-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Ben Deen, Naomi B. Pitskel, Kevin A. Pelphrey, Three Systems of Insular Functional Connectivity Identified with Cluster Analysis, Cerebral Cortex, Volume 21, Issue 7, July 2011, Pages 1498–1506, https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhq186

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Despite much research on the function of the insular cortex, few studies have investigated functional subdivisions of the insula in humans. The present study used resting-state functional connectivity magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to parcellate the human insular lobe based on clustering of functional connectivity patterns. Connectivity maps were computed for each voxel in the insula based on resting-state functional MRI (fMRI) data and segregated using cluster analysis. We identified 3 insular subregions with distinct patterns of connectivity: a posterior region, functionally connected with primary and secondary somatomotor cortices; a dorsal anterior to middle region, connected with dorsal anterior cingulate cortex, along with other regions of a previously described control network; and a ventral anterior region, primarily connected with pregenual anterior cingulate cortex. Applying these regions to a separate task data set, we found that dorsal and ventral anterior insula responded selectively to disgusting images, while posterior insula did not. These results demonstrate that clustering of connectivity patterns can be used to subdivide cerebral cortex into anatomically and functionally meaningful subregions; the insular regions identified here should be useful in future investigations on the function of the insula.

Introduction

The insula is a functionally and cytoarchitectonically diverse region of cortex, with subregions involved in gustatory and olfactory processing, components of somatosensation, interoception, motivation, and the maintenance of homeostasis (Augustine 1996; Small et al. 1999; Craig 2002, 2009; Olausson et al. 2002). Posterior insula (PI), adjacent to auditory cortex and secondary somatosensory region SII, responds to touch, pain, and thermal stimulation (Craig et al. 2000; Brooks et al. 2002; McGlone et al. 2002; Olausson et al. 2002; Ostrowsky et al. 2002) and is a critical site for interoception (Craig 2002). Anterior insula, continuous with primary gustatory cortex and adjacent to medial temporal olfactory cortex, responds to taste and smell stimuli (Yaxley et al. 1990; Scott et al. 1991; Small et al. 1999; de Araujo et al. 2003) and is involved in the experience of emotions such as disgust (Calder et al. 2000; Adolphs et al. 2003; Wicker et al. 2003). Generally, the insula is a multimodal integration region well-placed to evaluate the emotional or motivational salience of certain stimuli, providing an interface between external information and internal motivational states (Mesulam and Mufson 1982b; Augustine 1996; Craig 2002, 2009; Seeley et al. 2007).

In the macaque, the insula has been subdivided into 3 cytoarchitectonic regions: an agranular region of ventral anterior insula, adjacent to temporal allocortex; a dysgranular region of dorsal anterior to middle insula, adjacent to posterior orbitofrontal cortex; and a granular region of middle to posterior insula (Mesulam and Mufson 1982a). This organization reflects a gradual change in cytoarchitectonic complexity, from allocortex centered on the piriform lobe to isocortex of dorsal posterior insula and beyond (Augustine 1996). Tract-tracing studies show that the insula has reciprocal connections with nearby medial temporal, temporopolar, and orbitofrontal cortex, as well as the cingulate gyrus and lateral prefrontal areas (Mesulam and Mufson 1982b; Mufson and Mesulam 1982). Anterior insula is connected to anterior cingulate gyrus, while posterior insula is also connected with middle cingulate, around supplementary motor area (SMA; Mesulam and Mufson 1982b; Mufson and Mesulam 1982; Vogt and Pandya 1987; Luppino et al. 1993).

Few studies have explicitly investigated subdivisions of the insula in humans. Prior work has detailed the gyri and sulci comprising the insula, using postmortem specimens or MR images (Türe et al. 1999; Naidich et al. 2004). Functionally, several studies have investigated differences in evoked responses to specific tasks across subregions of the insula (e.g., Baliki et al. 2009; Mutschler et al. 2009). Furthermore, Nanetti et al. (2009) provided a connectivity-based parcellation of the left insula into anterior and posterior divisions, using k-means clustering of connectivity patterns derived from diffusion tensor imaging (DTI)-based tractography.

A recent line of work has used patterns of correlations between resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) signals to subdivide functional regions in humans (Cohen et al. 2008; van den Heuvel et al. 2008; Shen et al. 2010). Correlations between low-frequency blood oxygen level–dependent (BOLD) signal variation in distant regions, even in the absence of external stimulation, have been observed in a range of networks and have been used as an assay of functional connectivity in the human brain (Biswal et al. 1995; Lowe et al. 1998; Greicius et al. 2003; Beckmann et al. 2005; Fox et al. 2005). Resting-state BOLD signal correlations are thought to primarily reflect intrinsic neural activity, not evoked by a specific cognitive process; this claim is supported by the finding of intact functional networks in subjects in unconscious states such as sleep, sedation, and even coma (Greicius et al. 2008; Boly et al. 2009; Larson-Prior et al. 2009; Martuzzi et al. 2009).

In particular, the anterior insula/frontal operculum and dorsal anterior cingulate cortex (dACC) form a consistently observed functional network, described as a control network (Dosenbach et al. 2007; Larson-Prior et al. 2009). Seeley et al. (2007) found a similar but broader network, including both ventral and dorsal anterior insula (dAI), and much of anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), including dACC and pregenual anterior cingulate cortex (pACC). Research on whole-brain functional connectivity patterns with seeds in different locations in the insula has also found that posterior insula is primarily connected with middle cingulate and SMA, while anterior insula is connected with a distinct region of dorsal anterior cingulate (Taylor et al. 2009), consistent with anatomical connectivity patterns in the macaque. However, seed-based approaches to the identification of distinct connectivity patterns associated with insular subregions have several important disadvantages to data-driven clustering approaches: 1) the seed-based method may miss connectivity patterns associated with subregions that were not seeded and 2) this method may not capture the full extent of each region of insula with a given pattern of functional connectivity.

In the present study, we subdivided the insula based on whole-brain functional connectivity maps, using a data-driven clustering technique. First, connectivity maps were computed from resting-state data, using seed time courses from each voxel in 2 anatomically defined regions of interest (ROIs) encompassing the left and right insula. Connectivity maps for each voxel, treated as vectors, were then divided into 3 groups using cluster analysis, separately for the left and right insula. Each insular subregion identified with this cluster analysis was then used as a seed region in subsequent whole-brain connectivity analyses to determine the connectivity pattern associated with each subregion. Furthermore, we used these clusters as ROIs in a separate fMRI data set to examine evoked neural responses to disgusting and neutral images. Our approach offers a data-driven method for identifying regions with distinct connectivity patterns, and the results provide an important contribution to the general problem of identifying functional subregions of the insula in humans.

Materials and Methods

Thirty adult subjects (16 male, age 18–31) participated in resting-state scans, and 20 subjects (9 male, age 19–33) participated in the disgusting/neutral image experiment, 4 of whom had also received resting runs. Subjects had no history of neurological or psychiatric impairment. All subjects gave written informed consent, and the protocol was approved by the Human Investigation Committee of the Yale University School of Medicine.

Brain images were acquired on a 3-T Siemens Magnetom Trio scanner. High-resolution T1-weighted structural images of the whole brain were acquired with a 3D MPRAGE sequence. Among the 30 subjects with resting-state scans, 21 subjects were given one pulse sequence (time repetition [TR] = 1900 ms; time echo [TE] = 2.96 ms; flip angle α = 9°; field of view [FOV] = 256 mm; matrix = 2562; slice thickness = 1 mm; 160 slices; number of excitations [NEX] = 1), while the remaining 9 subjects received a slightly different sequence (TR = 1230 ms; TE = 1.73 ms; flip angle α = 9°; FOV = 250 mm; matrix = 2502; slice thickness = 1 mm; 176 slices; NEX = 3). All 20 subjects performing the emotional task received the former pulse sequence. Because anatomical images were used only for coregistration and normalization, this difference did not influence our analyses of the functional data. For all subjects, functional images were acquired using a gradient-recalled echo planar pulse sequence (TR = 2000 ms; TE = 25 ms; flip angle α = 60°; FOV = 220 mm; matrix = 642; slice thickness = 4 mm; 34 slices).

During resting runs, subjects were presented a screen with a gray background and a black crosshair in the center; they were instructed to keep their eyes open, to remain awake, and to stay as still as possible. Resting scans lasted 6:40 or 200 volumes, within a single run.

To elicit responses to disgusting stimuli, we used an emotion regulation task, analogous to the design of Ochsner et al. (2002) but with negative images chosen specifically to evoke disgust. In this task, subjects viewed disgusting or neutral images, taken from the International Affective Picture System (Lang et al. 2008); disgusting pictures included moldy food, humans with unsightly skin conditions, rotten teeth, and so on. The relative number of faces and objects in neutral and disgusting conditions were approximately balanced. While viewing disgusting images, subjects were asked either to passively view the images or to increase or decrease their emotional response to the image using a specified strategy. In the present study, we only investigated evoked responses to passively viewed disgusting and neutral images; the influence of emotion regulation will be presented elsewhere. On each trial, subjects were first presented with instructions for 6 s (either “Look,” “Increase,” or “Decrease,” followed by a specific strategy for increase/decrease trials); the image for 4 s; an affect ranking screen for 6 s, in which subjects were asked to report their emotional response on a Likert scale from neutral (1) to disgusted (5) using a trackball mouse; and a screen reading “Relax” for 2 s. White text and images were presented on a black background. Between trials, subjects viewed a fixation cross for 2–6 s. Each subject received one 407-volume run, with 9 trials of each of 4 conditions (look-neutral, look-disgusting, increase, and decrease), as well as 12 s of fixation at the beginning of the experiment and 10 s at the end. Trials were presented in pseudorandom order, counterbalanced across subjects.

Data were processed using BrainVoyager QX 2.0 (Brain Innovation), along with in-house MATLAB scripts. The first 3 volumes from each resting data set and first 6 volumes from each task data set were removed to allow longitudinal magnetization to reach steady state. Functional data sets were then preprocessed; steps included rigid-body motion correction, slice scan timing correction, linear trend removal, and high pass filtering (3 cycles per series cutoff). Task data were also spatially smoothed using 4 mm–full-width at half-maximum (FWHM) Gaussian kernel. We did not spatially smooth resting-state data to avoid blurring differences in connectivity patterns between neighboring voxels. Instead, resting data were temporally smoothed with a 2.8 s-FWHM Gaussian kernel.

To reduce the influence of variation unrelated to neural activity on connectivity analyses, 9 nuisance variables were removed from resting-state data via linear regression. These included the global mean signal, a time course from white matter, a time course from the left lateral ventricle, and 6 motion parameters. White matter signal was taken from a 3 mm cubic ROI around the Talairach coordinate (−26, −13, 31), and ventricular signal was taken from a 3 mm cube around (−19, −35, 15); we verified that these coordinates fell in white matter and ventricle, respectively, in each subject's normalized anatomical image. We also applied a custom script to remove any pairs of consecutive volumes with an estimated 0.5 mm of translation in any direction or 0.5° of rotation about any axis between them to diminish potential effects of rapid motion occurring within the TR, which in some cases cannot be corrected with rigid-body motion correction. However, no volumes met these criteria.

Functional data were coregistered to high-resolution anatomical images, which were in turn normalized to Talairach space (Talairach and Tournoux 1988). Normalization was performed in 2 steps: images were first aligned with stereotactic axes and then transformed to the Talairach grid using a piecewise affine transformation based on manual identification of the anterior and posterior commissure and the edges of cortex along each axis. Subsequent analyses were performed on preprocessed data in a space of 3-mm resolution aligned with Talairach space.

The left and right insula were defined anatomically by drawing insular gray matter on the Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) 152 standard brain. The limits of the insula were taken to be the anterior, superior, and inferior periinsular sulci (Türe et al. 1999; Naidich et al. 2004). These ROIs were converted to Talairach space by normalizing the MNI brain in the same way that individual subject anatomical images were normalized. The resulting left insula ROI fell within a box bounded by the planes x = −23 and −43, y = −17 and 24, and z = −12 and 20; the right insula ROI was contained within the reflection of this box about the x-axis. Each voxel in the insular ROIs (converted to 3-mm resolution) was used as a seed in a whole-brain functional connectivity analysis: Their resting-state time series were normalized and used as regressors in general linear model (GLM)–based analyses for each subject. Resulting beta maps were averaged across subjects and treated as cross-subject connectivity maps for a given seed region.

We then applied k-means clustering to these subject-averaged beta maps, treated as vectors, using squared Euclidean distance as the distance measure. Clustering was performed separately for the left and right insula. The k-means algorithm was repeated 100 times, and the solution that minimized within-cluster variance was chosen to avoid the influence of random initial cluster membership on our results. We chose to implement the basic k-means algorithm rather than more sophisticated graph-theoretic or spectral techniques (e.g., Meilă and Shi 2000; Shi and Malik 2000; Ng et al. 2002) because the latter are intended for sparse graphs. Insofar, as voxels in the insula have time courses and connectivity maps that are correlated with those of many other voxels within the ROI, this system has a dense distance matrix.

We specified that the analysis find k = 3 clusters; solutions for k = 2 and 4 are presented in the Supplementary Materials, available online. The choice of 3 clusters was initially based on exploratory connectivity analyses with seeds placed in various positions around the insula, which suggested that there were 3 distinct patterns of large-scale connectivity. The primary justification for this choice of k is that when cluster analyses with higher k were performed on our data set, each of the connectivity maps associated with the resulting clusters typically corresponded closely with one of the 3 maps found using k = 3. For an illustration of this, see Supplementary Figure S2, with connectivity maps associated with the k = 4 solution.

We then performed connectivity analyses using the clusters as seeds. Whole-brain voxel-wise regression analyses were performed for each subject, using BOLD signal averaged over each cluster as regressors and combined across subjects in a random-effects analysis. Resulting t-maps were thresholded by controlling the false discovery rate at q < 0.05 using the Simes procedure to correct for multiple comparisons (Genovese et al. 2002). For display, these maps were overlayed on an inflated cortical surface using CARET surface mapping software (http://brainmap.wustl.edu/caret; Van Essen et al. 2001) and the PALS cortical atlas (Van Essen 2005).

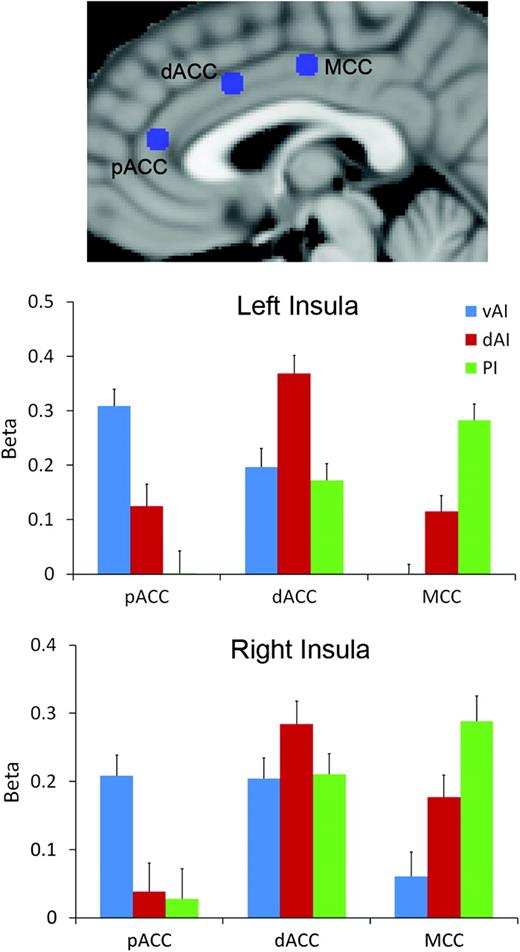

ROI-based analyses were performed to closely examine connectivity between cingulate and insular cortices and to statistically assess regional differences in connectivity strengths. Cingulate ROIs were defined as 9 mm spheres surrounding 3 coordinates placed along the middle to anterior cingulate, identified anatomically using the MNI 152 brain. The coordinates were each separated by 28 mm along the y-axis; their position along the z-axis was chosen such that the spheres fell just below the cingulate sulcus. Coordinates were placed at middle cingulate cortex (MCC, 0, −10, 41), dACC (0, 14, 35), and pACC(0, 38, 17). We assessed connectivity between the 3 cingulate ROIs and 3 insula subregions identified with cluster analysis, by regressing signal from cingulate regions on signal from insula regions (with means removed from all time series). Betas from each regression were statistically assessed with one-sample 2-tailed t-tests. Functional connections of a given cingulate region to different insular regions were statistically compared, using paired 2-sample 2-tailed t-tests. Effects of laterality on connectivity strengths are not investigated in the present study; such differences, if present, could reflect either true differences in connectivity or subtle differences in the extent of insula clusters on the left and right.

Whole-brain GLM-based analyses were also performed on task data. The model contained 7 regressors, modeling responses to the instruction period, affect rating period, and relax period, as well as the image presentation period for each of 4 conditions. Regressors were defined as boxcars peaking during each period, convolved with a double gamma hemodynamic response function. Beta values for regressors from look-neutral and look-disgusting conditions were averaged across insula subregions defined by cluster analysis. Betas for each region and each of 2 conditions were statistically assessed with one-sample 2-tailed t-tests; betas within each region were also compared between conditions (disgusting vs. neutral) using paired 2-sample 2-tailed t-tests.

Results

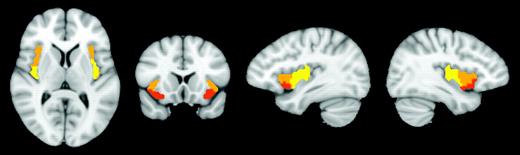

Cluster analysis revealed 3 subregions of the insula, for both left and right ROIs (Fig. 1): ventral anterior insula (vAI), dorsal anterior insula (dAI), and posterior insula (PI). Mean coordinates for each cluster are provided in Table 1. The clusterings for left and right insula ROIs were similar overall. One noteworthy difference was that the PI cluster extended further anteriorly on the left than on the right; this difference was robust to multiple iterations of the k-means algorithm.

Mean coordinates of insular subregions, in MNI152 space

| Regions | Mean coordinates (mm) | ||

| x | y | z | |

| Left ventral anterior insula | −33 | 13 | −7 |

| Right ventral anterior insula | 32 | 10 | −6 |

| Left dorsal anterior insula | −38 | 6 | 2 |

| Right dorsal anterior insula | 35 | 7 | 3 |

| Left posterior insula | −38 | −6 | 5 |

| Right posterior insula | 35 | −11 | 6 |

| Regions | Mean coordinates (mm) | ||

| x | y | z | |

| Left ventral anterior insula | −33 | 13 | −7 |

| Right ventral anterior insula | 32 | 10 | −6 |

| Left dorsal anterior insula | −38 | 6 | 2 |

| Right dorsal anterior insula | 35 | 7 | 3 |

| Left posterior insula | −38 | −6 | 5 |

| Right posterior insula | 35 | −11 | 6 |

Mean coordinates of insular subregions, in MNI152 space

| Regions | Mean coordinates (mm) | ||

| x | y | z | |

| Left ventral anterior insula | −33 | 13 | −7 |

| Right ventral anterior insula | 32 | 10 | −6 |

| Left dorsal anterior insula | −38 | 6 | 2 |

| Right dorsal anterior insula | 35 | 7 | 3 |

| Left posterior insula | −38 | −6 | 5 |

| Right posterior insula | 35 | −11 | 6 |

| Regions | Mean coordinates (mm) | ||

| x | y | z | |

| Left ventral anterior insula | −33 | 13 | −7 |

| Right ventral anterior insula | 32 | 10 | −6 |

| Left dorsal anterior insula | −38 | 6 | 2 |

| Right dorsal anterior insula | 35 | 7 | 3 |

| Left posterior insula | −38 | −6 | 5 |

| Right posterior insula | 35 | −11 | 6 |

Three subregions of the right insula identified with cluster analysis. Ventral anterior insula (red), dorsal anterior to middle insula (orange), and posterior insula (yellow). Showing slices x = 36, x = −36, y = 14, z = 9. Images are in radiological convention.

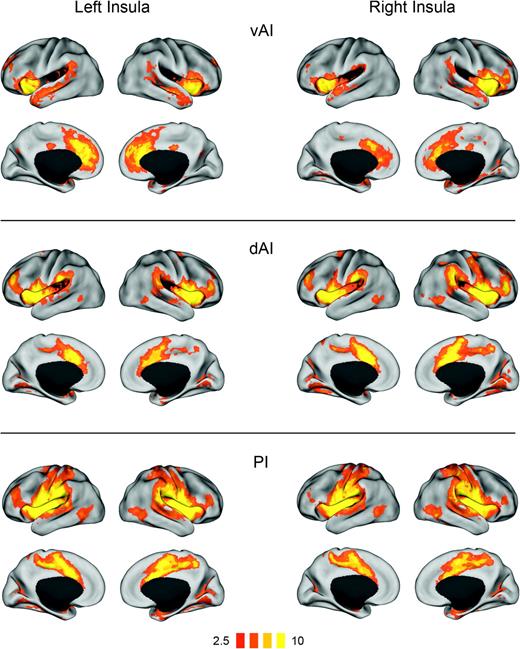

Results from whole-brain connectivity analyses using the insular clusters as seed regions are shown in Figure 2. Connectivity maps were largely similar for seed regions in the left and right hemispheres. Active regions in all 3 connectivity analyses constituted one or several large continguous clusters even at high thresholds (q < 0.001), making it difficult to report active regions in tabular form.

Functional connectivity (t-maps) of insular subregions: ventral anterior insula (vAI), dorsal anterior insula (dAI), and posterior insula (PI). Connectivity maps for left hemisphere seeds are shown on the left; maps for right hemisphere seeds are on the right.

The vAI connectivity analysis revealed correlations with much of the insula and adjacent frontal and temporal opercula, as well as nearby inferior frontal gyrus (IFG). vAI was also functionally connected with pACC and adjacent dorsal ACC, as well as anterior and posterior sections of the superior temporal sulcus.

The dAI cluster was functionally connected with the entire insula and adjacent regions (frontal, temporal, and parietal opercula, and posterior orbitofrontal cortex), as well as regions of a previously described control network (Dosenbach et al. 2007), including the dACC and adjacent pre-supplementary motor area (pre-SMA), supramarginal gyrus, ventral precentral sulcus, and anterior IFG. Weaker but significant connectivity was found with regions implicated in the control of attention, including dorsal precentral sulcus (around the frontal eye fields), intraparietal sulcus, and posterior lateral temporal cortex (around area MT). dAI also correlated with areas in the calcarine sulcus, lingual gyrus, and medial thalamus.

The PI-seeded connectivity analysis showed correlations with the entire insula and adjacent frontal, temporal, and parietal opercula, as well as the SMA and pre-SMA, much of precentral and postcentral gyri and the central sulcus, lateral temporal cortex (around MT), and a medial thalamic region, as shown in Figure 4. PI was also functionally connected with dACC and anterior IFG, as were all the insula subregions.

Two- and 4-cluster solutions, and associated connectivity maps, are given in Supplementary Figures 1 and Supplementary Data, respectively. The k = 2 solution segregated the insula into anterior and posterior divisions, without any separation of dorsal and ventral anterior insula. In the k = 4 solution, the dorsal anterior insula region was further subdivided into rostral and caudal sections (r-dAI and c-dAI). The connectivity profiles of rostral and caudal dAI were very similar; the primary difference was in the magnitude of correlation strengths, which were generally stronger for the c-dAI seed. The correlation between functional connectivity patterns (t-maps) for r-dAI and c-dAI seeds was 0.89 for the left hemisphere seeds and 0.84 for the right.

Results from the ROI-based connectivity analyses are shown in Figure 3. Fifteen of the 18 connections considered had beta values significantly greater than zero (P < 0.05, 2-tailed); no significant connection was found between pACC and right dAI, left PI, or right PI. For the pACC, we found significantly greater functional connectivity with vAI than dAI bilaterally (left insula, t29 = 4.59, P < 10−4; right insula, t = 4.53, P < 10−4), greater connectivity with vAI than PI bilaterally (left, t = 6.97, P < 5 × 10−7; right, t = 4.66, P < 10−4), and greater connectivity with dAI than PI for the left but not right insula (t = 5.16, P < 5 × 10−5). For the dorsal ACC, significantly greater connectivity was found with dAI versus vAI (left, t = 3.18, P < 0.005; right, t = 2.41, P < 0.05) and with dAI versus PI (left, t = 4.29, P < 5 × 10−4; insula, t = 2.21, P < 0.05). Lastly, for the MCC, we found stronger connectivity with PI versus dAI (left, t = 5.16, P < 0.005; right, t = 2.15, P < 0.05), with PI versus vAI (left, t = 6.90, P < 5 × 10−7; right, t = 5.06, P < 5 × 10−5), and with dAI versus vAI (left, t = 5.16, P < 5 × 10−5; right, t = 2.22, P < 0.05). These results demonstrate statistically that the pACC is most strongly functionally connected to ventral anterior insula, dorsal ACC is most strongly connected to dorsal anterior insula, and MCC is most strongly connected to the posterior insula, consistent with the whole-brain connectivity results.

ROI analysis results. Connectivity strength (beta) between 3 insula subregions from cluster analysis (ventral anterior, vAI; dorsal anterior, dAI; and posterior, PI) and 3 spherical ROIs along middle to ACC (pregenual anterior, pACC; dorsal anterior, dACC; and middle, MCC). Error bars give standard error.

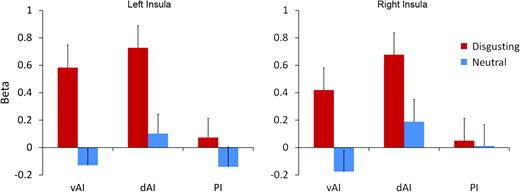

Evoked BOLD response of insula subregions vAI, dAI, and PI to disgusting and neutral images.

Task-evoked responses of insula clusters to disgusting and neutral images are given in Figure 4. Significant evoked responses to disgusting images were found in bilateral dorsal AI (left, t19 = 4.54, P < 5 × 10−4; right, t = 4.20, P < 5 × 10−4) and ventral AI (left, t = 4.15, P < 0.001; right, t = 2.59, P < 0.05); no significant responses to neutral images were found. Significantly, greater responses to disgusting versus neutral images were also found in both dorsal AI (left, t = 4.34, P < 5 × 10−4; right, t = 3.21, P < 0.005) and ventral AI (left, t = 4.94, P < 10−4; right, t = 3.87, P < 0.005). Activity in the posterior insula was not significantly modulated by the presence of images nor by image valence.

Furthermore, we performed post hoc tests comparing response magnitudes in vAI and dAI to investigate a possible functional dissociation between these regions. We found a stronger response to neutral images in dAI versus vAI bilaterally (left, t = 2.36, P < 0.05; right, t = 4.46, P < 5 × 10−4) and a stronger response to disgusting images in dAI versus vAI for the right insula only (t = 2.88, P < 0.01), consistent with the claim that dAI is more generally responsive to images than vAI.

Discussion

The present study demonstrates that the human insula comprises at least 3 subsystems with distinct patterns of large-scale functional connectivity. The spatial arrangement of these regions, falling along trajectory from ventral anterior to dorsal posterior insula, corresponds roughly to known cytoarchitectonic patterns in the insula (Mesulam and Mufson 1982a; Augustine 1996). The results demonstrate a dissociation in the connectivity profiles of dorsal and ventral aspects of the anterior insula, which has not been emphasized in the prior literature. More generally, we show that data-driven clustering methods applied to resting-state functional connectivity data can yield useful and functionally meaningful subdivisions of cerebral cortex.

The posterior insula was found to be functionally connected to primary and secondary motor and somatosensory cortices, having greatest connectivity with secondary and adjacent primary somatosensory cortex. These regions closely resemble the bilateral somatomotor network that has been found using seeds in precentral/postcentral gyrus or SMA or using data-driven methods such as independent component analysis (Biswal et al. 1995; Lowe et al. 1998; Beckmann et al. 2005). This pattern of functional connectivity with PI is consistent with studies of anatomical connectivity in the macaque, which show that PI has reciprocal connections with SMA and secondary somatosensory cortex (Mesulam and Mufson 1982b; Mufson and Mesulam 1982; Friedman et al. 1986). However, the insula is not extensively connected to primary motor or somatosensory cortex in the macaque. Functional correlations between insula and primary motor/somatosensory cortices observed in the present study may result from indirect connections between these regions (perhaps through secondary motor/somatosensory cortex) or may reflect the influence of a third region driving both areas.

The observed pattern of PI functional connectivity is also consistent with the somatosensory/interoceptive role of PI (Schneider et al. 1993; Augustine 1996; Craig 2002; McGlone et al. 2002; Olausson et al. 2002). The posterior insula receives afferent projections from the lamina I spinothalamocortical pathway carrying nociceptive, thermal, and other interoceptive information (Craig 2002). PI also receives signals from unmyelinated (C) tactile afferents, responding specifically to slow stroking tactile stimulation, characteristic of human contact (Olausson et al. 2002). Thus, the posterior insula may be generally involved in processing somatosensory stimuli with affective or motivational significance (Augustine 1996; Craig 2002, 2009).

The ventral anterior insula was most strongly correlated with pACC. This is roughly consistent with anatomical connections in the macaque, in which pregenual cingulate cortex receives projections from ventral anterior insula (Vogt and Pandya 1987). A correlation between vAI and pACC was also found by Margulies et al. (2007), in a cingulate-seeded connectivity analysis; vAI and pACC were also included in the salience network described by Seeley et al. (2007). Using our pACC ROI as a seed in a whole-brain connectivity analysis with the same set of 30 subjects, we found correlations with regions of the default mode network (DMN), including medial prefrontal cortex, posterior cingulate cortex, and bilateral angular gyrus; interestingly, core DMN regions are in turn anticorrelated with dACC and dAI (Fox et al. 2005; Chang and Glover 2009).

Several prior findings indicate a role for ventral AI in the processing of emotion. Among insular subregions, ventral anterior insula is cytoarchitectonically closest to limbic cortex and has the most extensive connections with other allocortical regions (Mesulam and Mufson 1982a, 1982b; see also Dupont et al. 2003). A recent activation likelihood estimation–based meta-analysis found that peak coordinates from studies relating brain activity to peripheral physiological responses resulting from emotional experiences, such as heart rate or galvanic skin response, tended to lie in vAI (Mutschler et al. 2009). These authors also found that vAI was the most likely site of insular coactivation with the amygdala. A number of studies have found activation in the anterior insula, both dorsal and ventral, during the experience of pain (Coghill et al. 1994; Casey et al. 1996; Svensson et al. 1997; Derbyshire et al. 1997; Peyron et al. 2000; Kong et al. 2006); however, such responses could relate either to the subjective, emotional dimension of pain, or to the engagement of more general attentional or cognitive response. Baliki et al. (2009) found that while the estimation of pain magnitude and visual length similarly engaged the dorsal AI, ventral AI was more strongly activated by the experience of pain, pointing to a specific role of vAI in processing pain.

The dorsal anterior insula was found to be functionally connected to a set of regions previously described as a cognitive control network (Dosenbach et al. 2007). Prior research has indicated a broad role of these regions, and particularly the anterior insula and anterior cingulate, in the implementation of goal-directed tasks: using 10 different cognitive tasks, Dosenbach et al. (2007) showed that dAI and dACC consistently showed sustained activity throughout task performance, as well as a brief spike of activation at the onset of each task. Other studies have pointed to a role of the dAI/dACC network in decision making: Activity in these regions has been shown to increase with the degree of difficulty or uncertainty in a decision (Critchley et al. 2001; Grinband et al. 2006; Thielscher and Pessoa 2007), and Ploran et al. (2007) found a spike of activity in this network time-locked to the “moment of recognition” in a perceptual discrimination task. These observations may all relate to a general role of dAI/dACC in cognitive control. Given this evidence, this network might form a pathway by which information in the insula, such as somatosensory/interoceptive information from PI or affective information from vAI, can influence decision making and behavior.

Results from the ROI analysis demonstrate a gradient in which anterior regions of cingulate cortex are most correlated with ventral anterior parts of the insula, while more posterior regions of cingulate cortex correlate with more dorsal and posterior insula. This replicates and extends the finding of 2 systems of cingulo-insular connectivity by Taylor et al. (2009), and generally agrees with patterns of anatomical connectivity in the macaque (Mesulam and Mufson 1982b; Mufson and Mesulam 1982; Vogt and Pandya 1987). Differences in connectivity of dorsal and ventral AI may relate to the aforementioned emotional/cognitive roles of these 2 regions: evidence from cytoarchitectonics and connectivity in the macaque and neuroimaging in humans points to a functional dissociation in which pregenual and subgenual ACC are primarily involved in emotional function, while dorsal parts of ACC are more involved in cognitive function (Devinsky et al. 1995; Bush et al. 2000; Steele and Lawrie 2004). Thus, our results indicate the presence of 2 closely linked but dissociable networks of anterior insular and cingulate regions: a dorsal network primarily involved in cognitive control and a ventral network more involved in emotional experience. Evidence for a close relation between these networks comes from the finding that dorsal and ventral anterior insula were combined in our 2-cluster solution (Supplementary Figure 1); similarly, these networks appear to combine to form the salience network identified by Seeley et al. (2007).

The results presented here provide convergent evidence with a prior study that used clustering of DTI-based connectivity patterns to separate the left insula into 2 subregions, anterior and posterior (Nanetti et al. 2009). Our 2-cluster solution for the left insula (Supplementary Figure 2) closely resembles their result, indicating that cortical parcellation based on DTI and resting-state functional connectivity may yield similar results; this is broadly consistent with the claim that resting-state correlations reflect structural connections between regions. Nanetti et al. (2009) note that multiple iterations of the k-means algorithm, with different initial clusterings, can lead to divergent anatomical parcellations. The present analyses show that using the solution that minimizes within-cluster variance can lead to anatomically meaningful solutions, at least for the insula.

Results from the task analysis demonstrate that insular subregions defined using clustering of connectivity patterns are functionally meaningful regions, with distinct response profiles to disgusting and neutral images. As expected from prior research, anterior regions of the insula responded selectively to disgusting images, while posterior insula did not. The anterior insula is continuous with primary gustatory cortex in dorsal AI/frontal operculum and adjacent ventrally to primary olfactory cortex (Ogawa 1994; Small et al. 1999; Zald and Pardo 2000). The anterior insula has been associated with disgust processing, primarily from neuropsychological studies showing a deficit in the experience and recognition of disgust in anterior insular lesion patients (Calder et al. 2000; Adolphs et al. 2003; see also Kipps et al. 2007).

Functional imaging studies also show anterior insula activation in response to unpleasant or disgusting odorants and aversive tastes (Zald et al. 1998; Heining et al. 2003; Royet et al. 2003; Small et al. 2003; Wicker et al. 2003), disgusting images (Schienle et al. 2002; Calder et al. 2007), and images or film clips of facial expressions of disgust (Phillips et al. 1997, 1998; Wicker et al. 2003; Jabbi et al. 2007; see also Krolak-Salmon et al. 2003). These studies have found activations in one or both of dorsal and ventral anterior insular cortex, but prior research has not attempted to dissociate the function of these activations. The ventral AI, in particular, has been consistently found to be modulated by the hedonic valence of olfactory and gustatory stimuli (Heining et al. 2003; Royet et al. 2003; Small et al. 2003) and may be a site for olfactory–gustatory convergence and taste perception (de Araujo et al. 2003). Based on the above arguments on the relative roles of dAI and vAI, we speculate that ventral anterior activations to disgusting stimuli may reflect an earlier sensory and affective response to disgusting stimuli, while the dAI is involved in linking this affective response to attentional or executive mechanisms in order to respond to this aversive event. We also show that dAI is generally more responsive to images than vAI, consistent with a broad attentional or cognitive role of the dorsal AI.

The present study implemented a novel approach to identify patterns of functional connectivity of insular subregions in a data-driven manner. This provides a method for functional parcellation of cerebral cortical regions based on a single brief, task-free resting-state scan, and has the potential to yield novel insights into functional connectivity in the human brain, such as the dissociation between connectivity profiles of dorsal and ventral anterior insula presented here. ROI-based assessment of regional connectivity and evoked responses to neutral and disgusting images demonstrates that our method yields functionally meaningful subregions, with distinct connectivity and task-related activation. Our task results also suggest that cortical regions defined using functional connectivity may be useful as ROIs in functional imaging studies, defined independently from task-evoked responses (cf. Vul et al. 2009). Future research should more closely investigate the relationship between insular subregions defined by functional connectivity and by other properties, such as cytoarchitectonic divisions or DTI-based tractography (cf. Anwander et al. 2007; Beckmann et al. 2009; Nanetti et al. 2009). Subsequent research should also further probe the response properties of the 3 regions identified here to determine the full functional roles of insular subregions.

Funding

Simons Foundation; John Merck Scholars Fund; Autism Speaks grants to K.P.; National Institute of Mental Health Career Development Award (K01 MH071284 to K.P.); Doris Duke Charitable Foundation fellowship to N.B.P.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.