Abstract

Social assistance benefit schemes are a peculiar type of welfare state program. As the electoral costs are relatively low, this program forms an obvious target for cost reduction in times of austerity. The aim of this study is to examine the determinants of the developments in social assistance benefits. We seek to make two contributions. First, this paper provides insight into the role of economic, political, and institutional determinants of the variation in social assistance benefits. Second, cross-national data on social expenditures and income replacement rates are available for several welfare state programs, but not for social assistance benefits. Presenting minimum income benefit replacement rates, this study analyzes the developments of social assistance benefits across 26 OECD countries over the past two decades. The analysis leads to the conclusion that budgetary pressure stemming from increased exposure to international trade and soaring levels of unemployment is associated with benefit cuts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

For a detailed analysis of micro-level mechanisms, see Rehm (2016).

One-time social assistance allowances to cover unexpected and urgent needs or regular benefits to cover exceptional needs are not included in this benefit package. Furthermore, housing supplements are not included. The inclusion of housing supplements requires a number of demanding assumptions. Van Mechelen et al. (2011) have shown that the assumptions regarding the actual housing costs strongly determine the resulting benefit indicators. Therefore, we follow Scruggs’ (2005) approach and exclude the housing supplements from our minimum income benefit package.

An important aspect of social assistance benefit programs is the coverage rate or take-up rate, which measures the extent to which individuals are entitled to the benefits. Recently, the OECD has published the Social Benefit Recipients Database but the data for social assistance benefit recipients are only available for the period 2007–2012 for lone parents (OECD 2016). These data show that between 2008 and 2012, long-term unemployment has surged and the number of recipients of social assistance increased. Longitudinal internationally comparable information on coverage rates of social assistance benefit recipients is scarce. Therefore, we do not include the coverage rate in our analysis.

A sensitivity analysis reported below indicates that the regression results are not contingent on these large changes in the Central and Eastern European countries.

We have also examined indirect effects of the domestic institutions by including interaction variables between globalization and unemployment rates and institutional variables. We did not find robust results for such indirect effects.

The difference in developments between trade and capital openness is even larger for the years 1990 and 2009 (instead of 2008), as FDI decreased substantially as a result of the financial crisis in 2009.

References

Adema, W. 2006. Social assistance policy development and the provision of a decent level of income in selected OECD countries. OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers no. 38. Paris: OECD.

Allan, J.P., and L. Scruggs. 2004. Political partisanship and welfare state reform in advanced industrial societies. American Journal of Political Science 48(3): 496–512.

Ansell, B., and J. Gingrich. 2013. A tale of two trilemmas: Varieties of higher education and the service economy. In The Political Economy of the Service Transition, ed. A. Wren, 195–224. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Armingeon, K., D. Weisstanner, S. Engler, P. Potplidis, and M. Gerber. 2012. Comparative Political Data Set III. Berne: University of Berne.

Beck, N., and J.N. Katz. 2011. Modeling dynamics in time-series-cross-section political economy data. Annual Review of Political Science 14: 331–352.

Beck, T., G. Clarke, A. Groff, P. Keefer, and P. Walsh. 2001. New tools in comparative political economy: The Database of Political Institutions. The World Bank Economic Review 15(1): 165–176.

Bonoli, G. 2001. Political institutions, veto points, and the process of welfare adaptation. In The New Politics of the Welfare State, ed. P. Pierson, 238–264. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Brady, D., J. Beckfield, and M. Seeleib-Kaiser. 2005. Economic globalization and the welfare state in affluent democracies, 1975–2001. American Sociological Review 70(6): 921–948.

Burgoon, B. 2001. Globalization and welfare compensation: Disentangling the ties that bind. International Organization 55(03): 509–551.

Busemeyer, M.R. 2009. From myth to reality: Globalisation and public spending in OECD countries revisited. European Journal of Political Research 48(4): 455–482.

Cantillon, B., and K. Van den Bosch. 2002. Back to basics: The case for an adequate minimum guaranteed income in the active welfare states. In Trade, Competitiveness and Social Protection, ed. J. Pacolet, and E. Claessens, 73–94. Canada: APF Press.

Clegg, D. 2014. Convergence from below? The reform of minimum income protection in France and the UK. Journal of International and Comparative Social Policy 30(2): 147–164.

Danforth, B., and J.D. Stephens. 2013. Measuring social citizenship: Achievements and future challenges. Journal of European Public Policy 20(9): 1285–1298.

De Boef, S., and L. Keele. 2008. Taking time seriously. American Journal of Political Science 52(1): 184–200.

Dreher, A. 2006. The influence of globalization on taxes and social policy: An empirical analysis for OECD countries. European Journal of Political Economy 22(1): 179–201.

Ebbinghaus, B., and A. Hassel. 2000. Striking deals: Concertation in the reform of continental European welfare states. Journal of European Public Policy 7(1): 44–62.

Figari, F., M. Matsaganis, and H. Sutherland. 2013. Are European social safety nets tight enough? Coverage and adequacy of minimum income schemes in 14 EU countries. International Journal of Social Welfare 22(1): 3–14.

Garrett, G., and D. Mitchell. 2001. Globalization, government spending and taxation in the OECD. European Journal of Political Research 39(2): 145–177.

Gaston, N., and G. Rajaguru. 2008. The rise (and fall) of labour market programmes: Domestic vs. global factors. Oxford Economic Papers 60: 619–648.

Häusermann, S., G. Picot, and D. Geering. 2013. Review article: Rethinking party politics and the welfare state—Recent advances in the literature. British Journal of Political Science 43(1): 221–240.

Hays, J.C. 2009. Globalization and the New Politics of Embedded Liberalism. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Henisz, W.J. 2002. The institutional environment for infrastructure investment. Industrial and Corporate Change 11(2): 355–389.

Heston, A., R. Summers, and A. Bettina. 2012. Penn World Table Version 7.1. Pennsylvania: University of Pennsylvania.

Hicks, A., and K. Freeman. 2009. Pension income replacement: Permanent and transitory determinants. Journal of European Public Policy 16(1): 127–143.

Hicks, A., and C. Zorn. 2005. Economic globalization, the macro economy, and reversals of welfare: Expansion in affluent democracies, 1978–94. International Organization 59(03): 631–662.

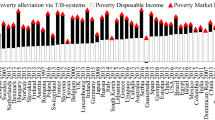

Hölsch, K., and M. Kraus. 2004. Poverty alleviation and the degree of centralization in European schemes of social assistance. Journal of European Social Policy 14(2): 143–164.

Huber, E., and J.D. Stephens. 1998. Internationalization and the social democratic model: Crisis and future prospects. Comparative Political Studies 31(3): 353–397.

Huber, E., and J.D. Stephens. 2001. Partisan Choice in Global Markets: Developments and Crisis of Advanced Welfare States. Chicago: University Press of Chicago.

Immervoll, H., S. P. Jenkins, and S. Königs. 2015. Are recipients of social assistance ‘benefit dependent’? Concepts, measurement and results for selected countries. OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers no. 162. Paris: OECD.

Iversen, T., and T.R. Cusack. 2000. The causes of welfare state expansion: Deindustrialization or globalization? World Politics 52(03): 313–349.

Iversen, T., and D. Soskice. 2006. Electoral institutions and the politics of coalitions: Why some democracies redistribute more than others. American Political Science Review 100(2): 165–181.

Jensen, C. 2012. Labour market- versus life course-related social policies: Understanding cross-programme differences. Journal of European Public Policy 19(2): 275–291.

Jensen, C., and P.B. Mortensen. 2014. Government responses to fiscal austerity: The effect of institutional fragmentation and partisanship. Comparative Political Studies 47(2): 143–170.

Korpi, W., and J. Palme. 2003. New politics and class politics in the context of austerity and globalization: Welfare state regress in 18 countries, 1975–95. American Political Science Review 97(03): 425–446.

Leibrecht, M., M. Klien, and Ö. Onaran. 2011. Globalization, welfare regimes and social protection expenditures in Western and Eastern European countries. Public Choice 148(3–4): 569–594.

Lødemel, I., and A. Moreira. 2014. Activation or Workfare? Governance and the Neo-liberal Convergence. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Marchal, S., I. Marx, and N. Van Mechelen. 2014. The Great Wake-Up Call? Social citizenship and minimum income provisions in Europe in times of crisis. Journal of social policy 43(02): 247–267.

Martin, C.J., and D. Swank. 2004. Does the organization of capital matter? Employers and active labor market policy at the national and firm levels. American Political Science Review 98(04): 593–611.

Nelson, K. 2008. Minimum income protection and European Integration: Trends and levels of minimum benefits in comparative perspective, 1990–2005. International Journal of Health Services 38(1): 103–124.

Nelson, K. 2012. Counteracting material deprivation: The role of social assistance in Europe. Journal of European Social Policy 22(2): 148–163.

Nelson, K. 2013. Social assistance and EU poverty thresholds 1990–2008. Are European welfare systems providing just and fair protection against low income? European Sociological Review 29(2): 386–401.

Nickell, S. 1981. Biases in dynamic models with fixed effects. Econometrica 49(6): 1417–1426.

OECD. 2014. Labor Force Statistics. Paris: OECD.

OECD. 2015. In It Together: Why Less Inequality Benefits All. Paris: OECD.

OECD. 2016. Social Benefit Recipients Database. Paris: OECD.

Offe, C. 1991. Smooth consolidation in the West German welfare states. In Labour Parties in Postindustrial Societies, ed. F. Fox Piven, 124–146. New York: Policy Press.

Olson, M. 1965. The Logic of Collective Action: Public Goods and the Theory of Groups. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Pierson, P. 2001. Coping with permanent austerity: Welfare state restructuring in affluent democracies. In The New Politics of the Welfare State, ed. P. Pierson, 410–456. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Potrafke, N. 2016. Partisan Politics: The Empirical Evidence from OECD Panel Studies. CESifo Working Paper no. 6024.

Rehm, P. 2016. Risk Inequality and Welfare States: Social Policy Preferences, Development and Dynamics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Rodrik, D. 1998. Why do more open economies have bigger governments. Journal of Political Economy 106(5): 997–1002.

Ross, F. 2000. ‘Beyond left and right’: The new partisan politics of welfare. Governance 13: 155–183.

Rothstein, B. 1992. Labor-market institutions and working-class strength. In Structuring Politics: Historical Institutionalism in Comparative Analysis, ed. S. Steinmo, K. Thelen, and F. Longstreth, 33–56. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Rueda, D. 2007. Social Democracy Inside Out: Partisanship and Labor Market Policy in Industrialized Democracies. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Saint-Paul, G. 1996. Exploring the political economy of labour market institutions. Economic Policy 23: 263–315.

Scheve, K., and M.J. Slaughter. 2004. Economic insecurity and the globalization of production. American Journal of Political Science 48(4): 662–674.

Scruggs, L. 2005. Welfare state entitlement data set: A comparative institutional analysis of eighteen welfare states. Version 1: 1.

Swank, D. 2002. Global Capital, Political Institutions, and Policy Change in Developed Welfare States. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Swank, D. 2011. Activating workers? The political economy of active social policy in postindustrial democracies. In Comparing European Workers Part B: Policies and Institutions, ed. D. Brady, 9–51. Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

Swank, D. 2013. Party government, institutions, and social protection in the age of austerity. In Staatstätigkeiten, Parteien und Demokratie, ed. K. Armingeon, 307–330. Wiesbaden: Springer.

Van Kersbergen, K., B. Vis, and A. Hemerijck. 2014. The great recession and welfare state reform: Is retrenchments really the only game left in town? Social Policy & Administration 48(7): 883–904.

Van Mechelen, N., and S. Marchal. 2013. Struggle for life: Social assistance benefits, 1992–2009. In Minimum Income Protection in Flux, ed. I. Marx, and K. Nelson, 28–53. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Van Mechelen, N., S. Marchal, T. Goedeme, I. Marx, and B. Cantillon 2011. The CSB-Minimum Income Protection Indicators Dataset (CSB-MIPI). CSB Working Paper no. 05/2011.

Van Oorschot, W. 2006. Making the difference in social Europe: Deservingness perceptions among citizens of European welfare states. Journal of European Social Policy 16(1): 23–42.

Van Vliet O., and K. Caminada. 2012. Unemployment replacement rates dataset among 34 welfare states 1971–2009: An update, extension and modification of Scruggs’ Welfare State Entitlements Data Set NEUJOBS Special Report nr. 2. Leiden University.

Visser, J. 2013. Database on Institutional Characteristics of Trade Unions, Wage Setting, State Intervention and Social Pacts in 34 Countries between 1960 and 2012 (ICTWSS). Version 4, April 2013. Amsterdam: University of Amsterdam.

Wallerstein, M. 1989. Union growth in advanced industrial democracies. American Political Science Review 83: 481–501.

Walter, S. 2017. Globalization and the demand-side of politics: How globalization shapes labor market risk perceptions and policy preferences. Political Science Research Methods 5(1): 55–80.

Wang, J., and O. Van Vliet. 2016a. Social assistance and minimum income benefits: Benefit levels, replacement rates and policies across 26 OECD countries, 1990–2009. European Journal of Social Security 18(4): 333–355.

Wang, J., and O. Van Vliet. 2016b. Social Assistance and Minimum Income Levels and Replacement Rates Dataset. Leiden University. http://www.universiteitleiden.nl/en/law/institute-for-tax-law-and-economics/economics/data-sets/the-social-assistance-and-minimum-income-levels-and-replacement-rates-dataset.

Whiteford, P. 1995. The use of replacement rates in international comparisons of benefit systems. International Social Security Review 48(2): 3–30.

World Bank. 2012. World Development Indicators. Washington: World Bank.

Acknowledgements

An earlier version of this paper was presented at the 23rd International Conference of Europeanists (CES, 2016). We thank all participants and Koen Caminada, Kees Goudswaard, Carlo Knotz, Michal Polakowski, David Rueda, Duane Swank, Dorota Szelewa, Stefan Thewissen, Tim Vlandas and Chen Wang for useful comments and suggestions. The study has received support from the European Commission’s 7th Framework Program under Grant Agreement no. 312691, InGRID—Inclusive Growth Research Infrastructure Diffusion.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

van Vliet, O., Wang, J. The political economy of social assistance and minimum income benefits: a comparative analysis across 26 OECD countries. Comp Eur Polit 17, 49–71 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41295-017-0109-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41295-017-0109-7