Abstract

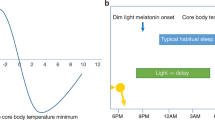

Biological circadian clocks oscillate with an approximately 24-hour period, are ubiquitous, and presumably confer a selective advantage by anticipating the transitions between day and night. The circadian rhythms of sleep, melatonin secretion and body core temperature are thought to be generated by the suprachiasmatic nucleus of the hypothalamus, the anatomic locus of the mammalian circadian clock1,2. Autosomal semi-dominant mutations in rodents with fast or slow biological clocks (that is, short or long endogenous period lengths; τ) are associated with phase-advanced or delayed sleep–wake rhythms, respectively. These models predict the existence of familial human circadian rhythm variants3,4 but none of the human circadian rhythm disorders are known to have a familial tendency5. Although a slight 'morning lark' tendency is common, individuals with a large and disabling sleep phase-advance are rare. This disorder, advanced sleep-phase syndrome, is characterized by very early sleep onset and offset; only two cases are reported in young adults6,7. Here we describe three kindreds with a profound phase advance of the sleep–wake, melatonin and temperature rhythms associated with a very short τ. The trait segregates as an autosomal dominant with high penetrance. These kindreds represent a well-characterized familial circadian rhythm variant in humans and provide a unique opportunity for genetic analysis of human circadian physiology.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$209.00 per year

only $17.42 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Shanahan, T.L. & Czeisler, C.A. Light exposure induces equivalent phase shifts of the endogenous circadian rhythms of circulating plasma melatonin and core body temperature in men. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 73, 27–35 (1991).

Czeisler, C.A., Weitzman, E., Moore-Ede, M.C., Zimmerman, J.C. & Knauer, R.S. Human sleep: its duration and organization depend on its circadian phase. Science 210, 1264–1267 (1980).

Ralph, M.R. & Menaker, M. A mutation of the circadian system in golden hamsters. Science 241, 1225– 1227 (1988).

Vitaterna, M.H. et al. Mutagenesis and mapping of a mouse gene, Clock, essential for circadian behavior. Science 264, 719 –725 (1994).

American Sleep Disorders Association in International Classification of Sleep Disorders: (Revised): Diagnostic and Coding Manual (Chairman, Thorphy, M.J.) 133– 136 (Rochester, Minnesota,1997).

Billiard, M. et al. A case of advanced-sleep phase syndrome. Sleep Res. 22, 109 (1993).

Singer, C.M. & Lewy, A.J. Case report: Use of the dim light melatonin onset in the treatment of ASPS with bright light. Sleep Res. 18, 445 (1989).

Horne, J.A. & Östberg, O. A self-assessment questionnaire to determine morningness- eveningness in human circadian rhythms. Int. J. Chronobiol. 4, 97–110 (1976).

Beck, A.T. The Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II) 1–2 (Harcourt Brace & Company, San Antonio, Texas, 1978).

Keenan, S.A. in Sleep Disorders Medicine: Basic Science, Technical Considerations and Clinical Aspects (ed. Chockroverty S) 79–94 (Butterworth-Heinemann, Boston, 1994).

Rechtschaffen, A. & Kales, A. in A Manual of Standardized Terminology, Techniques and Scoring System for Sleep Stages of Human Subjects (eds. Rechtschaffen, A. & Kales, A.) 1–12 (UCLA Brain Information Service/Brain Research Institute, Los Angeles, 1968).

Carskadon, M.A. et al. Guidelines for the multiple sleep latency test (MSLT): a standard measure of sleepiness. Sleep 9, 519– 524 (1986).

Lewy, A.J. & Sack, R.L. The dim light melatonin onset as a marker for circadian phase position. Chronobiol. Int. 6, 93–102 (1989).

Campbell, S.S., Dawson, D. & Zulley, J. When the human circadian system is caught napping: evidence for endogenous rhythms close to 24 hours. Sleep 16, 638–640 (1993).

Carskadon, M.A. & Dement, W.C. Sleep studies on a 90-minute day. Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. 39, 145–155 (1975).

Lavie, P. Ultrashort sleep-waking schedule. III. 'Gates' and 'forbidden zones' for sleep. Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. 63, 414–425 (1986).

Greenwood, K.M. Long-term stability and psychometric properties of the composite scale of morningness. Ergonomics 37, 377– 383 (1994).

Campbell, S.S., Gillin, J.C., Kripke, D.F., Erikson, P. & Clopton, P. Gender differences in the circadian temperature rhythms of healthy elderly subjects: relationships to sleep quality. Sleep 12, 529–536 (1989 ).

Haimov, I. & Lavie, P. Circadian characteristics of sleep propensity function in healthy elderly: a comparison with young adults. Sleep 20, 294–300 ( 1997).

Drennan, M.D., Selby, J., Kripke, D.F., Kelsoe, J. & Gillin, J.C. Morningness/eveningness is heritable. Soc. Neurosci. Abstr. 18, 196 ( 1992).

Katzenberg, D. et al. A CLOCK polymorphism associated with human diurnal preference. Sleep 21, 569–576 (1998).

Klerman, E.B., Dijk, D.J., Kronauer, R.E. & Czeisler, C.A. Simulations of light effects on the human circadian pacemaker: implications for assessment of intrinsic period. Am. J. Physiol. 270, R271–282 (1996).

Duffy, J.F., Rimmer, D.W., Silva, E.J. & Czeisler, C.A. Correlation of intrinsic circadian period with morningness-eveningness in young men. Sleep 22, S92 ( 1999).

Darlington, T.K. et al. Closing the circadian loop: CLOCK-induced transcription of its own inhibitors per and tim. Science 280, 1599–1603 (1998).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank A.J. Lewy, who provided discussions and comments,and A. Dean and T. Schenkenberg for critical reading of this manuscript. This investigation was supported by NIH grant HL/HD 59596 (L.J.P.) and Public Health Service research grant M01-RR00064 from the National Center for Research Resources.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jones, C., Campbell, S., Zone, S. et al. Familial advanced sleep-phase syndrome: A short-period circadian rhythm variant in humans. Nat Med 5, 1062–1065 (1999). https://doi.org/10.1038/12502

Received:

Accepted:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/12502

This article is cited by

-

Deep sequencing of microRNAs reveals circadian-dependent microRNA expression in the eyestalks of the Chinese mitten crab Eriocheir sinensis

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

Genetics of circadian rhythms and sleep in human health and disease

Nature Reviews Genetics (2023)

-

Excess S-adenosylmethionine inhibits methylation via catabolism to adenine

Communications Biology (2022)

-

High-throughput measurement of fibroblast rhythms reveals genetic heritability of circadian phenotypes in diversity outbred mice and their founder strains

Scientific Reports (2021)

-

A Two-Step Model of Human Entrainment: A Quantitative Study of Circadian Period and Phase of Entrainment

Bulletin of Mathematical Biology (2021)