Abstract

Study design:

Cross-sectional, survey.

Objectives:

To extend current theoretical models predicting life satisfaction post-spinal cord injury (SCI). Our primary model predicting life satisfaction as measured by the Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS) examined demographic characteristics, elements of the International Classification of Functioning and subjective and objective measures of health. A second model was developed to examine factors that are associated with successful community participation as measured by the Reintegration to Normal Living Index (RNL). In addition, the effects of psychological distress and chronic pain on life satisfaction and community participation were examined.

Setting:

Toronto Rehabilitation Institute, Spinal Cord Rehabilitation Program, Lyndhurst Centre.

Methods:

Prospective data collection via semi-structured telephone interview on an established SCI Canadian sample.

Results:

In predicting life satisfaction, our model accounted for 35.3% of the variance with demographic characteristics, objective and subjective health, and community participation significantly contributing to the model. In particular, psychological complications, current health rating and community participation were the only variables that made significant contributions in predicting life satisfaction. With regards to community participation, the presence of psychological complications and number of medical complications were associated with decreased reintegration. Increased time since injury onset, higher health ratings and being employed were positively related to RNL.

Conclusion:

It would appear that factors involving functional decline and aging are associated with lower participation but not life satisfaction. Further, models predicting quality of life should incorporate measures of psychological functioning.

Sponsorship:

Toronto Rehabilitation Institute

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Recent reports on spinal cord injury (SCI) trends indicate life expectancies are now comparable to those of able-bodied contemporaries.1 As people age, they experience a variety of physical limitations and declines in health brought on by typical aging, by years of having secondary health complications, pathological processes not related to the primary lesion (for example, heart disease) and by environmental factors (for example, cultural).2 This comprises an SCI person's ability to sustain independence and ability to participate in their communities at later stages in life.3 These changes have been shown to have an impact on life satisfaction, which is a subjective component of quality of life (QOL) assessing global functioning and circumstances.4 However, associations among QOL, aging, impairment and health have been contradictory,5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 highlighting the need for further investigation.

Consistent predictors of life satisfaction have been subjective perceptions of one's health and participation.11, 12, 13 As proposed by the World Health Organization (WHO), participation refers to the scope of social obstacles and opportunities, and is a main domain of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF). The other ICF domains include body functions and structures (the direct physical condition of the body) and activities (the full range of activities performed by an individual). Fuhrer14 consolidated studies reviewing the different WHO components, and found that only participation was consistently related to QOL.

In an attempt to examine all of the WHO components on life satisfaction, Pierce et al.11 created a predictive model incorporating all three domains and enhanced it by including self-perceived health. The strongest predictors were participation followed by self-perceived health. Although demographics, body function and structure, and activity were also significant, they did not explain a substantial proportion of the variance. A criticism of the model was the exclusion of objective health measures, which was excluded since it had not been shown scientifically to predict QOL. However, a potential barrier to social participation is impaired health.

Richards et al.13 recognized the potential impact of health complications, and focused on factors impacting access to the environment as being potential predictors of life satisfaction. They defined access to the environment as all physical, geographic and sociocultural characteristics that pertain to a person's living situation. In addition, measures of objective health (that is, total number of complications) were also assessed. The results indicated that access to the environment explained as much variance as physical function and occupation. Health complications, however, did not significantly contribute to the overall life satisfaction model.

Using a similar model and data set, Putzke et al.12 also found mobility, and perceived health status were uniquely related to life satisfaction. Univariate analyses revealed that an increased number of health complications and re-hospitalizations significantly correlated with life satisfaction. Congruent with previous findings, these variables did not significantly contribute to the overall regression model. Although both Richards et al.13 and Putzke et al.12 utilized samples with relatively short injury durations, their findings demonstrate the complex relationship between objective and subjective health and their collective impact on QOL.

A missing component of these earlier models is psychological functioning. Depressive disorders are a common problem associated with SCI, and have been found to be predictive of QOL.15 With regards to aging, Krause et al.16 found that individuals who were older at injury, beginning with ages of 30–39 years, were at greater risk for both clinically significant symptoms and probable major depression. The reason being that older individuals may have a harder time adapting to their SCI, because they may be more set in their ways.16 Similar findings have been found highlighting the unique and important relationship depressive symptoms with QOL.17 It is clear that some measure of psychological functioning needs to be included in models predicting life satisfaction to ascertain how these two variables relate to one another.

Another significant complication believed to impact on QOL is chronic pain. Although pain has been consistently demonstrated to have a negative relationship with QOL, it has not been found to be a significant predictor of life satisfaction.18 Further work is needed on elucidating the influence of pain on life satisfaction.

The primary objective of the current study was to extend current theoretical models predicting life satisfaction in persons with SCI. In our life satisfaction model, we examined demographics, elements of the ICF, and objective and subjective measures of health. We hypothesized that: (1) older persons with SCI and a longer duration of injury would report lower life satisfaction due to lower community participation and (2) persons experiencing chronic pain, psychological complications, and a greater number of health complications would report lower satisfaction with life. A model predicting community participation was also conducted to ascertain the influence of different factors on participation and, thereby, clarify findings from the life satisfaction model.

Materials and methods

Participants

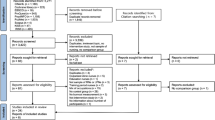

A total of 2839 potential participants were identified from a Long Term Follow-Up database, and the hospital's health records department. Five hundred and sixty-four had passed away, 146 declined participation and 1302 could not be located. An additional 46 participants with peripheral nerve, immunological, progressive disease (for example, Guillan–Barré Syndrome) were also excluded. See Table 1 for the demographic and impairment characteristics of the final sample of 781 participants. Table 2 provides a broad overview of the types of health complications reported by the sample.

At the time of injury, the mean age was 37.42 (s.d.=16.34) years and the mode was 26. The majority 630 (80.7%) had a traumatic injury and 148 (19.7%) had a non-traumatic injury. Non-traumatic etiologies included were infection, tumour, degenerative conditions, and other etiologies with a sudden onset.

We certify that all applicable institutional and governmental regulations concerning the ethical use of human volunteers were followed during the course of this research.

Impairment

Self-reported impairment was collapsed into four groups: complete quadriplegia, incomplete quadriplegia, complete paraplegia and incomplete paraplegia.

Objective health status

The health complications of interest were psychological complications (depression, psychological distress and substance abuse) and pain (chronic pain, shoulder pain, arthritis/joint pain). Variables were dummy-coded with a 0 representing absence of a complication, and 1 representing the presence of a complication. In addition, a total number of medical complications variable was created as the combination of the complications just listed, and any of the following experienced in the past year: pressure ulcers, bladder infections, bladder/kidney problems, bowel problems, spasticity, heart problems, high blood pressure, autonomic dysreflexia, respiratory complications, neurologic deterioration, fracture and heterotopic ossification.

Subjective health status

A 10-point numeric scale was used to assess health status, with 1 being ‘poor’ and 10 being ‘excellent’. Capturing perceived health status provides the opportunity to explore some of the variance associated with measures of life satisfaction.

Reintegration to normal living (RNL) index19

The RNL Index is a measure of community reintegration, which covers areas such as participation in recreational and social activities, movement within the community and the degree of comfort the individual has in his/her role in the family and with other relationships. Each item is rated using a three-point categorical scale, which has been validated for collection over the telephone. The internal consistency of the RNL for a patient's sample is 0.90 and for health professionals is 0.92.19

Satisfaction with life scale (SWLS)4

The SWLS is a 5-item scale that assesses people's satisfaction with their life as a whole. A total score is obtained by adding all the items with higher scores reflecting more life satisfaction. The SWLS can be administered over the telephone, and has a test–retest reliability of 0.82 over a 2-month interval, and has an internal consistency reliability of 0.87.4

Procedure

All participants were former patients of Ontario spinal cord rehabilitation hospital. After an information letter was mailed to each potential participant, they were telephoned to obtain informed consent. Telephone interviews were conducted using a structured questionnaire collecting data on sociodemographics, mortality, injury characteristics, health status, secondary health complications, mobility, RNL and SWLS. Interviewers received formal training. Each interview lasted for approximately 15 min. Randomly selected questionnaires were reviewed to assess reliability and consistency of the data by cross-referencing injury characteristics with health records. Missing data points regarding date of birth, date of injury onset and impairment were completed by reviewing hospital charts.

Analyses

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the demographic and impairment characteristics of the sample. Certain demographic variables were dummy-coded into the following groups: (1) marital status (married vs single; ’married’ included persons who were common-law; 'single’ included people who were never married, divorced or widowers); (2) education (post-secondary vs no post-secondary); (3) employment (employed vs unemployed; ’employed’ included students and volunteers); (4) living situation (living with someone vs living alone). Hierarchical multiple regression was used to predict life satisfaction. Demographics were entered into the first block (age, sex, education, marital status, employment status and living situation), followed by impairment (impairment group, duration of injury and etiology), objective health (psychological complications, chronic pain and total number of complications), subjective health (self-health rating) and participation (RNL). Similarly, hierarchical multiple regression was used to predict participation. For this model, demographics were entered into the first block, followed by impairment, objective health and subjective health. Independent samples t-tests were conducted to ascertain differences between participants with and without psychological complications and chronic pain. Finally, Pearson correlation coefficients were conducted to examine associations between age and injury duration with scores on the SWLS and RNL.

Results

With regard to the regression model predicting SWLS, the addition of each set of variables produced a significant increase in the amount of variance explained except for impairment (see Table 3). The final regression model explained 35.3% of the variance and was statistically significant (P<0.0005).

An examination of the weights assigned to the predictor variables in the final analysis reveals that only three of the predictor variables made unique, statistically significant contributions to the predictive accuracy (see Table 4). Psychological complications had a negative weighting, indicating that the presence of psychological complications was associated with lower satisfaction with life. Current health rating and RNL both had positive weights indicating that better health and better reintegration are associated with increased life satisfaction.

The final regression analysis predicting participation explained 34.0% of the variance (see Table 5). The addition of each set of predictor variables produced a statistically significant improvement in the predictive accuracy of the regression analysis.

Five of the predictor variables made statistically significant, unique contributions to the final analysis (see Table 6). Both psychological complications and total number of complications were negatively weighted, indicating that the presence of psychological complications or an increasing number of medical complications were associated with decreased community participation. Increased time since injury, higher health ratings and being employed were positively related to RNL.

Chronic pain and psychological distress on QOL

The mean SWLS and RNL scores were compared for those who reported no or minor chronic pain against the scores of those who reported moderate to severe chronic pain (see Table 7). Those with chronic pain had significantly lower scores on the SWLS (t(778)=5.879, P<0.0005) and on the RNL (t (735.20)=4.406, P<0.0005). Similarly, those who had psychological complications had significantly lower scores on the SWLS (t(778)=10.020, P<0.0005) and on the RNL (t (675.32)=9.563, P<0.0005).

Age, duration of injury and QOL

Pearson correlation coefficients revealed that age was negatively correlated with the RNL (r=−0.106, d.f.=780, P<0.0005) and negatively correlated with the SWLS (r=−0.019, d.f.=780, P=0.590), although this relationship was not significant. Conversely, injury duration was positively correlated with the RNL (r=0.187, d.f.=780, P<0.0005) and with the SWLS (r=0.127, d.f.=780, P<0.0005).

Discussion

The results of this study support previous findings regarding QOL after SCI, but are unique in those few studies that have been done on such a large Canadian sample. In predicting life satisfaction, our model accounted for 35% of the variance with demographics, objective and subjective health, with participation being significant. Similar to previous studies, impairment was not significant. In particular, psychological complications, self-perceived health and participation were the only significant contributors. Hence, persons who had psychological complications, perceptions of poor health and lower RNL scores were more likely to have lower life satisfaction.

Although pain was not significant, univariate analyses demonstrated that those with moderate to high levels of pain had significantly lower life satisfaction than those without pain. As expected, persons with psychological complications also had lower life satisfaction than those with none.

Our model predicting community participation accounted for 34% of the variance. Demographics, impairment, objective and subjective health were found to be significant contributors to the model. In particular, employment status, injury duration, psychological complications, number of complications and perceived health were significant. As hypothesized, it would appear that the factors associated with lower community participation are those involving functional decline and aging. Hence, persons who had been injured longer, who were unable to work, who had more health complications, who had a psychological complication, and who rated their overall health as low were less likely to participate in their communities. Unlike the life satisfaction model, the number of complications were significant in predicting participation, suggesting that issues associated with aging (that is, poor health) may be more influential on different aspects of QOL.

In general, the findings highlight the strong relationship between psychological functioning and QOL. Although the direction of this relationship cannot be confirmed due to the nature of the analyses, there is evidence in the literature clearly showing that poor psychological functioning negatively impacts QOL.15, 16, 17 Regardless of direction of association, there is a need to provide stronger service support on psychological health given its impact on the SCI population. Community-based services or outpatient hospital programs may be suited to addressing this need.

A number of limitations were associated with this study. First, the data set was intended to be a minimum data set, low in administrative burden in order to track general health trends of the Canadian SCI community. Second, self-reported physical and psychological health may not accurately reflect the complexity or severity of the reported condition. Future studies should include standardized measures of health, especially for psychological functioning. Finally, standardized measures of impairment (for example, American Spinal Injury Association Impairment Scale) were also unavailable.

We must also consider the possibility of the two group theory of long-term SCI survivors.20 One group comprises persons who age relatively well with few health complications, and the other group are people with higher levels of lesion who experience multiple health and increased disability-related problems. Hence, our contact method may have inadvertently excluded those who were too sick to participate. It should be noted that some of the participants from our sample pool were injured several decades ago. As such, our inability to contact approximately 50% of previous patients is likely due to them moving away since their initial injury, death or no longer interacting with the hospital.

Despite these limitations, this study presents the largest Canadian SCI data set, and contributes to our understanding of QOL in this population. The findings indicate that both the SWLS and RNL tap into different components of QOL, and may justify current recommendations being put forth by international groups on how to assess QOL after SCI.

References

DeVivo MJ, Krause JS, Lammertse DP . Recent trends in mortality and causes of death among persons with spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1999; 80: 1411–1419.

McColl MA, Charlifue S, Glass C, Savic G, Meehan M . International differences in ageing and spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 2002; 40: 128–136.

Thompson L, Yakura J . Aging related functional changes in persons with spinal cord injury. Top Spinal Cord Inj Rehabil 2001; 6: 69–82.

Pavot W, Diener E . Review of the satisfaction with life scale. Psychol Assess 1993; 5: 164–172.

McColl MA . Expectations of health independence, and quality of life among aging spinal cord-injured adults. Assist Technol 2002; 11: 130–136.

Westgren N, Levi R . Quality of life and traumatic spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1998; 79: 1433–1439.

Dijkers MP . Correlates of life satisfaction among persons with spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1999; 80: 867–876.

Kemp BJ, Ettelson D . Quality of life while living and aging with a spinal cord injury and other impairments. Top Spinal Cord Inj Rehabil 2001; 6: 116–127.

Eisenberg MG, Saltz CC . Quality of life among aging spinal cord injured persons: long term rehabilitation outcomes. Paraplegia 1991; 29: 8–91.

McColl MA, Stirling P, Walker J, Corey P, Wilkins R . Expectations of independence and life satisfaction among ageing spinal cord injured adults. Disabil Rehabil 1999; 21: 231–240.

Pierce CA, Richards JS, Gordon W, Tate D . Life satisfaction following spinal cord injury and the WHO model of functioning and disability. Spinal Cord Inj Psychosocial Process 1999; 12: 24–127.

Putzke JD, Richards JS, Hicken BL, DeVivo MJ . Predictors of life satisfaction: a spinal cord injury cohort study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2002; 83: 555–561.

Richards JS, Bombardier CH, Tate D, Dijkers M, Gordon W, Shewchuk R et al. Access to the environment and life satisfaction after spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1999; 80: 1501–1506.

Fuhrer MJ . The subjective well-being of people with spinal cord injury: relationships to impairment, disability, and handicap. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 1996; 73: 358–364.

McColl MA, Rosenthal C . A model of resource needs of aging spinal cord injured men. Paraplegia 1994; 32: 261–270.

Krause JS, Kemp B, Coker J . Depression after spinal cord injury: relation to gender, ethnicity, aging, and socioeconomic indicators. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2000; 81: 1099–1109.

Post MWM, de Witte LP, van Asbeck FWA, van Dijk AJ, Schrijvers AJP . Predictors of health status and life satisfaction. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1998; 79: 395–401.

Charlifue SW, Lammertse DP, Adkins RH . Aging with spinal cord injury: changes in selected health indices and life satisfaction. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2004; 85: 1848–1853.

Wood-Dauphinee SL, Opzoomer MA, Williams JI, Marchand B, Spitzer WO . Assessment of global function: the reintegration to normal living index. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1988; 69: 583–590.

McColl MA, Arnold R, Charlifue S, Glass C, Savic G, Frankel H . Aging, spinal cord injury, and quality of life: structural relationships. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2003; 84: 1137–1144.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the support of Toronto Rehabilitation Institute, which receives funding under the Provincial Rehabilitation Research Program from the Ministry of Health and Long Term Care in Ontario. We thank Kieva Richards, BSc, Michael Johnson, BA, Jennifer Greves, Dipl., Chad Greene, BA, and Andrea Brown, BSc, for their work on the project. We also thank the study participants for their time and support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tonack, M., Hitzig, S., Craven, B. et al. Predicting life satisfaction after spinal cord injury in a Canadian sample. Spinal Cord 46, 380–385 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.sc.3102088

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.sc.3102088

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Quality of life after traumatic thoracolumbar spinal cord injury: a North Indian perspective

Spinal Cord (2023)

-

Life satisfaction 18 months and 10 years following spinal cord injury: results from a New Zealand prospective cohort study

Quality of Life Research (2023)

-

Satisfaction with life, health and well-being: comparison between non-traumatic spinal cord dysfunction, traumatic spinal cord injury and Australian norms

Spinal Cord Series and Cases (2019)

-

Development of a Self-Management App for People with Spinal Cord Injury

Journal of Medical Systems (2019)

-

Work and wellbeing-related consequences of different return-to-work pathways of persons with spinal cord injury living in Switzerland

Spinal Cord (2018)