Abstract

Purpose

To identify specific health-related quality of life (HRQOL) and functional vision concerns affecting children with cataracts and common associated conditions as expressed by children or one of their parents (proxy), and HRQOL concerns affecting the parents themselves.

Methods

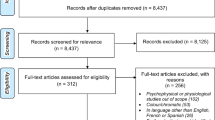

Individual semi-structured interviews were conducted with parents of children with cataracts (N=31) and with the children themselves (ages 5–17 years; N=16). Transcripts of recorded interviews were evaluated using NVivo software. Specific concerns were identified and coded, and broad themes were identified. The frequency of each theme was calculated, with the frequency of specific concerns within each theme.

Results

Regarding the child’s experience, 6 themes were identified: Visual Function (mentioned by 16 of 16 children (100%) and by 26 of 31 parents (84%), Social (94 and 65%), Treatment (81 and 90%), Worry (75 and 10%), Emotions (63 and 68%), and Physical Discomfort (63 and 26%). Worry showed the largest discrepancy between child and their parent; although 75% children reported Worry, only 6% of parents reported that their child experienced Worry (P=0.0009). Regarding the parents’ own experience, 5 themes were identified: Worry (100%), Compensation for Condition (100%), Treatment (94%), Emotions (90%), and Affects Family (52%).

Conclusions

A wide range of concerns were identified from interviews of children with cataracts and their parents. Concerns reflect the impact of cataracts in physical, emotional, and social domains, and specific concerns will be used for the development of questionnaires to quantify the quality of life and functional vision effects of cataracts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

A common cause of visual impairment in both children and adults is cataract.1, 2, 3, 4, 5 In adults with cataracts, numerous patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) have been used as primary or secondary end points to assess the effectiveness of surgery. The value of determining health-related quality of life (HRQOL) is well-recognized in ophthalmology practice and research and HRQOL has been found to be more highly correlated with patient-perceived disability than visual acuity.6, 7, 8, 9 Therefore, formal evaluation of HRQOL is being implemented in both clinical trials and clinical care. However, PROMs designed for adults treated for cataracts include questions about activities that are not applicable to pediatric patients, including driving, work-related activities, and independence, while ignoring pediatric domains like developmental milestones, academic achievement, and bullying. In addition, the intraoperative and postoperative adverse events and treatment challenges, and the postoperative persistence of visual impairment experienced by pediatric patients differ significantly from the experience of most adults treated for cataracts.

Available pediatric PROMs are primarily generic surveys designed to compare health status among children to gain a more complete understanding of the burden of a pediatric eye condition in the context of other pediatric diseases.10, 11 In general, such instruments lack sensitivity to vision-related changes in quality of life in clinical trials. To overcome this limitation, a number of pediatric vision-related PROMs and pediatric ophthalmic condition-specific PROMs have been developed, to evaluate vision-related function and health-related quality of life,12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19 but none of the instruments reflect the specific concerns of children with cataracts or their parents’ concerns.

In general, pediatric cataracts appear to have a significant impact, affecting both the child and the parent, but this conclusion is based on data from studies conducted with instruments designed to assess quality of life in other cohorts or other conditions.20 The purpose of the present study was to determine specific HRQOL and functional vision concerns of children with cataract and common associated conditions and their parents during the patient/parent open-ended interviews.

Materials and methods

The study was conducted at two sites. Institutional Review Board approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Boards at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota and the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX, USA. All procedures and data collection were conducted in a manner compliant with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act and all research procedures adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki Principles.

Participants

The parents of children with cataract ages 0–17 years were approached with information about the study and informed consent was obtained. In addition to parental consent, informed assent was obtained from children 7 years and older at the Mayo Clinic and 10 years and older at the Retina Foundation of the Southwest. Eligible children included patients who were attending clinical visits (Mayo Clinic), patients who were participating in research studies (Retina Foundation of the Southwest), and prior patients who were contacted by telephone and asked to participate in this research study (Retina Foundation of the Southwest). Both the child and one of their parents were enrolled. Clinical diagnoses were made by a pediatric ophthalmologist. The initial goal was to enroll 30 children, including a range of clinical severities, ages, and racial/ethnic diversity. This was a convenience sample size for interviews that we have found to be sufficient to achieve the desired redundancy where no new issues arise.14

Interviews

As in our prior study of HRQOL in esotropic children,21 individual, semi-structured, audio-recorded interviews were conducted by one of three examiners in a quiet examination room. The interview was structured around 12 questions for the child and 12 questions for the parent using an open-ended question format (Table 1).14, 21, 22 In order to elicit additional concerns not covered in the initial response to the question, probes such as, ‘How does that make you feel?’ or, ‘Tell me more about that,’ were used throughout the interview. In addition, the interviewer allowed any avenue of discussion regarding concerns, even if it led away from the core questions.

We attempted to interview all enrolled children aged 5–17 years. Whenever possible, the child was interviewed without the parent present (with verbal approval from the parent). If the parent was present, they were positioned out of the child’s line of sight and asked not to interrupt during the interview. One parent was interviewed for every enrolled child (for children under the age of 5 years, only the parent was interviewed). To allow the parent freedom to express concerns without having to worry about upsetting their child, the child either wore earphones and watched a movie on a portable DVD player or waited supervised in another room (with verbal approval from the parent).

Coding of interviews

Interviews were transcribed verbatim,21 then reviewed and coded using NVivo 10 software (QSR International, Doncaster, VIC, Australia). Specific concerns were identified and coded by assigning phrases to ‘nodes,’ adding new nodes as new areas of concern were identified. Separate nodes were created for parent concerns about the child’s experience (proxy report) and parent concerns about their own experience. Following a training exercise to harmonize coding standards,21 three reviewers coded interviews, with two reviewers independently coding each interview.

Clinical and demographic data

For each patient, additional information was collected: type of cataract, angle of strabismic deviation (largest of distance or near, by simultaneous prism and cover test when available, or if not available, by prism and alternate cover test, or Krimsky) grouped into one of three bins as either orthotropic, microtropic (less than 10 prism diopters (pd)), or moderate (10 pd or more), visual acuity, whether or not there was any global developmental delay, type of optical correction, current treatment, previous surgery, and prior treatment. Basic demographic data were also collected, including age, sex, race, and ethnicity of the child, parental age, parental highest level of education, type of housing, number of parents in the home, and childcare arrangements.

Analysis

Specific nodes were grouped into broader, over-arching themes. The frequency of nodes and themes were calculated separately for child concerns (derived from child interviews), proxy concerns (derived from parent interviews), and parent concerns (derived from parent interviews). 95% confidence intervals were calculated for the frequency of each theme. Frequencies between child and proxy pairs (for interviewed children 5–17 years old) were compared using a McNemar’s test.

Results

Cataract study population

We enrolled a total of 31 children (mean age 7.3±4.9 years, range 0 to 17 years) and 1 parent for each child. Of the 31 children, additional diagnoses included amblyopia (16; 52%), strabismus (13; 42%), and glaucoma (7; 23%), as well as other conditions affecting the cornea (3; 10%), iris (3; 10%), retina (5; 16%), optic nerve (2; 6%), cortical visual impairment (2; 6%), chronic anterior uveitis (1; 3%), or microphthalmia (1; 3%). Demographics of enrolled children and their parents are listed in Table 2. The enrolled cohort of children represented a range of clinical characteristics in terms of laterality of cataract, concurrent strabismus, visual acuity, global developmental delay, refractive correction, and treatments (Table 3). Eighteen eyes (29%) had moderate visual acuity deficit (20/40-20/80) and 15 eyes (24%) had severe visual acuity deficit. Eighty-seven percent had cataract surgery, 93% had optical correction (spectacles, contact lenses, interocular lenses), and 84% had been treated for amblyopia with patching or atropine (Table 3).

Child interviews: child concerns

Sixteen (89%) of 18 children aged 5–17 years were interviewed (2 children with severe developmental delay unable to be interviewed). From these child interviews, a total of 25 specific areas of concern (nodes) were created as the interviews were coded and these were subsequently grouped into six broad themes on the review of individual nodes: Visual Function (100%), Social (94%), Treatment (81%), Worry (75%), Emotions (63%), and Physical Discomfort (63%; Table 4). Within Visual Function, concerns regarding reduced vision were the most frequently mentioned specific concerns (14 of 16, 88%), including comments such as ‘I can’t see out of this eye’, ‘my vision isn’t really that good’, and ‘I see blurry out of this eye’. The most commonly mentioned specific concern within the Social theme was being different from others (14 of 16, 88%), with concerns like ‘they would comment on how I looked different’, ‘one eye is smaller than the other and they are different colors and sometimes one wanders off’, and ‘I have to sit at the front every time in class and they don’t have to’. Treatment concerns centered primarily around glasses (11 of 16, 69%) and patching (8 of 16; 50%). Twelve of 16 (75%) children reported worry, including worry that they might ‘damage or hurt my eye’ or ‘hit my eye,’ that ‘I may get blind’ or ‘have to go into a surgery and be blind,’ that ‘when I drive I could crash into someone because I can’t see out of this eye very well,’ and that ‘as I get older, will my eyesight deteriorate?’

Parent interviews: proxy-reported child concerns

Thirty-one parents were interviewed: 13 (42%) of 31 were parents of children aged 0–4 years (child was too young to be interviewed) and 18 were parents of children 5–17 years. The overall frequency of themes was similar to that of the children themselves, although treatment moved to the top of the list as the most frequently mentioned proxy concern (90%; Table 4). Treatment-related comments primarily concerned patching, such as ‘she really felt more vulnerable with one eye closed’ and glasses, such as ‘she has to wear the big thick glasses and everyone is like why, oh my gosh can you see this?’, and ‘No, I don't want a new pair [of glasses]; I just don't want to wear them.’ In comparing paired data from the 16 children aged 5–17 years and their parents, worry showed the largest discrepancy between child and proxy concerns. Although 75% children reported Worry, only 6% of parents reported that their child experienced Worry (P=0.0009).

Parent interviews: parent’s own concerns

From the 31 parent interviews, a total of 28 specific areas of concern were coded as relating to the parent’s own experience and 5 broad themes were identified: Worry (100%), Compensation for Condition (100%), Treatment (94%), Emotions (90%), and Affects Family (52%; Table 5). The most commonly mentioned specific concerns within the theme of Worry were worrying about vision (26 of 31, 84%), worrying about treatment (23 of 31, 74%), and worrying about the future (22 of 31, 71%; Table 5). These included worrying about ‘how the next eye appointment is going to go, is the vision progressing, where is it going to get to?’, worrying about ‘if she would have to have other eye surgeries’, worrying ‘if something were to happen to his right eye, his good eye’, worrying about ‘whether we are taking the right steps so that she is going to have good vision in the future. Just questioning everything that we are doing, constantly’, worrying about whether ‘her vision will be good enough to get a driver’s license when she is 16’, and worrying about the child driving and ‘not seeing something or having something happen to him because he didn’t see it.’

Every parent also mentioned concerns about the need to compensate for the child’s eye condition. These concerns included ‘making sure they had a contact lens case and saline in their possession when they went out or when they were at school so that if something happened they could change their contact lenses’, caution during sports activities including ‘because of the chance of retinal detachment,...we would always have to consider…is it safe for him to do’, ‘he uses eye protection in some of the sports he plays … and we kind of decided as a family he would not play tackle football’, and ‘we have chosen sports that we think will not physically harm his eyes’, and accommodations at school such as ‘I always send an e-mail to the teacher beforehand just saying can you keep [her] close to the front of the room’, ‘The first day of school I would always have to sit down with the teacher’, and ‘I have to constantly remind them that they need to take into account that the visual disability that he has, to slow down.’

Comparison with concerns of children with esotropia and their parents

Children with cataracts expressed social concerns more frequently than children with esotropia (94% vs 58%; Fisher's exact P=0.01). Parent proxies of children with cataract did not express a higher frequency of social concerns compared with parents of children with esotropia (65% vs 68%, P=0.8; Fisher's exact). Parents of children with cataract express similar frequency of worry themselves about social concerns (6 (19%) of 31) compared with parents of children with esotropia (20 (33%) of 60, P=0.2; Fisher's exact). In addition, compared with parents of children with esotropia, parents of children with cataracts reported significantly more concerns about the need to compensate for their child’s eye condition (100% vs 80%; Fisher's exact P=0.007) and about how their child’s eye condition affects the family (52% vs 23%; Fisher's exact P=0.01).

Discussion

During this patient/parent interview stage of developing new PROMs, a wide range of concerns was identified in semi-structured interviews of children with cataracts and their parents. Child concerns were grouped into six broad themes and parent concerns were grouped into five broad themes. The two most frequent themes for child concerns were Visual Function and Social. Every child expressed concerns about their visual function and most children were concerned about treatment and worried about their eyesight now and/or in the future. Although some parents appreciated similar concerns and worries regarding their child, it was not at the same frequency as the children themselves.

Nearly every child also expressed concern about social issues, with 88% reporting concerns about being different from other children. In contrast, only 23% of parent proxies reported the same concern and only 19% of parents reported worrying themselves about their child experiencing social difficulties. The social concerns expressed by the children in our interviews were also apparent in a prior study that used the PedsQL to assess children with cataracts; their psychosocial scores were similar to those obtained from children with severe, systemic chronic diseases.23 The frequency of social concerns expressed may be higher in parents of children treated for cataracts when strabismus is present.24

Few previous studies have reported HRQOL concerns in children with cataract. Hiatt25 evaluated parents of children in four age groups who had been treated for cataracts with a psychological questionnaire and reported psychosocial problems, including withdrawal, somatic complaints, social problems, attention deficit, aggressive behavior, abnormal behavior, anxiety, depression, and thought problems. These were found to be particularly significant in children who had been treated for bilateral cataracts and had poor visual acuity outcomes.25 With the exception of social concerns and physical discomfort, severe psychological problems were not concerns expressed by the parents in the present study.

Both the validated Children’s Visual Function Questionnaire (CVFQ) and validated LV Prasad-Functional Vision Questionnaire (FVQ) yielded lower competence and distance vision scores for patients with bilateral as compared with unilateral cataracts12, 26, 27 while those treated for unilateral cataracts had lower scores on the family impact and treatment difficulty subscales.12, 26 The Visual Function, Compensation for the Condition, Treatment, and Emotion concerns expressed during the interviews of the children and parents in the present study are consistent with these prior reports of reduced competence, family impact, and treatment difficulty.

A strength of the approach we are using to develop new PROMs for childhood eye diseases is that it follows the FDA directive for patient input by interviews to ensure content validity in the development of PROMs.28, 29, 30, 31, 32 The present study has some limitations. First, we had a small number of children/parents within each age bin and cataract subtype. Nevertheless, the aim of the study was to identify concerns from a diverse cohort of children treated for cataracts. Our study was not designed to evaluate the associations between clinical factors (eg, laterality and clinical subtype) and frequency of concerns. Second, we did not insist on the parent leaving the room while the child was interviewed, which may have limited the child’s freedom to express their concerns. We did position the parent out of the child’s line of sight to minimize this limitation and instructed parents not to comment during the child interview. Third, the concerns identified in this study may be influenced by coexisting the diagnoses of amblyopia, strabismus, and glaucoma, which were common, and, in isolated cases, diagnoses of cortical visual impairment, chronic anterior uveitis and conditions affecting the cornea, iris, retina, or optic nerve. Nevertheless, childhood cataracts typically exist alongside these other conditions, so identified concerns are likely representative of children with cataracts. Fourth, the relative frequencies of concerns expressed by this cohort of children and their parents reflect the open-ended interview format that was used to elicit these concerns. The relative frequencies of concerns could be different when evaluated using a standardized instrument that elicits responses to all possible concerns from every participant. Finally, our cohort was composed of children living in the USA and the concerns expressed may not be representative of other populations, including children with cataracts in developing countries.

Children treated for cataracts and their parents experience a wide range of concerns regarding visual function, treatment and symptoms. These concerns will be used to generate specific questions to populate questionnaires for children with cataracts, with a view to better quantifying the effects of cataracts on children and their parents in everyday life.

References

Foster A, Gilbert C, Johnson G . Changing patterns in global blindness: 1988-2008. Community Eye Health 2008; 21: 37–39.

Kalua K, Patel D, Muhit M, Courtright P . Causes of blindness among children identified through village key informants in Malawi. Can J Ophthalmol 2008; 43: 425–427.

Muhammad N, Maishanu NM, Jabo AM, Rabiu MM . Tracing children with blindness and visual impairment using the key informant survey in a district of north-Western Nigeria. Middle East Afr J Ophthalmol 2010; 17: 330–334.

Shirima S, Lewallen S, Kabona G, Habiyakare C, Massae P, Courtright P et al. Estimating numbers of blind children for planning services: findings in Kilimanjaro, Tanzania. Br J Ophthalmol 2009; 93: 1560–1562.

Gilbert C, Rahi JS, Quinn GE . Visual impairment and blindness in children. In: Johnson GJ, Minassian DC, Weale RA (eds). The Epidemiology of Eye Disease, 2nd edn. Arnold Publications: West SK, 2003.

Broman AT, Munoz B, Rodriguez J, Sanchez R, Quigley HA, Klein R et al. The impact of visual impairment and eye disease on vision-related quality of life in a Mexican-American population: proyecto VER. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2002; 43: 3393–3398.

Mangione CM, Phillips RS, Lawrence MG, Seddon JM, Orav EJ, Goldman L . Improved visual function and attenuation of declines in health-related quality of life after cataract extraction. Arch Ophthalmol 1994; 112: 1419–1425.

McAlinden C, Pesudovs K, Moore JE . The development of an instrument to measure quality of vision: the Quality of Vision (QoV) questionnaire. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2010; 51: 5537–5545.

Steinberg EP, Tielsch JM, Schein OD, Javitt JC, Sharkey P, Cassard SD et al. The VF-14. An index of functional impairment in patients with cataract. Arch Ophthalmol 1994; 112: 630–638.

Clarke SA, Eiser C . The measurement of health-related quality of life (QOL) in paediatric clinical trials: a systematic review. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2004; 2: 66.

Payot A, Barrington KJ . The quality of life of young children and infants with chronic medical problems: review of the literature. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care 2011; 41: 91–101.

Birch EE, Cheng CS, Felius J . Validity and reliability of the Children's Visual Function Questionnaire (CVFQ). J AAPOS 2007; 11: 473–479.

Khadka J, Ryan B, Margrain TH, Court H, Woodhouse JM . Development of the 25-item Cardiff Visual Ability Questionnaire for Children (CVAQC). Br J Ophthalmol 2010; 94: 730–735.

Hatt SR, Leske DA, Yamada T, Bradley EA, Cole SR, Holmes JM . Development and initial validation of quality-of-life questionnaires for intermittent exotropia. Ophthalmology 2010; 117: 163–168 e1.

Walline JJ, Jones LA, Chitkara M, Coffey B, Jackson JM, Manny RE et al. The Adolescent and Child Health Initiative to Encourage Vision Empowerment (ACHIEVE) study design and baseline data. Optom Vis Sci 2006; 83: 37–45.

Felius J, Beauchamp GR, Stager DR Sr., Van De Graaf ES, Simonsz HJ . The Amblyopia and Strabismus Questionnaire: English translation, validation, and subscales. Am J Ophthalmol 2007; 143: 305–310.

Decarlo DK, McGwin GJ, Bixler ML, Wallander J, Owsley C . Impact of pediatric vision impairment on daily life: results of focus groups. Optom Vis Sci 2012; 89: 1409–1416.

Cochrane GM, Marella M, Keeffe JE, Lamoureux EL . The Impact of Vision Impairment for Children (IVI_C): validation of a vision-specific pediatric quality-of-life questionnaire using Rasch analysis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2011; 52: 1632–1640.

Tadic V, Cooper A, Cumberland P, Lewando-Hundt G, Rahi JS, Vision-related Quality of Life Group. Development of the functional vision questionnaire for children and young people with visual impairment: the FVQ_CYP. Ophthalmology 2013; 120: 2725–2732.

O'Connor AR, Birch EE . Quality of life in pediatric cataracts. In: Wilson M, Trivedi R (eds). Pediatric Cataract Surgery: Techniques, Complications, and Management. Lippincott, Williams, & Wilkins: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2014. pp 379–386.

Liebermann L, Leske DA, Castaneda YS, Hatt SR, Wernimont SM, Cheng-Patel CS et al. Concerns of children with esotropia and their parents. J AAPOS 2016 in press.

Hatt SR, Leske DA, Bradley EA, Cole SR, Holmes JM . Development of a quality-of-life questionnaire for adults with strabismus. Ophthalmology 2009; 116 (139-144): e5.

Chak M, Rahi JS . & British Congenital Cataract Interest Group. The health-related quality of life of children with congenital cataract: findings of the British Congenital Cataract Study. Br J Ophthalmol 2007; 91: 922–926.

Uzun A, Atilla H . Health-related quality of life in children operated for pediatric cataracts. Eur J Ophthalmol 2014; 24: 707–711.

Hiatt RL . Rehabilitation of children with cataracts. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc 1998; 96: 475–515 discussion 515-7.

Lopes MC, Salomao SR, Berezovsky A, Tartarella MB . [Assessing vision-related quality of life in children with bilateral congenital cataracts]. Arq Bras Oftalmol 2009; 72: 467–480.

Paryani M, Khandekar RB, Dole K, Dharmadhikari S, Rishikeshi N . Visual outcome and impact on quality of life after surgeries differ in children operated for unilateral and bilateral cataract (Pune study 2011). Oman J Ophthalmol 2012; 5: 150–156.

Lasch KE, Marquis P, Vigneux M, Abetz L, Arnould B, Bayliss M et al. PRO development: rigorous qualitative research as the crucial foundation. Qual Life Res 2010; 19: 1087–1096.

Brod M, Tesler LE, Christensen TL . Qualitative research and content validity: developing best practices based on science and experience. Qual Life Res 2009; 18: 1263–1278.

Rothman M, Burke L, Erickson P, Leidy NK, Patrick DL, Petrie CD . Use of existing patient-reported outcome (PRO) instruments and their modification: the ISPOR good research practices for evaluating and documenting content validity for the use of existing instruments and their modification PRO task force report. Value Health 2009; 12: 1075–1083.

Patrick DL, Burke LB, Gwaltney CJ, Leidy NK, Martin ML, Molsen E et al. Content validity—establishing and reporting the evidence in newly developed patient-reported outcomes (PRO) instruments for medical product evaluation: ISPOR PRO good research practices task force report: Part 1—eliciting concepts for a new PRO instrument. Value Health 2011; 14: 967–977.

Patrick DL, Burke LB, Gwaltney CJ, Leidy NK, Martin ML, Molsen E et al. Content validity—establishing and reporting the evidence in newly developed patient-reported outcomes (PRO) instruments for medical product evaluation: ISPOR PRO good research practices task force report: Part 2—assessing respondent understanding. Value Health 2011; 14: 978–988.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants EY018810 (JMH), EY024333 (JMH, PI & EEB, Co-I), and EY022313 (EEB), Research to Prevent Blindness, New York, New York (unrestricted grant to the Department of Ophthalmology, Mayo Clinic), and Mayo Foundation, Rochester, Minnesota. None of the funding institutions had a role in design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or preparation, review or approval of the manuscript. JMH had access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health Grants EY024333 (JMH, PI and EEB, Co-I), EY022313 (EEB), and EY018810 (JMH), Research to Prevent Blindness, New York, New York (unrestricted grant to the Department of Ophthalmology, Mayo Clinic), and Mayo Foundation, Rochester, Minnesota.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Presented in part at the annual meeting of the Association for Vision and Research in Ophthalmology in Seattle, Washington, USA, 2016.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Castañeda, Y., Cheng-Patel, C., Leske, D. et al. Quality of life and functional vision concerns of children with cataracts and their parents. Eye 30, 1251–1259 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/eye.2016.134

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/eye.2016.134

This article is cited by

-

The impact of childhood glaucoma on psychosocial functioning and quality of life: a review of the literature

Eye (2023)

-

Testing the Efficacy of Family Health-Model of REBT on Family Values and Quality of Family Life Among Parents of Children with Visual Impairment

Journal of Rational-Emotive & Cognitive-Behavior Therapy (2022)

-

Is qualitative research under-represented in ophthalmology journals?

Eye (2017)