Key Points

-

GDPs are the principle dental care providers for patients with complex medical conditions.

-

There are patient groups viewed as at risk from procedural bacteraemia that are not specifically covered by any standard clinical guideline and physicians may view them as being excepted from standard guidance on antimicrobial prophylaxis.

-

Physicians' opinions and prescribing practice are often determined locally and require consideration.

Abstract

Background Concern that some catheter related bloodstream infections (CRBSI) arise from dental treatment in home parenteral nutrition (HPN) patients results in recommendation of antibiotic prophylaxis. Clinical guideline 64 is widely recognised and observed. There is a lack of consistent guidance for other patient groups viewed at risk from procedural bacteraemia.

Methods 1. An email survey of the British Association for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (BAPEN) HPN group, requesting physicians' opinions, observations and practises relating to oral health and CRBSI prevention; 2. Comparison of oral health parameters and dental treatment in relation to patient reported 12 month CVC infection history, using chi-square analysis to assess associations in 52 HPN patients.

Results 1. Sixty-eight percent of the UK HPN Group responded. Fifty percent linked oral health/dental treatment with the possibility of CRBSI, 39% were unsure. Sixty-one percent had recommended parenteral prophylactic antibiotics (82% IV, 18% IM), mainly following the historic infective endocarditis (IE) dental prophylaxis guidelines. Infection with streptococci, prevotella and fusobacteria caused most concern. Amoxicillin, metronidazole, co-amoxyclav and gentamycin were the most prescribed antibiotics. Thirty-six percent might delay HPN if oral health was poor; 57% had recommended dental examination and 25% dental extractions, to prevent or treat CRBSI. 2. Associations between patient recalled CVC infection and their current dental status, the interval since dental treatment or the prophylaxis received over the previous 12 months did not achieve significance.

Conclusions Opinion varies among UK HPN providers on the role of dental treatment and oral health in CRBSI and on prescribing prophylactic antibiotics for dental treatment. Prophylaxis guidance specific to this patient group is required.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Patients with intestinal failure (IF) are dependent on parenteral (intravenous) nutrition (PN) to meet their everyday fluid, energy and nutritional needs. Medical and nutritional management, long term PN (HPN) and in particular, prevention of associated complications have been cited as contributing to the poor oral health of this group, partly by complicating access to oral healthcare.1

Parenteral nutrition infusion is patient specific and delivered by tunnelled central venous catheter (CVC). The catheter tip is positioned at the junction of the superior vena cava and right atrium.2

Antibiotic prophylaxis for dental procedures in people with intravascular access devices such as arterio-venous anastomoses in dialysis patients and central venous catheters in patients with intestinal failure remains an area where practice and policy are often determined locally. Oral bacteraemia is recognised as an everyday event and the linking of dental treatment to subsequent distant site infection has been limited in part by the inability to achieve sample sizes large enough for results to be meaningful.3,4

Central venous catheter related bloodstream infection (CRBSI) is associated with both significant morbidity and mortality in IF patients.5 Coagulation negative Staphylococcus, Staphylococcus aureus, Staphylococcus epidermidus, gram negative bacilli, Candida and Klebsiella are the most common pathogens6 and infection rates generally can be related to the quality of aseptic technique used.7,8

Repeated access site infections, CRBSI and all candidal CRBSI, require catheter removal and result in the sequential loss of limited venous access routes.5 Endocarditis,9 renal failure10 and osteomyelitis11 have been attributed to CRBSI in this patient group. Dental treatment and oral infection have been reported as causal factors.12,13

Concern among physicians to mitigate the risk of CRBSI from dental procedural bacteraemia results in the recommendation of antibiotic prophylaxis.14 Prophylaxis recommendations for dental treatment in central venous catheter populations15,16,17 are at odds with the British Society for Antimicrobial Chemotherapy view that there is a lack of evidence supporting routine prophylaxis to prevent CRBSI.

For patients, fear of therapy related complications accompanies the negative impact of HPN on physical, psychological and social domains.18

The Oley Foundation provides the HPN community worldwide with information and support. It lists dental abscess, caries and routine dental treatment as sources of systemic infection, and recommends antibiotic prophylaxis after liaison with the physician.19 HPN patients and their carers have needed to insist upon its use.20

Oral health risk factors in this patient population have been highlighted as contributing to dental disease and infection risk, and their oral health has been found to be poorer than the UK norm.1 People with complex medical conditions and disability have been found to have poorer oral health and oral healthcare outcomes.20,21,22

Familiarity with a medical condition has been shown to influence the dental practitioner's confidence to treat the patient.23 This group's more complex management needs may impact on dentists' attitudes and thus on people's ability to access dental services.24 After withdrawal of antimicrobial prophylaxis recommendations to prevent infective endocarditis3 it is likely that confusion and conflict of opinion arising between physicians, patients and the dental profession could affect access to oral health for the HPN patient group.

Method

The aim of this study was to establish the prescribing practice of and the beliefs and experience informing antibiotic prophylaxis for dental treatment among UK HPN centres and to evaluate oral health status and dental experience in relation to patient recalled CVC infection.

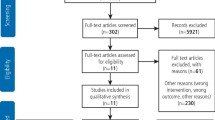

A national survey of HPN centres' dental prophylaxis prescribing practice was carried out alongside an analysis of patient reported 12 month CVC infection history in the light of their IF status, oral health, dental care history, and antibiotic prophylaxis for dental procedures.

The study groups amassed the total population of consultant physicians who were members of the British Association for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (BAPEN) HPN group or BAPEN Medical, and a voluntary, self-selecting, convenience sample of consenting patients attending the Intestinal Failure Unit at St Mark's Hospital, Harrow. Permission to canvas BAPEN members was granted after the protocol was presented at the HPN Group Study Day, May 2008.

Management permission from the research and development department of north west London hospitals followed approval from Harrow Research Ethics Committee in June 2008.

Where possible, questions relating to oral health behaviours, attitudes, and barriers to seeking and receiving care were drawn from the adult dental health survey25 so that the study group responses could be compared with those of the general population. Caries experience was recorded using its diagnostic criteria.

No dental tissue manipulation was undertaken to avoid procedural bacteraemia. Oral hygiene was scored according to visual observation of supragingival plaque and calculus. Those people with normative need were informed.

Pearson's chi-square test was used to test the null hypothesis that oral health and dental experience occurring in the HPN cohort CVC infection patients were random and not linked to CVC infection history. Differences were regarded as statistically significant when the p value was <0.05

The cohort sample numbered 52: 17 male and 35 female, with a mean age of 51.9 years (SD 14.6, range 19-77 years). HPN use ranged from 6 months to 18 years with a mean of 4 years 10 months (SD 4.4 yrs). This represented 28% of the unit's HPN population. All participants recounted their medical history and underwent structured interview and oral health examination.

The background conditions causing intestinal failure (IF) were grouped according to the British artificial nutrition survey (BANS) diagnostic categories26 to facilitate comparison with the national statistics. Figure 1 provides the details.

Results

Prescribing practitioners' questionnaire

The questionnaire was sent to 41 consultant physicians managing HPN patients. Twenty-eight valid responses were received; a response rate of 68%, of whom 86% had been in post for at least 5 years.

Fifty percent (14) believed that oral/dental health may be a cause of CRBSI and 39% (11) were uncertain. Five case histories were specifically recalled where CRBSI was attributed to oral sepsis and/or dental treatment.

Prophylactic antibiotics before dental treatment were routinely prescribed by 43% (12). Sixty-one percent (17) would cover oral surgical procedures or an extraction, 46% (13) cover fillings, and 25% (7) periodontal therapy.

Of all respondents, 32% (9) detailed their prophylaxis regime. Amoxicillin, metronidazole, co-amoxyclav and gentamycin were the most cited antibiotics. Intravenous (82%) or intramuscular (18%) administration was preferred. Oral pathogens of most concern were streptococci, prevotella and fusobacteria.

For 46% (13) a patient's poor oral health would never delay the commencement of parenteral nutrition, 36% (10) said it may on occasion. A newly placed CVC was not viewed as requiring the deferral of dental treatment (89% (25)).The majority (68% (19)) had never recommended oral health screening before CVC placement.

Table 1 details the dental procedures physicians had recommended to prevent or manage CRBSI. Opinion was divided on where these patients should receive their dental care, however, 72% were anticipating routine access to specialist centres (Fig. 2).

HPN patients

Just over three quarters of patients (77% (40)) had been advised to have antibiotic cover for some types of dental treatment, of whom 68% (27) had always followed this advice. Following the introduction of Clinical Guideline 643 two patients had no longer been able to access it. Six people had never followed the prophylaxis recommendation (in one case because the GDP had refused), and 18% (7) had not yet accessed dental treatment.

Of the 40, 35 recalled the regimen that had been recommended. Twenty percent (7) clearly recalled oral antibiotics as their recommended means of prophylaxis (despite the risk of malabsorption); 80% recalled the need for intramuscular and/or IV antibiotics, and 50% (14) of the latter group reported increased difficulty in accessing care. For six individuals, access to both dental treatment and antibiotic prophylaxis required referral to either hospital or community dental services.

Difficulties were described relating to timing dental appointments to coincide with availability of their GP/practice nurse (often resulting in treatment deferral) and getting the GDP/GP to understand the need for antibiotics. Advice to patients from HPN teams regarding which dental procedures would require cover was found to be variable and had led to confusion.

Twenty-eight patients recalled one or more CVC infections in the past 12 months. After combining the incidence of CVC infection with the results of the oral health survey, analysis of oral health treatment experience and prophylaxis correlation with patient recalled CVC infection was possible.

The effect of each variable on infection recalled and no infection recalled populations were tested. Presence of calculus, the interval since last dental treatment, the prophylaxis advice received, and whether or not it was followed did not correlate significantly with patients' recalled CVC infection experience in the previous 12 months. Additionally, neither patients' IF diagnosis nor the presence of a stoma, a recognised risk factor for CVC infection, significantly related to infection experience. Table 2 provides the p values found using Pearson's chi square test for all these parameters.

HPN patients were found to attend the dentist more regularly than other adults in the ADHS South region, 71% and 60% respectively. The time since people's last dental appointment is set out in Figure 3. For 77% (40) it had been a planned procedure, while for 23% (12) it had been an emergency visit. In 89% (46) of cases, people attended their regular practitioner. Additionally, 17% (9) reported receiving dental treatment in a hospital setting at some point during their illness.

Having a back tooth saved was preferable for 58% (30) compared to 80% nationally, a front tooth would be saved by 82% (43), compared to 92%. As in the ADHS 69% (36) found the prospect of losing all their teeth and having complete dentures upsetting.

Sixty percent of the patient population reported current problems with their teeth and/or mouth. Almost one third of the group (31% (16)) had a denture of some type. The majority (75% (12)) felt they were unsatisfactory.

Reported denture wear and hygiene practices resulted in the majority being at increased risk of oral Candida colonisation. The oral examination found that 14% (7) of the study group presented with oral or perioral signs commonly associated with oral candidal infection.

Discussion

HPN patients recognise that management of HPN associated complications is of paramount importance to their prognosis.27,28,29 Those prone to management complications were represented in greater number than in the national HPN patient group due to recruitment from a tertiary referral centre.30 However, in general, the cohort paralleled and reflected the national profile.

Concern that oral health and CRBSI may be linked, in addition to personal difficulties accessing dental care may have led to those with CVC infection history or poor oral health volunteering in greater number. When testing perceived oral health and dental treatment risk factors for CVC infection, this study illustrated trends rather than statistically significant differences. People demonstrating poorer compliance with recognised oral health practises were generally the group reporting CVC infections, however, this did not achieve significance. A larger sample may have powered the comparison sufficiently to allow the correlation to be significant.

The results of the prescribing practitioners' survey reflect the opinion of experienced specialist physicians, who influence the care pathway of HPN patients and within this, the value to be placed on oral health and antibiotic prophylaxis in controlling CRBSI risk.

Knowledge of dental procedures perceived to cause bacteraemia by physicians did not match those previously identified as requiring prophylaxis in British Society for Antimicrobial Chemotherapy31 or the American Heart Association's Endocarditis prevention guidance.32 There was a general expectation that their patients would have access to specialist or secondary care to facilitate dental treatment. In fact, care is in the main being delivered by their general dental practitioners.

Forty percent reported difficulties with access. Limited local availability of NHS dentists, physical access difficulties because of disability, their complex medical history and particularly the requirement for prophylaxis, contributed to care being delayed or withheld. Lack of clarity on procedures to be covered alongside the need for intramuscular or intravascular antibiotic administration resulted in confusion, debate and led to delays and frustration. However, requests for oral antibiotic prophylaxis generally allowed seamless care to be delivered.

Patients reported deferring dental care because of other health priorities and concern that treatment might cause a CVC infection. This belief informed some treatment choice decisions and contributed to election for extraction. This trend may not serve the HPN patient's long-term oral, nutrition-related, psychological or social health. Denture wear alongside the xerostomia reported in this group1 will generate further risk factors to oral health,20,33,34 potentiating risk of oral candidiasis, reported as a significant concern for CRBSI.12

Conclusion

Central venous catheter infection was not uncommon in this cohort. CRBSI prophylaxis and in particular the need for its intravenous or intramuscular administration had complicated access to dental care for over one third of patients. Although trends emerged, no statistically significant relationship between any of the oral health parameters tested and patient recalled CVC infection experience was shown. The importance of good oral health should form part of the information given to people while they are acquiring HPN aseptic technique skills.

Physicians managing intestinal failure with parenteral nutrition believe that oral health and dental treatment may be implicated in catheter related bloodstream infections. Prophylactic antibiotics were routinely recommended by 43% but there is currently no consensus or clear guidance on prescribing for this patient group.

Further study is recommended to establish whether there is a link between dental treatment/infection and CRBSI and to inform a clear guideline on appropriate use of antibiotic prophylaxis for this group.

References

Lee A M . The oral health of people receiving home parenteral nutrition. London: University of London, 2009. MSc thesis.

NICE. Nutrition support in adults: oral nutrition support, enteral tube feeding and parenteral nutrition. Clinical guideline 32. London: National Institute for Health and of Clinical Excellence, 2006. Online article available at http://www.nice.org.uk/CG32 (accessed September 2010).

NICE. Antimicrobial prophylaxis against infective endocarditis. Clinical guideline 64. London: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, 2008. Online article available at http://www.nice.org.uk/CG64 (accessed December 2011).

Roberts G J . Dentists are innocent! 'Everyday' bacteraemia is the real culprit: a review and assessment of the evidence that dental surgical procedures are a principle cause of bacterial endocarditis in children. Paediatr Cardiol 1999; 20: 317–325.

Ireton-Jones C, DeLegge M . Home parenteral nutrition registry: a five-year retrospective evaluation of outcomes of patients receiving home parenteral nutrition support. Nutrition 2005; 21: 156–160.

Rannem T, Ladefoged K, Hegnhøj J, Møller E H, Bruun B, Jarnum S . Catheter related sepsis in long term parenteral nutrition with Broviac catheters. An evaluation of different disinfectants. Clin Nutr 1990; 9: 131–136.

Messing B . Catheter-related sepsis during home parenteral nutrition. Clin Nutr 1995; 14(Suppl 1): 46–51.

Johnston D A, Richards J, Pennington C R . Auditing the effect of experience and change on home parenteral nutrition related complications. Clin Nutr 1994; 13: 341–344.

George R L, Cornel G . Subendocardial abscess as a complication of prolonged central venous assess for parenteral nutrition. Can J Surg 1992; 35: 91–93.

Yared G, Seidner D L, Steiger E, Hall P M, Nally J V . Tunnelled right atrial catheter infection presenting as renal failure. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 1999; 23: 363–365.

Corso F A, Shaul D B, Wolfe B M . Spinal osteomyelitis after TPN catheter-induced septicemia. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 1995; 19: 291–295.

Nightingale J M, Simpson A J, Towler H M, Lennard-Jones J E. Fungal feeding-line infections beware: the eyes and the teeth. J R Soc Med 1995; 88: 258–263.

Culkin A, Gabe S M, Bjarnason I, Grimble G, Madden A M, Forbes A . A double-blind, randomized, controlled crossover trial of glutamine supplementation in home parenteral nutrition. Eur J Clin Nutr 2008; 62: 575–583.

Pennington C R . Parenteral nutrition. In Nightingale J (ed) Intestinal failure. pp 497–511. London: Greenwich Medical Media Limited, 2001.

Spuller R L . The central indwelling venous catheter in the paediatric patient – dental treatment considerations. Spec Care Dentist 1988; 8: 74–76.

French G L . How should prophylactic antibiotics be used during dental work or bacteraemia associated procedures? Paed Nephrol 1993; 7: 346.

Aptekar A, Sandor G K B . Point of Care. What precautions do I need to take when providing dental treatment to a patient with a central venous catheter? JCDA 2006; 72: 619–628.

Chambers A, Hennessey E, Powell-Tuck J. Longitudinal trends in quality of life after starting home parenteral nutrition: a randomised control study of telemedicine Clin Nutr 2006; 25: 505–514.

The Oley Foundation. HPN complication chart. 2009. Online article available at http://www.oley.org/charts/newHPN.pdf (accessed December 2011).

Wylie I . Oral healthcare for older people: 2020 vision. Gerodontology 2003; 20: 60–62.

Machuca G, Nieves E, Sanchez A F, Machuca C, Bullon P . Descriptive study factors modifying the periodontal status of a population of people with a learning disability in Spain. J Disabil Oral Health 2007; 8: 73–80.

Tiller S, Wilson K I, Gallagher J E . Oral health status and dental service use of adults with learning disabilities living in residential institutions and in the community. Community Dent Health 2001; 18: 167–171.

Ellervall E, Brehmer B, Knutsson K . How confident are general dental practitioners in their decision to administer antibiotic prophylaxis? A questionnaire study. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2008; 8: 57.

Kiyak H A . Impact of patients' and dentists' attitudes on older persons' use of dental services. Gerodontics 1988; 4: 331–335.

Kelly M, Steele J, Nuttall N et al. Adult dental health survey: oral health in the UK 1998. London: The Stationery Office, 2000.

British Association for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition. Annual BANS report 2010. Artificial nutrition support in the UK 2000–2009. Redditch: BAPEN, 2010. Online article available at http://www.bapen.org.uk/pdfs/bans_reports/bans_report_10.pdf (accessed December 2010).

Scolapio J S, Fleming C R, Kelly D G, Wick D M, Zinsmeister A R . Survival of home parenteral nutrition patients: 20 years of experience at the Mayo Clinic. Mayo Clin Proc 1999; 74: 217–222.

Lloyd D A J, Vega R, Bassett P, Forbes A, Gabe S M . Survival and dependence on home parenteral nutrition: experience over a 25-year period in a UK referral centre. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2006; 24: 1231–1240.

Jeejeebhoy K N . Treatment of intestinal failure: transplantation or home parenteral nutrition? Gastroenterology 2008; 135: 303–305.

Irving M H . An intestinal failure unit. In Nightingale J (ed) Intestinal failure. pp 469–473. London: Greenwich Medical Media Limited, 2001.

Gould F K, Elliott T S, Foweraker J et al. Guidelines for the prevention of endocarditis: report of the Working Party of the British Society for Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. J Antimicrob Chemother 2006; 57: 1035–1042.

Dajani A S, Taubert K A, Wilson W et al. Prevention of bacterial endocarditis. Recommendations by the American Heart Association. JAMA 1997; 277: 1794–1804.

Arendorf T M, Walker D M . The prevalence and intra-oral distribution of Candida albicans in man. Arch Oral Biol 1980; 25: 1–10.

Wilson J . The aetiology, diagnosis and manage-ment of denture stomatitis. Br Dent J 1998; 185: 380–384.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express appreciation for the help of the UK HPN Group membership, in particular Janet Baxter PhD, Clinical Network Manager, Dr Emma Greig PhD MRCP (BAPEN Medical), the contribution and guidance of Dr Janice Fiske OBE MPhil and statistical support from Ron Wilson, KCL Dental Institute. Alison Lee is grateful for the facilitation of this study by Hillingdon Community Health Dental Referral Service.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, A., Gabe, S., Nightingale, J. et al. Oral health, dental prophylaxis and catheter related bloodstream infections in home parenteral nutrition patients: results of a UK survey and cohort study. Br Dent J 212, E4 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2012.50

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2012.50