Abstract

We described and compared breast and ovarian screening practices in the 2-year period following test result disclosure in female non-carriers from BRCA1/2 mutation-positive families living in two countries, France and Quebec, Canada, which provide universal health care. Four hundred and two (France n=293; Quebec n=109) unaffected female non-carriers from BRCA-proven mutation families provided information about the uptake of mammography, clinical breast examination, breast self-examination, and ovarian ultrasounds using self-administered questionnaires. The frequency of screening practices between study cohorts were compared using logistic regression. Annual mammography was conducted in 23 and 43% of French and Quebecer women participants <50 years of age, respectively (adjusted odds ratio (aOR)=2.72; 95% confidence interval (CI), 1.08–6.81). In women ≥50 years of age, mammography was conducted in 49 and 65% of French and Quebecer participants (aOR=1.77; 95% CI, 0.07–4.51). Overall, 33% of French women and 39% of Quebecer women underwent at least one ovarian ultrasound during the 2-year period following BRCA1/2 test result with no significant difference between cohorts of women <50 years of age. Among older women, Quebecers reported more frequently than French women that they had undergone ultrasound once (aOR=3.00; 95% CI, 1.02–8.83). The frequency of cancer screening practices for female non-carriers from BRCA1/2 mutation-positive families in both France and Quebec exceeded those recommended for similarly aged women in the general population. Our findings highlight the need for clearcut recommendations on the follow-up of women from BRCA1/2 families who are not themselves carriers of a BRCA1/2 mutation.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

Women from BRCA1/2 mutation-positive families, but who are non-carriers, are not considered to have a high risk for breast and ovarian cancer.1, 2, 3 Despite some controversy about the magnitude of residual risk of breast cancer based on family history,2, 4 female non-carriers from BRCA1/2 mutation-positive families are currently encouraged to adopt the same screening practices as those recommended for women of their age in the general population.1, 5 Information with regard to cancer screening practices among non-carriers from BRCA1/2 mutation-positive families is scarce and inconsistent. An Australian study evaluating women who underwent BRCA1/2 testing in a research context showed that mutation non-carriers overuse screening.6 In contrast, an UK clinical cohort study revealed that over one-third of non-carriers ≥50 years of age had not had a mammogram within 3 years of follow-up, suggesting that some mutation non-carriers derive false reassurance from the genetic test results and avoid cancer screening.7

In countries with public health care, such as France and Canada, over-screening entails inappropriate use of public resources allocated to health care. As genetic testing for cancer susceptibility becomes more commonplace in clinical medicine, it is imperative to determine whether individuals undergoing testing benefit from such practices and are making optimum use of health resources corresponding to their actual risk levels. Risk management and follow-up recommendations for BRCA1/2 mutation carriers, which are available in both France and Canada,8, 9 suggest the same screening rates for female non-carriers from BRCA mutation-positive families as those applying to the general population. Briefly, in both countries, all women of age 50–69 years should undergo mammography every 2 years.10, 11 Although controversy surrounds the benefits of mammography for women of age 40–49 years, they can be granted access after discussing the risks and benefits with their physician. Routine mammographic screening is not recommended for women <40 years of age. Clinical breast examination (CBE) and breast self-examination (BSE) are complementary to mammography. In both countries, annual CBE is recommended for women of age 50–69 years, but BSE is not recommended as a routine method of breast cancer surveillance. Ultrasound (US) and CA-125 test are not recommended for ovarian cancer screening in either country. In this study, we describe and compare the cancer screening practices of female non-carriers from BRCA1/2 mutation-positive families in two countries that offer universal access to health care, France and Quebec.

METHODS

Participants

Participants from France were identified through a companion psychosocial study of the GENEPSO cohort.12 The GENEPSO cohort included BRCA1/2 mutation carriers recruited during routine consultation from the year 2000 to present at 26 cancer genetics clinics belonging to the French National Federation of Cancer Centres' Cancer Genetic Network. The companion psychosocial cohort study enrolled, through year 2006, both unaffected carriers and non-carriers from BRCA mutation-positive families identified in the GENEPSO cohort. Participants from Quebec were recruited from the INHERIT BRCAs research program, which provided French Canadian individuals with BRCA1/2 testing. Details concerning the study design and population are available.13, 14

In the cohorts from both countries, women eligible for this study were non-carriers from BRCA-positive families who were aware of their test result, had never had cancer, and were younger than 70 years of age at result disclosure. This study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Review Boards of the participating institutions, and all participants signed informed consent forms.

Data collection

Information with regard to the yearly frequency of breast and ovarian cancer screening practices during the 2-year period following result disclosure was collected similarly in both cohorts using self-administered, mail-in questionnaires that were completed 1 year post-disclosure in both groups, and then 1 and 2 years later by the French and Quebecer cohorts, respectively. The questions asked concerned the yearly frequency of mammography, CBE, BSE, US, and in the Quebec sample only, the CA-125 blood test. Item formulation differed slightly between the two surveys. To allow comparability between the two cohorts, the responses collected after each 1-year period were dichotomised to determine if a woman underwent a given test during that period. Reponses about year 1 and year 2 were then combined into a three-category variable referred to as ‘annually’, ‘once during the 2-year period’, and ‘none’, which reflected the frequency of the screening practices during the follow-up period. In the case of BSE, the three categories were ‘monthly or more often’, ‘less often than monthly’, and ‘never’.

All participants provided socio-demographic details, including age, education, marital and employment status, and parity. Although questions on several psychosocial variables were included in both surveys, only perceived lifetime breast cancer risk, as assessed on a five-point Likert scale in the first 6 months following test result disclosure, was measured in a sufficiently similar way in the two cohorts to be included in this analyses. Medical information such as personal and familial cancer history was obtained from the participants' medical (France) or research project (Quebec) files.

Analyses

The χ2 test was used to compare the socio-demographic data, cancer risk perception, familial history of cancer, and the timing of result disclosure in participants from France and Quebec. The proportions of women in each cohort who underwent a given test annually, once during the 2-year period, or never were calculated by age strata. BSE proportions were calculated on the basis of monthly frequency. Over-screening, according to French and Canadian recommendations for women from the general population, was defined as undergoing mammography before the age of 50 years or at a rate of more than once every 2 years after the age of 50 years. Testing by US or CA-125 was also considered over-screening. As no precise recommendations exist with regard to CBE and BSE, no over-screening criteria were defined for these practices.

Crude and adjusted comparisons on screening practices between the two cohorts were assessed by the odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals, using polytomic logistic regression models. The potential confounding effects of several variables were assessed by comparing the crude and adjusted models. Potential confounders included socio-demographics, breast cancer risk perception, family history of breast and ovarian cancer, and the timing of result disclosure. Statistical analyses were performed using the SAS 9.1 software.15 All significance levels were two-sided.

RESULTS

Participants

The 2-year questionnaire was completed by 293 (83%) of the 354 eligible unaffected non-carriers who participated in the psychosocial GENEPSO cohort companion study. The 3-year questionnaire was completed by 109 (81%) of the 134 eligible unaffected women with truly negative results who participated in the Quebec psychosocial study.

Patient characteristics differed between the two cohorts (Table 1). The French participants were younger than the Quebecers. Even though women who perceived their breast cancer risk as high or very high accounted for similar percentages within both cohorts, the Quebecer cohort contained a higher percentage of women who perceived their breast cancer risk as low or very low. Quebecers had a higher number of first-degree relatives affected by breast cancer as compared with the French women, whereas the opposite was true with regard to family history of ovarian cancer. French women received more recent disclosure of the BRCA1/2 test compared with the Quebec women.

Screening practices

France

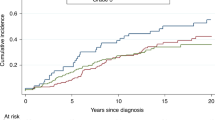

Nearly one-half of the French women in the 50–69 age group underwent annual mammography (Table 2). During the 2-year follow-up period, 78 and 44% of women in the 40–49 age group and the 30–39 age group, respectively, had at least one mammogram (Table 2). The overall rate of over-screening by mammography was 50% in the French cohort (Figure 1). An annual CBE was conducted in over 61% of French women in all age groups, whereas 11% of women did not have a CBE within the 2-year follow-up period. The overall proportion of women reporting no BSE was 35%. Thirty-three percent of French women underwent at least one US during the 2-year follow-up period with little proportion variation among age groups.

Quebec

Approximately two-thirds of the Quebecer women ≥40 years of age underwent an annual mammogram, and 40% of women of age 30–39 years had a mammogram at least once during the 2-year follow-up period (Table 3). The overall rate of over-screening by mammography in the Quebecer group was 64% (Figure 1). An annual CBE was conducted for most women (78%) in all age groups, whereas only 6% did not have a CBE during the 2-year follow-up period. Overall, 39% of Quebecers underwent US at least once during the 2-year follow-up period with fairly consistent proportion across age groups. The rate of over-screening by CA-125 blood test during the 2-year follow-up period was 30%, with 25% of women of age 50–69 years undergoing this test annually.

Comparisons between France and Quebec

With regard to breast cancer screening practices, the greatest difference between the two cohorts was for women ≤49 years of age (Table 4). In this younger age group, the proportions of Quebecers who had annual mammography, annual CBE, and reported performing BSE were significantly higher than those of the French women. These differences persisted after controlling for age, breast cancer risk perception, and family history of breast cancer. In women of age ≥50 years, the only difference detected was for CBE, adjusted OR showing more frequent use of CBE at least once during the 2-year follow-up period by Quebecers as compared with French women.

With regard to the frequency of US among women ≤49 years of age, no difference was observed between cohorts. Among older women, however, there was more frequent occurrence of US once during the 2-year follow-up period for Quebecers as compared with French women.

Comparisons with women from the general population

To determine whether screening was also overused by women in the general population in the two countries, we compared the rates of mammography over a 2-year period as reported in population-based surveys16, 17 with those observed in our cohorts of true non-carriers. No population data were available with respect to ovarian cancer screening. In both countries and for all age groups, the rates of mammography were substantially higher among non-carriers than among women from the general population (Table 5).

DISCUSSION

This comparative study examining cohorts from France and Quebec shows screening practices that exceed those recommended for similarly aged women of the general population in a substantial number of female non-carriers from BRCA mutation-positive families. Specifically, over one-half of French and Quebec non-carriers underwent unnecessary mammography during the 2-year period following result disclosure. In younger women, however, Quebecers were more frequently screened for breast cancer than French women. Ovarian US screening was also overused in 33 and 39% of non-carriers in France and Quebec, respectively.

One possible explanation for differences in practices between the two cohorts concerns the knowledge of physicians with respect to breast cancer screening. In France, guidelines for the management of BRCA1/2 carriers were available 8 years before the Canadian recommendations.8, 9, 18 Within the French recommendations are specific statements suggesting that non-carriers from families with a proven BRCA1/2 mutation have cancer risks similar to those of individuals in the general population. The Canadian recommendations on the follow-up of women having a family history of breast cancer do not clearly take into account the possibility that these women can obtain truly negative BRCA1/2 test results. Therefore, it is possible that Quebec physicians may have been reluctant to reduce the breast cancer screening rates of these non-carrier women from BRCA-positive families to those of women in the general population to fulfil their medical/ethical/legal obligations. Owing to their proximity to the United States, Quebec physicians may also be influenced by the American guidelines, which recommend annual mammography for women aged ≥40 years. The high frequency of ovarian cancer screening observed in both cohorts is intriguing. Although the frequency of US was similar in France and Quebec, the reasons behind over-screening may differ between the two countries because of variations in accessibility and attitudes toward US screening. For example, France has the highest number of recommended US scans of all European countries in the context of prenatal screening,19 with 47% of women averaging 4.5 US screens during pregnancy in 2003.20 In contrast, the Régie de l'Assurance-Maladie du Québec reimburses for only two US scans during pregnancy, with accessibility being limited by a shortage of radiologists.21 The high rates of US observed in the two populations deserve closer examination because ovarian cancer screening is not recommended, especially among women with negative BRCA1/2 test results.

Several limitations should be considered when assessing these findings. First, no information was collected in either the French or the Quebec survey with regard to the actual screening recommendations provided to women after they received their BRCA1/2 test result. Therefore, the reasons for the intensive cancer screening practices of non-carriers from BRCA mutation-positive families are unknown. Second, the screening practice information collected was based on self-reporting, and consequently they are subject to memory and social desirability biases. Although self-reports about screening practices are generally accurate,22 some women may have overestimated their frequency when asked to report them retrospectively.23 Third, comparison was made between two groups of women who were tested in different contexts. Although statistical comparisons were modelled using potential confounding factors for which the data were sufficient, the possibility of residual confounding cannot be ruled out.

When considering the public health impact of over-screening by female non-carriers from BRCA mutation-positive families, financial, psychosocial, and physical implications should be considered. In countries where health care is available to all, over-screening by true non-carriers constitutes inappropriate use of public resources. Furthermore, false-positive screening test results often lead to unnecessary invasive diagnostic procedures that entail additional costs, anxiety, and reluctance to participate in or withdraw from screening programmes.24, 25, 26 It has been estimated that 50% of women will have at least one false-positive test result for every 10 mammograms they undergo.27 Rates of false-positive test results are even higher in ovarian cancer screening.28 Given the intense screening practices of women with negative BRCA1/2 test results, further research is required on the psychosocial impact of false-positive screening results in this subgroup of women, who may be vulnerable to psychological distress. Moreover, it has not been established whether mammographic screening is safe before 40 years of age. The lifetime risk of radiation-induced breast cancer may be higher in women who start having mammograms at a relatively young age because of extended total exposure.29, 30 As our ability to estimate individual breast cancer risk improves through understanding additional genetic and environmental factors involved in familial clustering, it may eventually be feasible to target female non-carriers from BRCA mutation-positive families who may benefit from more intensive screening.31

Our findings have implications for the follow-up of women from families that carry BRCA1/2 mutations, but for whom genetic test results are negative. First, because most of these women will be referred to their primary care physicians and gynaecologists for future risk management, risk information based on the genetic test must be properly transmitted to the usual care settings. Second, clearcut recommendations are needed on the follow-up of women from BRCA1/2 families who do not carry the familial mutation. Third, such recommendations should be accompanied by continuous education of primary care physicians with respect to the rapidly evolving field of cancer genetics. Fourth, further research is required to develop and assess methods of fostering optimum use of screening in the context of cancer genetic testing. One challenge is to provide true non-carriers of familial BRCA1/2 mutations with complete information about the possible benefits and risks involved in further screening, without over-reassuring them.

References

Offit K, Garber J, Grady M et al: ASCO Curriculum: Cancer Genetics & Cancer Predisposition Testing. Alexandria, VA: ASCO, 2004.

Korde LA, Mueller CM, Loud JT et al: No evidence of excess breast cancer risk among mutation-negative women from BRCA mutation-positive families. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2011; 125: 169–173.

Domchek SM, Gaudet MM, Stopfer JE et al: Breast cancer risks in individuals testing negative for a known family mutation in BRCA1 or BRCA2. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2010; 119: 409–414.

Katki HA, Gail MH, Greene MH : Breast-cancer risk in BRCA-mutation-negative women from BRCA-mutation-positive families. Lancet Oncol 2007; 8: 1042–1043.

Berliner JL, Fay AM : Risk assessment and genetic counseling for hereditary breast and ovarian cancer: recommendations of the National Society of Genetic Counselors. J Genet Counsel 2007; 16: 241–260.

Dawson SJ, Price MA, Jenkins MA et al: Cancer risk management practices of noncarriers within BRCA1/2 mutation positive families in the Kathleen Cuningham Foundation Consortium for Research into Familial Breast Cancer. J Clin Oncol 2008; 26: 225–232.

Foster C, Watson M, Eeles R et al: Predictive genetic testing for BRCA1/2 in a UK clinical cohort: three-year follow-up. Br J Cancer 2007; 96: 718–724.

Eisinger F, Bressac B, Castaigne D et al: Identification and management of hereditary predisposition to cancer of the breast and the ovary (update 2004). Bull Cancer 2004; 91: 219–237.

Horsman D, Wilson BJ, Avard D et al: Clinical management recommendations for surveillance and risk-reduction strategies for hereditary breast and ovarian cancer among individuals carrying a deleterious BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2007; 29: 45–60.

Morrison B : Screening for Breast Cancer: Canadian Task Force on the Periodic Health Examination. Canadian Guide to Clinical Preventive Health Care. Ottawa: Health Canada, 1994, pp 788–795.

Agence Nationale d'Accréditation et d'Évaluation en Santé: Le dépistage du cancer du sein par mammographie dans la population générale: Étude d'évaluation technologique. Paris: ANAES, 1999.

Andrieu N, Easton DF, Chang-Claude J et al: Effect of chest X-rays on the risk of breast cancer among BRCA1/2 mutation carriers in the international BRCA1/2 carrier cohort study: a report from the EMBRACE, GENEPSO, GEO-HEBON, and IBCCS Collaborators' Group. J Clin Oncol 2006; 24: 3361–3366.

Simard J, Dumont M, Moisan AM et al: Evaluation of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation prevalence, risk prediction models and a multistep testing approach in French-Canadian families with high risk of breast and ovarian cancer. J Med Genet 2007; 44: 107–121.

Dorval M, Bouchard K, Maunsell E et al: Health behaviors and psychological distress in women initiating BRCA1/2 genetic testing: comparison with control population. J Genet Counsel 2008; 17: 314–326.

SAS Institute: Statistical Analysis System Version 9.1. Cary, NC: SAS Institute, 2006.

Statistique Canada: Enquête sur la santé dans les collectivités canadiennes Cycle 3.1 (2005): Fichier de microdonnées à grande diffusion, Ottawa, Statistique Canada, 2006.

Duport N, Bloch J : Dépistage du cancer du sein; in Guilbert P, Peretti-Watel, Beck F, Gautier A (eds): Baromètre Cancer 2005. Saint-Denis: INPES, 2006, pp 119–126.

Eisinger F, Alby N, Bremond A et al: Expertise collective INSERM-FNCLCC: Recommandations portant sur la prise en charge des femmes ayant un risque d'origine génétique de développer un cancer du sein et/ou de l'ovaire. Bull Cancer 1999; 86: 307–313.

Leschot NJ, Vejerslev LO : Proceedings of the EUCROMIC workshop on prenatal diagnosis. Eur J Hum Genet 1997; 5: 1–6.

Blondel B, Supernant K, Du Mazaubrun C, Breart G : Trends in perinatal health in metropolitan France between 1995 and 2003: results from the National Perinatal Surveys. J Gynecol Obstet Biol Reprod (Paris) 2006; 35: 373–387.

Breton P : Échographies foetales: Une crise majeure se dessine. La Presse: 22 mai, 2007, A9.

King ES, Rimer BK, Trock B, Balshem A, Engstrom P : How valid are mammography self-reports? Am J Public Health 1990; 80: 1386–1388.

Caplan LS, McQueen DV, Qualters JR, Leff M, Garrett C, Calonge N : Validity of women's self-reports of cancer screening test utilization in a managed care population. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2003; 12: 1182–1187.

Brett J, Austoker J, Ong G : Do women who undergo further investigation for breast screening suffer adverse psychological consequences? A multi-centre follow-up study comparing different breast screening result groups five months after their last breast screening appointment. J Public Health Med 1998; 20: 396–403.

Gram IT, Slenker SE : Cancer anxiety and attitudes toward mammography among screening attenders, nonattenders, and women never invited. Am J Public Health 1992; 82: 249–251.

Lerman C, Trock B, Rimer BK, Boyce A, Jepson C, Engstrom PF : Psychological and behavioral implications of abnormal mammograms. Ann Intern Med 1991; 114: 657–661.

Elmore JG, Barton MB, Moceri VM, Polk S, Arena PJ, Fletcher SW : Ten-year risk of false positive screening mammograms and clinical breast examinations. N Engl J Med 1998; 338: 1089–1096.

NIH Consensus Development Panel on Ovarian Cancer: NIH consensus conference: Ovarian cancer. Screening, treatment, and follow-up. JAMA 1995; 273: 491–497.

Preston DL, Mattsson A, Holmberg E, Shore R, Hildreth NG, Boice Jr JD : Radiation effects on breast cancer risk: a pooled analysis of eight cohorts. Radiat Res 2002; 158: 220–235.

Berrington de Gonzalez A, Reeves G : Mammographic screening before age 50 years in the UK: comparison of the radiation risks with the mortality benefits. Br J Cancer 2005; 93: 590–596.

Pharoah PD, Antoniou AC, Easton DF, Ponder BA : Polygenes, risk prediction, and targeted prevention of breast cancer. N Engl J Med 2008; 358: 2796–2803.

Acknowledgements

The GENEPSO study was supported by the Fondation de France and by La Ligue Nationale Contre le Cancer; the psychosocial companion project was supported by the Institut National du Cancer (Grant No. R08097AA/RPT08011AAA INCA). The INHERIT BRCAs research program was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (Grants Nos. CRT-43822 and CRN-87521) and the Canadian Breast Cancer Research Alliance (Grant No. 11383). Michel Dorval holds a Fonds de la Recherche en Santé du Québec Investigator Award; Jacques Simard is Chairholder of the Canada Research Chair in Oncogenetics. The funders had no role in study design, data collection, or in analysis and interpretation of the results, or in the decision to publish.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendices

Appendix I

The following members of the GENEPSO cohort contributed to this research: Hélène Cannoni-Zattara: CHU de la Timone, Marseille; Olivier Capron: Institut Gustave Roussy, Villejuif; Hélène Dreyfus: Clinique Sainte Catherine, Avignon; Thierry Frebourg: CHU Charles Nicolle, Rouen; Marc Frenay: Centre Antoine Lacassagne, Nice; Jean-Pierre Fricker: Centre Paul Strauss, Strasbourg; Paul Gesta: CHR Georges Renon, Niort; Rosine Guimbaud: Institut Claudius Regaud, Toulouse; Caroline Logeat, Inserm/IRD, Marseille; Elisabeth Luporsi: Centre Alexis Vautrin, Vandoeuvre les Nancy; Nguyen Tan Dat: Institut Jean Godinot, Reims; Hagay Sobol: Institut Paoli-Calmettes, Marseille; Laurence Venat-Bouvet: CHU Dupuytren, Limoges; Philippe Vennin: Centre Oscar Lambret, Lille.

Appendix II

The following members of INHERIT BRCAs contributed to this research: Paul Bessette: Service de gynécologie, Centre hospitalier Universitaire de Sherbrooke, Fleurimont; Peter Bridge: Molecular Diagnostics Laboratory, Alberta Children's Hospital, Calgary; Rachel Laframboise: Département de génétique, Centre hospitalier universitaire de Québec; Bernard Lespérance and Roxane Pichette: Hematology Oncology, Hôpital du Sacré-Cœur de Montréal, Université de Montréal, Montréal; Jean Lépine: Centre hospitalier régional de Rimouski, Rimouski; Elizabeth Maunsell: Faculté de médecine, Université Laval, Unité de recherche en santé des populations, Centre de recherche du CHA universitaire de Québec; Louise Provencher: Centre des maladies du sein Deschênes Fabia, Hôpital du Saint-Sacrement, Centre hospitalier affilié universitaire de Québec; Patricia Voyer: Clinique des maladies du sein, Carrefour de Santé de Jonquière.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Dorval, M., Noguès, C., Berthet, P. et al. Breast and ovarian cancer screening of non-carriers from BRCA1/2 mutation-positive families: 2-year follow-up of cohorts from France and Quebec. Eur J Hum Genet 19, 494–499 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1038/ejhg.2010.227

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ejhg.2010.227

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Survey of primary care physicians’ views about breast and ovarian cancer screening for true BRCA1/2 non-carriers

Journal of Community Genetics (2020)

-

Genetic counseling content: How does it impact health behavior?

Journal of Behavioral Medicine (2015)

-

Experience of BRCA1/2 mutation-negative young women from families with hereditary breast and ovarian cancer: a qualitative study

Hereditary Cancer in Clinical Practice (2013)

-

Comparison of the Screening Practices of Unaffected Noncarriers under 40 and between 40 and 49 in BRCA1/2 Families

Journal of Genetic Counseling (2013)

-

Family Communication Following BRCA1/2 Genetic Testing: A Close Look at the Process

Journal of Genetic Counseling (2013)