Abstract

Study design: Multicentered follow-up with centralized data collection based on retrospective study.

Objectives: To assess the outcome in a population of patients with spinal cord injury (SCI). The assessed outcomes are mortality, state of health, occupation, mobility, autonomy, social and partner relationships, quality of life (QoL), with the identification of any relation between results and demographic–clinical data.

Setting: Two rehabilitation centers (Udine and Trevi) and a Spinal Injuries Unit (Torino).

Methods: A total of 251 patients with SCI discharged after first hospitalization from rehabilitation facilities between 1989 and 1994 were enrolled. A questionnaire was administered by telephone.

Results: During the time between discharge and follow-up, 25 out of the 251 patients had died, yielding a mortality rate of 9.96%. A total of 80 patients did not give their consent. The 146 patients' mean interval from discharge from the rehabilitation facility was 6 years. At least 25% has been hospitalized again. The descriptive analysis also shows that 29.5% of patients were working, 48.6% were able to drive, 63.7% would leave their home alone, 61% would leave home every day, 63% reported of a change in their relationships, 48.6% were happy with their love lives. Significant correlations have emerged between certain items and age: those who had a job, who could drive, were more autonomous and had a higher QoL are generally younger. Level of injury appear to be only associated with the degree of autonomy, which seems to be inferior for tetraplegic subjects. The injury's completeness and etiology do not exhibit any correlation. QoL is associated with a number of items: a higher QoL is linked to the possibility to work, especially if it is a paid job, to the ability to drive, to a good degree of autonomy, to a lack of change in the social and partner relationships, and to a satisfactory love life.

Conclusion: At 6 years after discharge from rehabilitations, the effects of trauma on work and social and partner relationships, domains correlated with autonomy and QoL, are evident. Further investigation by means of a prospective study over the years are therefore necessary.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The number of studies analyzing the quality of life (QoL) of patients with spinal cord injury (SCI) is increasing, because of the decrease of the mortality rate observed in recent years, and the corresponding increase of life expectancy. The increased survival can explain the recent interest within medicine in assessing QoL after SCI. De Vivo et al1 have analyzed the mortality of the past 20 years, by comparing a group of patients who had a SCI between 1973 and 1977 with a group of patients who had a SCI between 1993 and 1998. They observed a 67% decrease in the mortality odds in the first year after injury. An equally significant mortality reduction and an increase of life expectancy have also been demonstrated by other studies, carried out by Hartkopp et al2 and by Yeo et al.3 The factors which have an impact on survival, as identified by McColl et al4 and in other studies,5,6 are age at the time of injury and the injury's level and completeness. This has promoted interest in the international community about these patients' morbidity, and QoL in time.

There are many different aspects to consider when dealing with patients with SCI, which cover different domains in the literature, including clinical, psychological, social and relational, occupational, and environmental issues, focusing both on the macroeffects, and on more specific consequences.

Many studies on SCI concern an extremely complex scope that comprises many of the above-mentioned aspects, that is, the QoL. As Dijkers7 points out in a study on a population of over 2000 spinal cord-injured patients, this parameter is associated with various factors, such as gender, years elapsed since the injury, degree of mobility, occupation, and level of social integration. In spite of these variables, however, all patients experience a ‘trauma’ which is not limited to the episode of the injury in itself, but rather consists in a full rearrangement involving not only body function but also the individual's expectations, plans, relationships, and the external environment. Thus, both the QoL and the health of these patients are influenced by a variety of factors which no study could fully cover. However, any research can contribute to broaden the knowledge about this condition. Studies have been carried out on social reintegration,8,9,10 on employment,11,12,13,14 on mobility,15,16,17 on psychological implications,18 on the relationship with a partner,19,20 on parenthood,21,22 on the use of time,23 on sports.24 In this work, we have decided to deal with some of these fields surveying a group of patients a long time after the injury, in order to add an Italian perspective to the international debate on this issue. We also aim to determine if, and how, specific conditions correlate with one another, as well as with specific demographic and clinical data. Among the possible areas of interest, we have selected those which have received greatest attention in the literature: state of health, occupation, mobility, autonomy, social and partner relationships, and QoL.

Methods

Participants

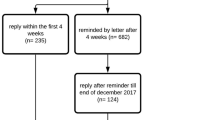

The inclusion criteria of this retrospective study were as follows: hospitalization date between 1989 and 1994 in a Spinal Injuries Unit and in two Italian intensive rehabilitation centers; diagnosis of SCI of any cause; first rehabilitative hospitalization. A total of 380 patients were enrolled. A retrospective research on clinical records identified the addresses of 275 patients, 24 of whom could not be contacted because they had relocated. Out of the 251 patients who were contacted, 25 had died and 80 did not give their consent to the follow-up study. The questionnaires were thus administered to 146 individuals.

Procedure

Multicentered follow-up with centralized data collection based on a retrospective study. Patients were administered a questionnaire by telephone, containing the items shown in Table 1.

The questionnaire is made up of 15 closed questions and two analogue scales. The two evaluation scales from 0 to 10 measure the two ordinal variables: autonomy and QoL. Two psychologists were in charge of the questionnaire's administration.

Statistical analysis

For univariate analysis, correlation indices (Spearman's ρ), the χ2-, Fisher's F- or Student's t-tests and the odds ratio were used, with relative confidence intervals.

Results

Descriptive analysis

Mortality calculated on the 251 participants was 9.96% (25 deaths). All other data were calculated on the 146 responders.

The population was made up of 104 (71.2%) males and 42 (28.8%) females. Mean age was 37.8 years (median age=36; SD=14.9). The mean interval from discharge was 6.1 years (range 3–10). In all, 109 injuries (74.7%) were of traumatic onset and 37 (25.3%) of nontraumatic onset.

The group of patients, of whom 53 (36.3%) had cervical injury and 93 (63.7%) had thoracolumbar injury, was classified at discharge using the Frankel Scale as follows: A, 44.6%; B, 2.7%; C, 13%; D, 39.7%.

Concerning state of health, 25.3% of responders had been hospitalized at least once in the past year, most frequently for urologic problems (22.9%), spasticity (11.4%), and rehabilitation treatment (11.4%). Concerning bladder function, 41.8% had voluntary urination (spontaneous or stimulated), 34.2% used intermittent self-catheterization, and the remaining 17.8% did not enjoy full autonomy.

The item on occupation shows that 29.5% was employed (Figure 1); of whom 35.6% reported to have changed jobs. In total, 35.8% of individuals worked a paid full-time job, 24.5% worked part-time, and 35.8% held a job with no remuneration. The most common sources for financial support were one's pension and family. As for education, 24% had completed primary school, 31.5% had a secondary school diploma, 39% had a highschool degree, and 3.4% had a college degree; 2.1% had no education.

The two items on mobility show that 51.4% of responders did not drive a car, and that 61% left home on a daily basis.

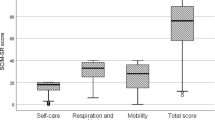

Concerning autonomy, 35.6% could leave home only with assistance, and the average autonomy score, assessed as an ordinal variable with a 0–10 scale, was 6.5.

Regarding social and partner relationships, we asked if there was a change in these relationships and 63% of responders answered in the affirmative (in terms of: detachment, 32.9%; more careful assessment of one's friendships, 13.4%; higher awareness of one's feelings, 12.2%; disruption of an important bond, 6.1%; overprotective family members, 3.7%). As for living conditions, 89.8% lived with their families, 5.5% lived alone, and 2.1% lived in an institution. The investigation on satisfaction with partner relationships revealed that 34.2% was not satisfied, 48.6% was satisfied, while 17.1% did not answer.

The mean score for QoL, recorded as an ordinal variable with the 0–10 evaluation scale, was 6.5.

Univariate analysis

Univariate analysis revealed significant correlations between demographic–clinical data and certain items, as well as among different items, both within the same area, and across different areas.

Occupation correlates with age, that is, those who worked or studied were in average younger than those who did not (30.4 versus 42.8; P<0.000 l). A significant correlation also exists between two items in the occupation area: the percentage of those who worked or studied was greater among those with higher education.

The item on driving is correlated to demographic–clinical characteristics such as: age (the mean age of those who could drive is 32.8 versus 42.8 of those who did not; P<0.0001), gender (56.7% males versus 28.6% females; OR=3.28, CI 1.42–7.66), etiology (54.1% traumatic versus 32.4% nontraumatic; OR=2.46, CI 1.05–5.81), level of injury (55.9% paraplegic versus 35.8% tetraplegic; OR=2.27, CI 1.07–4.83).

The item on autonomy as an ordinal variable inversely correlates with age (Spearman's ρ=−0.33), that is, the score decreases as age increases. A correlation has also been found with the injury level (P<0.0001): the mean autonomy score was 7.2 for paraplegics and 5.2 for tetraplegics. The ordinal variable also correlates with the item on driving (P<0.0001): the mean score was 7.6 for those who could drive and 5.3 for those who did not. A significant correlation was observed between the two items of this area (P<0.0001): the mean autonomy score was 7.2 for those who were able to leave home independently and 5.1 for those who did not.

The items concerning social and partner relationships do not correlate significantly with demographic–clinical data. A correlation instead exists between two items of the same area: 84% of those who reported a change in their relationships were not satisfied (OR=3.41, CI 1.02–14.62), and 53.6% of them were happy with their love life (OR=0.25, CI 0.1–0.65).

The QoL ordinal variable exhibits various significant correlations (see Table 2). Correlations with demographic–clinical data concern age, as age increases the score on the 10-point scale decreases (Spearman's ρ=−0.43). No significant correlation has been found with the level and completeness of the injury.

Moreover, QoL correlates with two items on employment (current occupation and salary): the QoL is higher for those who studied or worked, compared with those who did not (7.1 versus 5.96; P<0.0045), especially if they worked a paid job (part-time workers 8.2, full-time workers 7.3, volunteer workers 6.5; P<0.004). The correlation with the item on driving is significant (P<0.0006): the mean QoL score was 7.3 for those who could drive versus 5.7 for those who did not. QoL furthermore correlates with both items on autonomy (ordinal variable and need of assistance): the ordinal variable correlates directly (Spearman's ρ=0.48), those who could leave home alone had a mean score of 7.2 versus 5 for those who did not (P<0.0001). Significant correlations also exist with two items on social and partner relationships (change in relationships and degree of satisfaction in love life): the mean QoL score of those who report of partial or total changes in relationships is lower than that of those who claimed no changes (5.6 and 6.8 versus 7.1; P<0.003); the QoL mean score is higher for those patients who declared they were satisfied with their love life (7.2) compared to those who were not satisfied because of a lack of encounter opportunities (6.3), because of physical limitations (5) or both (5); P<0.0004.

Discussion

The analysis of the data and of the correlations has highlighted particularly problematic areas of outcome for a population of patients with SCI. The observed population turned out to be quite homogeneous, as the univariate analysis of the sample according to the trauma's etiology, and to the injury's level and completeness, has not significantly influenced the data: etiology only correlates with the item on driving; injury level only correlates with the item on driving and with the ‘autonomy’ variable; injury completeness does not exhibit any significant correlation.

Findings of the item on current occupation show an over 50% unemployment rate among patients with SCI, and some of those who declared to hold a job were not paid workers. Such findings are in line with the trend revealed by other studies: Conroy and McKenna14 have investigated the occupational outcome in a population of spinal cord-injured individuals with a mean period of 7 years after the injury. They found that, although 67% claimed they held a job after the injury, only 44% did actually get paid. Tomassen and van Asbeck12 found that only 37% of the patients with SCI they surveyed were gainfully employed after the injury. In a study by Lotta et al,8 on a group of patients discharged from a rehabilitation center and interviewed after at least 6 months, the employment rate drops from 66% before the injury to 28% after the injury; also in this case, almost half of the employed individuals (42.9%) are not paid workers. These data show that the occupation variable is not an indication for economic independence; in our work, like in other studies,8 the most frequent sources for financial support for Italian patients are found to be pension and family.

The correlation revealed by our work between current occupation and factors such as age and education has also been found by Krause et al13 and by Conroy and McKenna.14 These authors investigated predictors of employment after SCI, and they found a higher employment rate among younger and more educated patients. Age has been shown to be a predictor for the occupation outcome also by Taricco et al.25 It can be hypothesized that the types of job most suitable for patients with SCI will require lower physical intensity, and will mostly imply intellectual work and the ability to acquire new skills. The work by Tomassen et al12 on predictors of return to work after injury confirms this hypothesis. The survey of patients who were working at the time of the injury showed the main factors associated with a higher employment rate to be the patient's age and educational level, and the lower physical intensity of work preinjury. The QoL, which our study has shown to be correlated with occupation, has been examined by Wehman et al11 as a variable associated with work satisfaction in employed and unemployed persons with SCI.

Our results on mobility coincide with those found by other authors. Concerning car driving, Lotta et al found the percentage of patients who drive to be 46%. This percentage, lower than 50%, is relevant if the ability to drive is linked to autonomy, considered by other authors to be an important factor for work access and for taking part in social activities. Just like in our study, Kiyono et al26 also found a correlation between driving and age and level of injury.

We also found significant results in the area concerning social and partner relationships. Satisfaction in love life is particularly linked to a better QoL, as also shown in the work by Kreuter et al,20 where QoL appeared significantly lower for singles compared to those who had a partner. The importance of a meaningful relationship is also highlighted in our work by data on change in relationships; in fact, the presence of change, associated with a lower QoL, mainly translates into a detachment/disruption of bonds. Other studies on living as a couple have found that the greatest difficulties affect relationships which began before the injury,27 with a divorce rate ranging from 8 to 48%.28

QoL is a complex variable, and it is hard to define; hence, the utilization of different evaluation tools in different studies, as pointed out in a review by Hallin et al.29 In our work an analogic scale was used, which according to Hallin was also applied in studies by Vaidyananthan et al30 and Stensman.31 According to our method, QoL appears to be correlated to various factors: both to demographic–clinical data, and to various circumstances relating to employment, relationships, autonomy, and mobility. QoL is higher for younger individuals, for those who are employed (especially if they get paid) and those who feel more autonomous and independent, for those who can drive, those who report no change in their relationships, and those who are happy with their love life. The absence of a significant correlation between QoL and injury level, also pointed out by other authors, is interesting. Manns and Chad,32 studying the relationship between QoL, handicap, and physical activities in patients with SCI reported that subjective perceptions of QoL are not correlated with the level of injury. Westgren and Levi,33 who investigated QoL in a population of patients with traumatic SCI, observed no differences among complete paraplegic, incomplete paraplegic, complete tetraplegic, and incomplete tetraplegic individuals. Dijkers7 instead found a significant correlation between life satisfaction and level of injury, but not between satisfaction and completeness of injury.

Some authors noted the influence of time on QoL satisfaction, thus hypothesizing an adaptation process. In the study of Westgren and Levi,33 QoL appears higher for people whose injuries were older, whereas no difference emerged among QoL scores recorded immediately after injury – 1 month after discharge – and 6 months after discharge, as shown by Kennedy and Rogers.34 Our data can therefore be compared with data recorded after a sufficient time from the injury to allow for the hypothesized adaptation process to occur. It would be interesting to assess how a patient's perception of his/her life quality changes over time.

In conclusion, the effects of SCI on the areas described above (social and partner relationships, and QoL) are evident but also difficult to quantify, considering the importance of subjective variables. Since a longer time is necessary to achieve a full rearrangement in such areas, it can also be hypothesized that improvement measures are only taken in a later phase. Moreover, considering the difficulty of the evaluation of subjective variables strongly related to the time of evaluation itself, the effects of improvement measures should be assessed through the years with regular follow-up.

References

DeVivo MJ, Krause JS, Lammertse DP . Recent trends in mortality and causes of death among persons with spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1999; 80: 1411–1419.

Hartkopp A, Bronnum-Hansen H, Seidenschnur AM, Biering-Sorensen F . Survival and cause of death after traumatic spinal cord injury. A long-term epidemiological survey from Denmark. Spinal Cord 1997; 35: 76–85.

Yeo JD et al. Mortality following spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 1998; 36: 329–336.

McColl MA et al. Expectations of life and health among spinal cord injured adults. Spinal Cord 1997; 35: 818–828.

Frankel HL et al. Long-term survival in spinal cord injury: a fifty year investigation. Spinal Cord 1998; 36: 266–274.

Samsa GP, Patrick CH, Feussner JR . Long-term survival of veterans with traumatic spinal cord injury. Arch Neurol 1993; 50: 909–914.

Dijkers M . Correlates of life satisfaction among persons with spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1999; 80: 867–876.

Lotta S et al. Family, vocational and social reintegration of spinal cord injured patients following discharge from a rehabilitation centre. Eur Medicophys 1999; 35: 49–59.

Richards JS et al. Access to environment and life satisfaction after spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1999; 80: 1501–1506.

Noreau L, Fougeyrollas P . Long-term consequences of spinal cord injury on social participation: the occurrence of handicap situations. Disabil Rehabil 2000; 22: 170–180.

Wehman P et al. Employment satisfaction of individuals with spinal cord injury. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2000; 79: 161–169.

Tomassen CD, Post MWM, van Asbeck FWA . Return to work after spinal cord injury. Spinal cord 2000; 38: 51–55.

Krause JS et al. Employment after spinal cord injury: an analysis of cases from the model spinal cord injury systems. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1999; 80: 1492–1500.

Conroy L, McKenna K . Vocational outcome following spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 1999; 37: 624–633.

Craig A, Hancock K, Dickson H . Improving the long-term adjustment of spinal cord injured persons. Spinal cord 1999; 37: 345–350.

Dijkers M, Yavuzer G . Short version of the telephone motor functional independence measure for use with persons with spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1999; 80: 1477–1484.

Nyland J et al. Preserving transfer independence among individuals with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 2000; 38: 649–657.

Scivoletto G, Petrelli A, Di Lucente L, Castellano V . Psychological investigation of spinal cord injury patients. Spinal Cord 1997; 35: 516–520.

Yim SY et al. Quality of marital life in Korean spinal cord injury patients. Spinal Cord 1998; 36: 826–831.

Kreuter M, Sullivan M, Dahllof AG, Siosteen A . Partner relationships, functioning, mood and global quality of life in persons with spinal cord injury and traumatic brain injury. Spinal Cord 1998; 36: 252–261.

Westgren N, Levi R . Motherhood after traumatic spinal cord injury. Paraplegia 1994; 32: 517–523.

Nelson AL . Patients' perspectives of a spinal cord injury unit. SCI Nurs 1990; 7: 44–63.

Pentland W, Harvey AS, Smith T, Walker J . The impact of spinal cord injury on men's time use. Spinal Cord 1999; 37: 786–792.

Tasiemski T, Bergstrom E, Savic G, Gardner BP . Sport, recreation and employment satisfaction of individuals with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 2000; 38: 173–184.

Taricco M et al. The social and vocational outcome of spinal cord injury patients. Paraplegia 1992; 30: 214–219.

Kiyono Y et al. Car-driving abilities of people with tetrapelgia. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 200l; 82: 1387–1392.

Ville I, Ravaud JF . Subjective well-being and severe motor impairments: the Tetrafigap survey on the long-term outcome of tetraplegic spinal cord injured persons. Soc Sci Med 2001; 52: 369–384.

Kreuter M . Spinal cord injury and partner relationships. Spinal Cord 2000; 38: 2–6.

Hallin P, Sullivan M, Kreuter M . Spinal cord injury and quality of life measures: a review of instrument psycometric quality. Spinal Cord 2000; 38: 509–523.

Vaidyananthan S et al. Effect of intermittent urethral catheterization and oxybutynin bladder instillation on urinary continence status and quality of life in a selected group of spinal cord injury patients with neuropathic bladder dysfunction. Spinal Cord 1998; 36: 409–414.

Stensman R . Adjustment to traumatic spinal cord injury. A longitudinal study of self-reported quality of life. Paraplegia 1994; 32: 416–422.

Manns P, Chad K . Determining the relation between quality of life, handicap, fitness, and physical activity for persons with spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1999; 80: 1566–1571.

Westgren N, Levi R . Quality of life and traumatic spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1998; 79: 1433–1439.

Kennedy P, Rogers B . Reported quality of life of people with spinal cord injury: a longitudinal analysis of the first 6 months post-discharge. Spinal Cord 2000; 38: 498–503.

Acknowledgements

We thank Daniel Loria, Valeria Chiapatti, Maria Luisa Macchia (Spinal Injuries Unit of Torino), Marsilio Saccavini, Luigi Lovati, Agostino Zampa (Rehabilitation Centre of Udine), Mauro Zampolini and Silvano Baratta (Rehabilitation Centre of Trevi), Vladimiro Kosic (Paraplegic Association Friuli Venezia Giulia) for identifying the patients to be interviewed, and P Collodi and S Traietti (Social Cooperative ‘M Iacontino’ Centre for autonomy – Paraplegic Association Roma and Lazio) for the interviews.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Franceschini, M., Di Clemente, B., Rampello, A. et al. Longitudinal outcome 6 years after spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 41, 280–285 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.sc.3101457

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.sc.3101457

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Characteristics of persons with spinal cord injury who drive in Malaysia and its barriers: a cross sectional study

Spinal Cord (2018)

-

A comparison of perceptions of quality of life among adults with spinal cord injury in the United States versus the United Kingdom

Quality of Life Research (2017)

-

Several time indicators and Barthel index relationships at different spinal cord injury levels

Spinal Cord (2015)

-

The association of assistive mobility devices and social participation in people with spinal cord injuries

Spinal Cord (2014)

-

Impact of quality improvement strategies on the quality of life and well-being of individuals with spinal cord injury: a systematic review protocol

Systematic Reviews (2013)