Abstract

Background:

As research on quality of life of colorectal cancer (CRC) survivors has mainly focused on downsides of cancer survivorship, the aim of this study is to investigate benefit finding (BF) and post-traumatic growth (PTG) in long-term CRC survivors.

Methods:

Benefit finding, PTG, and quality of life were assessed 5 years after diagnosis in a population-based cohort of 483 CRC patients using the benefit finding scale, the post-traumatic growth inventory, and the EORTC QLQ-C30. Prevalence of BF and PTG, determinants of moderate-to-high BF and PTG, and the association between BF, PTG, and quality of life were investigated.

Results:

Moderate to high levels of BF and PTG were experienced by 64% and 46% of the survivors, respectively. Survivors with the highest level of education and with higher depression scores reported less BF and PTG. The PTG increased with increasing stage and self-reported burden of diagnosis. Quality of life only correlated weakly with PTG (Pearson's r=0.1180, P=0.0112) and not with BF (r=0.0537, P=0.2456).

Conclusion:

Many long-term CRC survivors experience BF and PTG. As these constructs were not strongly correlated with quality of life, focusing solely on quality of life after cancer misses an important aspect of survivorship.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is one of the most common malignant diseases worldwide. As prognosis of CRC has improved over the last years (Verdecchia et al, 2007), research on quality of life of CRC survivors has become increasingly important. This research has mainly focused on the negative experiences of cancer survivors like long-term symptoms and restrictions in quality of life (Jansen et al, 2010). But studies have shown that a high percentage of cancer survivors also report positive changes in the context of their disease (Dunn et al, 2006; Salsman et al, 2009; Rinaldis et al, 2010). Two constructs of positive consequences of cancer have been distinguished: post-traumatic growth (PTG) and benefit finding (BF). PTG refers to benefits associated with changes in life perspective, interpersonal relationship, and self-perception. The changes result from the struggle of an extreme event like a cancer diagnosis and treatment and cannot be caused by minor stressors (Tedeschi and Calhoun, 1995; Sumalla et al, 2009) . In contrast, BF is defined as the process in which the patient re-assigns positive value to the illness based on the benefits he or she identifies (Collins et al, 1990; Helgeson et al, 2006). While BF is hypothesised to start immediately after diagnosis, PTG refers to an active change in one's capacity to deal with adverse events and, thus, may develop even years after the cancer diagnosis (Calhoun and Tedeschi, 1998). Despite their distinct definitions, these terms have often been used interchangeably (Lechner et al, 2003; Mols et al, 2009; Sumalla et al, 2009).

Most previous studies on PTG and BF were based on samples including breast cancer or mixed cancer sites with assessments of PTG and BF in the first 2–3 years after diagnosis. Results from these studies have shown that around 80% of the survivors regard themselves as having benefited in some way from their cancer experience (Sumalla et al, 2009). Benefits were reported among others for life satisfaction/appreciation, relationship with others, and personal strength. Results on levels and determinants of BF and PTG were shown to be disease specific (Barskova and Oesterreich, 2009) and, thus, cannot be directly transferred to survivors of other cancers. Few studies investigated BF and PTG in CRC survivors (Dunn et al, 2006; Salsman et al, 2009; Rinaldis et al, 2010). However, these studies included short-term survivors only. To get further insight into PTG and BF in long-term CRC survivors, the aim of this paper is to investigate the prevalence of BF and PTG and to determine what socio-demographic, clinical, and psycho-social factors distinguish CRC patients who show a high level of BF and PTG from those who experience only low levels.

Materials and methods

Study design and study population

This analysis includes patients with CRC from a population-based case–control study (DACHS study) carried out in southwest Germany (Rhine-Neckar-Odenwald and Heilbronn Region). Further details about baseline recruitment in this study have been described elsewhere (Hoffmeister et al, 2009; Brenner et al, 2011).

In brief, patients who were mentally and physically able to participate in a personal interview of about 1 h were recruited by their clinicians, usually a few days after surgery. After an average of 3 years since diagnosis, detailed information on CRC treatment was collected from oncologists and other attending physicians in a standardised questionnaire. In 2009, a 5-year follow-up was conducted with 906 patients diagnosed in 2003 or 2004. After ascertainment of vital status and dates of death through population registries and after exclusion of patients who moved abroad (N=1) or with unknown new mailing address (N=1), a questionnaire was sent to all patients alive (N=585) who had not denied further contacts (N=584). Non-responders were mailed up to two reminder letters, which were followed by one reminder phone call in case of non-response to mailings. If patients rejected to return the questionnaire, a phone interview on the basis of a shortened version of the questionnaire (referred to as short questionnaire; details see below) was offered. Both questionnaires entailed questions concerning new concomitant diseases or recurrences of CRC. In case of reported new diagnoses including cancer recurrence, attending physicians were contacted to validate the diagnoses. Physicians were also contacted when information on CRC recurrence within 5 years after diagnosis was lacking or uncertain.

All participants gave written informed consent. The study was approved by the ethics committees of the University of Heidelberg and the state medical boards of Baden-Wuerttemberg and Rhineland-Palatinate.

Follow-up questionnaire

Benefit finding was assessed with the short form of the benefit finding scale (BFS; Antoni et al, 2001; Mohamed and Böhmer, 2004). The BFS has 10 items on a five-point Likert scale (Table 1) ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (extremely), which are summarised in four subscales (acceptance, sensitivity to others, improved coping, and new purpose of life) and a total BF. The PTG was measured by three scales (appreciation of life, new possibilities, and spiritual change) of the PTG inventory (Tedeschi and Calhoun, 1996; PTGI, Maercker and Langner, 2001). The PTGI scale ‘personal strength’ was not included, as the factor structure was not replicable in the German version (Maercker and Langner, 2001). The scale ‘relationship to others’ was excluded to avoid redundancies with other instruments and to reduce the overall length of the questionnaire. The implemented shortened version of the PTG entailed 10 items on a six-point Likert scale (Table 1) ranging from 0 (not at all) to 5 (to a very great degree). Quality of life was assessed with the Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 30 Items (QLQ-C30; Aaronson et al, 1993) developed by the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Psychological distress was assessed with the short form of the ‘questionnaire on stress in cancer patients revised version’ (QSC-R10; Herschbach et al, 2004). The 15-item short form of the geriatric depression scale (GDS) was included to assess depression (Yesavage et al, 1982; Gauggel and Birkner, 1999), as it was specifically developed for older persons and has been validated in cancer patients as well as older persons (Nelson et al, 2010). Additionally, the questionnaire included items to assess the identification as cancer patients (‘Do you still consider yourself as a cancer patient?’) and the self-reported burden of diagnosis and burden of treatment (‘How stressful were the following aspects of your colorectal cancer disease and treatment?’ – ‘initial diagnosis’, ‘treatment (chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and surgery)’).

A short questionnaire, which was used in case a patient was not willing to complete the full questionnaire, contained the global QLQ-C30 item as sole quality of life measure and some single questions on other domains but not on BF or PTG.

Statistical methods

The distribution of patient and disease characteristics was compared between responders, short-questionnaire responders, and non-responders to assess the potential impact of non-random missing data.

The scoring of the QLQ-C30, BFS, QSC-R10, and GDS was performed according to the scoring manuals. In case of missing items in the BFS or the QLQ-C30, multi-item scores were calculated as the mean of non-missing items if at least half of the items from the corresponding scale had been completed. The PTGI summary scores are usually computed as the sum of the item scores. In accordance with the BFS scoring, we calculated the mean of the PTGI item scores in order to handle missing items identically. In sensitivity analysis, we repeated the analyses using the sum instead of the mean of the item scores and the results were comparable.

Cutoff values defining the prevalence of BF or PTG (BF/PTG) were determined a priori (Table 1). In general, lower scores represent lower levels of BF and PTG. Prevalence of any BF/PTG was defined as checking more than the lowest item score (‘not at all’) at least once. Prevalence of moderate-to-high BF/PTG was defined by a mean score ⩾3, respectively.

Univariate logistic regression models were computed to estimate the association between the prevalence of moderate to high total BF/PTG and a priori defined potential determinants of BT/PTG:

-

Socio-demographic factors (sex, age at follow-up, partnership status at follow-up, highest school degree at baseline, number of real friends/relatives/family members at baseline).

-

Clinical factors (comorbidity at baseline, tumour stage, amount of adjuvant/neoadjuvant therapy (none, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy), CRC recurrence previous to follow-up).

-

Psycho-social factors (self-reported burden of diagnosis, self-reported burden of treatment, identification as cancer patient, psychological distress of cancer patients (QSC-R10), and depression score (GDS)).

In addition, multiple logistic regression models were computed to determine the independent association between each of the aforementioned factors and BF/PTG while controlling for all socio-demographic and clinical factors. We did not adjust for psycho-social factors to estimate the effect of clinical and socio-demographic factors independent of potential interdependencies of the outcomes with psycho-social factors. The analysis was repeated without dichotomising the BF and PTG scores using analysis of covariance.

The association between BF, PTG, and quality of life was estimated by Pearson's correlation coefficients. Furthermore, the mean functioning and global quality of life scores of survivors with moderate-to-high BF/PTG were compared with survivors with lower BF/PTG using a t-test and a multiple linear regression with adjustment for all factors that were significant in the analysis of determinants.

All analyses were performed with SAS software, version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Statistical significance was defined by a two-sided P<0.05. No multiple comparison corrections were made given the exploratory nature of the analysis.

Results

Of the 584 survivors in the 5-year follow-up, 23 were excluded from the survey, as they were physically or mentally not able to participate (e.g., because of dementia or hospitalisation), 19 did not respond to mailings and could not be contacted by phone, 12 agreed to participate, but did not return the questionnaire, and 21 actively refused to participate. The remaining patients returned a full (N=483) or short (N=25) questionnaire resulting in a response rate of 86% (full questionnaire) and 91% (full and short questionnaires), respectively.

Patient characteristics according to response status are shown in Table 2. At 5-year follow-up, mean age of survivors who returned a full questionnaire (full responders) was 72 years (standard deviation: 9 years). Of these survivors, 38% were female, 69% had completed 9 or fewer years of education, and 76% were living with a partner. The average time since diagnosis was 5.4 years (standard deviation: 0.4, range: 4.8–6.4 years). About 97% of the full responders had CRC stage I, II, or III at baseline (in almost equal shares), whereas only 3% had stage IV. The tumour had been located in the colon for 59% of these survivors, 98% had received surgery, and 58% had received any adjuvant or neoadjuvant treatment. A recurrence of CRC had occurred in 7%. Compared with non-responders including short-questionnaire responders, who were not included in the analysis, full responders were on average younger, more often male, had more often rectal cancer, and received more often adjuvant and/or neoadjuvant treatment. Overall quality of life was lower for short-questionnaire responders than for full responders, but the difference was not statistically significant (Δ=7.62, P=0.1209).

Prevalence of BF and PTG

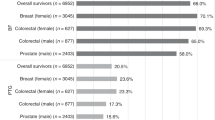

Almost all survivors experienced BF and PTG at least to some degree (Table 3) and more than half of the survivors reported moderate to high levels of total BF (64%) and of the subscales acceptance (62%), sensitivity to others (57%), improved coping (56%), and new purpose of live (53%). Moderate to high levels of PTG were reported by 46% of the survivors. While 70% of the survivors experienced moderate to high levels of appreciation of life, only 33% and 30% reported moderate to high levels for the subscales spiritual change and new possibilities.

Determinants of BF and PTG

The odds ratios (ORs) of the association between the potential determinants and the prevalence of moderate-to-high BF/PTG are presented in Table 4. Of the socio-demographic factors, only level of education was significantly associated with the prevalence of moderate-to-high BF. Survivors with higher education reported less often moderate to high levels of BF (after adjustment: PTrend=0.0088). For PTG, a similar but non-significant pattern was observed. Again, no other socio-demographic variable was significantly associated with moderate-to-high PTG, but older survivors tended to report less often PTG.

In the univariate analysis of clinical and psycho-social factors, the chance of experiencing moderate-to-high PTG increased significantly with the stage at diagnosis, the provision of chemotherapy, and the self-reported burden of diagnosis (Table 4). A similar but non-significant pattern was observed for the self-reported burden of treatment. After adjustment, only the association between burden of diagnosis and prevalence of moderate-to-high PTG remained significant (PTrend=0.0028). For BF, only the comparison between survivors reporting modest compared with high burden of diagnosis was significant. After adjustment, the chance to experience moderate-to-high BF was 41% lower for survivors reporting modest burden of diagnosis.

The distress level and the identification as a cancer patient 5 years after diagnosis were not associated with BF or PTG. The prevalence of high-to-moderate BF and PTG significantly decreased with the depression score 5 years after diagnosis (after adjustment, for BF: OR 0.91 (0.86–0.97), for PTG: OR 0.92 (0.86–0.98)).

Further in-depth analysis of the determinants of BF and PTG, where we used the original score as dependent variable, did not materially change the observed findings derived from using dichotomised PTG and BF scores (data not shown).

Association between BF, PTG, and quality of life

Total PTG and total BF were strongly correlated (Pearson's r=0.71). The correlation between quality of life and BF/PTG is shown in Table 5. Total BF and the domains of BF were not significantly correlated with global quality of life or any functioning score. Total PTG and the PTG domain ‘appreciation’ of life were significantly positively associated with global quality of life and physical functioning, but the correlations were small (all r<0.16). The PTG domain ‘new possibilities’ was significantly but weakly correlated with global quality of life (r=0.13), physical (r=0.13), and role functioning (r=0.10). Table 6 shows the mean quality of life scores according to the total PTG and BF levels. Only global quality of life was significantly associated with PTG. Mean global quality of life was 4.5 points lower for survivors who experienced lower PTG.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first population-based study examining BF and PTG in long-term CRC survivors. Five years after diagnosis, almost all CRC survivors experience BF or PTG at least to some degree with about half of them reporting moderate to high levels of BF and PTG. Domains with the highest prevalence of moderate to high growth were appreciation of life and acceptance.

Analysing determinants of BF and PTG may help to better understand these constructs and the factors that may influence the adjustment of cancer survivors to their disease. In our study, education was the only socio-demographic variable that was significantly associated with BF and PTG. In accordance with previous studies including short-term CRC survivors and mixed cancer samples (Widows et al, 2005; Jaarsma et al, 2006; Rinaldis et al, 2010), respectively, survivors with a higher level of education experienced less BF and PTG. Interpreting lower education as a proxy of lower socioeconomic status, one explanation for this finding may be that survivors with a lower socioeconomic status may routinely be confronted with hardships in their lives and, thus, may be more experienced in finding something positive from negative events (Tomich and Helgeson, 2004; Rinaldis et al, 2010).

In contrast to our study, which did not show a significant association between BF/PTG and age, studies that included survivors with various cancer sites reported that younger survivors experience more BF/PTG than older survivors (Gotay and Muraoka, 1998; Lechner et al, 2003; Morris et al, 2007). For long-term breast cancer survivors, one study on BF/PTG found a significant association between age and the PTG domain ‘new possibilities’ only (Mols et al, 2009), whereas another study on PTG did not find any significant association between age and PTG (Lelorain et al, 2010). The lack of a strong association between BF/PTG and age in our study might reflect the presumably narrower age range of our study that included CRC survivors only as compared with studies encompassing survivors with various cancer sites. Likewise, it might reflect an attenuation of age-specific differences over the long run as previous studies that reported consistent age effects included short-term survivors only.

Post-traumatic growth is thought to develop as a consequence of the struggle from the cancer diagnosis and treatment. Thus, the amount of perceived growth was hypothesised to be associated with the real or perceived life threat of the traumatic event (Tedeschi and Calhoun, 2004). In our study, the prevalence of moderate-to-high PTG was higher for survivors who had a higher objective burden of their disease, such as a higher stage at diagnosis or higher intensity of therapy, or a higher self-reported burden of diagnosis. In accordance with our results, previous studies in other cancer sites showed associations with perceived life threat (Lechner et al, 2003; Sears et al, 2003; Lelorain et al, 2010), severity of disease (Tomich and Helgeson, 2004; Urcuyo et al, 2005), and chemotherapy (Bower et al, 2005; Lelorain et al, 2010). For BF, we did not find such a consistent association with burden of disease. It has been reported that the association between BF and stage may be curvilinear, as cancer survivors with stage II had higher BF than survivors with stage I and IV (Lechner et al, 2003), but our results do not support this pattern.

While psychological distress during follow-up was not associated with BF or PTG, the prevalence of moderate-to-high BF and PTG was lower for survivors with higher depression scores at follow-up. Results from other studies on the association between depression and BF (Antoni et al, 2001; Urcuyo et al, 2005) and PTG (Cordova et al, 2001; Salsman et al, 2009) including breast cancer or short-term CRC survivors are inconsistent.

Overall, determinants of BF and PTG were found to be different, especially with respect to the association with stage, therapy, and burden of disease. Nonetheless, BF measured by the BFS and PTG measured by three subscales of the PTGI were strongly correlated. This result suggests that BF and PTG are related but independent constructs and the terms should be clearly defined and not used interchangeably.

In accordance with results from studies on other cancer sites (Cordova et al, 2001; Tomich and Helgeson, 2002; Mols et al, 2009), BF and PTG did not correlate with quality of life in long-term CRC survivors in our study. Survivors who experienced moderate-to-high PTG reported significantly higher mean global quality of life. However, the marginal size of the effect is unlikely to be clinically relevant (Osoba et al, 1998). We also did not find any non-linear associations, as was previously reported by Lechner et al (2006). As the EORTC QLQ-C30 measures specifically health-related quality of life, we additionally computed the correlation between BF/PTG and the single item on overall quality of life included in our questionnaire. The results were comparable to the result on the domain ‘quality of life’, which includes this single item together with an item on overall health. Thus, we did not find a meaningful association between BF/PTG and overall quality of life either. Due to this independence of quality of life and BF/PTG, the generally reported high global quality of life of long-term CRC survivors (Jansen et al, 2010) cannot be explained by the experience of BF and PTG. In addition, both positive and negative consequences of cancer survivorship must be investigated to get a comprehensive understanding of the adjustment of cancer patients to their disease.

A caveat to be considered in the interpretation of our study is that the PTGI was not directly developed to assess PTG in CRC survivors. Also, validation studies were based on college students (Tedeschi and Calhoun, 1996) and breast cancer patient samples (Brunet et al, 2010). The BFS was developed to assess BF in breast cancer patients (Antoni et al, 2001), but the German version was validated on a mixed cancer sample including mainly CRC patients (Mohamed and Böhmer, 2004). Thus, the BFS factor structure has been replicated in this survivor group. But due to the general focus on other cancer sites, the instruments assessing BF and PTG may miss important domains of growth that specifically arise for CRC patients, which are on average older and more often male. However, the high prevalence of BF and PTG in our study sample suggests that the assessed domains also apply to long-term CRC survivors.

A further caveat of the study is the restriction to three of the five domains of PTG. We decided to exclude the PTGI scale ‘personal strength’, as the factor structure was not replicable in the German version (Maercker and Langner, 2001). To avoid redundancies and to restrict the length of the questionnaire, the scale ‘relationship to others’ was additionally excluded. As a consequence, our assessment may miss some specific aspects of PTG. In addition, our estimates for total PTG may not be comparable to estimates from other studies that included the complete PTGI.

Strengths of our study are the population-based design, the high response rate, and the concurrent assessment of negative and positive consequences of disease and treatment with validated instruments.

In conclusion, our results show that BF and PTG are highly prevalent among long-term CRC survivors. Thus, to get a comprehensive understanding of the adjustment of cancer patients after diagnosis, negative as well as positive consequences of cancer survivorship need to be investigated. Quality of life was only weakly related to BF and PTG and, thus, the generally reported high global long-term quality of life after cancer cannot be directly explained by positive adjustments.

Change history

29 March 2012

This paper was modified 12 months after initial publication to switch to Creative Commons licence terms, as noted at publication

References

Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, Bullinger M, Cull A, Duez NJ, Filiberti A, Flechtner H, Fleishman SB, Haes JCJM, Kaasa S, Klee M, Osoba D, Razavi D, Rofe PB, Schraub S, Sneeuw K, Sullivan M, Takeda F (1993) The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst 85 (5): 365–376

Antoni MH, Lehman JM, Kilbourn KM, Boyers AE, Culver JL, Alferi SM, Yount SE, McGregor BA, Arena PL, Harris SD, Price AA, Carver CS (2001) Cognitive-behavioral stress management intervention decreases the prevalence of depression and enhances benefit finding among women under treatment for early-stage breast cancer. Health Psychol 20 (1): 20–32

Barskova T, Oesterreich R (2009) Post-traumatic growth in people living with a serious medical condition and its relations to physical and mental health: a systematic review. Disabil Rehabil 31 (21): 1709–1733

Bower JE, Meyerowitz BE, Desmond KA, Bernaards CA, Rowland JH, Ganz PA (2005) Perceptions of positive meaning and vulnerability following breast cancer: predictors and outcomes among long-term breast cancer survivors. Ann Behav Med 29 (3): 236–245

Brenner H, Chang-Claude J, Seiler CM, Rickert A, Hoffmeister M (2011) Protection from colorectal cancer after colonoscopy: a population-based, case-control study. Ann Intern Med 154 (1): 22–30

Brunet J, McDonough MH, Hadd V, Crocker PR, Sabiston CM (2010) The Posttraumatic Growth Inventory: an examination of the factor structure and invariance among breast cancer survivors. Psychooncology 19 (8): 830–838

Calhoun LG, Tedeschi RG (1998) Post-traumatic growth: future directions. In: Posttraumatic Growth: Positive Changes in the Aftermath of Crisis Tedeschi RG, Park CL, Calhoun LG (eds), pp 215–238. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwaj, NJ

Collins RL, Taylor SE, Skokan LA (1990) A better world or a shattered vision? Changes in life perspective following victimization. Social Cognition 8: 263–285

Cordova MJ, Cunningham LL, Carlson CR, Andrykowski MA (2001) Posttraumatic growth following breast cancer: a controlled comparison study. Health Psychol 20 (3): 176–185

Dunn J, Lynch B, Rinaldis M, Pakenham K, McPherson L, Owen N, Leggett B, Newman B, Aitken J (2006) Dimensions of quality of life and psychosocial variables most salient to colorectal cancer patients. Psychooncology 15 (1): 20–30

Gauggel S, Birkner B (1999) Validität und Reliabilität einer deutschen Version der Geriatrischen Depressionsskala. Z Kl Psych Psychoth 28 (1): 18–27

Gotay CC, Muraoka MY (1998) Quality of life in long-term survivors of adult-onset cancers. J Natl Cancer Inst 90 (9): 656–667

Helgeson VS, Reynolds KA, Tomich PL (2006) A meta-analytic review of benefit finding and growth. J Consult Clin Psychol 74 (5): 797–816

Herschbach P, Keller M, Knight L, Brandl T, Huber B, Henrich G, Marten-Mittag B (2004) Psychological problems of cancer patients: a cancer distress screening with a cancer-specific questionnaire. Br J Cancer 91 (3): 504–511

Hoffmeister M, Raum E, Krtschil A, Chang-Claude J, Brenner H (2009) No evidence for variation in colorectal cancer risk associated with different types of postmenopausal hormone therapy. Clin Pharmacol Ther 86 (4): 416–424

Jaarsma TA, Pool G, Sanderman R, Ranchor AV (2006) Psychometric properties of the Dutch version of the posttraumatic growth inventory among cancer patients. Psychooncology 15 (10): 911–920

Jansen L, Koch L, Brenner H, Arndt V (2010) Quality of life among long-term (>= 5 years) colorectal cancer survivors - systematic review. Eur J Cancer 46 (16): 2879–2888

Lechner SC, Carver CS, Antoni MH, Weaver KE, Phillips KM (2006) Curvilinear associations between benefit finding and psychosocial adjustment to breast cancer. J Consult Clin Psychol 74 (5): 828–840

Lechner SC, Zakowski SG, Antoni MH, Greenhawt M, Block K, Block P (2003) Do sociodemographic and disease-related variables influence benefit-finding in cancer patients? Psychooncology 12 (5): 491–499

Lelorain S, Bonnaud-Antignac A, Florin A (2010) Long term posttraumatic growth after breast cancer: prevalence, predictors and relationships with psychological health. J Clin Psychol Med Settings 17 (1): 14–22

Maercker A, Langner R (2001) Persönliche Reifung (Personal Growth) durch Belastungen und Trauma: Validierung zweier deutschsprachiger Fragebogenversionen. Diagnostica 47: 153–162

Mohamed NE, Böhmer S (2004) Die deutsche Version der Benefit Finding Skala: Ihre psychometrischen Eigenschaften bei Tumorpatienten. Z Med Psychol 13: 85–91

Mols F, Vingerhoets AJ, Coebergh JW, van de Poll-Franse LV (2009) Well-being, posttraumatic growth and benefit finding in long-term breast cancer survivors. Psychol Health 24 (5): 583–595

Morris BA, Shakespeare-Finch J, Scott JL (2007) Coping processes and dimensions of post-traumatic growth. Australas J Disaster Trauma Stud 1: 1–10

Nelson CJ, Cho C, Berk AR, Holland J, Roth AJ (2010) Are gold standard depression measures appropriate for use in geriatric cancer patients? A systematic evaluation of self-report depression instruments used with geriatric, cancer, and geriatric cancer samples. J Clin Oncol 28 (2): 348–356

Osoba D, Rodrigues G, Myles J, Zee B, Pater J (1998) Interpreting the significance of changes in health-related quality-of-life scores. J Clin Oncol 16 (1): 139–144

Rinaldis M, Pakenham KI, Lynch BM (2010) Relationships between quality of life and finding benefits in a diagnosis of colorectal cancer. Br J Psychol 101 (Pt 2): 259–275

Salsman JM, Segerstrom SC, Brechting EH, Carlson CR, Andrykowski MA (2009) Posttraumatic growth and PTSD symptomatology among colorectal cancer survivors: a 3-month longitudinal examination of cognitive processing. Psychooncology 18 (1): 30–41

Sears SR, Stanton AL, Danoff-Burg S (2003) The yellow brick road and the emerald city: benefit finding, positive reappraisal coping and posttraumatic growth in women with early-stage breast cancer. Health Psychol 22 (5): 487–497

Sumalla EC, Ochoa C, Blanco I (2009) Posttraumatic growth in cancer: reality or illusion? Clin Psychol Rev 29 (1): 24–33

Tedeschi R, Calhoun LG (1995) Trauma and Transformation: Growing in the Aftermath of Suffering. Sage Publications: CA, USA

Tedeschi RG, Calhoun LG (1996) The posttraumatic growth inventory: measuring the positive legacy of trauma. J Trauma Stress 9 (3): 455–471

Tedeschi RG, Calhoun LG (2004) Posttraumatic growth: conceptual foundations and empirical evidence. Psychol Inq 15 (1): 1–18

Tomich PL, Helgeson VS (2002) Five years later: a cross-sectional comparison of breast cancer survivors with healthy women. Psychooncology 11 (2): 154–169

Tomich PL, Helgeson VS (2004) Is finding something good in the bad always good? Benefit finding among women with breast cancer. Health Psychol 23 (1): 16–23

Urcuyo KR, Boyers AE, Carver CS, Antoni MH (2005) Finding benefit in breast cancer: relations with personality, coping, and concurrent well-being. Psychol Health 20 (2): 175–192

Verdecchia A, Francisci S, Brenner H, Gatta G, Micheli A, Mangone L, Kunkler I (2007) Recent cancer survival in Europe: a 2000-02 period analysis of EUROCARE-4 data. Lancet Oncol 8 (9): 784–796

Widows MR, Jacobsen PB, Booth-Jones M, Fields KK (2005) Predictors of posttraumatic growth following bone marrow transplantation for cancer. Health Psychol 24 (3): 266–273

Yesavage JA, Brink TL, Rose TL, Lum O, Huang V, Adey M, Leirer VO (1982) Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: a preliminary report. J Psychiatr Res 17 (1): 37–49

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Ute Handte-Daub and Petra Bächer for their excellent technical assistance. They are grateful to the study participants, the interviewers who collected the baseline data, and the following hospitals and cooperating institutions that recruited patients for this study: Chirurgische Universitätsklinik Heidelberg, Klinik am Gesundbrunnen Heilbronn, St Vincentiuskrankenhaus Speyer, St Josefskrankenhaus Heidelberg, Chirurgische Universitätsklinik Mannheim, Diakonissenkrankenhaus Speyer, Krankenhaus Salem Heidelberg, Kreiskrankenhaus Schwetzingen, St Marien und St Annastiftkrankenhaus Ludwigshafen, Klinikum Ludwigshafen, Stadtklinik Frankenthal, Diakoniekrankenhaus Mannheim, Kreiskrankenhaus Sinsheim, Klinikum am Plattenwald Bad Friedrichshall, Kreiskrankenhaus Weinheim, Kreiskrankenhaus Eberbach, Kreiskrankenhaus Buchen, Kreiskrankenhaus Mosbach, Enddarmzentrum Mannheim, and Kreiskrankenhaus Brackenheim. This work was supported by the German Research Council (grant numbers: BR 1704/6-1, BR 1704/6-3, BR 1704/6-4, and CH 117/1-1) and the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (grant numbers: 01KH0404 and 01ER0814).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This work is published under the standard license to publish agreement. After 12 months the work will become freely available and the license terms will switch to a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License.

Rights and permissions

From twelve months after its original publication, this work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Jansen, L., Hoffmeister, M., Chang-Claude, J. et al. Benefit finding and post-traumatic growth in long-term colorectal cancer survivors: prevalence, determinants, and associations with quality of life. Br J Cancer 105, 1158–1165 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2011.335

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2011.335

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Benefit finding in men affected by prostate cancer prior to and following radical prostatectomy – a cross-sectional study with a stratified sample

BMC Cancer (2023)

-

Factors impacting posttraumatic growth in head-and-neck cancer patients with oncologic emergencies

Supportive Care in Cancer (2022)

-

Quality of life, distress, and posttraumatic growth 5 years after colorectal cancer diagnosis according to history of inpatient rehabilitation

Journal of Cancer Research and Clinical Oncology (2022)

-

Post-traumatic growth 5 years after cancer: identification of associated actionable factors

Supportive Care in Cancer (2022)

-

Post-traumatic Growth in Cancer Patients: A Correlational Study in Turkey

Journal of Religion and Health (2022)