More so than other psychologists, those of us who study children must recognize that they are not merely subjects but partners in our research, and we owe something to them. (Zigler, Reference Zigler1998, p. 536)

With this Special Issue dedicated to Ed Zigler, the present article has three discrete but related sections. At the core of the article are new findings from a study by the present team of researchers on adolescents’ resilience in face of the COVID-19 pandemic. The first and third sections – flanking the study during COVID – present ways in which Ed's tutelage has been at the base of three decades of programmatic research by the first author, who is referred to in first-person singular through these two parts for the sake of brevity. Salient lessons learned from Ed across specific streams of research are detailed in the introductory section; the concluding section provides a commentary integrating major themes spanning this body of work.

Background

Considering the many invaluable lessons I learned from Ed as his doctoral student (1984 to 1988), three themes have remained at the core of my own applied work over the last 30 years. First, any group of children or families known to be vulnerable deserve our full attention as developmental psychologists. We owe it to the children and families whom we study to bring back our research findings toward improving their life circumstances (Zigler, Reference Zigler1998). Second, in efforts to bring science to interventions, it is critical to closely involve the intended recipients, offering services in people's everyday communities (Zigler, Finn-Stevenson, & Linkins, Reference Zigler, Finn-Stevenson and Linkins1992; Zigler & Styfco, Reference Zigler and Styfco1995; Zigler, Taussig, & Black, Reference Zigler, Taussig and Black1992). Third, researchers must communicate central findings beyond academe to lay folk and policy makers, and do so expeditiously. Otherwise as we wait for the “ideal study” to happen, policy makers are implementing major decisions with no scientific input (Zigler, Reference Zigler1998; Zigler & Styfco, Reference Zigler, Styfco, Paris and Wellman1998).

From a conceptual perspective, I have remained deeply influenced by Ed's book co-authored with Marion Glick on developmental approaches to adult psychopathology (Zigler & Glick, Reference Zigler and Glick1986), described by Dante Cicchetti as a “monumentally important scientific and social political work” (Cicchetti, Reference Cicchetti, Zigler and Glick1986, p. xii). A core tenet through this book was that high developmental levels can bring several advantages for individuals’ psychological adjustment, but there can also be costs. On the positive side, developmentally sophisticated individuals have good coping skills and histories of successes at school or work. At the same time, they have greater perceptiveness and sensitivity to the vicissitudes of life, and thus are potentially more affected by changing life circumstances (in today's parlance, these would be the orchids as opposed to the dandelions within theories on differential susceptibility; Ellis, Boyce, Belsky, Bakermans-Kranenburg, & Van IJzendoorn, Reference Ellis, Boyce, Belsky, Bakermans-Kranenburg and Van IJzendoorn2011). Discussions that follow summarize how Ed's thinking has remained at the core of different threads in my program of research. (Note: When citations are not provided for individual studies, the reader is referred to summary articles encompassing them.)

High developmental levels: Benefits and costs

Ed's thinking about development and psychopathology was at the base of my dissertation work, which was focused on resilience among inner-city adolescents with two goals. One was to illuminate major risk and protective factors, following the groundbreaking Garmezy, Masten, and Tellegen (Reference Garmezy, Masten and Tellegen1984) paper, and the second was to determine whether highly stressed inner-city teens who seemed “resilient” – doing well at stage-salient tasks including academic performance – may experience covert distress. Findings on intelligence as a potential risk-modifier corroborated Ed's theoretical paradigm, showing that inner-city teens with high IQs generally fared better than those with lower intelligence; but when levels of life stress were high, they lost much of this advantage. Several subsequent studies with adolescents and adults replicated the general finding that those at high developmental levels tend to be more sensitive than others to increasing troubles in their lives (these are summarized in Luthar, Reference Luthar1999; Reference Luthar, Cicchetti and Cohen2006).

The second broad theme to emerge in my early work with Ed was that resilience is not a unidimensional construct (Luthar, Doernberger, & Zigler, Reference Luthar, Doernberger and Zigler1993; see also Infurna & Luthar, Reference Infurna and Luthar2017). I did find, as expected, that inner-city teens who were manifestly resilient – with good academic records and behavioral competence despite high life stress – reported relatively high depression. In addition, subsequent studies showed that notable success at one stage-salient developmental task (acceptance by peers) seemed to coexist with significant problems in other important domains (disruptive behaviors at school; for a summary of these studies, see Luthar, Reference Luthar1999; Reference Luthar, Cicchetti and Cohen2006).

Findings of peer approval for counter-conventional behaviors led to a question: Was this an inner-city phenomenon, or more broadly, an adolescent phenomenon? A comparative study of high school students from relatively low- and high-income communities suggested it was the latter (Luthar & D'Avanzo, Reference Luthar and D'Avanzo1999). Among suburban youth as well, high peer status was linked with counter-conventional behaviors; in this case, high self-reported drug and alcohol use. Another unexpected finding to emerge was that overall, the suburban youth reported poorer social-emotional adjustment as compared to their inner-city counterparts, especially with regard to frequency of drug and alcohol use.

When a group is found to be vulnerable, learn why this happens

The Luthar and D'Avanzo (Reference Luthar and D'Avanzo1999) paper led to pursuit of Ed's first major lesson in applied developmental science: When you find a group that seems to be vulnerable, follow up to understand the “whys.” Both Ed and Urie Bronfenbrenner emphasized that family socioeconomic status (SES) is simply a social address (Zigler, Lamb, & Child, Reference Zigler, Lamb and Child1982); for developmental scientists, the charge is to disentangle underlying processes. In other words, assuming that the findings are shown to be generalizable across different study samples and locations, we must set about uncovering risk and protective processes that are salient in that socioeconomic context (Luthar, Reference Luthar1999).

Two ensuing cross-sectional studies with middle school students, in a different Northeast suburb, showed that there were signs of elevated psychopathology beginning at around 7th grade (for summaries, see Luthar, Barkin, & Crossman, Reference Luthar, Barkin and Crossman2013). Later studies with different high schools added further evidence of generalizability. A 2012 article presented findings on three high school samples – from two public schools, in the Northeast and Northwest, respectively, and a Northeast private school. Students from all three institutions showed elevations compared to national norms on one or more areas of psychopathology, including serious internalizing and externalizing symptoms and substance abuse (see Luthar et al., Reference Luthar, Barkin and Crossman2013).

With regard to mechanisms or processes, cross-sectional studies in relatively affluent school communities suggested the role of several socializing dimensions known to be critical for adolescents in general, as is true for youth in low SES settings (Garcia Coll et al., Reference Garcia, Lamberty, Jenkins, McAdoo, Crnic and Wasik1996). These included lack of parental supervision and perceived harshness, and (again), peers’ approval of substance use. Other early findings also showed that overall, students’ felt closeness to parents was no greater among suburban youth as compared to their inner-city counterparts, suggesting nontrivial stressors among these mostly white-collar families as well (see Luthar et al., Reference Luthar, Barkin and Crossman2013).

Apart from such socializing processes explaining within-group variations, what still needed attention was why these adolescents as a group might be at greater risk than normative samples of teens in the United States. Early findings countered some presumptions (e.g., showing that overscheduling was not a likely cause) and, more importantly, provided initial insights into context-specific influences, as Ed urged. Specifically, two unique dimensions were identified as likely important in these high-achieving school settings (see Luthar, Kumar, & Zillmer, Reference Luthar, Kumar and Zillmer2019b; Luthar et al., Reference Luthar, Barkin and Crossman2013). The first was perceptions of parents’ values: Students who felt their parents placed more value on personal decency, relative to personal accomplishments, fared better than the others. The second was perceived parent containment of substance use; that is, the seriousness of repercussions on discovering drug or alcohol use (which as noted earlier, was found to be elevated in Northeast suburbs). Perceived containment had robust links with self-reported substance use, even after considering traditional measures of monitoring and supervision.

The importance of perceived parent containment was further highlighted in a long-term prospective study, wherein students were assessed from ages 12 to 28 years (summarized in Luthar et al., Reference Luthar, Kumar and Zillmer2019b). Findings clearly showed that although substance use was somewhat commonplace among high school peers, it is by no means inconsequential. Parent containment was inversely linked with students’ levels of use in high school, and these, in turn, were linked with elevated risk for diagnoses of addiction many years later, in early adulthood. Furthermore, rates of young adult drug or alcohol dependence were found to be at least twice as high as those in national norms. Collectively, these new findings had clear implications for prevention, cautioning against laissez-faire parental attitudes to teens’ substance use in relatively affluent communities. These issues have been highlighted in presentations for parents and more broadly, through journalistic reports, again, following Ed's exhortations to communicate research findings clearly and quickly to stakeholders outside of the academy (a list of these reports is available on request).

Accumulating findings over time led to refinements in our empirical work and dissemination of major findings to collaborating school communities. My colleagues and I developed a comprehensive battery to capture critical mental health indices as well as salient aspects of students’ close relationships (with adults and peers) that might be modified toward promoting resilience. In 2019, over 15,000 youth were assessed with this measure, called the High Achieving Schools (HAS) Survey (Authentic Connections, 2019). Results were analyzed and presented back to participating schools within weeks after they had administered the survey. Each school was able to view their students’ adjustment levels compared to others from similar schools across the country. As importantly, for each school, multivariate analyses illuminated the “top three” risk and protective processes most warranting attention in their own communities, along with associated directions for interventions. Specific initiatives, within these data-driven interventions, were delineated in on-campus discussions with major stakeholder groups including faculty, administrators, counselors, parents, and students.

Accumulating evidence on HAS youth also led to a revised theoretical model of the likely mechanisms or processes exacerbating their vulnerability. This new conceptual model indicated, first, that it is not the affluence of students’ own families that confers risk but rather, being in a high-achieving school where pressures to achieve and excel are constant (Luthar et al., Reference Luthar, Kumar and Zillmer2019b; National Academy of Science, Engineering, & Medicine [NASEM], 2019). Second, these ongoing achievement pressures are multiply determined, reflecting equifinality (Cicchetti & Rogosch, Reference Cicchetti and Rogosch1996); they stem from peers, parents, teachers, communities, global competitiveness, and college admissions criteria. Third, this phenomenon extends across public and private schools, in cities and suburbs, and across different parts of the country; the common denominator is being in the top quartile or so of standardized test scores. Fourth, whereas there are several risk and protective processes potent across schools (e.g., high ongoing competitiveness), empirical evidence illuminates several variations in those that most need attention within individual school communities.

Support parents in their communities

Another major thread of work stemming from my training with Ed was to ensure support for parents of all at-risk children. This was clear in his models for both Head Start and Schools of the 21st Century, wherein both emphasized the need to support parents of relatively low SES, and to connect them with existing resources in their own communities.

My own efforts in this regard took the form of support groups for low-income mothers with histories of addiction, via the Relational Psychotherapy Mothers Groups intervention. This was a supportive, insight-oriented program offered to women at their methadone clinics, once a week for six months. Two randomized trials showed that participation in groups led to significant improvements in the mothers' well-being – by self-reports as well as by other reports (for summaries, see Luthar, Kumar, & Benoit, Reference Luthar, Kumar and Benoit2019a; NASEM, 2019).

Several years later, this supportive group approach was modified for mothers at the opposite end of the socioeconomic spectrum, also at-risk given high caregiving burden: mothers who were healthcare providers. This three-month program, called Authentic Connections (AC) Groups was offered at their workplaces, again ensuring easy access. Two randomized trials were conducted, with providers at the Mayo Clinics in Arizona and Minnesota respectively. Findings showed improvements compared to controls on multiple indicators of well-being (including cortisol levels) with moderate effect sizes, and gains sustained well after the program was completed (for summaries, see Chesak et al., Reference Chesak, Bhagra, Cutshall, Ingram, Benoit, Medina-Inojosa and Luthar2020; Luthar et al., Reference Luthar, Kumar and Benoit2019a).

Perhaps most importantly – in light of the current pandemic – AC Groups were shown to be effective with mothers when conducted in virtual format as well (Luthar et al., Reference Luthar, Kumar and Benoit2019a). In the NASEM (2019) consensus study report on equity in childhood, AC Groups have been highlighted as a promising low-cost, effective strategy to foster resilience among at-risk mothers and thus, their children. I continue efforts to bring virtual support groups to parents and educators, with descriptions of how they might each develop such groups in their own circles through the current pandemic. As Ed often said, beneficial interventions do not require a PhD but can and should be delivered by folk with and for each other (Zigler, Reference Zigler1998).

The COVID-19 pandemic: Risk and resilience among adolescents

The second section of this article presents a study of risk and resilience among adolescents implemented during the first two months of school closures following the spread of COVID-19 in the United States. The sample consists of over 2,000 students from five HASs in the US, assessed using the Student Resilience Survey (SRS; see Methods for details). Central goals were (a) to assess rates of clinically significant depression and anxiety and (b) to illuminate potential risk and protective factors associated with well-being, using a mixed-methods approach. The goal was to discern major themes that recurred – across schools and analytic approaches – toward illuminating issues most warranting attention in preventive interventions.

COVID-19, school closures, and HAS students

School closures and the move to distance learning have considerable implications not only for students’ mastery of academic material but also for their mental health (e.g., Morrison, Reference Morrison2020). Increasingly, there have been cautions that mental illness is the second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic (Uguen-Csenge, Reference Uguen-Csenge2020). Stress levels are high given rampant fears about illness and death, economic security, and feelings of isolation, and they are exacerbated among parents with children at home (American Psychological Association, 2020).

At this time, little is known about the effects of COVID on adolescents’ depression or anxiety. On the one hand, teens have experienced a loss of daily routines and structure; this lack of routine can be detrimental for well-being. They have also been deprived of in-person interactions with friends – socially, romantically, and in extracurricular activities. On the other hand, some HAS youth may have experienced a reprieve from multiple time pressures (see Luthar et al., Reference Luthar, Kumar and Zillmer2019b). In schools where average achievement levels are high – among the top 25% of test scores in the country – it could be a relief for some students to have less intensive and more flexible daily schedules, as well as greater leeway in hours for sleep.

The first question addressed here, therefore, was whether there are any discernible trends in levels of serious mental health issues among HAS adolescents since school closures. Of central interest were symptoms of depression and anxiety, as both are especially elevated among HAS students (Luthar et al., Reference Luthar, Kumar and Zillmer2019b). The goal here was to compare rates of clinically significant symptoms currently with rates previously documented in a study of almost 3,000 high school students assessed in 2019; overall, about 8% had symptoms of depression or anxiety in the clinically significant range, on a well-validated measure called the “Well-Being Index” (WBI; Luthar, Ebbert, & Kumar, Reference Luthar, Ebbert and Kumarin press).

For comparative purposes normative rates are also available on both these symptoms among almost 10,000 students who had been assessed on the HAS Survey in 2019 (Authentic Connections, 2019), but not part of the Luthar et al. (Reference Luthar, Ebbert and Kumarin press) study. This larger 2019 cohort happened to include two of the schools in the present study. Thus, it was possible to compare these two schools’ own rates of serious distress from 2019 to 2020, and also to explore any systematic differences between them with the other three schools who were not part of prior collaborations.

The second objective of this study was to determine salient, modifiable risk and protective factors that might help schools to prioritize the major intervention needs in the face of the current pandemic. To this end, the approach was similar to that used in the HAS Survey, with two modifications. First, the total time for survey completion was reduced from about 30 minutes to 10 minutes, omitting dimensions likely to be of less importance during distance learning (e.g., externalizing problems and substance abuse, as students were at home). Second, the SRS used a mixed-methods approach, with open-ended questions introduced to help illuminate concerns unique to the new circumstances of the pandemic and distance learning.

Quantitative questions on the survey (using Likert scales) assessed three aspects of academic mastery: the availability of resources needed for distance learning, the degree of felt efficacy in learning, and the ability to focus on class materials. Another set of questions pertained to central relationships in adolescents’ lives, with acknowledgement that these are both critical for resilience (Luthar, Crossman, & Small, Reference Luthar, Crossman, Small, Lamb and Garcia Coll2015; NASEM, 2019), and have inevitably been threatened by school closures. Qualitative data were considered indispensable here given the entirely unprecedented nature of current challenges; students were asked what was most concerning for them, ways in which their school could improve things, and ways in which their school was doing things well.

Method

Participants

Data presented here are based on a sample of 2,196 high school students in Grades 9 (n = 596), 10 (n = 594), 11 (n = 588), and 12 (n = 418). Participants were from five private schools all located in the South region of the United States. (Note: The accurate term for these institutions is “independent schools” but “private schools” is used here as it this is more common in everyday parlance.) These schools were selected for this report because all assessments had occurred during the first two months of distance learning; all were in the same part of the country; and all had good participation rates (70% or higher). As noted earlier, two of these five schools had also been assessed in 2019 using the HAS survey.

Breakdown of demographics by school is shown in Table 1. In the sample as a whole, 48.0% of students were male (n = 1001) and 51.6% were female (n = 1077; less than 1% of students did not report gender). Students described themselves as primarily Caucasian/White (60.3%), with other ethnicities represented as follows: Asian/Asian American/Pacific Islander (11.7%), Latinx/Hispanic (6.7%), African American/Black (12.5%), Middle Eastern (1.3%), and Biracial/Multiracial/Other (7.3%). With regard to school characteristics, average 2019 SAT percentiles ranged from 78% to 90% across the five schools (median 83%). Annual tuition across schools ranged from $24,000 to $30,000 (median $27,000) and the percentage of students on scholarship ranged from 21% to 28% (median 25%).

Table 1. Demographics of schools included in study: Grades 9–12

Note. aTo preserve the anonymity of schools, approximate values are shown for number of students enrolled in each (i.e., actual n +/− 20).

Annual tuition across schools ranged from $24,000 – $30,000, median $27,000. Percentage of students on scholarship ranged from 21% to 28%, median 25%. Dates of school closures ranged from 03/18/2020 to 03/25/2020.

Measures: Components of the Student Resilience Survey (SRS)

Depression and anxiety

The WBI is a psychometrically validated measure (Luthar et al., Reference Luthar, Ebbert and Kumarin press) consisting of 25 items assessing adolescents’ internalizing and externalizing symptoms, and feelings of isolation at school, on five subscales. For use in the SRS, the two internalizing subscales – depression and anxiety – were included, each with five items rated on a 5-point scale reflecting frequency of experiencing the symptom in question (0 = never, 4 = very often).

Among schools assessed here, reliability coefficients for WBI Depression and Anxiety indicated acceptable levels of internal consistency (e.g., α ≥ .70; Nunnally & Bernstein, Reference Nunnally and Bernstein1994). As shown in Supplementary Table 2, coefficients for Depression across schools for males and females, respectively, ranged from .78 to .85 and .81 to .88; for Anxiety, parallel values ranged from .79 to .92 and .83 to .86.

Risk and protective factors

Single items were generally used to quantitatively capture potential risk-modifiers, for a number of reasons. The first was brevity; schools desired the briefest possible survey, anticipating that students would already have fatigue with online communications. Second, single items have commonly been used to assess critical constructs in prior studies with adolescents, including not just indices of adjustment problems – for example, depression or frequency of substance use (NIDA, 2019; Zimmerman et al., Reference Zimmerman, Ruggero, Chelminski, Young, Posternak, Friedman and Attiullah2006) – but also constructs such as quality of life and relationships (e.g., Jovanović, Reference Jovanović2016; Shaw, Dooley, Cross, Zubrick, & Waters, Reference Shaw, Dooley, Cross, Zubrick and Waters2013).

Importantly, simple correlations in this study, discussed below, implied acceptable reliability of measurement. In general, validity is constrained by reliability. As described in the Results section, each single-item measure in the SRS was significantly correlated with conceptually related others, consistently across the five schools.

Learning efficacy was assessed by two single-item questions, Learning Ability and Learning Focus, respectively, assessing (a) how well students felt they were able to learn at home and (b) their level of focus during online classes, each rated on a 5-point scale from low to high. Daily Structure for fun was assessed by asking students to indicate the degree to which their typical days had specific times set aside for activities that were fun or relaxing, rated on a 5-point scale ranging from not at all to very much.

Both positive and negative aspects of relationships with parents were assessed; that is, the degree to which their parents (a) understood and helped manage their feelings (henceforth called Parent Support), and (b) were a source of stress for them (Parent Stress). In addition, students reported their satisfaction with the frequency with which they shared personal concerns with (a) adults and (b) friends at school; responses ranged from very dissatisfied to very satisfied. These variables are referred to as Sharing with Adults and Sharing with Friends.

Finally, to assess students’ perceived responsiveness of schools to new challenges, they were asked about the degree to which teachers and administrators were (a) listening to their concerns about school and (b) doing something about these concerns. Both questions used a 5-point scale ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree and were averaged to create the construct referred to as Concerns Heard. As shown in Supplementary Table 1, alpha coefficients for Concerns Heard across schools ranged from .85 to .90 (median .97) for males, and .77 to .86 for females (median .85).

Qualitative data

Students responded to three free response questions: (a) “These days, what are you most worried about?” (b) “In thinking about your school experience, what could your teachers/faculty be doing to improve things for you?,” and (c) “What are things that your school is doing well to support your overall school experience and well-being?” To code qualitative response data, a taxonomy capturing distinct themes and non-overlapping categories was developed. This initial taxonomy was created by an external consultant with expertise in coding qualitative data; in addition, an outside reviewer with classroom teaching certification reviewed the taxonomy to ensure content validity. Other team members then used early pilot data (not from this study) to categorize responses, and when there was ambiguity of classification across categories, clear inclusion and exclusion criteria were spelled out for each.

The taxonomy includes nine mutually exclusive categories; themes subsumed within these along with sample items for each are shown in Supplementary Tables 2a–2c. The categories were the following: (a) Academic Workload – the quantity/timing of assignments and ability to complete assignments; (b) Faculty Flexibility in grading and exams; (c) Faculty Support – emotional and academic; (d) Family Well-Being – health and finances; (e) Future/College – uncertainties; (f) Peer Interactions – mentions of friends; (g) Distance Learning Efficacy – ability to learn given new constraints; (h) Structure/Schedule – for school work and leisure; and (i) Activities, including athletic and other events. Students’ responses could be coded in more than one category.

Inter-rater reliability

Two team members coded all open-ended responses for this study, and Cohen's (Reference Cohen1960) kappa coefficients were calculated to determine levels of agreement. Coefficients for the questions on Concerns, Areas for Improvement, and What's Going Well, respectively, were .77, .76, and .72. These values are in the Substantial agreement range of 0.61–0.80; values between 0.41and 0.60 are considered Moderate agreement and 0.81–0.99 is Almost perfect agreement (Viera & Garrett, Reference Viera and Garrett2005).

It should also be noted that as schools were given compiled results on their students, they were able to access every student response that had been classified within the major categories described earlier. In other words, within the broad categories, administrators could peruse all verbatim responses for the school, “hearing” directly from the students. These open-ended entries, like all quantitative scores, were entirely anonymous, and of course, students were free to respond as briefly or in detail as they chose.

Procedures

As part of their ongoing efforts to foster positive youth development and proactively address COVID-related challenges, school officials had administered the SRS virtually during regular school hours after the move to distance learning (dates for each school are shown in Table 1). As routinely done with such surveys, the school heads obtained passive consent from the parents, informing them about the nature of the survey, giving them the option to decline their children's participation, and assuring them of the confidentiality and complete anonymity of the data (including no transmission of IP addresses). Participation rates across schools, shown in Table 1, ranged from 70% to 99%, with a median value of 81%. Across schools, a total of 2,249 students completed the survey, with a rejection rate of 2.4% due to incomplete data, resulting in a final sample of 2,196 adolescents.

Following completion of data collection, each school shared their de-identified data with this research team, who shared summarized central findings for the school leadership team within 7–10 days using interactive dashboards. These dashboards allowed leaders to view salient quantitative and qualitative findings for the school overall, and also separately by subgroups defined by gender, ethnicity, grade level, which illuminated any subgroups especially vulnerable (e.g., gender-nonbinary students, or youth of color). Note that if any subgroup had fewer than 10 students, data on that subgroup were not shared. There was no charge to the schools for these data analyses and reports. As this study involved analyses of preexisting, de-identified, anonymous data, this study is in the category of “exempt” status per the Institutional Review Board committee at Columbia University's Teachers College, protocol number 20–161. Analyses for this study were conducted using SPSS software (IBM Corp., 2019) with listwise deletion methods for missing data, which was negligible (< 3%).

Results

Descriptive data

Simple correlations

Supplementary Tables 3–7 present simple correlations across all variables in the study for all schools, separately by gender. These tables showed the expected correlations among conceptually related single-item questions, lending support for the validity of assessments. For example, coefficients for links between Learning Ability and Learning Focus, were the following in Schools 1–5 in order, for males/females respectively: .32 / .41; .59 / .53; .60 / .45; .57 / .58 and .54 / .59. Parallel correlation coefficients for Parent Support with Parent Stress were −.59 / −.61; −.58 / −.58; −.55 / −.54; −.43 / −.62; −.41 / −.65. Finally, coefficients between Concerns Heard at school and Sharing with Adults were .29 / .43; .48 / .36; .33 / .23; .33 / .32; .42 / .34.

Clinical cutoffs/comparison to clinical norms

Figure 1 presents the percentage of students falling above clinical cutoffs on WBI symptoms (Luthar et al., Reference Luthar, Ebbert and Kumarin press); that is, those “above average” (AA) versus norms at +1.5 SDs, and “much above average” (MAA) at +2 SDs. Norms, or cutoff scores, considered in Figure 1 were based on a total of 9,025 students from 14 schools, including 11 private schools, 2 public schools and one boarding school; Authentic Connections, 2019). All of these schools had been assessed in 2019, and all had mean SAT scores above the 75th percentile as did the five schools in the present study.

Figure 1. Percentages of youth reporting clinically significant symptoms ‘Above Average’ and ‘Much Above Average’: Rates in 2019 (Schools 1 and 2) and in 2020 (Schools 1–5). Note. Black bar represents 2019 normative values for each symptom by gender.

Figure 1 presents these comparisons, separately for males and females, with AA rates on the top and MAA rates below. For each subgroup of values – for example, males’ AA Depression – the five columns on the right represent rates for the five schools assessed in 2020. To the left of these are two columns showing rates for two of the five schools that had also been assessed in 2019 on WBI Depression and Anxiety; Schools 1 and 3.

Considering, first, all 2020 data, results showed that in the vast majority of instances, rates of clinically significant symptoms were lower than those documented in 2019 norms. Of the 40 columns representing 2020 rates, it was in only five instances that values were notably greater than those from 2019, a proportion much lower than what would have been expected by chance alone (i.e., 8% vs. 50%).

The two columns on the far left of graphs in Figure 1 show that for both Schools 1 and 3, rates of clinically significant symptoms were lower in 2020 than they had been in 2019. In addition, their overall AA and MAA rates in 2020 appeared lower than those in the other three schools.

Variations in mean scores on predictor and outcome variables

Table 2 presents means and standard deviations on all variables, separately by school and for males and females. Differences in mean levels of all variables were examined using a 2 × 5 multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) according to (a) Sex (Male/Female) and (b) School (Schools 1–5). Results showed significant differences by Sex, F(10, 2055) = 35.42, p < .001; Wilks Λ = 0.85, η2 = 0.15; and by School, F(40, 7794) = 4.12, p < .001; Wilks Λ = 0.92, η2 = 0.02. The interaction between Sex and School was not significant.

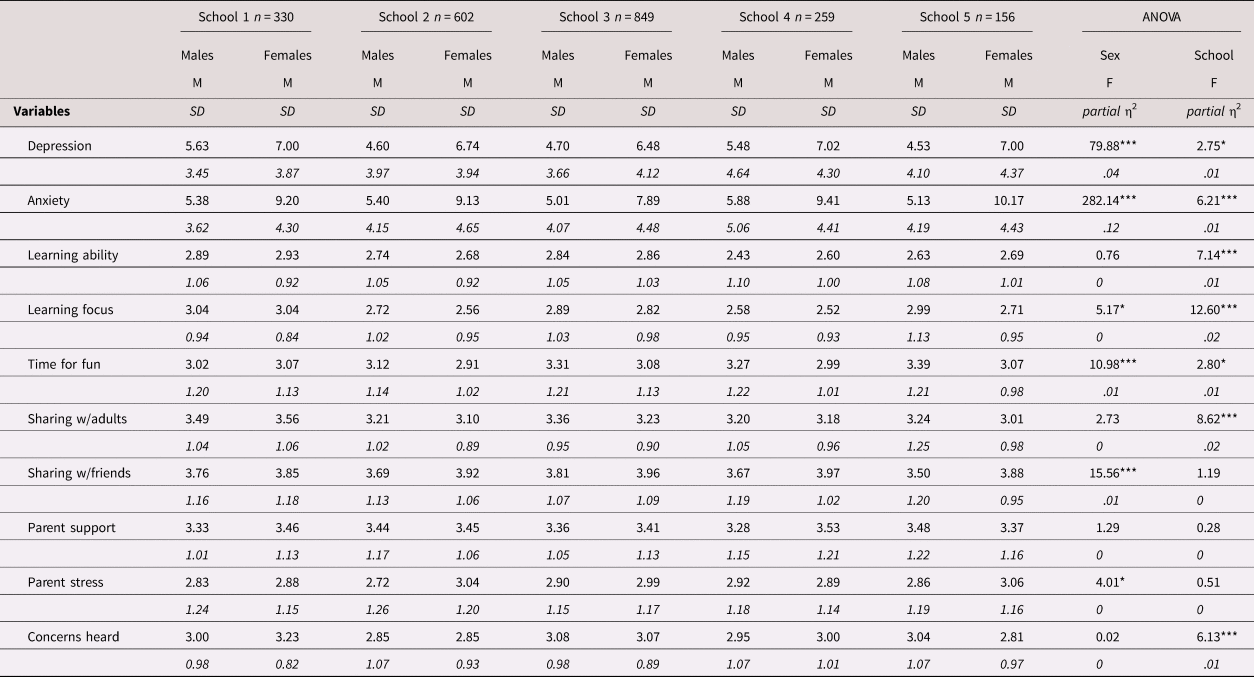

Table 2. Descriptive statistics: means and standard deviations of all variables by school and gender

Note. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

ANOVA = analysis of variance

Follow up univariate analyses of variance (ANOVAs) were conducted to identify significant mean group differences. With regard to main effects for Sex, females reported higher levels of Depression, F(1, 2068) = 79.88, p < .001, η2 = .04, and Anxiety, F(1, 2068) = 282.14, p < .001, η2 = .12. On predictor variables, differences were significant for Learning Focus, F(1, 2065) = 5.17, p < .05, η2 = .002, Time for fun, F(1, 2065) = 10.98, p < .001, η2 = .01, Sharing with Friends, F(1, 2064) = 15.56, p < .001, η2 = .01, and Parent Stress, F(1, 2065) = 4.01, p < .05, η2 = .002. Compared to females, males reported greater Learning Focus and more structured Time for Fun, and lower levels of Parent Stress, but were lower than females on satisfaction with Sharing with Friends.

Regarding main effects for School, comparisons on outcome variables were significant for Depression, F(4, 2068) = 2.75, p < .05, η2 = .01, and Anxiety, F(4, 2068) = 6.21, p < .001, η2 = .01. With regard to predictor variables, differences were significant for Learning Ability, F(4, 2065) = 7.14, p < .001, η2 = .01, Learning Focus, F(4, 2065) = 12.60, p < .001, η2 = .02, Time for Fun, F(4, 2065) = 2.80, p < .05, η2 = .01, Sharing with Adults, F(4, 2065) = 8.62, p < .001, η2 = .02, and Concerns Heard, F(4, 2064) = 6.13, p < .001, η2 = .01.

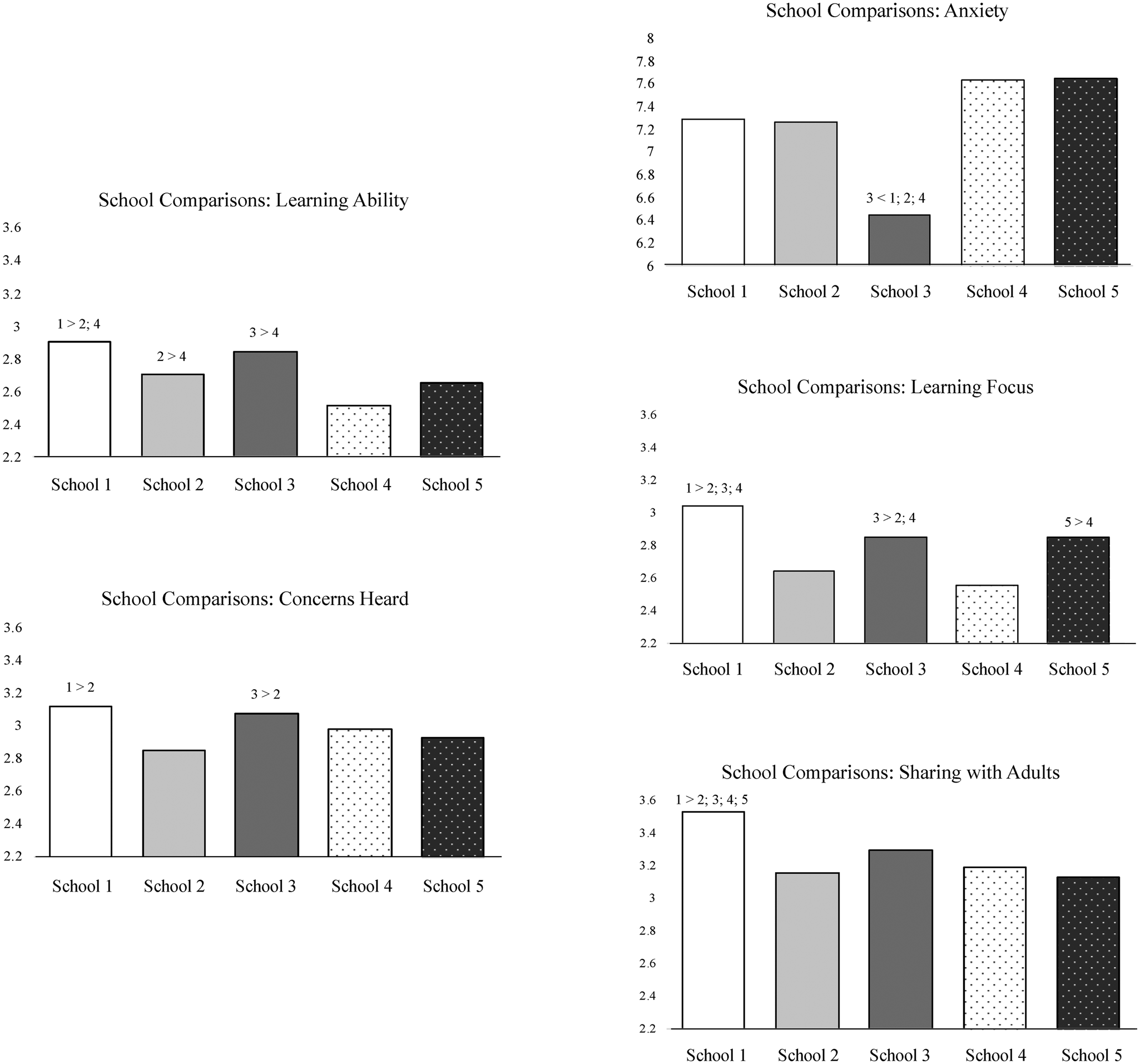

For significant School effects, post hoc comparisons were conducted using Tukey's HSD tests; these correct for family-wise error and are conservative when sample sizes are unequal (Montgomery, Reference Montgomery2013). Results are shown in Figure 2. Collectively, the findings showed that Schools 1 and 3 both fared significantly better compared to other schools on multiple variables assessed.

Figure 2. Post hoc comparisons of significant main effect differences across school in analyses of variance.

Regression analyses

Results of regression analyses are shown in Table 3, separately for the five schools. In these regressions, gender was controlled for at the outset (preliminary analyses showed similar findings for males and females). Findings showed that with Depression and Anxiety as the outcomes, respectively, overall variance accounted for (R2) ranged from .23 to .33 (median .30) and between .20 and .36 (median .28).

Table 3. Results of multiple regressions for depression and anxiety as outcomes

Note. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

a Gender: Males coded as 1 and females coded as 2; bβ = standardized beta coefficient.

With regard to unique associations for the predictor variables, results showed significant links between Parent Stress and outcomes in all ten regression analyses conducted, with beta coefficients ranging from .19 to .25 for Depression (median .22) and .16 to .25 for Anxiety (median .20). In addition, Parent Support was inversely related to Depression in all six schools, with beta coefficients ranging from −.13 to −.21, median .19. Links for other variables were less consistent, significant in 60% of analyses conducted. With Depression as the outcome, in three of five schools each, significant links were found for three other predictor variables. These included Learning Focus, with βs of −.12, −.08, and −.28 for Schools 2, 3, and 5, respectively; Time for fun, β's of −.13, −.10, and −.10 in Schools 1, 2, and 3; and Sharing with Friends, β's −.17, −.09, and −.12 in Schools 2, 3, and 4, respectively.

Qualitative data: Coding student accounts of concerns and improvements

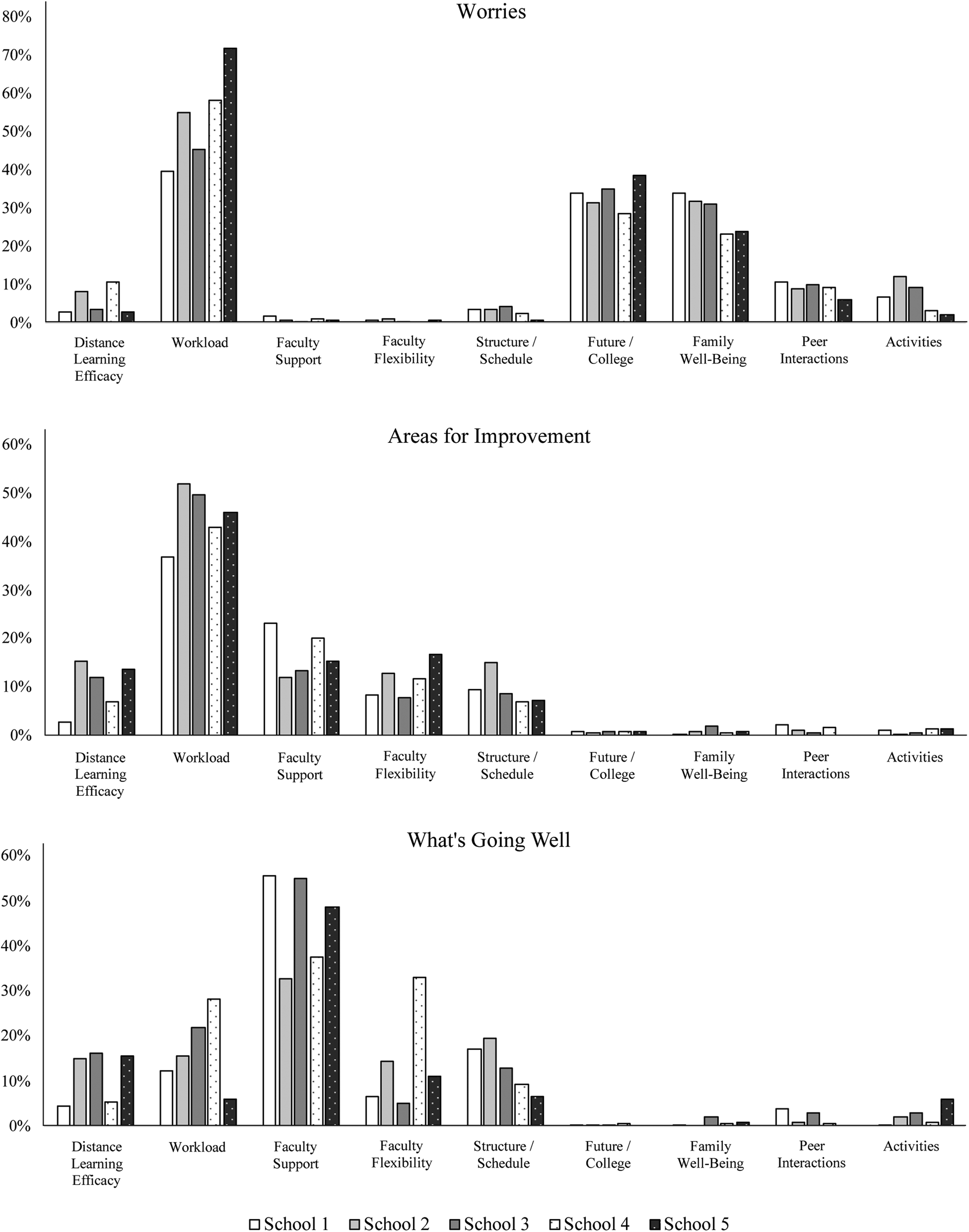

Figure 3 shows summarized results of responses to the three open-ended questions (again, sample items for all categories are shown in Supplementary Table 2). As shown in Figure 3, for Concerns, the five categories most often mentioned across schools were Workload, Future/College, and Family Well-Being, followed by Peer Interactions and Activities. Under Areas for Improvement, Workload was again the most frequently mentioned, as it was among the top five for What's Going Well. The opposite pattern was seen with Faculty Support; this was the most commonly mentioned category under What's Going Well. Other categories mentioned relatively often across both questions were Distance Learning Efficacy, Faculty Flexibility, and Structure/Schedule. Finally, under Concerns in particular, the two categories most often mentioned (following Workload) were Future/College and Family Well-Being.

Figure 3. Percentages of students mentioning discrete themes in open-ended responses.

Discussion

Considering data from five schools, rates of students with clinically significant levels of depression and anxiety were not uniformly higher, during the first few weeks of distance learning, than those documented previously in 2019; in fact, in most instances these rates were lower. Second, when multiple aspects of learning and relationships were examined as predictors in regression analyses, perceptions of parents’ functioning consistently showed strong, unique links with adolescents’ depression and anxiety. In responses to open-ended questions, workload was commonly mentioned as well as faculty support; other categories often mentioned included concerns about families’ well-being and uncertainties about the future.

Rates of clinically significant depression and anxiety: Lower than rates in 2019

Across the five schools in this study and considering both males and females, results showed limited evidence that rates of serious internalizing symptoms had increased in the early weeks of school closures. In point of fact, in four of the five schools, proportions of students reporting clinically significant internalizing symptoms – both “above average” and “much above average” (+1.5 and +2 SDs respectively) were below rates that had been computed among almost 10,000 students during 2019 across multiple administrations of the HAS Survey (Authentic Connections, 2019).

The apparently lower rates of internalizing symptoms could partially rest on some reductions in everyday stress, as noted in the introduction to this study; at the same time, it must be cautioned that HAS students (and others) will likely show increases in distress as there are continued uncertainties around the pandemic (e.g., New York Times, 2020). Regarding re-opening, for example, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP, 2020) has recommended that in the fall, students should be physically present in school as much as possible, because extended periods of time away will increase risk for social isolation and serious depression, anxiety, substance use, and suicidal ideation. Conversely, educational experts recommend that schools should focus centrally on improving distance instruction; efforts to create new, hybrid models carry risks of overwhelming teachers and could result in lower quality instruction (Pallas, Reference Pallas2020). In short, there is likely to be continued uncertainty about resuming in-person school interactions as they used to be, and these uncertainties will inevitably increase symptom levels.

Students’ distress levels are also likely to increase given rising stress among adults on whom they depend for care. Regression results reported here support NASEM's (2019) conclusions that youth mental health rests strongly on their parents’ functioning. Considering multiple predictors related to home, school, and peers, adolescents’ feelings of stress around their parents was significantly linked with both depression and anxiety in all ten of the regression analyses, as feeling supported by parents when troubled was related to lower depression in all five schools. (Three other variables that showed unique, inverse links, but not consistently across schools, were structured time for fun, sharing of concerns with friends, and ability to focus on schoolwork.)

Also relevant here are national data trends on adults’ mental health since the start of the pandemic. Between January and June of 2019, 11% of adults reported anxiety or depression (Center for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020). By early May 2020, this rate had climbed to 35.9% and by June end, was at 36.1%. Similarly, drug overdose deaths reportedly climbed by 11.4% across the first four months of 2020, likely due to increased social isolation, depression, and anxiety (Ehley, Reference Ehley2020). Considering parents specifically, the APA (2020) report showed that high COVID-related stress was reported by 46% of adults with children under 18 at home, as opposed to 28% of adults without children.

Besides parents, school adults are also going to be stretched in being able to offer psychological ‘safety nets’ for youth who struggle with distress. In this study, students’ open-ended responses indicated that in thinking of what schools were doing well, they often described outreach and support from teachers, advisors, and counselors. Juxtaposed with these data are others showing the increasing strain on these adults. Our own data on over 4,000 HAS adults (administrators, teachers, counselors, and support staff) across the country have shown that high work-related burnout was reported by 10% of respondents in March 2020, and by July, this number had climbed to over 40% (Luthar & Kumar, Reference Luthar and Kumar2020).

Using data to guide community-based interventions and policy

From the perspectives of prevention, practice, and policies, several factors indicated that the SRS assessments had been beneficial for the school communities. First, there was some comfort for school leaders in simply having rigorous data on students’ mental health and top concerns (much as they sought physical health data on COVID infections). Second, administrators appreciated the one hour face-to-face feedback sessions as they were led through details of methods used for assessments and statistical analyses, and associated recommendations with specific, actionable steps for their own school. Their ability to pinpoint subgroups consistently shown to be vulnerable in their institution was also valued. To illustrate, findings at one high school showed that juniors had higher rates of serious symptoms relative to other grades in the same school, and also relative to 11th graders, nationally; In addition they showed marked deviations on multiple risk-modifiers examined.

Third, use of these assessments reportedly helped bolster cohesiveness, helping students and staff to feel ‘tethered to their community’ through all the uncertainty and isolation wrought by COVID. Respondents explicitly appreciated these surveys as signs that the school cared about their personal well-being. Administrators’ sharing of central survey results was also helpful, both to demonstrate what was going well at their school (e.g., quoting verbatim responses), and to describe initiatives addressing suggestions noted in students’ suggestions for improvements.

Most especially, school leaders valued the concrete suggestions for steps they could take to address specific issues that were shown to be most important in their own data. Recommendations commonly included various ways to bolster ongoing community connections, including strategies from other schools that had successfully implemented them. Examples include scheduled virtual, social get-togethers for groups of students in the same extracurriculars, and a “help offered’ page where older students offered virtual ‘story time’ for younger children, or help with lessons. Recommendations also pertained to aspects of distance learning specifically, that could reduce stress levels among students. Most often, these involved reductions in volume of work teachers assigned to students, flexibility in their expectations while grading, and ensuring that deadlines for major assignments were staggered across departments (e.g., across different days of the week). In some schools, more training and support was needed around technology, as well as the recommendation to adopt a single platform for the whole school (Zoom, Google Hangout, etc.).

Variations across schools

A final comment on findings from this study is that in comparisons of the schools within this study, post hoc analyses showed that Schools 1 and 3 did stand out as having better outcomes than the others. This was seen in relation to anxiety scores and also on several predictor variables, including sharing with adults and concerns heard by the school, as well as learning ability and focus. As noted earlier, Schools 1 and 3 differed from the others in that they had clearly delineated wellness plans, guided by prior in-depth research data on their own schools and involving active participation of all major stakeholders.

Of course, there is no way of knowing if any such interventions had actually catalyzed significant improvements in the Schools 1 and 3 here. Descriptively, 2020 rates of serious distress appeared to be lower than those in 2019, but there are no pre- and post-data, nor any comparison “no-intervention” groups. These caveats clearly explicated, there is perhaps room for cautious optimism regarding the data-driven, school-specific, community-based approach applied. At the least, it could be useful to learn about and document specific new initiatives these two schools had each introduced that they believe may be tied to better all-around functioning in their respective student bodies.

Limitations and future directions

Limitations of this study include its cross-sectional nature – which precludes any conclusions about causality – as well as the sole reliance on self-report measures, many of which were based in single items. The mono-informant method could have led to inflated associations among some constructs. At the same time, it should be noted that multivariate regressions partialled out variance shared between predictors and outcomes due to measurement via self-reports, effectively illuminating links unique to each of the predictors. With regard to the use of single items to assess several predictor variables, it is possible that reliability of measurement would have been higher had multiple items been used. Conversely, the patterns of simple correlations found here, across all schools, generally suggested acceptable validity with significant associations that would be conceptually expected.

Of course, findings of this study cannot be assumed to generalize across developmental periods, and beyond schools such as those examined here. It is possible that trends here do not capture those among younger HAS students in the first two months of school closures, given their less well-developed coping skills and probably greater difficulty in interacting with peers virtually as compared to adolescents. Rates of serious distress as well as the most important predictors of symptoms may well be quite different in other subgroups of students, and, especially in schools with mostly low SES students. For these youth, significant constraints are very likely to arise from a lack of resources needed for distance learning – including good internet services, computers/tablets – as well as limited physical space at home to attend class online, and concerns about family finances given rising unemployment rates during the pandemic. Future research should examine issues addressed here across diverse types of school communities.

Contributions of this work to developmental psychopathology science and practice

Acknowledging such questionable generalizability of findings, some might question the value of studying resilience among HAS students – generally, or specifically during COVID – and there are several pertinent issues in this regard. The first is that this is a nontrivial proportion of youth who are now declared to be “at risk,” but continue to be underrepresented in developmental science (Geisz & Nakashian, Reference Geisz and Nakashian2018). Even just considering schools in the top quartile of US achievement test scores, mathematically, HAS students would represent at least one fourth of the today's children and adolescents. Within HAS contexts, furthermore, there are large numbers of youth who are especially vulnerable given minority status, in terms of family income, ethnicity or sexual orientation. To illustrate, across schools in this study, at least 20% of students were on scholarship and a quarter to almost half were ethnic minorities; youth of color are especially vulnerable to discrimination in overwhelmingly white HAS student bodies (Luthar et al., 2019b).

From a theoretical standpoint, a hallmark of developmental psychopathology is that studies of nonmainstream groups can teach much about normative developmental processes (Cicchetti, Reference Cicchetti1984). Findings from this study indicate that access to high-quality instruction and extracurriculars does offer considerable educational advantages to children, but at the same time, can jeopardize their mental health. In theoretical formulations, the elevated distress documented thus far among HAS students has been posited to from unrelenting achievement pressures (Luthar et al., Reference Luthar, Kumar and Zillmer2019b), and COVID has served as a natural experiment illuminating possible cause–effect links (see Cicchetti, Reference Cicchetti2003). It appears that as distance learning has enforced some release for students from the “I can, therefore, I must” doctrine, they have shown reductions in serious symptoms, overall.

From a practice perspective, the findings carry two clear messages, one pertaining to the children and the second to adults in their lives. While school stakeholders are redefining educational policies and expectations in the coming months, it would be wise to delineate mores that foster the well-being of the whole child, and avoid a return to grueling, unrelenting workloads for students. Similarly, there must be deliberate attention to the well-being of adults both at school and at home, for their own sakes and for the children whom they tend. The stressors of this pandemic will know no bounds by parents’ levels of education, income, or ethnicity. Like parents, teachers in all K-12 schools, regardless of demographics, must receive ongoing support as they tend to their students’ psychological needs through significant life traumas (Luthar et al., Reference Luthar, Kumar and Benoit2019a; Reference Luthar, Kumar and Zillmerb).

Summary

Findings of this study of five high schools further reinforce the conclusion that resilience among adolescents rests, fundamentally, on the quality of their relationships, with important adults in their lives. There was clear evidence that in the eight weeks after school closures in this pandemic, adolescents’ mental health was inextricably linked with parents’ functioning, as perceived by the children themselves. The use of a mixed-methods approach illuminated the importance of support from school adults as well, in addition to dimensions of workload.

Concluding Remarks

Ed Zigler's teachings are deeply embedded in all the research and scholarship reflected within both preceding parts of this article, and closing comments here are focused on the last of five major lessons, following those listed at the outset. Ed encouraged his students to periodically step back and take a “bird's eye” view of our work to ensure that there is ongoing coherence both within and across areas of research and theory, practice and policy. In this concluding section of the paper, I now offer comments from this broader perspective, connecting the different streams of work.

Refining theory: Conceptual issues and prioritization of risk-modifiers

Following our first research paper on resilience (Luthar & Zigler, Reference Luthar and Zigler1991), I remained committed to reexamining salient conceptual, design, and measurement issues, summarizing updates every few years. Epitomizing these efforts was a 2000 article directly addressing the then-growing skepticism of the value of resilience as a scientific construct. This paper addressed salient controversies and points of confusion in this area, with in-depth discussions on operational definitions, approaches to data analyses, and considerations in reporting findings in science, and to the public as well as policy makers (Luthar, Cicchetti, & Becker, Reference Luthar, Cicchetti and Becker2000; for recent discussions, see Infurna & Luthar, Reference Infurna and Luthar2016).

Theoretically, I moved increasingly from detailing different domains of diverse risk and protective factors, to efforts at prioritizing these in terms of potential to bring about meaningful change. Ed often cautioned us students that in psychology, we are trained to consider evidence for many rival hypotheses, but this is at odds with policy makers’ need for succinct summaries of facts. He often quoted these words from a congressman responding to a researcher's presentation: “What this country needs is a one-armed psychologist. You guys are always saying “on the one hand….but on the other hand…”. Zigler (Reference Zigler, McCartney and Phillips1993, p. 11).

As I sought such prioritizing in my own perspective on resilience, I delineated four criteria that might help narrow choices among many ‘rival candidate constructs’ for empirical study. In designing applied research, precedence should be given to those constructs that are (a) recurrently linked with well-being across diverse populations, (b) have meaningful effect sizes, (c) are changeable via interventions that are scalable, and (d) are likely to mobilize other protective influences (in what Rutter (Reference Rutter1987) called positive chain reactions). Whereas my own early writings had afforded equal importance to characteristics of children themselves, families, and communities, it became clear, from multiple experts contributing to a 2003 book, that families had to be first on the list. Logically, this makes sense as parents are the single most proximal and long-term socializing influence for children in general (Luthar & Zelazo, Reference Luthar, Zelazo and Luthar2003).

Further refinements: Within close relationships, which constructs most warrant attention?

Another theoretical refinement was pinpointing critical risk-modifiers within the broad category of parent-child interactions; for most populations of children at risk, most potent is experiencing maltreatment (Luthar & Zelazo, Reference Luthar, Zelazo and Luthar2003; Luthar et al., Reference Luthar, Crossman, Small, Lamb and Garcia Coll2015). Admittedly, the term ‘resilience’ instinctively connotes, for many, an emphasis on positive processes. However, more than any positive aspects of parent–child relationships, chronic abuse and neglect have the most powerful and longstanding effects on children (Luthar & Eisenberg, Reference Luthar and Eisenberg2017; NASEM, 2019). Unfortunately, maltreatment co-occurs with many life adversities commonly studied by resilience researchers, ranging from dire poverty to parent mental illness. Thus, as we think of powerful risk-modifiers that must be considered in working with any vulnerable group, maltreatment must be considered among those that most urgently require attention (Luthar et al., Reference Luthar, Crossman, Small, Lamb and Garcia Coll2015; NASEM, 2019).

The same general principle is true for children's other close relationships; that is, with peers and adults at school. This has become clear from our own recently accumulated data, on over 15,000 students assessed nationally during 2019, on the HAS survey (Authentic Connections, 2019). As we have summarized findings for individual schools, we consistently saw that the strongest unique predictors of symptoms were not positive dimensions such close friendships or support from teachers. Rather, they were usually dimensions of a negative valence, such as victimization by peers, unkindness from teachers, discrimination based on ethnic or sexual minority status, sexual harassment, or perceived tolerance of bullying in the school's climate.

As cumulative findings have informed conceptual views on critical risk-modifiers, in parallel, they have led to ongoing refinements to our measurement in research. To illustrate, the most recent iteration of the HAS Survey (for use in fall 2020 onwards) will include constructs learned to be important from SRS findings during COVID from 45 schools through June 2020. Guided by open-ended data, newly developed questions will allow us to quantitatively assess (and thus track changes over time) in constructs such as students’ worries about family members’ health and finances, and their feelings of loneliness.

Resilience research and social policy: Shifts in emphases

From a “big picture” perspective, there have been two noteworthy shifts in my own thinking about resilience research and social policy; the first is captured within the title of Zigler's classic 1998 paper, “A place of value for applied and policy studies.” In this article, Ed clearly described the value of basic research; put simply, it essential to update knowledge of child development. At the same time, he underscored the need for research designs that yield clear, explicit directions to inform interventions and policies that will be applied in the real world.

Around the turn of the century, I myself joined several colleagues in urging enhanced attention to biological processes (Luthar & Zelazo, Reference Luthar, Zelazo and Luthar2003; Luthar et al., Reference Luthar, Cicchetti and Becker2000), but more recently, have conceptualized these issues in more nuanced terms (Luthar & Eisenberg, Reference Luthar and Eisenberg2017). Of course, there is no question that biomarkers are essential to advance understanding of multilevel influences on children's development; In addition, they can be invaluable in intervention research, when demonstrating benefits of new interventions (e.g., beyond results based on self-reports or observations). What is less clear is how they can be used in large-scale preventive interventions that are not psycho-pharmacological. Echoing Ed's emphasis on pragmatics given limited available funds, the NASEM (2019) report now specifically urges that in prevention-oriented research involving the use of biological assessments (as mediators, moderators, or outcomes), there must be careful elucidation of how these will be used in community-based interventions that have the promise of reaching large numbers of today's vulnerable children and families.

Finally, from the perspective of theory, interventions, as well as policy related to resilience, there has been a noteworthy shift in my thinking about at-risk parents’ role, moving from a focus on skills they must acquire, to specifically prioritizing what caregivers themselves must receive. Conclusions from the previously mentioned 2003 book called for greater focus on “parenting as a dependent variable” (Luthar & Zelazo, Reference Luthar, Zelazo and Luthar2003), recognizing that when children are at-risk, so are their caregivers. In considering potential predictors of this new “dependent variable,” subsequent literature reviews have clearly shown that as with children (and of course, assuming basic needs of food and safety are met), psychological and behavioral resilience among parents rests on their own receipt of ongoing support (Luthar & Eisenberg, Reference Luthar and Eisenberg2017; Luthar et al., Reference Luthar, Crossman, Small, Lamb and Garcia Coll2015).

Contemporary perspectives on this issue too have now come reflect a more specificity beyond the generic notion that caregivers are important. This is seen in three distinct conclusions within the NASEM's (2019) consensus study report. The report notes that, “Promoting resilience in children rests, first, on ensuring the well-being of children's primary caregivers, usually, their mothers, and this requires the mother's ongoing access to strong supportive relationships beyond meeting basic needs for survival” (p. 283). In addition, it underscores gender-specific needs; that is, “There is an urgent need to develop interventions well suited for fathers and other male caregivers; existing approaches that are developed for and tested with women cannot be assumed to generalize …(to) men and fathers who take care of young children” (p. 253). Finally, the report explicitly emphasizes the well-being of educators, noting that as they are expected to support the development of the whole child, they must receive support for their own physical, emotional, and mental health.

What does all this mean during COVID?

In concluding discussions, I return to the research question at the core of this article: How can we maximize childhood resilience during the pandemic? I am mindful here of current directives that applied scientists must move beyond generic statements of what should be done, to delineating specific steps of how to do this, with concrete blueprints or roadmaps for action (Luthar & Eisenberg, Reference Luthar and Eisenberg2017; NASEM, 2019). Based on our team's interactions with over 50 schools between April and June 2020, plus ongoing groups with parents and educators, here are a few concrete steps and issues for consideration.

1. First, we must strictly avoid statements to the public that “most people are resilient” (children or adults). Several months into the pandemic with no clear end in sight, the mental health of all adults is threatened, given ongoing uncertainties of health, jobs, schooling, the economy, and child care. It is inappropriate and unwise for scientists to imply that anyone is immune or invulnerable.

2. Child development experts have called for wealthier nations to provide aid for those less wealthy to ensure physical health, safety, and nutrition (e.g., Yoshikawa et al., Reference Yoshikawa, Wuermli, Britto, Dreyer, Leckman, Lye and Stein2020); yet, resources are becoming stretched everywhere (New York Times, 2020). Thus, as we advocate for national- and international-level systemic changes in policies, local community-level services must be mobilized to provide psychological support through the traumas of COVID-19.

3. It is not enough for scientists to tell people that ‘relationships matter for resilience’; people will need help in setting these relationships in place in their everyday lives. In our own work, we have worked to expand implementation of virtual AC Groups (described earlier in this article) with health care providers beyond the Mayo Clinic, to hospitals in other areas including California and Oregon. In addition, we are now running groups for K-12 counselors and administrators as well as local service providers (both men and women). As these leaders participate in groups, they not only give vital support to each other but also absorb the approach and methods of AC Groups, and then take this offering back to others in their communities.

4. In our ongoing work with schools, we have learned of some creative strategies used by some during the pandemic and have shared these broadly. To illustrate, some schools have created ‘caring committees’, where staff and parents volunteered to ensure ongoing connectedness, in virtual format, for all in the communities. This is done by regular social get togethers for students, and adults (parents and faculty); small group meetings to share strains and provide mutual support; and personal outreach to community members facing special challenges.

5. It must be emphasized that such strategies, resting on mutual support, can be and have been used across socioeconomic settings, as was described at the outset of this article; they do not need large sums of money. Child clinical experts have described many creative ways to enhance support for parents in communities (e.g., connecting via hair-salons, or in supermarkets; see NASEM, 2019). As with AC Groups, some of these strategies can also be explored in virtual format. These are far from perfect solutions, but certainly better than none as we grapple with escalating mental health concerns through this pandemic.

Closing this article describing programmatic research by this group to the present time, I present three quotes, one from Ed himself, as he echoed past president of the American Psychological Association, Ronald Fox (Reference Fox1996). The second is from Dante Cicchetti – for whom Zigler was a mentor as well – and the third from my fellow graduate student Jake Burack and me.

“We owe it to our fellow citizens to devote our massive energy and resources toward the resolution of the problems of a society that is in obvious difficulty.”

– Zigler, Reference Zigler1998, p. 782

“Zigler's work is always conspicuously marked by a love and concern for the people he studies. My bet is that his genuine passion and caring for the topics he researches – the components of his mind – set him apart from most ‘intellects’ and contribute greatly to his spanning dualisms that are too frequently inherent between clinical study of and research into childhood and adult disorders, between basic and applied research, and between developmental psychology and psychopathology. Zigler is an unusually creative compassionate, well integrated human being.”

– Cicchetti, Reference Cicchetti, Zigler and Glick1986, p. xii

“Ed's academic legacy is enshrined by his more than 800 scholarly articles, 43 books and monographs, the numerous social and educational programs that have positively impacted millions of children and families in the United States and around the world, and his generations of students who have contributed to the well-being of children and families in many different ways. This extensive and varied tapestry of accomplishments reflects Ed's world view that success in advocacy, public policy, and social programming is dependent on meticulous science, and that science is only meaningful when it enhances the lives of others.”

– In memoriam: Edward Zigler, 1930–2019

Burack & Luthar, Reference Burack and Luthar2020, p. 411

Supplementary Material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579420001388

Acknowlegements

The authors gratefully acknowledge all students, families, and school leaders from collaborating schools. Sincere thanks as well to Renee Benoit, Lisa Pao, Harrison Tool, and Nicole Zillmer – and especially Nikhil Kumar – for their generous contributions of time and expertise to the new study, and to Jake Burack for his comments on a previous version of this manuscript.

Financial Statement

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of Interest

Support for this work was provided by Authentic Connections. Authors’ roles at Authentic Connections are as follows: Suniya S. Luthar, Co-Founder and Chief Research Officer; Ashley M. Ebbert, Director of Research; Nina L. Kumar, Co-Founder and Chief Executive Officer.