Abstract

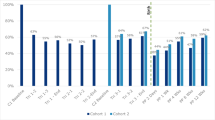

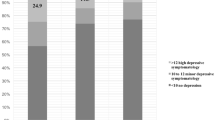

Objectives: The goals of this longitudinal study were to evaluate 1) the prevalence and stability of high depressive symptom levels during the first 18 months postpartum in a sample of otherwise healthy Black mothers varying in socio-economic status and 2) the relation of socio-demographic variables and level of socio-demographic risk to maternal depressive symptom levels during this time period. Methods: Participants were 163 Black adult mothers of healthy, full-term infants. The level of mothers' depressive symptomatology was assessed at 2, 3, 6, 12, and 18 months postpartum using the Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression Scale (CES-D). Mothers provided socio-demographic information at each assessment. Univariate and bivariate analyses were used to analyze the data. Results: The percentage of mothers with an elevated CES-D score (16 or higher) at single visits ranged from 13.5 to 14.7%, and 35.0% had at least one elevated CES-D score by 18 months postpartum. CES-D total scores were significantly correlated across each pair of visits (mean r = 0.57, all p's < 0.0001), and average CES-D scores did not change significantly over time. Single marital status, low-income status, and more negative maternal perceptions of the adequacy of income for meeting familial needs were significantly related to higher maternal CES-D scores at each assessment (all p's < 0.05). Level of socio-demographic risk, as assessed with a composite risk score derived from these variables, was significantly related to higher average CES-D scores (averaged across visits) (p < 0.0001) and to a greater frequency of elevated CES-D scores (16 or higher) during the first 18 months postpartum (p = 0.0002). Conclusions: The prevalence and stability of high levels of maternal depressive symptomatology during the first 18 months postpartum in this sample of Black women are consistent with those reported in prior studies of community samples of mothers unselected for race. Mothers with higher socio-demographic risk profiles had higher levels of maternal depressive symptoms at each assessment point.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Weissman MM, Leaf, PJ, Tischler, GL, Blazer, DG. Affective disorders in five United States communities. Psychol Med 1988;18(1):141-153.

Boyd JH, Weissman MM, Thompson WD, Myers JK. Screening for depression in a community sample. Understanding the discrepancies between depression symptom and diagnostic scales. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1982;39:1195-1200.

Cooper PJ, Campbell EA, Day A, Kennerley H. Non-psychotic psychiatric disorder after childbirth: A prospective study of prevalence, incidence, course and nature. Br J Psychiatry 1988;152:799-806.

Murray L. The impact of postnatal depression on infant development. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 1992;33:543-561.

O'Hara MW, Swain AM. Rates and risk of postpartum depression: A meta-analysis. Int Rev Psychiatry 1996;8:37-54.

O'Hara MW, Zekoski EM, Phillips LH, Wright EJ. Controlled prospective study of postpartum mood disorders: Comparison of childbearing and nonchildbearing women. J Abnorm Psychol 1990;99:3-15.

Beck CT. Predictors of postpartum depression: An update. Nurs Res 2001;50(5):275-285.

O'Hara MW. The nature of postpartum depressive disorders. In: Murray L, Cooper PJ, editors. Postpartum depression and child development. New York: Guilford Press 1997: 3-35.

Gotlib IH, Whiffen V, Mount J, Milne K, Cordy N. Prevalence rates and demographic characteristics associated with depression in pregnancy and the postpartum. J Consult Clin Psychol 1989;57:269-274.

Cox JL, Murray D, Chapman G. A controlled study of the onset, duration, and prevalence of postnatal depression. Br J Psychiatry 1993;163:27-31.

Hobfoll SE, Ritter C, Lavin J, Hulsizer MR, Cameron RP. Depression prevalence and incidence among inner-city pregnant and postpartum women. J Consult Clin Psychol 1995;63:445-453.

Belle D. Poverty and women's mental health. American Psychologist 1990;45(3):385-389.

Warner R, Appleby L, Whitton A, Faragher B. Demographic and obstetric risk factors for postnatal psychiatric morbidity. Br J Psychiatry 1996;168(5):607-611.

Blazer D, Kessler R, McGonagle K, Swartz M. The prevalence and distribution of major depression in a national community sample: The National Comorbidity Survey. Am J Psychiatry 1994;151:979-986.

McLennan JD, Kotelchuck M, Cho H. Prevalence, persistence, and correlates of depressive symptoms in a national sample of mothers of toddlers. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2001;40:1316-1323.

Civic D, Holt VL. Maternal depressive symptoms and child behavior problems in a nationally representative normal birthweight sample. Matern Child Health 2000;4(4):215-221.

Colletta ND. At risk for depression: A study of young mothers. J Genet Psychol 1983;142:301-310.

Reis J. Correlates of depression according to maternal age. J Genet Psychol 1988;149:535-545.

Coiro MJ. Depressive symptoms among women receiving welfare. Women Health 2001;32(1-2):1-23.

Cummings EM, Davies PT. Maternal depression and child development. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 1994;35:73-112.

Downey G, Coyne JC. Children of depressed parents: An integrative review. Psychol Bull 1990;108:50-76.

Field T. Psychologically depressed parents. In: Bornstein MH, editor. Handbook of parenting, Vol 4: Applied and practical parenting. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum, 1995: 85-99.

Tronick EZ, Weinberg MK. Depressed mothers and infants: Failure to form dyadic states of consciousness. In: Cooper PJ, editor. Postpartum depression and child development. New York: Guilford Press 1997: 54-81.

Hammen C. Children of affectively ill parents. In: Steinhausen HC, Verhulst F, editors. Risks and outcomes in developmental psychopathology. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 1999: 38-53.

Kaslow NJ, Deering CG, Racusin GR. Depressed children and their families. Clin Psychol Rev 1994;14:35-59.

Teti DM, Gelfand DM, Pompa J. Depressed mothers' behavioral competence with their infants: Demographic and psychosocial correlates. Dev Psychopathol 1990;2:259-270.

Teti DM, Gelfand DM, Messinger DS, Isabella R. Maternal depression and the quality of early attachment: An examination of infants, preschoolers, and their mothers. Dev Psychol 1995;31:364-376.

Garcia Coll C, Lamberty G, Jenkins R, McAdoo HP, Crnic KA, Wasik BH, Garcia HV. An integrative model for the study of developmental competencies in minority children. Child Dev 1996;67:1891-1914.

Brennan PA, Hammen C, Andersen MJ, Bor W, Najman JM, Williams GM. Chronicity, severity, and timing of maternal depressive symptoms: Relationships with child outcomes at age 5. Dev Psychol 2000;36:759-766.

Keller MB, Beardslee W, Dorer DJ, Lavori PW, Samuelson H, Klerman R. Impact of severity and chronicity of parental affective illness on adaptive functioning and psychopathology in children. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1986;43:930-937.

Garcia Coll C. Ethnic minority parenting. In: Bornstein MH, editor. Handbook of parenting Vol. 2: Biology and ecology of parenting. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum, 1995: 189-209.

Graham S. "Most of the subjects were white and middle class": Trends in published research on African Americans in selected APA journals, 1970-1989. Am Psychol 1992;47(5):629-639.

National Center for Children in Poverty. Low-income children in the United States: A brief demographic profile. New York: Columbia University, 2002.

Corcoran M. Rags to rags: Poverty and mobility in the United States. Ann Rev Sociol 1995;21:237-267.

McLoyd VC, Wilson L. The strain of living poor: Parenting, social support, and child mental health. In: Huston AC, editor. Children in poverty: Child development and public policy, New York: Cambridge University Press, 1991: 105-135.

Huston AC, McLoyd VC, Garcia Coll C. Poverty and behavior: The case for multiple methods and levels of analysis. Dev Rev 1997;17:376-393.

Conger RD, Wallace LE, Sun Y, Simons RL, McLoyd VC, Brody GH. Economic pressure in African American families: A replication and extension of the Family Stress Model. Dev Psychol 2002;38:179-193.

Deal LW, Holt VL. Young maternal age and depressive symptoms: Results from the 1988 National Maternal and Infant Health Survey. Am J Public Health 1998;88(2):266-270.

NICHD Early Child Care Research Network. Chronicity of maternal depressive symptoms, maternal sensitivity, and child functioning at 36 months. Dev Psychol 1999;35:1297-1310.

Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. J Appl Psychol Meas 1977;1:385-401.

Campbell SB, Cohn JF, Flanagan C, Popper S, Meyers T. Course and correlates of postpartum depression during the transition to parenthood. Dev Psychopathol 1992;4:29-47.

Campbell SB, Cohn JF, Meyers T. Depression in first-time mothers: Mother-infant interaction and depression chronicity. Dev Psychol 1995;31:349-357.

Campbell SB, Cohn JF. The timing and chronicity of postpartum depression: Implications for infant development. In: Murray L, Cooper PJ, editors. Postpartum depression and child development. New York: Guilford Press, 1997.

Beeghly M, Weinberg MK, Olson KL, Kernan H, Riley J, Tronick E. Stability and change in level of maternal depressive symptomatology during the first postpartum year. J Affect Disord 2002;71:169-180.

Husaini BA, Neff DA, Harrington JB, Hughes MD, Segal D. Depression in rural communities. Validating the CES-D scale. J Community Psychol 1980;8:20-27.

Campbell SB, Cohn JF. Prevalence and correlates of postpartum depression in first-time mothers. J Abnorm Psychol 1991;100:594-599.

Weinberg MK, Tronick EZ, Beeghly M, Olson KL, Kernan H, Riley J. Subsyndromal depressive symptoms and major depression in postpartum women. Am J Orthopsychiatry 2001;71:87-97.

Derogatis LR, Spencer R. The brief symptom inventory: Administration, scoring, and procedure manual. Baltimore, MD: Clinical Psychometric Research, 1982.

Hollingshead A. Four-factor index of social status. New Haven, CT: Yale University, 1979.

Seifer R, Sameroff AJ, Dickstein S, Keitner G, Miller I, Rasmussen S, et al. Parental psychopathology, multiple contextual risks, and one-year outcomes in children. J Clin Child Psychol 1996;25:423-435.

Sameroff AJ, Seifer R, Baldwin A, Baldwin C. Stability of intelligence from preschool to adolescence: The influence of social and family risk factors. Child Dev 1993;64(1):80-97.

Judd LL, Martin PP, Wells KB, Rapaport MH. Socioeconomic burden of subsyndromal depressive symptoms and major depression in a sample of the general population. Am J Psychiatry 1996;153:1411-1417.

Judd LL, Akiskal HS, Zeller PJ, Paulus MP, Leon AC, Maser JD, et al. Psychosocial disability during the long-term course of unipolar major depressive disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2000;57:375-380.

Gotlib IH, Lewinsohn PM, Seeley JR. Symptoms versus a diagnosis of depression: Differences in psychosocial functioning. J Consult Clin Psychol 1995;63(1):90-100.

Scholle SH, Kelleher K. Preferences for depression advice among low-income women. Maternal Child Health 2003;7(2):95-102.

Kelly RH, Zatzick DF, Anders TF. The detection and treatment of psychiatric disorder and substance use among pregnant women cared for in obstetrics. Am J Psychiatry 2001;158(2):213-219.

Davidson J, Meltzer-Brody S. The underrecognition and undertreatment of depression: What is the breadth and depth of the problem? J Clin Psychiatry 1999;60:S4-S9.

England SJ, Ballard C, George S. Chronicity in postnatal depression. Eur J Psychiatry 1994;8:93-96.

Cicchetti D, Toth SL. The development of depression in children and adolescents. Am Psychologist 1998;53(2):221-241.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Beeghly, M., Olson, K.L., Weinberg, M.K. et al. Prevalence, Stability, and Socio-Demographic Correlates of Depressive Symptoms in Black Mothers During the First 18 Months Postpartum. Matern Child Health J 7, 157–168 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1025132320321

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1025132320321