Key Points

-

Cardiogenic shock is characterized by acute hypoperfusion and end-organ dysfunction owing to reduced cardiac output, and is commonly caused by acute myocardial infarction (AMI) with left ventricular dysfunction

-

Emergent revascularization is the only therapy that has been shown to reduce mortality in patients with cardiogenic shock complicating AMI

-

Refractory cardiogenic shock can be defined as ongoing evidence of tissue hypoperfusion despite administration of adequate doses of two vasoactive medications and treatment of the underlying aetiology

-

Refractory cardiogenic shock carries a poor prognosis, with an inhospital mortality of ∼50% despite pharmacological and mechanical circulatory support

-

The use of mechanical circulatory support devices for cardiogenic shock is increasing, but there is currently no evidence showing that they improve clinical outcomes

-

Novel therapeutics and robust randomized trial data are needed to address the persistently high mortality in patients with refractory cardiogenic shock

Abstract

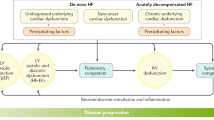

Cardiogenic shock is a life-threatening condition that occurs in response to reduced cardiac output in the presence of adequate intravascular volume and results in tissue hypoxia. Cardiogenic shock has several underlying aetiologies, with the most common being acute myocardial infarction (AMI). Refractory cardiogenic shock presents as persistent tissue hypoperfusion despite administration of adequate doses of two vasoactive medications and treatment of the underlying aetiology. Investigators of the SHOCK trial reported a long-term mortality benefit of emergency revascularization for shock complicating AMI. Since the publication of the SHOCK trial and subsequent guideline recommendations, the increase in community-based use of percutaneous coronary intervention for this condition has resulted in a significant decline in mortality. Despite these successes in the past 15 years, mortality still remains exceptionally high, particularly in patients with refractory cardiogenic shock. In this Review, we discuss the aetiology and pathophysiology of cardiogenic shock and summarize the data on the available therapeutics and their limitations. Although new mechanical circulatory support devices have been shown to improve haemodynamic variables in patients with shock complicating AMI, they did not improve clinical outcomes and are associated with high costs and complications.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$209.00 per year

only $17.42 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Hasdai, D. Cardiogenic shock: diagnosis and treatment (Humana Press, 2002).

De Luca, L. et al. Temporal trends in the epidemiology, management, and outcome of patients with cardiogenic shock complicating acute coronary syndromes. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 17, 1124–1132 (2015).

Dzavik, V. et al. Effects of nitric oxide synthase inhibition on hemodynamics and outcome of patients with persistent cardiogenic shock complicating acute myocardial infarction: a phase II dose-ranging study. Eur. Heart J. 28, 1109–1116 (2007).

Kohsaka, S. et al. Systemic inflammatory response syndrome after acute myocardial infarction complicated by cardiogenic shock. Arch. Intern. Med. 165, 1643–1650 (2005).

Hochman, J. S. et al. Cardiogenic shock complicating acute myocardial infarction — etiologies, management, and outcome: a report from the SHOCK trial registry. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 36, 1063–1070 (2000).

Hochman, J. S. et al. Early revascularization in acute myocardial infarction complicated by cardiogenic shock. N. Engl. J. Med. 341, 625–634 (1999).

Holmes, D. R. et al. GUSTO-I Investigators. Contemporary reperfusion therapy for cardiogenic shock: the Gusto-I trial experience. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 26, 668–674 (1995).

Thiele, H. et al. Intra-aortic balloon support for myocardial infarction with cardiogenic shock. N. Engl. J. Med. 367, 1287–1296 (2012).

Kar, B., Gregoric, I. D., Basra, S. S., Idelchik, G. M. & Loyalka, P. The percutaneous ventricular assist device in severe refractory cardiogenic shock. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 57, 688–696 (2011).

Laslett, L. J. et al. The worldwide environment of cardiovascular disease: prevalence, diagnosis, therapy and policy issues. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 60, S1–S49 (2012).

Babaev, A. et al. Trends in management and outcomes of patients with acute myocardial infarction complicated by cardiogenic shock. JAMA 294, 448–454 (2005).

Webb, J. G. et al. Implications of the timing of onset of cardiogenic shock after acute myocardial infarction: a report from the SHOCK trial registry. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 36, 1084–1090 (2000).

Magnani, J. W. & Dec, G. W. Myocarditis: current trends in diagnosis and treatment. Circulation 116, 876–890 (2006).

Dec, G. W. et al. Viral myocarditis mimicking acute myocardial infarction. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 20, 85–89 (1992).

Felker, G. M. et al. Echocardiographic findings in fulminant and acute myocarditis. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 36, 227–232 (2000).

Angelini, A. et al. Myocarditis mimicking acute myocardial infarction: role of endomyocardial biopsy in the differential diagnosis. Heart 84, 245–250 (2000).

Hasumann, H. et al. Prognosis after implantation of an intra-aortic balloon pump in cardiac surgery calculated with a new score. Circulation 106, 203–206 (2002).

Torchiana, D. F. et al. Intra-aortic balloon pumping for cardiac support: trends in practice and outcome, 1968 to 1995. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 113, 758–764 (1997).

Goldstein, D. J. & Oz, M. C. Mechanical support for postcardiotomy cardiogenic shock. Semin. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 12, 220–228 (2000).

Rao, V. et al. Surgery for acquired heart disease: predictors of low cardiac output syndrome after coronary artery bypass. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 112, 38–51 (1996).

Alsoufi, B., Rao, V., Tang, A., Maganti, M. & Cusimano, R. Risk modeling for ventricular assist device support in post-cardiotomy shock. J. Saudi Heart Assoc. 24, 69–72 (2012).

Mohite, P. N. et al. Short-term ventricular assist device in post-cardiotomy cardiogenic shock: factors influencing survival. J. Artif. Organs. 17, 228–235 (2014).

Jacobs, A. K. et al. Cardiogenic shock caused by right ventricular infarction: a report from the SHOCK registry. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 41, 1273–1279 (2003).

Zehender, M. et al. Right ventricular infarction as an independent predictor of prognosis after acute inferior myocardial infarction. N. Engl. J. Med. 328, 981–988 (1993).

Bowers, T. R. et al. Effect of reperfusion on biventricular function and survival after right ventricular infarction. N. Engl. J. Med. 338, 933–940 (1998).

Bowers, T. R. et al. Patterns of coronary compromise resulting in acute right ventricular ischemic dysfunction. Circulation 106, 1104–1109 (2002).

Dell'Italia, L. J. et al. Hemodynamically important right ventricular infarction: follow up evaluation of right ventricular systolic function at rest and during exercise with radionuclide ventriculography and respiratory gas exchange. Circulation 75, 996–1003 (1987).

Page, D. L., Caulifield, J. B., Kaster, J. A., DeSanctis, R. W. & Sanders, C. A. Myocardial changes associated with cardiogenic shock. N. Engl. J. Med. 285, 133–137 (1971).

Hollenberg, S. M., Kavinsky, C. J. & Parrillo, J. E. Cardiogenic shock. Ann. Intern. Med. 131, 47–59 (1999).

Neumann, F. J. et al. Cardiac release of cytokines and inflammatory response in acute myocardial infarction. Circulation 92, 748–755 (1995).

Nicholls, S. J. et al. Metabolic profiling of arginine and nitric oxide pathways predicts hemodynamic abnormalities and mortality in patients with cardiogenic shock after acute myocardial infarction. Circulation 116, 2315–2324 (2007).

Ratshin, R. A., Rackley, C. E. & Russel, R. O. Hemodynamic evaluation of left ventricular function in shock complicating myocardial infarction. Circulation 45, 127–139 (1972).

Hochman, J. S. & Ohman, E. M. Cardiogenic shock (AHA Clinical Series, 2009).

Reynolds, H. R. et al. Restrictive physiology in cardiogenic shock: observations from echocardiography. Am. Heart J. 151, 890.e9–890.e15 (2006).

Menon, V. et al. The clinical profile of patients with suspected cardiogenic shock due to predominant left ventricular failure: a report form the SHOCK trial registry. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 36, 1071–1076 (2000).

O'Gara, P. T. et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association task force on practice guidelines. Circulation 127, 362–425 (2013).

Jeger, R. V. et al. Causes of death and re-hospitalization in cardiogenic shock. Acute Card. Care 9, 25–33 (2007).

Sleeper, L. A. et al. A severity scoring system for risk assessment of patients with cardiogenic shock: a report form the SHOCK trial and registry. Am. Heart J. 160, 443–450 (2010).

The TRIUMPH Investigators et al. Effect of tilarginine acetate in patients with acute myocardial infarction and cardiogenic shock: the TRIUMPH randomized controlled trial. JAMA 297, 1657–1666 (2007).

Katz, J. N. et al. Predictors of 30-day mortality in patients with refractory cardiogenic shock following acute myocardial infarction despite a patent infarct artery. Am. Heart J. 158, 680–687 (2009).

Harjola, V. et al. Clinical picture and risk prediction of short-term mortality in cardiogenic shock. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 17, 501–509 (2015).

Kapur, N. K. et al. TCT-196 The recover right trial criteria for right ventricular failure: an analysis of the SHould we emergently revascularize Occluded coronaries for Cardiogenic shock (SHOCK) trial and registry. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 66 (15_S), 66 (2015).

Picard, M. H. et al. Echocardiographic predictors of survival and response to early revascularization in cardiogenic shock. Circulation 107, 279–284 (2003).

Menon, V. et al. Outcome and profile of ventricular septal rupture with cardiogenic shock after myocardial infarction: a report from the shock trial registry. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 36, 1110–1116 (2000).

Goldberg, R. J., Spencer, F. A., Gore, J. M., Lessard, D. & Yarzebski, Y. Thirty-year trends (1975 to 2005) in the magnitude of, management of, and hospital death rates associated with cardiogenic shock in patients with acute myocardial infarction: a population-based perspective. Circulation 119, 1211–1219 (2009).

Killip, T. & Kimball, J. T. Treatment of myocardial infarction in a coronary care unit. A two year experience with 250 patients. Am. J. Cardiol. 20, 457–464 (1967).

Wayangankar, S. A. et al. Temporal trends and outcomes of patients undergoing percutaneous coronary interventions for cardiogenic shock in the setting of acute myocardial infarction: a report from the CathPCI Registry. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 9, 341–351 (2016).

Roffi, M. et al. 2015 ESC guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation: task force for the management of acute coronary syndromes without persistent ST-segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur. Heart J. 37, 267–315 (2016).

Sanborn, T. A. et al. Correlates of one-year survival in patients with cardiogenic shock complicating acute myocardial infarction: angiographic findings from the SHOCK trial. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 42, 1373–1379 (2003).

Hochman, J. S. et al. Early revascularization and long-term survival in cardiogenic shock complicating acute myocardial infarction. JAMA 295, 2511–2515 (2006).

Mylotte, D. et al. Primary percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with acute myocardial infarction, resuscitated cardiac arrest, and cardiogenic shock: the role of primary multivessel revascularization. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 6, 115–125 (2013).

US National Library of Medicine. Clinical-Trials.gov, https://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT01927549 (2015).

De Backer, D. et al. Comparison of dopamine and norepinephrine in the treatment of shock. N. Engl. J. Med. 362, 779–789 (2010).

Rihal, C. S. et al. 2015 SCAI/ACC/HFSA/STS clinical expert consensus statement on the use of percutaneous mechanical circulatory support devices in cardiovascular care (endorsed by the American Heart Association, the Cardiological Society of India, and Sociedad Latino Americana de Cardiologia Intervencion; affirmation of value by the Canadian Association of Interventional Cardiology-Association Canadienne de Cardiologie d'intervention). J. Cardiac Fail. 21, 499–518 (2015).

Scheidt, S. et al. Intra-aortic balloon counterpulsation in cardiogenic shock. Report of a co-operative clinical trial. N. Engl. J. Med. 288, 979–984 (1973).

Agarwal, S., Sud, K., Martin, J. M. & Menon, V. Trends in the use of mechanical circulatory support devices in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 8, 1772–1774 (2015).

Chatterjee, S. & Rosensweig, J. Evaluation of intra-aortic balloon counterpulsation. J. Thorac Cardiovasc. Surg. 61, 405–410 (1971).

Kantrowitz, A. et al. Current status of intraaortic balloon pump and initial clinical experience with aortic patch mechanical auxiliary ventricle. Transplant. Proc. 3, 1459–1471 (1971).

Meyns, B., Stolinski, J., Leunens, V., Verbeken, E. & Flameng, W. Left ventricular support by catheter-mountedaxial flow pump reduces infarct size. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 41, 1087–1095 (2003).

Prondzinsky, R. et al. Hemodynamic effects of intra-aortic balloon counterpulsation in patients with acute myocardial infarction complicated by cardiogenic shock: the prospective randomized IABP Shock Trial. Shock 37, 378–384 (2012).

Sjauw, K. D. et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of intra-aortic balloon pumpo therapy in ST-elevation myocardial infarction: should we change the guidelines? Eur. Heart J. 30, 459–468 (2009).

Ohman, E. M. et al. Thrombolysis and counterpulsation to improve survival in myocardial infarction complicated by hypotension and suspected cardiogenic shock or heart failure: results of the TACTICS trial. J. Thromb. Thrombolysis 19, 33–39 (2005).

Sanborn, T. A. et al. Impact of thrombolysis, intraaortic balloon pump counterpulsation, and their combination in cardiogenic shock complicating acute myocardial infarction: a report from the SHOCK Trial Registry. SHould we emergently revascularize Occluded Coronaries for cardiogenic shocK? J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 36, 1123–1129 (2000).

Romeo, A. et al. The outcome of intra-aortic balloon pump support in acute myocardial infarction complicated by cardiogenic shock according to the type of revascularization: a comprehensive meta-analysis. Am. Heart J. 165, 679 (2013).

Steg, G. P. et al. ESC guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation. Eur. Heart J. 33, 2569–2619 (2012).

Ramanathan, K. et al. Rapid complete reversal of systemic hypoperfusion after intra-aortic balloon pump counterpulsation and survival in cardiogenic shock complicating an acute myocardial infarction. Am. Heart J. 162, 268–275 (2011).

Ostadal, P. et al. Direct comparison of percutaneous circulatory support systems in specific hemodynamic conditions in a porcine model. Circ. Arrhythm. Electrophysiol. 5, 1202–1206 (2012).

Kapur, N. K. et al. Mechanical circulatory support for right ventricular failure. JACC Heart Fail. 1, 127–134 (2013).

Seyfarth, M. et al. A randomized clinical trial to evaluate the safety and efficacy of a percutaneous left ventricular assist device versus intra-aortic balloon pumping for treatment of cardiogenic shock caused by myocardial infarction. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 52, 1584–1588 (2008).

Burkhoff, D., Cohen, H., Brunckhorst, C. & O'Neill, W. W. A randomized multicenter clinical study to evaluate the safety and efficacy of the TandemHeart percutaneous ventricular assist device versus conventional therapy with intraaortic balloon pumping for treatment of cardiogenic shock. Am. Heart J. 152, 469.e1–469.e8 (2006).

Thiele, H. et al. Randomized comparison of intra-aortic balloon support with a percutaneous left ventricular assist device in patients with revascularized acute myocardial infarction complicated by cardiogenic shock. Eur. Heart J. 26, 1276–1283 (2005).

Stretch, R., Sauer, C. M., Yuh, D. D. & Bonde, P. National trends in the utilization of short-term mechanical circulatory support: incidence, outcomes, and cost analysis. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 64, 1407–1415 (2014).

Cheng, J. M. et al. Percutaneous left ventricular assist devices versus intra-aortic balloon pump counterpulsation for treatment of cardiogenic shock: a meta-analysis of controlled trials. Eur. Heart J. 30, 2102–2108 (2009).

Shah, A. P. et al. Clinical and economic effectiveness of percutaneous ventricular assist devices for high-risk patients undergoing coronary intervention. J. Invasive Cardiol. 27, 148–154 (2015).

Cheng, R. et al. Lack of survival benefit found with use of intraaoartic balloon pump in extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: a pooled experience of 1517 patients. J. Invasive Cardiol. 27, 453–458 (2015).

Paden, M. L., Conrad, S. A., Rycus, P. T. & Thiagarajan, R. R. Extracorporeal life support organization registry report 2012. ASAIO J. 59, 202–210 (2013).

Mohite, P. N. et al. Distal limb perfusion: Achilles' heel in peripheral venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Artif. Organs 38, 940–944 (2014).

Takayama, H. et al. Bridge-to-decision therapy with a continuous-flow external ventricular assist device in refractory cardiogenic shock of various causes. Circulation 7, 799–806 (2014).

Takayama, H., Chen, J. M., Jorde, U. P. & Naka, Y. Implantation technique of the CentriMag biventricular assist device allowing ambulatory rehabilitation. Interact. Cardiovasc. Thorac. Surg. 12, 110–111 (2011).

Diez-Villanueva, P. et al. Early treatment of refractory cardiogenic shock with percutaneous veno-arterial ECMO implanted in the cardiac catheterization laboratory. Rev. Esp. Cardiol. (Engl. Ed.) 67, 1059–1061 (2014).

Hsu, P. S. et al. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for refractory cardiogenic shock after cardiac surgery: predictors of early mortality and outcome from 51 adult patients. Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 37, 328–333 (2010).

Takayama, H. et al. Clinical outcome of mechanical circulatory support for refractory cardiogenic shock in the current era. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 32, 106–111 (2013).

Cheung, A., Freed, D., Hunziker, P. & Leprince, P. TCT-371 first clinical evaluation of a novel percutaneous right ventricular assist device: the Impella RP. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 59 (Suppl. 1), E872 (2012).

Atiemo, A. D., Conte, J. V. & Heldman, A. W. Resuscitation and recovery from acute right ventricular failure using a percutaneous right ventricular assist device. Catheter. Cardiovasc. Interv. 66, 78–82 (2006).

Cheung, A. W., White, C. W., Davis, M. K. & Freed, D. H. Short-term mechanical circulatory support for recovery from acute right ventricular failure: clinical outcomes. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 33, 794–799 (2014).

Acharya, D. et al. Ventricular assist device in acute myocardial infarction-findings from INTERMACS. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 34, 4S (2015).

Chen, J. M. et al. Improved survival rates support left ventricular assist device implantation early after myocardial infarction. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 33, 1903–1908 (1999).

Rose, E. A. et al. Long-term use of a left ventricular assist device for end-stage heart failure. N. Engl. J. Med. 345, 1435–1443 (2001).

Slaughter, M. S. et al. Advanced heart failure treated with continuous-flow left ventricular assist device. N. Engl. J. Med. 361, 2241–2251 (2009).

Kirklin, J. K. et al. Seventh INTERMACS annual report: 15,000 patients and counting. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 34, 1495–1504 (2015).

Cotts, W. G. et al. Predictors of hospital length of stay after implantation of a left ventricular assist device: an analysis of the INTERMACS registry. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 33, 682–688 (2014).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors researched data for the article, made substantial contribution to discussion of the content, and wrote, reviewed, and edited the manuscript before submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Reyentovich, A., Barghash, M. & Hochman, J. Management of refractory cardiogenic shock. Nat Rev Cardiol 13, 481–492 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/nrcardio.2016.96

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nrcardio.2016.96

This article is cited by

-

Organ dysfunction, injury, and failure in cardiogenic shock

Journal of Intensive Care (2023)

-

Rescue aortic valvuloplasty for severe aortic stenosis is simple and effective in severely hemodynamically compromised patients presenting to centers without on-site heart surgery or TAVI facilities

Heart and Vessels (2023)

-

Mottling as a prognosis marker in cardiogenic shock

Annals of Intensive Care (2023)

-

Electrocardiographic patterns predict the presence of collateral circulation and in-hospital mortality in acute total left main occlusion

BMC Cardiovascular Disorders (2022)

-

Simulation of Fluid-Structure Interaction in Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation Circulatory Support Systems

Journal of Cardiovascular Translational Research (2022)