Abstract

Study design:

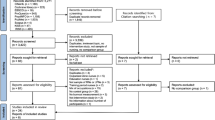

Cross-sectional and longitudinal direct observation of a constrained consensus-building process in nine consumer panels and three rehabilitation professional panels.

Objectives:

To illustrate differences among consumer and clinician preferences for the restoration of walking function based on severity of injury, time of injury and age of the individual.

Setting:

Regional Spinal Cord Center in Philadelphia, USA.

Methods:

Twelve panels (consumer and clinical) came to independent consensus using the features–resource trade-off game. The procedure involves trading imagined levels of independence (resources) across different functional items (features) at different stages of recovery.

Results:

Walking is given priority early in the game by eight out of nine consumer panels and by two out of three professional panels. The exception consumer panel (ISCI<50) moved walking later in the game, whereas the exception professional panel (rehRx) moved wheelchair early but walking much delayed. Bowel and Bladder was given primary importance in all panels.

Conclusions:

Walking is a high priority for recovery among consumers with spinal cord injury irrespective of severity of injury, time of injury and age at time of injury. Among professional staff, walking is also of high priority except in rehabilitation professionals.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Consumer preference and satisfaction are important and essential components of the current paradigm defined and described in the Long Range Plan of the National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research, US Department of Education.1 The United States requires rehabilitation facilities to document consumer satisfaction for certification;2 consumer input is also required for ‘service plans,’ which are tailored to specific individual needs. In the UK, a new clinical checklist, needs assessment checklist,3 is used as an outcome measure to ensure that rehabilitation services address the needs of the patient. This checklist has been found to be effective in rehabilitation program planning with positive correlations between goals set and those achieved. Active client involvement in the rehabilitation process enhances patient compliance and is a good predictor of a positive outcome.4

Spinal cord injury (SCI) presents a unique patient population to address consumer preference and the implications for rehabilitation planning. Although numerous studies have addressed the domains of quality of life among persons with SCI,5, 6, 7 only a few studies have directly queried people with SCI to indicate what specific improvements in function are most meaningful to each individual.8, 9, 10 From her survey, Anderson8 reported that regaining arm/hand function is of high priority to persons with quadriplegia, whereas sexual function is of high priority to persons with paraplegia; however bowel, bladder and walking are of equal importance. Utilizing retrospective review, both Donnelly9 and Estores10 reported that functional mobility is among the top goals for patients. Kilgore et al.11 reported that consumers' research priorities are focused on independence with mobility and ease of movement.

This study applies a forced consensus methodology, which compares walking function to other functions (features), to investigate recovery preferences of consumers following SCI. Stineman12 has developed a model to assess preferences for rehabilitation outcomes. Utilizing items from the functional independence measure (FIM),13 she introduced the features–resource trade-off game (FG) and recently reported a discrepancy between the ratings of imagined preferences for recovery of general dimensions of disability given by American consumers with disabilities and American clinicians. Using a modified version of the FG (MFG), Patrick14 has shown differences for mobility between American consumers and rehabilitation professional staff preferences for recovery. The objective of the current study is to apply this methodology to demonstrate consumer preference for the restoration of walking function based on the severity of the injury, the time of the injury (acutely injured versus those living with SCI over time) and the age of the individual. We hypothesize that consumers with SCI will express a preference for restoration of walking over most other functions (features) on the modified FIM (MFIM) and that consumer preference for restoration of walking will differ from clinicians.

Methods

A version of Stineman's FG, the MFG, which demonstrates consumer preference was applied to SCI. Spinal cord independence measure (SCIM)15 is currently recognized as a preferred global measure for assessment of clinical progress, while FIM has in the past been used and validated to measure consumer preference. The features game was originally developed and validated using the FIM, and has recently been used to measure consumer preference in SCI.12, 16

Six items of self-care, two items of sphincter control and six items of mobility comprised the MFIM, with a total of 14 items. Only the motor items of the FIM were utilized, as they correlate with the severity of neurological impairment and recovery. Motor FIM items are grouped into self-care (eating, grooming, bathing, dressing the upper and lower body, and toileting), sphincter management (bladder and bowel) and mobility (walking/wheelchair, stairs, and chair, tub and toilet transfer). The FIM was further modified by separating walking/wheelchair to allow selection between devices.

Walking preference was compared to other dimensions of MFIM as follows:

-

complete SCI (c-SCI) compared cross-sectionally to incomplete SCI (i-SCI-cross5y)

-

incomplete SCI at 1 year (i-SCI-long1y) compared longitudinally to (same patients over time) at 2 years (i-SCI-long2y) and 5 years (i-SCI-long5y) after injury; and cross-sectionally compared to (different patients at three time intervals) at 1 year (i-SCI-cross1y), 2 years (i-SCI-cross2y) and 5 years (i-SCI-cross5y) after injury

-

Incomplete SCI less than 50 years (i-SCI<50) compared to those greater than 50 at the time of injury (i-SCI>50)

-

SCI consumers compared to clinicians: acute care (aRx), rehabilitation (rehRx) and follow-up phases (fupRx), including physical and occupational therapists, nurses and physicians

SCI consumers identified through the Consumer Advisory Committee of the Regional SCI center were selected based on severity of injury, time from injury and age at the time of injury (all incomplete patients had the potential for walking); clinicians were also recruited from the Regional SCI Center.

This study involved the direct observation of a constrained consensus-building process in 12 panels over 5 years. Each panel was to have 5 members; however, due to attrition some panels had three members (always an uneven number) (see Table 1). The objective was to determine whether preferences of consumers differ from each other and from clinicians based on severity of injury, time from injury and age of individuals. The primary analysis was qualitative in nature; quantification using discrepancy scores was a tool to aid in comparing the qualitative differences among the panels.

Panelists were instructed to make moves such as ‘maximize personal and economic freedom.’ Before beginning the game, the notions of independence and care burden (societal costs) were described as they relate to the MFIM instrument.

The FG was developed to evaluate how values of people with disabilities and clinicians differed with respect to the relative value of being able to perform various functional activities. The features traded here were the 14 MFIM items. The game uses the nominal group process that is integrated with concepts from economic utility analysis; this process assures that each panelist has equal opportunity for input. The game is played on a large board with the 14 MFIM items listed down the left side of the board and 7 performance levels (1: total assistance; 2: maximal assistance; 3: moderate assistance; 4: minimal assistance; 5: supervision; 6: independence with device; 7: complete independence) listed across the top (see Ditunno et al.16).

Staff instructed the panelists and monitored and recorded data. Basic instructions included definitions of the 14 MFIM items and 7 performance levels, instructions and rationale for the nominal group process, a description of sequence of events, and statements of the guiding principle for selection of moves. To begin the game, panelists are each asked to imagine that they are unable to eat, groom, dress, control their bladder, walk, etc. The first panelist is asked to select the MFIM item he/she would want to begin to recover first. The game then involves a continuous two-step process of building imagined recovery patterns.

Step 1: the free movement phase

Each panelist is allowed one move forward (on any item of choice) until 14 moves are made, with no discussion.

Step 2: zero-sum exchange with individual discussions and voting

Each panelist makes one move forward at the expense of one back. This panelist provides support for the move and others comment. The panelist, who proposed the move, makes a closing statement and the panel votes. The move is accepted or rejected by majority vote.

Steps 1 and 2 are repeated until the five interim stages are defined.

Stage one is the starting point with a score of 14, indicating total dependence. Stages 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6 have scores of 28, 42, 56, 70 and 84, respectively. Stage 7 has a score of 98, indicating total independence.

Since panel members can ‘spend’ the 14 points in any way they chose, the functional states defining stages 2–6 differ for each panel. The decision to advance specific items multiple times at the expense of not moving other items illustrates the influence of individual preferences.

Raw data for each stage is illustrated in concentric pie charts. Thirty-five two-way sets of discrepancy scores were computed and organized into panel type comparisons (see Stineman,12 Ditunno16 for more detail). Cumulative discrepancy scores as well as cumulative item level discrepancy scores for each two-way panel comparison were calculated. A higher discrepancy score indicates greater disagreement, and a lower score suggests greater agreement.

Results

Graphical representation of the response patterns of the panels to the features game for the critical stages 3 and 4 are shown in Figures 1, 2, 3, 4, 5. In these pie charts, the 14 items (eating, Ea; grooming, Gr; bathing, Ba; dressing upper body, DU; dressing lower body, DL; toileting, To; bladder, Bl; bowel, Bo; chair/bed transfers, ChT; toilet transfers, ToT; tub transfers, TuT; walking, Wa; wheelchair, WC; stairs, St) are abbreviated around the periphery; concentric circles correspond to each of the seven FIM performance levels. The innermost circle signifies 1 or total dependence and the outer circle indicates 7 or total dependence.

Walking is given priority importance early in the game by all patient panels (i-SCI-cross1y, c-SCI, i-SCI-long1y, i-SCI-long2y, i-SCI-long5y, i-SCI-cross2y, i-SCI-cross5y and i-SCI>50) except i-SCI<50, while walking is given priority importance by both clinician panels, aRx and fupRx, except rehRx. By stage 4, all but two panels (i-SCI<50 and rehRx) have moved walking to a level 6 (modified independence with device) or 7 (complete independence). The i-SCI<50 delayed movement of walking to a high level until stage 5. The rehRx panel moved wheelchair to level 5 (supervision) at stage 3, and moved wheelchair to its maximum level by stage 4; moving walking only to level 4 (minimal assistance) at stage 4.

As expected, bowel and bladder are also given importance early in the game. By stage 3, most panels had moved bowel and bladder to level 5 (supervision), 6 (modified independence with device) or 7 (complete independence). By stage 5, all panels had moved bowel and bladder to level 6 or 7.

Item level discrepancies

Greatest agreement on items across all panels (small discrepancy scores with little variance) is seen in bladder management (scores range from 10 to 0) and bowel management (range 12–0). Greatest item differentials across panels (large scores and large variance) is seen in stairs (range 93–0), wheelchair (range 92–2) and toilet transfer (range 89–3).

Between panel discrepancies

Greatest agreement (smallest cumulative discrepancy scores at stage 6) between panels across all items and all stages is between i-SCI-long1y and i-SCI-long2y longitudinal panels. Greatest disagreement (largest cumulative discrepancy scores at stage 6) is between rehRx and i-SCI-cross1y, i-SCI-long1y, i-SCI-cross5y, i-SCI-long5y; and between fupRx and i-SCI-cross2y, i-SCI-cross5y.

Discussion

Our study confirms that for most consumer panels walking is a highly desired goal relative to other functions (features). Eight out of nine consumer panels moved walking to a high level (6–7) in the early stages. This supports our hypothesis that consumers with SCI express a preference for restoration of walking function over most other functions on the MFIM.

The professional panels aRx and fupRx moved walking similar to the patient panels with one exception. The rehRx moved wheelchair to level 5 at stage 3 and to level 6 at stage 4. When queried, the rehRx panel participants responded that in the current reimbursement environment, in the USA, of having to discharge patients early in their rehabilitation, it is necessary to focus first on wheelchair independence and plan for ambulation training as an outpatient. Other cultures treat consumers as inpatients until they plateau, and the features game research reflects this differential (see detailed discussion in Ditunno et al.16).

In this study, comparisons between panels (cumulative discrepancy scores) also demonstrated differences between professionals and consumers recovery preferences. It is apparent that as early as stage 3 rehRx moved wheelchair and not walking, and most other panels at this point have moved walking and not wheelchair. Thus the item discrepancy related to walk/wheelchair differential is also reflected between panels. One important note is that this study reports only results from one group of rehabilitation professionals in the United States. To adequately address this issue, it is important to design a multicenter study, and if this is a confirmatory and consistent finding, we must examine strategies for remedial system change. Perhaps we should begin to investigate a shift in treatment and research activities towards restoration of walking.

Our study shows that the greatest overall agreement across consumers and professionals is within the domain of sphincter control. Management of bowel and bladder is seen as paramount to independence. This is universally reported in the general literature14, 17, 18 and also in cross-cultural features game studies,16 demonstrating concurrent validation utilizing a new methodology.

Stairs is also an item that seems to reveal differences between consumer panels and professionals. ARx and rehRx tend to move stairs only at the later stages (5 and 6), as early in the recovery process stairs is not deemed a high priority item; fupRx move stairs consistently throughout the stages as do some consumer panels and this may reflect an attitude of reaching the greatest level of mobility independence within the community environment. Toilet transfer also shows item differences in particular between c-SCI and rehRx and may reflect that complete patients commonly use catheters and/or other means of bowel management.

Another interesting finding relates to the response shift of the longitudinal group. In years 1 and 2, walking, bowel and bladder were important, but the response pattern showed more variation than at year 5. At year 5, recovery preferences for walking, bowel and bladder were clearly more pronounced at the early stages. These results, however, are limited because we have longitudinal data for only one group, and further investigation examining the response shift of the same group of individuals over time is another interesting area for future study.

While survey research may sample large populations, it often loses specificity of results. The features resource trade-off game is a method that allows us to examine how panels of individuals sharing common situations vary in their feelings about relative value of different items of functional recovery. This study employs a rigorous approach to sampling consumer/staff preference and incorporates both a cross-sectional and longitudinal paradigm giving us the opportunity to measure preferences for recovery in panels of different individuals at different time points after injury as well as panels of the same individuals over time post injury. These preliminary findings will require confirmation in multiple centers and in differing situations. One possibility for further investigation would be to have two different game boards, one with only wheelchair and the other with only walking to determine the value of different mobility conditions (wheelchair or walking) relative to the other FIM items. Perhaps wheelchair mobility will be valued as less important than the other FIM items, whereas walking mobility will be valued to be just as important, if not more as the other items.

Lastly, this methodology can be used to gain consumer insight into future priorities for the development of clinical programs and research. These findings suggest that clinical programs and research directed at improving walking function should be given as high a priority as bowel and bladder functions.

References

National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research. Notice of final long-range plan for fiscal years 2005–2009. Federal Register 2006; 71: 8166–8200.

The Rehabilitation Accreditation Commission http://www.carf.org/consumer.aspx?Content=Content/ConsumerServices/cs03en.html&ID, Accessed July 26, 2005.

Kennedy P, Hamilton LR . The needs assessment checklist: a clinical approach to measuring outcome. Spinal Cord 1999; 37: 136–139.

Duff J, Evans MJ, Kennedy P . Goal planning: a retrospective audit of rehabilitation processes and outcome. Clin Rehabil 2004; 18: 275–286.

Tate DG, Kalpakjian CZA, Forchheimer MB . Quality of life in individuals with spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2002; 83 (Suppl 2): S18–S25.

Manns PJ, Chad KE . Components of quality of life for persons with a quadriplegic and paraplegic spinal cord injury. Qual health Res 2001; 11: 795–811.

Dijkers MPJM, Whiteneck G, El-Jaroudi R . Measures of social outcomes in disability research. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2000; 81 (Suppl 2): S63–S80.

Anderson K . Targeting recovery: priorities of the spinal cord-injured population. J Neurotrauma 2004; 21: 1371–1383.

Donnelly C, Eng JJ, Hall J, Alford L, Giachino R, Norton K et al. Client-centered assessment and the identification of meaningful treatment goals for individuals with a spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 2004; 42: 302–307.

Estores IM . The consumer's perspective and the professional literature: what do persons with spinal cord injury want? J Rehabil Res Dev 2003; 40: 93–98.

Kilgore KL, Scherer M, Bobblitt R, Dettloff J, Dombrowski DM, Godbold N et al. Neuroprosthesis consumers' forum: consumer priorities for research direction. JRRD 2001; 38: 655–660.

Stineman MG, Maislin G, Nosek M, Fiedler R, Granger CV . Comparing consumer and clinician values for alternative functional states: application of a new feature trade-off consensus-building tool. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1998; 79: 1522–1529.

Keith RA, Granger CV, Hamilton BB, Sherwin FS . The functional independence measure: a new tool for rehabilitation. Adv Clin Rehabil 1987; 1: 6–18.

Patrick M, Ditunno PL, Ditunno JF . A Comparison of spinal cord injury (SCI) consumers/staff preference for walking: a pilot study. J Spinal Cord Med 2003; 26: S41.

Catz A, Itzkovich M, Agranov E, Ring H, Tamir A . SCIM-spinal cord independence measure: a new disability scale for patients with spinal cord lesions. Spinal Cord 1997; 35: 850–856.

Ditunno PL, Patrick M, Stineman M, Morganti B, Townson AF, Ditunno JF . Cross-cultural differences in preference for recovery of mobility among spinal cord injury rehabilitation professionals. Spinal Cord 2006; 44: 567–575.

Glickman S, Kamm MA . Bowel dysfunction in spinal cord injury patients. Lancet 1996; 347: 1651–1653.

Hicken BL, Putzke JD, Richards JS . Bladder management and quality of life after spinal cord injury. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2001; 80: 916–922.

Acknowledgements

This material was based on work supported by the National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research, Office of Special Education and Rehabilitative Services, US Department of Education, grant no. H133N000023.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ditunno, P., Patrick, M., Stineman, M. et al. Who wants to walk? Preferences for recovery after SCI: a longitudinal and cross-sectional study. Spinal Cord 46, 500–506 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.sc.3102172

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.sc.3102172

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Assessing walking ability using a robotic gait trainer: opportunities and limitations of assist-as-needed control in spinal cord injury

Journal of NeuroEngineering and Rehabilitation (2023)

-

Exoskeleton-based training improves walking independence in incomplete spinal cord injury patients: results from a randomized controlled trial

Journal of NeuroEngineering and Rehabilitation (2023)

-

Utilization of overground exoskeleton gait training during inpatient rehabilitation: a descriptive analysis

Journal of NeuroEngineering and Rehabilitation (2023)

-

Performance of the Dutch clinical prediction rule for the ambulation outcome after spinal cord injury in a middle-income country clinical setting: an external validation study in the Thai retrospective cohort

Spinal Cord (2023)

-

Orthotic walking outcome of persons with motor complete low thoracic spinal cord injury—a retrospective study

Spinal Cord (2023)