Key Points

-

This paper gives an insight into evidence based dentistry.

-

Determines the use and knowledge of evidence based dentistry by general dental practices.

-

It appears to be the right time for an educational programme targeted at GDPs.

Abstract

Aims To assess general dental practitioners' understanding of, and attitudes towards, evidence based practice (EBP).

Subjects A random sample of general dental practitioners currently practising in the North West of England.

Method A cross-sectional survey using self administered, structured, postal questionnaires in January 2001.

Results A majority of the respondents had some understanding of technical terms associated with EBP. Only 29% (60/204) could correctly define the term EBP. When faced with clinical uncertainties 60% (122/204) of general dental practitioners turned to friends and colleagues for help and advice. Eighty one percent of respondents were interested in finding out further information about EBP (165/204). Barriers to its use included a lack of available time and financial constraints.

Conclusions EBP is not a concept that every dentist is familiar with, however, the general dental practitioners surveyed were enthusiastic and expressed a desire to find out more information on EBD. It appears to be the right time for an educational program targeted at GDPs to enhance their knowledge and use of EBD in everyday practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Evidence based practice (EBP) has been defined as 'the conscientious, explicit and judicious use of current best evidence in making decisions about the care of individual patients'1 and can be seen as a five stage process:

The practice of dentistry is becoming more complex and challenging. Changing photomicrographic patterns, knowledgeable healthcare consumers, rapid technical advances and the information 'explosion' all place greater demands on clinical decision making. The need for reliable information and the electronic revolution have come together to allow the 'paradigm shift' towards evidence based healthcare to progress swiftly. Evidence based dentistry (EBD) closes the gap between clinical research and real world dental practice and provides dentists with powerful tools to interpret and apply research findings.

EBD requires the integration of the best evidence with clinical expertise and patient preferences and therefore it informs, but never replaces, clinical judgement.2 Evidence based health care recognises the complex environment in which clinical decisions are made and the importance of individual patient circumstances, beliefs, attitudes and values.3 The context for change, and what has made the practice of EBD possible, is the electronic revolution, where dentists and patients can now readily access research evidence. As the quality of research reports and therefore the accuracy of the conclusions drawn, vary tremendously, tools are required to help dentists in interpretation and application of the evidence.

As healthcare practitioners, it is important to offer the best possible care for patients. However, few decisions made in the health services are made as a result of good evidence. One aim of EBD is to encourage the ordinary dental practitioner in primary dental care to look for and make sense of the evidence available in order to apply it to everyday clinical problems. It has been shown that evidence based methods can be learned by clinicians of varying backgrounds, at any stage in their careers.4

A key tool in the evidence based approach is the systematic literature review, which differs significantly from the narrative review. Narrative reviews are usually broad in scope, written by experts and are often informal and subjective, supporting the author's views. They are subject to bias and overall conclusions may not be accurate.

Systematic reviews use explicit standards for evidence retrieval, assessment and synthesis. They are undertaken with the same rigour as one expects from the primary research, with each study in the review treated as a unit of analysis, using specific eligibility criteria for its inclusion.5 The methodology of the review is thoroughly documented and reproducible.

The Cochrane Collaboration is an international organisation whose overall aim is to build and maintain a database of up-to-date systematic reviews of randomised controlled trials of healthcare interventions and to make these readily accessible electronically. It has been called an enterprise that rivals the Human Genome Project in its potential implications for modern medicine 6 and has also been described as being one of the most significant clinical advances since the creation of the National Institutes of Health in America.7 The core work of the collaboration is done by the collaborative review groups, which are formed by individuals who have a common interest in a healthcare problem and who work together through electronic means to prepare a systematic review on their chosen topic.8 The Cochrane Oral Health Group is based at the University of Manchester, and has a growing and enthusiastic international membership.

In the medical field, there are many medically related articles both in favour and against EBP. Recent papers have highlighted the need for EBP.9,10 A study in Canada revealed the likelihood that physicians would incorporate evidence based medicine (EBM) into their practice can not be predicted by any demographic or practice related factors, and even those who are enthusiastic about EBM rely more on traditional information sources than EBM-related sources.11 A recent survey of physicians showed that concerns about EBM have been expressed as 'it is time consuming' and that 'EBM ignores clinical experience'.12

In dentistry, however, EBP is still an emerging concept. There is an increasing amount of articles being published which are intended to help clinicians work through the confusion associated with recognising and understanding important clinical research and to give the individual clinician a means to achieve an increased level of confidence in clinical decision making.

A recent series of articles offered the dental practitioner different paradigms for clinical decision making.13 These articles were designed to help the reader determine whether information presented in the dental literature is valid and/or technically correct and also whether it is applicable and usable for a specific treatment in question. A paper by Richards titled 'Is it worth reading this paper',14 helps the reader assess whether a paper is valid and worth reading by using a systematic process of critical appraisal.

A previous study also by Richards outlined several advantages of EBD. A big advantage is that it enables the practitioner to monitor and develop clinical performance.15 Other advantages include improved effective use of research evidence in clinical practice and also the more effective use of resources.

An editorial in the Journal of Dental Research emphasises two parts to EBD, one is research-related and the other is practice-related. 'The practice of EBD requires the blending of research knowledge with provider experience'.16 In the McMaster series on 'How to read the literature',17 two criteria used in determining useful from useless are: 'were the patients similar to your own' and 'is the therapeutic manoeuvre possible in your practice?'.These points always need to be considered for each clinical trial.

However, there is no insight from these articles into how EBP is being accepted within dentistry. The objectives of this study are therefore to assess the current knowledge and use of EBP by general dental practitioners (GDPs), their attitudes towards it and perceived barriers to its use.

Methods

A questionnaire was developed to determine the knowledge, use and attitudes of GDPs towards EBP. In addition to demographic data, the questionnaire consisted mainly of closed questions to assess knowledge and attitudes of GDPs towards EBP. A five point ordinal scale was used to determine opinions on the importance of EBP. Finally, practitioners were given a free text section to make any comments on perceived barriers in the use of EBP.

A pilot study was performed on eight members of staff from the University of Manchester Dental Hospital to determine the acceptability and clarity of the questionnaire and to confirm its face validity. A few minor changes were made before these questionnaires were sent out.

In January 2001, numbered questionnaires were sent to 300 GDPs in the North West region of England. A list of GDPs working in the North West was obtained and the names and addresses placed in a container. Names were drawn at random. The covering letter gave an explanation of the study and a return date was given.

Reminders were sent to non respondents. The data was entered into a spreadsheet and analysed using the statistical package SPSS for Windows 9.0. A coding system was used when the data was entered. The free text section was analysed visually, by looking for common themes.

Results

Of the 300 questionnaires sent out, seven were returned because the practitioners had either moved without a forwarding address or had retired from practice. A total of 204 replies were received to the remaining 293 questionnaires (69.6%).

The majority of respondents (155/204, 76%) were male. Fifty two percent of practitioners (106/204) mainly worked with patients on the National Health Service, approximately 6%(13/204) with private patients, and the remaining with a mixed patient base. Most respondents had been working in practice for more than 15 years (126/204, 62%) (Fig. 1).

In total, there were 14 UK dental schools from which dentist shad qualified and three from abroad. A third had qualified from Manchester, followed by Liverpool (34/204, 17%) and Newcastle (18/204, 9%) (Fig. 2).

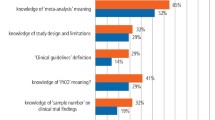

The respondents were asked to score their perceived knowledge of the following terms; EBP, clinical governance, clinical effectiveness, systematic reviews, critical appraisal and Cochrane Collaboration. A majority of the respondents had some understanding of most of the technical terms used in evidence based dentistry. For four of the six terms provided, approximately a quarter of respondents felt they could define each term. Only 18% (37/204) felt able to define the term 'systematic review'. Over 72% of respondents were unaware of the Cochrane Collaboration (148/204) (Fig. 3).

Interestingly, when in the following question respondents were asked to define some of these technical terms, approximately 29%(60/204) defined EBP correctly, 49% (139/204) systematic review, and 68% (139/204) critical appraisal. Differences in those who felt they could define these technical terms, and those who actually correctly defined these terms, were tested using the MannWhitney test. To simplify the presentation of results, the data was transformed to dichotomous variables. There were no significant differences (p = 0.210) in those who felt they could define EBP and those who correctly defined the term. However, there were significant differences in those who felt they could define the terms systematic review (p = 0.019) and critical appraisal (p < 0.001).

The three most important factors in a randomised controlled trial were thought to be the sample size (154), followed by a true randomised sample (100) and thirdly, blinding (94). Intention to treat analysis was seen as being the least important factor (Fig 4).

When faced with clinical uncertainties, 122/204 of the GDPs (60%) turned to friends and colleagues for help and advice, 25/204(12%) consulted a textbook, and only 4/204 (2%) consulted an electronic database. In assessing the importance of evidence-based dentistry in general practice a scale of 1-5 was used, one being very important and five not important. The mode was two (41%),and only one individual rated it as five.

Eighty one percent of practitioners (165/204) were interested in finding out more information on EBP. Many dentists (87%), claim to change practice as a result of reading a research article, mainly due to hugely significant results. A considerable proportion of respondents (86%) have never been on an EBP course.

In the free text section at the end of the questionnaire, respondents were asked to list any perceived barriers to EBP. The main perceived barriers to EBP were a lack of time and financial constraints. Other common barriers were the availability of resources, such as the internet, and the attitudes of patients to change.

A cross tabulation was performed to see if there was a relationship between the place of study and those who can define the term EBP. Those who attended King's or Guy's dental schools had the highest percentage of correct answers (75% and 63% respectively). However, these dental schools only had eight GDPs taking part in the study.

Discussion

The response rate of 69.6% was encouraging, given that response rates to questionnaire surveys among general practitioners have been shown to be dropping.18 The high proportion of male subjects probably reflects the sample, as a majority of the respondents had been practising for more than 15 years. The Department of Health website states that in 1990, 25% of all general medical practitioners and 26% of all medical staff were female.19 In comparison, the male to female dentist ratio is likely to have been of a similar proportion.

As expected, most GDPs had qualified from Manchester and Liverpool, the two nearby dental hospitals.

Respondents had some understanding of the technical terms used in EBP. However, a large proportion were unaware of the Cochrane Collaboration. This is a fast growing international organisation founded in 1992, and is an excellent source of systematic reviews for all areas of healthcare. This unawareness could hinder the use of EBD in general dental practice. Evidence based dentistry is practice that integrates evidence, clinical experience and patient preference. A number of individuals thought that EBD did not incorporate clinical experience. Interpretation of evidence is a fundamental element, and if clinicians feel that their clinical experience is being ignored or under valued, then this may raise negative attitudes towards evidence based dentistry.

Systematic reviews are those that use explicit methods to identify, select and appraise relevant research. A critical appraisal is the process of assessing and interpreting evidence by systematically considering validity, results and relevance. Results showed that many respondents were aware and were able to define these terms. Central to the practice of EBD is the learning of skills needed to appraise articles critically.20

The three most important factors in a randomised controlled trial as thought by respondents were sample size, randomisation of the sample, and blinding. Empirical research examining the impact of different methodological criteria on study findings, has demonstrated that the key domains should always include concealment of treatment allocation, blinding of outcome assessment, and handling of withdrawals and dropouts.21 It is encouraging to find that two out of the three domains were identified by the respondents.

Many GDPs appear to turn to friends and colleagues for help and advice. Although experts may have a wealth of scientific knowledge, clinical experience and credibility, guidelines based on expert opinion are sometimes open to criticisms of bias and conflict of interest. However, experts and colleagues are a quick, cheap and easy to use, source of information and also provide guidance, support, affirmation, and other psychological benefits that computerised sources can not provide.22 The problem with textbooks as a source of evidence is that the information may be more than a decade out of date at the time of publishing.23 Ideally, clinicians should be turning to electronic databases of secondary research eg Cochrane Collaboration and DARE (Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effectiveness). However, these may not be as accessible as colleagues, and do not cover all topics, so it is reasonable to expect these not to be greatly used, but 2% is disappointingly low.

Most respondents felt that the use of EBP is important, and showed great interest in finding out further information. Current lack of knowledge may be hampered by a lack of time, a factor also identified by the respondents as being a barrier to EBP. The dissemination of EBD may not be appropriate, focusing on those in academic settings and excluding those in practice.

Many GDPs claim to have changed practice as a result of reading a research article. Sadly this is often for the wrong reasons. The most common reason given is highly significant results, but the quality of the paper is even more important, and critical appraisal skills should be acquired by practitioners. Many respondents had changed practice just by looking at the authors or the journal the article had been published in. Publication of research findings have been shown to be linked with significant results and are not associated with sample size, presence of a comparison group, or the type of study.24

As many of the respondents worked primarily under the National Health Service, time and funding were major influences on how clinical decisions are undertaken, rather than negative attitudes towards the concept. The practice of EBD is thought by some to be too time consuming. As with any new skill, there is a learning curve to overcome and with experience, clinical problems will quickly become focused questions and the best evidence can then be tracked down efficiently. There are a number of ways of increasing the time available for practising EBD. Davidoff and colleagues suggested that a general physician would need to read 17 articles each day to keep up with the current medical literature. 25 Family physicians have expressed great interest in having patient education materials, drug information, and overviews of treatment recommends available on computers.26 The same could be applied to dentistry. In the National Health Service, the Dental Practice Board could help by sending back prior approvals with the latest evidence.

More emphasis should be made towards training, accessing and interpreting evidence, and then spending time putting these skills into practice. Sackett et al. have suggested that a journal club can be a useful forum to develop and enhance critical appraisal skills.27 The peer review scheme has been in operation since the early 1990s and, after five years, over one third of the GDP population in England had taken part.28 In peer review, groups of dentists meet together, share experiences and identify changes that could lead to improvements in their service to patients.

Lack of resources, as pointed out by respondents, was another important barrier. Gaps exist in the extent to which technology has been fully integrated into dental practices. This is partially the result of continuously emerging techniques and partially attributable to different attitudes among dentists towards innovation. Further development of EBD is needed before it becomes a productive and widely used part of practice.29

Conclusions

EBP may not be a concept that every dentist is familiar with, but increasing consumer pressures and the present economic, social, and political changes, will necessarily demand that evidence based principles are implemented.

GDPs surveyed were enthusiastic and expressed a desire to find out more information on EBD. It appears to be the right time for an educational program targeted at GDPs to enhance their knowledge and use of EBD in everyday practice, using a systematic approach with strategic planning. The implementation of these findings is vital for optimising patient outcomes, improving clinical practice, providing cost effective high quality care and enhancing the credibility of dentists. The ability to evaluate the literature and incorporate the findings into clinical practice is an important aspect of dental education. This may be one of the most important skills that we can pass to the next generation of GDPs.

References

Sackett DL, Richardson S, Rosenberg W, Haynes RB Evidence-based medicine: how to teach and practice EBM. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingston 1999.

Sackett D, Richardson W, Rosenberg W, Haynes R Evidence-based medicine: how to practice and teach EBM. London: Churchill Livingstone 1997.

Browman GP . Evidence-based paradigms and opinions in clinical management and cancer research. Sem Oncol 1999; 26 (Suppl 8): 9–13.

Rosenberg W, Donald A . Evidence-based medicine: an approach to clinical problem solving. Br Med J 1995; 310: 1122–1126.

Browman G . Evidence-based cancer care and clinical practice guidelines. Am Soc Clin Oncol 1998 (Spring Educational Book) 451–457.

Naylor D . Grey zones of clinical practice: some limits of Evidence-based medicine. Lancet 1995; 345: 840–842.

Dickersin K, Manheimer E . The Cochrane Collaboration: evaluation of health care and services using systematic reviews of the results of randomised controlled trials. Clin Obstet Gynecol 1998; 41: 315–331.

Jadad AR, Haynes RB . The Cochrane Collaboration - advances and challenges in improving Evidence-based decision making. Med Decis Making 1998; 18: 2–9.

Risdale L . Evidence-based learning for general and family practice. Br J Gen Pract 1996; 46: 503–504.

Dawes M . On the need for Evidence-based general and family practice. Evidence-based Med 1996; 1: 68–69.

McAlister FA, Graham I, Karr GW, Laupacis A . Evidence-based medicine and the practising clinician. J Gen Intern Med 1999 Apr; 14: 236–242.

Olatunbosun OA, Edouard L, Pierson RA . Physicians' attitudes toward Evidence-based obstetric practice: a questionnaire survey. Br Med J 1998; 316: 365–366.

McGivney GP . Evidence-based dentistry series. J Pros Dent 2000 Jan; 83: 11.

Richards D . Is it worth reading this paper. Evidence-based Dent 2000; 2: 50–52.

Richards D, Lawrence A . Evidence-based dentistry. Br Dent J 1995; 179: 270–273.

Bader E, Ismail A, Clarkson J . Evidence-based Dentistry and the dental research community. J Dent Res 1999; 78: 1480–1483.

Department of Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics, McMaster University, Hamilton Ontario How to read clinical journals: I. Why to read them and how to start reading them critically. Can Med J 1981; 124: 555–558.

McAvoy BR, Kaner EFS . General practice surveys: a questionnaire too far. Br Med J 1996; 313: 732–733.

Department of Health. Hospital, public health medicine and community health service medical and dental workforce statistics for England.

Sackett DL, Rosenberg WMC . On the need for Evidence-based medicine. J Roy Soc Med 1995; 88: 620–624.

Juni P, Witschi A . The hazards of scoring the quality of clinical trials for meta-analysis. J Am Med Assoc 1999; 282: 1054–1060.

Slawson DC, Shaughnessy AF . Obtaining useful information from expert based sources. Br Med J 1997; 314: 947–949.

Weatherall DJ, Ledingham JGG, Warrell DA . On dinosaurs and medical textbooks. Lancet 1995; 346: 4–5.

Dickersin K, Min YI, Meinert CL . Factors influencing publication of research results. J Am Med Assoc 1992; 267: 374–378.

Davidoff F, Haynes B, Sackett D, Smith R . Evidence-based medicine. Br Med J 1995; 310: 1085–1086.

Ebell MH, Gasper DL, Khurana S . Family physicians' preferences for computerised decision support hardware and software. J Fam Pract 1997; 45: 137–141.

Sackett DL, Haynes RB, Guyatt GH, Tugwell P Clinical epidemiology: a basic science for clinical medicine. 2nd ed Boston 1991 pp 398–418.

Department of Health. Peer Review and Clinical Audit in General Dental Practice. London: Department of Health 1997.

Manski RJ . Translating clinical practice into Evidence-based research through the use of technology. J Am Coll Dent 2000; 67: 30–32.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr T. Macfarlane, who provided statistical advice and the NorthWest GDPs who took part in the survey.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Iqbal, A., Glenny, AM. General dental practitioners' knowledge of and attitudes towards evidence based practice. Br Dent J 193, 587–591 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4801634

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4801634

This article is cited by

-

New dental graduates transition into UK professional practice; a longitudinal study of changes in perceptions and behaviours through the lens of evidence-based dentistry

BMC Medical Education (2024)

-

A longitudinal study of changes in new dental graduates' engagement with evidence-based practice during their transition to professional practice

British Dental Journal (2022)

-

Dentists' awareness and knowledge of evidence- based dentistry principles, methods and practices: a systematic review

Evidence-Based Dentistry (2022)

-

A national cross-sectional survey of the attitudes, skills and use of evidence-based practice amongst Spanish osteopaths

BMC Health Services Research (2021)

-

How evidence-based is dentistry anyway? From evidence-based dentistry to evidence-based practice

British Dental Journal (2020)