Abstract

Self-management is an established, effective approach to controlling asthma, recommended in guidelines. However, promotion, uptake and use among patients and health-care professionals remain low. Many barriers and facilitators to effective self-management have been reported, and views and beliefs of patients and health care professionals have been explored in qualitative studies. We conducted a systematic review and thematic synthesis of qualitative research into self-management in patients, carers and health care professionals regarding self-management of asthma, to identify perceived barriers and facilitators associated with reduced effectiveness of asthma self-management interventions. Electronic databases and guidelines were searched systematically for qualitative literature that explored factors relevant to facilitators and barriers to uptake, adherence, or outcomes of self-management in patients with asthma. Thematic synthesis of the 56 included studies identified 11 themes: (1) partnership between patient and health care professional; (2) issues around medication; (3) education about asthma and its management; (4) health beliefs; (5) self-management interventions; (6) co-morbidities (7) mood disorders and anxiety; (8) social support; (9) non-pharmacological methods; (10) access to healthcare; (11) professional factors. From this, perceived barriers and facilitators were identified at the level of individuals with asthma (and carers), and health-care professionals. Future work addressing the concerns and beliefs of adults, adolescents and children (and carers) with asthma, effective communication and partnership, tailored support and education (including for ethnic minorities and at risk groups), and telehealthcare may improve how self-management is recommended by professionals and used by patients. Ultimately, this may achieve better outcomes for people with asthma.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Self-management is an established, effective and guideline-recommended approach to controlling asthma.1 It has been defined by the US Institute of Medicine as “the tasks that individuals must undertake to live with one or more chronic conditions. These tasks include having the confidence to deal with medical management, role management and emotional management of their conditions”.2 With regard to asthma control, this encompasses adherence to treatment. Adherence enables individuals to self-manage their condition and is essential to the success of self-management interventions.3 Effective self-management has resulted in improved quality of life and reduced healthcare utilisation, days absent from work or school, and nocturnal asthma.4 However, despite effective medication being available, asthma is poorly controlled in over 50% of cases,5,6 and the promotion, uptake and use of self-management among people with asthma, carers of children with asthma, and healthcare professionals remain low.7,8,9 To maximise the benefits of self-management, barriers and facilitators to effective self-management (which may be encountered by the individual with asthma (or carer), the healthcare professional, or at the organisational level)10,11,12 need to be identified. Further, more effective treatment and management strategies are needed. Identification of the needs, beliefs, and behaviours of these individuals and organisational features12 can indicate where improvements should be focused to help groups of people least likely to benefit from existing self-management interventions, and potentially inform the design and implementation of future interventions.10

Quantitative reviews in this area have focused on identifying and comparing combinations of effective features of self-management interventions, and comparing methods of delivering and implementing these interventions.4,8,12,13,14,15,16,17,18 However, they contribute less to our understanding of the barriers and facilitators to self-management.5,15,16 Qualitative research, however, can provide in-depth information about behaviours, beliefs, emotions and relationships that may influence uptake of and adherence to self-management. Two qualitative reviews have synthesised the literature in this area.19,20 highlighted factors that can contribute to low acceptance of or adherence to self-management programmes for asthma, at the patient and programme level. They also identified the need for healthcare professionals to incorporate patient input in the development of treatment plans; to agree upon treatment goals; and to acknowledge patient knowledge of asthma based on personal experience. However, they were both relatively narrow in scope; the first review focused on adherence to medication, based on patient viewpoints only, and the second review focused specifically on barriers to action plan use. Thus, no qualitative review to date has encompassed the full range of barriers and facilitators to asthma self-management. The aim of our systematic review is to identify individual patient, professional and organisational barriers and facilitators to asthma self-management, by examining qualitative evidence from the perspectives of patients, carers and healthcare professionals.

Results

Study characteristics

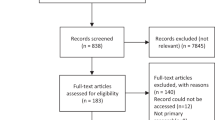

The search results (Fig. 1) identified 2784 papers, of which 127 were deemed potentially relevant. Following application of exclusion criteria and quality assessment, 56 papers were eligible for the review. The 56 papers included in the review were published between 1997 and 2017, although two thirds of this research was published within the latter 10 years, reflecting a growing interest in this area, particularly within the USA. The majority of the research was conducted in the USA (n = 23)21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43 or the UK (n = 12),11,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54 with fewer studies being conducted across the rest of the world: Australia (n = 6),55,56,57,58,59,60 Canada (n = 3),61,62,63 Taiwan (n = 3),64,65,66 Denmark (n = 2),67,68 Singapore (n = 2),69,70 Netherlands (n = 2),71,72 Germany (n = 1),73 New Zealand (n = 1),74 and Thailand (n = 1).75 Data collection methods primarily comprised interviews (n = 35)23,24,25,26,29,30,35,36,37,38,41,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,55,56,57,58,60,61,62,64,65,66,68,72,74,75 and focus groups (n = 21).11,22,28,31,33,34,39,40,42,43,45,46,47,58,59,63,67,69,70,71,73 A few alternative methods were also used: diary or journal data (n = 2),21,27 online free text responses (n = 1),54 and the recording of clinical consultations (n = 1).32 The following groups of participants were studied: adults with asthma (n = 25),21,22,23,24,25,32,35,38,39,40,41,43,44,49,50,54,55,56,57,59,60,61,62,63,73 children, adolescents and/or carers (n = 29),11,26,27,28,29,30,31,33,34,36,37,39,42,47,48,51,52,53,62,64,65,66,67,68,70,71,72,74,75 healthcare professionals (n = 9),11,31,32,39,46,52,63,69,74 and one study included school staff.31 There has also been a move over time to explore in more detail the views of minority ethnic and other at risk groups. These included African Americans (n = 6),33,34,35,37,38,43 South Asians (n = 2),44,45 Puerto Ricans (n = 1),28 Mexicans (n = 1),30 Latinos (n = 1),41 older adults (aged 50 and above; n = 1),57 those on a low income (n = 5),21,23,25,51,65 those from urban areas (n = 5),21,23,33,34,51 and those from rural areas (n = 2).25,42 Two studies focused on those with intellectual disabilities (n = 1),60 and low health literacy (n = 1).38 A subsection (n = 8) examined perspectives on use of various ways to deliver self-management interventions, such as within schools, or using mobile phones, patient advocates, pharmacist-delivered interventions, internet-delivered interventions, and by enhancing information given to HCPs before clinical conversations.21,25,31,32,47,58,67,68

Thematic synthesis

Thematic synthesis identified 11 main themes, within which analytic themes were identified that encompass the barriers and facilitators to asthma self-management found in this review. A diagram of the themes is presented in Fig. 2, and they are detailed in Tables 1–6. Barriers and facilitators to asthma self-management in relation to the themes are summarised below, and presented in Table 7.

The first theme, presented in Table 1, identified the need for a sense of partnership between the patient/carer and their healthcare professional. This theme was identified within only 26 (46%) of the included papers, but was expressed strongly in those papers. Facilitators identified by both patients and HCPs include the view that good communication based on mutual trust and respect gives patients and carers confidence in their understanding of asthma, and increases the likelihood of them adhering to self-management advice. Unfortunately, this was an area in which frustration was often expressed, and an absence of this partnership commonly reported, particularly by adolescents and young people, those with low health literacy or intellectual disabilities, and those from ethnic minorities. Patients and carers had specific expectations of their HCP, in relation to feeling listened to, being in partnership, and the need for consistent personalised advice and information. Indeed, a perceived lack of continuity in advice could lead to the belief that care and treatment is ineffective, and the decision not to comply with advice.

The next theme focused on patient and carer issues around medications, (Table 2) and was a dominant theme, reported within 39 (70%) of the included papers. Barriers, rather than facilitators, tended to be discussed within this theme, with 21 papers raising patient, child and carer concerns over the safety and side effects of asthma medicines. However, some studies did report facilitators in the form of strategies, particularly for teenagers and those with intellectual disabilities, who along with those from ethnic minorities, older adults, and other patients, tends to avoid ‘too much’ ‘toxic’ medication use due to fear of side effects, tolerance and addiction.

Other medication barriers included practical barriers, such as costs of medications, misunderstanding medication instructions and the inconvenience of remembering and administering medication, particularly for children and school staff during school hours. Some patients and carers experiment with action plans and timing and dosages of medication, which can cause symptoms to worsen. However, when done in collaboration with a HCP it can facilitate asthma self-management by increasing confidence. Some patients and carers had preferences for particular types of medication, including CAM use, which was considered mainly by women, and in combination with conventional medicines.

A need for more education regarding asthma and its management was also a dominant theme that was identified, being discussed in 40 (71%) of the papers (Table 3). With regards to barriers, many healthcare professionals feel they have insufficient training in action plan use. From the patient perspective, the understanding and awareness of asthma, asthma control and triggers, as well as an understanding of medication and appropriate use of medication appears to be a concern for most patients. This seemed to be relatively universal including among those with low health literacy or intellectual disabilities and those from ethnic minorities, who all tended to seek out information from lay sources. Some of the papers more closely explored how children and adolescents’ asthma is managed at school, with adolescents, carers and school staff all expressing a greater need for education, communication, and clearer processes. More concerningly, adolescents and their carers (particularly African Americans) reported that teachers sometimes did not believe the adolescents when they reported having asthma symptoms.

In relation to facilitators, education focusing on asthma self-management can improve asthma management and enhance recognition of symptoms, leading to reduced emergency department re-attendance. Interventions to improve education by using patient advocates, nurses and pharmacist educators have shown preliminary positive results in facilitating communication between healthcare professionals and patients, helping to obtain appointments for patients, providing social support to patients, and reinforcing self-management education. However, for acceptability it was important that the recipients felt that the education being offered was tailored to their needs. Needs were perceived by those with asthma to vary by age group, culture, language and ethnicity. Such education was reported to improve the use of action plans.

Information around how health beliefs influence self-management in patients with asthma are reported in Table 4. This theme was identified in 43 (77%) of the included papers. Beliefs about asthma can motivate very different behaviours. For example, some find poorly controlled asthma to be embarrassing, stigmatising and burdensome, so they try to conceal or normalise their symptoms or they may not take their medications or follow action plans. By contrast, others respond in a way that facilitates motivation to learn to live with their asthma, and fight back and gain control by taking their medications so they can engage with their everyday activities and prevent further attacks.

Barriers surrounding the sharing and transfer of responsibility between adults/carers and HCPs, as well as between children, their carers, and school staff with regards to asthma management also raise a range of different issues which, if not carefully addressed, can commonly result in confusion, disagreement and mismanagement. With regards to facilitators, nurses believe that involvement of children in consultations can facilitate self-management, as it provides an opportunity for children to show their parents they are becoming independent.

Feedback from healthcare professionals and patients regarding self-management interventions were reported in only 27 (48%) of the papers (see Table 5), but like the first theme, views in this theme were strongly expressed. Interventions included use of action plans, guidelines, internet and text message interventions to improve aspects of self-management; educational interventions in the form of a booklet or DVD; and medication reviews. Within this theme a greater balance of barriers and facilitators were expressed than for other themes. The main facilitator to asthma self-management was if healthcare professionals and patients regarded action plans and guidelines as useful. However, among those who seemed only marginally positive about action plan use, there seems to be an ‘ideal’ person for whom action plans were suitable, which often did not include themselves or their patients. Conversely, if generic action plans were used, or if healthcare professionals had negative views about action plans, the quality of their relationships with patients was reduced. Just as some healthcare professionals have reservations about guidelines and action plan use, preferring to rely on their own judgement about how to treat patients, some patients also felt this way about managing and modifying their own asthma care without consulting their healthcare professional.

Both healthcare professionals and patients/carers responded positively to the use of technology (mobile phone alarms, text messaging, emails, internet) to monitor and encourage self-management, provided they were familiar with using e.g., computers, mobile phones and systems did not take too long to access. These technological interventions were particularly valued by those with intellectual disabilities, adults and older adults, however, a lack of confidence with computers was one of the main barriers to using online self-management interventions for both patients and HCPs alike. Technology was also valued by patients, particularly young patients and those with poorly controlled asthma, to monitor their symptoms as part of an internet-based electronic action plan. Patients valued self-management education from a range of sources provided the style of writing was appropriate and comprehensible to lay people, and in their own language.

The last six themes are presented in Table 6. These themes occurred much less frequently than the first five themes. The presence of co-morbid physical conditions (discussed in 5 (9%) of included papers), can be a barrier to asthma self-management if the management of the different conditions conflict, and if asthma is not the patient’s top priority. However, healthy lifestyle behaviours (e.g., weight loss) were seen to facilitate benefit to multiple conditions at the same time.

Having a mood disorder or anxiety was reported in 10 (18%) papers. Carers and families often find managing the child’s asthma stressful, and may pass their worries on to the child. Many families experience stress around the transfer of responsibility from carer to child. Stressors or depression may also contribute to exacerbations or cause patients to neglect self-management.

The amount and type of social support patients have access to can act as facilitators or barriers to asthma management. Social support can have both positive influences (reported in 16 (29%) of papers), including friends and family members reminding those with asthma to take their medication, and by providing practical and emotional support. However, negative influences and barriers were also reported, within 13 (23%) of included papers, where friends or family members upset those with asthma by perceived over- and under-reactions to the condition such as disregarding severe symptoms, or giving opinions that conflict with GPs advice. This was particularly the case among ethnic minorities, and can lead to patients not complying with recommended treatment.

Patients with asthma use a variety of non-pharmacological methods in primarily three different ways to facilitate self-management. This theme was discussed within 12 (21%) of papers. In many cases methods such as drinking water, resting, or inhaling steam were used to try to relieve early asthma symptoms before taking reliever medication. Methods such as acupuncture or regularly opening windows were used in order to avoid the onset of asthma symptoms. Lifestyle changes (such as weight loss and exercise) were used with the aim of improving asthma control.

Issues involving access to healthcare (reported in 12 (21%) of the papers), can impact on the patient’s perceived ability to self-manage their asthma. Some patients have reported difficulties in accessing healthcare, including problems getting appointments in primary care, costs of healthcare, insurance and problems accessing medications. To facilitate access to healthcare and therefore self-management, patient advocates can help patients overcome access issues and asthma nurses can provide information about asthma management, particularly when GP appointments are not possible.

Finally, professional issues were reported in 7 (13%) of the papers. Only barriers were raised in this theme. Professional and organisational factors such as time restrictions during consultations, poor role definition and levels of teamwork and inter-professional communication, as well as practical issues such as access to testing, can act as barriers to implementing action plans and guidelines. Within schools, a lack of clarity regarding policies relating to asthma management, and poor communication between HCPs, school nurses, teachers and parents are also barriers to effective self-management.

Discussion

Main findings

This review aimed to identify individual patient, professional and organisational barriers and facilitators to asthma self-management, by examining qualitative evidence from the perspectives of patients, carers and healthcare professionals. Eleven themes were identified: partnership between the patient and their healthcare professional; issues around medications; education regarding asthma and its management; health beliefs; self-management interventions; co-morbid conditions; mood disorders and anxiety; social support; non-pharmacological methods; access to healthcare; and professional factors. Within the themes, barriers and facilitators at the level of patient, carer and healthcare professional were identified, which are summarised in Table 7.

Interpretation of findings in relation to previous research

Previous reviews have highlighted the importance of good communication between the healthcare professional and patient.19,20 The findings within our first theme, on partnership between patients and HCPs, were consistent with the findings of the previous reviews. Being able to listen to and respect patients was conducive to effective action plan use, and patients valued a healthcare professional who was sensitive and empathic. Patients and healthcare professionals also described aspects of asthma in different ways, and patients (particularly those with severe asthma) reported that information given by their healthcare professional should be easily understood. When patients view their treatment as effective, the patient/healthcare professional partnership is strengthened. One previous review19 suggested that the extent to which the patient was agreeable to advice and management strategies was determined by the ‘likeability’ of the provider. Our review adds that seeing the same GP across visits and receiving consistent advice also contributes to adherence.

Patient concerns regarding the safety of inhaled steroids and fears of dependence upon asthma medications have also been raised in previous reviews.19,20,76 Patients have reported that they experimentally adjust their medications and adapt the advice given by their healthcare professional, and reduce their dosage particularly when symptoms have reduced. Practical barriers to medication adherence, such as costs and the inconvenience of having to remember to take medications, have also been identified previously. In addition, our findings report the patient experience regarding dangers of such trial and error approaches to medication taking, and that patients use CAM in response to fears about more traditional asthma medicines. Our findings also suggest that the use of cues, technology based reminders, and routines may be facilitators, particularly for ethnic minorities and those with intellectual disabilities.

Patients have previously reported difficulty in recognising symptoms, not understanding what an asthma attack actually is, and having inadequate knowledge about asthma and its treatment.19,20 We concur with these findings and conclude that education is needed to help patients identify triggers. We also found that healthcare professionals perceive other barriers to asthma education, such as language barriers and poor understanding of medications, which may be more pronounced with ethnic minority patients. These concerns indicate changes are required to improve their engagement with the healthcare system.77

We found that when patients believe their asthma is serious, they are more likely to adhere to self-management strategies. However, perceived stigma regarding asthma leads to reduced adherence to medications, particularly in public. Similar findings have been reported regarding medication adherence and negative views of asthma.19,78 Our review also revealed that perceived negative views of asthma have led older people to conceal symptoms. These findings emphasise the importance of patient acceptance of asthma diagnosis and how this influences asthma management. This has been reported in relation to successful management in other conditions.79,80,81

Text message, Internet, booklet, DVD, and pharmacist interventions were perceived as acceptable self-management programmes. When consulted, patients report ways to improve interventions, which in turn might lead to improved self-management adherence. However, findings regarding action plan and guideline use are consistent with evidence that both healthcare professionals and patients hold negative views regarding the usefulness and practicality of action plans and guidelines, believing they are useful only for some people.20 Incompatibilities between reviews were identified regarding action plans, because the action plans were carried out on different patient populations. An Asthma UK report on barriers to effective emergency asthma care also recommended promoting awareness of guidelines by “signposting” patients to charities and discusses internal (negative beliefs regarding the suitability and evidence base of guidelines) and external (financial incentives or penalties) motivators of guideline use.82 The latter refers to the commissioning for quality and innovation framework (CQUIN) in the UK, where a proportion of healthcare providers’ income was linked to achieving good, quality practice.

Issues not raised in previous reviews were patient reported mood and anxiety problems that can impair self-management, and having a comorbidity perceived by patients as more important to treat.19,20,82 One previous review highlighted positive influences of social support,19 but we found it can also impact negatively on self-management outcomes, including over-and under-reactions to the condition by family members, and employer concerns regarding absenteeism due to asthma. Research in our review identified that the use of non-pharmacological methods to delay medication use appears to be contributing to poor control. Perceived access to healthcare is also raised in this review and highlights the use of patient advocates to assist with issues such as difficulty getting appointments.

Strengths and limitations of this review

This review includes mainly Caucasian patients with asthma, although some studies have explored the views of minority ethnic and other at risk groups. The majority of the issues uncovered still need to be explored further in these subgroups. Also, although we used a wide range of search terms, we may not have identified all published qualitative studies. Overall, the quality of the reviewed studies was high. However, future studies should provide sufficient information to enable assessment of whether the researchers have adequately considered the relationship between researcher and participants, and whether ethical issues have been considered.

Implications for future research, policy and practice

There are several areas that could impact on future research, policy and practice. With regard to practice, better adherence to asthma self-management may be achieved in a number of ways. First, evidence from our review suggested that educational interventions (including mobile phone and internet interventions) facilitated asthma self-management, and were perceived as acceptable and useful by HCPs and patients. Therefore, some patients, carers, teachers and healthcare professionals may benefit from further education. However, as some patients lack confidence with computers, their skills should be assessed prior to referral to ensure they receive appropriate interventions. With regard to research, future self-management intervention trials aiming to increase adherence to medications and action plans should include tailored education on recognising asthma symptoms, triggers, how to recognise an attack, patient concerns and beliefs regarding medications and non-pharmacological methods; and the importance and necessity of preventative medicine. Patients should also be advised to adjust medication only in collaboration with their GP, as a trial and error approach can cause symptoms to worsen.

The second area relates to the partnership that is built up between the healthcare professional and the patient/carer. A good relationship between the healthcare professional and the patient or carer facilitates asthma self-management. In practice, healthcare professionals should aim for continuity of care, so they are able to give consistent advice, be aware of the history, background (mental health and co-morbidities), and personal circumstances of the patient (such as social support networks). They should also try to understand the beliefs the patient and carer hold about asthma and their medications, as negative beliefs about medication may act as a barrier to effective self-management, and can be addressed if brought up in consultation.

Third, some GPs had negative views regarding the usefulness of guidelines and action plans, so did not always use them to conduct evidence-based practice. This is a modifiable barrier to asthma self-management. The use of proformas to ensure patients undergo care that follows current guidelines has been suggested,1 and we concur with Asthma UK’s recommendation of providing training to healthcare professionals to enhance feelings of competence in implementing guidelines.82

The fourth area is concerned with the professional and demographic features of the deliverer of the intervention. Evidence from this review suggests that nurses and AHPs are considered an effective source of information, so facilitate self-management. They could potentially be used instead of or in addition to doctors to deliver self-management interventions. Our review also provides evidence that pharmacist and patient advocate interventions facilitated asthma self-management.21,25 Future research could examine whether these or other healthcare professionals (such as physiotherapists) can deliver interventions to achieve outcomes as efficiently as nurses and doctors, and clarify the most effective team-based approach.

Fifth, cultural factors should be researched. Our findings indicated that some Latino, African American, and South Asian patients perceive access to healthcare as an issue, and have poor understanding of their medications. However, education in using action plans increased confidence in some of these populations. These findings suggest that ethnic minority patients may need more tailored education to facilitate understanding of their medications. Future qualitative research is required to explore how barriers to effective self-management might differ according to ethnic background, and whether separate interventions presented in the patients’ own language, and involving the family would benefit patients.

The sixth area for future investigation is the age of the person with asthma, as different factors might influence intervention success in older and younger populations. Only one study specifically explored older patients’ (≥50 years) beliefs regarding asthma. Wider research suggests older patients are at risk of being non-compliant in taking medications.83 Our findings suggest that this is the case for older patients with a longer-term diagnosis, who tend to have poorer asthma control. They may benefit from interventions focusing on education regarding acceptance of their condition and issues around medications. With regard to younger patients, this review suggests that in practice, involving children and adolescents in consultations, to show their carers how independent they are, could help facilitate the transfer of responsibility from the carer. As adolescents do not always take their asthma medications or attend asthma reviews, research could develop educational interventions (possibly technological) about the importance of this. As carers often have to educate schools in asthma management, further research could address ways to educate teachers and peers in asthma management, to reduce the social rejection felt by some adolescents, due to their teachers and peers disregarding their asthma symptoms.

Finally, future research could examine whether the following factors impact on the outcome of self-management interventions: patient comorbidities (which are often neglected in research on chronic disease), mood disturbances or anxiety, and the impact of the patient’s social support networks (which can act as a positive or negative influence on asthma self-management). The benefits and limitations of non-pharmacological methods to manage asthma could be further explored, and lastly, changes in practice could improve organisational barriers to asthma self-management, including time restrictions during consultations; support between healthcare professionals; unclear roles; poor teamwork; and practical issues such as lack of access to testing.

Conclusions

This review identified barriers and facilitators to asthma self-management that might explain, in part, why existing self-management interventions are not always effective. The beliefs and motivations of each patient need to be explored to uncover any potential barriers that will prevent successful self-management. Improvements to self-management might be achieved by educating patients and healthcare professionals to alter current beliefs about asthma management that oppose effective self-management, and improving patient/healthcare professional relationships via training healthcare professionals in effective communication skills. By exploring perspectives from adults, children and carers, and healthcare professionals regarding factors that hinder their use and recommendation of self-management advice, organisational and structural issues have also been highlighted which interact to prevent the implementation of self-management. These, along with viewpoints from particular subgroups can help us to refine interventions, improve adherence and ultimately achieve better outcomes for people with asthma.

Methods

Search strategy

We aimed to conduct a systematic, inclusive, reproducible and extensive search, since qualitative synthesis benefits from wide sampling of the literature.84 Our search was carried out for the period between January 1996 and March 2017. Five electronic databases were searched (Medline, EMBASE, AMED, CINAHL, and PsycINFO), and we checked the British Thoracic Society Guidelines.1 Search strategies were developed based on MeSH terms. The thesaurus term ‘asthma’ was combined with either ‘self-care’ or ‘self-management’, depending on the database searched. Identified studies were then limited to those that included variations of qualitative research in the title or abstract (qualitative, ethnography, ethnographic, grounded theory, constant comparative/ comparison, content analysis, or thematic). One reviewer (CM or SK) screened the titles and abstracts against inclusion criteria, and the full texts of all potentially relevant articles were obtained.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Included studies used qualitative data collection and analysis to identify perspectives of adults and children (and their carers) diagnosed with asthma, and the perspectives of healthcare professionals who were involved in providing interventions to improve self-management. Individuals with COPD were excluded. Non-English language studies, studies without any evaluative component, conference abstracts, PhD and Masters’ theses were excluded. Asthma self-management interventions were included if they used asthma education, self-monitoring, and/or the use of an asthma plan (digital or handwritten).

Quality appraisal

The Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) appraisal tool for qualitative research was used to assess study quality.85 The tool asks 10 questions to assess the validity, relevance and results of findings. In line with best practice,86 50% of papers were rated by two authors (CM or SK, and EAC). Minor discrepancies were discussed and resolved. Major discrepancies were resolved in discussion with one other author.

Data extraction and synthesis

The results and discussion sections of the included studies were read through by one of the reviewers (CM or SK), to extract the findings. Data were analysed using thematic synthesis, following the process described by Thomas and Harden87 to organise and summarise the findings from the multiple qualitative studies identified.84,88 Text labelled as ‘results’ or ‘findings’ in papers were considered as review findings. In some places findings were reported in discussion sections and were therefore also included. Data were entered into NVivo software for qualitative data analysis. Thematic synthesis took place in three stages. First, initial codes were generated using line-by-line coding (using a word or phrase to describe what was happening in each line) and organised using NVivo software.89 New codes were developed throughout initial coding. Before completing this stage, all coded text were examined to check they had been interpreted consistently. In the second stage, codes were collated and organised into descriptive themes. Finally, themes were revised and re-grouped into analytical themes (initial themes were combined, separated and discarded) by group discussion among the researchers. Barriers and facilitators were inferred from the views expressed by patients, carers, and healthcare professionals, and the implications of these views for policy and practice were considered.

References

BTS/SIGN. British Thoracic Society and Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. British guideline on the management of asthma: a national clinical guideline. http://www.sign.ac.uk/pdf/SIGN141.pdf (2014).

Adams, K., Greiner, A. C., Corrigan, J. M. & (eds.) The 1st Annual Crossing the Quality Chasm Summit: A Focus on Communities. 57 (National Academic Press, 2004).

Gillisen, A. Patient’s adherence in asthma. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 58(Suppl 5), 205–222 (2007).

Gibson Peter, G. et al. Self-management education and regular practitioner review for adults with asthma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003, https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD001117 (2002a).

Demoly, P., Annunziata, K., Gubba, E. & Adamek, L. Repeated cross-sectional survey of patient-reported asthma control in Europe in the past 5 years. Eur. Respir. Rev. 21, 66–74 (2012).

Rabe, K. F., Vermeire, P. A., Soriano, J. B. & Maier, W. C. Clinical management of asthma in 1999: the asthma insights and reality in Europe (AIRE) study. Eur. Respir. J. 16, 802–807 (2000).

Newman, S., Steed, L. & Mulligan, K. Self-management interventions for chronic illness. Lancet 364, 1523–1537, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17277-2 (2004).

Roy, A. et al. Asthma self management education with either regular healthcare professional review or written action plans or both in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD009479 (2011).

Dean, S., Young, V., Elley, R. & Bruton, A. Patient and clinician perceptions of asthma education and management in resistant asthma: a qualitative study. N.Z. Fam. Physician 35, 257–262 (2008).

Glasgow, R., Vogt, T. & Boles, S. Evaluating the public health impact of health promotion interventions: The RE-AIM framework. Am. J. Public Health 89, 1322–1327 (1999).

Jones, A., Pill, R. & Adams, S. Qualitative study of views of health professionals and patients on guided self management plans for asthma. BMJ 321, 1507–1510 (2000).

Pinnock, H. et al. Implementing supported self-management for asthma: a systematic review and suggested hierarchy of evidence of implementation studies. BMC Med. 13, 127–127 (2015).

Toelle, B. & Ram, F. S. Written individualised management plans for asthma in children and adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, CD002171, https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD002171.pub3 (2011).

Bravata, D. et al. Quality improvement strategies for children with asthma a systematic review. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 163, 572–581 (2009).

Haby, M. M., Waters, E., Robertson, C. F., Gibson, P. G. & Ducharme, F. M. Interventions for educating children who have attended the emergency room for asthma. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. CD001290, https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD001290 (2001).

Wolf, F., Guevara James, P., Grum Cyril, M., Clark Noreen, M. & Cates Christopher, J. Educational interventions for asthma in children. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD000326 (2002).

Gibson, P. G. et al. Self-management education and regular practitioner review for adults with asthma. Cochrane. Database Syst. Rev. CD001117 https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD001117 (2003).

Guevara, J. P., Wolf, F. M., Grum, C. M. & Clark, N. M. Effects of educational interventions for self management of asthma in children and adolescents: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 326, 1308–1309 (2003).

Bender, B. G. & Bender, S. E. Patient-identified barriers to asthma treatment adherence: responses to interviews, focus groups, and questionnaires. Immunol. Allergy Clin. North Am. 25, 107–130 (2005).

Ring, N. et al. Understanding what helps or hinders asthma action plan use: a systematic review and synthesis of the qualitative literature. Patient Educ. Couns. 85, e131–e143 (2011).

Black, H. L. et al. An analysis of contextual information relevant to medical care unexpectedly volunteered to researchers by asthma patients. J. Asthma 49, 731–737 (2012).

Clark, N. M. & Nothwehr, F. Self-management of asthma by adult patients. Patient Educ. Couns. 32, S5–S20 (1997).

George, M., Campbell, J. & Rand, C. Self-management of acute asthma among low-income urban adults. J. Asthma 46, 618–624 (2009).

Newcomb, P. A., McGrath, K. W., Covington, J. K., Lazarus, S. C. & Janson, S. L. Barriers to patient-clinician collaboration in asthma management: the patient experience. J. Asthma 47, 192–197 (2010).

Young, H. N. et al. Patient and phaRmacist telephonic encounters (PARTE) in an underserved rural patient population with asthma: results of a pilot study. Telemed. J. E. Health 18, 427–433 (2012).

Pradel, F. G., Hartzema, A. G. & Bush, P. J. Asthma self-management: the perspective of children. Patient Educ. Couns. 45, 199–209 (2001).

Knight, D. Beliefs and self-care practices of adolescents with asthma. Issues Compr. Pediatr. Nurs. 28, 71–81 (2005).

Martin, M., Beebe, J., Lopez, L. & Faux, S. A qualitative exploration of asthma self-management beliefs and practices in Puerto Rican families. J. Health Care Poor Underserved 21, 464–474 (2010).

Peterson-Sweeney, K., McMullen, A., Yoos, H. L. & Kitzman, H. Parental perceptions of their child’s asthma: management and medication use. J. Pediatr. Health Care 17, 118–125 (2003).

Arcoleo, K., Zayas, L. E., Hawthorne, A. & Begay, R. Illness representations and cultural practices play a role in patient-centered care in childhood asthma: experiences of Mexican mothers. J. Asthma 52, 699–706 (2015).

Egginton, J. S. et al. Enhancing school asthma action plans: qualitative results from southeast Minnesota beacon stakeholder groups. J. Sch. Health 83, 885–895 (2013).

George, M. et al. Changes in clinical conversations when providers are informed of asthma patients’ beliefs about medication use and integrative medical therapies. Heart Lung 45, 70–78 (2016).

Gibson-Scipio, W., Gourdin, D. & Krouse, H. J. Asthma Self-Management Goals, Beliefs and Behaviors of Urban African American Adolescents Prior to Transitioning to Adult Health Care. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 30, e53–e61 (2015). 51p.

Gibson-Scipio, W. & Krouse, H. J. Goals, beliefs, and concerns of urban caregivers of middle and older adolescents with asthma. J. Asthma 50, 242–249 (2013).

Janevic, M. R., Ellis, K. R., Sanders, G. M., Nelson, B. W. & Clark, N. M. Self-management of multiple chronic conditions among African American women with asthma: a qualitative study. J. Asthma 51, 243–252 (2014).

Mammen, J. R., Rhee, H., Norton, S. A. & Butz, A. M. Perceptions and experiences underlying self-management and reporting of symptoms in teens with asthma. J. Asthma 54, 143–152 (2017).

McClelland, M., Wenz, C., Sood, K. & Yono, A. Perceptions of pediatric asthma in African American underserved families using metaphorical analysis. J. Spec. Pediatr. Nurs. 18, 312p (2013).

Melton, C., Graff, C., Holmes, G. N., Brown, L. & Bailey, J. Health literacy and asthma management among African-American adults: an interpretative phenomenological analysis. J. Asthma 51, 703–713 (2014).

Mowrer, J. L. et al. Patients’ and providers’ perceptions of asthma and asthma care: a qualitative study. J. Asthma 52, 949–956 (2015).

O’Conor, R. et al. A qualitative investigation of the impact of asthma and self-management strategies among older adults. J. Asthma 54, 39–45 (2017).

Pai, S. et al. “Looking out for each other”: a qualitative study on the role of social network interactions in asthma management among adult Latino patients presenting to an emergency department. J. Asthma 51, 714–719 (2014).

Quaranta, J., Wool, M., Logvis, K., Brown, K. & Joshy, D. Interpersonal influences on the asthma self-management skills of the rural adolescent. Online J. Rural Nurs. Health Care 14, 126p (2014).

Speck, A. L., Nelson, B., Jefferson, S. O. & Baptist, A. P. Young, African American adults with asthma: what matters to them? Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 112, 35–39 (2014). 35p.

Griffiths, C. et al. Influences on hospital admission for asthma in south Asian and white adults: qualitative interview study. BMJ 323, 962–966 (2001).

Hussein, S. & Partridge, M. Perceptions of asthma in South Asians and their views on educational materials and self-management plans: a qualitative study. Patient Educ. Couns. 48, 189–194 (2002).

Moffat, M., Cleland, J., van der Molen, T. & Price, D. Poor communication may impair optimal asthma care: a qualitative study. Fam. Pract. 24, 65–70 (2007).

Pinnock, H., Slack, R., Pagliari, C., Price, D. & Sheikh, A. Understanding the potential role of mobile phone-based monitoring on asthma self-management: qualitative study. Clin. Exp. Allergy 37, 794–802 (2007).

Shaw, A., Thompson, E. A. & Sharp, D. Complementary therapy use by patients and parents of children with asthma and the implications for NHS care: a qualitative study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 6, 76 (2006).

Steven, K., Morrison, J. & Drummond, N. Lay versus professional motivation for asthma treatment: a cross-sectional, qualitative study in a single Glasgow general practice. Fam. Pract. 19, 172–177 (2002).

Walsh, S., Hagan, T. & Gamsu, D. Rescuer and rescued: applying a cognitive analytic perspective to explore the ‘mis-management’ of asthma. Br. J. Med. Psychol. 73, 151–168 (2000).

Callery, P., Milnes, L., Verduyn, C. & Couriel, J. Qualitative study of young people’s and parents’ beliefs about childhood asthma. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 53, 185–190 (2003).

Callery, P. & Milnes, L. Communication between nurses, children and their parents in asthma review consultations. J. Clin. Nurs. 21, 1641–1650 (2012).

Meah, A., Callery, P., Milnes, L. & Rogers, S. Thinking ‘taller’: sharing responsibility in the everyday lives of children with asthma. J. Clin. Nurs. 19, 1952–1959 (2010).

Normansell, R. & Welsh, E. “Asthma can take over your life but having the right support makes that easier to deal with.” Informing research priorities by exploring the barriers and facilitators to asthma control: A qualitative analysis of survey data. Asthma Res Pract 1, https://doi.org/10.1186/s40733-015-0011-5 (2015).

Douglass, J. et al. A qualitative study of action plans for asthma. BMJ 324, 1003–1005 (2002).

Goeman, D. P. et al. Back for more: a qualitative study of emergency department reattendance for asthma. Med. J. Aust. 180, 113–117 (2004).

Goeman, D. P., O’Hehir, R. E., Jenkins, C., Scharf, S. L. & Douglass, J. A. ‘You have to learn to live with it’: a qualitative and quantitative study of older people with asthma. Clin. Respir. J. 1, 99–105 (2007).

Saini, B. et al. Asthma disease management-Australian pharmacists’ interventions improve patients’ asthma knowledge and this is sustained. Patient Educ. Couns. 83, 295–302 (2011).

Andrews, K. L., Jones, S. C. & Mullan, J. Perceptions and practices of adults with Asthma: A social cognitive analysis. J. Asthma Allergy Educ. 4, 49–56 (2013).

Davis, S. R. et al. Knowledge that people with intellectual disabilities have of their inhaled asthma medications: messages for pharmacists. Int. J. Clin. Pharm. 38, 135–143 (2016).

Ross, C. J., Williams, B. A., Low, G. & Vethanayagam, D. Perceptions about self-management among people with severe asthma. J. Asthma 47, 330–336 (2010).

Pelaez, S. et al. Patients’ perspective of barriers and facilitators to taking long-term controller medication for asthma: A novel taxonomy. BMC Pulm. Med. 25, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12890-015-0044-9 (2015).

Peláez, S., Bacon, S. L., Lacoste, G. & Lavoie, K. L. How can adherence to asthma medication be enhanced? Triangulation of key asthma stakeholders’ perspectives. J. Asthma 53, 1076–1084 (2016).

Cheng, S., Chen, Y., Liou, Y. M., Wang, K. K. & Mu, P. Mothers’ experience with 1st–3rd-grade children with asthma assisting their child’s adaptation of school life in Taiwan. J. Clin. Nurs. 19, 1960–1968 (2010).

Chiang, L. C., Huang, J. L. & Chao, S. Y. A comparison, by quantitative and qualitative methods, between the self-management behaviors of parents with asthmatic children in two hospitals. J. Nurs. Res. 13, 85–96 (2005).

Jan, R. H., Sophie Lee, H. T. & Cheng, S. C. Parents’ views of self-management for children with moderate to severe persistent asthma. Tzu. Chi. Med. J. 26, 34–39 (2014).

Anhoj, J. & Moldrup, C. Feasibility of collecting diary data from asthma patients through mobile phones and SMS (short message service): response rate analysis and focus group evaluation from a pilot study. J. Med. Internet Res. 6, e42 (2004).

Anhoj, J. & Nielsen, L. Quantitative and qualitative usage data of an Internet-based asthma monitoring tool. J. Med. Internet Res. 6, e23 (2004).

Tan, N. C., Tay, I. H., Ngoh, A. & Tan, M. A qualitative study of factors influencing family physicians’ prescription of the written asthma action plan in primary care in Singapore. Singapore Med. J. 50, 160–164 (2009).

Tan, N. C., Soo, W. F. & Ngoh, A. S. A qualitative study of parental use of the written asthma action plan for their children in primary care in Singapore. J Asthma Allergy Educ 2, 185–188 (2011).

Van Der Meer, V. et al. Internet-based self-management offers an opportunity to achieve better asthma control in adolescent. Chest 132, 112–119, https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.06-2787 (2007).

Klok, T., Lubbers, S., Kaptein, A. A. & Brand, P. L. Every parent tells a story: Why non-adherence may persist in children receiving guideline-based comprehensive asthma care. J. Asthma 51, 106–112 (2014).

Lingner, H. et al. What patients really think about asthma guidelines: Barriers to guideline implementation from the patients’ perspective. BMC Pulm. Med. 17, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12890-016-0346-6 (2017).

Buetow, S. et al. GP care for moderate to severe asthma in chilren: What do infrequently attending mothers disagree with and why? Fam. Pract. 20, 155–161 (2003).

Santati, S., Ratinhorn, A. & Christian, B. Parents’ experiences in asthma attack prevention: struggling to take control. Thai. J. Nurs. Res. 7, 186–198 (2003).

Pound, P. et al. Resisting medicines: a synthesis of qualitative studies of medicine taking. Soc. Sci. Med. 61, 133–155, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.11.063 (2005).

Shaw, S. J., Huebner, C., Armin, J., Orzech, K. & Vivian, J. The role of culture in health literacy and chronic disease screening and management. J. Immigr. Minor Health 11, 460–467 (2009).

Kolbe, J., Fergusson, W., Vamos, M. & Garrett, J. Case-control study of severe life threatening asthma (SLTA) in adults: psychological factors. Thorax 57, 317–322 (2002).

Anthony, H., Valinsky, L., Inbar, Z., Gabriel, C. & Varda, S. Perceptions of hypertension treatment among patients with and without diabetes. BMC Fam. Pract. 13, 24 (2012).

Hesser, H., Westin, V. Z. & Andersson, G. Acceptance as a mediator in internet-delivered acceptance and commitment therapy and cognitive behavior therapy for tinnitus. J. Behav. Med. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-013-9525-6 (2013).

Gregg, J. A., Callaghan, G. M., Hayes, S. C. & Glenn-Lawson, J. L. Improving diabetes self-management through acceptance, mindfulness, and values: a randomized controlled trial. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 75, 336–343 (2007).

ASTHMA UK. Barriers to effective emergency asthma care. http://www.asthma.org.uk/ (2014).

Ryan, A. A. Medication compliance and older people: a review of the literature. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 36, 153–162 (1999).

Joffe, H. & Yardley, L. in Research Methods for Clinical and Health Psychology. (eds Marks D. F. & Yardley L.) 56–68 (Sage, 2004).

Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. CASP Qualitative Research Checklist. http://www.casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists (2017).

Schlosser, R. W. Appraising the quality of systematic reviews. Focus Technical Brief 17 (2007).

Thomas, J. & Harden, A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 8, 45 (2008).

Boyatzis, R. E. Transforming Qualitative Information: Thematic and Code Development. (Sage Publications, 1998).

NVivo. NVivo qualitative data analysis software; QSR International Pty Ltd. Version 10, 2012. (2012).

Acknowledgements

This research was made possible by an Asthma UK Priority Needs grant, ref AUK-PG-2012-180, awarded to Sarah Kirby (PI), Mike Thomas, Anne Bruton, Lucy Yardley and Matthew Hankins.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.M.—Conducted the review (data collection and analysis) wrote the first draft, commented on drafts. E.A.-C.—day-to-day conduct of the review, revised the paper, commented on drafts. S.K.—Conception of the review and day-to-day conduct of the review, commented on drafts, updated the review, revised the paper. M.T.—conception of the review, commented on drafts. A.B.—conception of the review, commented on drafts. L.Y.—conception of the review, commented on drafts. M.H.—conception of the review, commented on drafts. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing financial interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Miles, C., Arden-Close, E., Thomas, M. et al. Barriers and facilitators of effective self-management in asthma: systematic review and thematic synthesis of patient and healthcare professional views. npj Prim Care Resp Med 27, 57 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41533-017-0056-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41533-017-0056-4

This article is cited by

-

Common barriers and enablers to the use of non-drug interventions for managing common chronic conditions in primary care: an overview of reviews

BMC Primary Care (2024)

-

Assessing the interrelationship between asthma and obesity self-management behaviors

Journal of Behavioral Medicine (2024)

-

Factors perceived by health professionals to be barriers or facilitators to caries prevention in children: a systematic review

BMC Oral Health (2023)

-

Engaging Ethnically Diverse Populations in Self-Management Interventions for Chronic Respiratory Diseases: A Narrative Review

Pulmonary Therapy (2023)

-

Understanding the journeys of patients with an asthma exacerbation requiring urgent therapy at a primary care clinic

BMC Pulmonary Medicine (2022)