Abstract

Challenging behaviors exhibited by young children negatively affect development and may also prevent children from receiving appropriate education. These behaviors may also hinder positive family interactions and have a significant impact on parents and other family members. Although various parent training approaches exist to increase parents’ capacity to address these challenging behaviors, many parents are reportedly not able to access training due to time and resource constraints. To address inequitable dissemination of information, we developed and piloted the use of the Challenging Behavior Online Modules with 10 parents of children with disabilities. In particular, we examined the feasibility of the Challenging Behavior Online Modules for increasing parents’ knowledge and use of positive parenting practices with their young children. Parents reported satisfaction with the contents and delivery method of the intervention. Implications and directions for future research are also suggested.

Similar content being viewed by others

Many children with autism and other developmental disabilities are reported to have deficits or delays in social-emotional or communication skills, which may lead them to engage in challenging behaviors as communicative attempts (Dunlap & Fox, 2011). Consistent challenging behaviors of young children (e.g., 8 years old and younger) are known to have a significant negative impact on the children’s optimal development (Dunlap et al., 2006; Powell et al., 2006). A widely accepted definition of challenging behavior in the literature is “any repeated pattern of behavior that interferes with or is at risk of interfering with optimal learning or engagement in prosocial interactions” (Smith & Fox, 2003, p. 6). This definition mostly focuses on the interference of children’s behaviors with their environment and learning opportunities rather than the topography of the behaviors.

Furthermore, the impact of challenging behaviors extends beyond the child’s positive development to negatively affect those who interact with them daily (e.g., family members). Parents of children who exhibit challenging behaviors report that their general well-being is negatively affected and that they experience increased stress and social isolation (Doubet & Ostrosky, 2015; Meadan et al., 2010; Neece et al., 2012). When these behaviors are left untreated, children who exhibit challenging behaviors are at a greater risk of being suspended and expelled from schools, as early as preschool. This raises a grave concern as it could have negative consequences for the children and their families (Meek et al., 2020). These experiences and possible outcomes undoubtedly have significant impact on parents’ well-being. Challenging behaviors may also hinder positive parent–child interactions and cause other concerns related to child’s development. For example, suspension and expulsion of children from formal educational settings could also create inequitable access to learning, as children who exhibit challenging behaviors are less likely to receive the same quality and quantity of education as their peers who do not exhibit these behaviors (Meek et al., 2020; Zeng et al., 2020). This may also be exacerbated for marginalized and minoritized children who face inequity based on their ethnicity or immigration status (Gilliam et al., 2016).

The Division for Early Childhood of the Council for Exceptional Children (2017) suggests that challenging behavior must be viewed in the context of multiple factors, including the child’s (1) development, (2) temperament, (3) environment, and (4) sociocultural influences. Considering these factors allows stakeholders (e.g., parents and service providers) to have a better understanding of the ecological components of these behaviors. As they are better informed, stakeholders will more likely engage in effective responses that could prevent or replace challenging behaviors. In such function-based interventions, stakeholders examine the relations between contextual factors of the challenging behaviors. Data on the context of behavior (e.g., when, where, and with whom), antecedent (i.e., what happened just before the challenging behavior), and consequence (i.e., what happened just after the challenging behavior) are repeatedly collected and analyzed to identify the reason (i.e., function) for the challenging behavior (Cooper et al., 2019). Functional assessments are conducted prior to developing an intervention, which informs the function of the behavior. Therefore, stakeholders must first investigate the reason behind the behavior. (Dunlap & Fox, 2011).

Parent Training

The parents’ role is significant in their child's development, especially when a child has a disability or developmental delays and/or exhibits challenging behaviors (López-Liria et al., 2020). Parental stress may increase when parents are uncertain about how to respond to their child’s challenging behaviors (Bearss et al., 2018; Raulston et al., 2019), which could affect the parent–child interaction and can make those interactions more coercive (McIntyre, 2013). Hence, providing training to increase the parents’ understanding of challenging behavior and expanding their capacity to prevent and address challenging behavior could lead to a decrease in parental stress (Argumedes et al., 2018; Fettig et al., 2015) and improve children’s developmental outcomes (Biggs & Meadan, 2018; Reichow et al., 2013; Schreibman et al., 2015). Furthermore, the increased capacity in behavioral principles (i.e., knowledge and skills to address their children’s challenging behaviors) may naturally encourage more positive parenting practices (e.g., limited use of punishment procedures) due to the strong focus on positive reinforcement in applied behavior analysis (ABA). Therefore, it is common to find that parent training often includes interactive components such as “providing information, giving examples, and delivering direct teaching” (Meadan et al., 2017, p. 254). In addition, providing training with nonspecialists (e.g., parents) who are not formally trained to deliver interventions with children with disabilities have been gaining more support in the literature (Reichow et al., 2013).

Despite the importance of providing training with parents, there is an issue of equity of access to care for parents of children with and without disabilities. It is widely recognized that parents who live in low-resourced communities (e.g., rural areas in the United States) do not have the same level of access to professional resources when compared to other parents (Heitzman-Powell et al., 2014; Maye et al., 2021; Meadan et al., 2013). This limited access inevitably leads to long delays in receiving needed support, including diagnosis, treatment, and education, which is known to hinder optimal development, especially of children with disabilities (Vivanti et al., 2014). Given the significant roles of parents in the developmental outcomes of young children, it is crucial to examine and develop accessible programs that could help increase parental knowledge and capacity to appropriately respond to their children’s challenging behaviors at home regardless of their other access to services.

Telepractice

Research has improved and diversified intervention delivery methods for parents to gain access to evidence-based practices (EBP) regardless of their situations or geographical locations. One innovative way of delivering EBP is the use of telepractice technology. With the recent technological advances, there is a growing body of telepractice-related literature. This literature reports on the effectiveness of training on behavioral principles using telepractice, in particular in increasing the parents’ capacity to deliver EBP with their children who exhibit challenging behaviors. For example, Ferguson et al., (2019) conducted a systematic review of 28 studies that utilized telepractice technology to train stakeholders of children with autism. The review revealed that 86% (N = 194) of the parent participants increased in their knowledge or skills in using behavioral interventions following telepractice. The review also indicated that telepractice interventions were mostly effective. Therefore, the researchers concluded that telepractice may be an acceptable model for providing training to stakeholders to use ABA interventions.

Previous literature on parent training that utilized telepractice demonstrated the effectiveness of telepractice and its promising features to increase parents’ capacity. For example, Heitzman-Powell et al. (2014) developed and evaluated a training and coaching program, Online and Applied System for Intervention Skills, for parents of children with autism who live in rural areas of the United States. This program included a combination of web-based instructional video modules and synchronous coaching through telepractice technology. Although there was a small number of parents who completed the study (N = 7), these parents reported high levels of satisfaction with the intervention. The parents also indicated that the travel time for them was significantly reduced with the utilization of telepractice. In another study, Turgeon et al. (2021) used interactive web-based training that consisted of five video modules on behavioral interventions. The researchers conducted a randomized controlled trial with 26 participants. The modules included topics related to basic behavior intervention such as understanding challenging behaviors, antecedent-based interventions, and teaching replacement behaviors. In this study, the researchers reported that parents in the intervention group reported using more behavioral strategies that were covered in the modules, and these parents observed lower frequency and severity of their children’s challenging behaviors when compared to the parents in the waitlist control group. However, the researchers also noted that there was a significant attrition rate (45%; 21 out of 47 parents), which may suggest that the parents may benefit from additional support to participate in telepractice research.

Although prior studies have demonstrated several benefits of parent education programs, it may be necessary to examine the isolated effect and feasibility of low-dosage online parent training compared to a more comprehensive parent education approach. For example, Heitzman-Powell et al. (2014) included not only training via telepractice (i.e., providing information), but also extensive coaching sessions that required participants to physically travel to the regional sites to receive coaching. In addition, although the researchers evaluated the gains in knowledge and skills, they did not evaluate the impact of training alone, and did not examine its effects on the participants’ parenting practices. In addition, although Turgeon et al. (2021) used online training alone, their focus was the frequency and severity of children’s challenging behavior after the parents received the online training, and they did not further investigate the feasibility of the program using qualitative methods.

When developing a program to increase the parents’ capacity, it is not enough to evaluate the accessibility of the program; it is also essential to understand parents’ perspectives related to the program’s goals, procedures, and outcomes (i.e., social validity). The purpose of assessing the social validity of a program is to determine how the program relates to parents’ values and priorities (Wolf, 1978). If parents do not perceive the goals and outcomes of the program as important to their families or do not perceive the procedures used in the program as feasible, it is likely that they will not use and benefit from the program. In addition, feasibility of a program must be evaluated by the stakeholders first to determine its potential effects on a larger population. However, there is a relatively limited number of studies that focus on providing asynchronous training with parents in understanding and addressing challenging behavior. Given the difficulties associated with telepractice synchronous coaching, such as scheduling and prolonged parental engagement, it is imperative to examine how accessible online modules that can be completed at the parents’ unique paces help increase their skills and knowledge to respond to their children’s challenging behaviors. Therefore, this study focused primarily on describing the development of the Challenging Behavior Online Modules (CBOM) for parents of young children who exhibit challenging behaviors at home and describing the acceptability and feasibility of using these modules to increase parents’ knowledge and positive parenting practices.

Method

Development of the Modules

The CBOM was developed with the purpose of increasing the parents’ knowledge in behavioral principles and positive parenting practices based on the ABA literature (e.g., Cooper et al., 2019). These modules consisted of six didactic PowerPoint presentations that were recorded with narration in video formats. As the modules were made for parents of young children with challenging behavior, they were developed with an intention to be parent friendly and easy to understand. For example, we minimized the use of jargon when describing behavioral principles (e.g., reinforcement). When the use of technical terms was unavoidable, they were followed by a detailed explanation and demonstrating examples. The contents of the modules were determined based on the clinical and content expertise of the first and third authors, who are both board certified behavior analysts with many years of experience of conducting research and providing services to families of children with autism. After an outline of each module was drafted, it was reviewed and revised by the research team that includes two faculty members and several doctoral students in special education who had diverse backgrounds both in behavior analysis and special education. The final modules were also reviewed by two additional behavior analysts and two parents of children with delays/disabilities who were not affiliated with this study. These stakeholders were identified by the research team members. The feedback was discussed by the team members and changes to the modules were made, as appropriate.

Each module ranged in duration from 6 to 12 min (M = 9 min) because they were intended to be brief and succinct to facilitate convenient learning for the parents by consciously reducing time demands. See Figure 1 for an example slide. Module 1 provided an overview of the series, what behavior is, and the process of learning through reinforcement. Module 2 discussed different functions of behavior, and Module 3 included specific strategies to identify functions and behavior changes through consequences. Module 4 described various antecedent-based interventions that parents can use at home. Modules 5 and 6 discussed reinforcement-based interventions, including functional communication training and token economy. See Table 1 for more detailed information on each module. Throughout the modules, parents were given specific, real-life examples that they may encounter with their children. For example, scenarios for a child’s challenging behavior were included along with how to identify the functions and implement reinforcement-based strategies (e.g., functional communication training). These examples were added with the intention to provide specific, practical strategies to parents, which focused primarily on increasing parents’ knowledge of behavioral principles. Participants were encouraged to practice these skills at home with their own children; however, their mastery of skills was not monitored given the format of the intervention.

The adult learning theory (ALT; Knowles et al., 2014) served as the main framework during the development of the modules. In ALT, training is one of the methods to effectively transfer knowledge (Joyce & Showers, 2002), which initially includes the acquisition of knowledge and skills (Fixsen et al., 2005). The modules also incorporated examples of EBPs to prevent and address challenging behavior and multiple principles of ALT to facilitate the acquisition of the modules’ content by including introduction, illustration, practice, evaluation, and mastery (Trivette et al., 2009). See Table 2 for more detailed information.

Participants

Upon approval from the Institutional Review Board, participants were recruited through local, state, and regional centers, as well as social media platforms (i.e., Facebook) in particular for parents and service providers (e.g., doctors, parent centers, behavior analysts, and therapists). The inclusion criteria for participation were that the parents had (1) a child under the age of 8 with a diagnosed disability or developmental delay who exhibited challenging behavior and (2) the necessary technology to complete the online training and assessments (e.g., smartphone, computer, or tablet). During the initial screening, consenting parents were asked to identify their children’s diagnoses and to provide information about their children’s challenging behaviors. Upon completion of the screener, participants were emailed with further directions if they met all the inclusion criteria. Participants were given $20 in gift cards for their participation in the training and an additional $10 if they participated in individual posttraining interview.

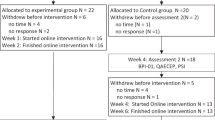

A total of 28 interested individuals completed the eligibility screener. Of these individuals who completed the screener, 27 met inclusion criteria and received access to the online modules. Of the 27 individuals, 10 never accessed the online platform, and 7 accessed the online platform but did not complete any activities (e.g., assessments and modules). Overall, a total of 10 parents (9 mothers and 1 father) of children with disabilities who exhibited challenging behaviors participated in this study (see Table 3); four participants completed the follow-up interviews after the completion of the study. All parents had attended at least some college and were predominately white (n = 8). All 10 participants were from the United States. In particular, eight participants were from the Midwest, one participant was from the East Coast, and one participant was from the Southwest. It is noteworthy that the self-reported measure for parental stress (Parenting Stress Index, Fourth Edition, Short Form [PSI-4-SF], Abidin, 2012) revealed that 5 out of 10 parents had stress levels within the “clinically significant” range. Children of parent participants were between the ages of 2 and 7 years (M = 4.7 years old) with a diagnosed disability. The reported challenging behaviors consisted of mostly externalizing behaviors, such as aggression, yelling, tantrums, screaming, and self-injurious behaviors. Participants also provided information related to the routines in which challenging behaviors occur most frequently, the topography of the behaviors, and how these behaviors affect children. In terms of the frequency (i.e., never, rarely, sometimes, frequently, very frequently) and intensity (i.e., very mild, mild, moderate, somewhat severe, very severe) of the behaviors, most parents reported that these challenging behaviors occurred frequently (60%, n = 6) or very frequently (20%, n = 2) during the day and that these behaviors were moderate (50%, n = 5) to somewhat severe (50%, n = 5). All parents reported that these challenging behaviors at least moderately affected them and other family members (90%, n = 9).

Measures and Procedure

Participants completed the pretraining assessments and questionnaires, the CBOM, and posttraining assessments and questionnaires. Some participants also participated in a semi-structured, posttraining interview with the researchers. A learning management system (LMS; i.e., Moodle™) was utilized to aid the process of completing all aspects of the study. After their eligibility to participate was confirmed, participants were given access to the LMS and were provided with instructions to navigate the LMS to complete each component. Each participant was given 3 weeks to complete all three parts of the study (i.e., pretraining measures, modules, and posttraining measures). Weekly reminders to complete the modules were sent via email and text messaging based on the participants’ preferred mode of communication, and participants reached out when they needed assistance with technology, including access to specific modules and navigating the LMS. Following the completion of the CBOM, a follow-up email was sent to invite participants to participate in the posttraining interviews.

Pretraining Measures

Participants began by completing two pretraining measures: (1) Parent Knowledge Assessment (PKA; Lee et al., 2021), and (2) the Parenting Young Children (PARYC; McEachern et al., 2012). The PKA is a researcher-developed measure for knowledge assessment for behavioral principles, which included 30 multiple-choice questions that corresponded with the subsequent modules in the following part of the study. It included five questions for each of the six modules, and participants had one attempt with unlimited time to complete this assessment on the LMS. It has been used with diverse populations, such as parents of children with disabilities in Korea and Paraguay, and its Cronbach’s alpha was reported as good (.73; Lee et al., 2021). The PARYC is a self-report measure designed to address parenting behaviors within three sections: (1) sharing fun and supporting good behavior, (2) setting rules and following through, and (3) planning ahead with your child (McEachern et al., 2012). The PARYC has 21 items with 7 items or practices in each subscale. Within each subscale there were seven items and participants had to respond to each item by (1) rating, on a scale of 1–7 (1 = not at all; 7 = most of the time), how often they used the practice with their children in the past month; (2) reporting (Yes or No) if this practice was a problem for them, and (2) indicating if they would like to do things differently related to each item. The Chronbach’s alpha for all three subsections was reported as good (.78, .79, and .85, respectively; McEachern et al., 2012). Upon completion of both pretraining measures, participants were granted immediate access to the next step of the training, the six online modules.

Modules

Participants completed all six modules in an order. When participants finished watching each video module, they were automatically given access to the posttraining assessment for understanding the contents of each module on the LMS, which were the same questions from the PKA at pretraining. This served as a prerequisite activity before gaining access to the next module regardless of the participant’s score, and the PKA was administered upon completion of each module to ensure participants’ timely completion. This continued until all six modules were completed. In addition, administering the PKA and PARYC both at pre- and posttraining enabled us to compare the results and to examine efficacy of the CBOM.

Posttraining Measures

When all six video modules were completed, the posttraining measures became available, which included the (1) PARYC, and (2) posttraining questionnaire. Like the pretraining measures, the PARYC was completed in the same format as the LMS. The posttraining questionnaire was used to inquire about the social validity of the study and included Likert-style (n = 11), yes or no (n = 1), and short answer (n = 4) questions. Likert-type questions included questions for the parent about the frequency, intensity, duration, and topography of the child’s behavior. These were followed by questions about the impact of the child’s behavior on themselves, the parent(s), other family members, and the community. Questions mostly focused on the impact, helpfulness, and feasibility of the CBOM.

Posttraining Interviews

The purpose of the posttraining interviews was to further explore participants' perceptions related to the efficacy, satisfaction, and impact of the modules. The interviews were semi-structured with three general questions and 12 follow-up questions as a guide. The questions were generated largely based on the social validity framework by Wolf (1978). Four participants agreed to participate in the interview. The interviews ranged from 18 to 24 min (M = 21 min) and were recorded and transcribed verbatim by an external service for analysis purposes. Two members from the research team implemented a priori coding of the qualitative data. The codes were developed ahead of time to categorize the interview responses under the three aspects of social validity, goals, procedures, and outcomes (Kazdin, 1977).

Results

Knowledge Assessment

The pretraining knowledge assessment scores were compared to the posttraining scores to evaluate changes and to draw conclusions about the CBOM both overall and at the individual training module level. Data for each module are shown in Figure 2, and Figure 3 illustrates score comparison for each participant across all modules. Overall, there was an increase in knowledge between the pretraining knowledge assessment to the posttraining knowledge assessment. In the pretraining phase, the percentage of correct responses ranged between 56.7% and 83.3% (M = 68.3%), and the percentage of correct responses increased to range between 63.3% and 96.7% (M = 86.4%) in the posttraining phase. Participants had the largest increase in the percentage of correct responses in Module 1 (increase of 44%) then followed by Module 4 (increase of 38%). Participants had a 28% increase in correct responses in Modules 5 and 6, followed by an 18% increase in Module 3, and an increase of 10% in correct responses in Module 2. Overall, participants' knowledge assessment scores increased from pretraining to posttraining assessments with an average growth of 24%.

PARYC

Supporting Good Behavior

In the pretraining assessment, when asked how often they used the seven items on the subscale of supporting good behavior in the past month, participants reported on a scale of 1 to 7 (4 = sometimes), a mean of 4.41. At the posttraining assessment, the mean on this subscale slightly increased to 4.71. The participants reported in both pre- and posttraining assessments that they least frequently “involved the child in chores” and most frequently “noticed and praised the child’s good behavior.” The largest change from pre to posttraining assessments was in the practice of involving the child in chores. When participants were asked if the items in this subscale were problematic for them, parents reported in the pretraining assessment that 33% of the items were problematic, which was comparable to the posttraining assessment that 29% of the items were problematic. In both pre- and posttraining assessments, the participants indicated that they had the most difficulty in teaching their children new skills. Finally, most of the participants reported that teaching their children new skills was the practice they would have liked to change or alter the most. This was evident in both the pre- and posttraining assessments across all subscales.

Setting Limits and Following Through

For the subscale of setting rules and following through, participants reported that they used the items with a mean of 4.2 on a scale of 1 to 7 in the pretraining assessment and a mean of 4.36 in the posttraining assessment. There were no noticeable differences in the rating of the items within the scale and across timepoints (i.e., pre- and posttraining assessment). In addition, participants reported that 63% of the items were problematic for them at the pretraining assessment, which decreased to 56% at the posttraining assessment. In the pretraining assessment, participants found the items of “speaking calmly to the child” and “explaining what they want their child to do” to be the most difficult practices to implement. After the training, participants reported that the items “sticking to the rules” and “making sure the child is following the rules” were the most difficult practices on the subscale. When asked which practices they would have liked to change or do differently, participants indicated in the pretraining assessment that they would like to speak calmly to their children and in the posttraining assessment the practice they most wanted to change was making sure the child is following the rules.

Planning Ahead with Your Child

For the last scale in the assessment that included items related to proactive parenting, participants reported they used the items with a mean of 4.59 on a scale of 1 to 7 (4 = sometimes) in the pretraining assessment and a mean of 4.65 in the posttraining assessment. The largest change in the rating of the items between the pre- and posttraining assessments was in the item of "preparing the child for a challenging situation" with a rating of 4.5 in pretraining and a rating of 3.8 in posttraining. Participants indicated about 37% of the items were problematic for them in the pretraining assessment, which decreased to 33% in the posttraining assessment. In the pretraining assessment, the practice the participants wanted to change the most was “making games out of everyday tasks so the child will follow through,” and the practice participants wanted to change the most in the posttraining assessment was “preparing the child for a challenging situation.”

Social Validity

All parent participants completed a short questionnaire after completing the CBOM related to their experience, and four parents also participated in a short interview at the end of the study. Overall, all parent participants indicated high satisfaction with the CBOM. In the questionnaire, one parent wrote, “The program is very useful. I think all parents receiving services through therapy centers should complete such modules to better understand and modify their child’s challenging behaviors.” In the interview, a parent stated, “I thought that they [the modules] were really great, especially for parents trying to navigate some challenging issues with their children.” In particular, parents expressed satisfaction with the contents of the modules and the concepts included, the simplicity of the language used to describe the information, and the overall format of delivery and accessibility of the CBOM (e.g., six short online modules). When asked in the questionnaire to rate, between very low (1) to very high (5), the level of agreement with statements about the CBOM, parents reported (1) an average of 4.4 on overall satisfaction with the program, (2) an average of 4.6 on the relevance of the information included in the CBOM to their experiences at home, and (3) an average of 4.6 on the overall feasibility.

Although parents indicated high satisfaction with the CBOM, they also described a few challenges including issues related to (1) specific aspects of the training delivery (e.g., using the LMS and clarity of the knowledge assessment questions) and (2) the ability to implement the described strategies at home with their children. When discussing the training delivery format, one parent stated, “I couldn’t move on to the evaluation because evaluation has to happen when you complete all of the modules. I realized ‘. . . Oh, yeah. I've got to physically check mark them done so I'd move on.’ Once I figured that out, it was fine. It just wasn't intuitive.” Other parents described the difficulties in implementing the strategies described in the modules. One parent explained, “being able to implement, being able to come up with a token system and a rewards menu and all that while working full-time and watching the kids and all the housework; it's overwhelming without any help.” Parents suggested some improvements to the LMS that hosts the modules, including making navigation clearer and to provide additional support to parents with the implementation of the strategies as a follow-up for watching the modules.

When discussing the outcomes of the CBOM, all parent participants indicated in the questionnaire that watching the online modules affected the way they interacted with their children in the home environment. The participants provided examples for how watching the modules changed their behavior. One parent wrote in the questionnaire, “I have realized that many of my son's tantrums probably are attention related and trying to calm him down only fuels the fire.” Another parent reported in the interview,

Training really helped me to remember to stop and kind of analyze what was going on, and try to figure out what that antecedent was, which was really helpful for trying to proceed through the B [behavior] and the C [consequence], and attempt to modify the behavior.

Parent participants also reported in the interviews that watching the modules and, in turn, changing their behavior affected their children. One parent stated,

We did definitely see a reduction in behaviors, which was awesome. It doesn't work 100% of the time because sometimes I cannot figure out the antecedent, so, of course, that continues to be a work in progress, but we have definitely seen our kids' aggressive behaviors go down. They seem to be less frustrated.

The CBOM also had an impact on the family as a whole: “It made us just enjoy each other's company more, honestly, which is really, really nice.” Another parent explained,

I think now we're much better able to relax and enjoy each other. So, we're able to play together more and stop that feeling of hypervigilance. I used to feel like I had to always be monitoring them and waiting for something bad to happen. And now we're able to let that guard down a little bit, and just interact and have fun and play. It's a much more pleasant feeling.

Parents also recommended that other parents with similar situations have access to the training. One parent summarized this.

We're super busy and we don't have time to waste on things that don't really have a big payoff. And I think the payoff from the time investment in this program is huge, and I wouldn't recommend it to other parents if I didn't feel that way. And I think it's so important, especially for those that do have problematic behaviors. I think it's so important to figure it out as soon as possible before it makes a longer lasting problem in the family unit. I think it's easy to understand and I think it's easy to implement, and I think it's super helpful. So, I would definitely recommend it.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to examine the acceptability and feasibility of the online CBOM to increase parents’ knowledge and positive parenting practices with their young children with disabilities who engage in challenging behavior. The results from the pre- and posttraining measures indicate that there were increases in participants' knowledge of behavioral principles and the reported use of positive parenting practices. All participants scored higher at posttraining measures across all six online modules in assessing their knowledge, and they had fewer difficulties in using positive parenting practices as measured by the PARYC. Other researchers have reported that online training modules could lead to an increase in parents’ and professionals' knowledge of effective strategies (Ingersoll et al., 2016; Meadan et al., 2016, 2020; Neely et al., 2016). This study extends the findings from other studies by exploring the reported impact of online training modules on parents’ use of positive parenting practices.

Overall, participants perceived the CBOM to be socially valid and reported high satisfaction with the goals, procedures, and outcomes of the online training. They spoke highly of the feasibility of receiving training via online modules, despite some minor issues with technology, which suggests that such delivery models may be used effectively to disseminate EBPs with parents with necessary adaptations. In prior literature, researchers have highlighted the importance of technology in telepractice training and called researchers to ensure participants are equipped with such technology to avoid issues related to connectivity (Lerman et al., 2020). It should be noted that a few parents also expressed some challenges with using necessary technology to access the training, which indicates that it is necessary to ensure technology does not prevent the parents’ access to online learning of EBPs. Considering that most parents have very busy schedules, short and focused training modules that can be accessed at their convenience may have contributed to the perceived feasibility of the CBOM. In addition, the asynchronous format of intervention delivery may have increased feasibility. Increasing the parents’ knowledge and building their capacity to prevent and address their children’s challenging behavior could have important impact on the parents (e.g., feeling of empowerment and self-confidence), the children (decrease in challenging behavior and increase in social-communication skills), and the family overall quality of life (Dunst et al., 2007).

However, some participants indicated that they needed additional, individualized support to implement the strategies at their homes with their children. Although the modules include examples of how to conduct certain strategies, the participants’ responses indicate that there is a need to expand on the unilateral dissemination of information, and many researchers have included components of synchronous interactions with the participants (e.g., coaching; Bearss et al., 2018). This is not surprising given the extent of literature that reports that both training and coaching are needed to support changes in both knowledge and practices (Ingersoll et al., 2016; Meadan et al., 2016, 2020; Snodgrass et al., 2017).

Researchers report high acceptability and feasibility of an intervention delivery model that utilizes technology to disseminate information to parents of young children with disabilities and challenging behavior (Heitzman-Powell et al., 2014; Turgeon et al., 2021). In these studies, however, the researchers primarily utilized training modules that are significantly lengthier than what was used in the present study. In addition, prior studies incorporated some type of coaching (i.e., synchronous interaction between researcher and parent to provide feedback). Although coaching is an effective way to increase parents’ capacity, it is also inherently time-consuming as it requires more effort from parents, and these may not be feasible for certain parents. Even accessing the lower-effort modules used in the current study could have required too much time from parents, which may have contributed to our attrition rate. Although 27 participants voluntarily signed up to participate in this study, only 10 participants completed the study. Similar attrition rates were reported in other parent training literature (e.g., Turgeon et al., 2021). This may suggest that not all parents are able to complete their participation in online research for various reasons, including time commitment or challenges related to COVID-19 pandemic. In addition, it could be also related to the timing of when this study occurred, which was when many social distancing requirements were put in place. However, no participant provided a reason for withdrawing from the study.

Furthermore, synchronous interactions also require participants to be substantially more proficient in using technology (e.g., recording and uploading videos, and live video conferencing), which may be a barrier for some parents in lower-resourced communities. The current study extends the previous literature by examining changes in parents’ knowledge and positive parenting practices using a series of short modules with parent-friendly language that may be easily accessible. Another contribution of this study is the data from the post intervention questionnaire and interviews that provided additional information on the social validity of the CBOM. The participants’ qualitative input provided much detailed feedback and implications for future studies.

Limitations and Implications

Despite the promising findings related to the acceptability and feasibility of the online training modules, there are several notable limitations presented in this study. First, as a nonexperimental pilot study that examined newly developed online training modules with no control group, there was a small number of parents who participated in this study (N = 10). Therefore, caution is merited when interpreting and generalizing the findings of this study, and further investigation with a larger number of participants is needed. Furthermore, the data presented were only descriptively analyzed due to limited statistical power, and we hypothesize that the small number of participants was largely contributed to by the COVID-19 pandemic that affected the lives of potential participants. However, in a randomized controlled trial involving a larger number of participants using CBOM, Lee et al. (2021) reported significant changes in participants’ knowledge of behavioral principles and self-reported parenting practices. In addition, there were no observational data on parents’ fidelity of implementation of the behavioral strategies they learned from the modules, future research therefore should examine parents’ skill acquisition using a similar format. Although it is beyond the scope of this study to detect differences of parent–child interaction at pre- and postintervention, future studies should include components of behavioral observations to complement parents’ reports. Moreover, all participants had at least some college experiences, most of the participants were white (80%), and most reported their monthly household income being above $6,000 (70%). This is not representative of the rapidly changing demographics of the United States, which warrants further investigation of how researchers may reach families from diverse backgrounds (e.g., culturally and linguistically diverse families with lower level of education). Although the CBOM provided appropriate examples for children under the age of 8, there should be more considerations related to age-appropriate application of behavior-analytic strategies. Due to the limited scope of CBOM, this may also be described as video modules with competency checks rather than “modules,” which may imply additional components such as opportunities to role-play or practice of the skill.

This study also offers some implications for providing training on behavioral principles to parents of children with developmental disabilities. Although such “one-time” training may not drastically alter the parents’ behaviors, it may be used as a preventative form of a universal training to build the capacity of parents with young children. Researchers should also examine the combined effects of training and coaching to enhance the dissemination in future studies, as these two approaches to adult learning are shown to be effective when used in combination (Meadan et al., 2017; Trivette et al., 2009). Lastly, the conclusion of this intervention delivery model of using online training modules may encourage future researchers to increase parents’ capacity in different areas, such as promoting children’s social-communication development, especially for populations who may not have access to similar resources in their communities. A larger scale-up study with more rigorous experimental design, such as a randomized controlled trial with multiple timepoints is warranted to examine the efficacy of such a model of intervention delivery with diverse populations.

References

Abidin, R. R. (2012). Parenting stress index (4th ed.). PAR.

Argumedes, M., Lanovaz, M. J., & Larivée, S. (2018). Brief report: Impact of challenging behavior on parenting stress in mothers and fathers of children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism & Developmental Disorders, 48(7), 2585–2589. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-018-3513-1

Bearss, K., Burrell, T. L., Challa, S. A., Postorino, V., Gillespie, S. E., Crooks, C., & Scahill, L. (2018). Feasibility of parent training via telehealth for children with autism spectrum disorder and disruptive behavior: A demonstration pilot. Journal of Autism & Developmental Disorders, 48(4), 1020–1030. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-017-3363-2

Biggs, E. E., & Meadan, H. (2018). Early communication interventions for young children with intellectual and developmental disabilities: The roles of natural communication partners. International Review of Research in Developmental Disabilities, 55, 1–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.irrdd.2018.08.005

Cooper, H., Hedges, L. V., & Valentine, J. C. (Eds.). (2019). The handbook of research synthesis and meta-analysis. Russell Sage Foundation.

Division for Early Childhood. (2017). Position statement on challenging behavior and young children. https://challengingbehavior.cbcs.usf.edu/docs/DEC_PositionStatement_ChallengingBehavior.pdf

Doubet, S. L., & Ostrosky, M. M. (2015). The impact of challenging behavior on families: I don’t know what to do. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 34(4), 223–233. https://doi.org/10.1177/0271121414539019

Dunlap, G., & Fox, L. (2011). Function-based interventions for children with challenging behavior. Journal of Early Intervention, 33(4), 333–343. https://doi.org/10.1177/1053815111429971

Dunlap, G., Strain, P. S., Fox, L., Carta, J. J., Conroy, M., Smith, B. J., Kern, L., Hemmeter, M. L., Timm, M. A., Mccart, A., Sailor, W., Markey, U., Markey, D. J., Lardieri, S., & Sowell, C. (2006). Prevention and intervention with young children's challenging behavior: Perspectives regarding current knowledge. Behavioral Disorders, 32(1), 29–45. https://doi.org/10.1177/019874290603200103

Dunst, C. J., Trivette, C. M., & Hamby, D. W. (2007). Meta-analysis of family-centered helpgiving practices research. Mental Retardation & Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews, 13(4), 370–378.

Ferguson, J., Craig, E. A., & Dounavi, K. (2019). Telehealth as a model for providing behaviour analytic interventions to individuals with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review. Journal of Autism & Developmental Disorders, 49(2), 582–616. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-018-3724-5

Fettig, A., Schultz, T. R., & Sreckovic, M. A. (2015). Effects of coaching on the implementation of functional assessment-based parent intervention in reducing challenging behaviors. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 17(3), 170–180. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098300714564164

Fixsen, D. L., Naoom, S. F., Blase, K. A., Friedman, R. M., & Wallace, F. (2005). Implementation research: A synthesis of the literature. University of South Florida, Louis de la Parte Florida Mental Health Institute, The National Implementation Research Network (FMHI Publication #231). https://nirn.fpg.unc.edu/sites/nirn.fpg.unc.edu/files/resources/NIRN-MonographFull-01-2005.pdf

Gilliam, W. S., Maupin, A. N., Reyes, C. R., Accavitti, M., & Shic, F. (2016). Do early educators’ implicit biases regarding sex and race relate to behavior expectations and recommendations of preschool expulsions and suspensions. Yale University Child Study Center, 9(28), 1–16.

Heitzman-Powell, L. S., Buzhardt, J., Rusinko, L. C., & Miller, T. M. (2014). Formative evaluation of an ABA outreach training program for parents of children with autism in remote areas. Focus on Autism & Other Developmental Disabilities, 29(1), 23–38. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088357613504992

Ingersoll, B., Wainer, A. L., Berger, N. I., Pickard, K. E., & Bonter, N. (2016). Comparison of a self-directed and therapist-assisted telehealth parent-mediated intervention for children with ASD: A pilot RCT. Journal of Autism & Developmental Disorders, 46(7), 2275–2284. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-016-2755-z

Joyce, B. R., & Showers, B. (2002). Student achievement through staff development (3rd ed.). Association for Supervision & Curriculum Development (ASCD).

Knowles, M. S., Holton, E. F., & Swanson, R. A. (2014). The adult learner: The definitive classic in adult education and human resource development. Routledge.

Lee, J. D., Meadan, H., & Xia, Y. (2021). A pilot RCT: Effects of self-paced online modules on behavior management in Korean caregivers of children with disabilities. [Unpublished manuscript].

Lerman, D. C., O’Brien, M. J., Neely, L., Call, N. A., Tsami, L., Schieltz, K. M., Berg, W. K., Graber, J., Huang, P., Kopelman, T., & Cooper-Brown, L. J. (2020). Remote coaching of caregivers via telehealth: Challenges and potential solutions. Journal of Behavioral Education, 29(2), 195–221. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10864-020-09378-2

López-Liria, R., Vargas-Muñoz, E., Aguilar-Parra, J. M., Padilla-Góngora, D., Mañas-Rodriguez, M. A., & Rocamora-Pérez, P. (2019). Effectiveness of a training program in the management of stress for parents of disabled children. Journal of Child & Family Studies, 29, 964–977. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-019-01665-5

Marleau, B., Lanovaz, M. J., Gendron, A., Higbee, T. S., & Morin, D. (2019). Using interactive web training to teach parents to select function-based interventions for challenging behaviour: A preliminary study. Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability, 44(4), 492–496. https://doi.org/10.3109/13668250.2018.1464281

Maye, M., Boyd, B. A., Martínez-Pedraza, F., Halladay, A., Thurm, A., & Mandell, D. S. (2021). Biases, barriers, and possible solutions: Steps towards addressing autism researchers under-engagement with racially, ethnically, and socioeconomically diverse communities. Journal of Autism & Developmental Disorders, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-021-05250-y

McEachern, A. D., Dishion, T. J., Weaver, C. M., Shaw, D. S., Wilson, M. N., & Gardner, F. (2012). Parenting Young Children (PARYC): Validation of a self-report parenting measure. Journal of Child & Family Studies, 21(3), 498–511. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-011-9503-y

McIntyre, L. L. (2013). Parent training interventions to reduce challenging behavior in children with intellectual and developmental disabilities. International Review of Research in Developmental Disabilities, 44, 245–279. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-401662-0.00008-7

Meadan, H., Halle, J. W., & Ebata, A. T. (2010). Families with children who have autism spectrum disorders: Stress and support. Exceptional Children, 77(1), 7–36. https://doi.org/10.1177/001440291007700101

Meadan, H., Meyer, L. E., Snodgrass, M. R., & Halle, J. W. (2013). Coaching parents of young children with autism in rural areas using internet-based technologies: A pilot program. Rural Special Education Quarterly, 32(3), 3–10. https://doi.org/10.1177/875687051303200302

Meadan, H., Snodgrass, M. R., Palomo, I., Amenta, C. G., & Halle, J. W. (2017). A framework for defining contextual features of training and coaching practices. Exceptionality, 25(4), 253–269. https://doi.org/10.1080/09362835.2016.1196451

Meek, S., Smith, L., Allen, R., Catherine, E., Edyburn, K., Williams, C., Fabes, R., McIntosh, K., Garcia, E., Takanishi, R., Gordon, L., Jimenez-Castellanos, O., Hemmeter, M. L., Gilliam, W., & Pontier, R. (2020). From the early years to the early grades. https://childandfamilysuccess.asu.edu/sites/default/files/2020-07/CEP-report-071520-FINAL.pdf

Neece, C. L., Green, S. A., & Baker, B. L. (2012). Parenting stress and child behavior problems: A transactional relationship across time. American Journal on Intellectual & Developmental Disabilities, 117(1), 48–66. https://doi.org/10.1352/1944-7558-117.1.48

Neely, L., Rispoli, M., Gerow, S., & Hong, E. R. (2016). Preparing interventionists via telepractice in incidental teaching for children with autism. Journal of Behavioral Education, 25(4), 393–416. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10864-016-9250-7

Powell, D., Dunlap, G., & Fox, L. (2006). Prevention and intervention for the challenging behaviors of toddlers and preschoolers. Infants & Young Children, 19(1), 25–35. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001163-200601000-00004

Raulston, T. J., Hieneman, M., Caraway, N., Pennefather, J., & Bhana, N. (2019). Enablers of behavioral parent training for families of children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Child & Family Studies, 28(3), 693–703. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-018-1295-x

Reichow, B., Servili, C., Yasamy, M. T., Barbui, C., & Saxena, S. (2013). Non-specialist psychosocial interventions for children and adolescents with intellectual disability or lower-functioning autism spectrum disorders: A systematic review. PLoS Med, 10(12), e1001572. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001572

Schreibman, L., Dawson, G., Stahmer, A. C., Landa, R., Rogers, S. J., McGee, G. G., Kasari, C., Ingersoll, B., Kaiser, A. P., Bruinsma, Y., McNerney, E., Wetherby, A., & Halladay, A. (2015). Naturalistic developmental behavioral interventions: Empirically validated treatments for autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism & Developmental Disorders, 45(8), 2411–2428. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-015-2407-8

Smith, B., & Fox, L. (2003). Systems of service delivery: A synthesis of evidence relevant to young children at risk of or who have challenging behavior. Center for Evidence-Based Practice: Young Children with Challenging Behavior. www.challengingbehavior.org

Snodgrass, M. R., Chung, M. Y., Biller, M. F., Appel, K. E., Meadan, H., & Halle, J. W. (2017). Telepractice in speech–language therapy: The use of online technologies for parent training and coaching. Communication Disorders Quarterly, 38(4), 242–254. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525740116680424

Trivette, C. M., Dunst, C. J., Hamby, D. W., & O’Herin, C. E. (2009). Characteristics and consequences of adult learning methods and strategies. Research Brief, 3(1), 1–33.

Turgeon, S., Lanovaz, M. J., & Dufour, M. M. (2021). Effects of an interactive web training to support parents in reducing challenging behaviors in children with autism. Behavior Modification, 45(5), 769–796.

Vivanti, G., Trembath, D., & Dissanayake, C. (2014). Mechanisms of imitation impairment in autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 42(8), 1395–1405. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-014-9874-9

Wolf, M. M. (1978). Social validity: The case for subjective measurement or how applied behavior analysis is finding its heart. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 11(2), 203–214. https://doi.org/10.1901/jaba.1978.11-203

Zeng, S., Pereira, B., Larson, A., Corr, C. P., O’Grady, C., & Stone-MacDonald, A. (2020). Preschool suspension and expulsion for young children with disabilities. Exceptional Children, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1177/0014402920949832

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of iInterest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author acknowledges potential conflict of interest as intervention developers.

Research involving Human Participants

This research involved human participants

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants.

Funding

No funding was received for conducting this study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, J.D., Hacker, R.E., Meadan, H. et al. Challenging Behaviors Online Modules for Parents of Young Children with Disabilities: A Pilot Feasibility Study. Educ. Treat. Child. 45, 341–355 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43494-021-00067-x

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s43494-021-00067-x