Key Points

-

Allergic diseases, including asthma, rhinitis, conjunctivitis and food allergies, have reached epidemic proportions worldwide. Allergic inflammatory responses are mediated by expansion of the T helper 2 (TH2)-cell subset of T cells together with isotype switching of B cells to generate IgE antibodies specific for common environmental allergens.

-

A comprehension of the cellular and soluble mediator components of allergic inflammatory responses is important for understanding the mechanisms of current treatment modalities and in leading to the identification of new therapeutic targets.

-

In theory, allergen avoidance should be beneficial as a primary or secondary prophylaxis, but most studies show discrepancies. Inhaled corticosteroids, and short- and long-acting β2-adrenoceptor agonists (SABAs and LABAs) are now the mainstay of asthma treatment, having established anti-inflammatory and bronchodilator effects. Immunomodulators are an option for those patients whose symptoms are not controlled by conventional treatments, although cytokine-directed therapies offer new promise.

-

Allergen immunotherapy is known to induce immunological tolerance and has been recommended for the management of allergic diseases. Allergen extracts or recombinant allergens can be administered either by regular subcutaneous injections or sublingually, and these are the only treatments that influence the natural history of allergic disease.

-

IgE and mast cells are cogent therapeutic targets. A humanized, non-anaphylactic, IgE-specific IgG1 antibody has been developed recently and is effective for the treatment of severe allergic asthma and allergic rhinoconjunctivitis. Several therapies that inhibit FcɛRI-mediated activation of mast cells have been identified and are now in clinical development.

-

Allergic inflammation has been characterized as being mainly a TH2-cell-mediated disease; therefore, efforts to alter the balance between TH2 cells, TH1 cells and regulatory T (TReg) cells in asthma have been aggressively pursued, either by inhibiting TH2-cell cytokines — in particular, interleukin-4 (IL-4), IL-13 and IL-5 — or by promoting TH1-cell and TReg-cell responses. Given that tissue injury and aberrant repair are also important components of chronic allergic diseases, restoration of the barrier function by administration of growth factors is another promising therapeutic strategy.

Abstract

Allergic diseases have reached epidemic proportions worldwide. An understanding of the cellular and soluble mediators that are involved in allergic inflammatory responses not only helps in understanding the mechanisms of current treatments, but is also important for the identification of new targets that are amenable to both small-molecule and biological interventions. There is now considerable optimism with regards to tackling the allergy epidemic in light of improvements in systemic and mucosal allergen-specific immunotherapy, the identification of key cytokines and their receptors that drive T-helper-2-cell polarization, a clearer understanding of the pathways of leukocyte recruitment and the signalling pathways that are involved in cell activation and mediator secretion, and new approaches to vaccine development.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Allergic diseases are those that are mediated by the expansion of the T helper 2 cell (TH2-cell) subset of T cells, together with isotype switching of B cells to generate IgE antibodies specific for common environmental allergens1. Although almost half of the urban population worldwide is atopic (genetically predisposed to produce IgE antibodies in serum) and most allergy sufferers are atopic, it is possible to develop allergies in the absence of atopy — common examples of this are wasp and bee allergies. Allergic reactions are symptomatic responses to a normally innocuous environmental antigen. Allergic diseases are highly patient specific and include asthma, rhinoconjunctivitis, sinusitis, food allergy, atopic dermatitis, angioedema and urticaria, anaphylaxis, and insect and drug allergy, all of which can occur either alone or in combination. Allergic diseases have reached epidemic proportions worldwide and their incidence is continuing to increase in association with the Western lifestyle, making it imperative that we continue to improve our understanding of the mechanisms of allergic disease2. Allergies can affect all age groups and can appear at any time, but it is the marked increase of allergies in children and young adults that is of particular concern3. It is probable that environmental exposure to potential allergens early in life or during pregnancy has a pivotal role in the development of allergy and its expression in different organs (Box 1).

Since the first description of 'reagin' in 1922 and its characterization as IgE in 1966 (Ref. 4), considerable advances have been made in understanding the immunological pathways that lead to allergy, the chemical mediators involved and the innate and adaptive immune responses that regulate its expression. Progress has also occurred in understanding the structural and intrinsic biology of environmental agents that determine their allergenicity, and the role of other environmental factors, such as pollutants and microorganisms, in augmenting or inhibiting allergen sensitization5. As most allergic disorders express themselves clinically at epidermal or mucosal surfaces, a breakdown of the physical barrier that is normally provided by these surfaces and altered innate immunity is also recognized to be of great importance in allergic reactions. The study of interactions between many susceptibility genes and the environment is revealing new pathophysiological mechanisms and creating unique opportunities for the prevention and treatment of allergy.

The time has arrived to take a fresh look at the new treatment strategies that are now appearing on the horizon. This Review provides an overview of possible innovative therapeutics, focusing on some exciting new immunological and molecular targets and on vaccine approaches for allergy and asthma.

The allergic cascade

The allergic inflammatory response is characterized by selection of the TH2-cell pathway, which is initiated by the uptake of allergens by professional antigen-presenting cells (APCs) that present selected peptides on MHC class II molecules to naive T cells, thereby directing them in favour of a TH2-cell phenotype in which the transcription factor GATA3 (GATA-binding protein 3) mediates cytokine secretion6 (Fig. 1). This is in contrast to the TH1-cell phenotype that is dominant in autoimmune diseases, in which T-bet controls cytokine secretion — for example, the secretion of interferon-γ (IFNγ)7. The crucial role played by dendritic cells (DCs) acting as professional APCs in this sensitization process is reviewed by Hamida Hammad and Bart Lambrecht in this issue8. B cells are also important for allergen capture and processing, especially in the presence of small amounts of allergen9.

In predisposed individuals, initial exposure(s) of professional antigen-presenting cells (APCs) to allergen leads mainly to the activation of allergen-specific T helper 2 (TH2) cells and IgE synthesis, which is known as allergic sensitization. Subsequent exposures to allergen cause inflammatory-cell recruitment and activation and mediator release, which are responsible for early (acute) allergic responses and late allergic responses. In the early allergic response, within minutes of contact with allergen, IgE-sensitized mast cells degranulate, releasing both pre-formed and newly synthesized mediators in sensitized individuals. These include histamine, cysteinyl leukotrienes and cytokines, which promote vascular permeability, smooth-muscle contraction and mucus production. Chemokines released by mast cells and other cell types direct the recruitment of inflammatory cells that contribute to the late allergic response, which is characterized by an influx of eosinophils and TH2 cells. Eosinophils release a large number of pro-inflammatory mediators, including cysteinyl leukotrienes and basic proteins (cationic proteins, eosinophil peroxidase, major basic protein and eosinophil-derived neurotoxin), and they might be an important source of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-3 (IL-3), IL-5 and IL-13. There is now evidence that TH1-cell responses might also be responsible for some of the pathogenic features in patients suffering from chronic forms of atopy, including epithelial apoptosis and smooth-muscle-cell activation. Regulatory T (TReg) cells are another important subset of CD4+ T cells with implications for the suppression of TH2-cell responses in humans involving the inhibitory cytokines IL-10 and transforming growth factor-β (TGFβ). Another newly identified CD4+ T-cell subset, known as TH17 cells on the basis of secretion of IL-17A and IL-17F, seems to be specifically associated with the neutrophilic inflammatory events that occur during disease exacerbation and in tissue remodelling. FceRI, high-affinity receptor for IgE; IFNγ, interferon-γ; TCR, T-cell receptor; TNF, tumour-necrosis factor.

In the presence of co-stimulation, T cells coordinately upregulate expression of a cluster of genes encoded on human chromosome 5q31–33 that include the genes encoding interleukin-3 (IL-3), IL-4, IL-5, IL-9, IL-13 and granulocyte/macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF)10. These cytokines are involved in the class-switching of B cells to IgE synthesis (IL-4 and IL-13), the recruitment of mast cells (IL-4, IL-9 and IL-13) and the maturation of eosinophils (IL-3, IL-5 and GM-CSF) and basophils (IL-3 and IL-4), which are the main mediator-secreting effector cells of the allergic response. The imbalance between TH2-cell and TH1-cell (that is, IFNγ-producing) responses has formed the basis for our understanding of allergic immune responses for more than two decades11. More recently, regulatory T cells (TReg cells) have been discovered as another pivotal subset of CD4+ T cells with implications for allergic disease. These cells are characterized by expression of the transcription factor FOXP3 (Forkhead box P3) and the IL-2 receptor (CD25)12, but in contrast to activated effector T cells, they express low levels of CD127 (Ref. 13). Extensive studies in mouse models strongly implicate TReg cells in the suppression of allergic responses14, and there is emerging evidence that TReg cells also control TH2-cell responses in humans through the inhibitory cytokines IL-10 and transforming growth factor-β (TGFβ), with atopy resulting from an imbalance between TH2 cells and TReg cells15.

Another newly identified type of CD4+ T cell has been named the TH17 cell on the basis of secretion of IL-17A and IL-17F, which are associated with neutrophilic inflammation16. The transcription factor RORγt (retinoic-acid-receptor-related orphan receptor-γt) identifies TH17 cells and is selectively activated by IL-1β and IL-6 (Ref. 17), with IL-23 being responsible for the proliferation of these cells. IL-17A is overexpressed in asthmatic airways in association with neutrophil influx18 and it induces production of the neutrophil chemoattractant IL-8 (CXCL8) by human airway smooth muscle cells19.

Once an individual is sensitized to a particular allergen, subsequent encounters with that allergen cause crosslinking of IgE bound to the high-affinity IgE receptor (FcɛRI) to stimulate the release of granule-associated and newly generated mediators that are responsible for the early allergic response (which occurs within 1–30 minutes), together with the release of cytokines and chemokines that recruit macrophages, eosinophils and basophils that comprise the late response (within 6–72 hours)20. Autacoid mediators such as histamine and the cysteinyl leukotrienes (CysLTs) increase endothelial expression of P-selectin and E-selectin to initiate leukocyte rolling, followed by the expression of intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM1) and vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 (VCAM1), which interact with integrin receptors to arrest the leukocyte and assist its passage into the perivascular space21. Chemokines, such as CC-chemokine ligand 2 (CCL2), CCL8, CCL7 and CCL13 (monocyte chemotactic proteins 1–4), CCL3, CCL24 and CCL26 (eotaxins 1–3) and CCL5 (RANTES), direct and prime leukocytes for mediator secretion22. Although adhesion molecules and chemokines might seem to be attractive therapeutic targets at which to direct inhibitors, none has yet been translated into clinical use23. The epithelium has a particularly important role in mucosal and skin allergy as the source of crucial cytokines and chemokines — such as CCL17 (TARC), CCL22 (MDC), IL-25 (IL-17E) and IL-33 — that promote TH2-cell function, as well as thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP), which interacts with DCs and mast cells to increase the TH2-cell response24,25.

In asthma and atopic dermatitis, the epithelium is more susceptible to oxidant stress and injury26. In asthma, the presence of IL-13, as well as epidermal, neural, vascular and fibroblast growth factors, leads to mucous metaplasia and remodelling of the airway walls27 (Fig. 2). However, it is still not known how these inflammatory and remodelling events relate to the increase in airway smooth muscle and its increased responsiveness in asthma. In the case of atopic dermatitis, TH1-cell pathways are also important through the release of IFNγ, which induces keratinocyte apoptosis and the recruitment of further T cells into the lesion28.

The airways in asthma show characteristics of a chronic wound with evidence of ongoing epithelial injury and repair. As in any wound, responses to tissue injury create the necessary stimuli to recruit the underlying mesenchyme to participate in the repair process through the release of various growth factors and cytokines. Interleukin-13 (IL-13) is a key cytokine in this process, driving goblet-cell metaplasia and myofibroblast differentiation, and supporting immunoglobulin class-switching to IgE. Both in human asthma and in mouse models of allergen-induced remodelling, epidermal growth factors (EGFs), transforming growth factor-β (TGFβ), fibroblast growth factor 2 (FGF2) and FGF7 (KGF), insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF1), platelet-derived growth factor AA (PDGFAA) and PDGFBB, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and IL-5 are all implicated. The epithelium is more susceptible to oxidant stress and to injury by prematurely entering into apoptosis. Impaired wound repair leads to the increased production of growth factors by damaged epithelium, activated structural cells and infiltrating inflammatory cells. In asthma this leads to myofibroblast activation, mesenchymal hyperplasia, mucous metaplasia and the induction of structural changes throughout the airway wall. The ongoing eosinophil- and mast-cell-driven inflammatory responses are responsible for the maintenance and progression of tissue injury and repair. The activation of T helper 1 (TH1)-cell pathways is also important for tissue inflammation and remodelling through the release of interferon-γ (IFNγ, which induces epithelial apoptosis and the recruitment of further T cells into the lesion) and tumour-necrosis factor (TNF, which elicits the proliferation and activation of myofibroblasts and fibroblasts and induces a hypercontractile phenotype in airway smooth muscle cells). APC, antigen-presenting cell; GM-CSF, granulocyte/macrophage colony-stimulating factor.

Allergen avoidance

In atopic individuals, allergen sensitization is fundamental to the development of any allergic disease. Therefore, avoidance of allergens before or after sensitization should be beneficial as primary or secondary prophylaxis. In the case of house dust mites, birth-cohort studies have shown that the level of allergen exposure early in life correlates with the extent of sensitization29. For domestic pets, the situation is more complex, with early-life exposure decreasing rather than increasing allergen sensitization, possibly as a result of simultaneous exposure to inhibitory products from non-pathogenic microorganisms, whereas exposure later in childhood leads to sensitization. Trials looking at the effects of decreased exposure to house dust mites in early childhood have produced mixed results, with most of the trials either showing no effect30 or increased IgE sensitization31. This disappointing response to primary prophylaxis can be explained by the fact that extremely low allergen exposures can lead to sensitization and, as a result, anything less than complete allergen avoidance is unlikely to be successful. Greater success has been obtained by using multiple early-life interventions in addition to the avoidance of house dust mites and pets, such as breast-feeding with the mother on a low-allergen diet or giving extensively hydrolysed formula milk to babies32. A similar situation applies to peanut allergy, in which avoidance during pregnancy and early infancy can increase rather than protect against sensitization33. Therefore, exposure to a high dose of peanut, rather than avoidance in infancy, might be a way to induce protective tolerance34.

In children who are already sensitized, single or combination interventions to decrease exposure to both dietary and aeroallergens result in a meaningful and sustained improvement in the control of asthma and rhinitis. However, in adults, the data are far less convincing, probably because of the many allergenic and non-allergenic factors that contribute to ongoing disease. In the case of asthma and rhinitis, a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study of allergen-impermeable bed covers involving 1,122 adults with asthma and 279 patients with allergic rhinitis failed to show any beneficial effects of reducing exposure to house dust mites35,36.

Established treatments

Inhaled corticosteroids and short- and long-acting β2-adrenoceptor agonists (SABAs and LABAs) are now the mainstay of asthma treatment as advocated by disease-management guidelines. In the case of rhinitis, α-adrenoceptor agonists are used to relieve nasal congestion, and non-sedating H1-antihistamines and topical corticosteroids are well-established control therapies. So, for most allergic disorders, a combination of symptom-relieving and control therapies forms the basis of management guidelines. Asthma provides a particularly good example of how an understanding of the pathophysiology of the disease has underpinned the treatment approaches that are in use.

Corticosteroids. TH2-cell-mediated inflammation in asthmatic airways is suppressed by corticosteroids through the inhibition of expression of cytokines, chemokines and adhesion molecules37, whose encoding genes are regulated by transcription factors such as nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) and activator protein 1 (AP1)38. Free corticosteroids diffuse across the cell membrane, where they interact with cytoplasmic glucocorticoid receptors. This results in the activation of these receptors and their subsequent translocation to the nucleus, where the transcriptional activity of target genes is modulated by several different mechanisms, including gene transactivation and gene transrepression39 (Fig. 3).

Corticosteroids enter the cell, bind to the glucocorticoid receptor (GR) in the cytoplasm and translocate to the nucleus, where the transcription of target genes is initiated. Many genes contain glucocorticosteroid response elements (GREs) in their promoters. Through transactivation, binding of the activated glucocorticoid receptor homodimer to a GRE in the promoter region of steroid-sensitive genes leads to the transcription of genes encoding anti-inflammatory mediators such as annexin-1 (lipocortin-1), secretory leukoprotease inhibitor (SLPI), interleukin-10 (IL-10) and the inhibitor of nuclear factor-κB (IκBα). Through transrepression, the glucocorticoid receptor–corticosteroid complex interacts with large co-activator molecules with intrinsic histone acetyltransferase (HAT) activity (such as cyclic AMP response element binding protein, CBP), which are activated by pro-inflammatory transcription factors (such as NF-κB and AP1), thus switching off expression of the inflammatory genes that are activated by these transcription factors. RNA pol II, RNA polymerase II.

Whereas inhaled corticosteroids are highly effective at suppressing airway inflammation, they do not influence the natural history of the disease, even when treatment is started early in childhood40,41. Inhaled corticosteroids are largely ineffective in virus-induced exacerbations42 and in those asthmatics who smoke43.

β2-adrenoceptor agonists. Inhaled SABAs such as salbutamol and turbutaline are the most effective bronchodilators currently available for the rapid relief of asthma symptoms. After binding of these agonists to the β2-adrenoceptor, adenylate cyclase is stimulated by the signal-transducing Gs protein to increase production of cyclic adenosine 3′5′-monophosphate (cAMP), thereby activating protein kinase A. This mediates smooth-muscle relaxation through the phosphorylation of myosin light-chain kinase and by opening Ca2+-dependent K+ (KCa) channels, which relieves bronchoconstriction in asthma.

The two inhaled LABAs, formoterol and salmeterol, induce bronchodilation for at least 12 hours44 and are used as a supplementary therapy for asthma that is not controlled by inhaled corticosteroids. It has also been proposed that LABAs increase the efficacy of inhaled corticosteroids45, although this is controversial. Monotherapy with a LABA is not recommended as it could mask worsening inflammation, with potentially serious consequences46. Increased patient adherence and convenience have led to the widespread use of combination inhalers containing inhaled corticosteroids and LABAs.

Mediator antagonists and synthesis inhibitors. H1-antihistamines such as chlorpheniramine were the first specific agents used to treat allergic reactions. Although the early products were effective at controlling the symptoms of allergy, their sedative and anti-cholinergic side-effects were problematic. These have been overcome by the development of a second generation of drugs — including cetirizine, levocetirizine, loratadine and desloratadine — that have a decreased capacity to cross the blood–brain barrier, greater efficacy and selectivity, and decreased cardiac toxicity47. The CysLTs are some of the most potent contractile agonists of airway smooth muscle and they also have effects on microvessels, mucous glands, eosinophils and nerves by interacting with the CysLT receptor 1 (CysLTR1). During active asthma and rhinitis, increased levels of CysLTC4, CysLTD4 and CysLTE4 have been detected in biological fluids. Neither the biosynthesis nor the actions of CysLTs are inhibited by corticosteroids48. The currently available oral leukotriene modifiers are CysLTR1 antagonists (montelukast, zafirlukast and pranlukast), but despite numerous attempts, only one 5-lipoxygenase inhibitor, zileuton, has so far passed clinical trials49. Although CysLTR antagonists can be used as a monotherapy in mild to moderate asthma (particularly in children), their main use is as a supplementary therapy to inhaled corticosteroids50. Leukotriene inhibitors are also effective for the treatment of allergic rhinoconjunctivitis (which frequently coexists with asthma)51, but not for the treatment of atopic dermatitis52.

Phosphodiesterase inhibitors. Theophylline is a xanthine with activity as both a cAMP phosphodiesterase (PDE) inhibitor and an adenosine-receptor antagonist. Theophylline has been used to treat asthmatic bronchoconstriction, but the cardiac and central-nervous-system side-effects that occur at doses similar to those required to generate therapeutic effects (low therapeutic index) have led to a marked reduction in its use. Although it has been proposed that theophylline also has some anti-inflammatory effect, the evidence is rather weak. More effective PDE inhibition has been achieved by targeting the type-4 isoenzyme with non-xanthine drugs such as rofumulast53.

Drugs for refractory disease. There are some patients with asthma whose symptoms are not adequately controlled by conventional treatments. Lack of adherence to treatment is an important cause, but otherwise refractory asthma sometimes responds to immunomodulators such as low-dose methotrexate, azathioprine or cyclosporine. However, randomized, controlled trials of these immunomodulators have given mixed results and side-effects are common54. By contrast, calcineurin inhibitors that inhibit T-cell responses, such as oral cyclosporine A and locally applied tacrolimus and pimecrolimus, are effective treatments for atopic dermatitis that is refractory to corticosteroid treatment55.

The failure of corticosteroids to decrease the level of expression of tumour-necrosis factor (TNF) and other TH1-cell-associated cytokines in asthmatic airways might explain why corticosteroids have limited effects in more severe forms of the disease56. Based on the increased expression of TNF in the airways57 and in blood mononuclear cells58 in severe asthma, two small studies have reported the efficacy of the soluble TNF-receptor fusion protein etanercept57,59. Large multi-centre trials with etanercept and TNF-specific monoclonal antibodies are now in progress. Inhibitors of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase and IκB kinase (IKK), such as SB 220025 (Ref. 60) and TPCA-1 (Ref. 61) respectively, are also attractive new therapeutic approaches for refractory asthma, as a result of their ability to inhibit the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF and IL-1.

Allergen-specific immunotherapy

Allergen-specific immunotherapy (SIT) is an immune-modifying therapy that has been recommended for the treatment of allergic rhinitis, venom hypersensitivity, some drug allergies and mild bronchial asthma. SIT induces immunological tolerance and the induction of blocking IgG4 antibodies through repeated exposure to allergen(s). After experimental or natural exposure to allergens, SIT decreases the recruitment of mast cells, basophils and eosinophils in the skin, nose, eye and bronchial mucosa (Fig. 4). SIT produces an increase in the level of allergen-specific IgA and IgG4 antibodies, and a decrease in the level of allergen-specific IgE antibodies. It also induces CD4+CD25+FOXP3+ TReg cells that produce high levels of IL-10 and/or TGFβ, two cytokines that are known to attenuate allergen-specific TH2-cell responses. IL-10 suppresses mast-cell, eosinophil and T-cell responses62, and the pleiotropic functions of TGFβ maintain a diverse and self-tolerant T-cell repertoire, including TReg cells63.

SIT modifies cellular and humoral responses to allergen. The ratio of T helper 1 (TH1)-cell cytokines to TH2-cell cytokines is increased after SIT, and functional regulatory T (TReg) cells are induced. The production of interleukin-10 (IL-10) by monocytes, macrophages, B cells and T cells is increased. The production of transforming growth factor-β (TGFβ) is increased and, together with IL-10, TGFβ might contribute to TReg-cell function and immunoglobulin class-switching to IgA, IgG1 and IgG4. These immunoglobulins compete with IgE for allergen binding, thereby decreasing the allergen capture and presentation that is facilitated by IgE in complex with the high-affinity receptor for IgE (FcɛRI) or the low-affinity receptor for IgE (FcɛRII, CD23). In addition, SIT decreases the number of mast cells and the ability of mast cells to release mediators. The recruitment of eosinophils and neutrophils to sites of allergen exposure is also decreased.

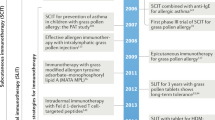

Subcutaneous immunotherapy (SCIT) involves the regular subcutaneous injection of allergen extracts or recombinant allergens using incremental regimes, with the induction of tolerance taking from several days to several months depending on the regime used. The usual approach is a build-up phase (consisting of weekly injections) followed by a maintenance phase (consisting of monthly injections). Once tolerance is induced it can last for several years without further treatment64. The limiting factor in SCIT is anaphylactic side-effects, which vary in incidence from 0.1-5% of individuals depending on severity65. Improved efficacy with decreased side-effects is the aim of the new approaches to SCIT, including T-cell-reactive peptides66, hypoallergenic recombinant allergens67, chemically modified allergens (allergoids)68, replacing adjuvants such as alum with those containing tyrosine or calcium phosphate, incorporation of immunomodulators such as monophosphoryl lipid A (MPL)69, and embedding of allergens into nanoparticles70. Attaching CpG oligonucleotide motifs to purified allergens seems to be a particularly promising approach to SCIT by increasing the efficacy and decreasing the side effects, as recently reported for the novel ragweed-allergen conjugate71.

The administration of allergens to the oral mucosa as a route for immunotherapy has only recently gained acceptance (sublingual immunotherapy, SLIT). Although much higher doses of allergen are required than are used for SCIT, the side-effect profile is impressively mild, making this therapy an attractive alternative and suitable for children72,73. Several clinical trials and meta-analyses show that SLIT is effective for the treatment of pollenosis caused by grass, Parietaria judaica, olive, ragweed and birch, as well as rhinitis that is associated with house-dust-mite and cat allergies, but the benefit is less than that of topical corticosteroids and antihistamines74.

The efficacy and safety of SCIT in patients with allergic asthma is controversial. In the 2003 Cochrane review of 75 trials covering a total of 3,188 patients with asthma, SCIT led to a significant reduction in asthma symptom scores, medication use and airway hyper-responsiveness, with evidence of a dose-related effect75. Dose-response studies carried out for dog76, cat77, ragweed78 and grass79 allergies show consistent efficacy of SCIT for between 5 and 20 mcg of the major allergen.

SCIT and SLIT also decrease the development of sensitization to new allergens and decrease the risk of new asthma in both adults and children with rhinitis. A significantly decreased rate for the development of new allergen sensitizations has been shown in monosensitized patients who received SCIT compared with untreated, matched controls80,81,82. Several studies have indicated that allergic rhinitis often precedes asthma and therefore that rhinitis might be an important risk factor for the development of asthma83,84. A recent retrospective cohort study of 332 subjects with allergic rhinitis showed that 53.1% of subjects who were not treated with SCIT developed asthma, whereas 41.6% of subjects who received SCIT were diagnosed with asthma at the end of the observation period84. The observed effect of SCIT in decreasing the incidence of new asthma cases is of clinical importance, with a significant reduction in the prevalence of physician-diagnosed asthma in adults with allergic rhinitis. These findings seem to be in agreement with the results of a ground-breaking, prospective, multicentre study (the PAT study) of 205 children with a clinical history of grass- or birch-induced rhinoconjunctivitis, who were randomized to receive SCIT for 3 years or to an open control group85. There was a statistically significant decrease in risk for the development of asthma during the treatment period (odds ratio, 2.52 in favour of SCIT for the prevention of asthma). At the 5-year follow-up (2 years after discontinuation of SCIT), the preventive effect of SCIT was still evident. Of the 142 children without asthma before the start of the study, those that had received SCIT had significantly less asthma than those in the control group: 16/48 with asthma in the SCIT group compared with 24/29 in the untreated control group (odds ratio, 2.68 in favour of SCIT for the prevention of asthma)86. In a randomized, placebo-controlled 3-year study of allergen immunotherapy in non-asthmatic, rhinitic adults monosensitized to Parietaria pollen, it was reported that 47% of patients in the placebo group developed asthma symptoms by the end of the study, compared with only 14% of the patients treated with SCIT87. This significant reduction in the incidence of new asthma cases seems to be confirmed also in studies with SLIT. In a recent prospective, multicentre study of 113 non-asthmatic children with a clinical history of hay fever to grass who were randomized to receive SLIT for 3 years or to an open control group, there was a statistically significant reduction in risk for the development of asthma during the treatment period (odds ratio, 3.8 in favour of SLIT for the prevention of asthma)88.

IgE as a therapeutic target

The sentinel role of IgE in increasing allergen uptake by DCs and activating mast cells and basophils for mediator release is reviewed in this issue by Hannah Gould and Brian Sutton89. IgG antibodies specific for the C3 domain of IgE that block IgE binding to FcɛRI (and FcɛRII, CD23) were shown to inhibit allergen-induced inflammatory responses in mice and in humans90. Omalizumab, a humanized IgE-specific, non-anaphylactic IgG1 has been developed for the treatment of severe allergic asthma91 (Fig. 5). Clinical trials in adults, adolescents and children with poorly controlled IgE-mediated asthma have shown that omalizumab administered subcutaneously 2–4 times per week (in proportion to the total level of IgE in the patient's serum and to the patient's body weight) improves symptom control and allows patients to be managed with lower doses of inhaled corticosteroids. Omalizumab has been well-tolerated in clinical trials lasting as long as 52 weeks. Although the level of circulating free IgE decreases rapidly after the first dose of omalizumab, up to 16 weeks of treatment is required before optimal clinical effects are seen. Omalizumab is also effective for the treatment of allergic rhinoconjunctivitis, but therapy has to begin long before the pollen season92,93. There is interest in developing a peptide-based vaccine for active immunization to elicit long-term, protective, IgE-specific antibodies. In sensitized rats, autoantibodies specific for IgE can be induced by IgE peptide-based vaccines94. RP01, a novel immunotherapeutic that induces the production of IgE-specific antibodies, has just entered Phase II clinical trials for allergic asthma95. Lumiliximab, an antibody specific for the low-affinity IgE receptor FcɛRII, also decreases circulating IgE levels and has passed Phase 1 trials for mild to moderate allergic asthma96.

The monoclonal IgE-specific antibody omalizumab can decrease free IgE levels and decrease the amount of IgE binding to both high-affinity (FcɛRI) and low-affinity (FcɛRII) IgE receptors, resulting in an attenuation of allergic reactions. In addition to inhibiting the binding of IgE to mast cells, basophils and eosinophils, omalizumab downregulates the expression of FcɛRI. This will also decrease the amplification of the inflammatory response mediated by T helper cells to prevent IgE-dependent allergen presentation.

Inhibitors of mast cells

The archetypal mast-cell-stabilizing drug sodium cromoglicate (SCG) was first introduced as a treatment for asthma in 1968 and was followed by nedocromil sodium in 1984 (Ref. 97). After inhalation, both drugs inhibit the allergen-induced early- and late-phase responses in the upper and lower airways and conjunctiva, where mucosal mast cells are crucially involved in the allergic response98. Nedocromil sodium and SCG inhibit the flux of chloride ions in mast cells, epithelial cells and neurons to increase their threshold for activation99. Human mast cells also express a Ca2+-activated K+ channel — K(Ca)3.1 — that promotes mast-cell chemotaxis and increases IgE-dependent mast-cell activation, which indicates that the inhibition of K(Ca)3.1 with drugs such as clotrimazole and TRAM-34 (1-[(2-chlorophenyl) diphenylmethyl]-1H-pyrazole) might be a new approach to mast-cell inhibition100,101.

Another newly identified cell-surface target on mast cells is CD63, a member of the tetraspanin family of proteins. CD63 interferes with integrin signalling, localization or trafficking and interacts with the α3, α4 and α6 chains of β1 integrins to modify adhesion to fibronectin and vitronectin102. A monoclonal antibody that blocks CD63 inhibits FcɛRI-mediated activation of mast cells that are adherent to extracellular matrix proteins but not of nonadherent cells.

The SRC tyrosine kinases FYN and LYN are important modulators of the molecular events that are initiated by engagement of FcɛRI103. A novel strategy to inhibit mast-cell activation is to inactivate the SYK that propagates FcɛRI signalling104. A cell-based, high-throughput screen for small molecules that block IgE signalling identified a 2,4-diaminopyrimidine (R112) as a reversible mast-cell SYK inhibitor105. In allergic rhinitis, intranasal administration of R112 followed by allergen challenge inhibited nasal obstruction and rhinorrhoea, together with the inhibition of prostaglandin D2 production106. In patients with seasonal rhinitis who were exposed for 2 days to a high pollen count, R112 was effective in reducing global symptoms of rhinitis with rapid onset107.

The interaction of stem-cell factor (SCF) with its tyrosine-kinase receptor KIT is obligatory for mast-cell development, proliferation, survival, homing and adhesion, and for optimal IgE-induced mast-cell degranulation and cytokine production108. Drug candidates that target SCF or KIT include SCF-specific antibodies, antisense oligonucleotides, KIT inhibitors and inhibitors of downstream signalling molecules109. Imatinib mesylate (imatinib), nilotinib and dasatinib are tyrosine-kinase inhibitors that were developed to treat BCR–ABL-expressing leukaemia and gastrointestinal stromal tumours. By also inhibiting a mutant form of KIT, they induce the apoptosis of mast cells, which is of value in the treatment of some forms of systemic mastocytosis. This approach is also being evaluated for treating allergic disease110.

Modulating the expression of activating and inhibitory receptors is an important mechanism for regulating immune responses. Cells that are activated through ligation of receptors bearing immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motifs (ITAMs) can be negatively regulated by other receptors bearing immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibitory motifs (ITIMs)111. Animals that are deficient in some of these ITIM-containing receptors — for example, animals that are deficient in FcγRIIB, gp49B1 (LILRB4) or paired immunoglobulin-like receptor B (PIRB) — have increased allergic responses112. IgG can completely suppress IgE-mediated anaphylaxis by interacting with FcγRIIB113, which leads to activation of the SRC homology 2 (SH2)-domain-containing inositol polyphosphate 5′-phosphatase (SHIP) through recruitment of DOK (docking protein) and RasGAP to FcɛRI114. Similar inhibitory mechanisms are invoked when gp49B1 on mast cells is activated by its integrin ligand, αvβ3 (Ref. 115). So, the immunoglobulin-like receptors and their intracellular signalling molecules provide important new therapeutic targets to inhibit mast cells, as well as T cells, involved in the allergic cascade. A human bifunctional Fcγ–Fcɛ fusion protein designed to crosslink FcγRIIB and FcɛRI on human mast cells and basophils inhibits IgE-dependent degranulation and allergic reactions in mice transgenic for human FcɛRIα116. A chimeric human–cat Fcγ–Fel d 1 fusion protein inhibits allergic responses in mice sensitized to the major cat allergen Fel d 1, and this strategy therefore has potential as an enhanced form of immunotherapy117.

Cytokine-based immunotherapies

Because of the sentinel role that TH2 cytokines have in orchestrating allergic inflammation, they and their receptors are key therapeutic targets (Fig. 6). With almost no exceptions, this approach has required the application of biological agents in the form of blocking monoclonal antibodies, fusion proteins and, most recently, inhibitors of the TH2-cell transcription factors STAT6 (signal transducer and activator of transcription 6) and GATA3.

Allergic inflammation has been characterized as a mainly T helper 2 (TH2)-cell disease; therefore, efforts to alter the TH2–TH1-cell balance in asthma have been aggressively pursued, either by inhibiting TH2-cell cytokines (in particular, interleukin-4 (IL-4), IL-13 and IL-5) or promoting TH1-cell responses (interferon-γ (IFNγ) and IL-12). Inhibition of the allergic component of atopic asthma can also be achieved using IgE-specific monoclonal antibodies. APC, antigen-presenting cell; FceRI, high-affinity receptor for IgE; rh, recombinant human; TCR, T-cell receptor.

IL-4. Both IL-4 and IL-13 have a crucial role in the immunoglobulin isotype switching of B cells to produce IgE, whereas IL-4 alone is crucial for maintaining the TH2-cell phenotype, which makes both cytokines attractive therapeutic targets. A large number of animal studies have shown that blocking production or inhibiting the effects of IL-4 has profound effects on the allergic phenotype. A soluble, recombinant, human IL-4 receptor (altrakincept) consists of the extracellular portion of human IL-4Rα and is non-immunogenic. A small proof-of-concept trial of nebulized inhaled altrakincept for 12 weeks in patients with mild to moderate asthma indicated efficacy by allowing withdrawal from treatment with inhaled corticosteroids without relapse118, and this result was subsequently confirmed in a larger trial119. However, a Phase III trial failed to confirm the efficacy of altrakincept for the treatment of asthma. This trial does not invalidate IL-4 as a target for the treatment of allergy and asthma, as there were concerns over the bioavailability of altrakincept in this study. Further Phase II studies are in progress using humanized IL-4-specific and IL-4Rα-blocking antibodies such as pascolizumab (SB240,683)120. Two vaccines against IL-4 have been tested in mice, one in which IL-4 is chemically coupled to limpet haemocyanin121 and the other in which a 14-amino-acid peptide from IL-4 is inserted into variant hepatitis B virus core antigen122. Both vaccines induced high antibody titres specific for mouse IL-4 and inhibited antigen-induced lung inflammation. However, using co-stimulation blockade in a mouse model of allergy to grass pollen123, it was reported that the secondary IgE response is not T-cell dependent, thereby raising doubts over the usefulness of IL-4 blockade for treating established allergic disease.

IL-13. The numerous functions of IL-13 in regulating IgE production, eosinophilic inflammation, airway-smooth-muscle hyperplasia, the induction of goblet-cell hyperplasia with mucus production, and the recruitment of monocytes, macrophages and T cells into the airway spaces make it a key therapeutic target in allergy and asthma124. IL-13 binds to a low-affinity IL-13Rα1 subunit and a high-affinity complex comprised of IL-13Rα1 and IL-4Rα. Binding to this high-affinity complex leads to the phosphorylation-dependent activation of Janus kinase 1 (JAK1), JAK2 and STAT6. IL-4Rα also stabilizes the binding of IL-13 to its receptor to augment IL-13-mediated responses. However, a non-signalling, high-affinity IL-13-binding chain, IL-13Rα2, strongly inhibits the activity of IL-13 (Ref. 125). Selective blockade of IL-13 has been achieved in mice using a soluble form of IL-13Rα2, which competes for binding to IL-13 but not to IL-4, and this led to the reversal of airway hyper-responsiveness and mucus production in allergen-exposed sensitized mice126. A soluble form of IL-13Rα2 that binds IL-13 with 100-fold greater affinity than does IL-13Rα1 is present in mouse but not human serum.

Antagonizing the effects of IL-13 could also be achieved by administering soluble IL-13 receptors or IL-13R-specific monoclonal antibodies. In cynomolgus monkeys sensitized to Ascaris suum and then challenged with antigen from this nematode, a mouse antibody specific for human IL-13 (mAb13.2) and the humanized counterpart (IMA-638) inhibited eosinophil and neutrophil influx into the lungs as assessed by bronchoalveolar lavage127. Phase I trials of the IL-13-specific monoclonal antibody CAT-354 in 34 mildly asthmatic patients have been successfully completed and Phase II trials are in progress. Subcutaneous or inhaled pitrakinra, a mutant IL-4 protein that inhibits the binding of IL-4 and IL-13 to IL-4Rα complexes, has recently shown efficacy in the treatment of allergen-induced asthma128. A novel, recombinant IL-13 peptide-based vaccine has also been shown to reduce allergic inflammatory responses in mice129. As STAT6 is the common transcription factor for both IL-4 and IL-13 signalling, it is also an attractive therapeutic target using a dominant-negative peptide130 and anti-sense RNA-based approaches. Anti-sense and RNA-interference-based therapeutic strategies are being explored to target various upstream signalling molecules in asthma and allergy, including FcɛRIα, cytokine receptors, adhesion molecules, ion channels, cytokines and related factors, intracellular signal-transduction molecules and transcription factors involved in TH2-cell differentiation and allergic inflammation131.

IL-5. Rodent and non-human primate studies have indicated an important role for IL-5 in various models of asthma. Inhaled IL-5 modulates the number of eosinophil progenitors in both the airways and bone marrow of asthmatic individuals and induces local eosinophilia in non-asthmatic individuals132. Two humanized, human-IL-5-specific monoclonal antibodies, Sch-55,700 and mepolizumab (SB-240,563), have been developed for the treatment of asthma. In a small, double-blind trial, mepolizumab produced a rapid dose-dependent reduction in the number of circulating and sputum eosinophils that persisted for 3 months but, surprisingly, this had no effect on either the late asthmatic response or on airway hyper-responsiveness133. In a group of patients with severe persistent asthma, treatment with Sch-55,700 resulted in a decrease in the number of blood eosinophils, but over the course of 10 weeks it had no effect on any measures of asthma outcome134, an observation that has recently been confirmed in a large trial with mepolizumab135.

A further study using mepolizumab confirmed the persistent suppression of eosinophilia in blood, bone marrow and airway lavage, but in airway biopsies, there was only a 55% reduction in the number of tissue eosinophils136. As a proportion of eosinophils in the airways of patients with asthma lack IL-5R137,138, it was suggested that this might explain the apparent lack of clinical efficacy of targeting IL-5 (Ref. 139). IL-5 could have more subtle effects on asthmatic airways — for example, mepolizumab treatment decreases immunostaining for tenascin, lumican and procollagen III in the bronchial mucosal subepithelial basal lamina140 and in allergen-challenged skin141. In addition, IL-5-specific treatment resulted in a parallel decrease in the number of airway eosinophils expressing mRNA for TGFβ1 and of TGFβ1 levels in bronchoalveolar-lavage fluid, which indicates a possible role for IL-5 in airway remodelling142. In contrast to asthma, mepolizumab is highly efficacious in the treatment of hypereosinophilic syndrome143 and eosinophilic oesophagitis144, but not atopic dermatitis145. A therapeutic DNA-based vaccine against IL-5 is also being developed.

IL-9. Blocking the actions of IL-9 reduces allergen-induced airway inflammation and airway hyper-responsiveness in mouse models. Two Phase I dose-escalation studies of an IL-9-specific monoclonal antibody (MEDI-528) in healthy volunteers have been completed without problems146. Phase II trials are in progress for treating symptomatic, moderate to severe, persistent asthma.

Interferons. Of the TH1-cell-associated cytokines, IFNγ is the most potent in suppressing TH2-cell-mediated allergic inflammation, and the exogenous administration of IFNγ suppresses allergic airway inflammation in animal models. IFNγ is also strongly induced during allergen-specific immunotherapy. However, studies of the subcutaneous administration of recombinant human IFNγ in asthma have been disappointing147. In mice, increased production of IFNγ together with an established TH2-cell response results in increased inflammation, possibly by damaging the epithelial barrier148. By contrast, two small trials have shown that systemic administration of IFNγ for 18 months is effective for the treatment of severe corticosteroid-refractory asthma, with one study showing reversal of the TH2-cell cytokine profile in blood mononuclear cells after treatment of patients with severe asthma149,150.

The recent demonstration that epithelial cells from asthmatic individuals in vitro have an impaired protective IFNb response to infection with the common cold virus151,152 has prompted clinical trials of recombinant human IFNb by inhalation to prevent severe virus-induced asthma exacerbations153.

IL-12. IL-12 sends a powerful signal to naive precursor T cells, directing their differentiation to TH1 cells in vitro and in vivo and shifting the immune response towards cell-mediated immunity. In animal models, administration of IL-12 during sensitization suppresses allergen-induced TH2-cell responses in favour of TH1-cell development and inhibits airway hyper-responsiveness and airway eosinophilia after antigen challenge. In asthma, the production of IL-12 by whole blood cells and its expression in airway biopsies is impaired. So, IL-12 has the potential to modify allergic diseases. Injection of recombinant human IL-12 in patients with mild asthma decreased the number of circulating blood eosinophils after allergen challenge (but not sputum eosinophilia, the late-phase response or airway hyper-responsiveness)154 and this was accompanied by flu-like symptoms, abnormal liver-function tests and cardiac arrhythmias. This approach is also brought into question by the observation that in mice, DCs retrovirally overexpressing IL-12 induce strong TH1-cell responses to inhaled antigen in the lung but fail to suppress TH2-cell polarization after sensitization155.

IL-10. IL-10 inhibits the expression of many pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, as well as pro-inflammatory enzymes, and it is the main inhibitory cytokine produced by TReg cells in allergen immunotherapy. IL-10-deficient mice have increased airway inflammation after allergen challenge156, and in outbred mice, this was inhibited by the intratracheal transfer of the gene encoding IL-10 (Ref. 157). Administration of IL-10 to normal volunteers decreases the numbers of circulating CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, with suppression of mitogen-induced T-cell proliferation and endotoxin-driven TNF and IL-1β production158. Recombinant human IL-10 has been developed and is currently being tested in rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, psoriasis, organ transplantation and chronic hepatitis C, but its effect in asthma has yet to be studied.

Targeting barrier function

The increased access of allergens to immune cells in the skin could explain the convincing association between loss-of-function mutations of the barrier protein filaggrin and the increased occurrence of atopic dermatitis159. In the case of asthma, impaired barrier function is a consequence of defective tight-junction assembly25, which can be restored both in human cells in vitro and in a mouse model in vivo160 by the topical application of epidermal growth factor or keratinocyte growth factor. The restoration of barrier function by growth-factor administration has been highly successful in the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease161 and oral mucositis associated with cytotoxic therapy162.

Concluding remarks

Despite an enormous increase in our understanding of the immune mechanisms involved in allergic diseases, it is disappointing that this knowledge has not been translated into new treatments. One possible reason for this is our lack of understanding of disease chronicity and the environmental factors that contribute to disease in addition to allergen exposure. The recent success of omalizumab as the first biological agent for the treatment of allergy opens new opportunities for using biological agents to target specific cytokines and cell-surface proteins that are involved in the allergic cascade, such as CCR4 in TH2-cell recruitment163, and TSLP and IL-25, which link the epithelium with DC activation and the TH2-cell response. Several new cytokine therapeutic targets are shown in Table 1.

The chemical engineering of monoclonal antibodies to increase their antibody-dependent cytotoxic potential seems to be a particularly promising approach when directed against cells expressing TH2-cell markers such as IL-5R and CCR4 (Ref. 164). Vaccine approaches to allergy prevention and treatment are developing rapidly. In addition to the use of recombinant allergens and peptide fragments to increase efficacy and decrease side-effects, the coupling of allergens to oligonucleotide stimulatory sequences such as CpG DNA and other ligands of pathogen-recognition receptors to tip the balance towards a TH1-cell response, and the development of allergen-based DNA vaccines will revolutionize allergen immunotherapy. Vaccine strategies are also looking promising for generating endogenous blocking antibodies specific for targets that are known to be involved in the allergic phenotype. As tissue injury and aberrant repair are an important component of chronic allergic diseases such as asthma, attempts are now being made to develop new therapeutic approaches to target these aspects, an example of which is bronchial thermoplasty, which removes airway smooth muscle in asthma165. However, what is now needed is a clearer understanding of the origins of allergy and the factors responsible for the increasing incidence of allergic diseases with a view to developing preventive, as well as therapeutic, strategies.

References

Georas, S. N., Guo, J., De, F. U. & Casolaro, V. T-helper cell type-2 regulation in allergic disease. Eur. Respir. J. 26, 1119–1137 (2005).

Sicherer, S. H. & Sampson, H. A. Peanut allergy: emerging concepts and approaches for an apparent epidemic. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 120, 491–503 (2007).

Asher, M. I. et al. Worldwide time trends in the prevalence of symptoms of asthma, allergic rhinoconjunctivitis, and eczema in childhood: ISAAC Phases One and Three repeat multicountry cross-sectional surveys. Lancet 368, 733–743 (2006).

Ishizaka, K., Ishizaka, T. & Hornbrook, M. M. Physicochemical properties of reaginic antibody. V. Correlation of reaginic activity wth γ-E-globulin antibody. J. Immunol. 97, 840–853 (1966).

Eder, W., Ege, M. J. & von Mutius, E. The asthma epidemic. N. Engl. J. Med. 355, 2226–2235 (2006).

Hammad, H. & Lambrecht, B. N. Recent progress in the biology of airway dendritic cells and implications for understanding the regulation of asthmatic inflammation. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 118, 331–336 (2006).

Glimcher, L. H. Trawling for treasure: tales of T-bet. Nature Immunol. 8, 448–450 (2007).

Hammad, H. & Lambrecht, B. N. Dendritic cells and epithelial cells: linking innate and adaptive immunity in asthma. Nature Rev. Immunol. (in the press).

von Garnier, C. et al. Allergic airways disease develops after an increase in allergen capture and processing in the airway mucosa. J. Immunol. 179, 5748–5759 (2007).

Cousins, D. J., Lee, T. H. & Staynov, D. Z. Cytokine coexpression during human TH1/TH2 cell differentiation: direct evidence for coordinated expression of TH2 cytokines. J. Immunol. 169, 2498–2506 (2002).

Romagnani, S. Regulation of the T-cell response. Clin. Exp. Allergy 36, 1357–1366 (2006).

Wing, K., Fehervari, Z. & Sakaguchi, S. Emerging possibilities in the development and function of regulatory T cells. Int. Immunol. 18, 991–1000 (2006).

Seddiki, N. et al. Expression of interleukin (IL)-2 and IL-7 receptors discriminates between human regulatory and activated T cells. J. Exp. Med. 203, 1693–1700 (2006).

Bacchetta, R., Gambineri, E. & Roncarolo, M. G. Role of regulatory T cells and FOXP3 in human diseases. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 120, 227–235 (2007).

Larche, M. Regulatory T cells in allergy and asthma. Chest 132, 1007–1014 (2007).

Stockinger, B. TH17 cells: an orphan with influence. Immunol. Cell Biol. 85, 83–84 (2007).

Chen, Z., Tato, C. M., Muul, L., Laurence. A. & O'Shea, J. J. Distinct regulation of interleukin-17 in human T helper lymphocytes. Arthritis Rheum. 56, 2936–2946 (2007).

Bullens, D. M. et al. IL-17 mRNA in sputum of asthmatic patients: linking T cell driven inflammation and granulocytic influx? Respir. Res. 7, 135 (2006).

Dragon, S. et al. IL-17 enhances IL-1β-mediated CXCL8 release from human airway smooth muscle cells. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 292, L1023–L1029 (2007).

Cockcroft, D. W., Hargreave, F. E., O'Byrne, P. M. & Boulet, L. P. Understanding allergic asthma from allergen inhalation tests. Can. Respir. J. 14, 414–418 (2007).

Kelly, M., Hwang, J. M. & Kubes, P. Modulating leukocyte recruitment in inflammation. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 120, 3–10 (2007). An important review that describes the molecular mechanisms of the leukocyte-recruitment cascade. It includes most of the important original papers in this field.

Palmqvist, C., Wardlaw, A. J. & Bradding, P. Chemokines and their receptors as potential targets for the treatment of asthma. Br. J. Pharmacol. 151, 725–736 (2007).

Pease, J. E. & Williams, T. J. The attraction of chemokines as a target for specific anti-inflammatory therapy. Br. J. Pharmacol. 147 (Suppl. 1), S212–S221 (2006).

Schleimer, R. P., Kato, A., Kern, R., Kuperman, D. & Avila, P. C. Epithelium: at the interface of innate and adaptive immune responses. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 120, 1279–1284 (2007). This review discusses recent studies that have looked at the molecular and cellular mechanisms by which epithelial cells help to shape the immune and inflammatory responses of dendritic cells, T cells and B cells, and inflammatory-cell recruitment in the context of human disease.

Holgate, S. T. The epithelium takes centre stage in asthma and atopic dermatitis. Trends Immunol. 28, 248–251 (2007).

Bucchieri, F. et al. Asthmatic bronchial epithelium is more susceptible to oxidant-induced apoptosis. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 27, 179–185 (2002).

Davies, D. E., Wicks, J., Powell, R. M., Puddicombe, S. M. & Holgate, S. T. Airway remodeling in asthma: new insights. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 111, 215–225 (2003). A provocative review that discusses an alternative view of asthma pathogenesis by emphasizing the crucial role played by the airway microenvironment and by changes due to remodelling.

Klunker, S. et al. A second step of chemotaxis after transendothelial migration: keratinocytes undergoing apoptosis release IFN-γ-inducible protein 10, monokine induced by IFN-γ, and IFN-γ-inducible α-chemoattractant for T cell chemotaxis toward epidermis in atopic dermatitis. J. Immunol. 171, 1078–1084 (2003).

Illi, S. et al. Perennial allergen sensitisation early in life and chronic asthma in children: a birth cohort study. Lancet 368, 763–770 (2006). This large, prospective, multicentre study investigates the role of allergic sensitization and allergen exposure early in life and shows that sensitization to perennial allergens developing in the first 3 years of life is associated with a loss of lung function and increased the development of airway hyper-responsiveness at school age.

Corver, K. et al. House dust mite allergen reduction and allergy at 4 yr: follow up of the PIAMA-study. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 17, 329–336 (2006).

Woodcock, A. et al. Early life environmental control: effect on symptoms, sensitization, and lung function at age 3 years. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 170, 433–439 (2004).

Arshad, S. H., Bateman, B., Sadeghnejad, A., Gant, C. & Matthews, S. M. Prevention of allergic disease during childhood by allergen avoidance: the Isle of Wight prevention study. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 119, 307–313 (2007).

Turcanu, V., Maleki, S. J. & Lack, G. Characterization of lymphocyte responses to peanuts in normal children, peanut-allergic children, and allergic children who acquired tolerance to peanuts. J. Clin. Invest. 111, 1065–1072 (2003).

Holt, P. G. & Sly, P. D. Prevention of allergic respiratory disease in infants: current aspects and future perspectives. Curr. Opin. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 7, 547–555 (2007).

Woodcock, A. et al. Control of exposure to mite allergen and allergen-impermeable bed covers for adults with asthma. N. Engl. J. Med. 349, 225–236 (2003).

Terreehorst, I. et al. Evaluation of impermeable covers for bedding in patients with allergic rhinitis. N. Engl. J. Med. 349, 237–246 (2003).

Barnes, P. J., Chung, K. F. & Page, C. P. Inflammatory mediators of asthma: an update. Pharmacol. Rev. 50, 515–596 (1998).

Barnes, P. J. & Adcock, I. M. Transcription factors and asthma. Eur. Respir. J. 12, 221–234 (1998).

Barnes, P. J. & Adcock, I. M. How do corticosteroids work in asthma? Ann. Intern. Med. 139, 359–370 (2003). This article summarizes recent developments in our understanding of the fundamental mechanisms of gene transcription, which have led to important advances in our understanding of the molecular mechanisms by which corticosteroids suppress inflammation and provide insights into why corticosteroids fail to work in patients with steroid-resistant asthma.

Bisgaard, H., Hermansen, M. N., Loland, L., Halkjaer, L. B. & Buchvald, F. Intermittent inhaled corticosteroids in infants with episodic wheezing. N. Engl. J. Med. 354, 1998–2005 (2006).

Guilbert, T. W. et al. Long-term inhaled corticosteroids in preschool children at high risk for asthma. N. Engl. J. Med. 354, 1985–1997 (2006). References 40 and 41 are large, controlled, prospective studies that provide decisive evidence that early anti-inflammatory therapy with inhaled corticosteroids in pre-school children at high risk for asthma fails to modify the natural course of the disease.

Harrison, T. W., Oborne, J., Newton, S. & Tattersfield, A. E. Doubling the dose of inhaled corticosteroid to prevent asthma exacerbations: randomised controlled trial. Lancet 363, 271–275 (2004).

Chaudhuri, R. et al. Cigarette smoking impairs the therapeutic response to oral corticosteroids in chronic asthma. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 168, 1308–1311 (2003).

Palmqvist, M. et al. Inhaled dry-powder formoterol and salmeterol in asthmatic patients: onset of action, duration of effect and potency. Eur. Respir. J. 10, 2484–2489 (1997).

Usmani, O. S. et al. Glucocorticoid receptor nuclear translocation in airway cells after inhaled combination therapy. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 172, 704–712 (2005).

Mcivor, R. A. et al. Potential masking effects of salmeterol on airway inflammation in asthma. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 158, 924–930 (1998).

Del, C. A. et al. Comparative pharmacology of the H1 antihistamines. J. Invest. Allergol. Clin. Immunol. 16 (Suppl 1), 3–12 (2006).

Gyllfors, P., Dahlen, S. E., Kumlin, M., Larsson, K. & Dahlen, B. Bronchial responsiveness to leukotriene D4 is resistant to inhaled fluticasone propionate. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 118, 78–83 (2006). A small clinical trial showing that fluticasone had a significant protective effect on bronchial responsiveness to methacholine but not LTD 4 , which provides evidence in favour of the theory that there is an additive therapeutic efficacy of anti-leukotrienes with inhaled corticosteroids in asthma.

Kemp, J. P. Recent advances in the management of asthma using leukotriene modifiers. Am. J. Respir. Med. 2, 139–156 (2003).

Polosa, R. Critical appraisal of antileukotriene use in asthma management. Curr. Opin. Pulm. Med. 13, 24–30 (2007).

Nayak, A. & Langdon, R. B. Montelukast in the treatment of allergic rhinitis: an evidence-based review. Drugs 67, 887–901 (2007).

Friedmann, P. S. et al. A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of montelukast in adult atopic eczema. Clin. Exp. Allergy 37, 1536–1540 (2007).

Boswell-Smith, V., Cazzola, M. & Page, C. P. Are phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitors just more theophylline? J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 117, 1237–1243 (2006).

Holgate, S. T. & Polosa, R. The mechanisms, diagnosis, and management of severe asthma in adults. Lancet. 368, 780–793 (2006).

Hijnen, D. J., Knol, E., Bruijnzeel-Koomen, C. & de Bruin-Weller, M. Cyclosporin A treatment is associated with increased serum immunoglobulin E levels in a subgroup of atopic dermatitis patients. Dermatitis 18, 163–165 (2007).

Truyen, E. et al. Evaluation of airway inflammation by quantitative TH1/TH2 cytokine mRNA measurement in sputum of asthma patients. Thorax 61, 202–208 (2006).

Howarth, P. H. et al. Tumour necrosis factor (TNFα) as a novel therapeutic target in symptomatic corticosteroid-dependent asthma. Thorax 60, 1012–1018 (2005).

Waserman, S., Dolovich, J., Conway, M. & Marshall, J. S. TNFα dysregulation in asthma: relationship to ongoing corticosteroid therapy. Can. Respir. J. 7, 229–237 (2000).

Berry, M. A. et al. Evidence of a role of tumor necrosis factor-α in refractory asthma. N. Engl. J. Med. 354, 697–708 (2006).

Duan, W. et al. Inhaled p38α mitogen-activated protein kinase antisense oligonucleotide attenuates asthma in mice. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 171, 571–578 (2005).

Birrell, M. A. et al. IκB kinase-2-independent and -dependent inflammation in airway disease models: relevance of IKK-2 inhibition to the clinic. Mol. Pharmacol. 69, 1791–1800 (2006). This was the first study to examine the effect of an IKK2 inhibitor (TPCA-1) in well-validated models that mimic aspects of airway inflammation. TPCA-1 blocked the increase in NF-κB binding to DNA with an associated decrease in the release of inflammatory mediators and in the inflammatory-cell burden in the lungs.

Wu, K., Bi, Y., Sun, K. & Wang, C. IL-10-producing type 1 regulatory T cells and allergy. Cell Mol. Immunol. 4, 269–275 (2007).

Wan, Y. Y. & Flavell, R. A. 'Yin-Yang' functions of transforming growth factor-β and T regulatory cells in immune regulation. Immunol. Rev. 220, 199–213 (2007).

Durham, S. R. et al. Long-term clinical efficacy of grass-pollen immunotherapy. N. Engl. J. Med. 341, 468–475 (1999).

Williams, A. P., Krishna, M. T. & Frew, A. J. The safety of immunotherapy. Clin. Exp. Allergy 34, 513–514 (2004).

Larché, M. Update on the current status of peptide immunotherapy. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 119, 906–909 (2007). This recent review summarizes the mechanisms by which allergen-specific immunotherapy exerts its immunological and anti-inflammatory effects. It also addresses new approaches to improve the efficacy of and decrease the incidence and severity of adverse reactions to allergen-specific immunotherapy.

Valenta, R. & Niederberger, V. Recombinant allergens for immunotherapy. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 119, 826–830 (2007).

Lund, L. et al. Comparison of allergenicity and immunogenicity of an intact allergen vaccine and commercially available allergoid products for birch pollen immunotherapy. Clin. Exp. Allergy 37, 564–571 (2007).

Wheeler, A. A novel adjuvant complex, tyrosine–MPL, for prophylactic and therapeutic vaccines. Vaccine 24 (Suppl. 2), 40–41 (2006).

Scholl, I., Kopp, T., Bohle, B. & Jensen-Jarolim, E. Biodegradable PLGA particles for improved systemic and mucosal treatment of Type I allergy. Immunol. Allergy Clin. North Am. 26, 349–364, ix (2006).

Creticos, P. S., Chen, Y. H. & Schroeder, J. T. New approaches in immunotherapy: allergen vaccination with immunostimulatory DNA. Immunol. Allergy Clin. North Am. 24, 569–581, v (2004).

Valovirta, E., Jacobsen, L., Ljorring, C., Koivikko, A. & Savolainen, J. Clinical efficacy and safety of sublingual immunotherapy with tree pollen extract in children. Allergy, 61, 1177–1183 (2006).

Ozdemir, C. et al. Efficacy of long-term sublingual immunotherapy as an adjunct to pharmacotherapy in house dust mite-allergic children with asthma. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 18, 508–515 (2007).

Pajno, G. B. Sublingual immunotherapy: the optimism and the issues. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 119, 796–801 (2007). A recent overview that highlights the pros and cons of sublingual immunotherapy for the treatment of patients with asthma and/or rhinitis. It also addresses new approaches to improve the treatment of patients with IgE-mediated food allergy and to modify the natural course of allergic diseases.

Abramson, M. J., Puy, R. M. & Weiner, J. M. Allergen immunotherapy for asthma. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. CD001186 (2003). This meta-analysis of 75 controlled trials (including a total of 3,188 participants with asthma) indicates that there is a significant reduction in asthma symptoms and medication and an improvement in bronchial hyper-reactivity after allergen immunotherapy.

Lent, A. M. et al. Immunologic response to administration of standardized dog allergen extract at differing doses. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 118, 1249–1256 (2006).

Ewbank, P. A. et al. A double-blind, placebo-controlled immunotherapy dose-response study with standardized cat extract. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 111, 155–161 (2003).

Creticos, P. S. et al. Nasal challenge with ragweed pollen in hay fever patients. Effect of immunotherapy. J. Clin. Invest. 76, 2247–2253 (1985).

Frew, A. J., Powell, R. J., Corrigan, C. J. & Durham, S. R. Efficacy and safety of specific immunotherapy with SQ allergen extract in treatment-resistant seasonal allergic rhinoconjunctivitis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 117, 319–325 (2006).

Des, R. A. et al. Immunotherapy with a standardized Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus extract. VI. Specific immunotherapy prevents the onset of new sensitizations in children. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 99, 450–453 (1997).

Purello-D'Ambrosio, F. et al. Prevention of new sensitizations in monosensitized subjects submitted to specific immunotherapy or not. A retrospective study. Clin. Exp. Allergy 31, 1295–1302 (2001).

Pajno, G. B., Barberio, G., De, L. F., Morabito, L. & Parmiani, S. Prevention of new sensitizations in asthmatic children monosensitized to house dust mite by specific immunotherapy. A six-year follow-up study. Clin. Exp. Allergy 31, 1392–1397 (2001).

Guerra, S., Sherrill, D. L., Martinez, F. D. & Barbee, R. A. Rhinitis as an independent risk factor for adult-onset asthma. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 109, 419–425 (2002).

Polosa, R., Al-Delaimy, W. K., Russo, C., Piccillo, G. & Sarva, M. Greater risk of incident asthma cases in adults with allergic rhinitis and effect of allergen immunotherapy: a retrospective cohort study. Respir. Res. 6, 153 (2005). This retrospective cohort study shows that allergic rhinitis is an important independent risk factor for asthma and that treatment with allergen immunotherapy was significantly and inversely related to the development of new-onset asthma in adults with allergic rhinitis.

Moller, C. et al. Pollen immunotherapy reduces the development of asthma in children with seasonal rhinoconjunctivitis (the PAT study). J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 109, 251–256 (2002).

Niggemann, B. et al. Five-year follow-up on the PAT study: specific immunotherapy and long-term prevention of asthma in children. Allergy 61, 855–859 (2006).

Polosa, R. et al. Effect of immunotherapy on asthma progression, BHR and sputum eosinophils in allergic rhinitis. Allergy 59, 1224–1228 (2004).

Novembre, E. et al. Coseasonal sublingual immunotherapy reduces the development of asthma in children with allergic rhinoconjunctivitis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 114, 851–857 (2004).

Gould, H. J. & Sutton, B. J. IgE in allergy and asthma today. Nature Rev. Immunol. (in the press).

Corne, J. et al. The effect of intravenous administration of a chimeric anti-IgE antibody on serum IgE levels in atopic subjects: efficacy, safety and pharmacokinetics. J. Clin. Invest. 99, 879–887 (1997).

Holgate, S. T., Djukanovic, R., Casale, T. & Bousquet, J. Anti-immunoglobulin E treatment with omalizumab in allergic diseases: an update on anti-inflammatory activity and clinical efficacy. Clin. Exp. Allergy 35, 408–416 (2005).

Plewako, H. et al. The effect of omalizumab on nasal allergic inflammation. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 110, 68–71 (2002).

Bez, C. et al. Effect of anti-immunoglobulin E on nasal inflammation in patients with seasonal allergic rhinoconjunctivitis. Clin. Exp. Allergy 34, 1079–1085 (2004).

Peng, Z. et al. Novel IgE peptide-based vaccine prevents the increase of IgE and down-regulates elevated IgE in rodents. Clin. Exp. Allergy 37, 1040–1048 (2007).

Vernersson, M., Ledin, A., Johansson, J. & Hellman, L. Generation of therapeutic antibody responses against IgE through vaccination. FASEB J. 16, 875–877 (2002).

Poole, J. A., Meng, J., Reff, M., Spellman, M. C. & Rosenwasser, L. J. Anti-CD23 monoclonal antibody, lumiliximab, inhibited allergen-induced responses in antigen-presenting cells and T cells from atopic subjects. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 116, 780–788 (2005).

Edwards, A. M. & Howell, J. B. The chromones: history, chemistry and clinical development. A tribute to the work of Dr R. E. C. Altounyan. Clin. Exp. Allergy 30, 756–774 (2000).

Bradding, P., Walls, A. F. & Holgate, S. T. The role of the mast cell in the pathophysiology of asthma. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 117, 1277–1284 (2006).

Alton, E. W. & Norris, A. A. Chloride transport and the actions of nedocromil sodium and cromolyn sodium in asthma 1. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 98, S102–S105 (1996).

Mark, D. S. et al. The K+ channel iKCA1 potentiates Ca2+ influx and degranulation in human lung mast cells. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 114, 66–72 (2004).

Cruse, G., Duffy, S. M., Brightling, C. E. & Bradding, P. Functional KCa3.1 K+ channels are required for human lung mast cell migration. Thorax 61, 880–885 (2006).

Kraft, S. et al. Anti-CD63 antibodies suppress IgE-dependent allergic reactions in vitro and in vivo. J. Exp. Med. 201, 385–396 (2005).

Kraft, S. & Kinet, J. P. New developments in FcɛRI regulation, function and inhibition. Nature Rev. Immunol. 7, 365–378 (2007).

Matsubara, S. et al. Inhibition of spleen tyrosine kinase prevents mast cell activation and airway hyperresponsiveness. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 173, 56–63 (2006).

Rossi, A. B. et al. Identification of the Syk kinase inhibitor R112 by a human mast cell screen. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 118, 749–755 (2006). References 103–105 focus on new therapeutic approaches to inhibit mast-cell activation through the modulation of Fc-receptor signalling. The use and the potential clinical application of chimeric fusion proteins, SRC tyrosine kinases and ATP-competitive SYK inhibitors are discussed.

Guyer, B. J. et al. Mast cell inhibitor R112 is well tolerated and affects prostaglandin D2 but not other mediators, symptoms, or nasal volumes in a nasal challenge model of allergic rhinitis. Allergy Asthma Proc. 27, 208–213 (2006).

Meltzer, E. O., Berkowitz, R. B. & Grossbard, E. B. An intranasal Syk-kinase inhibitor (R112) improves the symptoms of seasonal allergic rhinitis in a park environment. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 115, 791–796 (2005).

Okayama, Y. & Kawakami, T. Development, migration, and survival of mast cells. Immunol. Res. 34, 97–115 (2006).

Reber, L., Da Silva, C. A. & Frossard, N. Stem cell factor and its receptor c-Kit as targets for inflammatory diseases. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 533, 327–340 (2006).

Berlin, A. A., Hogaboam, C. M. & Lukacs, N. W. Inhibition of SCF attenuates peribronchial remodeling in chronic cockroach allergen-induced asthma. Lab. Invest. 86, 557–565 (2006).

Malbec, O. & Daeron, M. The mast cell IgG receptors and their roles in tissue inflammation. Immunol. Rev. 217, 206–221 (2007).

Daheshia, M., Friend, D. S., Grusby, M. J., Austen, K. F. & Katz, H. R. Increased severity of local and systemic anaphylactic reactions in gp49B1-deficient mice. J. Exp. Med. 194, 227–234 (2001).

Strait, R. T., Morris, S. C. & Finkelman, F. D. IgG-blocking antibodies inhibit IgE-mediated anaphylaxis in vivo through both antigen interception and FcγRIIb cross-linking. J. Clin. Invest. 116, 833–841 (2006).

Ott, V. L., Tamir, I., Niki, M., Pandolfi, P. P. & Cambier, J. C. Downstream of kinase, p62(dok), is a mediator of FcγIIB inhibition of FcɛRI signaling. J. Immunol. 168, 4430–4439 (2002).

Castells, M. C. et al. gp49B1–α(v)β3 interaction inhibits antigen-induced mast cell activation. Nature Immunol. 2, 436–442 (2001).

Allen, L. C., Kepley, C. L., Saxon, A. & Zhang, K. Modifications to an Fcγ–Fcvarɛ fusion protein alter its effectiveness in the inhibition of FcvarɛRI-mediated functions. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 120, 462–468 (2007).

Zhu, D. et al. A chimeric human–cat fusion protein blocks cat-induced allergy. Nature Med. 11, 446–449 (2005).

Borish, L. C. et al. Interleukin-4 receptor in moderate atopic asthma. A phase I/II randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 160, 1816–1823 (1999).

Borish, L. C. et al. Efficacy of soluble IL-4 receptor for the treatment of adults with asthma. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 107, 963–970 (2001).

Hart, T. K. et al. Preclinical efficacy and safety of pascolizumab (SB 240683): a humanized anti-interleukin-4 antibody with therapeutic potential in asthma. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 130, 93–100 (2002).

Le, B. H. et al. Control of allergic reactions in mice by an active anti-murine IL-4 immunization. Vaccine 25, 7206–7216 (2007).

Ma, Y. et al. Novel cytokine peptide-based vaccines: an interleukin-4 vaccine suppresses airway allergic responses in mice. Allergy 62, 675–682 (2007).

Linhart, B. et al. Costimulation blockade inhibits allergic sensitization but does not affect established allergy in a murine model of grass pollen allergy. J. Immunol. 178, 3924–3931 (2007).

Wynn, T. A. IL-13 effector functions. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 21, 425–456 (2003).

Andrews, A. L. et al. IL-13 receptor α2: a regulator of IL-13 and IL-4 signal transduction in primary human fibroblasts. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 118, 858–865 (2006). This study describes the ability of the non-signalling receptor IL-13Rα2 to regulate not only IL-13- but also IL-4-mediated effects and reveals a new role for IL-13Rα2 as a negative regulator of both IL-13 and IL-4 signalling in human bronchial fibroblasts. IL-13Rα2, by efficiently suppressing T H 2-cell-mediated responses, is a potential therapeutic target for the treatment of asthma.

Grunig, G. et al. Requirement for IL-13 independently of IL-4 in experimental asthma. Science 282, 2261–2263 (1998).