Abstract

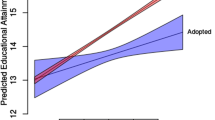

A model is presented for the truncated trivariate normal distribution that arises in behavior genetic adoption designs that focus on sibling similarity to estimate shared environmental effects. The model estimates the point of truncation and shared environmentality. Both moment and maximum likelihood estimates are obtained numerically. Simulations indicate that the model and the numerical procedures perform well when they are most needed, that is, when shared environmentality is large, truncation is extensive or both. When applied to published data from the Texas Adoption Project, results indicate that the point of truncation is at about the 63rd percentile of the family environmental quality distribution (i.e., the bottom 63% is missing) and shared environmentality is about 55%. Implications for current views on the importance of shared environment for child developmental outcomes such as antisocial behavior and IQ are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

REFERENCES

Aitken, A. C. (1934). Note on selection from a multivariate normal population. Proc. Edinburg Math. Soc. B 4:106-110.

Arnold, B. C., Beaver, R. J., Groenveld, R. A., and Meeker, W. Q. (1993). The nontruncated marginal of a truncated bivariate normal distribution. Psychometrika 58:471-488.

Baumrind, D. (1993). The average expectable environment is not good enough: A response to Scarr. Child Dev. 64:1299-1317.

Cadoret, R. J., Yates, W. R., Troughton, E., Woodworth, G., and Stewart, M. A. (1995). Genetic-environmental interaction in the genesis of aggressivity and conduct disorders. Arch. General Psychiatry 52:916-924.

Capaldi, D. M., and Patterson, G. R. (1991). Relation of parental transitions to boys' adjustment problems: I. A Linear hypothesis. II. Mothers at risk for transitions and unskilled parenting. Dev. Psychol. 27:489-504.

Carey, G. (1986). A general multivariate approach to linear modeling in human genetics. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 39:775-786.

Cohen, A. C. (1991). Truncated and Censored Samples: Theory and Applications, Marcel Dekker, New York.

Deater-Deckard, K., and Dodge, K. A. (1997). Externalizing behavior problems and discipline revisited: Nonlinear effects and variation by culture, context, and gender. Psychol. Inquiry 8:161-175.

DeFries, J. C., Plomin, R., and Fulker, D. (1994). Nature, Narture During Middle Childhood, Blackwell, Cambridge, MA. Eaves, L. J. (1988). Dominance alone is not enough. Behav. Genet. 18:27–33.

Grayson, D. A. (1989). Twins reared together: Minimizing shared environmental effects. Behav. Genet. 19:593-604.

Hart, B., and Risley, T. R. (1995). Meaningful Differences in the Everyday Experiences of Young American Children, Paul H. Brooks, Baltimore, MD.

Horn, J. M., Loehlin, J. C., and Willerman, L. (1979). Intellectual resemblance among adoptive and biological relatives: The Texas adoptive project. Behav. Genet. 9:177-201.

Lykken, D. T. (1995). The Antisocial Personalities, Erlbaum Associates, Hillsdale, NJ.

Lykken, D. T., Tellegen, A., and DeRubeis, R. (1978). Volunteer bias in twin research: The rule of two-thirds. Soc. Biol. 25(1):1-9.

Lykken, D. T., McGue, M., and Tellegen, A. (1987). Recruitment bias in twin research: The rule of two-thirds reconsidered. Behav. Genet. 17(4):343-362.

Martin, N. G., and Wilson, S. R. (1982). Bias in the estimation of heritability from truncated samples of twins. Behav. Genet. 12(4):467-472.

Miles, D. R., and Carey, G. (1997). Genetic and environmental architecture of human aggression. J. Person. Soc. Psychol. 72:207-217.

Neale, M. C., Eaves, L. J., Kendler, K. S., and Hewitt, J. K. (1989). Bias in correlations from selected samples of relatives: The effects of soft selection. Behav. Genet. 19(2):163-169.

Neale, M. C., and Cardon, L. R. (1992). Methodology for Genetic Studies of Twins and Families, Kluwer Academic, Boston.

Plomin, R., and DeFries, J. C. (1985). Origins of Individual Differences in Infancy, Academic Press, New York.

Plomin, R., Chipuer, H. M., and Neiderhiser, J. M. (1994a). Behavioral genetic evidence for the importance of nonshared environment. In Hetherington, E. M., Reiss, D., and Plomin, R. (eds.), Separate Social Worlds of Siblings: The Impact of Nonshared Environment on Development, Erlbaum Associates, Hillsdale, NJ, pp. 1-31.

Plomin, R., Reiss, D., Hetherington, E. M., and Howe, G. W. (1994b). Nature and nurture: Genetic contributions to measures of the family environment. Dev. Psychol. 30:32-43.

Rowe, D. C. (1994). The Limits of Family Influence: Genes, Experience, and Behavior, Guilford Press, New York.

Rowe, D. C. (1997). Are parents to blame? A look at The Antisocial Personalities. Psychol. Inquiry 8:251-260.

Scarr-Salapatek, S. (1971). Race, social class, and IQ. Science 174:1285-1295.

Scarr, S. (1992). Developmental theories for the 1990s: Development and individual differences. Child Dev. 63:1-19.

Scarr, S., and Weinberg, R. A. (1978). The influence of “family background” on intellectual attainment. Am. Sociol. Rev. 43(Oct.):674-692.

Statistical Sciences (1995). S-Plus Guide to Statistical and Mathematical Analysis, Version 3.3, StatSci, Seattle, WA.

Stoolmiller, M. (1997). Implications of the restricted range of family environments for estimates of heritability and nonshared environment in behavior genetic adoption studies (submitted).

Stoolmiller, M., Patterson, G. R., and Snyder, J. (1997). Parental discipline and child antisocial behavior: A contingency-based theory and some methodological refinements. Psychol. Inquiry 8:223-229.

Tanner, M. A. (1993). Tools for Statistical Inference: Methods for the Exploration of Posterior Distributions and Likelihood Functions, Springer-Verlag, New York.

Wilson, R. S. (1983). The Louisville twin study: Developmental synchronies in behavior. Child Dev. 54:298-316.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Stoolmiller, M. Correcting Estimates of Shared Environmental Variance for Range Restriction in Adoption Studies Using a Truncated Multivariate Normal Model. Behav Genet 28, 429–441 (1998). https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1021685211674

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1021685211674