Abstract

Memantine, an uncompetitive antagonist of glutamate receptors of the N-methyl-D-aspartate type is approved for the treatment of moderate to severe Alzheimer's disease. A growing body of evidence supports a link between the glutamatergic neurotransmission and schizophrenia. The purpose of this study (MEM-MD-29) was to examine the efficacy and safety of memantine as an adjunctive treatment to atypical antipsychotics in patients with persistent residual psychopathology of schizophrenia. In this double-blind, placebo-controlled study, participants were assigned to receive 20 mg/day memantine (n=70) or placebo (n=68), in addition to continuing treatment with atypical antipsychotics, for 8 weeks. The primary efficacy measure was the total score on the Positive and Negative Symptom Scale (PANSS). Secondary measures were positive and negative PANSS scores, PANSS responders, Calgary Depression Scale for Schizophrenia (CDSS), Clinical Global Impression of Severity (CGI-S), Clinical Global Impression of Improvement (CGI-I), and Brief Assessment of Cognition in Schizophrenia (BACS). Missing data were imputed using the last observation carried forward (LOCF) approach. Safety was assessed by means of physical examination, clinical laboratory evaluation, recording of adverse events (AEs), and measures of extrapyramidal symptoms. At end point, total PANSS scores did not differ between the memantine and the placebo group (p=0.570, LOCF). A similar outcome was observed for all secondary measures. The frequency of serious AEs in the memantine vs placebo group was 8.7 vs 6.0%; treatment discontinuations because of AEs occurred in 11.6 and 3.0% of patients in these groups, respectively. Memantine showed no efficacy as an adjunctive therapy in schizophrenia patients with residual psychopathology and was associated with a higher incidence of AEs than placebo.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

Antipsychotic drugs are the mainstay of treatment for patients with schizophrenia. Despite proven efficacy, their use is associated with a high prevalence of residual morbidity, such as cognitive deficits and the persistence of positive and negative symptoms (Stahl and Grady, 2004). As a consequence, clinicians often treat patients with chronic schizophrenia with multiple medications, including combinations of antipsychotics and anticonvulsants (Zink et al, 2004; Riedel et al, 2005; Tuominen et al, 2006). Unfortunately, the results of clinical trials provide little support for such efforts (Stahl and Grady, 2004; Buckley and Shendarkar, 2005; Chakos et al, 2006; Honer et al, 2006; Kreyenbuhl et al, 2006; Messer et al, 2006). Therefore, there is an urgent need for the development of more effective treatments for schizophrenia for use as monotherapies or as adjuncts to antipsychotic drugs.

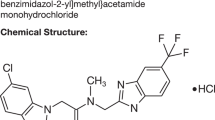

Memantine, an uncompetitive N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonist (Parsons et al, 2007), is approved for the treatment of moderate to severe Alzheimer's disease (AD) in many countries worldwide, including the United States and countries of the European Union. It has been shown to delay cognitive decline in patients with dementia (Reisberg et al, 2003; Tariot et al, 2004; McShane et al, 2006), an effect hypothesized to arise from its ability to block the excessive influx of calcium ions through the channel of the activated NMDA receptor (Parsons et al, 2007).

The rationale for using memantine as an adjunctive therapy for patients with schizophrenia comes from the fact that the glutamatergic system, and specifically hypofunctioning of NMDA receptors, has been implicated in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia, and is thought to mediate several psychopathological components of the disease including psychotic, negative, and cognitive symptoms (Javitt and Zukin, 1991; Bressan and Pilowsky, 2000; Carlsson et al, 2000; Egerton et al, 2005; Yang and Chen, 2005).

Consequently, the glutamate system and NMDA receptors have been an attractive target for drug development. Several clinical trials have shown improvement in patients with schizophrenia receiving atypical antipsychotics when treated with NMDA receptor allosteric agonists at the glycineB site (glycine, D-serine, D-cycloserine, sarcosine; Coyle et al, 2002; Tsai and Coyle, 2002; Heresco-Levy et al, 2005; Lane et al, 2005; Buchanan et al, 2007). Paradoxically, schizophrenic symptoms may also be improved by NMDA receptor antagonists, as glutamatergic neurons in the prefrontal cortex are inhibited by NMDA-mediated GABA interneurons (Maccaferri and Dingledine, 2002; Homayoun and Moghaddam, 2007). NMDA receptor antagonists have been shown to release this inhibition, producing profound indirect excitation of cortical pyramidal neurons and increased glutamatergic outflow in the cortex (Moghaddam et al, 1997; Homayoun and Moghaddam, 2007). Finally, the efficacy of memantine in delaying cognitive decline of patients with AD (Reisberg et al, 2003; Tariot et al, 2004; McShane et al, 2006) suggests a potential for treating cognitive impairment, as well as for preventing progression of the illness in schizophrenia.

The purpose of this study was to examine the efficacy and safety of memantine as an addition to ongoing therapy with atypical antipsychotics in patients with schizophrenia who were partially responsive to antipsychotic treatment but exhibited persistent residual psychopathology.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants

Participants were male or female outpatients, 18–65 years at the time of screening, with a diagnosis of schizophrenia (paranoid, disorganized, catatonic, or undifferentiated type) or schizoaffective disorder, based on the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID) (APA, 2000), for at least 2 years. Patients exhibited residual positive symptoms at both the screening and baseline (total score ⩾26 on the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS), and score ⩾4 on at least one of the BPRS psychosis factor items: conceptual disorganization, hallucinatory behavior, suspiciousness, and unusual thought content). They were also required to have residual positive symptoms for at least 3 months immediately preceding the trial, with no exacerbation in the last 4 weeks. Patients had been treated with atypical antipsychotic monotherapy (olanzapine, risperidone, quetiapine, aripiprazole, or ziprasidone) for at least 3 months before randomization, and were required to remain on a stable dose for at least 4 weeks before randomization and throughout the study. Mood stabilizers (lithium and divalproex) and antidepressants (only the selective serotonine reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) venlafaxine, and mirtazapine) were permitted as part of antipsychotic pharmacotherapy, with doses kept constant throughout the period of randomized treatment. Women practiced a medically acceptable method of contraception, or were surgically sterile or post-menopausal for at least 2 years. Women of childbearing potential were required to have a negative pregnancy test at the screening. All patients were also required to speak, read, and understand English, and provide verbal assent.

Criteria for exclusion were a 20% change in total BPRS score from screening to baseline; primary or secondary diagnosis of bipolar I disorder, either manic or mixed episode, as defined by DSM-IV (SCID); active suicide or homicide intent, or a suicide or homicide attempt in the preceding 6 months; organic brain disease, dementia, or a traumatic brain injury; evidence or history of malignancy (other than excised basal-cell carcinoma) or any significant hematological, endocrine, cardiovascular, respiratory, renal, hepatic, or gastrointestinal disease; or abnormalities on physical examination, vital signs, electrocardiogram (ECG), or clinical laboratory values, unless judged to be clinically insignificant by the study physician.

Additional exclusion criteria were a history of substance dependence (including alcohol, but excluding nicotine) as defined by DSM-IV and relapse within the past 6 months, or substance abuse within the 3 months preceding the trial; positive urine test for illicit drugs; HIV infection; use of a disallowed concomitant medication (including anesthetics, anticonvulsants (other than divalproex), anti-Parkinson's drugs, cholinesterase inhibitors, herbal supplements, muscle relaxants, systemic steroids, and stimulants); previous participation in an investigational study of memantine or neramexane; treatment with any investigational drug within 30 days or five half lives (whichever is longer) before study entry; or a history of hypersensitivity to memantine or other drugs of the same class.

Patients could also be excluded from the trial if judged unsuitable by the investigator.

After complete description of the study to the subjects, written informed consent was provided by patient, guardian, or legally authorized representative.

Study Design

This proof-of-concept study was a multicenter, 8-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized trial. Eligible patients were assigned to receive placebo or memantine (once daily), with dosing titration as follows: week 1, 5 mg/day; week 2, 10 mg/day; weeks 3–8, 20 mg/day. The study profile is shown in Figure 1. The required sample size was determined using the assumption that a clinically meaningful difference between the two treatment groups would be 8.5 points in total PANSS score with a pooled standard deviation of 14.7.

Efficacy

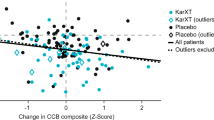

The primary outcome measure was the total score on the Positive and Negative Symptoms Scale (PANSS; Kay et al, 1987), administered at baseline (week 0) and at all subsequent visits (weeks 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, and 8). Secondary outcome measures included positive and negative PANSS scores (all visits), PANSS responders (defined as patients with a 10% or greater reduction in total PANSS score), Calgary Depression Scale for Schizophrenia (CDSS; weeks 0 and 8; Addington et al, 1996), Clinical Global Impression of Severity (CGI-S; weeks 0, 4, 6, and 8; Guy, 1976), Clinical Global Impression of Improvement (CGI-I; weeks 4, 6, and 8), and composite z-scores and total construct scores of Brief Assessment of Cognition in Schizophrenia (BACS; weeks 0, 4, and 8; Keefe et al, 2004; Keefe et al, 2006). Change from baseline by visit in PANSS hostility factor score was an additional efficacy measure.

The PANSS is a 30-item scale, developed to assess both the positive and the negative syndromes of patients with schizophrenia. The PANSS total score is rated based on a structured clinical interview with the patient (conducted by an experienced clinician or other trained psychiatric rater) and on supporting clinical information, obtained from family, hospital staff, or other reliable informants. Each item is scored on a continuous 7-point scale, and provides evaluation of positive and negative symptoms, as well as general psychopathology. Positive and negative PANSS scores are 7-item, 7-point severity scales derived from the PANSS total (Kay et al, 1987). The PANSS hostility factor (Bell et al, 1994) is the sum of six PANSS items that measure excitement (item P4), grandiosity (P5), suspiciousness (P6), hostility (P7), uncooperativeness (G8), and poor impulse control (G14). PANSS hostility factor was selected with the purpose of investigating whether memantine treatment confers benefits on symptoms of hostility and agitation/excitement. The CDSS is a 9-item scale designed to assess depression specifically in patients with schizophrenia (Addington et al, 1996). The 7-point CGI-S scale measures the overall severity of illness, compared to the severity of other patients the physician has observed, whereas the 7-point CGI-I measures the change from baseline in the overall severity for each individual patient (Guy, 1976). BACS is a 7-item instrument, designed to measure treatment-related improvements in cognition of patients with schizophrenia (Keefe et al, 2004; Keefe et al, 2006). It has been validated in patients with schizophrenia and shown to correlate well with both real-world functional outcomes and composite scores from more extensive batteries (Keefe et al, 2006; Kraus and Keefe, 2007). In PANSS, CGI-I, and CGI-S, higher scores are associated with greater impairment. In BACS, lower score signifies greater impairment. A higher CDSS score indicates higher likelihood of depression in patients with schizophrenia.

The trial was conducted in established clinical centers, experienced in this type of research. All assessment tools were administered by experienced clinicians or other trained raters. In addition, rater reliability training was conducted at the investigator meetings before the start of the study. Finally, a post hoc analysis of possible side effects was performed, and yielded no significant side effects.

Statistical Analysis

All efficacy analyses were performed based on the intent-to-treat population, which included all patients in the safety population who had at least one post-baseline PANSS assessment. Hypothesis testing and confidence intervals were two-sided, at the 5% significance level.

The primary efficacy parameter was the change from baseline to week 8 in PANSS total score. It was analyzed using a two-way analysis of covariance model, with treatment group and study center as factors, and the baseline PANSS total score as the covariate. The normality assumption for the primary efficacy parameter was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test. The secondary efficacy parameters, CGI-S and CGI-I, were analyzed using the Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel (CMH) test with modified ridit scores, controlling for study center. All efficacy measures were analyzed as specified in the study protocol, using the last observation carried forward (LOCF) approach for imputation of missing values; the observed cases (OCs) approach was used for supportive analyses. The PANSS responder analysis was performed using the logistic regression model, with treatment group and baseline PANSS total score as explanatory variables.

Safety and Tolerability

Safety assessments included recording of adverse events (AEs) and concomitant medications, physical examination, monitoring of extrapyramidal symptoms (using the Barnes Akathisia Scale, Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale, and Simpson–Angus Scale), vital sign measurements (systolic and diastolic blood pressure, pulse rate, and body weight), ECG, and laboratory tests (including thyroid function and pregnancy tests). A urine drug screen was also performed at screening. Patients were seen by a physician at each visit and the evaluation was documented.

RESULTS

Baseline Characteristics

Treatment groups were well matched at baseline (Table 1), except for gender (placebo, 79. 1% male; memantine, 59.4% male) and the use of non-SSRI antidepressants (placebo, 13.4%; memantine, 34.8%). Baseline measures of psychopathology and cognition confirmed the presence of substantial residual psychopathology in the participants.

Efficacy

The group treated with memantine experienced a mean change (±SD) from baseline to week 8 in total PANSS score (primary outcome measure) of −4.5±10.9, whereas the placebo-treated group experienced a mean change of −3.7±10.2. The least squares mean difference between the two groups was not statistically significant (LOCF, p=0.570; OC, p=0.328).

The change from baseline to week 8 observed on all scored secondary outcomes was also not significant between memantine and placebo groups (Table 2, LOCF; OC data not shown). The percentage of PANSS responders at week 8 did not significantly differ between the memantine and the placebo group (39.1 vs 31.8%, respectively; p=0.378).

Safety and Tolerability

There were no deaths in this study. The number of patients who reported serious AEs (SAEs), treatment-emergent AEs, or who discontinued the study because of AEs are summarized in Table 3; discontinuations because of AEs were higher in the memantine group than in the placebo group (11.6 vs 3.0%). The most frequent SAE reported in the memantine group was an exacerbation of schizophrenia symptoms (2.9%), but it was less frequent compared to the placebo group (6.0%). No other SAE was experienced by more than one patient in either group. The most frequent treatment-emergent AEs in the memantine group were headache, insomnia, constipation, fatigue, and dizziness (Table 3). Dizziness (8.7 vs 3.0%) and auditory hallucinations (5.8 vs 0%) occurred in at least 5% of the memantine-treated patients and with an incidence at least twice that of the placebo group. Most AEs (88.3% in the memantine and 92.4% in the placebo group) were considered to be mild or moderate in severity; 56.7 and 45.5% of AEs experienced in the memantine and placebo groups, respectively, were judged to be related or possibly related to study medication. However, the increases in auditory hallucinations in patients were thought not to be related to study medication.

Review of vital signs, laboratory, ECG, and extrapyramidal parameters revealed clinically unremarkable changes from baseline and a low incidence of potentially clinically significant events.

DISCUSSION

In this proof-of-concept study, there was no evidence of therapeutic benefits associated with adjunctive memantine treatment of residual psychopathology in patients with schizophrenia maintained on atypical antipsychotics. Moreover, the presence of auditory hallucinations as a treatment-emergent AE, despite being judged by clinicians to not be related to study medicine, suggests the possibility of worsening of psychotic symptoms by memantine. In addition, memantine treatment was associated with an increased incidence of miscellaneous side effects.

Memantine has been shown to be effective compared to placebo in delaying cognitive decline in patients with dementia (Winblad and Poritis, 1999; Reisberg et al, 2003; Tariot et al, 2004; Peskind et al, 2006), but not superior to placebo for enhancing cognition in healthy subjects (Rammsayer, 2001). The lack of efficacy and increased side effects of memantine treatment in this study suggest that adjunctive memantine does not provide therapeutic benefit for patients with residual schizophrenia symptoms. It is possible, however remotely, that the participants in this study (patients with chronic schizophrenia, with mild to moderate residual positive and negative symptoms) may not have been the optimal population for studying the effects of memantine. Although no effects on positive and negative schizophrenia symptoms were shown in this trial, it is possible that memantine may be helpful for patients with severe residual psychopathology or more pronounced cognitive impairment. The results of a recent 12-week, open-label trial of memantine involving 18 cognitively impaired patients with schizophrenia demonstrated that memantine treatment (20 mg/day) improved average positive and negative PANSS score by 4.2 and 6.5 points, respectively, as well as the performance on the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale–III (Waheed et al, 2006). In our study, mean (SE) baseline composite BACS z-scores of 0.01 (0.09) and 0.19 (0.09) for the placebo and memantine group, respectively, indicate a study population with only mild to moderate cognitive impairment (Keefe et al, 2004), which may reflect the relatively young age of the participants (Kurtz, 2005).

Other factors that may have influenced the outcome of this trial include (1) the variety of atypical antipsychotics used (Table 1), as the study was not sufficiently powered to detect their individual interactions with memantine, (2) the relatively short duration of the trial (8 weeks), (3) the relatively long titration period (3 weeks), which allowed exposure to a maximum daily dose of memantine for only 62.5% time of the trial (5 weeks), and (4) the dose of memantine that was used.

The safety profile of memantine from this trial was less favorable than the established safety profiles of memantine from dementia trials (McShane et al, 2006), and from a pilot trial in major depressive disorder (Ferguson and Shingleton, 2007). Also, the outcome of a recent trial in safety and tolerability of memantine (Jones et al, 2007) suggests that a less favorable AE profile of the memantine group in our study was not a consequence of once-daily (vs the standard, twice-daily) dosing regimen. The occurrence of auditory hallucinations in the memantine group (5.8%), but not in the placebo group may be of particular importance for patients with schizophrenia, and may reflect a worsening in the hypofunction of NMDA receptors and dysregulated glutamatergic neurotransmission (Deakin and Simpson, 1997; Krystal et al, 2000). This was not entirely surprising, as the glutamate (NMDA receptor hypofunction) hypothesis of schizophrenia would predict that patients' symptoms would either improve or worsen, depending on whether the glutamatergic imbalance in schizophrenia involves a deficit or excess of glutamate release and synaptic neurotransmission. The positive results of the recent study with LY2140023, a selective agonist of metabotropic glutamate receptor types 2 and 3, which is believed to act by reducing the presynaptic release of glutamate (Patil et al, 2007), suggests that the schizophrenia imbalance is in the direction of excessive glutamate release.

It should be noted that recent large, multicenter trials failed to demonstrate any beneficial effects of glycine or D-cycloserine (glycine-site agonists of NMDA receptors) on negative symptoms or cognition (Carpenter et al, 2005; Buchanan et al, 2007) or of lamotrigine (an inhibitor of glutamate release) on total PANSS score (Goff et al, 2006). However, the widely used mood stabilizer valproate (divalproex) was found to enhance the rate (if not the degree) of improvement in symptoms when added to antipsychotic medication in acutely exacerbated patients with schizophrenia (Casey et al, 2003).

This study is important for several reasons. First, there is a desperate need for the development of new schizophrenia treatments with innovative mechanisms of action. All currently available drugs for mono- or adjunctive therapy of schizophrenia bind to the dopamine D2 receptor, and a trial of an uncompetitive NMDA receptor antagonist with the prospect of neuroprotection was a potentially important new strategy. Second, despite the widespread practice of combining medications, very few studies have directly assessed the efficacy of adjunctive treatments as was done in this study. Finally, it is essential to report promptly the results of all clinical trials (including negative findings), particularly those in which novel treatment approaches are tested.

References

Addington D, Addington J, Atkinson M (1996). A psychometric comparison of the Calgary Depression Scale for Schizophrenia and the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale. Schizophr Res 19: 205–212.

APA (2000). DSM-IV-TR: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. American Psychiatric Press: Washington, DC.

Bell MD, Lysaker PH, Milstein RM, Beam-Goulet JL (1994). Concurrent validity of the cognitive component of schizophrenia: relationship of PANSS scores to neuropsychological assessments. Psychiatry Res 54: 51–58.

Bressan RA, Pilowsky LS (2000). Imaging the glutamatergic system in vivo—relevance to schizophrenia. Eur J Nucl Med 27: 1723–1731.

Buchanan RW, Javitt DC, Marder SR, Schooler NR, Gold JM, McMahon RP et al (2007). The Cognitive and Negative Symptoms in Schizophrenia Trial (CONSIST): the efficacy of glutamatergic agents for negative symptoms and cognitive impairments. Am J Psychiatry 164: 1593–1602.

Buckley PF, Shendarkar N (2005). Treatment-refractory schizophrenia. Curr Opin Psychiatry 18: 165–173.

Carlsson A, Waters N, Waters S, Carlsson ML (2000). Network interactions in schizophrenia—therapeutic implications. Brain Res Brain Res Rev 31: 342–349.

Carpenter WT, Buchanan RW, Javitt DC, Marder SR, Schooler NR, Heresco-Levy U et al (2005). Testing two efficacy hypotheses for the treatment of negative symptoms. Schizophr Bull 20th International Congress on Schizophrenia Research, Savannah, GA.

Casey DE, Daniel DG, Wassef AA, Tracy KA, Wozniak P, Sommerville KW (2003). Effect of divalproex combined with olanzapine or risperidone in patients with an acute exacerbation of schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology 28: 182–192.

Chakos MH, Glick ID, Miller AL, Hamner MB, Miller del D, Patel JK et al (2006). Baseline use of concomitant psychotropic medications to treat schizophrenia in the CATIE trial. Psychiatr Serv 57: 1094–1101.

Coyle JT, Tsai G, Goff DC (2002). Ionotropic glutamate receptors as therapeutic targets in schizophrenia. Curr Drug Targets CNS Neurol Disord 1: 183–189.

Deakin JF, Simpson MD (1997). A two-process theory of schizophrenia: evidence from studies in post-mortem brain. J Psychiatr Res 31: 277–295.

Egerton A, Reid L, McKerchar CE, Morris BJ, Pratt JA (2005). Impairment in perceptual attentional set-shifting following PCP administration: a rodent model of set-shifting deficits in schizophrenia. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 179: 77–84.

Ferguson JM, Shingleton RN (2007). An open-label, flexible-dose study of memantine in major depressive disorder. Clin Neuropharmacol 30: 136–144.

Goff DC, Keefe RS, Volavka J, Krystal JH, Davy K, Thompson TR et al (2006). Lamotrigine added to atypical antipsychotics for treatment of schizophrenia: results of two double-blind randomized clinical trials. Am Psychiatr Assoc 159th Annual Meeting, Toronto, ON.

Guy W (1976). ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology. In: Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office, U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare Publication No. 76-338: Washington, DC.

Heresco-Levy U, Javitt DC, Ebstein R, Vass A, Lichtenberg P, Bar G et al (2005). D-Serine efficacy as add-on pharmacotherapy to risperidone and olanzapine for treatment-refractory schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry 57: 577–585.

Homayoun H, Moghaddam B (2007). NMDA receptor hypofunction produces opposite effects on prefrontal cortex interneurons and pyramidal neurons. J Neurosci 27: 11496–11500.

Honer WG, Thornton AE, Chen EY, Chan RC, Wong JO, Bergmann A et al (2006). Clozapine alone versus clozapine and risperidone with refractory schizophrenia. N Engl J Med 354: 472–482.

Javitt DC, Zukin SR (1991). Recent advances in the phencyclidine model of schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 148: 1301–1308.

Jones RW, Bayer A, Inglis F, Barker A, Phul R (2007). Safety and tolerability of once-daily versus twice-daily memantine: a randomised, double-blind study in moderate to severe Alzheimer's disease. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 22: 258–262.

Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA (1987). The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 13: 261–276.

Keefe RS, Goldberg TE, Harvey PD, Gold JM, Poe MP, Coughenour L (2004). The Brief Assessment of Cognition in Schizophrenia: reliability, sensitivity, and comparison with a standard neurocognitive battery. Schizophr Res 68: 283–297.

Keefe RS, Poe M, Walker TM, Harvey PD (2006). The relationship of the Brief Assessment of Cognition in Schizophrenia (BACS) to functional capacity and real-world functional outcome. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol 28: 260–269.

Kraus MS, Keefe RS (2007). Cognition as an outcome measure in schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry Suppl 50: s46–s51.

Kreyenbuhl J, Valenstein M, McCarthy JF, Ganoczy D, Blow FC (2006). Long-term combination antipsychotic treatment in VA patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 84: 90–99.

Krystal JH, Belger A, Abi-Saab W, Moghaddam B, Charney DS, Anand A et al (2000). Glutamatergic contributions to cogntive disfunction in schizophrenia. In: Harvey PD, Sharma T (eds). Cognition in Schizophrenia: Impairments, Importance and Treatment Strategies. Oxford University Press: London. pp 126–155.

Kurtz MM (2005). Neurocognitive impairment across the lifespan in schizophrenia: an update. Schizophr Res 74: 15–26.

Lane HY, Chang YC, Liu YC, Chiu CC, Tsai GE (2005). Sarcosine or D-serine add-on treatment for acute exacerbation of schizophrenia: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 62: 1196–1204.

Maccaferri G, Dingledine R (2002). Control of feedforward dendritic inhibition by NMDA receptor-dependent spike timing in hippocampal interneurons. J Neurosci 22: 5462–5472.

McShane R, Areosa Sastre A, Minakaran N (2006). Memantine for dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev: CD003154.

Messer T, Tiltscher C, Schmauss M (2006). [Polypharmacy in the treatment of schizophrenia]. Fortschr Neurol Psychiatr 74: 377–391.

Moghaddam B, Adams B, Verma A, Daly D (1997). Activation of glutamatergic neurotransmission by ketamine: a novel step in the pathway from NMDA receptor blockade to dopaminergic and cognitive disruptions associated with the prefrontal cortex. J Neurosci 17: 2921–2927.

Parsons CG, Stoffler A, Danysz W (2007). Memantine: a NMDA receptor antagonist that improves memory by restoration of homeostasis in the glutamatergic system—too little activation is bad, too much is even worse. Neuropharmacology 53: 699–723.

Patil ST, Zhang L, Martenyi F, Lowe SL, Jackson KA, Andreev BV et al (2007). Activation of mGlu2/3 receptors as a new approach to treat schizophrenia: a randomized Phase 2 clinical trial. Nat Med 13: 1102–1107.

Peskind ER, Potkin SG, Pomara N, Ott BR, Graham SM, Olin JT et al (2006). Memantine treatment in mild to moderate Alzheimer disease: A 24-week, randomized, controlled trial. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 14: 704–715.

Rammsayer TH (2001). Effects of pharmacologically induced changes in NMDA-receptor activity on long-term memory in humans. Learn Mem 8: 20–25.

Reisberg B, Doody R, Stoffler A, Schmitt F, Ferris S, Mobius HJ (2003). Memantine in moderate-to-severe Alzheimer's disease. N Engl J Med 348: 1333–1341.

Riedel M, Strassnig M, Schwarz MJ, Muller N (2005). COX-2 inhibitors as adjunctive therapy in schizophrenia: rationale for use and evidence to date. CNS Drugs 19: 805–819.

Stahl SM, Grady MM (2004). A critical review of atypical antipsychotic utilization: comparing monotherapy with polypharmacy and augmentation. Curr Med Chem 11: 313–327.

Tariot PN, Farlow MR, Grossberg GT, Graham SM, McDonald S, Gergel I (2004). Memantine treatment in patients with moderate to severe Alzheimer disease already receiving donepezil: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 291: 317–324.

Tsai G, Coyle JT (2002). Glutamatergic mechanisms in schizophrenia. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 42: 165–179.

Tuominen H, Tiihonen J, Wahlbeck K (2006). Glutamatergic drugs for schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev: CD003730.

Waheed W, Hussain MZ, Hussain S (2006). Memantine in the treatment of schizophrenic cognitive impairment. Am Psychiatr Assoc 159th Annual Meeting, Toronto, Canada.

Winblad B, Poritis N (1999). Memantine in severe dementia: results of the 9M-Best Study (Benefit and efficacy in severely demented patients during treatment with memantine). Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 14: 135–146.

Yang CR, Chen L (2005). Targeting prefrontal cortical dopamine D1 and N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor interactions in schizophrenia treatment. Neuroscientist 11: 452–470.

Zink M, Henn FA, Thome J (2004). Combination of amisulpride and olanzapine in treatment-resistant schizophrenic psychoses. Eur Psychiatry 19: 56–58.

Acknowledgements

Forest Laboratories Inc. provided funding and statistical support for this study. We acknowledge Vojislav Pejovic, PhD and Michael L. Miller, PhD from Prescott Medical Communications Group for medical writing and editorial support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Additional information

Previous presentation: None.

Location of work: This trial has been conducted in the following US sites: Dartmouth Hitchcock Medical Center, Department of Psychiatry, Lebanon, NH; Metropolitan Psychiatric Center, St Louis, MO; VA San Diego Healthcare System, San Diego, CA; Duke University, John Umstead Hospital, Butner, NC; Medication Research Clinic, San Antonio, TX; University of Iowa, Psychiatric Research, Iowa City, IA; University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, OH; UNC Chapel Hill, Clinical Research Unit, Raleigh, NC; University of Miami, Jackson Memorial Hospital, Mental Health Hospital Center, Miami, FL; Nathan Kline Institute, Psychiatric Research Department, Orangeburg, NY; Synergy Clinical Research, National City, CA; University Hills Clinical Research, Irving, TX; CBH Health, LLC, Rockville, MD.

Members of the MEM-MD-29 study group included

Alan Green, MD, Dartmouth Hitchcock Medical School, Lebanon, NH; John Csernansky, MD, Metropolitan Psychiatric Center, St. Louis, MO; Hua Jin, MD, VA San Diego Healthcare System, San Diego, CA; Joseph McEvoy, MD, Duke University, John Umstead Hospital, Butner, NC; Alexander Miller, MD, Medication Research Clinic, San Antonio, TX; Del Miller, MD, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA; Henry Nasrallah, MD, MA, University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, OH; Olgierd Pucilowski, MD, PhD, University of North Carolina—Chapel Hill, Raleigh, NC; Richard Steinbook, MD, University of Miami, Jackson Memorial Hospital, Miami, FL; Jan Volavka, MD, Nathan Kline Institute, Orangeburg, NY; Mohammed A. Bari, MD, Synergy Clinical Research, National City, CA; Mary Ann Knesevich, MD, University Hills Clinical Research, Irving, TX; Robert E. Litman, MD, CBH Health, LLC, Rockville, MD.

DISCLOSURE/CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Jeffrey Lieberman serves as a consultant and/or advisor for Astra Zeneca, Eli Lilly, Forest Laboratories, GlaxoSmithKline, Pfizer and Wyeth; and as a member of the Data Safety Management Board (DSMB) for Solvay and Wyeth. He does not receive financial compensation or salary support for his participation as a consultant or as a member of a board. He receives grant support from AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Merck, Pfizer and Wyeth; and he holds a patent from Repligen.

Allyson Gage, Kelly Papadakis, and Xinwei Daniel Jia are employees of Forest Laboratories Inc.

John Csernansky has received research grants from the NIMH, NIA, and the Schizophrenia Trials Network (University of North Carolina). In addition, he has been a consultant for Sanofi-Aventis, Eli Lilly, Solvay, and Wyeth Pharmaceuticals, and has received honoraria for lectures from Eli Lilly and Janssen Pharmaceuticals.

Robert Litman has been a consultant for Dainippon-Sumitomo, and an Independent Contractor (Principal Investigator) for clinical trial contracts through CBH Health, LLC, with the following sponsors: AstraZeneca, Sanofi-Aventis, Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceutical Research and Development LLC, Forest Research Institute, Wyeth, Vanda Pharmaceuticals, Mutual Pharmaceuticals.

Jan Volavka has received travel funds from Eli Lilly & Company.

This study was designed, financed, and analyzed by Forest Laboratories Inc.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lieberman, J., Papadakis, K., Csernansky, J. et al. A Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Study of Memantine as Adjunctive Treatment in Patients with Schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacol 34, 1322–1329 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1038/npp.2008.200

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/npp.2008.200

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Cognitive impairment in schizophrenia: aetiology, pathophysiology, and treatment

Molecular Psychiatry (2023)

-

Schizophrenia, Curcumin and Minimizing Side Effects of Antipsychotic Drugs: Possible Mechanisms

Neurochemical Research (2023)

-

Glutamatergic dysfunction in Schizophrenia

Translational Psychiatry (2022)

-

Non-invasive brain stimulation modulates GABAergic activity in neurofibromatosis 1

Scientific Reports (2022)

-

Memantine in neurological disorders – schizophrenia and depression

Journal of Molecular Medicine (2021)