“There is no such thing as an infant… without maternal care one would find no infant.”

– D.W. Winnicott (Reference Winnicott1960, p. 586)

Twenty percent of children ages 1–7 years meet diagnostic criteria for an emotional or behavioral disorder, including attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), oppositional defiant disorder, and sleep and feeding disorders (Vasileva, Graf, Reinelt, Petermann, & Petermann, Reference Vasileva, Graf, Reinelt, Petermann and Petermann2020). Despite this alarming figure, early life is relatively underrepresented in psychopathology research, particularly infancy, which is a period that is fundamental to the development of psychological disorders (Lyons-Ruth et al., Reference Lyons-Ruth, Todd Manly, Von Klitzing, Tamminen, Emde, Fitzgerald and Watanabe2017). Several factors likely explain the relative lack of attention to the mental health of infants and young children. At the most basic level is the challenge of assessment. For most disorders, diagnosis requires some information about the individual's subjective experience, but preverbal children have limited ability to communicate their experiences. More pernicious can be the lack of attention to infants and young children that may stem from cultural beliefs, perhaps subconsciously held, that infants and young children are fundamentally different in their humanity compared to adults (Lancy, Reference Lancy2014). In fact, mind perception research indicates that lay adults view infants as having limited capacity for “agency” (e.g., self-control, morality, thought) relative to older humans (Gray, Gray, & Wegner, Reference Gray, Gray and Wegner2007; Weisman, Dweck, & Markman, Reference Weisman, Dweck and Markman2017) – and beliefs of diminished capacities are associated with devaluing of others (Waytz, Gray, Epley, & Wegner, Reference Waytz, Gray, Epley and Wegner2010). Perhaps in response to long-standing barriers to the study of infant mental health, there are recurring calls to consider early life as an important period for identification and intervention in mental health and psychological disorder (e.g., recently, Wakschlag et al., Reference Wakschlag, Roberts, Flynn, Smith, Krogh-Jespersen, Kaat and Davis2019).

Developmental neuroscientists have demonstrated that the infant brain's dramatic plasticity renders it particularly susceptible to environmental adversity (Nelson & Gabard-Durnam, Reference Nelson and Gabard-Durnam2020), and have provided evidence that early life is uniquely important for understanding risk for psychopathology (Luby et al., Reference Luby, Allen, Estabrook, Pine, Rogers, Krogh-Jespersen and Wakschlag2019). In addition to protection from adversity, infants and young children require consistent, responsive care to meet their needs for healthy psychological functioning (Drury, Sánchez, & Gonzalez, Reference Drury, Sánchez and Gonzalez2016; Zeanah, Humphreys, Fox, & Nelson, Reference Zeanah, Humphreys, Fox and Nelson2017). By studying how variation in the early environment, including experiences of adversity and the quality of care, influences infant development, scientists may uncover the origins of psychological disorder. Such efforts, however, have been limited by traditional approaches focused on diagnostic nosology, which emphasizes characterizing and classifying symptoms into units or categories in order to understand disorders (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Nosological approaches are less useful in early life for several reasons. First, these approaches often rely on the ability of the individual to communicate their subjective experience; second, they usually focus solely on the internal processes of the individual, failing to consider environmental processes that shape behavior; finally, they do not consider broader socioemotional disturbances that are indicators of psychopathology in early life but that do not meet criteria for specific disorders (e.g., high negative emotionality; Kostyrka-Allchorne, Wass, & Sonuga-Barke, Reference Kostyrka-Allchorne, Wass and Sonuga-Barke2020).

The National Institute of Mental Health's (NIMH) Research Domain Criteria (RDoC) initiative (Cuthbert, Reference Cuthbert2014) offers an opportunity to conceptualize psychopathology in a way that emphasizes its dimensional nature, facilitating understanding of how psychopathology emerges in early life. Moreover, the dimension of the environment may be incorporated into this framework to understand the conditions under which psychopathology is more or less likely to develop. Given that infants’ and young children's environments are shaped most dramatically by their relationship with their primary caregiver(s), we argue for the importance of extending the RDoC framework to characterizing the relationships that infants and young children have with those who care for them as a means of operationalizing the early environment. In the present paper, we review evidence for the importance of caregiving relationships for children's mental health, describe how a specific RDoC domain (i.e., social processes) can be applied to examine the parent–child relationship across units of analysis, and consider how this approach can advance our understanding of risk and resilience processes in developmental psychopathology.

Caregiver Relationships are Foundational to Mental Health

The field of developmental psychopathology has long recognized that children develop in the context of their environment and that, particularly for infants and young children, their environment is almost entirely controlled by the child's caregivers (most often the child's parents, though we use the terms caregiver and parent interchangeably to refer to those who provide care for infants and young children). As an altricial species, human infants are completely reliant on those who care for them for their survival and growth. For these reasons, researchers and theorists in infant and early childhood mental health have centralized the caregiving relationship in attempting to understand variation in individuals’ early life functioning. As Winnicott indicates in the quotation that leads this article, without a caregiver there would be no infant – both literally because the infant would not survive and figuratively because it is impossible to understand the infant's functioning outside the context of their caregiving environment. While the presence of a caregiver is species expectant, the nature of children's experiences of their caregiving environment varies widely, or, in other words, is experience dependent (Greenough, Black, & Wallace, Reference Greenough, Black and Wallace1987). There is a substantial body of work linking variability in caregiving to children's functioning in multiple domains (Karreman, van Tuijl, van Aken, & Deković, Reference Karreman, van Tuijl, van Aken and Deković2006; Pinquart, Reference Pinquart2017; Sroufe, Reference Sroufe2005; Valcan, Davis, & Pino-Pasternak, Reference Valcan, Davis and Pino-Pasternak2018).

Theories of Caregiving and Child Mental Health

Theoretical models of the etiology of child psychopathology inevitably include parenting as either a direct or indirect effect (McKee, Jones, Forehand, & Cuellar, Reference McKee, Jones, Forehand and Cuellar2013). Some disorders explicitly require an external event or environment for their onset, and either are directly related to caregiving experiences (e.g., reactive attachment disorder; disinhibited social engagement disorder) or follow from traumatic events, which frequently involve the child's caregiver (e.g., posttraumatic stress disorder following maltreatment; Guyon-Harris, Humphreys, & Zeanah, Reference Guyon-Harris, Humphreys and Zeanah2020; Humphreys & Zeanah, Reference Humphreys and Zeanah2015). For disorders without explicitly outlined etiology, caregiving experiences such as maltreatment are highlighted as possible precipitants (e.g., for major depressive disorder; Humphreys et al., Reference Humphreys, LeMoult, Wear, Piersiak, Lee and Gotlib2020; LeMoult et al., Reference LeMoult, Humphreys, Tracy, Hoffmeister, Ip and Gotlib2020) or as contributing to onset and progression (e.g., oppositional defiant disorder, conduct disorder; Toth & Cicchetti, Reference Toth and Cicchetti2013).

Exactly how adverse caregiving experiences increases risk for psychopathology is an area of debate. Behaviorists may focus on dynamic interactive patterns between parents and their children, finding coercive cycles of caregiver–child behaviors that lead to psychological problems in children, such as high aggression (Patterson, Reference Patterson2004). Yet, a strict behavioral approach to characterizing the caregiver–child relationship omits other important characteristics of this relationship. What likely most influences child development is “not an interactive pattern itself, but rather what is communicated and experienced within that pattern about the caregiving relationship, the self, and the other” (Zeanah & Barton, Reference Zeanah and Barton1989, p. 136). Other perspectives, such as attachment theory, can be integrated with behavioral approaches to emphasize how the parent's working model of the child (i.e., their cognitive representation of the child) influences parent–child interactions (Stern, Reference Stern2018). In turn, an infant's experience with their caregiver may shape the development of the infant's mental representations of the self and relationships (Stern, Reference Stern2018), with implications for how that infant processes social information across the life span (Dykas & Cassidy, Reference Dykas and Cassidy2011). Because caregivers’ representations of who their child is and what their child's behaviors mean play an important role in determining the nature of the caregiver–child relationship, these implicit beliefs are a crucial aspect of assessment of the caregiver–child relationship and of determining its impact on children's risk for psychopathology.

Individual Differences in Caregivers’ Perceptions of and Behaviors Towards their Children

Given that caregivers' feelings and beliefs guide their behavior, it is important to consider individual differences in how caregivers perceive their children; these perceptions are sometimes referred to as caregivers' internal working models of their children. Although humans have internal working models for all of their social partners, it is worth considering whether there is something special, unique, or different about a parent's representation of their child, relative to representations of others in their social world. Compared to other species, humans are distinct in having caregiver–child attachments that are representation-based, culturally informed, exclusive, and long-term (Feldman, Reference Feldman2017). The level of motivation that human caregivers require to meet the needs of their children is so high that, if not well-calibrated, can result in feeling too little for the child (e.g., callous–unemotional caregiving), or feeling too much for the child (e.g., obsessive and hypervigilant caregiving; Swain, Lorberbaum, Kose, & Strathearn, Reference Swain, Lorberbaum, Kose and Strathearn2007). In fact, the processes that support the unique set of behaviors involved in caregiving have been theorized to be a pathway to psychopathology in parents, such that evolution-driven brain systems that promote caregiving behaviors can go awry in a manner that is associated with pathology (Swain et al., Reference Swain, Lorberbaum, Kose and Strathearn2007).

Relevant to the RDoC goal of understanding functioning “across the full range of human behavior from normal to abnormal” (NIMH, 2021), one problem for researchers is how to delineate normative patterns of caregivers’ representations of their children so that disturbances in these patterns can be clearly identified. Normative patterns appear to involve early intense interest in who the child is and what their needs are, as well as a positive bias towards one's own baby that is unique relative to other social partners. For example, many caregivers report highly elaborated working models of their child (even when interviewed before they have yet met [during gestation]; Dayton, Levendosky, Davidson, & Bogat, Reference Dayton, Levendosky, Davidson and Bogat2010), intense emotions and feelings of bond (e.g., caregivers often report a “preoccupation with the interests and wants” of the baby; Swain et al., Reference Swain, Lorberbaum, Kose and Strathearn2007), and great delight in their child (e.g., nearly three-quarters of mothers report thoughts of “perfection” about their 3–4 month-old infant; Leckman et al., Reference Leckman, Mayes, Feldman, Evans, King and Cohen1999). Positive feelings of bond toward infants (e.g., joy, love, protection) appear to increase across the first 6 months of the infant's life (Roth, Humphreys, King, Gotlib, & Robakis, Reference Roth, Humphreys, King, Gotlib and Robakis2021).

Nevertheless, divergent patterns in parents’ cognitive representations of children may be quite common. Almost half of parents in nonclinical samples have internal working models indicating either disengagement with their child (e.g., indifference to the child or enforced emotional distance) or distortion of their relationship with their child (e.g., self-involvement or role-reversal; Vreeswijk, Maas, & van Bakel, Reference Vreeswijk, Maas and van Bakel2012). Experiences such as miscarriage and stillbirth may influence caregivers’ internal working models in future pregnancies by leading to coping that minimizes the possibility of additional emotional distress (e.g., restraining excitement, avoiding talking about pregnancy, avoiding thinking about future child) (Lee, McKenzie-McHarg, & Horsch, Reference Lee, McKenzie-McHarg and Horsch2017). Competing goals may also explain individual differences in caregivers’ cognitive representations of their children. Parents are not merely caregivers to a single child, but have multiple social roles (e.g., professional, romantic partner, friend, sibling, child, and parent to other children) and are also responsible for their own wellbeing (Solomon & George, Reference Solomon and George1996). The best interest of the parent and best interest of a given child may, at times, be in conflict (Humphreys & Salo, Reference Humphreys and Salo2020; Trivers, Reference Trivers1974). Trade-offs are most apparent in scenarios where the survival of the child comes at a dramatic cost to the parent (Clutton-Brock, Reference Clutton-Brock1991; Jeffery & Scheper-Hughes, Reference Jeffery and Scheper-Hughes1989), though trade-offs regarding sensitive care and parent self-care are more commonplace (e.g., Perry et al., Reference Perry, Finegood, Braren, Dejoseph, Putrino, Wilson and Blair2019).

Because parents’ current and past experiences influence their cognitive representation of and relationship with a given child, the characteristics of one caregiver–child relationship should not be treated as trait-like within the caregiver. A specific caregiver will likely have different representations of their different children, and the characteristics of each relationship are dynamic, unfolding between the parent and specific child over time (Kochanska, Boldt, & Goffin, Reference Kochanska, Boldt and Goffin2019). Fortunately, the potential malleability of caregiving processes indicates opportunity for intervention based on research of when and how different caregivers and children would most benefit. In the following section, we propose that the RDoC social processes domain provides a useful framework to study the caregiver–child relationship at multiple levels of analysis in order to better characterize this relationship as an environmental context for children's development and to scrutinize its role in the etiology of psychopathology.

Caregiver–child Relationships in the RDoC Framework

The NIMH RDoC framework was introduced in response to limitations of existing classification systems for psychopathology (e.g., Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders [DSM] and International Classification of Diseases [ICD]), including high comorbidity of disorders, heterogeneity within disorders, and binary cut-points that conceal the dimensional nature of symptoms (Cuthbert & Insel, Reference Cuthbert and Insel2013). Instead of focusing on pre-existing classification systems, RDoC's goal was to focus research on “circuit-based behavioral dimensions” that cut across diagnostic categories in order to determine the full range of normative to atypical functioning and to identify core components of psychopathology (Cuthbert, Reference Cuthbert2014). Ultimately, by integrating these core components, RDoC aims to advance understanding of the etiology of psychopathology and inform more personalized approaches to intervention.

RDoC has led to dramatic changes in conceptualizations of adult psychopathology, including consideration of transdiagnostic processes and integration of multiple levels of analysis (e.g., genetic, neural, physiological, and behavioral) (Sanislow, Reference Sanislow2020). Of course, given that the environment influences both immediate and long-term psychobiological functioning and the expression and impact of genes, none of these levels of analysis can be fully understood without considering an individual's environment. RDoC recognizes environmental factors as key contributing processes to the development of psychopathology, conceptualizing each domain of human functioning as situated within and affected by the environmental context (NIMH, 2021). Of note, however, while the RDoC matrix currently informs how researchers can organize each domain of human functioning into subconstructs and measures, it does not provide specific guidance regarding how to organize, define, and operationalize the environment and its interaction with development (Mittal & Wakschlag, Reference Mittal and Wakschlag2017). Importantly, conceptualizing and measuring the naturalistic environment is at least as complex as analyzing the neural circuitry underlying human behavior.

As it currently stands, the RDoC framework risks considering the environment as a feature that exists outside the matrix of core components of psychological disorders. Critically, the RDoC framework was intended to evolve in order to incorporate advancing knowledge, and other scientists recognize the need to better integrate and expand on environmental and developmental processes within the framework (Garber & Bradshaw, Reference Garber and Bradshaw2020; Mittal & Wakschlag, Reference Mittal and Wakschlag2017; Sanislow, Reference Sanislow2020). Not only is the environment multidimensional and dynamic, but, especially during early life, it is largely determined by relationships with close others (King & Osofsky, Reference King, Osofsky, Osofsky and McAlister Groves2018). Logically, therefore, if one must understand circuit-based behavioral dimensions within the context of the environment, one must similarly understand these dimensions as situated in and affected by relationships.

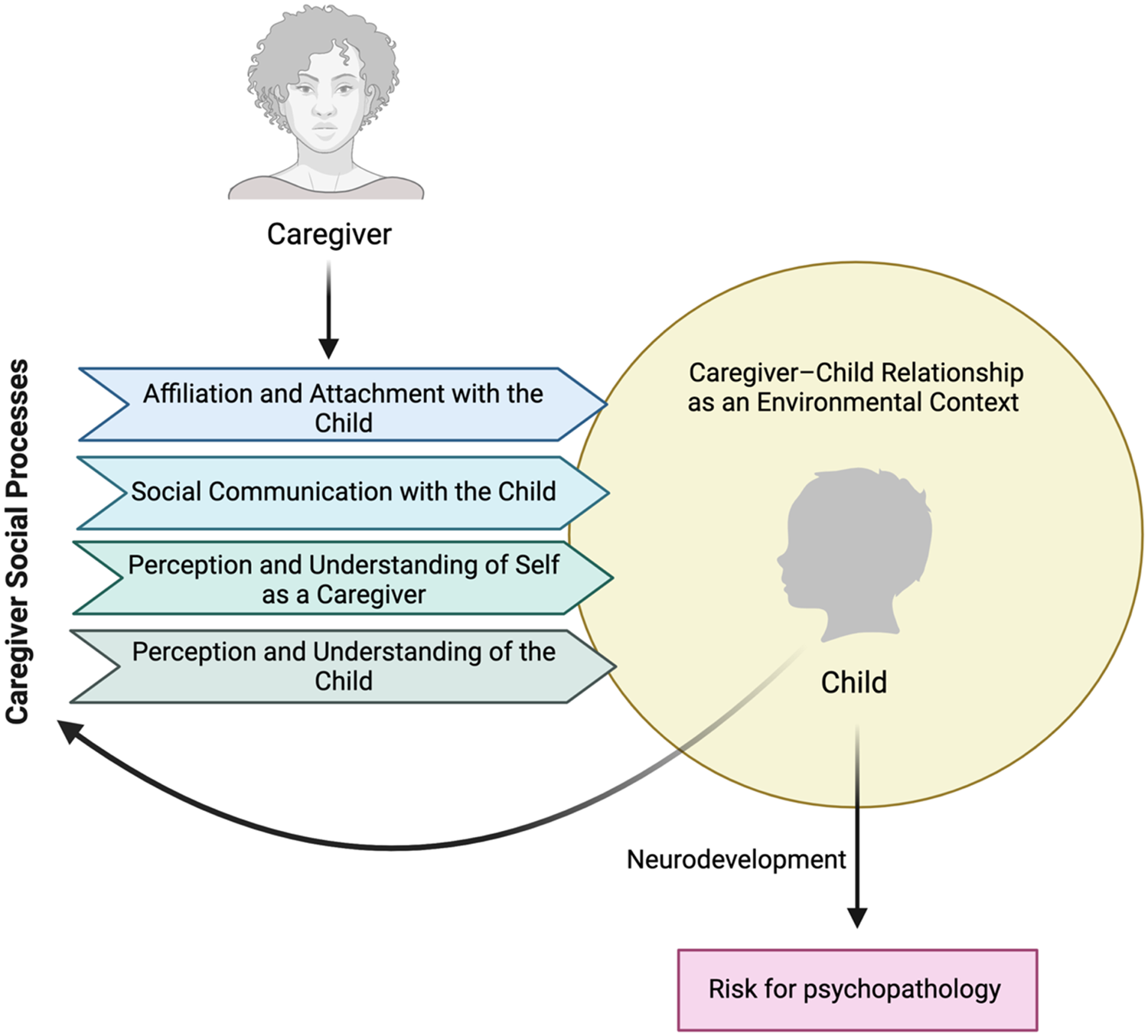

The tension between the traditional theoretical approach of research in developmental psychopathology emphasizing dynamic individual–environment transactions across development, and RDoC's focus on intrinsic dimensions of functioning has already been well articulated (Garber & Bradshaw, Reference Garber and Bradshaw2020). Some researchers have suggested ways to address interpersonal aspects of the environment by including macro-level units that account for the nesting of individuals within families and communities (Shankman & Gorka, Reference Shankman and Gorka2015). Here, we propose that aspects of the early environment that are determined through relationships with caregivers could usefully be conceptualized within the RDoC matrix. Specifically, we argue that the RDoC social processes domain could be used as a basis to evaluate variability in specific dimensions of the caregiver–child relationship across levels of analysis by measuring processes that mediate caregivers’ thoughts, feelings, and behaviors with a specific child, and ultimately the nature of that child's early environment. Notably, a focus on conceptualizing the caregiver–child relationship using the social processes domain involves an expanded understanding of core dimensions of human functioning as properties that not only influence a single individual (e.g., the caregiver) but that shape the environmental context of close others who depend on that individual (e.g., the infant/young child). In Figure 1, we depict this theoretical framework, visualizing the influence of caregivers’ social processes on the child's environment, and, in turn, on the child's neurodevelopment and risk for psychopathology.

Figure 1. Conceptual model of the influence of caregivers’ social processes on children's environments and outcomes. The National Institute of Mental Health's (NIMH) Research Domain Criteria (RDoC) initiative provides a useful framework for extending the study of children's risk for psychopathology by assessing their caregivers’ social processes at multiple levels of analysis. The four subconstructs of affiliation and attachment, social communication, perception and understanding of the self, and perception and understanding of the child, influence the caregiver–child relationship, which is an environmental context for the child's development. In turn, the caregiver–child relationship affects the child's neurodevelopment and, ultimately, risk for psychopathology. These effects are specific to the focal child, are dynamic within the dyad, and unfold over time. Figure created with BioRender.com.

Caregiver–child Relationships and the RDoC Social Processes Domain

The social processes domain is broadly defined as systems that underlie behaviors in interpersonal interactions. Below, we first elaborate on the specific constructs that form the social processes domain and their relevance to caregiving relationships. Next, we provide recommendations for the study of these constructs in caregivers by integrating recommendations from the RDoC Matrix, the National Advisory Mental Health Council (NAHMC) Workgroup on Tasks and Measures for RDoC (NAHMC, 2016; NIMH, 2021), and research of the caregiver–child relationship. Finally, we provide illustrative examples of how these tasks and measures can be applied to study caregiving across units of analysis. In Table 1, we provide an overview of example measures for caregiver social processes at the levels of molecules, circuits, physiology, behavior, and self-report.

Table 1. Summary of example assessments for measurement of the caregiving environment and caregiver–child relationship by unit of analysis

This list is not exhaustive and additional assessments may be integrated and/or developed. Molecules, circuits, and physiology may be usefully measured at rest as well as in the context of specific tasks, including exposure to child stimuli and interaction with the child. HPA = hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal

Construct: Affiliation and attachment

The RDoC construct, affiliation and attachment, is particularly applicable to the study of caregiver–child relationships. This construct involves behavioral and neurobiological processes implicated in the development of social relationships, including information processing, social motivation, and approach-related behaviors. Affiliation refers broadly to social engagement and participation in positive interactions, whereas attachment refers more specifically to the development of selective and enduring close relationships (NIMH, 2021). Affiliation and attachment stands out among RDoC constructs in that it explicitly emphasizes the reciprocal interactions between the focal individual and others.

Given that caregivers generally serve to protect offspring, researchers have theorized that the caregiving system is goal-directed and evolutionarily driven, such that a caregiver's behaviors promote the child's attachments and, in turn, the child's attachment behaviors (e.g., proximity seeking) promote the child's survival (Bowlby, Reference Bowlby1982; Lyons-Ruth & Block, Reference Lyons-Ruth and Block1996; Solomon & George, Reference Solomon and George1996). Whereas certain caregiving behaviors (e.g., soothing the child's distress) promote the child's sense of safety and facilitate enduring attachment security (Sroufe & Fleeson, Reference Sroufe and Fleeson1986), caregiving that is neglectful or threatening may lead to attachment insecurity or disorganization (Cyr, Euser, Bakermans-Kranenburg, & Van Ijzendoorn, Reference Cyr, Euser, Bakermans-Kranenburg and Van Ijzendoorn2010). Children whose primary caregiving relationships are characterized by attachment insecurity or who are classified as having disorganized attachment are at increased risk for psychopathology (Fearon & Belsky, Reference Fearon and Belsky2011). In contrast, secure attachment relationships are postulated to have positive carry over effects for socioemotional functioning across development (Kobak, Rosenthal, & Serwik, Reference Kobak, Rosenthal and Serwik2005). While attachment relationship difficulties may indicate that a child has experienced maltreatment or trauma (Beaudoin, Hébert, & Bernier, Reference Beaudoin, Hébert and Bernier2013), secure attachment relationships in the face of (non-caregiver involved) adversity appear to buffer or protect against the development of psychopathology (Belsky & Fearon, Reference Belsky and Pasco Fearon2002).

Construct: Social communication

RDoC's social communication construct includes a broad range of behavioral and neurobiological processes underlying the ability to navigate the social world. This construct is further divided into aspects of receptive and productive communication (i.e., the abilities to understand and express information, including emotional state), as well as facial (i.e., emotional expressions) and nonfacial (e.g., gestures, prosody) communication (NIMH, 2021). Although RDoC emphasizes the dynamic and interactive nature of the social communication construct, many of the suggested measures for this construct focus on individual differences in the ability to process and effectively respond to social cues in general. In the context of caregiver–child relationships, it is important to consider how caregivers’ patterns of social communication present specifically in relation to a given child.

Just as attachment behaviors and patterns are unique to the specific dyad, patterns of communication between parents and children also differ depending on the communicative partners involved (Jenkins, Turrell, Kogushi, Lollis, & Ross, Reference Jenkins, Turrell, Kogushi, Lollis and Ross2003; LaBounty, Wellman, Olson, Lagattuta, & Liu, Reference LaBounty, Wellman, Olson, Lagattuta and Liu2008; Leech, Salo, Rowe, & Cabrera, Reference Leech, Salo, Rowe and Cabrera2013; Lovas, Reference Lovas2011; Reynolds, Vernon-Feagans, Bratsch-Hines, & Baker, Reference Reynolds, Vernon-Feagans, Bratsch-Hines and Baker2019; Rowe, Coker, & Pan, Reference Rowe, Coker and Pan2004; Tomasello, Conti-Ramsden, & Ewert, Reference Tomasello, Conti-Ramsden and Ewert1990). The language parents use becomes more diverse and complex over time based on the age of the child, the child's own language competence, and the child's developing motor skills (Huttenlocher, Waterfall, Vasilyeva, Vevea, & Hedges, Reference Huttenlocher, Waterfall, Vasilyeva, Vevea and Hedges2010; Karasik, Tamis-Lemonda, & Adolph, Reference Karasik, Tamis-Lemonda and Adolph2014; Rowe, Pan, & Ayoub, Reference Rowe, Pan and Ayoub2005; West & Iverson, Reference West and Iverson2017, Reference West and Iverson2021). Although verbal communication between caregivers and children has often been studied in relation to children's cognitive development, recent data indicate that children's language environments (King, Querdasi, Humphreys, & Gotlib, Reference King, Querdasi, Humphreys and Gotlib2021) and their language skills (Hentges, Devereux, Graham, & Madigan, Reference Hentges, Devereux, Graham and Madigan2021) are associated with the development of psychopathology. Thus, characterizing caregivers’ reception and production of verbal communication, in addition to nonverbal communication, is relevant to understanding the etiology of psychological disorders.

Construct: Perception and understanding of self

The RDoC construct, perception and understanding of self, refers to the processes involved in awareness of the self, including sensitivity to fluctuations in one's own internal states as well as perceptions of one's more stable individual traits and abilities. This construct can be further subdivided into agency, involving recognition of one's own body and awareness of the self as the cause of thoughts and behaviors, and self-knowledge, which includes awareness of one's cognitive or emotional states and traits in relation to others (NIMH, 2021).

Compared to other social processes constructs, multimethod measurement of perception and understanding of self is less well defined. Yet, measurement of the self-knowledge subconstruct in particular has relevance for the study of caregiver–child relationships. The transition to parenthood marks a dramatic shift in one's conception of the self (Feeney, Hohaus, Noller, & Alexander, Reference Feeney, Hohaus, Noller and Alexander2001). Caregivers’ perceptions of their parental identity may also change across the course of their child's development (Galinsky, Reference Galinsky1987). Because defining one's own role in the family shapes expectations of other family members, verification of one's expectations about one's role as a parent predicts not only individual-level, but also family-level, well-being (Cast, Reference Cast2004). Thus, individual differences in caregivers’ ability to adjust to their shifting parental identity and to update self-knowledge contingent on their child's characteristics both influence and are influenced by the nature of the caregiver–child relationship.

Construct: Perception and understanding of others

RDoC's perception and understanding of others construct includes behavioral and neurobiological processes involved in awareness of other people, including their mental and emotional states, as well as more stable traits and abilities. This construct is subdivided into animacy perception, or the ability to recognize agency in another person, action perception which includes the ability to understand the purpose of others’ actions, and understanding of mental states, which includes recognition and understanding of others’ beliefs and emotions. Caregivers’ general empathy, involving their compassionate concern for others and their ability to take the perspective of someone else, is related to greater encouragement of child perspective taking and their children's socioemotional functioning, including greater prosocial behavior and fewer conduct problems (Farrant, Devine, Maybery, & Fletcher, Reference Farrant, Devine, Maybery and Fletcher2012; Psychogiou, Daley, Thompson, & Sonuga-Barke, Reference Psychogiou, Daley, Thompson and Sonuga-Barke2008). Caregivers who are better able to perceive and understand their own child's mental states have children who develop better theory of mind and emotion regulation skills and who are at lower risk for internalizing and externalizing problems (Camoirano, Reference Clutton-Brock2017; McMahon & Bernier, Reference McMahon and Bernier2017). Mothers who tend to reflect on their child's mental states exhibit more responsive behavior when interacting with their child (Shai & Meins, Reference Shai and Meins2018), evidence more involvement and concern for their child (Rostad & Whitaker, Reference Rostad and Whitaker2016), and engage in fewer negative caregiving behaviors, such as hostility and intrusiveness (Kelly, Slade, & Grienenberger, Reference Kelly, Slade and Grienenberger2005).

As referenced above, the related “mind perception” literature, in which adult participants rated the mental capacities of various entities (e.g., adult, infant, beetle, robot), found that perceiving someone, or something, as having greater emotional, perceptual, and cognitive abilities is associated with a greater desire to protect and care for that person or thing (Gray et al., Reference Gray, Gray and Wegner2007; Waytz et al., Reference Waytz, Gray, Epley and Wegner2010). In concert with this research, mothers who attribute to their own infant a greater ability for having thoughts and intentions engage in more sensitive parenting behavior (Feldman & Reznick, Reference Feldman and Reznick1996; Laranjo, Bernier, & Meins, Reference Laranjo, Bernier and Meins2008). Perception of one's child's mental states and capabilities is perhaps linked to parenting because child behaviors perceived as intentional are likely to elicit more attention and self-relevance compared to behaviors viewed as unintentional (Waytz et al., Reference Waytz, Gray, Epley and Wegner2010). As such, caregivers’ capacity to understand their children is likely to be an important component of research of the child's caregiving environment.

Unit of analysis: Molecules

At the molecular level, variability in caregivers’ social processes involving their children, can be studied through hormones like oxytocin and vasopressin and neurotransmitters such as dopamine and serotonin (Johnson & Young, Reference Johnson and Young2017; NIMH, 2021). Particularly relevant to the construct of affiliation/attachment in the caregiver–child relationship, oxytocin is hypothesized to facilitate bonding by interacting with dopamine in brain circuitry supporting reward processing and approach behavior (Love, Reference Love2014; Swain et al., Reference Swain, Kim, Spicer, Ho, Dayton, Elmadih and Abel2014). While dopamine enables motivation and action, oxytocin creates a state of tranquility, such that dopamine–oxytocin cross-talk enables attachments to form (Feldman, Reference Feldman2017).

Correlational studies of peripheral oxytocin in humans indicate that caregivers’ oxytocin levels are positively associated with their affiliative behaviors toward their infants (e.g., affectionate touch, delight; Apter-Levi, Zagoory-Sharon, & Feldman, Reference Apter-Levi, Zagoory-Sharon and Feldman2014; Bick, Dozier, & Bernard, Reference Bick, Dozier and Bernard2014; Feldman, Gordon, Schneiderman, Weisman, & Zagoory-Sharon, Reference Feldman, Gordon, Schneiderman, Weisman and Zagoory-Sharon2010; Feldman, Weller, Zagoory-Sharon, & Levine, Reference Feldman, Weller, Zagoory-Sharon and Levine2007; see McCullough, Churchland, & Mendez, Reference McCullough, Churchland and Mendez2013 for a review of methodological challenges in measuring peripheral oxytocin). Further, experimental evidence suggests that compared to parents who receive a placebo, parents administered intranasal oxytocin engage in more touch and positive vocalizations with their infants (Weisman, Zagoory-Sharon, & Feldman, Reference Weisman, Zagoory-Sharon and Feldman2012), activate different brain regions when exposed to infant crying (Riem et al., Reference Riem, Bakermans-Kranenburg, Pieper, Tops, Boksem, Vermeiren and Rombouts2011), and show greater neural activation to images of their own children (Li, Chen, Mascaro, Haroon, & Rilling, Reference Li, Chen, Mascaro, Haroon and Rilling2017).

Unit of analysis: Circuits

At the circuit level, subcortical connections among the hypothalamus, which produces oxytocin, the amygdala, and the striatum, including the nucleus accumbens, appear to facilitate attachment/affiliation across mammals. Further, connections of these regions with cortical regions, including areas involved in reward and emotion processing (medial prefontal cortex [PFC], orbitofrontal cortex [OFC], anterior cingulate cortex [ACC]) and areas involved in mentalizing (ventromedial PFC; superior temporal sulcus [STS], temporoparietal junction [TPJ]), are theorized to facilitate attachment/affiliation in humans, including the specific, enduring, and representation-based attachment bonds between human caregivers and their children (Feldman, Reference Feldman2015, Reference Feldman2016, Reference Feldman2017). This network of regions has been referred to as “the parental brain” (Swain, Reference Swain2011; Young et al., Reference Young, Parsons, Stein, Vuust, Craske and Kringelbach2017).

Currently recommended RDoC paradigms for assessing brain circuitry related to social processes do not explicitly assess the parental brain network (NAHMC, 2016). Yet, researchers have attempted to elicit activation of circuits involved in caregiver–child relationships using task-based functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). For example, several studies have found that mothers activate areas in affiliation-related circuitry when viewing images of their own versus other children (Atzil, Hendler, & Feldman, Reference Atzil, Hendler and Feldman2011; Leibenluft, Gobbini, Harrison, & Haxby, Reference Leibenluft, Gobbini, Harrison and Haxby2004; Strathearn, Li, Fonagy, & Montague, Reference Strathearn, Li, Fonagy and Montague2008, Reference Strathearn, Fonagy, Amico and Montague2009). Abraham et al. (Reference Abraham, Hendler, Shapira-Lichter, Kanat-Maymon, Zagoory-Sharon and Feldman2014) found that both mothers and fathers showed greater activation in several regions implicated in emotion processing and mentalizing in response to watching themselves interact with their infants compared to control stimuli. Not surprisingly, the extent to which an individual is involved in caring for an infant – a potential correlate of the degree of affiliation with the infant – matters for how the parental brain network functions. For example, among first-time mothers, more time as a parent (i.e., later postpartum months) is associated with greater left amygdala functional connectivity to the ACC and nucleus accumbens and greater cortical thickness in the PFC (Dufford, Erhart, & Kim, Reference Dufford, Erhart and Kim2019; Kim, Dufford, & Tribble, Reference Kim, Dufford and Tribble2018). Compared to secondary caregiving fathers, primary caregiving fathers exhibit greater amygdala activation when viewing recordings of their interactions with their own infants compared to viewing recordings of unfamiliar dyads (Abraham et al., Reference Abraham, Hendler, Shapira-Lichter, Kanat-Maymon, Zagoory-Sharon and Feldman2014)

Although we currently lack validated stimuli of infant faces, validated facial stimuli of children (Egger et al., Reference Egger, Pine, Nelson, Leibenluft, Ernst, Towbin and Angold2011) and preschoolers (LoBue & Thrasher, Reference LoBue and Thrasher2014) can be used to measure variation in brain function related to caregivers’ reception of facial communication in general. In addition to the primary visual cortex, receptive processing of emotional faces activates regions including the fusiform face area, inferior frontal gyrus (IFG), ACC, and amygdala (Sabatinelli et al., Reference Sabatinelli, Fortune, Li, Siddiqui, Krafft, Oliver and Jeffries2011), with reception of vocal communication involving the superior temporal sulcus, superior temporal gyrus (STG), and IFG (Belin, Bestelmeyer, Latinus, & Watson, Reference Belin, Bestelmeyer, Latinus and Watson2011; Skeide & Friederici, Reference Skeide and Friederici2016). Relevant to reception of nonfacial communication, researchers have also used acoustic stimuli to examine brain circuits involved in perception of infant cries. Contrasted with other emotional sounds, infant cries both specific to one's own infant and infants in general elicit greater activation in mothers’ IFG, STG, and the supplementary motor area, which is involved in preparing to move or speak (Bornstein et al., Reference Bornstein, Putnick, Rigo, Esposito, Swain and Suwalsky2017). Notably, nonmothers do not show this pattern of activation, suggesting that changes in responsivity to infant communication across the transition to parenthood are normative, and highlighting the possibility that caregivers who fail to show such changes are atypical. Whereas differences in brain activation to stimuli of one's own child versus another child provide evidence that a specific attachment exists, individual differences in the degree or localization of activation may yield information relevant to how the caregiver receives facial and vocal communication in the context of that caregiver–child relationship. Such individual differences have been linked to the sensitivity of mothers’ behavior toward their infant (i.e., the accuracy of their understanding and appropriateness of their responses to infant's cues; Musser, Kaiser-Laurent, & Ablow, Reference Musser, Kaiser-Laurent and Ablow2012).

The Self-Referent Encoding Task (SRET; Dobson & Shaw, Reference Dobson and Shaw1987) is the only task that is currently recommended for assessing the perception and understanding of the self. This task, subsequently adapted for fMRI, was initially developed as a behavioral measure of self-schemas assessed by encoding of positive and negative adjectives that the participant determines to be self-referent (NAHMC, 2016). At the circuit level, understanding of the self, including how individuals process self-relevant and evaluative stimuli, is associated with activation of the medial PFC and ACC (van der Meer, Costafreda, Aleman, & David, Reference van der Meer, Costafreda, Aleman and David2010; van Veluw & Chance, Reference van Veluw and Chance2014). Although no studies to our knowledge have examined brain circuitry specifically underlying perception and understanding of the self in the context of the caregiver–child relationships, tasks such as the SRET could be applied to parents.

Activation of brain regions involved in social cognition, including the medial PFC and temporoparietal areas (Schurz et al., Reference Schurz, Radua, Tholen, Maliske, Margulies, Mars and Kanske2020), is relevant to the construct of perception and understanding of others. Connections among structures in the ACC, IFG, and anterior insula are theorized to enable the caregiver to identify with their child's emotional state and to support understanding of the child's actions through mirror mechanisms, whereas fronto-parietal circuits involved in mentalizing allow the caregiver to understand the child's nonverbal communications (i.e., STS/STG, TPJ, posterior cingulate cortex [PCC], precuneus, vmPFC; Feldman, Reference Feldman2015). Functional connectivity within these networks has been tied to Caregiver×Child interactions. For example, parents who show greater connectivity among the ACC, IFG, and anterior insula when viewing recordings of their interactions with their infant engage in more parent–infant synchrony (i.e., coordination of their behaviors with their infant's signals; Abraham, Hendler, Zagoory-Sharon, & Feldman, Reference Abraham, Hendler, Zagoory-Sharon and Feldman2016). Suggesting that early life experiences influence brain circuitry important for resonating with children's emotional states, parental sensitivity is positively associated with volume of the anterior insula in mothers with no history maltreatment but is not associated with volume in this region among mothers with a history of maltreatment (Mielke et al., Reference Mielke, Neukel, Bertsch, Reck, Möhler and Herpertz2016).

Unit of analysis: Physiology

Paradigms using images and recordings of infant stimuli can also be applied to examine caregivers’ social processes at the neurophysiological level using methods like event-related potentials (ERP) and electroencephalogram (EEG). For example, ERP components including the N170, P300, and late positive potential (LPP) have been elicited among caregivers in response to infant or child emotional faces, including to images of caregivers’ own infants (Doi & Shinohara, Reference Doi and Shinohara2012; Dudek, Colasante, Zuffianò, & Haley, Reference Dudek, Colasante, Zuffianò and Haley2020; Rutherford, Graber, & Mayes, Reference Rutherford, Graber and Mayes2016). Such ERP responses may capture physiological processes involved in affiliation/attachment. An advantage of ERP and EEG methods over fMRI is higher temporal resolution. Researchers have used EEG to quantify the average latency of caregivers’ responses to infant cues, which could be leveraged to examine individual differences in these responses (Young et al., Reference Young, Parsons, Stein, Vuust, Craske and Kringelbach2017). For example, caregivers who are especially fast or delayed in their responses may show other atypical patterns of functioning in their relationship with their infant.

A range of physiological measures can be applied to assess social communication, particularly receptive communication; however, current research in this vein tends to focus on processing of specific words or parts of speech, or on characterizing pathology in language processing. Thus, the value of applying these methods to understanding how caregivers respond to their child's communicative bids is currently unknown. One measure of potential derived from EEG is desynchronization of the mu rhythm, an index of sensorimotor activity that is observed both when carrying out and observing an action. Individual differences in mu rhythm desynchronization have been linked with empathic tendencies (DiGirolamo, Simon, Hubley, Kopulsky, & Gutsell, Reference DiGirolamo, Simon, Hubley, Kopulsky and Gutsell2019), and processing of communicative stimuli (Salo, Ferrari, & Fox, Reference Salo, Ferrari and Fox2019). Infant mu rhythm desynchronization is influenced by caregiving behavior (Murray et al., Reference Murray, De Pascalis, Bozicevic, Hawkins, Sclafani and Ferrari2016; Salo, Debnath, Rowe, & Fox, Reference Salo, Debnath, Rowe and Fox2021); however, no research has examined individual differences in parents’ mu rhythm activity while processing their own child's communicative behavior.

Using EEG/ERP, researchers can further assess perception and understanding of the self and perception and understanding of others in the context of caregiving relationships. Variation in children's emotional expressions modulate both the N170 and LPP components, making these metrics particularly relevant for assessing individual differences in caregivers’ sensitivity to child cues (Kuzava et al., Reference Kuzava, Frost, Perrone, Kang, Lindhiem and Bernard2020). These measures may be relevant for prediction of the nature of the postnatal caregiving environment. For example, individual differences in mothers’ ERPs to infant face cues during pregnancy appear to predict their self-reported abilities to understand their infants thoughts and feelings during the postpartum period (Rutherford et al., Reference Rutherford, Crowley, Gao, Francis, Schultheis and Mayes2018). Moreover, maternal N170/LPP responses to child emotional faces can be enhanced through an attachment-based intervention (Bernard, Simons, & Dozier, Reference Bernard, Simons and Dozier2015). Although less work has examined EEG/ERP markers of caregivers’ perception and understanding of the self, ERPs including the N400 and LPP can be examined in response to self-referent words and phrases to assess self-concept (Kiang et al., Reference Kiang, Farzan, Blumberger, Kutas, McKinnon, Kansal and Daskalakis2017; Speed, Nelson, Auerbach, Klein, & Hajcak, Reference Speed, Nelson, Auerbach, Klein and Hajcak2016). These types of tasks and measures can be further extended to examine self-schema specifically in the context of the caregiving relationship.

Physiological measures of hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis regulation, as well as sympathetic and parasympathetic activity, such as heart rate and respiratory sinus arrythmia (RSA) are also relevant to assessing social processes involved in the caregiver–child relationship (NIMH, 2021). Highlighting the need to move beyond the study of neurobiological processes within a single individual and to instead examine the complex temporal interplay between social partners (Bell, Reference Bell2020), affiliation and attachment between caregivers and children involves physiological synchrony, or matching of biological states, that is theorized to develop in part through receptive and productive social communication (Davis, West, Bilms, Morelen, & Suveg, Reference Davis, West, Bilms, Morelen and Suveg2018). There is particularly robust evidence for concordance of maternal and child cortisol production across development (Hibel, Granger, Blair, & Finegood, Reference Hibel, Granger, Blair and Finegood2015; LeMoult, Chen, Foland-Ross, Burley, & Gotlib, Reference LeMoult, Chen, Foland-Ross, Burley and Gotlib2015; Pratt et al., Reference Pratt, Apter-Levi, Vakart, Kanat-Maymon, Zagoory-Sharon and Feldman2017; Saxbe et al., Reference Saxbe, Golan, Ostfeld-Etzion, Hirschler-Guttenberg, Zagoory-Sharon and Feldman2017).

Although physiological synchrony between caregivers and children may mark affiliation and attachment, we require additional research to understand healthy and unhealthy patterns in biological matching between caregivers and children. In contrast to behavioral synchrony, which reflects greater attunement and more positive Caregiver×Child interactions (Leclère et al., Reference Leclère, Viaux, Avril, Achard, Chetouani, Missonnier and Cohen2014), the meaning and consequences of physiological synchrony are less straightforward (Davis et al., Reference Davis, West, Bilms, Morelen and Suveg2018). For example, physiological synchrony with a caregiver who demonstrates adaptive physiological functioning may be beneficial; in contrast, physiological synchrony between children and less healthy caregivers may be deleterious. Whereas some studies indicate that physiological synchrony is weaker in contexts of risk (e.g., Woody, Feurer, Sosoo, Hastings, & Gibb, Reference Woody, Feurer, Sosoo, Hastings and Gibb2016), others find the opposite (e.g., Merwin, Barrios, Smith, Lemay, & Dougherty, Reference Merwin, Barrios, Smith, Lemay and Dougherty2018; Saxbe et al., Reference Saxbe, Golan, Ostfeld-Etzion, Hirschler-Guttenberg, Zagoory-Sharon and Feldman2017). Type of risk factor, developmental stage, the context in which physiology is assessed, and the coupling of different physiological indicators are important to consider in future research.

Unit of analysis: Behavior

The analysis of behavior provides rich and multidimensional information about the nature of the caregiver–child relationship. Assessments of caregiving behavior are necessarily conducted at the dyad level because the meaning of the behavior (e.g., whether it is sensitive or not) depends on whether it is attuned to the infants’ signals (King, Humphreys, & Gotlib, Reference King, Humphreys and Gotlib2019). Typically, caregivers’ behaviors toward their children are observed during short, structured or semi-structured laboratory-based or video-recorded at-home interactions. Often, these are subsequently reviewed by trained coders for specific behaviors and/or global ratings. More recently, researchers have used computer vision – a form of artificial intelligence that can interpret videos – to measure aspects of caregiver–child interactions that have affective meaning (e.g., touch, proximity, gaze/joint attention, and pose estimation) (Long, Kachergis, Agrawal, & Frank, Reference Long, Kachergis, Agrawal and Frank2020; Pusiol, Soriano, Fei-Fei, & Frank, Reference Pusiol, Soriano, Fei-Fei and Frank2014). Moving beyond observation of brief interactions, we are developing wearable devices (i.e., “TotTags”) to measure caregiver–child proximity in real-time across longer periods (Salo et al., Reference Salo, Pannuto, Hedgecock, Biri, Russo, Piersiak and Humphreys2020). Many researchers are also using wearable audio-recording devices to assess naturalistic caregiving behavior in the form of vocal communication (e.g., the Linguistic ENvironment Analysis [LENA] system; Gilkerson & Richards, Reference Gilkerson and Richards2008), which we have leveraged to examine infant risk for emerging psychopathology (King et al., Reference King, Querdasi, Humphreys and Gotlib2021).

At the behavioral level, the nature of affiliation/attachment in a given caregiver–child relationship can be measured through observing the degree to which parents show sensitivity and warmth when interacting with their children. Sensitive caregiving, also related to the perception and understanding of others, involves detecting, accurately reading, and responding to infant cues, thereby enhancing caregiver–child synchrony (DiCorcia & Tronick, Reference DiCorcia and Tronick2011). Given that attachments form through repeated exposure to coordinated interactive behavior (Feldman, Reference Feldman2012), the degree to which parents engage in sensitive caregiving likely influences and is influenced by the establishment of the parent's attachment to the infant (Belsky, Fish, & Isabella, Reference Belsky, Fish and Isabella1991; Suchman, DeCoste, Borelli, & McMahon, Reference Suchman, DeCoste, Borelli and McMahon2018). How much delight and enthusiasm caregivers show about their child (e.g., smiling and laughing with the child, praising the child, cuddling the child) may also reflect the quality of affiliation/attachment. Variation in caregiver sensitivity and warmth during caregiver–child interactions can be qualitatively rated using coding systems such as the Parent–Child Interaction Rating Scales (Sosinsky, Marakovitz, & Carter, Reference Sosinsky, Marakovitz and Carter2004) or the Emotional Availability Scales (Biringen, Reference Biringen2008); systems such as the Atypical Maternal Behavior Instrument for Assessment (Cooke, Eirich, Racine, Lyons-Ruth, & Madigan, Reference Cooke, Eirich, Racine, Lyons-Ruth and Madigan2020) can be used to capture disturbances in caregiving behavior that may reflect and cause disrupted affiliation/attachment. Finally, micro-analytic coding of how much caregivers touch their infant, what kind of touch they use, and the degree to which this touch is attuned to their infant's signals may also capture aspects of affiliation/attachment (Botero, Langley, & Venta, Reference Botero, Langley and Venta2019).

Caregivers who engage in sensitive behavior are demonstrating that they have accurately understood their child's communications and are adept at responding to them. In fact, when considering dyadic social communication at the behavioral level, it is difficult to divorce reception and production of communication. Behavioral evidence that a caregiver has accurately and appropriately received their child's signal (e.g., smiling/laughing when the child makes a joke), is also the production of a communication to the child. Compared to broader qualitative coding of sensitivity and warmth, caregiver's reception and production of facial and non-facial communication can be measured in greater detail through assessment of caregivers’ gaze patterns, facial expressions, and verbal communications in response to their child's facial expressions, movements, and vocalizations. For example, researchers have used eye-tracking in caregiver–infant interactions to examine development of patterns of maternal gaze across infancy (De Pascalis et al., Reference De Pascalis, Kkeli, Chakrabarti, Dalton, Vaillancourt, Rayson and Murray2017), a paradigm that could be used to examine atypical patterns and variation based on children's different communications. “Mirroring” and positive “marking” (e.g., highlighting an infant action with a smile) when interacting with infants increases with infant age and is associated with the development of infants’ own expressive communication skills (Murray et al., Reference Murray, De Pascalis, Bozicevic, Hawkins, Sclafani and Ferrari2016). Supporting the mission of RDoC, once these normative trajectories are identified, researchers may examine how deviations from typical development of caregivers' reception and production of communication may affect child risk for psychopathology.

The construct of caregiver “mind-mindedness” (Meins, Reference Meins1997) provides a useful basis for assessing caregivers’ perception and understanding of their child. Mind-mindedness, or the caregiver's tendency to attribute mental states to their child, lies at the intersection of caregivers’ representations of their child and their behavior toward their child (McMahon & Bernier, Reference McMahon and Bernier2017). Specifically, this construct captures the caregiver's understanding of their infant's emotions, preferences, and goals as well as their ability to attribute their infant's behaviors to their infant's mind (McMahon & Bernier, Reference McMahon and Bernier2017). Caregiver mind-mindedness, which may be measured by coding caregiver's spontaneous comments about their infant's mental states, is associated with mirroring of the infant's behavior during the Still-Face Paradigm, a parent–child interaction stressor (Bigelow, Power, Bulmer, & Gerrior, Reference Bigelow, Power, Bulmer and Gerrior2015). In a meta-analysis of pooled measures of caregiver mind-mindedness, reflective functioning (i.e., the ability to hold the child's mental states in mind), and insightfulness (i.e., the capacity to consider the motives underlying the child's behavior), “parental mentalization” is positively associated with caregiving sensitivity (Zeegers, Colonnesi, Stams, & Meins, Reference Zeegers, Colonnesi, Stams and Meins2017). It is possible that the ability to perceive and understand one's child as more than “an entity with needs that must be satisfied” (Meins et al., Reference Meins, Fernyhough, Wainwright, Clark-carter, Fradley and Tuckey2003, p. 1194) is requisite for the capacity to engage in effective communication with the child. An example of a current behavioral task already included in this subconstruct within the RDoC matrix is the Reading the Mind in the Eyes task (Vellante et al., Reference Vellante, Baron-Cohen, Melis, Marrone, Petretto, Masala and Preti2013) which involves matching mental states to expressions in the eyes. While this assesses general capacities, it can be modified to focus on infant and young children stimuli (see Reading the Mind in Infant Eyes; Humphreys & Piersiak, Reference Humphreys and Piersiak2019), or to focus exclusively on the target child.

Unit of analysis: Self-report

While Cuthbert and Kozak (Reference Cuthbert and Kozak2013) noted that research based only on self-report data falls outside of the RDoC approach, there is increasing openness to self-report measures in the RDoC framework, particularly as a level of analysis to complement other types of measures. Self-report measures may be particularly relevant for the assessment of social processes, given that questionnaires and interviews remain the most accessible way to capture individuals’ experiences of emotions (Barrett, Mesquita, Ochsner, & Gross, Reference Barrett, Mesquita, Ochsner and Gross2007), which commonly unfold through interaction with and representations of close others (Zaki & Williams, Reference Zaki and Williams2013).

Although RDoC self-report measures of attachment/affiliation generally focus on past attachment-related experiences within the focal individual (e.g., the Adult Attachment Interview; George, Kaplan, & Main, Reference George, Kaplan and Main1996), using the RDoC framework to examine attachment/affiliation within the caregiver–child relationship requires a focus on the caregiver's current experiences with respect to their child. A number of validated questionnaires and interviews not currently listed in the RDoC matrix are available for assessing the caregiver's emotional tie to their child (i.e., bonding) by asking about their positive and negative feelings toward their child, including the Postpartum Bonding Questionnaire (Brockington et al., Reference Brockington, Fraser and Wilson2006), the Maternal Postpartum Attachment Scale (Condon & Corkindale, Reference Condon and Corkindale1998), and the Mother-to-Infant Bonding Scale (Taylor et al., Reference Taylor, Atkins, Kumar, Adams and Glover2005). Based on a recent meta-analysis, caregivers who report higher antenatal and postnatal bonding to their infant have infants with higher quality of attachments and more optimal developmental outcomes (Le Bas et al., Reference Le Bas, Youssef, Macdonald, Rossen, Teague, Kothe and Hutchinson2020)

Caregivers’ internal working models of their children can be assessed using semi-structured interviews that allow researchers to identify themes in caregivers’ perceptions of their children. For example, the Working Model of the Child Interview (Benoit, Zeanah, Parker, Nicholson, & Coolbear, Reference Benoit, Zeanah, Parker, Nicholson and Coolbear1997; Zeanah et al., Reference Zeanah, Benoit, Barton and Hirshberg1996) provides information relevant to both the caregiver's affiliation/attachment toward their child (e.g., the intensity of their involvement with the child, their acceptance of the child, the valence of their perception of the child), and to the caregiver's perception and understanding of the child (e.g., the richness and coherence of their representation of the child). Such detailed information about caregiver's cognitive representations of their child would be more difficult to capture through other assessment approaches.

Relevant to measuring the reception and production of communication within the caregiver–child relationship, there are many questionnaires assessing caregiver's perceptions of their behavior toward their children. These measures include the Parenting Young Children questionnaire (McEachern et al., Reference McEachern, Dishion, Weaver, Shaw, Wilson and Gardner2012), the Multidimensional Assessment of Parenting Scale (Parent & Forehand, Reference Parent and Forehand2017), the Alabama Parenting Questionnaire (Essau et al., Reference Essau, Sasagawa and Frick2006), the Emotional Availability–Self-report (Vliegen et al., Reference Vliegen, Luyten and Biringen2009), and the Maternal (Non) Responsiveness Questionnaire (Leerkes & Qu, Reference Leerkes and Qu2017). Although self-report measures of caregiver's communication toward their children are more accessible than are observational measures, it is important to consider that these measures may be subject to distortion, especially when the focus is on caregiver's negative behaviors (Morsbach & Prinz, Reference Morsbach and Prinz2006). Results of a meta-analysis indicate that the overall association between observational and self-report measures of caregiving behavior is robust but small (Hendriks, Van der Giessen, Stams, & Overbeek, Reference Hendriks, Van der Giessen, Stams and Overbeek2018).

Perception of others can be assessed through tasks involving interpretations of others’ beliefs and intentions, gaze following, and imitation. For example, the RDoC (NAHMC, 2016) recommends the Why/How Task (Spunt & Adolphs, Reference Spunt and Adolphs2014), which involves reflecting on an individual's actions in terms of their behaviors (how) and intention (why), and has been adapted to focus on parent's mentalizing in response to young children's actions (Cardenas et al., Reference Cardenas, Kujawa, Letterie and Humphreys2020). Perspective taking and empathy towards others generally are often assessed through the Interpersonal Reactivity Index (IRI; Davis, Reference Davis1983), but the IRI can be adapted to be about one's child (Stern, Reference Stern2016) allows for this more specific assessment. In fact, Salo, Schunck, and Humphreys (Reference Salo, Schunck and Humphreys2020) obtained both versions of the IRI (dispositional and modified toward one's child) in parents of young children, finding that although these measures of empathy were correlated, higher levels of empathy were found for one's child relative to general others. Further, parental depressive symptoms were associated with lower child-specific empathy even after accounting for their empathy towards others generally.

Caregivers’ perception and understanding of self in general can be assessed using self-report measures such as the Levels of Emotional Awareness scale (Lane et al., Reference Lane, Quinlan, Schwartz, Walker and Zeitlin1990) and Attributional Styles Questionnaire (Peterson et al., Reference Peterson, Semmel, von Baeyer, Abramson, Metalsky and Seligman1982). Within the context of the caregiver–child relationship, there are also self-report measures that focus on perceptions and understanding of one's identity and capability as a parent. For example, the construct of parenting self-efficacy involves the caregiver's belief in the ability to successfully perform as a parent, and can be assessed using questionnaires such as the Karitane Parenting Confidence Scale (Črnčec et al., Reference Črnčec, Barnett and Matthey2008). The Parental Reflective Functioning Questionnaire assesses the caregiver's ability to reflect both on their own and their child's mental states (Luyten et al., Reference Luyten, Mayes, Nijssens and Fonagy2017). While generally better outcomes are found in children who have parents who report higher levels of parental self-efficacy (Jones & Prinz, Reference Jones and Prinz2005) and self-reflection (Camoirano, Reference Camoirano2017), exploring these constructs in models that account for alternative explanations, including intervention studies, is important for determining causal associations.

Recommendations and Future Directions for Advancing Risk and Resilience Research in Developmental Psychopathology

Applying an RDoC lens allows for new opportunities in studying the caregiver–child relationship and interventions aimed at improving the early caregiving environment. The caregiver–child relationship has been the topic of hundreds of thousands of theoretical and empirical manuscripts, yet various schools of thought (e.g., behaviorism, psychoanalysis) have tended to work independently to examine this relationship. The RDoC social processes domain offers an opportunity to bridge these different theoretical camps and research traditions by providing a common language for and multilevel perspective on assessing caregiving relationships. We agree with the points argued by Garber and Bradshaw (Reference Garber and Bradshaw2020) regarding the potential utility in using the current terminology in RDoC in settings outside of research (e.g., with community practitioners). Using a common language to describe features of the parent–child relationship may remove the tendency to focus only on features that align with one's theoretical tradition (e.g., attachment theory vs. behavioral), to assume that the same term means the same thing for everyone, and to believe that different terms necessarily apply to different features.

The dimensional nature of individual differences in the caregiver–child relationship

The RDoC framework is appropriate for investigating the caregiver–child relationship because it facilitates study of individual differences conceptualized as falling along continua rather than dichotomously present or not. We have previously made the case for considering the caregiving environment not only within the range of adversity or within the range of more typical experiences, but across the full span of severe psychosocial deprivation to enrichment in order to accurately model the relations among features of the caregiver–child relationship, risk factors, and children's developmental outcomes (King et al., Reference King, Humphreys and Gotlib2019). Importantly, a dimensional approach to assessing constructs in the caregiver–child relationship provides the opportunity to identify nonlinear associations between aspects of the caregiving relationship and child outcomes. With respect to clinical practice and the dissemination of research to the public, identifying where an individual falls on a continuum of functioning – as opposed to whether or not they exhibit behavior in a manner that falls above or below an arbitrary cut-point – may result in less stigmatization for caregivers, particularly for those who are experiencing difficulties. Characterizing behaviors along dimensions results in more neutral and descriptive language (e.g., “difficulty in the perception of others” vs. “poor parenting”), which may come across to caregivers as less pejorative as well as offer a more concrete view of where improvements may be focused

Development of the caregiver–child relationship

As previously mentioned, the characteristics of one caregiver–child relationship are not traits. Instead, these characteristics can change across time as both parents and children develop (Kochanska et al., Reference Kochanska, Boldt and Goffin2019). Thus, it is important to consider how the caregiver–child relationship changes in concert with the dyad's development. For example, the impact of the nature of parents’ attributions about the capacities of their child may depend on the child's developmental stage. On the one hand, assigning high levels of agency to a young child who is having a tantrum (i.e., “my child is highly capable of controlling their emotions”) may lead to assuming that the child is intentional in their outburst, rather than in need of caregiver co-regulation. On the other hand, underestimating a young child's ability to perceive and learn from variation in their environment has risks (e.g., “my child does not notice when I argue with my partner” risks exposing the child to threatening contexts; “my child cannot yet benefit from talking about emotions” risks failing to provide appropriate emotional socialization). In fact, inappropriate beliefs in the agency and capabilities of children may increase risk for maltreatment (Bugental & Johnston, Reference Bugental and Johnston2002). By comparison, a more accurate understanding of infants’ capabilities may lead to supportive interactions and appropriate scaffolding across domains of development. Parenting behaviors must be sensitive to the changing needs of the child.

Parents also develop, entering new phases of life and taking on new identities (e.g., if they have another child; if they separate from a partner). Although longitudinal studies with larger sample sizes are needed to better understand how parents’ life stages are associated with trajectories of caregiving, new stages in parents’ lives are likely to influence their social processes in ways that affect their relationship with the focal child. For example, with the birth of a second child, some caregivers become harsher and less positive with their first born child (Kojima, Irisawa, & Wakita, Reference Kojima, Irisawa and Wakita2005), and the first born child may evidence lower attachment security (Teti, Sakin, Kucera, & Corns, Reference Teti, Sakin, Kucera and Corns1996). Overall, by dimensionally characterizing the caregiver–child relationship, including through assessment of caregivers’ social processes, researchers may more readily adapt assessments to the relevant developmental stage of the dyad while maintaining consistent terminology for the constructs of interest.

Multidimensionality of the caregiver–child relationship

Applying a multidimensional framework, as in RDoC, to understand the occurrence, causes, and impact of the caregiver–child relationship brings conceptualization of the caregiving environment and a child's early experiences in line with recent theory and findings. Characterizing caregiving–child relationships and early childhood experiences across multiple dimensions has gained traction, particularly in research of early adversity (King et al., Reference King, Humphreys and Gotlib2019; McLaughlin, Sheridan, & Lambert, Reference McLaughlin, Sheridan and Lambert2014; Zeanah & Sonuga-Barke, Reference Zeanah and Sonuga-Barke2016). Current perspectives debate the merits of “lumping” versus “splitting” among different experiences characterized as adversity (see McLaughlin, Sheridan, Humphreys, Belsky, & Ellis, Reference McLaughlin, Sheridan, Humphreys, Belsky and Ellis2021; Smith & Pollak, Reference Smith and Pollak2021), including specifically whether threatening experiences differ in their impact from experiences of neglect (Machlin, Miller, Snyder, McLaughlin, & Sheridan, Reference Machlin, Miller, Snyder, McLaughlin and Sheridan2019; McLaughlin, Weissman, & Bitrán, Reference McLaughlin, Weissman and Bitrán2019) as well as differentiating the impact of environmental harshness and unpredictability (Ellis, Figueredo, Brumbach, & Schlomer, Reference Ellis, Figueredo, Brumbach and Schlomer2009). Highlighting the need to consider multiple dimensions of the caregiver–child relationship that define the child's early environment, empirical data support delineating dimensions of adversity, and further suggest that yet another dimension of the caregiving environment – sensitive caregiving behavior – can moderate the impacts of both harshness and unpredictability (Belsky, Schlomer, & Ellis, Reference Belsky, Schlomer and Ellis2012). Studying specific dimensions of the caregiver–child relationship in isolation may obscure a more complete understanding of the spectrum of childhood experiences and their impact on children's risk for psychopathology.

Identifying where parents have strengths and weaknesses, including within RDoC social processes constructs, combined with an understanding of the impact of different patterns of caregiving behaviors, could lead toward parenting interventions aligned with the principles of precision medicine. This is consistent with the suggestion by Shankman and Gorka (Reference Shankman and Gorka2015) to administer a battery of assessments that tap into the RDoC constructs to inform intervention recommendations. We share excitement about this possibility, though the goal would be to support individuals through preventive interventions as they transition to parenthood and/or individuals who are parents of infants and young children presenting with difficulties in pediatric or community mental health settings. Identifying a caregiver's unique constellation of strengths and weaknesses, particularly within the context of their relationship with a specific child, can result in a parsimonious and targeted set of interventions, customized to the parent and that relationship. Such an approach may include psychoeducation, parenting skills training, individual therapy, and connecting families with public assistance programs.

Conclusions

The caregiver–child relationship is fundamental to understanding the etiology of psychopathology, yet the ability to use RDoC to characterize this relationship has yet to be realized. To date, the RDoC framework has been used to characterize processes that occur within the focal individual in order to understand that individual's risk for psychopathology. In this paper we argue that the RDoC initiative may be useful for characterizing processes that unfold between individuals in order to understand the development of psychopathology. Specifically, we have considered caregiver social processes as they relate to the caregiver–child relationship, and have illustrated how scientists may operationalize these processes in order to characterize the early environment and investigate risk for psychopathology. Importantly, our discussion of how to apply RDoC to the study of the caregiver–child relationship has not been exhaustive. While the social processes domain may be especially amenable to study of the caregiver–child relationship, other constructs such as threat (some parents report hypervigilance to potential threats related to the child), reward (some parents report falling “in love” with their infant), and cognitive control (parents must select and maintain goals related to their child) may be relevant to characterizing the caregiver–child relationship. Beyond specific constructs related to the caregiver–child relationship, core tenets of the RDoC framework – including understanding the etiology of psychopathology through analysis of mechanisms across units, conceptualizing human functioning as continuous and multidimensional, and using shared terminology – can improve and expand how we conceptualize and study the caregiver–child relationship.

Funding Statement

This research was supported by the American Psychological Foundation (LK), the Caplan Foundation for Early Childhood (KH), the Jacobs Foundation (KH: 2017-1261-05; 2016-1251-07), the National Institute of Child Health and Development (VS: F32HD100079), the National Institute of Mental Health (AK: R21MH122781), and the Stanford Institute for Research in the Social Sciences (LK).

Conflicts of Interest

None.