 (20.3) | 420 (20.4) | 9766 (20.9) | |

| 4 | 4389 (16.4) | 2128 (15.3) | 705 (17.7) | 321 (15.6) | 7543 (16.2) | |

| >4 | 6196 (23.2) | 2886 (20.8) | 1197 (30.1) | 453 (22.0) | 10 732 (23.0) | |

| HASBLED, n (%) 0 | 1963 (7.3) | 1146 (8.2) | 136 (3.4) | 161 (7.8) | 3406 (7.3) | |

| 1 | 5486 (20.5) | 3134 (22.5) | 721 (18.1) | 431 (20.9) | 9772 (20.9) | |

| 2 | 7394 (27.7) | 4063 (29.2) | 1126 (28.3) | 560 (27.2) | 13 143 (28.2) | |

| 3 | 6262 (23.4) | 3001 (21.6) | 1013 (25.4) | 477 (23.1) | 10 753 (23.0) | |

| >3 | 5618 (21.0) | 2564 (18.4) | 987 (24.8) | 432 (21.0) | 9601 (20.6) |

| . | Variable . | VKA (n=26 723) . | Dabigatran (n=13 908) . | Rivaroxaban (n=3983) . | Apixaban (n=2061) . | Total (n=46 675) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | Sex, men, n (%) | 16 033 (60.0) | 7882 (56.7) | 2015 (50.6) | 1201 (58.3) | 27 131 (58.1) |

| Age, years, n (%) 18–64 | 5732 (21.4) | 3142 (22.6) | 515 (12.9) | 391 (19.0) | 9780 (21.0) | |

| 65–74 | 9071 (33.9) | 4912 (35.3) | 1241 (31.2) | 910 (44.2) | 16 134 (34.6) | |

| 75–79 | 4502 (16.8) | 2145 (15.4) | 626 (15.7) | 403 (19.6) | 7676 (16.4) | |

| >79 | 7418 (27.8) | 3709 (26.7) | 1601 (40.2) | 357 (17.3) | 13 085 (28.0) | |

| Comorbidities | Stroke, n (%) | 6114 (22.9) | 3249 (23.4) | 1194 (30.0) | 590 (28.6) | 11 147 (23.9) |

| Ischemic heart disease, n (%) | 8746 (32.7) | 3786 (27.2) | 1252 (31.4) | 556 (27.0) | 14 340 (30.7) | |

| Peripheral artery disease | 3666 (13.7) | 1626 (11.7) | 601 (15.1) | 242 (11.7) | 6135 (13.1) | |

| Heart failure, n (%) | 7154 (26.8) | 3052 (21.9) | 1022 (25.7) | 418 (20.3) | 11 646 (25.0) | |

| Any cancer, n (%) | 5682 (21.3) | 2743 (19.7) | 922 (23.1) | 419 (20.3) | 9766 (20.9) | |

| Chronic kidney disease, n (%) | 4125 (15.4) | 1549 (11.1) | 632 (15.9) | 249 (12.1) | 6555 (14.0) | |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 3872 (14.5) | 1640 (11.8) | 530 (13.3) | 293 (14.2) | 6335 (13.6) | |

| Liver disease, n (%) | 3141 (11.8) | 1438 (10.3) | 517 (13.0) | 215 (10.4) | 5311 (11.4) | |

| Prior bleeding, n (%) | 5398 (20.2) | 2598 (18.7) | 892 (22.4) | 404 (19.6) | 9292 (19.9) | |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 13 279 (49.7) | 6280 (45.2) | 1910 (48.0) | 917 (44.5) | 22 386 (48.0) | |

| COPD, n (%) | 5354 (20.0) | 2493 (17.9) | 922 (23.1) | 354 (17.2) | 9123 (19.5) | |

| Procedures | PCI, n (%) | 4056 (15.2) | 1795 (12.9) | 575 (14.4) | 253 (12.3) | 6679 (14.3) |

| CABG, n (%) | 2958 (11.1) | 1372 (9.9) | 439 (11.0) | 215 (10.4) | 4984 (10.7) | |

| Concominant drugs | NSAID, n (%) | 3575 (13.4) | 1954 (14.0) | 528 (13.3) | 305 (14.8) | 6362 (13.6) |

| ADP inhibitor, n (%) | 1976 (7.4) | 1076 (7.7) | 393 (9.9) | 195 (9.5) | 3640 (7.8) | |

| Heparin, n (%) | 173 (0.6) | 47 (0.3) | 20 (0.5) | 5 (0.2) | 245 (0.5) | |

| Aspirin, n (%) | 11 089 (41.5) | 5464 (39.3) | 1765 (44.3) | 767 (37.2) | 19 085 (40.9) | |

| Persantin, n (%) | 859 (3.2) | 368 (2.6) | 121 (3.0) | 54 (2.6) | 1402 (3.0) | |

| Loop diuretic, n (%) | 6290 (23.5) | 2314 (16.6) | 940 (23.6) | 282 (13.7) | 9826 (21.1) | |

| Verapamil, n (%) | 1277 (4.8) | 517 (3.7) | 148 (3.7) | 66 (3.2) | 2008 (4.3) | |

| Amiodaron, n (%) | 594 (2.2) | 186 (1.3) | 86 (2.2) | 30 (1.5) | 896 (1.9) | |

| No flecainid, n (%) | 26 723 (100.0) | 13 908 (100.0) | 3983 (100.0) | 2061 (100.0) | 46 675 (100.0) | |

| Digoxin, n (%) | 3633 (13.6) | 1405 (10.1) | 542 (13.6) | 159 (7.7) | 5739 (12.3) | |

| Scores | CHADS2, n (%) 0 | 5228 (19.6) | 3170 (22.8) | 646 (16.2) | 500 (24.3) | 9544 (20.4) |

| 1 | 7472 (28.0) | 4185 (30.1) | 1052 (26.4) | 542 (26.3) | 13 251 (28.4) | |

| 2 | 6466 (24.2) | 3036 (21.8) | 894 (22.4) | 435 (21.1) | 10 831 (23.2) | |

| 3 | 3763 (14.1) | 1705 (12.3) | 630 (15.8) | 282 (13.7) | 6380 (13.7) | |

| >3 | 3794 (14.2) | 1812 (13.0) | 761 (19.1) | 302 (14.7) | 6669 (14.3) | |

| CHA2DS2VASc, n (%) 0 | 1727 (6.5) | 974 (7.0) | 116 (2.9) | 120 (5.8) | 2937 (6.3) | |

| 1 | 3346 (12.5) | 2041 (14.7) | 444 (11.1) | 322 (15.6) | 6153 (13.2) | |

| 2 | 5354 (20.0) | 3052 (21.9) | 713 (17.9) | 425 (20.6) | 9544 (20.4) | |

| 3 | 5711 (21.4) | 2827 (20.3) | 808 (20.3) | 420 (20.4) | 9766 (20.9) | |

| 4 | 4389 (16.4) | 2128 (15.3) | 705 (17.7) | 321 (15.6) | 7543 (16.2) | |

| >4 | 6196 (23.2) | 2886 (20.8) | 1197 (30.1) | 453 (22.0) | 10 732 (23.0) | |

| HASBLED, n (%) 0 | 1963 (7.3) | 1146 (8.2) | 136 (3.4) | 161 (7.8) | 3406 (7.3) | |

| 1 | 5486 (20.5) | 3134 (22.5) | 721 (18.1) | 431 (20.9) | 9772 (20.9) | |

| 2 | 7394 (27.7) | 4063 (29.2) | 1126 (28.3) | 560 (27.2) | 13 143 (28.2) | |

| 3 | 6262 (23.4) | 3001 (21.6) | 1013 (25.4) | 477 (23.1) | 10 753 (23.0) | |

| >3 | 5618 (21.0) | 2564 (18.4) | 987 (24.8) | 432 (21.0) | 9601 (20.6) |

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; CABG, coronary artery bypass surgery; NSAID, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; VKA, vitamin K antagonist.

Baseline characteristics

| . | Variable . | VKA (n=26 723) . | Dabigatran (n=13 908) . | Rivaroxaban (n=3983) . | Apixaban (n=2061) . | Total (n=46 675) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | Sex, men, n (%) | 16 033 (60.0) | 7882 (56.7) | 2015 (50.6) | 1201 (58.3) | 27 131 (58.1) |

| Age, years, n (%) 18–64 | 5732 (21.4) | 3142 (22.6) | 515 (12.9) | 391 (19.0) | 9780 (21.0) | |

| 65–74 | 9071 (33.9) | 4912 (35.3) | 1241 (31.2) | 910 (44.2) | 16 134 (34.6) | |

| 75–79 | 4502 (16.8) | 2145 (15.4) | 626 (15.7) | 403 (19.6) | 7676 (16.4) | |

| >79 | 7418 (27.8) | 3709 (26.7) | 1601 (40.2) | 357 (17.3) | 13 085 (28.0) | |

| Comorbidities | Stroke, n (%) | 6114 (22.9) | 3249 (23.4) | 1194 (30.0) | 590 (28.6) | 11 147 (23.9) |

| Ischemic heart disease, n (%) | 8746 (32.7) | 3786 (27.2) | 1252 (31.4) | 556 (27.0) | 14 340 (30.7) | |

| Peripheral artery disease | 3666 (13.7) | 1626 (11.7) | 601 (15.1) | 242 (11.7) | 6135 (13.1) | |

| Heart failure, n (%) | 7154 (26.8) | 3052 (21.9) | 1022 (25.7) | 418 (20.3) | 11 646 (25.0) | |

| Any cancer, n (%) | 5682 (21.3) | 2743 (19.7) | 922 (23.1) | 419 (20.3) | 9766 (20.9) | |

| Chronic kidney disease, n (%) | 4125 (15.4) | 1549 (11.1) | 632 (15.9) | 249 (12.1) | 6555 (14.0) | |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 3872 (14.5) | 1640 (11.8) | 530 (13.3) | 293 (14.2) | 6335 (13.6) | |

| Liver disease, n (%) | 3141 (11.8) | 1438 (10.3) | 517 (13.0) | 215 (10.4) | 5311 (11.4) | |

| Prior bleeding, n (%) | 5398 (20.2) | 2598 (18.7) | 892 (22.4) | 404 (19.6) | 9292 (19.9) | |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 13 279 (49.7) | 6280 (45.2) | 1910 (48.0) | 917 (44.5) | 22 386 (48.0) | |

| COPD, n (%) | 5354 (20.0) | 2493 (17.9) | 922 (23.1) | 354 (17.2) | 9123 (19.5) | |

| Procedures | PCI, n (%) | 4056 (15.2) | 1795 (12.9) | 575 (14.4) | 253 (12.3) | 6679 (14.3) |

| CABG, n (%) | 2958 (11.1) | 1372 (9.9) | 439 (11.0) | 215 (10.4) | 4984 (10.7) | |

| Concominant drugs | NSAID, n (%) | 3575 (13.4) | 1954 (14.0) | 528 (13.3) | 305 (14.8) | 6362 (13.6) |

| ADP inhibitor, n (%) | 1976 (7.4) | 1076 (7.7) | 393 (9.9) | 195 (9.5) | 3640 (7.8) | |

| Heparin, n (%) | 173 (0.6) | 47 (0.3) | 20 (0.5) | 5 (0.2) | 245 (0.5) | |

| Aspirin, n (%) | 11 089 (41.5) | 5464 (39.3) | 1765 (44.3) | 767 (37.2) | 19 085 (40.9) | |

| Persantin, n (%) | 859 (3.2) | 368 (2.6) | 121 (3.0) | 54 (2.6) | 1402 (3.0) | |

| Loop diuretic, n (%) | 6290 (23.5) | 2314 (16.6) | 940 (23.6) | 282 (13.7) | 9826 (21.1) | |

| Verapamil, n (%) | 1277 (4.8) | 517 (3.7) | 148 (3.7) | 66 (3.2) | 2008 (4.3) | |

| Amiodaron, n (%) | 594 (2.2) | 186 (1.3) | 86 (2.2) | 30 (1.5) | 896 (1.9) | |

| No flecainid, n (%) | 26 723 (100.0) | 13 908 (100.0) | 3983 (100.0) | 2061 (100.0) | 46 675 (100.0) | |

| Digoxin, n (%) | 3633 (13.6) | 1405 (10.1) | 542 (13.6) | 159 (7.7) | 5739 (12.3) | |

| Scores | CHADS2, n (%) 0 | 5228 (19.6) | 3170 (22.8) | 646 (16.2) | 500 (24.3) | 9544 (20.4) |

| 1 | 7472 (28.0) | 4185 (30.1) | 1052 (26.4) | 542 (26.3) | 13 251 (28.4) | |

| 2 | 6466 (24.2) | 3036 (21.8) | 894 (22.4) | 435 (21.1) | 10 831 (23.2) | |

| 3 | 3763 (14.1) | 1705 (12.3) | 630 (15.8) | 282 (13.7) | 6380 (13.7) | |

| >3 | 3794 (14.2) | 1812 (13.0) | 761 (19.1) | 302 (14.7) | 6669 (14.3) | |

| CHA2DS2VASc, n (%) 0 | 1727 (6.5) | 974 (7.0) | 116 (2.9) | 120 (5.8) | 2937 (6.3) | |

| 1 | 3346 (12.5) | 2041 (14.7) | 444 (11.1) | 322 (15.6) | 6153 (13.2) | |

| 2 | 5354 (20.0) | 3052 (21.9) | 713 (17.9) | 425 (20.6) | 9544 (20.4) | |

| 3 | 5711 (21.4) | 2827 (20.3) | 808 (20.3) | 420 (20.4) | 9766 (20.9) | |

| 4 | 4389 (16.4) | 2128 (15.3) | 705 (17.7) | 321 (15.6) | 7543 (16.2) | |

| >4 | 6196 (23.2) | 2886 (20.8) | 1197 (30.1) | 453 (22.0) | 10 732 (23.0) | |

| HASBLED, n (%) 0 | 1963 (7.3) | 1146 (8.2) | 136 (3.4) | 161 (7.8) | 3406 (7.3) | |

| 1 | 5486 (20.5) | 3134 (22.5) | 721 (18.1) | 431 (20.9) | 9772 (20.9) | |

| 2 | 7394 (27.7) | 4063 (29.2) | 1126 (28.3) | 560 (27.2) | 13 143 (28.2) | |

| 3 | 6262 (23.4) | 3001 (21.6) | 1013 (25.4) | 477 (23.1) | 10 753 (23.0) | |

| >3 | 5618 (21.0) | 2564 (18.4) | 987 (24.8) | 432 (21.0) | 9601 (20.6) |

| . | Variable . | VKA (n=26 723) . | Dabigatran (n=13 908) . | Rivaroxaban (n=3983) . | Apixaban (n=2061) . | Total (n=46 675) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | Sex, men, n (%) | 16 033 (60.0) | 7882 (56.7) | 2015 (50.6) | 1201 (58.3) | 27 131 (58.1) |

| Age, years, n (%) 18–64 | 5732 (21.4) | 3142 (22.6) | 515 (12.9) | 391 (19.0) | 9780 (21.0) | |

| 65–74 | 9071 (33.9) | 4912 (35.3) | 1241 (31.2) | 910 (44.2) | 16 134 (34.6) | |

| 75–79 | 4502 (16.8) | 2145 (15.4) | 626 (15.7) | 403 (19.6) | 7676 (16.4) | |

| >79 | 7418 (27.8) | 3709 (26.7) | 1601 (40.2) | 357 (17.3) | 13 085 (28.0) | |

| Comorbidities | Stroke, n (%) | 6114 (22.9) | 3249 (23.4) | 1194 (30.0) | 590 (28.6) | 11 147 (23.9) |

| Ischemic heart disease, n (%) | 8746 (32.7) | 3786 (27.2) | 1252 (31.4) | 556 (27.0) | 14 340 (30.7) | |

| Peripheral artery disease | 3666 (13.7) | 1626 (11.7) | 601 (15.1) | 242 (11.7) | 6135 (13.1) | |

| Heart failure, n (%) | 7154 (26.8) | 3052 (21.9) | 1022 (25.7) | 418 (20.3) | 11 646 (25.0) | |

| Any cancer, n (%) | 5682 (21.3) | 2743 (19.7) | 922 (23.1) | 419 (20.3) | 9766 (20.9) | |

| Chronic kidney disease, n (%) | 4125 (15.4) | 1549 (11.1) | 632 (15.9) | 249 (12.1) | 6555 (14.0) | |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 3872 (14.5) | 1640 (11.8) | 530 (13.3) | 293 (14.2) | 6335 (13.6) | |

| Liver disease, n (%) | 3141 (11.8) | 1438 (10.3) | 517 (13.0) | 215 (10.4) | 5311 (11.4) | |

| Prior bleeding, n (%) | 5398 (20.2) | 2598 (18.7) | 892 (22.4) | 404 (19.6) | 9292 (19.9) | |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 13 279 (49.7) | 6280 (45.2) | 1910 (48.0) | 917 (44.5) | 22 386 (48.0) | |

| COPD, n (%) | 5354 (20.0) | 2493 (17.9) | 922 (23.1) | 354 (17.2) | 9123 (19.5) | |

| Procedures | PCI, n (%) | 4056 (15.2) | 1795 (12.9) | 575 (14.4) | 253 (12.3) | 6679 (14.3) |

| CABG, n (%) | 2958 (11.1) | 1372 (9.9) | 439 (11.0) | 215 (10.4) | 4984 (10.7) | |

| Concominant drugs | NSAID, n (%) | 3575 (13.4) | 1954 (14.0) | 528 (13.3) | 305 (14.8) | 6362 (13.6) |

| ADP inhibitor, n (%) | 1976 (7.4) | 1076 (7.7) | 393 (9.9) | 195 (9.5) | 3640 (7.8) | |

| Heparin, n (%) | 173 (0.6) | 47 (0.3) | 20 (0.5) | 5 (0.2) | 245 (0.5) | |

| Aspirin, n (%) | 11 089 (41.5) | 5464 (39.3) | 1765 (44.3) | 767 (37.2) | 19 085 (40.9) | |

| Persantin, n (%) | 859 (3.2) | 368 (2.6) | 121 (3.0) | 54 (2.6) | 1402 (3.0) | |

| Loop diuretic, n (%) | 6290 (23.5) | 2314 (16.6) | 940 (23.6) | 282 (13.7) | 9826 (21.1) | |

| Verapamil, n (%) | 1277 (4.8) | 517 (3.7) | 148 (3.7) | 66 (3.2) | 2008 (4.3) | |

| Amiodaron, n (%) | 594 (2.2) | 186 (1.3) | 86 (2.2) | 30 (1.5) | 896 (1.9) | |

| No flecainid, n (%) | 26 723 (100.0) | 13 908 (100.0) | 3983 (100.0) | 2061 (100.0) | 46 675 (100.0) | |

| Digoxin, n (%) | 3633 (13.6) | 1405 (10.1) | 542 (13.6) | 159 (7.7) | 5739 (12.3) | |

| Scores | CHADS2, n (%) 0 | 5228 (19.6) | 3170 (22.8) | 646 (16.2) | 500 (24.3) | 9544 (20.4) |

| 1 | 7472 (28.0) | 4185 (30.1) | 1052 (26.4) | 542 (26.3) | 13 251 (28.4) | |

| 2 | 6466 (24.2) | 3036 (21.8) | 894 (22.4) | 435 (21.1) | 10 831 (23.2) | |

| 3 | 3763 (14.1) | 1705 (12.3) | 630 (15.8) | 282 (13.7) | 6380 (13.7) | |

| >3 | 3794 (14.2) | 1812 (13.0) | 761 (19.1) | 302 (14.7) | 6669 (14.3) | |

| CHA2DS2VASc, n (%) 0 | 1727 (6.5) | 974 (7.0) | 116 (2.9) | 120 (5.8) | 2937 (6.3) | |

| 1 | 3346 (12.5) | 2041 (14.7) | 444 (11.1) | 322 (15.6) | 6153 (13.2) | |

| 2 | 5354 (20.0) | 3052 (21.9) | 713 (17.9) | 425 (20.6) | 9544 (20.4) | |

| 3 | 5711 (21.4) | 2827 (20.3) | 808 (20.3) | 420 (20.4) | 9766 (20.9) | |

| 4 | 4389 (16.4) | 2128 (15.3) | 705 (17.7) | 321 (15.6) | 7543 (16.2) | |

| >4 | 6196 (23.2) | 2886 (20.8) | 1197 (30.1) | 453 (22.0) | 10 732 (23.0) | |

| HASBLED, n (%) 0 | 1963 (7.3) | 1146 (8.2) | 136 (3.4) | 161 (7.8) | 3406 (7.3) | |

| 1 | 5486 (20.5) | 3134 (22.5) | 721 (18.1) | 431 (20.9) | 9772 (20.9) | |

| 2 | 7394 (27.7) | 4063 (29.2) | 1126 (28.3) | 560 (27.2) | 13 143 (28.2) | |

| 3 | 6262 (23.4) | 3001 (21.6) | 1013 (25.4) | 477 (23.1) | 10 753 (23.0) | |

| >3 | 5618 (21.0) | 2564 (18.4) | 987 (24.8) | 432 (21.0) | 9601 (20.6) |

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; CABG, coronary artery bypass surgery; NSAID, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; VKA, vitamin K antagonist.

The multivariable models were tested for the absence of interactions, linearity of continuous variable (Cox proportional hazards model), and proportions of hazards (Cox proportional hazards model), and found to be valid. List of abbreviations is presented in, see Supplementary material online, Appendix, Table 1A.

Results

Between 2011 and 2014, a total of 46 675 patients with NVAF initiated treatment with OAC, of whom 42.7% were treated with a NOAC. Distributions between treatments were: 57.3% VKAs, 29.8% dabigatran, 8.5% rivaroxaban, and 4.4% apixaban. One-fifth of the patients were between 18–64 years of age, 34% were aged 65–74 years, 16.4% 75–79 years, and 28% >79 years. Approximately 40% of the patients had a very high risk of stroke defined as a CHA2DS2VASc score ≥4. The presence of comorbidities such as previous stroke, ischemic heart disease, heart failure, and hypertension were common across the groups, as was the use of concomitant medications as NSAIDs and antiplatelet therapy (primarily acetylsalicylic acid). Baseline characteristics are presented in Table 1.

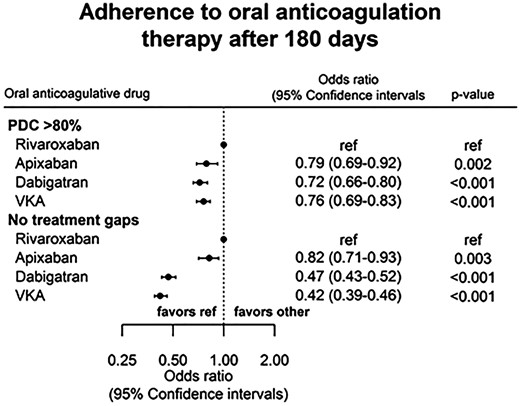

Good adherence defined as PDC > 80%, evaluated after 180 days was highest among users of rivaroxaban. With rivaroxaban as a reference: OR was 0.79 with apixaban (95% CI 0.69–0.92, P 0.002), 0.72 with dabigatran (95% CI 0.66–0.80, P < 0.001), and 0.76 with VKAs (95% CI 0.69–0.83, P <0.001). Likewise the rivaroxaban group had the largest proportion of patients with no refill gaps during the first year, while the VKA group had the lowest. Adjusted odds ratios (OR) for treatment adherence are presented in Figure 2.

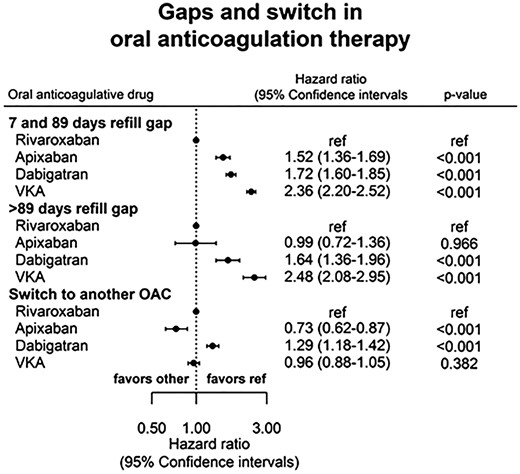

During the study period, the risk of experiencing a gap in prescriptions (of both 7–89 days and ≥90 days) increased with time, as did the risk of switching to a different OAC. Gaps of 7–89 days were very common: HR were (rivaroxaban as reference): apixaban 1.52 (95% CI 1.36–1.69, P < 0.001), dabigatran 1.72 (95% CI 1.60–1.85, P < 0.001), and VKA 2.36 (95% CI 2.20–2.52, P < 0.001). Incidence rates of gaps ≥90 days were low among users of NOACs and much higher for users of VKA (11.5% VKA, 6.1% dabigatran, 3.4% rivaroxaban, and 2.6% apixaban). The risk of switch was the highest among users of dabigatran, followed by VKA and the lowest among users of apixaban. Numbers are presented in Table 2, adjusted HRRs in Figure 3. Baseline characteristics of patients with PDC >80% is presented in, see Supplementary material online, Appendix, Table 2A. Propensity score matching was performed as sensitivity analyses. The results were comparable with the main findings.

Incidence rates gaps and switch

| . | Gaps 7–89 days . | . | Gaps ≥ 90 days . | . | Switch . | . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Events/no. of patients (%) . | Incidence rates per 1000 py . | Events/no. of patients (%) . | Incidence rates per 1000 py . | Events/no. of patients (%) . | Incidence rates per 1000 py . |

| Apixaban | 541/2061 (26.3) | 339.1 | 54/2061 (2.6) | 27.6 | 178/2061 (8.6) | 89.0 |

| Dabigatran | 5191/13 908 (37.3) | 306.3 | 854/13 908 (6.1) | 37.2 | 2922/13 908 (21.0) | 113.1 |

| Rivaroxaban | 897/3983 (22.5) | 199.7 | 136/3983 (3.4) | 25.8 | 532/3983 (13.3) | 91.8 |

| VKA | 14 153/26 723 (53.0) | 424.3 | 3078/26 723 (11.5) | 57.5 | 4499/26 723 (16.8) | 70.0 |

| . | Gaps 7–89 days . | . | Gaps ≥ 90 days . | . | Switch . | . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Events/no. of patients (%) . | Incidence rates per 1000 py . | Events/no. of patients (%) . | Incidence rates per 1000 py . | Events/no. of patients (%) . | Incidence rates per 1000 py . |

| Apixaban | 541/2061 (26.3) | 339.1 | 54/2061 (2.6) | 27.6 | 178/2061 (8.6) | 89.0 |

| Dabigatran | 5191/13 908 (37.3) | 306.3 | 854/13 908 (6.1) | 37.2 | 2922/13 908 (21.0) | 113.1 |

| Rivaroxaban | 897/3983 (22.5) | 199.7 | 136/3983 (3.4) | 25.8 | 532/3983 (13.3) | 91.8 |

| VKA | 14 153/26 723 (53.0) | 424.3 | 3078/26 723 (11.5) | 57.5 | 4499/26 723 (16.8) | 70.0 |

Incidence rates gaps and switch

| . | Gaps 7–89 days . | . | Gaps ≥ 90 days . | . | Switch . | . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Events/no. of patients (%) . | Incidence rates per 1000 py . | Events/no. of patients (%) . | Incidence rates per 1000 py . | Events/no. of patients (%) . | Incidence rates per 1000 py . |

| Apixaban | 541/2061 (26.3) | 339.1 | 54/2061 (2.6) | 27.6 | 178/2061 (8.6) | 89.0 |

| Dabigatran | 5191/13 908 (37.3) | 306.3 | 854/13 908 (6.1) | 37.2 | 2922/13 908 (21.0) | 113.1 |

| Rivaroxaban | 897/3983 (22.5) | 199.7 | 136/3983 (3.4) | 25.8 | 532/3983 (13.3) | 91.8 |

| VKA | 14 153/26 723 (53.0) | 424.3 | 3078/26 723 (11.5) | 57.5 | 4499/26 723 (16.8) | 70.0 |

| . | Gaps 7–89 days . | . | Gaps ≥ 90 days . | . | Switch . | . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Events/no. of patients (%) . | Incidence rates per 1000 py . | Events/no. of patients (%) . | Incidence rates per 1000 py . | Events/no. of patients (%) . | Incidence rates per 1000 py . |

| Apixaban | 541/2061 (26.3) | 339.1 | 54/2061 (2.6) | 27.6 | 178/2061 (8.6) | 89.0 |

| Dabigatran | 5191/13 908 (37.3) | 306.3 | 854/13 908 (6.1) | 37.2 | 2922/13 908 (21.0) | 113.1 |

| Rivaroxaban | 897/3983 (22.5) | 199.7 | 136/3983 (3.4) | 25.8 | 532/3983 (13.3) | 91.8 |

| VKA | 14 153/26 723 (53.0) | 424.3 | 3078/26 723 (11.5) | 57.5 | 4499/26 723 (16.8) | 70.0 |

Discussion

This is one of the first studies to compare adherence with three different NOACs and VKA in a real life population. The main findings were (1) during the first 180 days, PDC > 80% was highest among users of rivaroxaban, followed by users of other NOACs and VKA. (2) Refill gaps between 7 and 89 days were common and were the lowest for users of rivaroxaban. (3) Refill gaps >89 days occurred most commonly among users of VKA, with substantially lower rates for patients treated with NOACs. (4) Incidence of switch between OAC was the highest in users of dabigatran and the lowest among users of apixaban.

A little less than half of the patients were initiated on a NOAC in our real-world study, which confirms the previously seen rapid uptake of NOACs in the general NVAF population.1–4 Patients treated with rivaroxaban in our real-life study had a higher median age compared with those treated with rivaroxaban in the ROCKET AF trial (76 vs. 73 years), whereas median ages among the dabigatran- and apixaban-treated patients were comparable with those in the RE-LY and ARISTOTLE trials, respectively.6–8 Other real-life studies have shown both younger and older populations, which indicate that NOAC treatment is implemented broadly.3,15,16 Numerous studies have analyzed the effect of baseline characteristics as age, gender and comorbidity on adherence rates, but until now the results have been diverse.3,4,17 Thus, it is unclear how different baseline characteristics among the different OAC groups may have affected our results.

Previous epidemiological studies have reported a higher adherence rate among users of dabigatran than VKA, with PDC > 80% over the first year in 76.8% of the patients.17 Comparable rates were found in two other studies of NOACs (one reporting combined data for all three NOACs mixed),16,18 but opposed to one large American study where less than half of the patients had PDC >80% (the lowest among patients receiving VKA).18 One Swedish study compared different NOACs and found higher adherence rates for users of rivaroxaban than dabigatran, but no difference compared with apixaban users.15 In our study, a higher proportion of rivaroxaban users had PDC > 80% than dabigatran, apixaban, and VKA users, but rates were not as high as in the Swedish study.15

Refill gaps were found to be very common, with approximately 25–50% of patients experiencing a gap of 7–89 days during the study period. A similar trend was seen in a survey by European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) where 14.5% of the patients reported that they temporarily discontinued their treatment, and 26.6% had missed medication at least once.19 Our discontinuation rates (refill gap > 90 days) were the highest among VKA users, where 11.5% discontinued treatment during the study period. This is in line with the discontinuation rates seen in the randomized trials, in which 5.1–15.3% of VKA users discontinued treatment after 1 year.6–8 The findings of both shorter and longer interruption of therapy are concerning, since periods without OAC in AF patients are associated with increased risk of stroke, a risk that is accentuated by the number of risk factors.3,5,10,20

Switching between OACs was most common among users of dabigatran, and the proportion increased with study time. This could likely be due to side effects, but the reasons have not been studied in this analysis. Others might propose that dosing twice daily vs. once daily might affect the switch of OAC, but treatment adherence has previously shown to be comparable with both regimens.21

Limitations

One major limitation of this study is inherent in the observational nature of our study, where confounders may have influenced our results. To overcome this challenge, adjusted analyses, including known confounders present in our registries, were performed. Other confounders may still be present, but presumed equally in all OAC groups. In addition, analyses were performed both in all patients and in a propensity-matched cohort, with comparable results.

In our study, the size of treatment groups varied, as >50% of the population used VKA, with declining proportions among each NOACs, with apixaban being the smallest group (4.4%). This can be explained by time of approval, as apixaban was the last NOAC to be approved in Denmark.

Comparison of adherence/persistence between NOACs is straightforward since these agents’ drugs require fixed treatment with one or two tablets daily. Comparisons with VKA carries a risk of bias since the dose may vary widely. We calculated the daily dose based on time between prescriptions and number of tablets dispensed for all drugs, but since the dose calculated is less certain for VKA the calculations of PDC and gaps are less certain in VKA-treated patients.

The Danish healthcare system delivers services to all residents regardless of socioeconomic status and partially reimburses drug expenses. The concordance between drug dispensing and drug consumption is likely to be very high, since reimbursement of drug expenses is only partial.22

The definition of breaks in this study has been redefined to no OAC coverage (refill gap) from 7 to 89 days. This was done to ensure capture of ‘real breaks’, not just missed tablets due to reasonable causes such as occasionally forgetting, delays of prescription claims, and pauses of therapy due to medical examination. The method used for calculation of drug exposure has been used previously.23–25 Good adherence defined as PDC > 80% is generally accepted, but the clinical risk of thrombosis might be increased even using this definition.26

Conclusion

In NVAF patients treated with OAC, 42.7% patients received a NOAC. We found that PDC > 80% and periods without refill gaps were the highest among users of rivaroxaban. Refill gaps were very common and occurred most often in VKA users. The trend is concerning, as poor adherence of OAC for both short- and long-periods leaves the patient at higher risk of thrombosis. We recommend future focus of individual guidance and education to improve adherence in patients treated with both VKA and NOACs.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at European Heart Journal – Cardiovascular Pharmacotherapy online.

Funding

The study was supported by an unrestricted grant by Bayer HealthCare.

Conflict of interest: none declared.