Abstract

Objectives:

This paper reviews the literature concerning psychological adjustment to spinal cord injury, focusing on the recent methodological developments and new directions in research.

Method:

Several literature reviews using the search terms Spinal Cord Injury, Paraplegia, Coping and Adjustment were undertaken using the databases in Pubmed, Medline and Embase. The papers that were published from 2001 onwards, written in English and used a sample of adults were included.

Results:

The literature reviewed lends further support to the importance of appraisals and coping strategies in the adjustment to spinal cord injury. Methodological issues highlighted in earlier reviews are addressed in conjunction with further theoretical explorations.

Conclusions:

Although many of the methodological criticisms have been addressed, there remains a need for longitudinal research into the process of adjustment to spinal cord injury and the contributory role of appraisals and coping strategies. Measurement tools designed specifically for use within the spinal cord injured population should be utilized in the prevention of maladaptive adjustment issues, whereas able-bodied comparison groups would allow identification of coping strategies unique to the spinal cord injured population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

A large amount of research data suggest that people tend to adjust well after sustaining a spinal cord injury (SCI), a finding attributed to the high frequency of adaptive coping strategies reported in this population.1 However, variability in adjustment does exist in this population and some individuals remain vulnerable to experiencing psychological difficulties. Elevated levels of anxiety have been reported in 23–35% of the SCI population and elevated levels of depression in 35–38%,2 and people with SCI are found to be more vulnerable to suicide than the general population.3

In addition to the emotional distress experienced, problems with adjustment can affect other areas of functioning. For example, it has been suggested that problems with adjustment are linked to self-neglect,4 which can in turn impact on the physical well-being and increase the likelihood of the onset of secondary complications.5 Difficulties have also been linked to substance abuse,6 which may contribute to further health problems.

Adjustment has also been identified as important for achieving long-term goals; individuals with lower mood levels have been observed to experience more difficulties in gaining employment and engaging in leisure and community activities.1

This is therefore an important area of study to better understand the process of adjustment and identify possible interventions through which it may be facilitated. This paper will examine the studies on coping and adjustment to SCI from 2001 to the present date, reflecting on issues highlighted in earlier review of the literature7 and in new directions of research into factors affecting adjustment.

Method

Several literature reviews using the search terms Spinal Cord Injury, Paraplegia, Coping and Adjustment were undertaken using the databases in Pubmed, Medline and Embase. The papers that were published from 2001 onwards, written in English and used a sample of adults were included in this literature review.

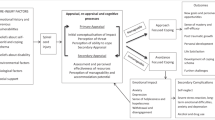

Summary of earlier findings

Galvin and Godfrey7 reviewed the literature on adjustment to SCI with the application of the Stress, Appraisal and Coping model (SAC).5 They reported that a substantial amount of variance in adjustment to SCI can be predicted by psychological factors, with appraisals consistently identified as mediating this process. However, as methodology tended to focus on appraisals assessing attribution of blame to the event of sustaining an SCI, a need for further research into the nature of general appraisals in coping and adjustment was identified.

The authors also noted the dominant presence of coping strategies within the literature, which were found to be consistently strong predictors of adjustment to SCI. Owing to the reliance on cross-sectional studies, it was proposed that there was a need for more longitudinal research to assess the effectiveness of coping strategies across time. The use of intervention strategies were identified as an area, which could be developed through further research, and the authors also endorsed the development of scales designed specifically for the SCI population. Pre-injury factors were highlighted as being of importance when explaining the remaining variance in SCI adjustment and in order to shift the focus away from solely examining coping strategies.

The following sub-sections will identify how researchers within this field have responded to these suggestions.

Addressing empirical issues

Coping strategies across time

Kennedy and Pollard6 responded to the need to assess coping strategies longitudinally using the COPE, Beck Depression Inventory, Anxiety State Inventory, Social Support Questionnaire, Functional Independence Measure and Post-Traumatic Growth Inventory; assessing participants up to 10 years post-discharge. Depression and anxiety levels were found to vary little across the time period, and coping strategies were also found to be relatively stable, highlighting the significance of early symptoms in emotional distress and the importance of early intervention. In addition, the stability of coping measures in the study suggests that there may be a dispositional component to coping, which may also account for some heterogeneity in the SCI population and the possibility of early prediction of adaptation outcome.

The development of specific coping measures

The ‘Spinal Cord Lesion-Coping Strategies Questionnaire’ was developed by Elstrom et al.8 in order to address the need for high-quality coping assessment tools specifically designed for use in the SCI population. On the basis of the qualitative data from interviews of 274 people with SCI, the team developed a scale comprising of three factors: acceptance, fighting spirit and social reliance. Further psychological outcome scales of helplessness, intrusion and personal growth were included in the questionnaire. Multiple regression analysis showed the three coping strategies to account for over half the variance for helplessness and half of the variance in intrusion and personal growth.

The scale was found to exhibit good psychometric properties. Fighting spirit correlated positively with personal growth, and social reliance was found to correlate positively with helplessness and intrusion; emphasizing the negative impact externalized control can have. Furthermore, this scale addressed the problems highlighted by Galvin and Godfrey7 with respect to its sensitivity to situational coping as opposed to dispositional coping.

Pre-injury factors

Other variables contributing to the variance in psychological adjustment were examined by Elfstrom et al.8 After controlling for possible background variables, the effects of coping strategies on psychological adjustment were examined. Sociodemographic variables and disability-related variables were found to be the weak predictors, whereas coping strategies were found to account for a large proportion of variance in adjustment.

By focusing on individuals, who have adjusted well to their injury, it was hypothesized that protective personality traits could be identified. Kinder9 examined the concept of ‘hardiness’ when applied to the SCI population. Kinder9 describes hardiness as taking responsibility to make decisions for one's own life (control), demonstrating commitment to choices one makes (commitment), and constructing possibilities and alternatives to problems (challenge). In those who were identified as showing hardiness qualities, the coping strategies employed focused on change, positive health behaviours and use of activistic social support. A model of control, commitment and challenge in relation to women with paraplegia was constructed by the researchers, control relating to the ability to make decisions based on choices of care, commitment was based on achieving individual goals and sustaining independence and challenge translates to solving problems and achieving mastery. These findings indicated that people with SCI scoring high on measures of hardiness may be more likely to engage in positive coping strategies. However, due to the small, military based sample there are limitations in extrapolating the data to the whole population.

In the study by Hampton,10 127 outpatients completed a postal questionnaire consisting of a general self-efficacy scale, self-related health scales, perceived social support scale and assessments of psychological well-being. Youth and higher income were the only demographics reported to be significantly related to well-being, with other factors, such as positive perception of health, high efficacy and high social support showing significant relationships. Self-efficacy, social support, perceived health and age at time of injury were identified as major predictors of the variance in well-being, accounting for 36% of the variance.

Interventions and treatment

The body of literature available promotes the role of coping strategies in psychological adjustment.1, 2, 5, 6, 7, 8, 11 Such findings have informed clinical practice, and the use of cognitive-based interventions in improving psychological adjustment evaluated. In the study by Kennedy et al.,2 45 patients participated in a CET (coping effectiveness training) programme and compared with patients receiving the standard levels of care on measures of anxiety, depression, coping strategies and self-perception. Results showed lower scores for depression and anxiety for the intervention group compared with the control group.

However, no significant changes were observed for the coping strategies used by participants and the authors proposed that the effectiveness of the programme may be attributed to participants making more positive appraisals about their situation. Further research is required to elucidate the relationship between possible changes in appraisals and psychological well-being. Comparisons of group level or individual-based interventions, and trials with able-bodied participants may allow researchers to identify the mechanisms responsible for changes in mood without observed changes in coping strategies.

Kennedy et al.11 reported an additional study of coping effectiveness training looking at 21 patients who benefited from CET and 23 who did not. These two groups were compared in terms of gender, age, level, completeness of injury and time since injury. Less time since injury seemed to be associated with those who benefited from the programme and no significant difference was observed for the remaining demographics. Surprisingly, coping strategies were not found to predict those who benefited from the programme. Self-perception scores, however, did differ for the scale ‘as I am’: participants who benefited from the CET were found to perceive themselves less confident, more active, more withdrawn and interested before intervention. This suggests that CET may tap into the appraisal process rather than the selection of coping strategies. A limitation of the design of study may have been the use of the Beck Depression Inventory, as this scale includes somatic items that may be linked to SCI rather than depression.

Appraisals

More recent research has shifted from the focus on appraisals of the cause of injury to the appraisal of having an SCI. In the study by Kennedy et al.,1 a postal survey design was used to examine appraisals across four European countries. Overall, participants were found to be well-adjusted psychologically. Participants were found to score low on ‘threat’ appraisals, which assesses potential problems for the future and low on ‘loss’ appraisals, which evaluates the damage from the injury. Overall, the highest reported appraisal was challenge, which is viewed as evaluating the event as a chance for growth and mastery. This may account for the high scores of psychological adjustment observed in the sample.

Kennedy et al.12 found appraisals to account for 12% of the variance in anxiety and 34% of the variance in depression. The scale used in the above studies was the ALEs (appraisal of life events) scale—the only existing measure of appraisals.

Dean and Kennedy13 responded to this issue in the development of the primary and secondary appraisals of disability scale (ADAPSS) Six subscales were identified: ‘growth and resilience’, ‘determined resolve’, ‘personal agency’, ‘fearful despondency’, ‘overwhelming disbelief’ and ‘negative perceptions of disability’. The scale was found to show good validity and reliability and found to account for a large proportion of the variance in depression and anxiety, showing potential to be a valid and reliable clinical measure of appraisals after an SCI.

New directions in factors affecting coping

Social cognition

Buunk et al.14 examined the role of social comparison strategies with respect to coping, assessing the type of comparison a person has a tendency to use when comparing themselves to others with SCI. Analysis of the data from the identification/contrast questionnaire found the role of social comparison strategies to be a mediator between the onset of injury and selection of coping strategies.

Upward contrast (perceiving others as better off) and downward identification (seeing those worse off as potential self-future) were found to be associated with the coping strategies ‘wishful thinking’ and ‘blaming others’. Downward identification was also found to be related to higher levels of depression. These results suggest a link between the style of social comparison used and the type of coping strategy employed. The findings of this study, however, are limited by the small sample size and makes generalization to the whole population tenuous.

Sense of coherence

Lustig15 examined the role of sense of coherence (SOC) in adjustment to SCI. Described as a belief that the world is manageable, meaningful and comprehensible, SOC was investigated in a sample of 48 SCI patients when grouped according to the SOC strength post-injury. Results found that weakened SOC was positively correlated to non-adaptive strategies, such as anger and hostility, and negatively associated with adjustment. Strong SOC scores, conversely, were associated with adaptive strategies and positive adjustment.

Locus of control

Locus of control (LOC) is described as an individual's expectancy that an outcome will predict behaviour in a given circumstance. Individuals with an internal LOC have the expectancy that their behaviours affect outcomes. Chung et al.16 examined the role of LOC in explaining individual differences in psychological adjustment. A sample of SCI patients (people with Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) and people with partial PTSD) were compared with healthy controls. Participants were then assigned to groups according to individual variations in LOC: internal, external control (powerful others) and chance. It was found that PTSD was associated with membership to the ‘external LOC’ group and also to health-related problems. These findings were not replicated in those patients with partial PTSD. These findings suggest that internal LOC may help the individual adjust to their injury by applying personal meaning and a sense of responsibility for ones situation.

Purpose in life

Thompson et al.17 looked at the existential construct of ‘Purpose in life’ in examining mediating effects on adjustment to spinal injury. This construct aims to attach meaning to life through environmental, social and inner worlds. Purpose in life was suggested as mediating the relationship between personality traits and LOC, and an integral factor in the adjustment process. Results of this study found purpose in life to have a direct influence on adjustment and support its role in mediating the effects of personality and LOC on adjustment.

Coping and pain

Raichle et al.18 looked at coping strategies, social support, pain beliefs and mental health when investigating biopsychosocial aspects of pain. In a sample of 157 patients, they found those with an external LOC and a tendency to catastrophize experienced more pain interference and decreased mental health well-being. In addition, those with a tendency to catastrophize were more likely to have solicitous social support and a lower score for perceived social support.

Wollaars et al.19 found that internal control of pain, coping, reduced degree of catastrophizing, higher lesion and non-traumatic onset of SCI were found to be associated with less pain experience. Variations in coping were linked to the appraisal of SCI (that is, helplessness and catastrophizing), acceptance of the injury, greater anger levels and higher depression levels. Quality of life and pain were also found to be related to psychological factors, most significantly ‘catastrophizing’ and ‘helplessness’. Overall, psychological factors were found to explain a large proportion of the variance in pain intensity, mainly through ‘catastrophizing’ and internal pain control.

The study presents support for the mediating effect of psychological factors (pain control, coping and catastrophizing) in pain intensity, reflecting individual differences in pain control. The inclusion of psychological variables helps contribute to a relationship between pain intensity and depression. However, the use of cross-sectional studies prevents the ability to infer causation and there may also be biased results because of the self-report method employed.

Coping and social participation

A model of social reintegration was examined using a South Korean sample of 145 people with SCI.20 Structural equation modelling assessed the direct and indirect effects of self-esteem, social barriers, physical function, family support, informational support, perceived stress and coping strategies (emotion-focused and problem-focused) on social reintegration and found to account for 65% of the variance. Interestingly, emotion-focused coping was found to have the most influence, thus emphasizing the important role of coping strategies to achieve adaptation. These findings are contrary to earlier research that finds problem-focused coping strategies to be more effective in overall adjustment. The authors suggest the shift in effectiveness of coping strategies may be because of the extensive time since injury of the sample, and supports the arguments for longitudinal research when assessing change in coping strategies.

The authors further propose that emotion-focused strategies may be employed when managing difficult and uncontrollable aspects of ones life. The need to employ these strategies, in turn, may explain the motivation to engage in social activities as distraction techniques and to increase mood levels. Significant predictors of social reintegration were found to be family and informational support, perceived stress and presence of social barriers. The role of appraisals in adjustment were also addressed in this study, as findings suggested those who experienced stress were found to perceive their SCI as more challenging and threatening. This provides further support for the mediating effect of appraisals in the relationship between coping strategies and psychological adjustment to SCI.

Conclusion

Much of the new literature supports the research originally reported by Galvin and Godfrey7 and reiterates the large contribution coping strategies and appraisals make to the explanation of variance in psychological adjustment.

A general criticism of the body of research is the continued use of correlational data from which one cannot infer causation. Attempts have been made to provide longitudinal research; however, more are required to assess the stability of coping strategies and to establish whether predictions can be made from early assessments.

Efforts have been made to assess coping strategies specifically to the event of an SCI; the development of a disability specific appraisal scale13 may now provide further information as to its impact on long-term adjustment.

The efficacy of cognitive-behavioural programmes when addressing adjustment difficulties will require future comparison of individual and group treatments. This method will allow researchers to assess the underlying mechanisms responsible for the psychological changes reported.

To establish particular coping strategies unique to the SCI population, future research may focus on the types of coping strategies used in able-bodied persons and compare these methods to those with an SCI. This may highlight specific coping strategies adaptive for those with SCI and which can be targeted during rehabilitation programmes.

References

Kennedy P, Lude P, Taylor N . Quality of life, social participation, appraisals and coping post spinal cord injury: a review of four community samples. Spinal Cord 2006; 44: 95–105.

Kennedy P, Duff J, Evans M, Beedie A . Coping effectiveness training reduces depression and anxiety following traumatic spinal cord injuries. Br J Clin Psychol Med Settings 2003; 12: 93–98.

Charlifue SW, Gerhart KA . Behavioural and demographic predictors of suicide after traumatic spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1991; 72: 488–492.

Macleod AD . Self neglect of spinal cord patients. Paraplegia 1988; 26: 340–349.

Lazarus RS, Folkman S . Stress, Appraisal, Coping. Springer: New York, 1984.

Pollard C, Kennedy P . A longitudinal analysis of emotional impact, coping strategies and post traumatic growth following spinal cord injury: a ten year review. Br J Health Psychol 2007; 12: 347–362.

Galvin LR, Godfrey HPD . The impact of coping on emotional adjustment to spinal cord injury (SCI): review of the literature and application of a stress appraisal and coping formulation. Spinal Cord 2001; 39: 615–627.

Elfström ML, Kreuter M, Rydén A, Persson LO, Sullivan M . Linkages between coping and psychological outcome in the spinal cord lesioned: development of SCL-related measures. Spinal cord 2002; 40: 23–29.

Kinder RA . Psychological hardiness in women with paraplegia. Rehabil Nurs 2005; 30: 68–72.

Hampton NZ . Subjective well-being among people with spinal cord injuries: the role of self-efficacy, perceived social support, and perceived health. Rehabil Couns Bull 2004; 48: 31–37.

Kennedy P, Taylor NM, Duff J . Characteristics predicating effective outcomes after coping effectiveness training for patients with spinal cord injuries. J Clin Psychol Med Settings 2005; 12: 93–98.

Kennedy P, Evans M, Sandhu N . Psychological adjustment to spinal cord injury: the contribution of coping, hope and cognitive appraisals. Psychol Health Med 2009; 14: 17–33.

Dean R, Kennedy P . Measuring appraisals following acquired spinal cord injury: a preliminary psychometric analysis of the appraisals of disability: primary and secondary scale (ADAPSS). Rehab Psychol 2009; 54: 222–231.

Buunk AP, Zurriaga R, González P . Social comparison, coping and depression in people with spinal cord injury. Psychol Health 2006; 21: 791–807.

Lustig DC . The adjustment process for individuals with spinal cord injury: the effect of perceived pre-morbid sense of coherence. Rehabil Counsel Bull 2005; 48: 146–156.

Chung MC, Preyeza E, Papandreou K, Prevezas N . Spinal cord injury, post traumatic stress and locus of control among the elderly: a comparison with young and middle aged patients. Psychiatry 2006; 69: 69–80.

Thompson NJ, Coker J, Krause JS, Henry E . Purpose in life as a mediator of adjustment in spinal cord injury. Rehabil Psychol 2003; 48: 100–108.

Raichle KA, Hanley M, Jenson MP, Cardenas DD . Cognitions, coping and social environment predict adjustment to pain in spinal cord injury. J Pain 2007; 8: 718–729.

Wollaars MM, Post MWM, van Asbeck FWA, Brand N . Spinal cord injury pain: the influence of psychologic factors and impact on quality of life. Clin J Pain 2007; 23: 383–391.

Song HY . Modelling social integration in patients with spinal cord injury. Disabil Rehabil 2005; 27: 131–141.

Acknowledgements

We thank Emilie Smithson for her help preparing this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chevalier, Z., Kennedy, P. & Sherlock, O. Spinal cord injury, coping and psychological adjustment: a literature review. Spinal Cord 47, 778–782 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2009.60

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2009.60

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

The contribution of bio-psycho-social dimensions on sexual satisfaction in people with spinal cord injury and their partners: an explorative study

Spinal Cord Series and Cases (2022)

-

Does the Danish version of the Spinal Cord Lesion-related Coping Strategies Questionnaire measure what we think it measures? A triangulated mixed-methods validation approach

Spinal Cord (2022)

-

Development of a Programme Theory for Early Intervention Vocational Rehabilitation: A Realist Literature Review

Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation (2021)

-

Use of Appraisals of DisAbility Primary and Secondary Scale-Short Form (ADAPSS-sf) in individuals with pediatric-onset spinal cord injury

Spinal Cord (2020)

-

Peer mentorship for adults with spinal cord injury: a static group comparison between mentees and non-mentees’ reported coping strategies

Spinal Cord (2018)