Abstract

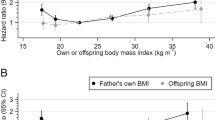

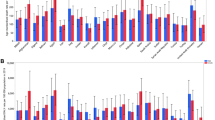

Reverse causality, in which obesity-induced disease leads to both weight loss and higher mortality, may bias observed associations between body mass index (BMI) and mortality, but the magnitude of that bias is unknown. The authors examined the impact of reverse causality and the exclusion of various diseases on the observed age-specific mortality ratios for BMI by using a state space model and sensitivity analyses. They found that reverse causality may decrease the ratios and induce a J-shaped curve on a graph. The authors further found that the net effect of excluding various diseases becomes a balance of competing forces, some tending to increase observed mortality ratios, where as others, such as selection based on common effects, may decrease them. Instead of studying just the change in observed mortality ratios, which can be misleading, investigators need to consider causal relationships and evaluate the conceptual and theoretical impact of any analytic maneuver. Analyses should be balanced with sensitivity approaches as well as with alternative analytic approaches such as the use of structural models, G-estimation, simulations and ancillary data from animal studies.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Flegal KM, Williamson DF, Pamuk ER, Rosenberg HM . Estimating deaths attributable to obesity in the United States. Am J Public Health 2004; 94: 1486–1489.

Flegal KM, Williamson DF, Pamuk ER . Letter: Flegal et al. respond. Am J Public Health 2005; 95: 932–933.

Robins JM . An analytic method for randomized trials with informative censoring: part 1. Lifetime Data Anal 1995; 1: 241–254.

Vaupel JW, Yashin AI . Heterogeneity's ruses: some surprising effects of selection on population dynamics. Am Stat 1985; 39: 176–185.

Greenland S . Absence of confounding does not correspond to collapsibility of the rate ratio or rate difference. Epidemiology 1996; 7: 498–501.

Flanders WD, Lin L, Pirkle JL, Caudill SP . Assessing the direction of causality in cross-sectional studies. Am J Epidemiol 1992; 135: 926–935.

Engeland A, Bjorge T, Selmer RM, Tverdal A . Height and body mass index in relation to total mortality. Epidemiology 2003; 14: 293–299.

Hernán MA, Hernández-Diaz S, Robins JM . A structural approach to selection bias. Epidemiology 2004; 15: 615–625.

Robins JM, Hernán MA, Brumback B . Marginal structural models and causal inference in epidemiology. Epidemiology 2000; 11: 550–560.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Flanders, W., Augestad, L. Adjusting for reverse causality in the relationship between obesity and mortality. Int J Obes 32 (Suppl 3), S42–S46 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2008.84

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2008.84

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

The magnitude and direction of the relationship between risk factor and cognition depends on age: a pooled analysis of 5 community-based studies

European Journal of Epidemiology (2024)

-

The association between BMI and mortality using early adulthood BMI as an instrumental variable for midlife BMI

Scientific Reports (2018)

-

Blood pressure and mortality: using offspring blood pressure as an instrument for own blood pressure in the HUNT study

Scientific Reports (2015)

-

Obesity Paradox should not interfere with public health efforts

International Journal of Obesity (2015)

-

Association between adherence to physical activity guidelines and health-related quality of life among individuals with physician-diagnosed arthritis

Quality of Life Research (2012)