Abstract

Background:

Geriatric oncology guidelines state that fit older men with prostate cancer should receive curative treatment. In a population-based study, we investigated associations between age and non-receipt of curative treatment in men with localised prostate cancer, and the effect of clinical variables on this in different age groups.

Methods:

Clinically localised prostate cancers (T1–T2N0M0) diagnosed from 2002 to 2008 among men aged ⩾40 years, with hospital in-patient episode(s) within 1 year post-diagnosis, were included (n=5456). Clinical and socio-demographic variables were obtained from cancer registrations. Comorbidity was determined from hospital episode data. Logistic regression was used to investigate associations between age and non-receipt of treatment, adjusting for confounders; the outcome was non-receipt of curative treatment (radical prostatectomy or radiotherapy).

Results:

The percentage who did not receive curative treatment was 9.2%, 14.3%, 48.2% and 91.7% for men aged 40–59, 60–69, 70–79 and 80+ years, respectively. After adjusting for clinical and socio-demographic factors, age remained the main determinant of treatment non-receipt. Men aged 70–79 had a significant five-fold increased risk of not having curative treatment compared with men aged 60–69 (odds ratio (OR)=5.5; 95% confidence interval 4.7, 6.5). In age-stratified analyses, clinical factors had a higher weight for men aged 60–69 than in other age strata. Over time, non-receipt of curative treatment increased among men aged 40–59 and decreased among men aged 70–79.

Conclusion:

Age remains the dominant factor in determining non-receipt of curative treatment. There have been some changes in clinical practice over time, but whether these will impact on prostate cancer mortality remains to be established.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

The treatment of localised prostate cancer remains controversial. Radical prostatectomy and radiotherapy are the only treatment modalities considered to be curative. Evidence from clinical trials and population-based studies suggests that both of these treatments can result in improved disease-free and patient survival, with the magnitude of the benefit depending on the risk category of the tumour (Bill-Axelson et al, 2008; Ladjevardi et al, 2010; Schymura et al, 2010; Abdollah et al, 2011; Wilt et al, 2012; Abdollah et al, 2012a, 2012b; Aizer et al, 2013).

In developed countries, 53% of all prostate cancers are diagnosed in men aged 70 and older, in Ireland these figures were estimated to be 36% in 2008, and this age category contains 83% of estimated prostate cancer deaths (Ferlay et al, 2010). Before making treatment decisions for older patients, oncologists, radiation therapists and surgeons are advised to comprehensively evaluate patient fitness and functional status (Droz et al, 2010b). Geriatric oncology guidelines strongly recommend that treatment decisions in prostate cancer should be based on the patient’s ‘physiological age’ (Droz et al, 2010b) and not their chronological age. The same guidelines state that fit older men should have the same treatment options as their younger counterparts (Droz et al, 2010a). Based on these, it is expected that a subset of fit older men diagnosed with prostate cancer can have a survival benefit if undergoing curative treatment. Despite this, some studies – mainly from North America and/or clinical series from large specialised centres – suggest that advanced age remains a major determinant of treatment non-receipt. As few population-based studies have evaluated the relationship between age and prostate cancer treatment in European populations (Houterman et al, 2006; Fairley et al, 2009; Jegu et al, 2010), we conducted a population-based study investigating associations between age and non-receipt of curative treatment in men with localised prostate cancer, and the effect of patient and tumour characteristics on treatment non-receipt in different age groups.

Materials and Methods

The study setting was in Ireland, which was estimated to have the highest prostate cancer incidence rate in Europe in 2008 (Ferlay et al, 2010). Extensive use of PSA testing in primary care and a high rate of prostate biopsy among men with raised PSA levels (Carsin et al, 2010), results in the majority of cancers being localised at diagnosis (National Cancer Registry Ireland, 2010)

Data sources

Tumour, socio-demographic and treatment details for men aged 40 and older diagnosed with clinically localised prostate cancer (cT1-2N0M0) during 2002–2008 were obtained from the National Cancer Registry, which records all newly diagnosed cancers in the Irish population (National Cancer Registry Ireland, 2012). The Hospital In-Patient Enquiry Scheme (HIPE) (ESRI, 2012) collects administrative data on in-patient and day case discharge episodes from all public hospitals in Ireland. All episodes from the date of cancer diagnosis were linked to the prostate cases using probabilistic-matching methods. An algorithm (Quan et al, 2005) containing the ICD-10-AM codes corresponding to Charlson et al (1987) comorbid conditions, was used to assign a comorbidity score to each case. This was derived from the primary and up to 19 secondary diagnostic conditions recorded on all episodes in the year after the prostate cancer diagnosis.

Study data set

The analysis data set included those prostate cancer cases with a HIPE record within 1 year after diagnosis. Curative treatment was defined as radical prostatectomy (with or without other therapies) or radiotherapy (including brachytherapy; with or without adjuvant androgen deprivation therapy).

Potential explanatory variables were coded as follows: clinical T (cT1, cT2); Gleason score (2–7, 8–10 and unknown); comorbidity (Charlson score 0, 1 and 2+); age at diagnosis (40–59, 60–69, 70–79 and 80+); marital status (married and other: divorced, widowed, other and unknown); smoking status at diagnosis (current and other: ex-smokers and unknown smoking status); deprivation level of area of residence (based on the address at diagnosis; from least deprived (1) to most deprived (5)) (Kelly and Teljeur, 2007); area of residence at diagnosis (Dublin Mid-Leinster, Dublin North-East, South and West); and year of diagnosis (continuous).

Statistical analysis

The outcome was non-receipt of curative treatment. Logistic regression was used to estimate the odds ratio (OR) for each age-group and to explore the extent to which the effect of age was changed by the inclusion of other variables in the model. Therefore, the risk estimates reported for age are from: (i) univariate analyses; (ii) analyses adjusted for tumour-related factors; (iii) analyses adjusted for tumour and patient-related clinical factors; (iv) multivariate analyses (adjusted for tumour- and patient-related clinical factors and socio-demographic factors). The selection of variables in the multivariate model was by stepwise backward elimination; variables which were significant on likelihood ratio tests (P<0.05) were retained. Interactions between age and other variables were investigated; significant interactions were kept in the final model. This model was used to estimate the predicted probabilities (Williams, 2012) of not undergoing curative treatment for each category of Gleason score, cT and Charlson index within each age group. Finally, model goodness-of-fit was assessed by the Hosmer–Lemeshow test (Hosmer et al, 1997). Age-stratified analyses were conducted to identify factors significantly associated with non-receipt of curative treatment in men in different age groups. The same approach to model fitting as described above was used.

Results

Of 9716 men diagnosed with clinically localised prostate cancer in Ireland during 2002–2008, 5456 (56.2%) had a HIPE record within a year of diagnosis and were included in the analysis.

Baseline characteristics

Baseline characteristics by age group are shown in Table 1. Mean age at diagnosis was 66.3 years; 35% of cases were diagnosed among men aged 70 and over. The percentage of cases aged 70 and over decreased over time. High-risk disease (Gleason 8–10) was more common in older men, but there was no difference in the distribution of tumour size by age group. The percentage of cases with comorbidities increased with age. Older men were less likely to be married or to be smokers.

Table 2 shows the distribution of curative treatment, by modality (radical prostatectomy or radiotherapy), for each age group. Overall, 28% of patients did not have curative treatment. This percentage increased with age. Among those undergoing treatment, radical prostatectomy was essentially confined to men under 70. Use of radiotherapy increased with age, peaking in the 65–69 age group, then declined among older men.

Age and non-receipt of curative treatment

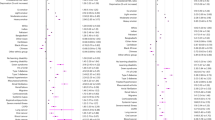

Table 3 shows the association between age and non-receipt of curative treatment, progressively adjusted for confounders. Overall, the ORs for age changed little between the univariate and adjusted models. In the final multivariate analysis, men aged 70–79 were five times more likely not to have curative treatment than the reference group (60–69). Men aged 80 or older were 50 times more likely than those aged 60–69 not to be treated curatively.

Predicted probability of non-receipt of curative treatment

Figure 1A–C show the predicted probabilities, from the multivariate model, of not receiving curative treatment, for different categories of Gleason score, clinical T and comorbidity, by age. In all age groups, cases with Gleason scores 2–7 had a slightly lower probability of not being treated than other cases. Similarly, in all age groups, cases with cT1 tumours were more likely not to be treated than cT2 tumours, the difference being more pronounced among those 70–79 years old. The effect of comorbidity differed between age groups; the biggest difference between cases with and without comorbidities was observed within the 40–59 age group, while the smallest was among patients aged 80 and older.

Age-stratified analyses

Table 4 shows, by age group, associations between clinical factors and non-receipt of curative treatment from models adjusted for significant patient-related variables. Within three of the four age strata (60–69, 70–79 and 80+), older patients were significantly more likely not to undergo curative treatment compared with younger patients. In the youngest stratum (40–59 years), the risk of non-treatment significantly increased over time. In contrast, in men aged 70–79, the risk of not being treated decreased significantly over time. Gleason score did not predict treatment non-receipt for men aged 40–59 and 70–79. Among men aged 60–69, those with aggressive disease, or unknown Gleason score, were more likely not to undergo curative treatment than those with Gleason score 2–7. Among men aged 60–69 and 70–79, those with cT1 tumours were significantly more likely not to undergo treatment than men with cT2 tumours. For the youngest men, having one comorbid condition did not affect the likelihood of not receiving treatment, but those with Charlson comorbidity score of 2 or more were significantly more likely not to be treated than those with no comorbid conditions. A dose–response relationship between comorbidity and likelihood of not being treated curatively was observed among men aged 60–69 and 70–79.

Discussion

Main findings

In this population-based analysis, age at diagnosis was the major predictor of non-receipt of curative treatment in men with clinically localised prostate cancer; this effect was little attenuated by adjustment for clinical and socio-demographic characteristics. Men aged 70 and older did not receive curative treatment significantly more frequently than their younger counterparts, and age influenced treatment non-receipt more than Gleason score, clinical tumour stage or comorbid conditions. The stratified analyses showed that the factors associated with treatment non-receipt differed by age. The influence of clinical factors was greater for men aged 60–69 than for other age groups and those diagnosed with high-risk disease had less curative treatment than those diagnosed with low-risk disease. Treatment non-receipt decreased over time among men aged 70–79.

All prostate cancer treatment decisions involve weighing benefits and costs, taking into account several factors such as disease severity and life expectancy. Our results show that decisions are being made based on chronological age more than on other relevant clinical factors, with younger men being more systematically treated and many older men not having curative treatment.

Curative treatment of prostate cancer in older men: current evidence

Older men are more likely to be diagnosed with more aggressive disease and also more likely to die from prostate cancer than younger men (Bechis et al, 2011). The optimal treatment of localised prostate cancer remains controversial; it is not clear whether radical prostatectomy or radiotherapy is superior, and active surveillance seems a suitable management strategy for some older patients; however, few studies present results stratified by age. A randomised trial of radical prostatectomy compared with watchful waiting, conducted in a non-PSA-screening setting, showed no reduction in recurrence and prostate cancer mortality in the prostatectomy group for men 65 and over (Bill-Axelson et al, 2008). Recent evidence, mostly observational, suggests that, men with high-grade localised prostate cancer can expect a survival benefit from radical prostatectomy (Ladjevardi et al, 2010; Vickers et al, 2012; Wilt et al, 2012; Xia et al, 2012). A population-based study of men aged 65 and over found that those having radical prostatectomy had only half the risk of prostate cancer-specific mortality of those managed by observation (Abdollah et al, 2011), but these results may have been influenced by uncontrolled differences between the treatment groups. Radiotherapy is firmly established as a more effective treatment for high-risk localised prostate cancer than observation (Heidenreich et al, 2011). Few randomised clinical trials have compared outcomes between radical prostatectomy and radiotherapy. One trial suggested that, for low/intermediate-risk tumours, radiotherapy and radical prostatectomy offer similar biochemical disease-free survival, but that radiotherapy is more effective than surgery for those with high-risk disease (Aizer et al, 2009) findings corroborated by a population-based study (DeGroot et al, 2012). Two other population-based studies have suggested that patients with high-risk disease and without comorbidity benefit more from surgery than radiotherapy (Ladjevardi et al, 2010; Abdollah et al, 2012a).

For a subset of older men diagnosed with indolent/low-risk prostate cancer, there is evidence that curative treatment does not offer a survival benefit compared with watchful waiting or active surveillance. The SPCG-4 and PIVOT trials suggest that radical prostatectomy does not offer a survival benefit over observation (Vickers et al, 2012; Wilt et al, 2012). Population-based studies have found that curative treatment (Ladjevardi et al, 2010) or radiotherapy (Abdollah et al, 2012b) seem to offer little or no benefit compared with observation.

In summary, current evidence suggests that for high-risk localised disease curative treatment provides better outcomes than observation, but it is not clear if radical prostatectomy offers a survival benefit over radiotherapy, but all patients with localised high-risk prostate cancer who could potentially benefit from curative treatment should be considered for it, including fit older men having >10 years of life expectancy. In some older men with low-risk disease, curative treatment can be omitted, avoiding side effects that affect quality of life (Wilt et al, 2008) without obtaining a survival benefit.

However, in our study no clinical pattern of treatment decision making was identified in our analysis and age was the strongest factor predicting treatment receipt, suggesting that clinical decisions are being driven by age and not by clinical characteristics. Age was clearly the main factor affecting treatment receipt, with older men significantly less likely to be treated curatively. Older men more often have comorbidity, and this may make curative treatment inappropriate. Radical prostatectomy was rare in men over 70 years and radiotherapy receipt decreased steadily after 75 years of age. However, comorbidity had a limited impact on treatment receipt and the effect of age, per se, remained very strong after adjustment for comorbidity. Tumour aggressiveness (Gleason score) did not affect treatment receipt for those aged 70–79.

Life expectancy is increasing in developed countries and older men constitute a heterogeneous group regarding comorbidities, physiological ageing, fitness, nutritional and functional status. As stated by geriatric oncology guidelines, treatment decisions must be individualised and a balance between benefit and risk needs to be established before managing older patients. Geriatric oncology guidelines recommend that older men with prostate cancer should be managed according to their general health status rather than chronological age (Droz et al, 2010b) Moreover, these point out that fit senior men are suitable for the same forms of standard cancer treatment as their younger counterparts, including surgery (Droz et al, 2010b). Specifically, it has been suggested that life expectancy should be taken in account when determining the potential benefit of treatment, with a life expectancy of at least 10 years as a cutoff (Heidenreich et al, 2011) Life expectancy for men in Ireland is among the highest in Europe – 13 years at 70 and 10 years at 75 – suggesting that curative treatment has the potential to benefit many fit senior men (Central Statistics Office, 2009).

Radical prostatectomy and radiotherapy have side effects and if the treatment is not found to offer a survival benefit then it should not be offered to patients. All treatments involve weighing costs, and benefits for the patient and prostate cancer treatments are frequently associated with significant side effects (Wilt et al, 2008; Gomella et al, 2009), although the side effects of radiotherapy, at least, do not appear to increase with age (Jani et al, 2005).

Similar studies in other settings have also found that age was related to non-receipt of curative treatment (both radiotherapy and radical prostatectomy) for localised disease (Houterman et al, 2006; Jegu et al, 2010; Schymura et al, 2010). A large UK population-based study of men without metastatic disease found that 88% of those aged 75 and older did not have curative treatment (Fairley et al, 2009). In a small population-based study from the Netherlands (n=505), 88% of patients aged 70 and older did not undergo curative treatment (Houterman et al, 2006). However, US studies show higher frequencies of curative treatment among men aged 75 and older; 41% in one study (Schymura et al, 2010) and between 46% (high-risk) and 59% (low/intermediate risk) in another, with little effect of comorbidity (Roberts et al, 2011). One study, from the US using data from Veteran Affairs Medical Centres, reported overtreatment of men with low-risk disease and significant comorbidity (Daskivich et al, 2011).

Further research would be valuable to better understand the reasons for clinicians’ treatment recommendations and decisions in older men with localised prostate cancer.

Our study suggests that not only are older men probably undertreated with curative therapies but they are often offered ADT possibly in the belief that this is a low-risk alternative. In our population, 51% of those aged 70 and older who did not have curative treatment had ADT (data not shown). However, ADT has been associated with a range of side effects, including increased risks of cardiovascular and thrombotic disease and of fractures, and a range of other physiological and psychological side effects, which can impact on quality of life (Fitzpatrick, 2008; Wilt et al, 2008; Gomella et al, 2009; Van Hemelrijck et al, 2012), without offering a survival benefit (Lu-Yao et al, 2008). These side effects are more pronounced among older patients and can increase mortality (Mohile et al, 2009).

Strengths and limitations

Although the study data set was restricted to men with a hospital episode in the year after diagnosis, the baseline characteristics of prostate cancers with and without a hospital episode were similarly distributed. The frequency of non-treatment was higher among men whose registrations were not linked to hospital episode data (38% vs 28% in the study population), suggesting that our analysis underestimated the overall level of non-treatment. We had no information on treatments offered to, but declined by, patients, but the observed association with age is so strong that it is unlikely that it would be much attenuated by the inclusion of these episodes in the model. PSA values at diagnosis were unavailable, thus the risk stratification was determined by Gleason score alone. Finally, we did not have access to factors such as fitness for treatment, functional, dependence or nutritional status, which may be important determinants of treatment (Droz et al, 2010a). Nevertheless, there seemed to be a very definite change in treatment allocation at age 70, unlikely to be entirely accounted by these factors.

The main study strengths are its population basis and the inclusion of comorbidity, a major determinant of clinical decisions, as an explanatory variable. Few population-based cancer registries have access to comprehensive information on comorbidity (or, indeed, treatment) and this study adds to the evidence base on prostate cancer treatment in routine clinical practice in Europe.

Conclusions

Although geriatric oncology guidelines advise clinicians to take treatment decisions based on the overall health of the patient, this analysis suggests that chronological age remains the strongest predictor of curative treatment in men with localised prostate cancer. However, there is some evidence of change in treatment levels over time, suggesting evolution in clinical practice. Whether this will impact on prostate cancer-specific mortality rates remains to be established.

Change history

09 July 2013

This paper was modified 12 months after initial publication to switch to Creative Commons licence terms, as noted at publication

References

Abdollah F, Schmitges J, Sun M, Jeldres C, Tian Z, Briganti A, Shariat SF, Perrotte P, Montorsi F, Karakiewicz PI (2012a) Comparison of mortality outcomes after radical prostatectomy versus radiotherapy in patients with localized prostate cancer: a population-based analysis. Int J Urol 19: 836–844, (author reply 844–845).

Abdollah F, Sun M, Schmitges J, Thuret R, Tian Z, Shariat SF, Briganti A, Jeldres C, Perrotte P, Montorsi F, Karakiewicz PI (2012b) Competingrisks mortality after radiotherapy vs. observation for localized prostate cancer: a population-based study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 84: 95–103.

Abdollah F, Sun M, Schmitges J, Tian Z, Jeldres C, Briganti A, Shariat SF, Perrotte P, Montorsi F, Karakiewicz PI (2011) Cancer-specific and other-cause mortality after radical prostatectomy versus observation in patients with prostate cancer: competing-risks analysis of a large North American population-based cohort. Eur Urol 60: 920–930.

Aizer AA, Chen MH, Hattangadi J, D’Amico AV (2013) Initial management of prostate-specific antigen-detected, low-risk prostate cancer and the risk of death from prostate cancer. BJU Int; e-pub ahead of print 8 March 2013; doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2012.11789.x.

Aizer AA, Yu JB, Colberg JW, McKeon AM, Decker RH, Peschel RE (2009) Radical prostatectomy vs. intensity-modulated radiation therapy in the management of localized prostate adenocarcinoma. Radiother Oncol 93: 185–191.

Bechis SK, Carroll PR, Cooperberg MR (2011) Impact of age at diagnosis on prostate cancer treatment and survival. J Clin Oncol 29: 235–241.

Bill-Axelson A, Holmberg L, Filén F, Ruutu M, Garmo H, Busch C, Nordling S, Häggman M, Andersson SO, Bratell S (2008) Radical prostatectomy versus watchful waiting in localized prostate cancer: the Scandinavian prostate cancer group-4 randomized trial. J Natl Cancer Inst 100: 1144–1154.

Carsin AE, Drummond FJ, Black A, van Leeuwen PJ, Sharp L, Murray LJ, Connolly D, Egevad L, Boniol M, Autier P, Comber H, Gavin A (2010) Impact of PSA testing and prostatic biopsy on cancer incidence and mortality: comparative study between the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland. Cancer Causes Control 21: 1523–1531.

Central Statistics Office (2009) Irish Life Table No. 15 (accessed 30th April 2013). Available from http://www.cso.ie/en/media/duplicatecsomedia/newmedia/releasespublications/documents/birthsdm/current/irishlife.pdf.

Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR (1987) A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis 40: 373–383.

Daskivich TJ, Chamie K, Kwan L, Labo J, Palvolgyi R, Dash A, Greenfield S, Litwin MS (2011) Overtreatment of men with low-risk prostate cancer and significant comorbidity. Cancer 117: 2058–2066.

DeGroot JM, Brundage MD, Lam M, Rohland SL, Heaton J, Mackillop WJ, Siemens DR, Groome PA (2012) Prostate cancer-specific survival differences in patients treated by radical prostatectomy versus curative radiotherapy. Can Urol Assoc J, http://dx.doi.org/10.5489/cuaj.11294.

Droz JP, Balducci L, Bolla M, Emberton M, Fitzpatrick JM, Joniau S, Kattan MW, Monfardini S, Moul JW, Naeim A (2010a) Background for the proposal of SIOG guidelines for the management of prostate cancer in senior adults. Crit Rev Oncol 73: 68.

Droz JP, Balducci L, Bolla M, Emberton M, Fitzpatrick JM, Joniau S, Kattan MW, Monfardini S, Moul JW, Naeim A, van Poppel H, Saad F, Sternberg CN (2010b) Management of prostate cancer in older men: recommendations of a working group of the International Society of Geriatric Oncology. BJU Int 106: 462–469.

ESRI (2012) The Economic and Social Research Institute (2012) Hospital In-patient Enquiry Scheme (HIPE) (accessed 4 February 2013). Available from http://www.esri.ie/health_information/hipe.

Fairley L, Baker M, Whiteway J, Cross W, Forman D (2009) Trends in non-metastatic prostate cancer management in the Northern and Yorkshire region of England, 2000–2006. Br J Cancer 101: 1839–1845.

Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, Forman D, Mathers C, Parkin DM (2010) GLOBOCAN 2008 v2.0, Cancer Incidence and Mortality Worldwide: IARC CancerBase No. 10 (accessed 4 February 2013). Available from http://globocan.iarc.fr.

Fitzpatrick JM (2008) Management of localized prostate cancer in senior adults: the crucial role of comorbidity. BJU Int 101: 16–22.

Gomella LG, Johannes J, Trabulsi EJ (2009) Current prostate cancer treatments: effect on quality of life. Urology 73: S28–S35.

Heidenreich A, Bellmunt J, Bolla M, Joniau S, Mason M, Matveev V, Mottet N, Schmid HP, van der Kwast T, Wiegel T, Zattoni F, . European Association of Urology (2011) EAU guidelines on prostate cancer. Part 1: screening, diagnosis, and treatment of clinically localised disease. Eur Urol 59: 61–71.

Hosmer DW, Hosmer T, Le Cessie S, Lemeshow S (1997) A comparison of goodness-of-fit tests for the logistic regression model. Stat Med 16: 965–980.

Houterman S, Janssen-Heijnen ML, Verheij CD, Kil PJ, van den Berg HA, Coebergh JW (2006) Greater influence of age than co-morbidity on primary treatment and complications of prostate cancer patients: an in-depth population-based study. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis 9: 179–184.

Jani AB, Parikh SD, Vijayakumar S, Gratzle J (2005) Analysis of influence of age on acute and chronic radiotherapy toxicity in treatment of prostate cancer. Urology 65: 1157–1162.

Jegu J, Tretarre B, Velten M, Guizard AV, Danzon A, Buemi A, Colonna M, Kadi-Hanifi AM, Ganry O, Molinie F, Bara S, Rebillard X, Grosclaude P (2010) Prostate cancer management and factors associated with radical prostatectomy in France in 2001. Prog Urol 20: 56–64.

Kelly A, Teljeur C (2007) The national deprivation index for health & health services research. Small Area Health Research Unit Technical Report. Small Area Health Research Unit, Trinity College Dublin; 2007.

Ladjevardi S, Sandblom G, Berglund A, Varenhorst E (2010) Tumour grade, treatment, and relative survival in a population-based cohort of men with potentially curable prostate cancer. Eur Urol 57: 631–638.

Lu-Yao GL, Albertsen PC, Moore DF, Shih W, Lin Y, DiPaola RS, Yao SL (2008) Survival following primary androgen deprivation therapy among men with localized prostate cancer. JAMA 300: 173–181.

Mohile SG, Mustian K, Bylow K, Hall W, Dale W (2009) Management of complications of androgen deprivation therapy in the older man. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 70: 235–255.

National Cancer Registry Ireland (2010) Cancer Trends No. 3. Recent trends in prostate cancer (accessed 4 February 2013). Available from http://www.ncri.ie/pubs/pubfiles/prostate%20trends.pdf.

National Cancer Registry Ireland (2012) Data Quality and Completeness at the Irish National Cancer Registry (accessed 4 February 2013). Available from: http://www.ncri.ie/pubs/pubfiles/CompletenessQuality.pdf.National Cancer Registry Ireland (2010).

Quan H, Sundararajan V, Halfon P, Fong A, Burnand B, Luthi JC, Saunders LD, Beck CA, Feasby TE, Ghali WA (2005) Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Med Care 43: 1130–1139.

Roberts CB, Albertsen PC, Shao YH, Moore DF, Mehta AR, Stein MN, Lu-Yao GL (2011) Patterns and correlates of prostate cancer treatment in older men. Am J Med 124: 235–243.

Schymura MJ, Kahn AR, German RR, Hsieh MC, Cress RD, Finch JL, Fulton JP, Shen T, Stuckart E (2010) Factors associated with initial treatment and survival for clinically localized prostate cancer: results from the CDC-NPCR Patterns of Care Study (PoC1). BMC Cancer 10: 152.

Van Hemelrijck M, Garmo H, Holmberg L, Stattin P, Adolfsson J (2012) Multiple events of fractures and cardiovascular and thromboembolic disease following prostate cancer diagnosis: results from the population-based PCBaSe Sweden. Eur Urol 61: 690–700.

Vickers A, Bennette C, Steineck G, Adami HO, Johansson JE, Bill-Axelson A, Palmgren J, Garmo H, Holmberg L (2012) Individualized estimation of the benefit of radical prostatectomy from the Scandinavian Prostate Cancer Group randomized trial. Eur Urol 62: 204–209.

Williams R (2012) Using the margins command to estimate and interpret adjusted predictions and marginal effects. Stata J 12 (2): 308–331.

Wilt TJ, Brawer MK, Jones KM, Barry MJ, Aronson WJ, Fox S, Gingrich JR, Wei JT, Gilhooly P, Grob BM, Nsouli I, Iyer P, Cartagena R, Snider G, Roehrborn C, Sharifi R, Blank W, Pandya P, Andriole GL, Culkin D, Wheeler T Prostate Cancer Intervention versus Observation Trial (PIVOT) Study Group (2012) Radical prostatectomy versus observation for localized prostate cancer. N Engl J Med 367: 203–213.

Wilt TJ, MacDonald R, Rutks I, Shamliyan TA, Taylor BC, Kane RL (2008) Systematic review: comparative effectiveness and harms of treatments for clinically localized prostate cancer. Ann Intern Med 148: 435–448.

Xia J, Trock BJ, Cooperberg MR, Gulati R, Zeliadt SB, Gore JL, Lin DW, Carroll PR, Carter HB, Etzioni R (2012) Prostate cancer mortality following active surveillance versus immediate radical prostatectomy. Clin Cancer Res 18: 5471–5478.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the National Cancer Registry tumour registration officers, Data Team and IT staff for collecting and processing the cancer registrations, and conducting the data linkage, and the ESRI for making the HIPE data accessible. This study was funded by Sanofi. The sponsor had no involvement in the study design, in collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript and in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This work is published under the standard license to publish agreement. After 12 months the work will become freely available and the license terms will switch to a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License.

Rights and permissions

From twelve months after its original publication, this work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

de Camargo Cancela, M., Comber, H. & Sharp, L. Age remains the major predictor of curative treatment non-receipt for localised prostate cancer: a population-based study. Br J Cancer 109, 272–279 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2013.268

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2013.268

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Extreme hypofractionated stereotactic radiotherapy for elderly prostate cancer patients: side effects preliminary analysis of a phase II trial

La radiologia medica (2023)

-

Moderate hypofractionated helical tomotherapy for prostate cancer in a cohort of older patients: a mono-institutional report of toxicity and clinical outcomes

Aging Clinical and Experimental Research (2020)

-

Active Surveillance beim Prostatakarzinom

best practice onkologie (2019)

-

Active Surveillance beim Prostatakarzinom

Der Urologe (2019)

-

Impact of comorbidities at diagnosis on prostate cancer treatment and survival

Journal of Cancer Research and Clinical Oncology (2018)