Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This review synthesizes available evidence for managing clinically significant dysphoric symptoms encountered in primary care, when formal criteria for major depression or dysthymia are not met. Discussion is focused on premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD) and minor depression because of their significant prevalence in the primary care setting and the lack of clear practice guidelines for addressing each illness.

DESIGN: English language literature from prior systematic reviews was supplemented by searching medline, embase, the Cochrane Controlled Trials Registry, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality National Guideline Clearinghouse, and bibliographies of selected papers. Studies addressing the natural history or treatment of minor depression or PMDD were selected for review. Data were abstracted by 1 of 2 independent reviewers and studies were synthesized qualitatively.

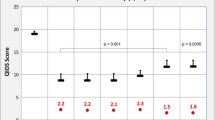

RESULTS: Five individual studies that compared anti-depressant or psychological treatments to placebo in patients with minor depression suggest short-term improvements in depressive symptoms with paroxetine, problem-solving therapy, and cognitive behavioral therapy, but not with amitryptiline. Modest benefits on mental health function were reported with paroxetine and with problem-solving therapy, but only in patients with severe functional impairment at baseline. Twenty-four controlled trials were identified that compared antidepressant or psychological treatments to placebo in patients with premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Pooled results from a recent systematic review of 15 randomized controlled trials and one additional trial abstract provide strong evidence for a significantly greater improvement in physical and psychological symptoms with serotonin-selective reuptake inhibitor medications when compared with placebo. Individual trials also suggest significantly greater improvements in symptom scores with venlafaxine, but not with tricyclic antidepressants.

CONCLUSIONS: The limited evidence base for minor depression provides only mixed support for a small to moderate benefit for few antidepressant medications and psychological treatments tested. For the treatment of severe psychological or physical symptoms causing functional impairment in patients with PMDD, sertraline and fluoxetine are clearly beneficial in carefully selected patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Williams JW Jr., Mulrow CD, Chiquette E, Noel PH, Aguilar C, Cornell J. A systematic review of newer pharmacotherapies for depression in adults: evidence report summary. Ann Intern Med. 2000;132:743–56.

Mulrow CD, Williams JW Jr., Trivedi M, et al. Treatment of depression: new pharmacotherapies. AHCPR Publication No. 99-E014. Rockville, Md: Agency for Health care Policy and Research; 1999.

Depression Guideline Panel. Depression in primary care. Vol 2: Treatment of Major Depression. Clinical Practice Guideline, no. 5. Rockland, Md: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Agency for Health Care Policy and Research; 1993.

Beck DA, Koenig HG. Minor depression: a review of the literature. Int J Psychiatry Med. 1996;26:177–209.

Crum RM, Cooper-Patrick L, Ford DE. Depressive symptoms among general medical patients: prevalence and one-year outcome. Psychosom Med. 1994;56:109–17.

Depression Guideline Panel. Depression in primary care. Vol 1: Detection and Diagnosis. Clinical Practice Guideline, no. 5. Rockville, Md: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Agency for Health Care Policy and Research; 1993.

Pincus HA, Davis WW, McQueen LE. ‘Subthreshold’ mental disorders. A review and synthesis of studies on minor depression and other ‘brand names’. Br J Psychiatry. 1999;174:288–96.

Maier W, Gansicke M, Weiffenbach O. The relationship between major and subthreshold variants of unipolar depression. J Affect Disord. 1997;45:41–51.

Wells KB, Stewart A, Hays RD, et al. The functioning and well-being of depressed patients. Results from the Medical Outcomes Study. JAMA. 1989;262:914–9.

Johnson J, Weissman MM, Klerman GL. Service utilization and social morbidity associated with depressive symptoms in the community. JAMA. 1992;267:1478–83.

Williams JW Jr., Rost K, Dietrich AJ, Ciotti MC, Zyzanski SJ, Cornell J. Primary care physicians’ approach to depressive disorders. Effects of physician specialty and practice structure. Arch Fam Med. 1999;8:58–67.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-IV. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1994.

Jarrett RB. Psychosocial aspects of depression and the role of psychotherapy. J Clin Psychiatry. 1990;51:26S-35S.

Mynors-Wallis LM, Gath DH, Lloyd-Thomas AR, Tomlinson D. Randomised controlled trial comparing problem solving treatment with amitriptyline and placebo for major depression in primary care. BMJ. 1995;310:441–5.

Broadhead WE, Blazer DG, George LK, Tse CK. Depression, disability days, and days lost from work in a prospective epidemiologic survey. JAMA. 1990;264:2524–8.

Association of Professors of Gynecology and Obstetrics. Depressive disorders in women: diagnosis, treatment, and monitoring. Washington, DC: Association of Professors of Gynecology and Obstetrics; 1997.

Dimmock PW, Wyatt KM, Jones PW, O’Brien PM. Efficacy of selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors in premenstrual syndrome: a systematic review. Lancet. 2000;356:1131–6.

Steiner M, Streiner DL, Steinberg S, et al. The measurement of premenstrual mood symptoms. J Affect Disord. 1999;53:269–73.

Pearlstein TB, Frank E, Rivera-Tovar A, Thoft JS, Jacobs E, Mieczkowski TA. Prevalence of axis I and axis II disorders in women with late luteal phase dysphoric disorder. J Affect Disord. 1990;20:129–34.

Paykel ES, Hollyman JA, Freeling P, Sedgwick P. Predictors of therapeutic benefit from amitriptyline in mild depression: a general practice placebo-controlled trial. J Affect Disord. 1988;14:83–95.

Parnetti L, Sommacal S, Morselli Labate AM, Senin U. Multicentre controlled randomised double-blind pracebo study of minaprine in elderly patients suffering from prolonged depressive reaction. Drug Invest. 1993;6:181–8.

Williams JW Jr., Barrett J, Oxman T, et al. Treatment of dysthymia and minor depression in primary care: a randomized controlled trial in older adults. JAMA. 2000;284:1519–26.

Miranda J, Munoz R. Intervention for minor depression in primary care patients. Psychosom Med. 1994;56:136–41.

Lynch DJ, Tamburrino MB, Nagel R. Telephone counseling for patients with minor depression: preliminary findings in a family practice setting. J Fam Pract. 1997;44:293–8.

Katon W, Von Korff M, Lin E, et al. Collaborative management to achieve treatment guidelines. Impact on depression in primary care. JAMA. 1995;273:1026–31.

Katon W, Robinson P, Von Korff M, et al. A multifaceted intervention to improve treatment of depression in primary care. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1996;53:924–32.

Halbreich U, Bergeron R. Intermittent (luteal phase) dosing of sertraline effective in PMDD [abstract]. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2000;3:241S-248S.

Freeman EW, Rickels K, Sondheimer SJ, Polansky M. A double-blind trial of oral progesterone, alprazolam, and placebo in treatment of severe premenstrual syndrome. JAMA. 1995;274:51–7.

Lam RW, Carter D, Misri S, Kuan AJ, Yatham LN, Zis AP. A controlled study of light therapy in women with late luteal phase dysphoric disorder. Psychiatry Res. 1999;86:185–92.

Rausch JL, Janowsky DS, Golshan S, Kuhn K, Risch SC. Atenolol treatment of late luteal phase dysphoric disorder. J Affect Disord. 1988;15:141–7.

Sundblad C, Modigh K, Andersch B, Eriksson E. Clomipramine effectively reduces premenstrual irritability and dysphoria: a placebo-controlled trial. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1992;85:39–47.

Sundblad C, Hedberg MA, Eriksson E. Clomipramine administered during the luteal phase reduces the symptoms of premenstrual syndrome: a placebo-controlled trial. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1993;9:133–45.

Harrison WM, Endicott J, Nee J. Treatment of premenstrual dysphoria with alprazolam. A controlled study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1990;47:270–5.

Berger CP, Presser B. Alprazolam in the treatment of two subsamples of patients with late luteal phase dysphoric disorder: a double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover study. Obstet Gynecol. 1994;84:379–85.

Rickels K, Freeman EW. Prior benzodiazepine exposure and benzodiazepine treatment outcome. J Clin Psychiatry. 2000;61:409–13.

Morse CA, Dennerstein L, Farrell E, Varnavides K. A comparison of hormone therapy, coping skills training, and relaxation for the relief of premenstrual syndrome. J Behav Med. 1991;14:469–89.

Kirkby RJ. Changes in premenstrual symptoms and irrational thinking following cognitive-behavioral coping skills training. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1994;62:1026–32.

Blake F, Salkovskis P, Gath D, Day A, Garrod A. Cognitive therapy for premenstrual syndrome: a controlled trial. J Psychosom Res. 1998;45:307–18.

Christensen AP, Oei TP. The efficacy of cognitive behaviour therapy in treating premenstrual dysphoric changes. J Affect Disord. 1995;33:57–63.

Corney RH, Stanton R, Newell R. Comparison of progesterone, placebo and behavioural psychotherapy in the treatment of premenstrual syndrome. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 1990;11:211–20.

Freeman EW, Rickels K, Sondheimer SJ, Polansky M. Differential response to antidepressants in women with premenstrual syndrome/premenstrual dysphoric disorder: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56:932–9.

Eriksson E, Hedberg MA, Andersch B, Sundblad C. The serotonin reuptake inhibitor paroxetin is superior to the noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor maprotiline in the treatment of premenstrual syndrome. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1995;12:167–76.

Linde K, Mulrow CD. St. John’s wort for depression [Cochrane Review]. In: The Cochrane Library. Issue 3,. Oxford: Update Software; 1999.

Shelton RC, Keller MB, Gelenberg A, et al. Effectiveness of St John’s wort in major depression: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2001;285:1978–86.

North TC, McCullagh P, Tran ZV. Effect of exercise on depression. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 1990;18:379–415.

McNeil JK, LeBlanc EM, Joyner M. The effect of exercise on depressive symptoms in the moderately depressed elderly. Psychol Aging. 1991;6:487–8.

Veale D, Le Fevre K, Pantelis C, de Souza V, Mann A, Sargeant A. Aerobic exercise in the adjunctive treatment of depression: a randomized controlled trial. J R Soc Med. 1992;85:541–4.

Blumenthal JA, Babyak MA, Moore KA, et al. Effects of exercise training on older patients with major depression. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:2349–56.

Wyatt KM, Dimmock PW, Jones PW, Shaughn O’Brien PM. Efficacy of vitamin B-6 in the treatment of premenstrual syndrome: systematic review. BMJ. 1999;318:1375–81.

Lemos D. The effects of aerobic training on women who suffer from premenstrual syndrome. Dissert Abstracts Int. 1991;52:563.

Bibi KW. The effects of aerobic training on women who suffer from premenstrual syndrome. Dissert Abstracts Int. 1995;56:6678.

Budeiri D, Li Wan Po A, Dornan JC. Is evening primrose oil of value in the treatment of premenstrual syndrome? Control Clin Trials. 1996;17:60–8.

Simon GE, Von Korff M, Heiligenstein JH, et al. Initial antidepressant choice in primary care. Effectiveness and cost of fluoxetine vs tricyclic antidepressants. JAMA. 1996;275:1897–902.

Parry GJ. Sensory neuropathy with low dose pyridoxine. Neurology. 1985;35:1466–8.

Drug interactions with St. John’s wort. Med Lett Drugs Ther. 2000;42:56.

Wolfe RM. Antidepressant withdrawal reactions. Am Fam Physician. 1997;56:455–62.

American Psychiatric Association Practice Guidelines. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with major depressive disorder (revision). Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(Suppl 4):1S-45S.

Snow V, Lascher S, Mottur-Pilson C. Pharmacologic treatment of acute major depression and dysthymia. American College of Physicians-American Society of Internal Medicine. Ann Intern Med. 2000;132:738–42.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This research was supported by the Office of Research and Development, Health Services R&D Service, Department of Veterans Affairs.

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ackermann, R.T., Williams, J.W. Rational treatment choices for non-major depressions in primary care. J GEN INTERN MED 17, 293–301 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.10350.x

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.10350.x