Abstract

This study aims to investigate the role of personality traits and subjective exposure experiences in posttraumatic stress disorder and depression symptoms. In Qingchuan, 21,652 children aged 7 to 15 years were assessed using face-to-face interviews one year after the Wenchuan earthquake in China. The Junior Eysenck Personality Questionnaire, a modified earthquake exposure scale, the UCLA Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Reaction Index (adolescent), and the Adolescent Depression Inventory were used to assess personality characteristics, trauma experiences, posttraumatic stress disorder and depression symptoms, respectively. The measurement was completed with 20,749 children. After adjusting for other factors by multinomial logistic regression analysis, neuroticism, having felt unable to escape from the disaster and having been trapped for a longer time were risk factors of posttraumatic stress disorder and depression symptoms. Socialization was a protective factor of them. Having felt extreme panic or fear was a risk factor of posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms. For depression symptoms, introversion and psychoticism were risk factors, and extraversion was a protective factor. This study was conducted with the largest representative sample of child survivors of a natural, devastating disaster in a developing country. These results could be useful for planning psychological intervention strategies for children and for influencing further research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

On May 12, 2008, a devastating earthquake measuring 8.0 on the Richter scale struck southwestern China, with the epicentre located in the Yingxiu town of Wenchuan County, Sichuan province1. It was reported that 69,195 people died, 374,177 people were injured, and 18,403 people went missing2. These losses may have caused the onset of psychiatric disorders for the survivors. Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD)—a trauma- and stressor-related disease—and depression, two of the most common psychiatric disorders observed among earthquake survivors, may surface weeks or months after traumatic events and often persist for years3. According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth edition (DSM-5), the diagnostic criteria of PTSD among school-aged children (older than 6 years) and young adolescents is the same as that of adults; however, the symptomatology of PTSD presented among children and adolescents may show increased arousal and persistent negative emotional states, which differs from that of adults4,5.

Personality traits determine the variation in typical reactions to the environment. That is, even when individuals experience the same trauma, their responses can vary because of personality traits. These traits are one reason why many people might experience trauma, but only a few develop PTSD6. Individual traits affect the development of PTSD by shaping cognitive processes, coping strategies and interaction with social support processes7,8,9. In predicting PTSD, the neuroticism trait is considered the most important personality dimension as it has been found to be robustly related to many mental disorders10. This trait, characterised by a presentation of negative emotional responses to threat, frustration or loss, overlaps specific aspects with arousal symptoms. This content-overlap is why neuroticism is considered a vulnerability factor of PTSD11,12. Extraversion, characterised by being outgoing, social, talkative, and having high positive affect, is associated with social support when detects the relationship between extraversion and PTSD13,14. Extraversion has been addressed by many researchers as negatively connected with PTSD; however, other researchers have failed to replicate this assertion15.

However, the above studies have been pertinent to adults, and the majority of the studies have ignored the impact of other personality traits (e.g., psychoticism). It has not yet been determined what role personality traits play in PTSD or depression symptoms among children after a catastrophe when primary personality traits are included and other risk factors are controlled16.

Another critical cluster of risk factors associated with PTSD in children is trauma exposure experiences that can be divided into two categories: objective (e.g., losing a family member, injury) and subjective (e.g., the experience of intense fear, helplessness, or horror)17,18. The former experiences have been found in many studies to have a consistent positive relationship with the incidence of PTSD19,20; by contrast, the latter experiences have been reported in only a few studies21,22. Notably, a meta-analysis has discovered that subjective exposure experiences are high-risk factors of PTSD, where as objective experiences appear only as small- to medium-risk factors. Research has shown mixed findings about the relationship between subjective characteristics and depression22; therefore, research should put additional emphasis on subjective trauma characteristics18.

Because of high comorbidity (varying from 20 to 45%), depression symptoms are strongly inter-correlated with PTSD after catastrophes23,24,25,26. Depression shares some risk factors with PTSD symptoms (e.g., neuroticism, objective trauma experiences)10,27, but some factors still show mixed findings (e.g., extraversion)28,29. However, with changes in the maturation process from child to adult, these factors might lead to a different impact of depression among children, which is not often reported. Therefore, the impact of these factors on depression among children should be studied further. Compared with the experience of PTSD on its own, patients with PTSD and depression present more severe symptoms, lower executive function and worse prognosis and often require different treatment strategies30,31,32. Despite these different manifestations with the presence of comorbidity, only a few studies have focused on the predictors of comorbid PTSD and depression as a separate entity from PTSD, with even fewer studies among children33.

It is notable that very little research on PTSD or depression has been conducted with large samples after a catastrophe, and the baseline of stress reactions that develops naturally among children in developing countries after a catastrophe has not been applied. Moreover, some non-psychological risk factors of PTSD or depression, such as sex, age, earthquake severity and distance to the epicentre, have been previously reported by many researchers20,24,34. Therefore, it is necessary to control for these non-psychological confounding risk factors. Finally, better understanding of the questions mentioned above could help us screen affected children in a timelier manner and provide some useful information for psychological prevention through which we can ultimately reduce the suffering of affected children. Given these reasons, we aimed to conduct a survey among child survivors to explore the role of primary personality traits and subjective exposure experiences (under the control of other risk factors) in PTSD and depression symptoms and offer a baseline for the stress reactions of children after a disaster. We hypothesised that personality traits and subjective exposure experiences are vital risk factors of PTSD and depression symptoms, even when controlling for other risk factors. Reducing the suffering of these children is our ultimate interest. We hope to do this by identifying susceptible children, providing useful information for following up on the affected children, and providing applications for these results in clinical practice.

Results

Demographic characteristics

Of the 21,652 participants, 20,749 (95.8%) children finished the measurement. Table 1 presents the demographics, personality characteristics, earthquake exposure experiences, and mental health outcomes of the children. The mean and median age of the children who finished the assessment (N = 20,749) was 11.7 (SD = 2.3) and 12 (IQR: 10, 12, 14), respectively. The majority of them were of Han nationality and from rural areas. In total, the prevalence of PTSD and depression symptoms was 19.2% (95% CI: 18.7-19.7) and 31.2%, (95% CI: 30.6–31.8), respectively. The prevalence of comorbidity was 11.7% (95% CI: 11.3–12.1), and 61% of those with PTSD suffered depression one year after the earthquake.

Correlations of Variables

The Spearman correlation coefficients presented in Table 2 indicated that although some of these variables were correlated, the relationships were weak (γ < 0.3), except for the relationship between having a close family member or friend injured and PTSD or depression symptoms.

Risk Factors of PTSD and Depression

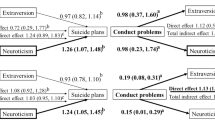

After controlling for confounding factors, the risk factors of only PTSD symptoms were neuroticism and three subjective exposure factors, including having felt unable to escape from the disaster, having experienced extreme panic or fear and having been trapped for a longer time. Socialization and stability were the protective factors (Table 3).

Adjusting for confounding factors, the risk factors of only depression symptoms were neuroticism, introversion, psychoticism, and two subjective exposure experiences, including having felt unable to escape from the disaster and having been trapped for a longer time. Socialization and extraversion were the protective factors (Table 3).

After adjusting for confounding factors, children who developed PTSD with comorbid depression symptoms were more likely to have psychoticism, extraversion, and introversion traits, have been injured, and have felt that one’s own or a family member’s life was in danger. These risk factors, however, did not apply to only PTSD symptoms (Table 3).

Discussion

This study was conducted with the largest representative sample to date of child survivors from a natural, devastating disaster in a developing country. While controlling for other risk factors, this study detected the influence of all primary personality traits and subjective exposure experiences on PTSD and depression symptoms. Before this survey, the local children had little opportunity to receive extensive and systemic psychological interventions due to their harsh natural environment and adverse traffic conditions. Accordingly, their post-earthquake stress reaction may be more likely to develop along a natural psychological process, which could in turn establish a baseline of stress reaction among children after a disaster. Since this survey was conducted one year after the earthquake, these results reflected a mid- to long-term impact of the disaster on children.

The results of this study indicated that PTSD and depression symptoms were common among children one year after the earthquake. The prevalence of PTSD has varied widely in previous reports20, even for the same earthquake–the Wenchuan earthquake35. In this study, the prevalence of PTSD symptoms (19.2%) was in line with many previous studies36,37. The prevalence of depression varied widely from approximately 13% to 76% after disastersworldwide34,38,39,40 and from approximately 19% to 45% after the Wenchuan earthquake41,42,43,44. The result of this study (31.2%) was reported to be in accordance with other research conducted after an earthquake with a similar magnitude (31%)24, whereas other studies reported approximately 13%20,45. We attributed the much lower prevalence of PTSD and depression to the lower earthquake severity (5.9 magnitude) in latter studies. The prevalence of comorbidity was high, which was in accordance with previous studies.

The neuroticism trait was a risk factor of only PTSD symptoms, and stability was its protective factor after controlling for other confounders. In the presence of neuroticism, children were 8 times more likely to suffer PTSD symptoms than those with a stability trait. Notably, in the presence of high neuroticism, the risk for children to suffer a co-occurrence of PTSD and depression symptoms was 40 times more than for children with the stability trait. These results further confirmed the findings of previous studies that neuroticism has played an important role in predicting the probability of PTSD due to its negative mood feature46,47. Moreover, the overlapping aspect of neuroticism and arousal symptoms might contribute to its effect on elevating the risk of PTSD48. Based on the results of this study, we recommend that future studies evaluate the neurotic personality as an essential risk factor for PTSD among children.

Extraversion was not associated with PTSD among children, but it was a protective factor of the comorbidity of PTSD and depression symptoms. Unlike neuroticism, extraversion was less consistent with PTSD in previous research. Some researchers revealed that extraversion had no relationship with PTSD9,49, whereas a negative relationship was reported in other studies13,50. According to the results of this study, whether the impact of comorbid depression is controlled may explain the difference, which implies the critical role of comorbid depression in detecting the impact of extraversion on PTSD. Psychoticism, reported as a risk factor in only a few earlier studies51,52, was rarely identified as a risk factor for PTSD in this study, unless PTSD appeared with comorbid depression symptoms. Accordingly, future studies should consider the impact of comorbid depression.

In this study, subjective exposure experiences—feeling unable to escape from the disaster, experiencing extreme panic or fear and being trapped for a longer time—were identified as risk factors for PTSD, which was similar to the findings of other researchers53,54. Another study showed that children who experienced extreme panic or fear had a 9-timehigher risk for PTSD symptoms than children without this experience22, whereas our result only showed a two-time higher risk. We believe that controlling the impact of personality traits in our study could explain the lowered risk. Inability to escape a traumatic stressor—that is, the uncontrollability of a stressor—has been found to be a crucial risk factor for PTSD in trauma survivors55, and a perceived threat is very likely to be linked to the onset of PTSD. In addition, research conducted on earthquake survivors has shown that fear or a sense of threat during earthquake exposure is a strong predictor of PTSD symptoms, explaining a greater proportion of variance than objective trauma severity variables, such as having been trapped under rubble or being injured20,56,57,58. The objective exposure experiences (e.g., the severity of the natural disaster or being injured) cannot be altered after the disaster, but the subjective experiences can be changed by effective psychological intervention. Therefore, future psychological interventions should focus on ameliorating children’s subjective trauma characteristics, which could, in turn, reduce the experience of PTSD symptoms. Future research should pay more attention to subjective exposure experiences.

For depression symptoms in the absence of comorbid PTSD symptoms, neuroticism could increase the risk of depression in children, consistent with the findings of earlier studies59. Moreover, we found that children with the neurotic trait were approximately 11 times more likely to suffer depression symptoms than those with the stability trait.

Unlike PTSD, extraversion and introversion were the protective factor and the risk factor, respectively, of only depression symptoms in this study. Lower extraversion was reported to relate to higher depression rates in adults60,61, which was also discovered among children in this study after controlling for other risk factors. However, a lack of this association was reported in another study of adolescents29. We attribute the opposite result to the different assessments used to measure extraversion. Extraversion is composed of four major facets, and some questionnaires assess only one or two primary facets62,63. This difference highlights the fact that various facets of extraversion may show somewhat divergent associations with depression. Therefore, in the future, research should focus on the impact of a particular facet on depression instead of the whole extraversion dimension. These outcomes regarding personality traits could be beneficial for formulating appropriate psychological interventions to lessen depression symptoms.

One subjective exposure experience—having felt unable to escape from the disaster—which was found to be a risk factor of depression symptoms in early research64, was replicated in this study, although other studies did not identify this association22. The difference in sample size and whether the research studies controlled for the other risk factors might account for the mixed findings.

This study had some limitations. First, this was a cross-sectional investigation, whereas a long-term follow-up study may be more worthwhile. Second, instead of clinician-verified diagnoses of PTSD and depression, symptoms of PTSD and depression were screened only by the instruments; however, these instruments have been widely used for research and have good reliability and validity, which guaranteed the outcomes of this study. Third, there could be some bias in recalling subjective experience a year after the disaster. However, the questionnaire was completed by children without the parent or guardian in close proximity, which might lower the bias to some degree. Finally, this research simultaneously measured children’s personality characteristics and symptoms post-earthquake, which could mean that the earthquake or symptoms themselves may have had an influence on the development of personality traits.

Methods

Procedure and Samples

To establish a baseline for stress reactions that develop as a result of natural processes, Qingchuan, Sichuan province, in China (a region with the 10th strongest seismic intensity and a population of 248,000 encompassing an area of 3,271 square kilometres) was selected as the survey site (Fig. 1). After the disaster, extensive and systemic psychological interventions were minimally provided for the children in Qingchuan until the survey could be implemented because of the harsh natural environment and poor traffic conditions. This ensured a naturally developing process of the children’s post-earthquake stress reaction. The participants were recruited from schools in Qingchuan approximately one year after the Wenchuan earthquake, from May to July 2009. The timing for evaluating post-earthquake stress reactions is crucial, because within one year after the disaster, the manifestations in child survivors may either vanish or become more permanent65,66.

There were 21,695 children aged 7–15 years old in Qingchuan. Of these children, 99.8% (21,652) of those who experienced the Wenchuan earthquake, participated this survey, and 95.6% (20,749) finished the measurement. The survey was conducted by trained interviewers through face-to-face interview. The interviewers included psychiatrists, psychologists, psychiatric nurses, and social workers. Participants were interviewed in school without the parent or guardian in close proximity; thus, each child responded to all questions without consultation or interference. All children were asked for consent, and their parents or guardians provided informed consent to participate.

This study was considered the foundation for applying further appropriate psychological interventions targeted at child survivors who were at elevated risk of developing or experiencing either PTSD or depression symptoms in Qingchuan. Children in need of mental health support were referred to available mental health services after this survey. Because of the seriousness of the psychological stress-related disorder in children post disaster, the study was conducted under the stringent supervision of the local education department. When the research was initiated, West China Hospital did not require ethics approval for research that involved secondary data analyses. To ensure compliance with ethics requirements, the present research was reviewed and received ethics approval from the Medical Ethics Committee of West China Hospital on 2 April 2015. The survey was totally performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Instruments

An earthquake exposure scale, which included 10 yes-and-no questions, was used to evaluate the children. It was adapted from prior earthquake exposure scales based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th ed., text rev.; DSM-IV-TR; American Psychiatric Association, 2000) A-1 and A-2 criteria for PTSD67,68 and was modified according to earthquake trauma experiences. The instrument contained five items evaluating subjective factors (i.e., having experienced extreme panic or fear, having felt unable to escape from the disaster, having felt others’ panic, having been trapped for a longer time, having felt one’s own or a family member’s life to be in danger).

The adolescent version of the UCLA PTSD Reaction Index, which is widely used to assess traumatised children following major disasters and catastrophic violence69, was used to evaluate symptoms of PTSD. The index contained 20 items with a 5-point scale ranging from 0 (never) to 4 (most of the time) and was translated into Chinese. A total score of 36 or higher was used to classify a child as having PTSD symptoms70. The internal consistency Cronbach’s α was 0.91 for the total scale, 0.89 for the factor of re-experiencing/avoidance/increased arousal symptoms, and 0.82 for numbness/pessimism symptoms, respectively70,71,72.

Symptoms of depression were assessed by the Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI), a self-report measure designed for children ages 6 to 17 years73. This questionnaire contained 27 items and was used to rate the frequency of depression symptoms over the previous 2 weeks on a 3-point scale (2 = most of the time,1 = sometimes, 0 = never)and then was translated into Chinese. With excellent test-retest reliability (0.75) and good internal consistency (0.82) corresponding to the DSM-IV-TR symptom groups, the questionnaire has been proven to be a valid tool for the assessment of depression symptoms in adolescents74,75. A score of 20 or higher was used to classify an adolescent as having depression symptoms76.

The Junior Eysenck Personality Questionnaire (JEPQ), a self-report questionnaire for children aged 7 to 1577, was translated into Chinese and modified 30 years ago78,79. It was used to assess personality characteristics in this study, whereas most previous research has included only one or two subscales. Since the Chinese norm was compiled, the JEPQ has been widely used in China80,81. The Chinese version of the JEPQ comprises88 yes-and-no items (yes = 1, no = 0) and five levels of four subscales: psychoticism (P), extraversion (E), neuroticism (N), and lie (L). Its test-retest reliability was 0.65, 0.86, 0.72 and 0.62 for the P, E, N and L subscales, respectively. For example, the E subscale was divided into five levels: introversion (T < 38.5); moderate introversion (38.5 ≤ T < 43.3); intermediate extraversion(43.3 ≤ T ≤ 56.7); moderate extraversion (56.7 < T ≤ 61.5); and extraversion (T > 61.5). The other subscales were divided similarly.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed by the Statistical Product and Service Solutions 16.0 (SPSS Version 16.0). First, frequencies of all variables and prevalence were calculated. The age variable was described by the median and the quartile, and divided into two groups (7- to 11-year-olds and 12- to 15-year-olds). Second, spearman correlation was used to assess the potential inter-variable associations of all variables. Finally, multinomial logistic regression analysis was used to identify the role of personality traits and subjective exposure experiences under the control of other factors. The dependent variable was divided into four groups: (a) without PTSD or depression symptoms; (b) only PTSD symptoms; (c) only depression symptoms; and d) PTSD comorbid depression symptoms. Group a) was used as a reference category for the dependent variable. This procedure yielded odd ratios with 95% confidence intervals for each variable. All the demographics, personality traits, and earthquake exposure experience factors were entered into the equation as independent factors. Female, national minority, younger age (7–11 years), living in a rural area, and the intermediate type of each personality dimension was served as the reference categories for gender, ethnic group, age, residence, and personality variables, respectively. The answer “no” was served as the reference category for the other dichotomous variables. All tests were two-tailed, and those that had p values of 0.05 or lower were treated as statistically significant in all data analyses.

Data availability statement

The use of data will be confined to the study group, but potential collaborators or requests for data can be submitted to the corresponding author.

References

Stone, R. Sichuan disaster. Landslides, flooding pose threats as experts survey quake’s impact. Science. 320, 996–997 (2008).

UNICEF. UNICEF External Situation Report China Earthquake - 01 Jul 2008. http://www.reliefweb.int/rw/rwb.nsf/db900SID/EGUA-7G6Q2T?OpenDocument 08/12/2016 (2008).

Yule, W. Posttraumatic stress disorder in the general population and in children. J Clin Psychiatry. 62(Suppl 17), 23–28 (2001).

Association, A. P. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. (Washington, DC, 2013).

Scheeringa, M. S., Zeanah, C. H. & Cohen, J. A. PTSD in children and adolescents: toward an empirically based algorithma. Depress Anxiety. 28, 770–782 (2011).

Mischel, W. Toward an integrative science of the person. Annual review of psychology. 55, 1 (2004).

Swickert, R. J., Rosentreter, C. J., Hittner, J. B. & Mushrush, J. E. Extraversion, social support processes, and stress. Personality and Individual Differences. 32, 877–891 (2002).

Kindt, M. & Engelhard, I. M. Trauma processing and the development of posttraumatic stress disorder. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 36, 69–76 (2005).

Lawrence, J. W. & Fauerbach, J. A. Personality, coping, chronic stress, social support and PTSD symptoms among adult burn survivors: a path analysis. J Burn Care Rehabil. 24, 63–72; discussion 62 (2003).

Lahey, B. B. Public health significance of neuroticism. Am Psychol. 64, 241–256 (2009).

R. Goldberg, L. The structure of phenotypic personality traits. Vol. 48 (1993).

Eysenck, H. J. & Eysenck, M. W. Personality and individual differences. A natural science approach. (Plenum, 1985).

Shakespeare-Finch, J., Gow, K. & Smith, S. Personality, Coping and Posttraumatic Growth in Emergency AmbulancePersonnel. Traumatology. 11, 325–334 (2005).

Cao, X., Jiang, X., Li, X., Hui Lo, M. C. & Li, R. Family functioning and its predictors among disaster bereaved individuals in China: eighteen months after the Wenchuan Earthquake. PLoS One. 8, e60738 (2013).

Paris, J. Predispositions, personality traits, and posttraumatic stress disorder. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 8, 175–183 (2000).

Warner, L. M., Gutierrez-Dona, B., Villegas Angulo, M. & Schwarzer, R. Resource loss, self-efficacy, and family support predict posttraumatic stress symptoms: a 3-year study of earthquake survivors. Anxiety Stress Coping. 28, 239–253 (2015).

Perrin, S., Smith, P. & Yule, W. Practitioner review: The assessment and treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder in children and adolescents. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 41, 277–289 (2000).

Trickey, D., Siddaway, A. P., Meiser-Stedman, R., Serpell, L. & Field, A. P. A meta-analysis of risk factors for posttraumatic stress disorder in children and adolescents. Clinical Psychology Review. 32, 122–138 (2012).

Matsumoto, K., Sakuma, A., Ueda, I., Nagao, A. & Takahashi, Y. Psychological trauma after the Great East Japan Earthquake. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 70, 318–331 (2016).

Roussos, A. et al. Posttraumatic stress and depressive reactions among children and adolescents after the 1999 earthquake in Ano Liosia, Greece. Am J Psychiatry. 162, 530–537 (2005).

Vernberg, E. M., Silverman, W. K., La Greca, A. M. & Prinstein, M. J. Prediction of posttraumatic stress symptoms in children after hurricane Andrew. J Abnorm Psychol. 105, 237–248 (1996).

Thienkrua, W. et al. Symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder and depression among children in tsunami-affected areas in southern Thailand. JAMA. 296, 549–559 (2006).

Goenjian, A. K. et al. Psychiatric comorbidity in children after the 1988 earthquake in Armenia. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 34, 1174–1184 (1995).

Ekşi, A. et al. Risk factors for the development of PTSD and depression among child and adolescent victims following a 7.4 magnitude earthquake. International Journal of Psychiatry in Clinical Practice. 11, 190–199 (2007).

Campbell, D. G. et al. Prevalence of depression-PTSD comorbidity: implications for clinical practice guidelines and primary care-based interventions. Journal of general internal medicine. 22, 711–718 (2007).

Blanchard, E. B., Buckley, T. C., Hickling, E. J. & Taylor, A. E. Posttraumatic stress disorder and comorbid major depression: is the correlation an illusion? Journal of anxiety disorders. 12, 21–37 (1998).

Vinkers, C. H. et al. Stress Exposure Across The Life Span Cumulatively Increases Depression Risk And Is Moderacted By Neuroticism. Depression and Anxiety. 31, 737 (2014).

Karsten, J. et al. The state effect of depressive and anxiety disorders on big five personality traits. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 46, 644–650 (2012).

Uliaszek, A. A. et al. The Role of Neuroticism and Extraversion in the Stress-Anxiety and Stress-Depression Relationships. Anxiety Stress & Coping, Stress, 363–381 (2010).

Johnsen, G., Kanagaratnam, P., Nordling, T., Wilberg, C. & Asbjørnsen, A. Psychophysiological responses to an executive task in refugees with chronic PTSD and comorbid depression. (2016).

Olff, M., Polak, A. R., Witteveen, A. B. & Denys, D. Executive function in posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and the influence of comorbid depression. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory. 112, 114–121 (2014).

Tural, U., Onder, E. & Aker, T. Effect of depression on recovery from PTSD. Community mental health journal. 48, 161–166 (2012).

Thabet, A. A., Abed, Y. & Vostanis, P. Comorbidity of PTSD and depression among refugee children during war conflict. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 45, 533–542 (2004).

Salcioglu, E. & Basoglu, M. Psychological effects of earthquakes in children: prospects for brief behavioral treatment. World J Pediatr. 4, 165–172 (2008).

Zhou, X. et al. Prevalence and risk factors of posttraumatic stress disorder among adult survivors six months after the Wenchuan earthquake. Compr Psychiatry. 54, 493–499 (2013).

Dai, W. et al. The incidence of posttraumatic stress disorder among survivors after earthquakes:a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry. 16, 188 (2016).

Fan, F., Zhang, Y., Yang, Y., Mo, L. & Liu, X. Symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder, depression, and anxiety among adolescents following the 2008 Wenchuan earthquake in China. J Trauma Stress. 24, 44–53 (2011).

Pfefferbaum, B. Posttraumatic stress disorder in children: a review of the past 10 years. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 36, 1503–1511 (1997).

Lonigan, C. J., Phillips, B. M. & Richey, J. A. Posttraumatic stress disorder in children: diagnosis, assessment, and associated features. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 12, 171–194 (2003).

Cook-Cottone, C. Childhood posttraumatic stress disorder: Diagnosis, treatment, and school reintegration. School Psychology Review. 33, 127–139 (2004).

Ying, L. H., Wu, X. C., Lin, C. D. & Chen, C. Prevalence and predictors of posttraumatic stress disorder and depressive symptoms among child survivors 1 year following the Wenchuan earthquake in China. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 22, 567–575 (2013).

Ye, Y., Fan, F., Li, L. & Han, Q. Trajectory and predictors of depressive symptoms among adolescent survivors following the Wenchuan earthquake in China: a cohort study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 49, 943–952 (2014).

Ran, M. S. et al. Risk factors of suicidal ideation among adolescents after Wenchuan earthquake in China. Asian J Psychiatr. 13, 66–71 (2015).

Pan, X. et al. Symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder, depression, and anxiety among junior high school students in worst-hit areas 3 years after the Wenchuan earthquake in China. Asia Pac J Public Health. 27, NP1985–1994 (2015).

Goenjian, A. K. et al. Longitudinal study of PTSD, depression, and quality of life among adolescents after the Parnitha earthquake. Journal of Affective Disorders. 133, 509–515 (2011).

Lauterbach, D. & Vrana, S. The relationship among personality variables, exposure to traumatic events, and severity of posttraumatic stress symptoms. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 16, 29–45 (2002).

O’Toole, B. I., Marshall, R. P., Schureck, R. J. & Dobson, M. Posttraumatic stress disorder and comorbidity in Australian Vietnam veterans: risk factors, chronicity and combat. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 32, 32–42 (1998).

Engelhard, I. M., van den Hout, M. A. & Kindt, M. The relationship between neuroticism, pre-traumatic stress, and posttraumatic stress: a prospective study. Personality and Individual Differences. 35, 381–388 (2003).

Schnurr, P. P. & Vielhauer, M. J. Personality as a risk factor for PTSD. 191–222 (John Wiley, 1999).

Jaksic, N., Brajkovic, L., Ivezic, E., Topic, R. & Jakovljevic, M. The role of personality traits in posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Psychiatr Danub. 24, 256–266 (2012).

Holeva, V. & Tarrier, N. Personality and peritraumatic dissociation in the prediction of PTSD in victims of road traffic accidents. J Psychosom Res. 51, 687–692 (2001).

Casella, L. & Motta, R. W. Comparison of characteristics of Vietnam veterans with and without posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychol Rep. 67, 595–605 (1990).

Lubit, R., Rovine, D., DeFrancisci, L. & Eth, S. Impact of trauma on children. J Psychiatr Pract. 9, 128–138 (2003).

McDermott, B. M. & Palmer, L. J. Postdisaster emotional distress, depression and event-related variables: findings across child and adolescent developmental stages. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 36, 754–761 (2002).

Foa, E., Zinbarg, R. & Rothbaum, B. Uncontrollability and unpredictability in posttraumatic stress disorder: an animal model. Psychol Bull. 112, 218–238 (1992).

Başoğlu, M., Kilic, C., Salcioğlu, E. & M., L. Prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder and comorbid depression in earthquake survivors in Turkey: an epidemiological study. J Trauma Stress. 17, 133–141 (2004).

Başoğlu, M., Salcioğlu, E. & M., L. Traumatic stress responses in earthquake survivors in Turkey. J Trauma Stress. 15, 269–276 (2002).

Salcioglu, E., Basoglu, M. & Livanou, M. Posttraumatic stress disorder and comorbid depression among survivors of the 1999 earthquake in Turkey. Disasters. 31, 115–129 (2007).

Aldinger, M. et al. Neuroticism developmental courses - implications for depression, anxiety and everyday emotional experience; a prospective study from adolescence to young adulthood. BMC Psychiatry. 14, 210 (2014).

Spinhoven, P., Elzinga, B. M., Hemert, A. M. V., Rooij, M. D. & Penninx, B. W. A longitudinal study of facets of extraversion in depression and social anxiety. Personality & Individual Differences. 71, 39–44 (2014).

Kotov, R., Gamez, W., Schmidt, F. & Watson, D. Linking “big” personality traits to anxiety, depressive, and substance use disorders: a meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 136, 768–821 (2010).

Watson, D. & Clark, L. A. In Handbook of Personality Psychology (eds John Johnson & Stephen Briggs) 767–793 (Academic, 1997).

Watson, D., Gamez, W. & Simms, L. J. Basic dimensions of temperament and their relation to anxiety and depression: A symptom-based perspective. Journal of Research in Personality. 39, 46–66 (2005).

Wang, W. et al. Prevalence of PTSD and depression among junior middle school students in a rural town far from the epicenter of the Wenchuan earthquake in China. PLoS One. 7, e41665 (2012).

Yule, W. et al. The long-term psychological effects of a disaster experienced in adolescence: I: The incidence and course of PTSD. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 41, 503–511 (2000).

Bolton, D., O’Ryan, D., Udwin, O., Boyle, S. & Yule, W. The long-term psychological effects of a disaster experienced in adolescence: II: General psychopathology. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 41, 513–523 (2000).

Gurwitch, R. H. et al. When disaster strikes: responding to the needs of children. Prehosp Disaster Med. 19, 21–28 (2004).

Pynoos R, Schreiber M & A., S. In Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry Vol. 8 (Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2004).

Steinberg, A. M., Brymer, M. J., Decker, K. B. & Pynoos, R. S. The University of California at Los Angeles Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Reaction Index. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 6, 96–100 (2004).

Zhang, H. A followup study of child survivors of the 1999 Taiwan earthquake: Posttraumatic stress reactions and school-based intervention, Chang Gung University (2006).

Chen, S., Lin, Y. & H., T. Posttraumatic Stress Reactions in. Children and Adolescents One Year after the 1999 Taiwan Chi-Chi Earthquake. Journal of the Chinese Institute of Engineers. 25, 597–608 (2002).

Chen, S., Hung, F. & Y., L. In Proceedings of International Workshop on Annual Commemoration of Chi-Chi Earthquake Engineering. (eds Loh, C. H., & I. W. Liao) 318–331.

Compas, B. E., Ey, S. & Grant, K. E. Taxonomy, assessment, and diagnosis of depression during adolescence. Psychol Bull. 114, 323–344 (1993).

Chang, H. J., Yang, C. Y., Lin, C. R., Ku, Y. L. & Lee, M. B. Determinants of suicidal ideation in Taiwanese urban adolescents. J Formos Med Assoc. 107, 156–164 (2008).

David, Y. & X., L. Preliminary Use of the Children’s Depression Inventory in China. Chinese Mental Health Journal. 14, 225–227 (2000).

Hong, X., Liang, Y. & Z., W. Physical activity and its correlation with depression among high School Students in Nanjing. Chinese J School Health. 28, 1059–1061 (2007).

Claridge, G. Manual of the Eysenck personality questionnaire (junior and adult): H. J. Eysenck and Sybil Eysenck Hodder and Stoughton (1975). 47 pp., together with test blanks and scoring keys for junior and adult versions. Specimen set £1.80. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 15, 369–370 (1977).

Gong, Y. Eysenck Personality Questionnaire Revised in China. Psychological Science. 11–18 (1984).

Chen, Z. Item Analysis of Eysenck Personality Questionnaire. Acta Psychologica Sinica. 211–217 (1983).

Gong, Y. Use of the Eysenck Personality Questionnaire in China. Personality and Individual Differences. 5, 431–438 (1984).

Zhu, C. et al. Eysenck Personality Questionaire (Junior) Used in Chengdu. Journal of Sichuan University 14, 149–154 (1983).

Acknowledgements

National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Number: 81401132); Sichuan Provincial Science and Technology Support Program (Grant Number: 2014SZ0017). The authors are grateful to Professor S Chen and Professor M.Y Qian for their authorization of scales. Also we express thanks to X Zhao for assistance with data collection.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The corresponding authors had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. The corresponding author also was responsible for submitting a competing financial interests statement on behalf of all authors of the paper. Study concept and design: Jiajun Xu, Xiacan Chen and Junmei Hu. Data collection: Jiajun Xu, Xiacan Chen, Bin Li and Na Li. Analysis and interpretation of data: Xiacan Chen, Jiajun Xu. Drafting of the manuscript: Xiacan Chen and Jiajun Xu. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Junmei Hu, Wanjun Guo, Jun Zhang, Yanchun Yang and Maosheng Ran. All authors reviewed the manuscript. Obtained funding: Jiajun Xu.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, X., Xu, J., Li, B. et al. The Role of Personality and Subjective Exposure Experiences in Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Depression Symptoms among Children Following Wenchuan Earthquake. Sci Rep 7, 17223 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-17440-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-17440-9

This article is cited by

-

The role of trauma experiences, personality traits, and genotype in maintaining posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms among child survivors of the Wenchuan earthquake

BMC Psychiatry (2020)

-

Temporal Transitions in Patterns of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Depression Among Adolescents Following the Wenchuan Earthquake

Child Psychiatry & Human Development (2019)

-

Depression in Youth Exposed to Disasters, Terrorism and Political Violence

Current Psychiatry Reports (2019)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.